Abstract

To what extent does government messaging influence the willingness of citizens to accept constitutional amendments that empower the executive during crisis? Leaders trying to increase their power often attempt to mobilize public opinion for emergency legislation by emphasizing institutional constraints and crisis severity. To test the extent to which the public is swayed by such rhetoric, a vignette survey experiment was conducted with a national sample of 2569 Japanese during the COVID-19 pandemic. The experiment asks respondents to consider the tradeoff between executive power and their own safety, in a realistic setting. We find robust null effects, suggesting that such messaging does little to sway respondents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research shows that members of the public are more accepting of executive authority and policies that violate individual rights during emergencies. One vein of scholarship identifies constitutional emergency power as a potential mechanism for democratic erosion (Agamben 2008; Ginsburg and Versteeg 2021; Lührmann and Rooney 2021). In line with this, those accused of democratic backsliding have often used rhetoric that emphasizes the acuteness of the emergency and how constitutional constraints on emergency power constrain the ability of the executive to manage the crisis at hand.

To what extent does government messaging influence the willingness of citizens to accept constitutional amendments? In this research, we show that while support for constitutional amendments that substantially increases emergency powers are high in our sample under a real crisis situation, support for such amendments do not appear to be affected by modes of rhetoric often used by those who attempt to increase emergency powers under emergencies–emphasis of the severity of the crisis and the degree to which existing legislation constrains government action to combat it.

We fielded a survey experiment in Japan with a national sample of 2569 respondents, recruited through Lucid Marketplace, an online survey platform that is becoming an increasingly popular tool for social scientists to conduct research (Coppock and McClellan 2019). While works such as Aronow et al. (2020) warn of issues with respondent quality for this platform, Jang et al. (2022) show that it provides high-quality respondents at least for Japan. To collect a reasonably representative sample of adults across Japan, we constructed our sample using demographic quotas with respect to respondents’ age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–74), sex (male, female), and region (Chugoku, Chubu, Hokkaido, Kinki, Kanto, Kyushu, Shikoku, Tohoku).Footnote 1 The appendix contains sample descriptives. Our survey experiment tests the causal effect of two emergency measures frames used by autocrats, (1) regarding the severity of a crisis and the (2) degree to which the government is constrained under existing laws, on the willingness of respondents to support constitutional amendments that expand emergency powers to differing degrees.

Japan is a good case to test the effect of rhetorical devices, or frames, often used to justify aggrandizement on the public’s willingness to expand emergency powers under a genuine emergency situation. Unlike in most other advanced industrialized democracies, constitutional amendments to expand such powers have been under discussion by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) for almost a decade (with much of the discussion revolving around the potential of these powers to result in rights violations), and the public sees COVID-19 as a genuine threat. Other countries have seen similar debates in recent years over security issues, as mentioned above, as well as over the COVID pandemic. However, with over two decades between now and the September 11 attacks in 2001, it is not quite possible to fully capture the atmosphere of the peak years of the War on Terror using a retroactive survey experiment. Thus, Japan is a case that provides an opportunity to study this general phenomenon, as both the threat of crisis and the prospect for constitutional change are most realistic in the eyes of the public (see “Case selection” section for further discussion of this issue). These issues could crop up in any country, but it just so happens that these are most applicable to the Japanese case at the time.

Furthermore, other than border controls and policies to increase hospital beds, Japanese COVID-19 restrictions took the form of largely voluntary recommendations, due to the lack of legal tools to enact coercive restrictions. The government was visibly powerless to enforce restrictions on business operations and public events, as detailed in the section on case selection. This perception of state weakness, combined with the uncertain and pressing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, allows us to test the determinants of support for expansive emergency powers in a context of a real crisis and a perceived lack of state authority.

We find that while a majority of our sample is willing to support constitutional amendments that result in substantial aggrandizement in the government’s right to act in violation of individual rights during the crisis, they are not affected by frames that exaggerate the severity of the crisis or emphasize the constitutional nature of the constraints faced by the government in combating it. Taken together, our results suggest some limits that governments face in mobilizing public opinion for removing constitutional constraints, and have implications for the growing literature on public health and politics as well as the broader literature on the determinants of human rights protections.

Theory: eroding rights through the state of exception

One of the main ways that governments can expand authority is by exploiting crises and claiming that only emergency actions can provide for public security. The expansion or exploitation of existing emergency laws is a common method governments use to erode constitutional constraints. In many of these cases, leaders exploit genuine crises that they emphasize or exaggerate–as Orban was accused of doing to justify passing emergency legislation that empowered him to rule by decree for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic (Beauchamp 2020)–or engineer them– as Hitler is alleged to have done with the Reichstag fire, leading to the use of emergency decrees and the passage of the enabling act to consolidate power and skirt the rights guaranteed by the Weimar Constitution through legal means (Schmidt 2009).

Legal scholars such as Ginsburg and Versteeg (2021) argue that emergency powers should be constrained by checks and balances to prevent abuse, and because executive action alone often does not suffice for effective crisis management. They argue in favor of employing checks and balances even during emergencies and against Schmittian theories of emergency powers that argue exceptional circumstances are necessarily outside the scope of a given constitutional order. Empirically, Fisunoğlu and Rooney (2021) show that while emergency powers can help governments extract resources to deal with national political emergencies, they may be inefficient for dealing with external crises.

The availability and use of constitutional emergency powers have also been associated with attempts by executives to concentrate power and undermine democracy. Rooney (2019) shows that democracies with more permissive constitutional emergency powers are more likely to initiate conflict. It shows that leaders in such countries are potentially using conflict escalation to increase their own authority via emergency powers. Furthermore, Lührmann and Rooney (2021) show that democracies are more likely to be eroded under states of emergency. Therefore, given the role that permissive emergency legislation plays in the usurpation of power by the executive, it is important to empirically demonstrate whether the public is swayed by rhetorical devices that are thought to enable leaders to enact more permissive emergency laws.

Three political actors can seriously constrain attempts to violate individual rights through emergency legislation. First, independent courts have been shown to constrain governments, in addition to constitutions that prohibit fundamental changes and empower courts to strike them down (Roznai 2017). Second, political elites, such as legislators from the incumbent and opposition parties, social elites such as established religious authorities, trade unions, the military, or even economic elites, can oppose such measures through direct and indirect means. In the case of Japan, bureaucratic organs such as the Cabinet Legislation Bureau have sweeping de facto oversight over proposed legislation. While they have not been as instrumental in the debates over emergency legislation, Abe had to use his appointment powers in an unprecedented manner to allow the cabinet to re-interpret Article 9 of the constitution and propose legislation that would legalize collective defense, instead of amending the constitution outright (Nakano 2021).

Finally, members of the public also have the ability to constrain backsliding. Voting backsliding candidates out of office notwithstanding, some constitutions require referendums (such as France or Japan, among others) for amendments (Lijphart 2012, 210–211), and even when this is not a requirement, many leaders choose to hold plebiscites for empowering legislation in order to emphasize public support and to undermine elite opposition (Albert 2017). Thus, voters stand in a potentially powerful position to constrain executive aggrandizement through emergency legislation.

However, during times of crisis, it can be difficult for the public to effectively prevent such amendments, even when they may reject such proposals under normal circumstances. We already know that members of the public support measures and ordinary legislation that empower executives under crisis. Under the COVID-19 Pandemic, extant studies have shown a high degree of support for constitutionally questionable measures such as suspension of the legislature and delayed elections (Lowande and Rogowski 2021), as well as restrictions on civil liberties (Chilton et al. 2020). In other cases, scholars have argued that rhetoric from political leaders in consolidated democracies drove public support for legislation that expanded executive power. For example, research shows that administration messaging from the Bush Administration was key for bolstering public support for the administration’s policies following the 9/11 attacks, pressuring Congress to quickly pass the PATRIOT Act of 2001 (Domke et al. 2006). Finally, survey research has shown that members of the public do indeed trade rights for security when faced with a rights-security tradeoff (Dietrich and Crabtree 2019). Can members of the public be swayed to support amendments that append sweeping constitutional emergency powers?

To deal with public reluctance, leaders might attempt to engage in “persuasion by framing” (Zaller and Feldman 1992, 610). We know that political elites can shape and focus public opinion on important issues (Achen and Bartels 2006; Zaller and Feldman 1992). They might wish to do so by exaggerating the dangers posed by an emergency. The historical examples referred to above provide clear case examples of when leaders have done this. Prior work also provides direct evidence that government rhetoric priming safety or security threats can induce the public to sacrifice their liberties (Crabtree et al. 2021; Dietrich and Crabtree 2019). This leads to our Safety Hypothesis.

Safety Hypothesis: The more dangerous a crisis is portrayed for public safety, the more the public will support emergency laws with greater abrogations of constitutional constraints.

In addition to exaggerating crises to make them seem more threatening, leaders may advocate for increasing the extent of emergency powers by portraying legal constraints as a hindrance to effective and needed measures to justify aggrandizement. Notably, Viktor Orban of Hungary has used such rhetoric, citing the “paralyzed nature of the then constitutional bodies” to justify the adoption of a new constitution in 2011 with expanded emergency powers (Kovács 2016). In the current COVID-19 pandemic, he has also used similar rhetoric in response to concerns voiced by European institutions regarding new emergency powers (Kovács 2020, 261). In the case of Poland, leaders in the ruling Law and Justice party have accused the independent judiciary of retaining Communists and preventing the “national majority” from implementing the “democratic will of the people” to justify an executive-led “purge” of the judiciary (Porter-Szucs 2018).

In the Japanese case, actors arguing in favor of amending the constitution, including members of the governing LDP, have also pointed to the potential inability of normal democratic institutions, such as courts and parliaments, to act swiftly enough during emergencies as a reason to justify proposed constitutional amendments that would increase emergency powers. For example, the LDP’s webpage “Four Items That We Want to Change” argues that while it is desirable to maintain parliamentary activities even during emergencies, when it is impossible to do so, constitutional emergency powers should be in place to give the cabinet temporary but overarching authority to deal swiftly with the problems at hand (Jiminto 2017).

This general logic leads us to our Constraint Hypothesis.

Constraint Hypothesis: If the public is exposed to rhetoric which claims that legal constraints on executive power impede the government ability’s to manage a crisis, they will be more likely to support emergency laws that expand executive power.

Finally, these treatments in combination may exert a greater effect than when they are used on their own; a perception of hindrance may bring about greater acquiescence when used in conjunction with dire portrayals of a crisis. This conditional expectation is outlined in our Conditional Safety and Constraint Hypothesis.

Conditional Safety and Constraint Hypothesis: The positive effect of rhetoric portraying a more dire crisis on support for more expansive emergency laws should increase with rhetoric that emphasizes the limitations of current legal constraints, and vice versa.

Before discussing how we test our hypotheses, we want to briefly discuss the stakes at play in either rejecting or failing to reject them. First, if we do not find support for the hypotheses above, then this would imply that the two types of frames we discuss do little to sway members of the public. This would also suggest that the public is swayed more by other factors, such as the objective conditions present in a society or more long-term processes that cannot perhaps be tested adequately using survey treatments.

If we find support for these hypotheses, it would show that the public can be driven to support potential abrogations of constitutional constraints by leaders invoking crisis and perhaps cannot be counted on to constrain expansions of executive power. Support for our hypotheses would both strengthen the importance of structural explanations (Svolik 2020) and the role of elite politics in maintaining constitutional constraints on the executive under emergencies. Furthermore, such a result would raise the importance of effectively delivering political messaging to the masses for those who may wish to oppose leaders who may be trying to enact emergency legislation to concentrate power, since this would show that such messaging has a substantive effect on support.

Case selection: Japan

The Japanese Constitution has been uniquely resistant to amendment. While this may at first show that the Japanese public is particularly obstinate on possible amendments, and is therefore an inappropriate sample to test our hypotheses with, research on Japanese public opinion in this area suggests this is not the case. The political left is opposed to revision, while this issue is less important for centrists (McElwain 2020). The lack of amendment so far is largely due to the constitution’s progressive content combined with a dearth of detail which allows particulars to be legislated outside of constitutional law, and coalitional concerns among conservative elites that keeps delaying amendment in favor of a focus on bread-and-butter issues (McElwain 2020; McElwain and Winkler 2015). Emergency legislation also remains an issue for which “public sympathy remains high" given people’s concern over disasters such as the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, despite its potential for abuse (McElwain 2018a, 302). Individuals without strong ideological convictions (the plurality in most surveys of the Japanese electorate) also do not maintain consistent positions on amendment over time (McElwain 2020, 36). We also see large majorities in favor of adding sweeping constitutional emergency powers to the Japanese constitution, showing that at least on this issue, our Japanese survey respondents are not especially resistant to amending the constitution.

While local and national governments worldwide have issued stay-at-home orders, many with binding penalties for noncompliance, the Japanese response at both national and local levels has been largely limited to voluntary requests, fiscal expenditures, and administrative instructions that are legally binding but without punishments for noncomplianceFootnote 2. The government declared an emergency on April 7th, based on Article 32, clause 1 of the “Novel Influenza Special Response Law" (Heisei 24/2012 Act Nr. 31) (Suzuki, 2020). This law does not empower the government to use coercive measures, other than limited provisions for temporary expropriation of private property for emergency medical use. Thus, many businesses such as restaurants and entertainment venues still operated, and closures were largely voluntary (Suzuki 2020). While most large events were canceled, these measures were still voluntary; on March 22nd, 2020, a wrestling event took place with around 6500 live attendees despite requests from local and national government officials to cancel the event (Imahashi 2020). Additionally, local governments were repeatedly requesting pachinko parlors (de facto gambling establishments) to shut down, but many refused to do so, and authorities were powerless to stop them, except by naming-and-shaming (which seemed to attract even more customers) (Kyodo News 2020). Thus, it can be seen that the Japanese “lockdown" was much less severe than in most other advanced industrialized democracies at the time the survey was conducted in October 2020. While Taiwan and South Korea have also refrained from enacting strict lockdowns, these governments introduced much more extensive testing and coercively enforced quarantines, tracing, and containment, and have also both moved faster and went farther in restricting potential contagion from overseas travel (Wingfield-Hayes 2020).

Japan’s Constitution

The LDP, which has been in power for most of the post-occupation period, has been calling for amendments to Japan’s 1946 constitution since its founding in 1955, though the issue was less emphasized after 1960 (McElwain and Winkler 2015, 267). Calls for amendment have become more acute since the early 2000s. Ex-premier Shinzo Abe was a strong proponent of revision (McElwain and Winkler 2015, 268). The incumbent PM during the survey experiment, Yoshihide Suga, had generally carried over the priorities of the previous government on major issues, albeit with a lesser emphasis on constitutional issues (Tolliver and Crabtree 2020). The two national leaders had explicitly called for additional clauses for states of emergency, an issue that became especially relevant following the Fukushima disaster and during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, among other items.

Importantly for the relevance of the Japanese case in analyzing the determinants of support for emergency laws that may undermine individual rights, critics of the incumbent LDP have long argued that the proposed amendments will undermine democracy and individual rights through failing to constrain the exercise of executive power and creating the potential for abuse Footnote 3. Thus, by the time this survey was fielded, the Japanese public had been frequently exposed to discourse that emphasizes the potential for expansive emergency powers to result in violations of human rights associated with the prewar period.

The current constitution contains limited emergency clauses in Article 54, which gives the cabinet limited authority to convoke an emergency session of the House of CouncillorsFootnote 4. Regarding the current crisis, government supporters claim that government action is constrained by constitutional law, preventing the government from using coercion to enforce quarantine measures. Figures from the ruling party explicitly argue that it is necessary to amend the constitution so that the state is able to deal with future emergencies (Johnston 2020).

Some opposition commentators argue that while it is true that the government does not have the legal basis to coercively enforce quarantine, the constraints arise from the specific statutory law that is in place right now to deal with the crisis, rather than constitutional law. The current basis of the emergency declaration was originally a 2012 statute that was passed to maintain public health during the last bird flu pandemic, which was recently modified to apply to COVID-19 (Repeta 2020). They point to the fact that the government was able to (and still do in some areas) maintain an exclusion zone following the Fukushima nuclear disaster as evidence that the government has constitutional authority to coerce private citizens in the name of public safety, if they passed statutes to this end and argue that this crisis does not demonstrate the need for constitutional emergency clauses (Johnston 2020; Repeta 2020).

In summary, the Japanese public viewed the coronavirus pandemic as a substantial public threat, and a large portion perceived the government’s responses as inadequate. Furthermore, the issue of potentially amending the constitution to add emergency clauses stood as a relevant and realistic prospect to the public, owing to the long-standing commitment to constitutional amendment of the government at the time and ongoing public debate over its necessity or lack thereof. Furthermore, much of the debate surrounding the introduction of constitutional emergency powers has been over its potential for enabling violations of individual constitutional rights by the government, resulting in a widespread awareness of the potential for abuse if the constitution were amended to provide strong emergency powers to the incumbent.

The concurrence of a lackluster response to the pandemic combined with long-standing calls by the Japanese government to add emergency clauses to the constitution from before the crisis enables us to test our hypotheses using a survey experiment in Japan, which we describe in the next section.

Survey experiment

After respondents were asked a set of socio-demographic and political attitudes questions – such as age, gender, income, support for the government, and party support – they were shown a vignette that provides a summary and short prognosis on the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. We randomly varied (a) narrative details on the severity of the pandemic and (b) rhetoric on whether the government is constrained by the constitution or not. Both of these factors had two levels each that were assigned randomly and independently of each other, with equal probability. Our outcome measures are the extent to which respondents approved of four different proposals for constitutional amendment, which varied in the degree of executive empowerment.Footnote 5

Treatments

To test the Safety Hypothesis, we assigned one of two different levels of crisis description to respondents. The first treatment provides an optimistic forecast, whereas the second provides a more pessimistic prognosis regarding the resurgence of COVID. These treatments were written to reflect statements that people would be likely to find realistic, given the uncertain media coverage at the time. There is a tradeoff between realistic statements (i.e., ecologically valid treatments) and the strength of treatment. A potential shortcoming of this experiment is that the null result is due to a ‘weak’ treatment. We believe that this result is still interpretable due to the realistic nature of the treatment–it is something that people are likely to hear, even from non-partisans sources, and thus is able to isolate the types of innocuous-sounding messages that are often used to justify less innocuous ends. In contrast, a stronger, or extreme treatment (i.e., you will die because we are unable to enforce quarantine due to constitutional constraints), is likely to be unrealistic, which may make it less applicable to examples of gradual of executive empowerment that over time concentrates power in the executive beyond what can be reasonably maintained in a functioning democracy.

Safety treatments

-

1.

The Coronavirus crisis has resulted in many infections and deaths. It is extremely disruptive of daily life in Japan, and is responsible for a deepening depression. However, Japan has avoided the calamitous outbreaks that were seen in the US and Europe, and experts surmise that the crisis will naturally wind down by the end of this year, and be gone for good with the introduction of vaccines.

-

2.

The Coronavirus crisis has resulted in many infections and deaths. It is extremely disruptive of daily life in Japan, and is responsible for a deepening depression. However, Japan has avoided the calamitous outbreaks that were seen in the US and Europe, though experts warn that more severe outbreaks could recur in the fall and winter, before vaccines are ready for general use.

Given that the survey was conducted following the second major spike in COVID cases in Japan in the summer of 2020, but prior to the third spike in new COVID cases that began in November 2020, both scenarios would have seemed plausible to survey-takers, and people would have heard conflicting prognoses on the matter Footnote 6.

To test the Constraint Hypothesis, the survey varied the degree to which government action was seen as being constrained by the constitution. While this treatment may initially appear to be of little consequence, the issue of constitutional amendment is rather divisive in Japan (McElwain 2018b), with both left- and right-wing parts of the electorate tending to take strong stances on it, while centrists tend to find it less salient (McElwain 2020). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, both the government and opposition took stances on the specific issue of whether it was necessary or not to amend the constitution to empower the executive to deal with such crises, and engaged in a public debate (Aizawa 2020). Therefore, it is likely that respondents were aware of such issues and took them into account when responding to the amendment proposals. This treatment is meant to convey the types of speech that leaders who are advocating for constitutional reforms tend to use in justifying their stance.

Constraint treatments

-

1.

Quarantine measures are key for containing such epidemics and keeping citizens safe. In dealing with this crisis, the government has declared a state of emergency, but has not implemented the types of mandatory stay-at-home and business shutdown measures that have been commonly deployed in other countries.

-

2.

Quarantine measures are key for containing such epidemics and keeping citizens safe. In dealing with this crisis, the government has declared a state of emergency, but has not been able to enforce the types of mandatory stay-at-home and business shutdown measures that have been commonly deployed in other countries, due to constitutional constraints.

As a reminder, we crossed the two different factors – safety and constraint – so respondents receive one of four different treatment combinations (S1 + C1, S1 + C2, S2 + C1, S2 + C2).

Outcome measures

After reading the vignette, respondents were asked to answer whether they would vote for a proposed constitutional amendment that would add emergency powers to the constitution. They were asked this question for four separate amendments with different levels of executive empowerment in the amendment proposals, with executive empowerment increasing from A1 to A4 in a level that was only slightly different from the status quo (A1) to a level at which the prime minister could unilaterally initiate perpetual rule by decree (A4). The order of these questions was randomized to reduce the possibility of order effects. While the outcome measures may appear rather complex, Japanese media often present quite subtle and detailed comparisons of various policy proposals and the differences across political parties in issues across many dimensions. For example, both the public television broadcaster and major newspaper outlets often provide issue-by-issue comparisons of party manifestos and policy proposals in regular news coverage, making subtle distinctions between the positions of the parties. In other words, we have decided to present ecologically valid treatments, despite their complexity, to maximize the likelihood that our findings travel to the real world.

As countries face unforeseeable emergency situations outside the scope of normal politics, such as wars, civil strife, natural disasters, and pandemics, many constitutions around the world contain emergency clauses to empower the head of government to carry the country through. In these circumstances, ordinary institutions such as parliaments and courts may not be able to act swiftly enough, or even convene at all.

The following is a table that summarizes a proposal for additions to the current constitution to bolster our nation’s ability to effectively overcome unanticipated crises. If this law passes through both houses of the Diet and is put to referendum according to Article 96 of the current constitution, how would you vote? Please read carefully and stop to think about the implications of these measures.

Table 1 presents all four amendment proposals. Each time the question is asked, only one column out of A1 to A4 will be shown. A1 is similar to an earlier LDP proposal but with stronger limits on the executive, and A2 largely summarizes the LDP proposal. A3 adds further powers, and A4 outlines a situation where the Prime Minister is able to unilaterally assume near-dictatorial powers. Each proposal empowers the executive to a differing degree (with A4 providing the greatest extent of powers to the executive and A1 giving the least amount of power), allowing us to construct an ordinal measure of the extent to which respondents support executive empowerment (relative to the status quo). We also looked at an alternative outcome, that is, “approve any amendment at all", to see the effect of our treatment on the willingness to approve any of the amendments at all, alleviating the concern that the result is simply driven by the inability of the respondent to discern between the amendment proposals.

Results

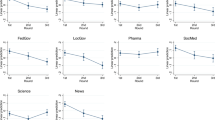

Before formally testing our hypotheses, we visually present our outcome measures. Figure 1 shows a summary of the responses to each of the amendment proposals shown in Table 1. Amendment 1 is the least drastic change, which only allows emergencies to be declared with Diet approval, and whereas binding decrees can be issued, they are still subject to other legal restrictions and must be approved ex-post. In this proposal, the Prime Minister is fairly heavily constrained in declaring the emergency, as well as implementing policy during, and requiring ex-post approvals after the emergency. Amendment 2, which has the highest approval overall, largely follows the 2012 LDP proposal. This proposal allows the Prime Minister to violate existing laws during emergencies and prevents the Diet from unilaterally rescinding the State of Emergency. Furthermore, this empowers the government to suspend elections and term limits. The third amendment removes the need for the Diet to approve of the emergency declaration, and Amendment 4 allows emergency decrees to stay after the Emergency without parliamentary approval and allows the Prime Minister to extend Emergencies without parliamentary approval. These overall high levels of approval may induce some ceiling effects, limiting our ability to detect treatment effects, but a substantial proportion of respondents do not approve of any particular amendment.

Amendment A4, with the highest degree of executive empowerment, has the least support, followed by A1, which provides little to no change from the status quo. The highest approvals are for A2 and A3, which enable moderate levels of executive empowerment. The “Disapprove All" measure shows the proportion of respondents who opposed all amendments.

Figures 2 and 3 show the difference in means across the four outcome variables for the two treatments. The “control" group shows the distribution for all those who were shown the pessimistic vignette for Fig. 2 and those who were not shown the text that mentions constitutional constraints in Fig. 3. Already, one can see that the differences across the treatments are minute and that the estimates are relatively precise.Footnote 7

For our main analyses, we test our hypotheses by fitting an ordinary least squares (OLS) model as a linear probability model. This is done for the ease of interpretation of the coefficients. However, similar results hold when using logistic regression, as the results in the appendix show. The main OLS model is specified in the following manner:

Where yji is a binary indicator for whether respondents voted for the j constitutional amendment for the ith respondent, safetyi is a dummy variable which is equal to one when S1 of the safety treatment is shown, and constrainti is likewise a dummy variable which is equal to one when the C1 of the constraint treatment is shown, which does not mention constitution constraints, and Xi is a vector of all the other covariates.

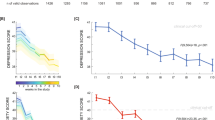

Figure 4 displays the results. Plotted points denote estimated coefficients, and the whiskers show 90 and 95 percent confidence intervals. As the figure shows, all of the estimated coefficients are not statistically significant at conventional levels, with the strongest apparent effect for support on the least empowering amendment.

Not only are these effects insignificant, they are also small in magnitude – taking the lowest and highest extremes of the 95 percent confidence intervals in the coefficient plot for the interaction model in Fig. 4, one either sees an approximately six percent increase in approval for the least radical amendment proposal when mentioning constitutional constraints. We likewise see a maximum seven percent change in approval for the least radical proposal when providing a more optimistic scenario in the vignette. Similar null results hold when estimating the same model without the interaction, as shown in the appendix.

One concern for our inference is that the survey experiment was conducted at a point in time when public approval for both the government and the coronavirus policy were relatively high, as indicated in Fig. 5. This may have increased the number of respondents approving of increases in executive power, and also made them more impervious to manipulations regarding the severity of the pandemic and the constitutional limitations on the government’s ability to act. However, these points should be considered in light of the inferences possible in previous or subsequent periods – at this point, there was no clear timeline for the deployment of the vaccine, and there were also fears of subsequent waves. People had also clearly seen the inability of the government to implement effective measures earlier in the year.

Discussion

In the appendix, we also look at treatment effect heterogeneity and find null results for most subsets of our respondents, except for Komeito supporters (N = 112). They were significantly less likely to support the two least empowering amendments when shown the vignette where the constitutional constraints were mentioned as hindrances. Komeito has been a long-term coalition partner of the conservative LDP and supports amending the constitution for issues such as writing additional rights, but is opposed to expanding executive power and war-making capabilities (Komeito 2013). So far, they have prevented the LDP from moving forward with constitutional amendment procedures and this issue has been a point of contention in the coalition which may explain why they reacted so strongly to the treatment, though this does not explain why we also find null effects for the left-wing opposition parties who are the most vocal opponents of constitutional amendment (Liff and Maeda 2019). It may be that supporters of these parties are more set in their ways one way or another, whereas the conditional stance of Komeito makes their supporters more susceptible to treatments. In general, we think that these and other conditional results should be treated with some skepticism, given that they are the results of exploratory analysis and also suffer from potential multiple comparison problems.

Despite mixed support in earlier polls and the lack of the effect proposed, these results show that at least during the height of COVID-19, the government may have been able to garner decent mass support for amending the constitution to clarify emergency laws. However, had the government done so, it would have been likely to generate a backlash from elites such as opposition parties, civil society groups, and mainstream media organs, if the government could not effectively control the narrative. Substantively, those who wish to amend the constitution may find it easier to do so on issues other than the controversial peace clause in Article 9.

Conclusion

The results of our survey experiment provide both positive and negative conclusions for the robustness of constitutional checks and balances in the face of emergency situations. On the one hand, they demonstrate that the electorate, at least in this case, is not subject to much manipulation by rhetorical devices commonly attributed to those who seek to undercut constitutional rights protections, such as exaggerating the limits faced by the government or the severity of a given crisis. Therefore, other factors are likely to be the drivers of changes in support for constitutional emergency powers.

Simultaneously, our findings also show that the majority of the respondents are willing to vote for even quite drastic constitutional amendments to contravene constitutional rights guarantees. This follows previous research conducted over the course of this pandemic that demonstrates public willingness to forgo their liberties, and that emphasizing efficacy seems to matter over constitutionality in finding support for restrictive quarantine policies (Chilton et al. 2020). This result also follows a trend seen in other advanced industrialized democracies over crisis management that has seen a decrease in satisfaction with democracy and trust in parliaments among European electorates through the Eurozone crisis (Armingeon and Guthmann 2014).

Therefore, the commonly criticized modes of speech, or frames, used by leaders trying to undercut constitutional human rights guarantees may be epiphenomenal to the demonstrated abilities of incumbent regimes to face and solve crises. However, a full understanding of the relationships between crisis and human rights will require further research on the relationships between perceived competence during times of great duress. Additionally, given that majorities among the respondents were willing to approve a relatively wide range of proposals in this case, it is up to elite institutions, such as interest groups, parties, legislatures, and courts, to prevent leaders from placing such laws on the public agenda in the first place.

There are several limitations to our results. As null effects, they may simply be the result of weak treatment, ceiling effects, and the fact that the survey was conducted around the peak of cabinet and government COVID-19 policy support, which may explain both the high absolute magnitude of support for wide-reaching emergency powers and the lack of treatment effects.

However, we believe these issues must be considered in the light of the degree of realism that our survey experiment provides, which is difficult to obtain outside of this context, in particular the Japanese political context surrounding emergency legislation. Uniquely among advanced industrialized democracies, constitutional emergency powers are not a “settled" issue in Japan, with an ongoing debate surrounding the issue, making the amendment proposals a realistic proposition for respondents. Furthermore, the survey period was at a relative lull between the second and third waves of COVID-19 in Japan. During this period, Japanese people saw news reporting of extensive outbreaks abroad. Concurrently, the timeline for the development and deployment of new, effective, and safe vaccines was also uncertain. These points help make our alternative vignettes for the Safety Hypothesis appear more realistic– the situation was not so dire as to make the “optimistic" vignette sound unreasonably drastic, and the uncertainty surrounding the vaccine and the situation abroad also made the “pessimistic" vignette plausible.

Our results raise several further avenues of research. Given the limitations of this study, further research is warranted to investigate whether the public may be more amenable to manipulation by framing under different circumstances. Finally, one wonders how different types of crises may or may not be amenable to rhetorical framing– it may be that what applies to pestilence does not apply to foreign attacks or threats of internal subversion, given the tendency of such incidents to generate great disagreement over the nature of the threat, while having a more immediate urgency. In such cases where human agency plays a greater role in causing the threat, there is also a general concern that these events were planned as false flags or allowed to happen by the leader. Such concerns among members of the public provide another avenue for manipulating them to oppose executive empowerment, requiring further research.

Data availability

All data and computer code necessary to replicate the results in this analysis will be made publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/H3Q4Y. R 4.0.3 was the statistical package used in this study.

Notes

To create these quotas, we used respondent answers to standard qualifications questions asked by Lucid. Respondents completed these questions before being directed to our Qualtrics survey.

Yan et al. (2020) argues that this was due to Japan’s devolution of powers to local governments combined with a “tight" culture that results in greater compliance to voluntary requests. Lipscy (2023) argues that the relatively lax restrictions were due to the incumbent’s emphasis on the economy, policy paralysis from intraparty challenges induced by the pandemic, and devolution allowing regional governors to challenge central policies, along with a failure to manage the media narrative by the Abe government.

This can be seen in even English-language publications (Goodman 2017; Hiroshi 2016), and often invokes the use of emergency powers under the Weimar Constitution as an example of excess emergency powers leading to authoritarianism. Similarly, in a newspaper article reports on an anti-revision rally in May 2020 where Prof. Yamaguchi Jiro of Hosei University proclaimed that “Giving the incompetent Abe government emergency powers is nothing but a destruction of constitutionalism and democracy" (The Sankei News 2020).

For more information about Article 54 and proposed additions suggested by LDP deputies, see Appendix 1.

We presented these proposals in randomized order to reduce the possibility of any order effects.

For example, some Japanese epidemiologists at the time claimed that Japanese people already gained herd immunity against COVID-19, hence the low rates of infection and death at the time. These arguments were also reported in news media (Mainichi Daily News 2020c). At the same time, the spread of the pandemic in Europe and the Americas and concurrent rises in fatalities were widely reported in the Japanese media, as were claims, made by other scholars as well as the WHO, that natural herd immunity could not be relied upon to guard against the pandemic, and would require widespread vaccinations (Mainichi Daily News 2020d). Reporting on vaccine tests and prognosis of widespread availability was also mixed, as testing showed that some potential vaccines were ineffective or unsafe (Mainichi Daily News 2020a, b).

One concern might be that respondents were asked to evaluate four potential candidates of constitutional amendments instead of just one. The issue here could be that this created some sort of ‘anchoring effect’ and that subsequent answers may be affected by the answer to a previous question on relative terms. The result of this could have been that anchoring effects possibly distorted the results. To investigate this, we examine respondent approval for only the First Amendment shown. The results of these analyses are substantively similar. Furthermore, this also partially mitigates the concern that results may have been driven by respondents’ attention potentially faltering after the first amendment proposal.

References

Achen CH, Bartels LM (2006) It feels like we’re thinking: The rationalizing voter and electoral democracy. In: Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, vol 30

Agamben G (2008) State of exception. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA

Aizawa Y (2020) Coronavirus and the debate over constitutional change. NHK WORLD

Albert R (2017) Discretionary Referenda in Constitutional Amendment. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3025772, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Armingeon K, Guthmann K (2014) Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. Eur J Political Res 53(3):423–442

Aronow PM, Kalla J, Orr L, Ternovski J (2020) Evidence of rising rates of inattentiveness on lucid in 2020. SocArXiv, 49, 59–63

Beauchamp Z (2020) Hungary’s “Coronavirus Coup,” Explained. Vox. Library Catalog: www.vox.com

Chilton AS, Cope KL, Crabtree C, Versteeg M (2020) Support for restricting liberty for safety: evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic from the United States, Japan, and Israel. Japan, and Israel SSRN Electronic J 10 (2020). (Accessed May 2, 2020)

Coppock A, McClellan OA (2019) Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Res Politics 6(1):2053168018822174

Crabtree C, Koo J-W, Murdie A, Tsutsui K (2021) Why the public and elites support human rights

Dietrich N, Crabtree C (2019) Domestic demand for human rights: free speech and the freedom-security trade-off. Int Stud Q 63(2):346–353

Domke D, Graham ES, Coe K, Lockett John S, Coopman T (2006) Going public as political strategy: the bush administration, an echoing press, and passage of the patriot act. Political Commun 23(3):291–312

Fisunoğlu A, Rooney B (2021) Shock the system: emergency powers and political capacity. Governance 34(2):457–474

Ginsburg T, Versteeg M (2021) The bound executive: Emergency powers during the pandemic. Int J Const Law 19(5):1498–1535

Goodman C (2017) The threat to Japanese democracy: The LDP plan for constitutional revision to introduce emergency powers. Asia–Pac J 15(10)

Hiroshi I (2016) Hitler’s dismantling of the constitution and the current path of Japan’s abe administration: what lessons can we draw from history? Asia–Pac J 14(16)

Imahashi R (2020) K-1 organizer harshly criticized over Japan match amid virus. Nikkei Asian Review

Jang J, Crabtree C, Ono Y (2022) Assessing survey response quality in Japan: evidence from over 50 surveys. Paper presented at the Japan Society for Quantitative Political Science, Tokyo, Japan

Jiminto (2017) Yottsu no “kaetaikoto” jiminto no teian [four things we want to change - the liberal democratic party’s proposal] https://www.jimin.jp/kenpou/proposal/

Johnston E (2020) Necessary or not? The LDP’s proposed emergency powers clause for the Constitution. The Japan Times. www.japantimes.co.jp

Komeito N (2013) Komeito no kenpo kaisei [the komeito’s constitutional revision proposal] https://www.komei.or.jp/campaign/sanin2013/ig/kp.html

Kovács K (2020) Democracy in lockdown. Soc Res Int Q 87(2):257–264

Kovács K (2016) Hungary’s struggle: in a permanent state of exception. Verfblog

Kyodo News (2020). Not All Pachinko Parlors in Tokyo Shut, 600 Still Investigated. Kyodo News. Library Catalog: english.kyodonews.net

Liff AP, Maeda K (2019) Electoral incentives, policy compromise, and coalition durability: Japan’s LDP–Komeito government in a mixed electoral system. Jpn J Political Sci 20(1):53–73

Lijphart A (2012) Patterns of democracy: government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2nd edn

Lipscy PY (2023) Japan’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In: Japan decides 2021. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp 239–254

Lowande K, Rogowski JC (2021) Executive power in crisis. Am Polit Sci Rev 115(4):1406–1423

Lührmann A, Rooney B (2021) Autocratization by decree: states of emergency and democratic decline. Comp Politics 53(4):617–649

Mainichi Daily News (2020a) 2nd COVID-19 vaccine trial paused over unexplained illness. Mainichi Daily News

Mainichi Daily News (2020b) Experts call Trump’s rosy virus message misguided. Mainichi Daily News

Mainichi Daily News (2020c) Experts suspect cross immunity explains Japan’s low coronavirus death rate. Mainichi Daily News

Mainichi Daily News (2020d) Who warns against pursuing herd immunity to stop coronavirus. Mainichi Daily News

McElwain KM, Winkler CG (2015) What’s unique about the Japanese Constitution? A comparative and historical analysis. J Jpn Stud 41(2):249–280

McElwain KM (2018a) Constitutional revision in the 2017 election. In: Pekkanen RJ, Reed SR, Scheiner E, Smith DM (eds) Japan decides 2017: the Japanese general election. Springer International Publishing, pp 297–312

McElwain KM (2018b) Constitutional revision in the 2017 election. In: Japan Decides 2017. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, pp 297–312

McElwain KM (2020) When candidates are more polarised than voters: constitutional revision in Japan. Eur Polit Sci 19(4):528–539

Nakano K (2021) The politics of unconstitutional constitutional amendments in Japan: the case of the pacifist article 9. In: The law and politics of unconstitutional constitutional amendments in Asia. Routledge, pp 23–45

Porter-Szucs B (2018) Poland’s judicial purge another step toward authoritarian democracy. The Conversation

Repeta L (2020) The coronavirus and Japan’s Constitution. The Japan Times

Rooney B (2019) Emergency powers in democracies and international conflict. J Confl Resolut 63(3):644–671

Roznai Y (2017) Unconstitutional constitutional amendments: the limits of amendment powers. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom

Schmidt I (2009) Reichstag Fire of 1933. In: The international encyclopedia of revolution and protest, 1st edn. Wiley-Blackwell, pp 1–2. _eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1250

Suzuki N (2020) Emergency declaration tests conformity as coronavirus strains health care. Kyodo News. Library Catalog: english.kyodonews.net

Svolik MW (2020) When Polarization Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents. Q J Political Sci 15(1):3–31. Publisher: Now Publishers, Inc

The Sankei News (2020) Gokenha ga kokkaimae de shukai kinkyujitaijoukou heno hihan aitsugu [pro-constitutionalists rally in front of diet – follows with criticisms of emergency laws]. The Sankei News

Tolliver S, Crabtree C (2020) Five ways in which Japan’s new Prime Minister Suga is different from Abe. TheHill

Wingfield-Hayes R (2020) Why is There so Little Coronavirus Testing in Japan? BBC News

Yan B, Zhang X, Wu L, Zhu H, Chen B (2020) Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. Am Rev public Adm 50(6-7):762–769

Zaller J, Feldman S (1992) A simple theory of the survey response: answering questions versus revealing preferences. Am J Polit Sci 36(3):579–616

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Charles Crabtree was the principal investigator and fielded the survey. Harunobu Saijo conducted the literature review, analysis and conducted all translations between English and Japanese. Both parties took part in brainstorming for the research project, as well as in writing and editing the survey/manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The survey experiment described in this paper received IRB approval (Study #STUDY00032182) from the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The approval was granted on October 7, 2021, following an application on October 3 for the scope of conducting this survey.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. We obtained written consent from respondents prior to them taking the survey. The dates changed depending on when respondents completed the survey. The scope of the consent covers participation and data use. The study does not involve vulnerable individuals. • Principal Investigator: Charles Crabtree • Address: Charles Crabtree, Department of Government, 211 Silsby Hall, 3 Tuck Mall, Hanover, NH 03755. Telephone Number: +1 (720) 236-0778. • I am asking you to be in a research study. This form gives you information about the research. Whether or not you take part is up to you. You can choose not to take part. You can agree to take part and later change your mind. Your decision will not be held against you. Please ask questions about anything that is unclear to you and take your time to make your choice. • Why is this research being done? I am asking you to be in this research because I want to study individual behavior. This research is being done to find out how people respond to different survey questions. • What will happen in this research study? Procedures 1. Click ‘yes’ at the bottom of this consent form if you agree to participate in this study. Then, click the arrow button on the bottom-right corner of the page to begin. 2. Answer some questions and potentially complete some tasks. You might be contacted to participate in future research projects. • What are the risks and possible discomforts from being in this research study? There is a risk of loss of confidentiality if your information or your identity is obtained by someone other than the investigators, but precautions will be taken to prevent this from happening. The confidentiality of your electronic data created by you or by the researchers will be maintained to the degree permitted by the technology used. Absolute confidentiality cannot be guaranteed. You may feel emotionally uneasy when asked to make judgments based on the information provided in the study. • What are the possible benefits from being in this research study? You will help advance our understanding of individual behavior among people in your country. • What other options are available instead of being in this research study? You may decide not to participate in this research. • How long will you take part in this research study? I estimate that you will spend 15-20 minutes participating in this particular study. • How will your privacy and confidentiality be protected if you decide to take part in this research study? Efforts will be made to limit the use and sharing of your personal research information to people who have a need to review this information. Your research records will be kept on a Dartmouth office device, a university-approved and secure device. In the event of any publication or presentation resulting from the research, no personally identifiable information will be shared. I will do my best to keep your participation in this research study confidential to the extent permitted by law. • Will you be paid to take part in this research study? Participants will receive compensation from the survey firm for their participation. • What are your risks if you take part in this research study? Taking part in this research study is voluntary. You do not have to be in this research. • If you choose to be in this research, you have the right to stop at any time. • If you decide not to be in this research or if you decide to stop at a later date, there will be no penalty or loss of benefits to which you are entitled. • If you have questions or concerns about this research study, whom should you call? Please call the head of the research study (principal investigator), Charles Crabtree at (crabtree@dartmouth.edu) if you have questions, complaints, or concerns about the research, or believe you may have been harmed by being in the research study. • Informed consent to take part in research: Your participation implies your voluntary consent to participate in the research. Please keep or print a copy of this form for your records.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saijo, H., Crabtree, C. Mass receptiveness to unconstrained emergency legislation during crisis: survey experiment in pandemic-era Japan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04703-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04703-4