Abstract

Tourism plays a vital role in driving global economies by facilitating cultural exchange, creating job opportunities, and advancing sustainable development, making it a fundamental pillar of international growth and community strength. While many studies have examined the connection between tourism and economic growth, previous research has often neglected the potential reciprocal effects of economic growth on tourism. This study utilizes the IV-GMM and Pooled Mean Group (PMG) models to analyze the intricate relationship between tourism and economic growth across 35 Asian countries from 2004 to 2020. In addition to exploring the linear relationship, we investigate the asymmetric dynamics and the mediating connections. Furthermore, this study assesses the moderate impact of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our key findings reveal that economic growth substantially boosts tourism demand. To verify robustness, we use alternative dependent and independent variables. The results show that economic growth has an asymmetric relationship with tourism, especially across countries with low, medium, and high levels of tourism demand. Moreover, economic growth drives tourism demand by influencing national income and exports. Additionally, the SDGs not only exhibit a direct positive impact on tourism demand but also serve as a moderating factor in the relationship between economic growth and tourism. Governments should align tourism strategies with economic growth policies by investing in infrastructure and leveraging exports to boost tourism demand. Integrating SDGs into these strategies can ensure long-term, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Economic growth plays a crucial role in driving various sectors, with its impact on tourism being especially notable. As an industry closely linked to economic trends, tourism both gains from and contributes to broader economic development. The nexus between economic growth and tourism has emerged as a vital research focus, especially within the context of Asian countries. These rapidly developing nations provide a distinctive setting to examine the impact of economic factors on tourism growth. Economic advancement improves infrastructure, services, and international attractiveness, thereby driving greater tourism demand (Ravinthirakumaran et al., 2020; Lee & Chang, 2008). Additionally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a framework for ensuring that growth remains sustainable and inclusive, fostering tourism that supports economic development while preserving environmental and social resources (Song, Dwyer, Li, & Cao, 2012; Tang & Tan, 2015). This study seeks to examine the influence of economic growth on tourism in Asian countries, with a focus on the SDGs as a moderating factor and the mediating roles of exports and national income.

Economic growth impacts tourism demand through multiple channels. An increase in national income generally raises disposable income, allowing more individuals to travel for both leisure and business (Seetanah, 2011; Crouch, 2011). Furthermore, economic growth frequently enhances infrastructure, including airports and roads, which improves accessibility and boosts the appeal of destinations (Blake et al., 2006). The SDGs act as a moderating factor by ensuring that tourism growth is both sustainable and inclusive, encouraging environmentally friendly practices and fair economic benefits (Gössling, Hall, & Weaver, 2009). Additionally, the impacts of exports and national income serve as mediators; higher exports can improve a country’s global reputation and appeal, while increased national income can stimulate domestic tourism (Eugenio-Martin, Martín Morales, & Scarpa, 2004; Lee, 2012). Despite favorable trends, several challenges persist. The swift expansion of tourism in Asia has raised concerns about sustainability and fair development (Gössling & Peeters, 2015). Over-tourism in well-known destinations such as Bali and Bangkok have put pressure on local resources and infrastructure, leading to environmental damage and social problems (Sukserm & Ussahawanitchakit, 2017; Dwyer et al., 2000). Additionally, economic disparities among countries and within regions pose significant challenges to inclusive growth (Hall, 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the tourism sector’s vulnerability to global shocks, highlighting the need for resilient and sustainable tourism models (Hall, Scott, & Gössling, 2020). Therefore, the problem is the unsustainable growth of tourism in Asia, which has led to environmental degradation, social issues, and economic disparities. This problem is further exacerbated by the sector’s vulnerability to global shocks, as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the urgent need for more resilient and equitable tourism models.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are crucial in addressing the challenges tied to the rapid expansion of tourism, especially in Asia. They offer a comprehensive framework that promotes sustainable practices aimed at protecting the environment, advancing social equity, and ensuring economic inclusivity. In the context of economic growth and tourism, the SDGs shape this relationship by fostering practices that balance economic gains with the preservation of natural and cultural resources. For instance, over-tourism in places like Bali and Bangkok has caused environmental harm and social problems, which the SDGs seek to address through objectives focused on sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11), responsible consumption and production (Goal 12), and climate action (Goal 13) (Gössling & Peeters, 2015; Sukserm & Ussahawanitchakit, 2017).

Additionally, the SDGs emphasize the need to reduce economic inequalities (Goal 10), which is especially important given the challenges of achieving inclusive growth within and between countries in Asia. By advocating for more equitable and sustainable tourism models, the SDGs ensure that tourism-driven economic growth benefits a wider population while protecting the environment, thus supporting the long-term resilience of the tourism sector (Hall, 2010; Hall, Scott, & Gössling, 2020).

Detailed studies can offer valuable insights into how these unique contexts shape the relationship between tourism and economic growth, leading to more customized and effective policy recommendations (Tang & Tan, 2015). As such, research granularity is crucial for tackling the complex and multifaceted nature of tourism development in Asia and for enhancing our understanding of the connection between economic growth, sustainability, and tourism. Lastly, there is a gap in understanding the long-term impacts of global disruptions, like the COVID-19 pandemic, on the tourism sector, particularly how these events might influence the future trajectory of tourism development and its relationship with economic growth (Hall, Scott, & Gössling, 2020). Therefore, the three research questions (RQ) are addressed. First, it seeks to understand how economic growth (EG) impacts tourism demand (TOUR) in Asian countries. Second, it examines the role of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in moderating the relationship between economic growth and tourism. Finally, the study investigates how factors such as exports and national income mediate the effect of economic growth on tourism in these countries.

After a thorough review of the existing literature, this study proposes that economic growth has a significant impact on tourism. To provide a novel perspective, the research utilizes a three-stage framework. The first stage investigates the effect of economic growth (EG) and other control variables (SDG, REC, FIN, and EE) on tourism (TOUR) across 35 Asian countries from 2004 to 2020. In the second phase, the study introduces the SDG as a moderating variable in the relationship between EG and TOUR, marking its first use in this context. The third phase examines the mediating effects of exports and national income. This multi-phase approach aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between EG and TOUR in the Asian context over the specified period.

To illustrate the direct, moderating, and mediating effects (as shown in Fig. 1), the study uses IV-GMM (Instrumental Variables Generalized Method of Moments) regression analysis as the primary model. This choice of advanced econometric methods is intentional, selected to address potential issues such as reverse causality and endogeneity in the dataset, ensuring robust and reliable results. Additionally, panel quantile regression is employed to examine the nonlinear relationships between variables. By applying these sophisticated techniques, the study improves the accuracy and dependability of its findings, providing a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the relationship between economic growth and tourism across the 35 Asian countries during the study period.

Literature review

Many studies have individually examined the impact of tourism and other factors on economic growth, as well as the reciprocal effects of economic growth on various variables (Seetanah, 2011; Crouch, 2011; Işık et al., 2024a; 2024c; 2024d; 2024e; 2024f; 2024g; Gazi et al., 2024; Islam et al., 2023; Islam et al., 2024;). Nevertheless, there is a significant gap in the literature regarding a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between economic growth and tourism demand, especially when considering the role of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as moderating factors and exploring mediating effects. So, our goal is to fill this gap by examining the direct, moderating, and mediating effects of economic growth on tourism, incorporating SDGs as moderating variables and export and national income as mediating variables. This approach is innovative in the academic field. By concentrating on Asian countries, the study aims to thoroughly explore the intricate interactions among these factors, offering valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and stakeholders involved in sustainable development efforts.

Empirical studies

Economic growth has a substantial impact on tourism demand, primarily through increased national income and enhanced infrastructure. Higher income levels typically result in greater disposable income, enabling more individuals to travel for leisure or business (Seetanah, 2011; Crouch, 2011). This connection is particularly noticeable in many Asian nations, where rapid economic expansion has been accompanied by a rise in both domestic and international tourism (Ravinthirakumaran et al., 2020). For instance, China’s economic growth has fueled the expansion of its middle class, driving a significant increase in outbound tourism (Li et al., 2005). Similarly, India’s growing economy has led to a notable rise in both domestic and international travel (Suresh & Senthilnathan, 2014). Economic growth also allows governments to invest in infrastructure upgrades, such as improved roads, airports, and public transportation, which enhance destination accessibility and appeal (Blake, Sinclair, & Campos Soria, 2006; Tang & Tan, 2015). These infrastructure enhancements not only elevate travel experience but also stimulate the expansion of tourism-related businesses, further driving economic development (Lee & Chang, 2008).

The impact of economic growth on tourism demand is influenced by factors such as export effects and national income. Increased exports can elevate a country’s global image and appeal, attracting more international tourists (Eugenio-Martin et al., 2004). For example, South Korea’s export-driven promotion of its pop culture has significantly boosted tourism to the country (Kim et al., 2008). Higher national income also supports domestic tourism by providing individuals with greater financial means for travel (Tang & Tan, 2015). However, the relationship between economic growth and tourism demand is multifaceted, with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) playing a moderating role. SDGs ensure that tourism development is sustainable, fostering practices that protect the environment and support local communities (Gössling et al., 2009). Sustainable tourism practices are becoming increasingly vital as destinations aim to balance economic gains with environmental and social responsibilities (Hall, 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic has further emphasized the necessity for resilient tourism models capable of enduring global economic disruptions, reinforcing the importance of sustainability (Hall et al., 2020). While economic growth and tourism demand are closely linked—driven by higher national income and improved infrastructure—challenges such as uneven development and the sustainability of tourism growth in fast-growing economies remain significant concerns.

Numerous studies have consistently highlighted the positive influence of economic growth on tourism demand. Lee and Chang (2008) found that economic growth in Asian countries increases tourism arrivals by improving infrastructure and raising disposable incomes. Seetanah (2011) observed that higher national income significantly boosts tourism demand, especially in island economies. Tang and Tan (2015) provided global evidence for the tourism-led growth hypothesis, demonstrating a strong connection between economic growth and tourism expansion. Similarly, Eugenio-Martin, Martín Morales, and Scarpa (2004) showed that countries experiencing higher economic growth attract more tourists due to improved services and facilities. Similarly, research by Blake, Sinclair, and Campos Soria (2006) and Crouch (2011) found that better economic conditions enhance tourism by increasing a destination’s competitiveness and appeal. Li, Song, and Witt (2005) identified economic factors as key drivers of tourism demand in their econometric analysis. Suresh and Senthilnathan (2014) highlighted the significant role of economic growth in promoting tourism in India, while Kim et al. (2008) demonstrated how cultural exports fueled by economic growth can boost tourism. Ravinthirakumaran et al. (2020) provided evidence from Sri Lanka, showing that economic growth positively impacts tourism demand through improved infrastructure and increased income levels.

The SDGs promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, influencing tourism by encouraging policies that balance economic benefits with environmental and social responsibilities. Goal 8, which focuses on sustained, inclusive, and sustainable growth, directly affects the tourism industry by supporting eco-friendly practices and ensuring decent work conditions. Research suggests that incorporating SDGs into tourism strategies enhances destination appeal and competitiveness by promoting sustainable resource use and minimizing environmental harm (Gössling et al., 2009; Hall, 2010). Furthermore, SDG 12, which emphasizes sustainable consumption and production, helps reduce tourism’s adverse effects on local ecosystems and communities (Bramwell & Lane, 2013). The adoption of SDG 13, which focuses on climate action, is vital as it encourages the tourism industry to implement strategies that lower carbon emissions and adapt to climate change (Gössling & Peeters, 2015). Research shows that countries integrating SDGs into their tourism policies experience more sustainable tourism growth, achieving long-term economic benefits while preserving natural and cultural resources (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Hall et al., 2020). While this discussion effectively links SDGs to sustainable tourism growth and highlights the need to balance economic, environmental, and social priorities, it could delve deeper into assessing the effectiveness of SDG implementation and measurement, particularly in fast-developing regions.

The SDGs are essential in shaping the link between economic growth and tourism demand by advocating for a balanced approach that ensures tourism development promotes sustainable and equitable growth. They encourage tourism policies that focus on environmental sustainability, social inclusion, and long-term economic resilience, helping to reduce risks linked to rapid tourism growth, such as resource depletion and social inequalities (Hall, 2010; Gössling et al., 2009). By promoting practices that safeguard local environments and communities while generating economic benefits, the SDGs align tourism with global sustainability objectives. The SDGs also offer a framework to tackle challenges posed by global economic shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring that tourism growth remains resilient and adaptable to evolving global conditions (Hall et al., 2020). By incorporating the SDGs into tourism strategies, countries can achieve sustainable tourism growth that not only fosters economic development but also protects cultural and natural resources for future generations (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020; Bianchi, 2004). Thus, the SDGs act as a moderating framework for the relationship between economic growth and tourism, ensuring that growth is both sustainable and equitable (Bianchi, 2004; Tang & Tan, 2015).

Identifying research gaps is essential for deepening our understanding of the complex relationship between economic growth and tourism in Asia. First, there is a lack of research focusing on how the SDGs impact tourism growth, particularly within the Asian context (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020). This includes examining the moderating role of sustainability goals in the connection between economic growth and tourism (Bianchi, 2004; Bramwell & Lane, 2013). Second, existing literature has not adequately explored how factors such as export effects and national income mediate the relationship between tourism and economic growth, leaving a gap in understanding these key dynamics (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Lim, 1997). Third, there is a need for more detailed studies that consider the distinct economic, cultural, and environmental contexts of different Asian countries. Existing research often generalizes findings without properly distinguishing the varying impacts of tourism across these diverse settings (Tang & Tan, 2015). A more nuanced approach would offer a deeper understanding of how different factors influence countries with unique contexts. By examining these differences, researchers can identify specific patterns and dynamics that may be overlooked in broader, generalized studies.

Theoretical background

The selection of determinants in Eq. (1) is based on a combination of recent insights and previous scholarly research, underpinned by a solid theoretical framework. According to Oh (2005), there is a connection between economic growth and the increase in tourism, which is captured in the Economic Driven Tourism Growth Hypothesis (EDTGH). This hypothesis suggests that economic growth and development are fundamental to fostering the expansion of the tourism industry (Oh, 2005). It argues that for tourism to shift from a sector dependent on the economy to one that drives economic growth, it must be preceded by efforts to enhance overall economic development. A nation’s significant economic progress is expected to meet two key conditions: the improvement of both physical and human capital, and the creation of a more favorable economic environment that supports the growth of the tourism sector (Antonakakis et al., 2015). In contrast, the Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis (TLGH) suggests that tourism can significantly drive economic growth by creating jobs, attracting investments, and boosting foreign exchange earnings (Balaguer & Cantavella-Jordá, 2002; Dritsakis, 2004). This theory is particularly relevant to Asian economies, where tourism has been a key factor in economic development. For instance, countries like Thailand and Malaysia have used tourism to diversify their economies and stimulate growth (Tang & Tan, 2015). The combination of these theories with sustainability principles leads to the development of the Sustainable Tourism Growth Hypothesis (STGH). This hypothesis argues that sustainable practices in tourism—such as using renewable energy, promoting financial inclusion, and enhancing energy efficiency—can reduce environmental impacts while fostering economic resilience and growth. The study aims to examine these relationships, offering empirical support for the STGH and extending the relevance of the EDTGH and TLGH in a sustainability context (Gössling et al., 2009; Hall, 2010; Beer et al., 2017).

The SDGs are designed to promote sustainable tourism growth by encouraging practices that protect the environment and benefit local communities (Gössling et al., 2009). As destinations work to balance economic benefits with environmental and social responsibilities, sustainable tourism practices have become increasingly essential (Hall, 2010). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need for resilient tourism models that can endure global economic disruptions, further emphasizing the importance of sustainability (Hall et al., 2020). Several factors are linked to economic growth, such as increased exports, which can improve a country’s global reputation and attractiveness, and higher national income, which can drive domestic tourism (Lee, 2012). Tourism is closely connected to renewable energy use, financial inclusion, and energy efficiency, creating a broad impact at both local and global levels. Incorporating renewable energy into tourism infrastructure, such as solar panels for hotels, wind energy for resorts, and bioenergy for rural lodges, not only reduces carbon emissions but also appeals to the growing number of eco-conscious travelers, boosting the sector’s sustainability and appeal (Beer et al., 2017). Financial inclusion is crucial in this context as it provides small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the tourism industry with better access to financial resources and services. This enables these businesses to invest in renewable energy technologies and energy-efficient practices, reducing operational costs and enhancing competitiveness (Gopalan & Khalid, 2022). Additionally, improving energy efficiency in tourism operations—through measures like smart energy management systems, retrofitting buildings with energy-saving technologies, and optimizing transportation logistics—helps reduce overall energy consumption (José-Luis et al., 2021). This not only supports global sustainability goals but also generates significant cost savings, which can be reinvested into local economies, fostering economic growth. Therefore, the integration of tourism, renewable energy, financial inclusion, and energy efficiency not only enhances environmental sustainability but also strengthens economic resilience and promotes inclusive growth within the tourism sector.

The theoretical innovation of this study is its examination of the interconnectedness between tourism, renewable energy consumption, financial inclusion, and energy efficiency as essential drivers of sustainable economic growth. In contrast to traditional approaches that treat these factors separately, this study introduces an integrated framework that views these elements as mutually reinforcing contributors to both tourism demand and overall economic resilience.

This integrated approach builds on the EDTGH and the TLGH by adding sustainability factors that are increasingly important considering global environmental issues (Gössling et al., 2009; Hall, 2010). By emphasizing the crucial role of renewable energy in reducing carbon emissions and attracting eco-conscious travelers, as well as the significance of financial inclusion in empowering SMEs within the tourism sector, this study presents a new theoretical perspective that aligns with the SDGs (Beer et al., 2017; Gopalan & Khalid, 2022).

In addition, this study introduces the STGH, which suggests that incorporating sustainability practices into tourism not only improves environmental results but also drives economic growth by attracting investments, encouraging innovation, and generating jobs in the green economy. This theoretical innovation addresses the growing need for a more comprehensive understanding of tourism’s role in sustainable development, as emphasized in recent literature (Hall et al., 2020; José-Luis et al., 2021).

By introducing this new framework, the study adds to the ongoing discussion on sustainable tourism and economic growth, presenting a thorough model that can be used in future empirical research to assess its validity and impact in various contexts. This approach not only addresses a gap in current literature but also offers valuable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders aiming to balance economic development with environmental sustainability.

Methods

Variable selection

In this study, the dependent variable is tourism demand, which is quantified through international tourism receipts. These receipts are widely recognized as the most suitable proxy for measuring inbound tourism expenditure within a country (Kumar, 2013). Additionally, the study utilizes economic growth as a dependent variable, represented by Gross Domestic Product (Rasool et al., 2021; Alfaisal et al., 2024). Economic growth is examined due to its fundamental role in increasing disposable income and improving infrastructure, both of which boost tourism. Moderating variable SDGs are included to understand how sustainable development practices influence tourism, reflecting global commitments to economic, social, and environmental goals. Control variables such as: Renewable energy consumption is assessed for its potential to attract eco-conscious tourists and promote environmental sustainability. Financial inclusion is analyzed for its role in enabling broader participation in the tourism economy by providing accessible financial services. Lastly, energy efficiency is studied for its contribution to reducing operational costs and appealing to environmentally conscious travelers, thereby enhancing a destination’s competitiveness. These variables collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted factors driving tourism development in Asia. Table 1 showed the selection and definition of variables.

Measurement of variables

Tourism demand is measured by international tourism receipts in current U.S. dollars, reflecting the total spending by international visitors. Economic growth is represented by Gross Domestic Products (GDP) per capita or real GDP, measured in current U.S. dollars. The SDG score is quantified on a scale from 1 to 100. Renewable energy consumption is measured as a percentage of total final energy consumption, while energy efficiency is assessed by GDP per unit of energy use, expressed in constant 2017 Public Private Partnership (PPP) per kilogram of oil equivalent. Financial inclusion (FIN) is determined by using principal component analysis detailed in Appendix 1a, emphasizing the significance of the first principal component (Comp-1) in explaining 65.2% of the variance. This component, driven by Automated Teller Machine (ATM) and Corporate and Business Banking (CBB) with respective contributions of 70.7% and 70.7% serves as the foundation for constructing the financial inclusion for 35 Asian Countries.

This study focuses on 35 Asian countries (See appendix 2), chosen for their geographical, economic, and political relevance in understanding the relationship between tourism and economic growth. These countries collectively account for a significant portion of global tourism activity and economic development, making them representative of the broader Asian context. Asia’s diverse yet interconnected economies, ranging from high-income to low-income nations, provide a unique setting to analyze how economic growth influences tourism demand and vice versa. Politically, many of these nations are actively aligning their development strategies with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), making them suitable for exploring the moderating role of SDGs in this dynamic.

The selected countries share several commonalities that justify their inclusion in this study. They exhibit rapid economic growth, evolving tourism sectors, and a shared emphasis on sustainable development. Additionally, they display considerable heterogeneity in tourism demand levels (low, medium, and high), allowing for a comprehensive analysis of asymmetric relationships. These commonalities enable meaningful comparisons and robust conclusions, ensuring that the findings are relevant and applicable to the broader Asian region and beyond.

Model

Based on the research questions outlined in the study’s introduction section guide us to develop a comprehensive framework for evaluating the nexus between economic growth (EG) and tourism (TOUR). In pursuit of this objective, we develop a model using multivariate estimation that encompasses TOUR, EG, and a series of control variables. The empirical models formulated in this paper is structured as follows:

In the equation, the parameters \({\beta }_{1}\) to \({\beta }_{5}\) assess the nexus of the independent variables (EG, SDG, REC, FIN, and EE) on the dependent variable (TOUR). Given that our research objective is to accurately examine the causal nexus of economic growth (EG) on tourism (TOUR), \({\beta }_{1}\) holds particular significance. It represents the elastic association between EG and TOUR, and we anticipate it to be positive, indicating a positive impact of EG on TOUR. Additionally, we incorporate two-way fixed impacts denoted as πi and μt. The error term is represented by εit.

Mediating nexus

We also investigate the influence of EG on TOUR, aiming to elucidate the mechanisms through which EG affects TOUR. According to Sundari and Ariani (2020), EG facilitates export and elevates gross national income (lnGNI), while export (lnEXP) activity in turn enhances EG. Consequently, our analysis will focus on examining these two effects: exports and national income. To achieve this, we employ the equations (Eqs. 2 to 5) to conduct mediating nexus regressions.

Moderating nexus

After examining the direct relationship between SDG and TOUR, we aim to investigate the moderating effect of SDG on the EG-TOUR relationship. This analysis is conducted in several steps: first, we include both EG and SDG in the estimation model (Eq. 6); second, we introduce an interaction term between EG and SDG, then estimate its effect on TOUR (Eq. 7); and finally, we incorporate both SDG and the interaction term into the estimation model (Eq. 8).

Econometric approach

In the panel data analysis, we followed the methodology illustrated in Fig. 1. To determine the presence of cross-sectional dependence, we applied the cross-sectional dependence test as described by Pesaran (2007), which evaluates the correlation between time-series data across different countries. Moreover, we performed the slope homogeneity test to determine whether the slope coefficients are heterogeneous or homogeneous across the sample countries. (Pesaran & Yamagata, 2008; Blomquist & Westerlund, 2013). Given that CSD and slope homogeneity can influence the reliability of conventional panel unit root tests, we employed a second-generation unit root test (CIPS and CADF), also proposed by Pesaran (2007). A panel cointegration test, as proposed by Westerlund (2007), was utilized to measure the long-term linear association among the series variables. After validating these basic assumptions, this study utilizes two approaches to assess both linear and nonlinear relationships between the variables. For linear relationships, we employed Instrumental Variables Generalized Method of Moments (IV-GMM), while panel quantile regression was utilized for non-linear relationships. Our study includes a range of control variables related to sustainable development, financial development, energy consumption, and energy efficiency. However, the exclusion of certain variables that may influence tourism demand could result in omitted variable bias. Additionally, there is a potential for reverse causality among the variables. Given these considerations, traditional methods such as Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), Random Effects (RE), Fixed Effects (FE), or Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) may produce estimates that lack efficiency and consistency due to endogeneity issues. However, FGLS remains a viable alternative, particularly for addressing challenges stemming from unknown heteroscedasticity (Zhao et al., 2021). Conversely, the IV-GMM technique emerges as a robust solution for endogeneity concerns, utilizing orthogonal conditions to generate reliable and effective estimators (Islam, 2024). Additionally, consistent with the approach taken by Acheampong et al. (2020, 2021), we employ the lagged term of the independent variable (EG) as the instrumental variable (IV) within the IV-GMM model. Upon establishing the presence of a cointegration relationship, we employed the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) and Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS) models to estimate long-run effects, addressing concerns like serial correlation and endogeneity (Bhattacharya et al., 2016). To capture both long-run and short-run effects, Pesaran and Smith (1995) advocated the use of pooled mean-group (PMG) estimators for dynamic heterogeneous panel cointegration analysis.

Moreover, to account for potential asymmetric and nonlinear relationships between variables, this study employs panel quantile regression. Conventional panel data estimators may produce biased and inefficient results when faced with dataset heterogeneity (Işık et al., 2024a; Allard et al., 2018; Kocak et al., 2019). Additionally, these traditional approaches often focus solely on the distribution’s midpoint, neglecting its extreme points (Kocak et al., 2019). In contrast, the quantile regression method, pioneered by Koenker, Bassett (1978), considers data heterogeneity and offers results for both the midpoint and extremes of the distribution (Kocak et al., 2019). Finally, our study utilizes IV-GMM estimation to explore the moderating effect of SDG on the EG-TOUR relationship.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for the six variables—TOUR, SDG, EG, REC, FIN, and EE—show varying degrees of central tendency and distribution characteristics in Table 2. TOUR has a mean of 9.268 and moderate variability (SD = 0.809), with a slight left skew (−0.508) and a near-normal distribution (Kurtosis = 2.600). SDG shows minimal variability (SD = 0.044), a mean of 1.803, and a slightly negative skew (−0.257). EG has a mean of 3.602, with slight positive skew (0.287) and near-normal distribution (Kurtosis = 2.199). REC has high variability (SD = 0.979), a mean of 0.819, and a significant negative skew (−1.151), indicating a long-left tail and peaked distribution (Kurtosis = 4.105). FIN has a mean close to 0, wide range (SD = 1.071), strong positive skew (2.040), and extreme outliers (Kurtosis = 7.337). EE shows low variability (SD = 0.167), a mean of 0.961, slight positive skew (0.205), and a near-normal distribution (Kurtosis = 2.344). These statistics reflect the central tendencies, variability, and distribution shapes of the data.

Correlation analysis

The correlation matrix in Table 3 shows the relationships between six variables: TOUR (Tourism), SDG (Sustainable Development Goals), EG (Economic Growth), REC (Renewable Energy Consumption), FIN (Financial Inclusion), and EE (Energy Efficiency). TOUR is moderately positively correlated with SDG (0.334) and EG (0.496) but negatively correlated with REC (−0.270). SDG shows moderate positive correlations with EG (0.450) and FIN (0.324), while REC is strongly negatively correlated with EG (−0.737) but positively associated with EE (0.305). FIN has weak positive correlations with SDG (0.324) and EG (0.339), but negligible relationships with TOUR (0.062) and EE (0.023). EE demonstrates weak positive correlations with REC (0.305), TOUR (0.122), and SDG (0.155). These findings suggest nuanced interactions between these variables, highlighting areas of synergy and trade-offs, particularly between economic growth, renewable energy, and financial inclusion.

CSD and slope homogeneity test

Tables 4 and 5 present the results of the cross-sectional dependence (CSD) test and the slope homogeneity test. The CSD test results strongly indicate the presence of cross-sectional dependence in the panel data, as evidenced by the highly significant p-values (0.0000) across all three tests: the Breusch-Pagan LM test (2847.855), the Pesaran scaled LM test (65.307), and the Pesaran CD test (35.967). The rejection of the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level confirms substantial correlations among residuals across cross-sectional units, underscoring the necessity of employing estimation techniques that account for CSD to avoid biased and inconsistent results. Similarly, the Slope Homogeneity Test reveals significant heterogeneity in the slope coefficients across units. Both the mean-variance bias-adjusted ∆ test (8.349, p-value 0.000) and its HAC-adjusted version (4.564, p-value 0.000) reject the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity. The ∆_adj test and its HAC-adjusted counterpart (10.885 and 5.951, both with p-values of 0.000) further confirm that the slopes vary significantly across units, highlighting the need to account for this heterogeneity in the analysis.

Unit root test

The unit root test results presented in Table 6 indicate that some variables are non-stationary at levels but become stationary at first differences, suggesting they are integrated of order one. Specifically, TOUR and REC exhibit significant stationarity at both the level and first difference across both the Cross-sectionally augmented Im-Pesaran-Shin (CIPS) and Cross-sectional Augmented Dickey-Fuller (CADF) tests, while EG, FIN, and EE are non-stationary at levels but become stationary at first differences. SDG shows mixed results, with significant stationarity at first difference in both tests, although only the CIPS test indicates significance at the level. These findings suggest that all variables are stationary at first difference in both models.

Cointegration test

Table 7 presents the results of four cointegration tests as outlined by Westerlund (2007), which assess the null hypothesis of no cointegration within panel data. The four tests conducted are Gt, Ga, Pt, and Pa. The findings reveal that while the Gt and Ga tests fail to reject the null hypothesis, the Pt and Pa tests do reject it, thereby providing evidence of cointegration. This suggests the presence of a long-term equilibrium relationship between tourism and the specified variables. Consequently, these results confirm that the fundamental assumptions required for estimating cointegration regression are satisfied.

Baseline regression

Table 8 presents the baseline regression results obtained using ordinary least squares (OLS), fixed effects (FE), random effects (RE), feasible generalized least squares (FGLS), and instrumental variable generalized method of moments (IV-GMM) methods. These models allow for a comparative assessment to evaluate the robustness of the findings. Given the presence of endogeneity (Appendix 1b) and dataset heterogeneity (Table 3), the IV-GMM model is selected as the preferred approach due to its ability to address these issues effectively (Acheampong et al., 2020; Acheampong et al., 2021). The absence of heteroskedasticity is confirmed (Appendix 1c). The analysis primarily focuses on the results from the IV-GMM model, as presented in the final column of Table 8.

Before interpreting the IV-GMM coefficients, the model’s reliability is assessed using the LM test and the Wald test. The test statistics, shown in the last three rows of Table 6, confirm that the instrumental variable (IV) is strong, meaning it is neither under-identified nor weak.

The results indicate that economic growth (EG) is positively associated with tourism across all models, suggesting a consistent relationship. Specifically, in the IV-GMM model, the coefficient is 0.771, implying that a 1% increase in EG is associated with a 0.771% increase in tourism. This positive relationship may be attributed to improved economic conditions, increased disposable income, and enhanced infrastructure development, which collectively support tourism expansion (Azam et al., 2021a; 2021b; Shafique et al., 2020). However, causality should be interpreted cautiously, as other factors may also influence tourism growth.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) index exhibits a significant and positive relationship with tourism. A 1% increase in the SDG index is associated with a 2.598% rise in tourism. This relationship may stem from improvements in infrastructure, social services, and environmental sustainability, all of which contribute to making a country a more attractive tourist destination (Ali et al., 2024a). The findings align with previous studies indicating that progress in SDGs enhances tourism potential by improving areas such as transportation, clean energy, and safety (Ali et al., 2024b). However, while the positive link is robust, other external factors may also contribute to tourism growth.

Renewable Energy Consumption (REC) shows a significant and positive relationship with tourism in most models, including the IV-GMM model, where the coefficient is 0.110. This suggests that a 1% increase in REC is associated with a 0.110% increase in tourism. While this relationship appears positive, further investigation is needed to establish whether it is driven by sustainable tourism preferences, energy policy initiatives, or broader economic trends (Azam et al., 2021c).

Financial Inclusion (FIN) exhibits a significant but negative relationship with tourism, with a coefficient of −0.132 in the IV-GMM model. This suggests that a 1% increase in financial inclusion is associated with a 0.132% decrease in tourism. This result may indicate potential financial constraints or instability affecting travel behavior (Ali et al., 2023). However, additional research is necessary to determine whether this relationship is causal or driven by other confounding economic factors.

Finally, energy efficiency (EE) is found to have a significant and positive association with tourism, with a 1% increase in EE corresponding to a 0.562% increase in tourism. This suggests that destinations with improved energy efficiency may attract more tourists, potentially due to lower operational costs for businesses and increased appeal to sustainability-conscious travelers (Ali et al., 2024c). Nonetheless, further research is needed to examine the long-term implications of energy efficiency on tourism demand.

Overall, these findings underscore the interconnected nature of economic, financial, and policy factors in shaping tourism dynamics. While the results provide valuable insights, further investigation is warranted to establish causal relationships and assess potential external influences.

Robustness check

The baseline regression results reveal a positive impact of EG, SDG, and EE on tourism, while FIN exhibits a negative relationship with tourism. To test the robustness of these findings, two robustness checks were conducted.

First, an alternative dependent variable, international tourism expenditures for travel items, was used to represent tourism demand. Table 9 indicates that EG has a positive and significant effect on tourism, with a 1% change in EG associated with a 1.022% increase in TOUR. FIN shows a negative relationship with TOUR, where a 1% change in FIN corresponds to a 0.085% decrease in TOUR. Secondly, an alternative independent variable, specifically GDP (constant 2015 US$), was used to represent economic growth. Table 10 indicates that economic growth has a significant and positive effect on tourism, where a 1% increase in economic growth is associated with a 0.635% increase in tourism. Similarly, SDG and EE also exhibit significant and positive relationships with tourism. A 1% change in SDG is associated with a 4.423% increase in tourism, while a 1% change in EE corresponds to a 0.727% increase in tourism. Conversely, REC demonstrates a significant but negative relationship with tourism, with a 1% change in REC associated with a 0.084% decrease in tourism. It is noteworthy that the coefficients of EG remain significant and positive across all five models, even when alternative dependent and independent variables are applied. This consistency suggests that the relationship between EG and TOUR is robust across different model specifications. Similar findings regarding the relationship between economic growth and tourism have been documented across various countries. Research conducted in India (Suresh & Senthilnathan, 2014), China (Li, Song, & Witt, 2005), Barbados (Lorde et al., 2011), South Korea (Chen & Chiou-Wei, 2009), and Malaysia (Lean & Tang, 2010) highlight a significant relationship between economic growth and tourism. While these studies provide evidence of a positive relationship between economic growth and tourism, it is important to acknowledge that regional and structural differences may influence the strength and nature of this relationship across different economies.

Long run estimation

Table 11 shows the long-run estimation using two models: FMOLS and DOLS. The application of the FMOLS and DOLS models reveals a significant long-term impact of economic growth on tourism demand. Specifically, a 1% increase in economic growth is associated with a 0.83% rise in tourism demand when utilizing the FMOLS model and a 0.56% increase when employing the DOLS model. Additionally, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) exhibit a significant and positive relationship with tourism demand, where a 1% improvement in SDG indicators corresponds to a 2.84% increase in tourism demand using the FMOLS model and a 7.66% increase using the DOLS model. Energy efficiency (EE) also demonstrates a significant and positive relationship with tourism demand, with a 1% improvement in energy efficiency leading to a 0.30% increase in tourism demand according to the FMOLS model. However, this variable is omitted in the DOLS model. Other factors, such as renewable energy consumption and financial inclusion, do not exhibit a significant relationship with tourism demand based on the results from both the FMOLS and DOLS models.

PMG/ARDL estimation

Table 12 provides the results of the PMG/Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) estimation, offering insights into both short-term and long-term relationships among the variables. The analysis indicates a significant positive long-term effect of economic growth on tourism demand, with a 1% increase in economic growth leading to a 1.09% rise in tourism demand over the long run. However, no short-term relationship between economic growth and tourism demand is observed. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) exhibit a negative long-term relationship with tourism demand, where a 1% change in SDGs results in a 1.69% decrease in tourism demand. There is also no short-term relationship between SDGs and tourism demand. Renewable energy consumption demonstrates a significant negative relationship with tourism demand in both the short and long term. Specifically, a 1% change in renewable energy consumption leads to a 0.007% decrease in tourism demand in the long run and a 0.708% decrease in the short run. The results from the long-term estimation of economic growth, SDGs, and renewable energy consumption align with the findings from our preferred IV-GMM model, highlighting the robustness of our results.

Asymmetric relationship analysis

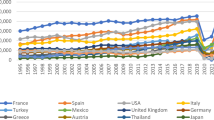

After analyzing the linear relationship and identifying a positive correlation between EG and TOUR, we are now keen to investigate the potential existence of a non-linear or asymmetric relationship. To explore this, we utilize the panel quantile regression model (see Table 13) to examine the non-linear effect of EG on TOUR. Panel quantile regression model is instrumental in determining the marginal effect of EG across various quantiles of TOUR. The results of the panel quantile regressions are presented in Table 13 and Fig. 2.

Economic growth and tourism demand

The research reveals a strong and consistent positive relationship between economic growth and tourism demand across various levels of tourism demand (low, mid, and high). This relationship holds true across all quantiles, from the 10th to the 90th percentile, indicating that regardless of the level of tourism demand, economic growth tends to boost tourism. This robustness across quantiles confirms the reliability of the primary finding. The results are consistent with previous studies, such as Po and Huang (2008), who also identified a nonlinear relationship between tourism and economic growth. Similarly, Muhtaseb and Daoud (2017) used nonlinear cointegration tests to find a bidirectional relationship, where not only does economic growth drive tourism demand, but tourism also contributes to economic growth.

SDGs and tourism demand

The study also finds that SDGs have a significant and positive impact on tourism demand, particularly when tourism demand is low. This indicates that as a region or country advances in its SDG performance, tourism demand increases, especially in areas with low tourism activity. The panel quantile regression further shows that at the 10th and 25th quantiles, the relationship between SDGs and tourism demand remains positive and significant. This suggests that even at lower levels of tourism demand, the influence of SDGs is beneficial.

Renewable energy consumption and tourism demand

For renewable energy consumption, a significant and positive relationship with tourism demand is observed, particularly when tourism demand is high. This suggests that regions with higher tourism activity can benefit from increased renewable energy consumption, perhaps due to the appeal of sustainability to environmentally conscious tourists. At higher quantiles (75th and 90th), this positive relationship continues to hold, indicating that renewable energy consumption is beneficial for tourism demand even when it is already at a higher level.

Financial inclusion and tourism demand

The relationship between financial inclusion and tourism demand is significant but negative across all levels of tourism demand (low, mid, high). This finding indicates that increased financial inclusion may not necessarily translate into higher tourism demand and could potentially be a deterrent. This might be due to various factors, such as the availability of alternative financial services that make traditional financial systems less critical for tourists. The negative relationship across all quantiles (10th to 90th) underscores this consistent trend.

Energy efficiency and tourism demand

Energy efficiency has a positive and significant relationship with tourism demand, particularly when tourism demand is moderately low and mid. The panel quantile regression reveals that at the 25th and 75th quantiles, energy efficiency positively impacts tourism demand. This suggests that improving energy efficiency can attract more tourists, likely due to the growing preference for destinations that prioritize sustainability.

The research also emphasizes that the nonlinear results are very similar to the linear results, which further validates the robustness of the primary findings. This consistency across different models and methodologies reinforces the reliability of the relationships identified between tourism demand and the various factors studied. Overall, these findings provide a comprehensive understanding of how different economic, environmental, and social factors interact with tourism demand across various levels, offering valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders in the tourism and related sectors.

Mediating effects

We employed two mediating variables to denote the effects of export and national income. Consequently, Eqs. 2 and 3 illustrate the impact of exports, as presented in the first and second columns of Table 14, while the impact of national income is shown in the third and fourth columns. Table 14 demonstrates the positive effect of EG on exports. Specifically, a 1% increase in EG corresponds to a 1.041% increase in exports. Furthermore, there is a positive relationship between exports and TOUR, with a 1% increase in export resulting in a 0.757% increase in TOUR. Regarding the second mechanism, there is a significant positive relationship between EG and national income. Specifically, a 1% increase in EG corresponds to a 0.885% increase in national income. Additionally, there is a positive nexus between national income and tourism, with a 1% increase in national income resulting in a 0.565% increase in TOUR. Our research findings align with similar results from other authors. The effects of economic growth on tourism demand are mediated by export effects and national income. Increased exports can enhance a country’s international reputation and attractiveness, thereby attracting more tourists (Eugenio-Martin et al., 2004). For example, the global rise of Korean pop culture, supported by the country’s export strategies, has significantly boosted tourism to South Korea (Kim et al., 2008). Additionally, higher national income increases domestic tourism, as people have more financial resources to spend on travel (Tang & Tan, 2015).

The moderating nexus of SDG

In addition to examining economic growth (EG), we observe a significant direct effect of sustainable development goals (SDG) on tourism (TOUR). The achievement of SDG is crucial for a country’s overall development. As evidenced in Table 8 (baseline regression), Table 9 (regression using an alternative dependent variable), and Table 12 (PMG/ARDL estimation) there is a direct and positive relationship between SDG and TOUR. However, when an alternative independent variable is employed in Table 10, the relationship between SDG and TOUR is also positive.

Table 15 presents the results of the moderation analysis, aligned with Eqs. 2–4, detailed in Columns I, II, and III, respectively. Initially, Column I reveals that both economic growth (EG) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) exhibit a significant and positive impact on tourism demand (TOUR), corroborating earlier findings in the literature.

In subsequent analyses, the interaction terms between EG and SDGs are introduced, revealing a more nuanced relationship. Specifically, the moderation analysis shows that SDGs not only independently contribute to TOUR but also amplify the positive effects of EG on TOUR. This suggests that as economies grow, the presence of strong SDG frameworks further enhances the attractiveness of tourist destinations, beyond what economic growth alone would achieve.

This positive moderation effect can be attributed to several factors. First, SDGs encourage sustainable practices that lead to the preservation of natural and cultural assets, which are key attractions for tourists. For instance, stringent environmental regulations (under SDG 12) ensure the conservation of landscapes and ecosystems, which are vital for eco-tourism. Similarly, efforts to build sustainable cities (SDG 11) contribute to safer, cleaner, and more culturally vibrant urban spaces, increasing their appeal to visitors.

Moreover, the promotion of “decent work” (SDG 8) within the tourism and hospitality sectors can improve service quality, leading to better tourist experience and higher satisfaction rates. This, in turn, creates a positive feedback loop where high-quality services attract more tourists, driving further economic growth and investment in the tourism sector. The interaction effect between EG and SDGs also implies that sustainable development practices are not just supplementary but integral to maximizing the benefits of economic growth in the tourism industry. By embedding sustainability into the core growth strategy, destinations can ensure that economic gains are durable and inclusive, leading to a more resilient tourism industry that can withstand economic downturns or environmental challenges. Furthermore, this integrated approach fosters a competitive advantage for destinations that prioritize SDGs, as they can market themselves as environmentally conscious and socially responsible, attracting a growing segment of tourists who value sustainability. This differentiation in the market can lead to increased tourism revenue and long-term economic prosperity.

The moderation effect of SDGs on the relationship between economic growth and tourism underscores the importance of aligning growth strategies with sustainable development goals. This alignment not only enhances the immediate economic benefits of tourism but also ensures that these benefits are sustained over the long term, contributing to a more robust and resilient tourism industry.

Conclusion

Using panel data from 35 Asian countries spanning from 2004 to 2020, this paper examines both the linear and nonlinear relationships between economic growth (EG) and tourism (TOUR). It also explores the mechanisms through which EG affects TOUR and the role of SDGs. The results provide several important insights.

Firstly, the study reveals a direct and asymmetric relationship between economic growth (EG) and tourism (TOUR). The key findings show strong evidence that EG positively influences TOUR, indicating that GDP growth drives increased tourism activity. Furthermore, the effect of EG on TOUR is more pronounced in countries with lower to mid-high levels of tourism development. Secondly, the paper explores the mechanisms through which EG affects TOUR. It finds that EG boosts TOUR indirectly by increasing exports and national income, highlighting the importance of both domestic and international income growth.

Additionally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) significantly enhance tourism growth by aligning with key factors that attract and benefit tourists. Improved infrastructure under SDGs 9 and 11 makes destinations more accessible, while environmental sustainability goals like SDGs 12 and 13 help preserve natural and cultural resources. Economic growth fostered by SDG 8 aids in creating tourism-related employment, and the protection of cultural heritage under SDG 11 enhances the attractiveness of historical sites. Furthermore, SDGs 1 and 2 contribute to community well-being by alleviating poverty and improving local living standards, while SDG 17 promotes global tourism partnerships. Thus, SDGs play a crucial role in sustaining and advancing tourism by integrating these diverse yet interconnected goals. The findings suggest that SDGs act as a moderating factor in the EG-TOUR relationship, indicating that the interplay between economic growth and sustainable development is essential for tourism expansion.

Policy implications

The findings suggest several policy recommendations to foster tourism development through economic growth. Governments in Asian countries should prioritize inclusive economic growth by investing in tourism-related infrastructure, such as airports, roads, and public transportation, to enhance accessibility and attract visitors. Leveraging economic growth for tourism development is essential, particularly for countries with lower to mid-high levels of tourism activity. This can be achieved by creating tourism products that appeal to both domestic and international travelers, promoting cultural heritage and natural attractions, and incentivizing private sector investments in tourism infrastructure like hotels and resorts. Additionally, export-led tourism strategies can strengthen the sector by promoting local goods and crafts or offering packages that combine cultural and shopping experiences.

Incorporating Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into tourism planning is vital for long-term growth. Governments should integrate SDG targets, such as developing resilient infrastructure (SDG 9 and 11), promoting eco-tourism (SDG 12 and 13), creating decent tourism-related jobs (SDG 8), and addressing poverty reduction (SDG 1 and 2) in tourist areas. Strengthening global partnerships, as emphasized in SDG 17, through streamlined visa processes, collaborative marketing, and joint initiatives can further boost regional and global tourism. Lastly, establishing a robust monitoring and evaluation framework to assess SDG impact on tourism development will help ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of these strategies. By implementing these recommendations, policymakers can align economic growth with sustainable tourism development in Asian countries.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, data availability and restrictions may impact the robustness of the findings, as the analysis is constrained by the quality, coverage, and frequency of existing datasets. This limitation may introduce biases or limit the generalizability of the results. Second, while the study explores the relationship between economic growth and tourism (EG-TOUR), potential issues with causality remain. The complexity of this relationship, including bidirectional causality and unobserved factors, suggests that future research should apply advanced econometric techniques, such as instrumental variable approaches or panel structural equation modeling, to mitigate endogeneity concerns. Third, the study primarily focuses on Asia, which limits its applicability to other regions with different economic structures, policy environments, and tourism dynamics. Expanding the geographic scope would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the EG-TOUR relationship across diverse contexts. Fourth, the study acknowledges the inherent complexity of nonlinearity and asymmetry in the EG-TOUR relationship. While it provides a broad exploration of impact mechanisms, deeper insights into specific mechanisms and tourism sub-sectors—such as eco-tourism, cultural tourism, and luxury tourism—are necessary for more targeted policy recommendations. Lastly, the study does not explicitly account for the impact of recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflicts, which have significantly influenced both tourism and economic growth. Future research should incorporate these factors to provide more relevant and timely insights.

Addressing these limitations in future studies will enhance the robustness of the findings and contribute to the development of more effective and sustainable tourism policies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the supplementary information section.

References

Acheampong AO, Amponsah M, Boateng E (2020) Does financial development mitigate carbon emissions? evidence from heterogeneous financial economies. Energy Econ 88:104768

Acheampong AO, Dzator J, Shahbaz M (2021) Empowering the powerless: does access to energy improve income inequality? Energy Econ 99:105288

Alfaisal A, Xia T, Kafeel K, Khan S (2024) Economic performance and carbon emissions: revisiting the role of tourism and energy efficiency for BRICS economies. Environ Dev Sustain https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04394-4

Ali MI, Ceh B, Salahuddin M (2023) The energy-growth nexus in Canada: new empirical insights. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30:122822–122839

Ali MI, Islam MM, Ceh B (2024b) Green versus grey: Impact of renewable and non-renewable energy usage on Canada’s growth trajectory in the context of internal and external forces. Sustain Futures 8:100258

Ali MI, Islam MM, Ceh B (2024a) Growth-environment nexus in Canada: Revisiting EKC via demand and supply dynamics. Energy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X241263833

Ali MI, Islam MM, Ceh B (2024c) Assessing the impact of three emission (3E) parameters on environmental quality in Canada: a provincial data analysis using the quantiles via moments approach. Int J Green Energy 22:551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2024.2421329

Allard A, Takman J, Uddin GS, Ahmed A (2018) The N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve: an empirical evaluation using a panel quantile regression approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:5848–5861

Antonakakis N, Dragouni M, Filis G (2015) How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Econ Model 44:142–155

Azam A, Rafiq M, Shafique M, Yuan J (2021a) Renewable electricity generation and economic growth nexus in developing countries: An ARDL approach. Eco Res Ekonomska Istraživanja 34:2423–2446

Azam A, Rafiq M, Shafique M, Ateeq M, Yuan J (2021b) Investigating the impact of renewable electricity consumption on sustainable economic development: a panel ARDL approach. Int J Green Energy 18:1185–1192

Azam A, Rafiq M, Shafique M, Zhang H, Ateeq M, Yuan J (2021c) Analyzing the relationship between economic growth and electricity consumption from renewable and non-renewable sources: fresh evidence from newly industrialized countries. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 44:100991

Balaguer J, Cantavella-Jordá M (2002) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl Econ 34:877–884

Beer M, Rybár R, Kaľavský M (2017) Renewable energy sources as an attractive element of industrial tourism. Curr Issues Tour 21:2147–2159

Bhattacharya M, Paramati SR, Ozturk I, Bhattacharya S (2016) The effect of renewable energy consumption on economic growth: evidence from top 38 countries. Appl Energy 162:733–741

Bianchi R (2004) Tourism restructuring and the politics of sustainability: a critical view from the European periphery (The Canary Islands). J Sustain Tour 12:495–529

Blake A, Sinclair MT, Campos Soria JA (2006) Tourism productivity: evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann Tour Res 33:1099–1120

Blomquist J, Westerlund J (2013) Testing slope homogeneity in large panels with serial correlation. Econ Lett 121:374–378

Bramwell B, Lane B (2013) Getting from here to there: systems change, behavioral change and sustainable tourism. J Sustain Tour 21:1–4

Chen CF, Chiou-Wei SZ (2009) Tourism expansion, tourism uncertainty and economic growth: New evidence from Taiwan and Korea. Tour Manag 30:812–818

Crouch GI (2011) Destination competitiveness: an analysis of determinant attributes. J Travel Res 50:27–45

Crouch GI, Ritchie JRB (1999) Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J Bus Res 44:137–152

Dritsakis N (2004) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: an empirical investigation for Greece using causality analysis. Tour Econ 10:305–316

Dwyer L, Forsyth P, Rao P (2000) The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: a comparison of 19 destinations. Tour Manag 21:9–22

Eugenio-Martin JL, Martín Morales N, Scarpa R (2004). Tourism and economic growth in Latin American countries: a panel data approach. Soc Sci Res Netw https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.504482

Gazi MAL, Islam H, Islam MA, Karim R, Momo SM, Senathirajah ARBS (2024). Unlocking sustainable development in East Asia Pacific and South Asia: an econometric exploration of ESG initiatives. Sustain Environ https://doi.org/10.1080/27658511.2024.2366558

Gopalan S, Khalid U (2022) How does financial inclusion influence tourism demand? empirical evidence from emerging markets and developing economies. Tour Recreat Res 49:639–653

Gössling S, Peeters P (2015) Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J Sustain Tour 23:639–659

Gössling S, Hall CM, Weaver D (2009) Sustainable tourism futures: perspectives on systems, restructuring and innovations. Routledge

Hall CM (2010) Crisis events in tourism: subjects of crisis in tourism. Curr Issues Tour 13:401–417

Hall CM, Scott D, Gössling S (2020) Pandemics, transformations and tourism: be careful what you wish for. Tour Geogr 22:577–598

Higgins-Desbiolles F (2020) The elusiveness of sustainability in tourism: the culture-ideology of consumerism and its implications. Tour Hosp Res 20:117–130

Işık C, Bulut U, Ongan S, Islam H, Irfan M (2024a) Exploring how economic growth, renewable energy, internet usage, and mineral rents influence CO2 emissions: a panel quantile regression analysis for 27 OECD countries. Resour Policy 92:105025

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Sharif A, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2024f) Evaluating the effects of ECON-ESG on load capacity factor in G7 countries. J Environ Manag 360:121177

Işık C, Ongan S, Isla H, Pinzon S, Jabeen G (2024e) Navigating sustainability: unveiling the interconnected dynamics of ESG factors and SDGs in BRICS‐11. Sustain Dev https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2977

Işik C, Ongan S, Islam H (2024b) A new pathway to sustainability: Integrating economic dimension (ECON) into ESG factors as (ECON-ESG) and aligned with sustainable development goals (SDGs). J Ekonom https://doi.org/10.58251/ekonomi.1450860

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H (2024g) Global environmental sustainability: the role of economic, social, governance (ECON-SG) factors, climate policy uncertainty (EPU) and carbon emissions. Air Quality Atmos Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-024-01675-3

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Jabeen G, Pinzon S (2024c) Is economic growth in East Asia Pacific and South Asia ESG factors based and aligned growth? Sustain Dev https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2910

Işık C, Ongan S, Islam H, Menegaki AN (2024d) A roadmap for sustainable global supply chain distribution: Exploring the interplay of ECON-ESG factors, technological advancement and SDGs on natural resources. Resour Policy 95:105114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2024.105114

Islam H (2024) Nexus of economic, social, and environmental factors on sustainable development goals: The moderating role of technological advancement and green innovation. Innov Green Dev 4:100183

Islam H, Rana M, Saha S, Khatun T, Ritu MR, Islam MR (2023) Factors influencing the adoption of cryptocurrency in Bangladesh: an investigation using the technology acceptance model (TAM). Technol Sustain 2:423–443

Islam H, Soumia L, Rana M, Madavarapu JB, Saha S (2024) Nexus between perception, purpose of use, technical challenges and satisfaction for mobile financial services: theory and empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Technol Sustain https://doi.org/10.1108/techs-10-2023-0040

José-Luis, SO, Francisco, SC, Javier, SRG, María, PRGD (2021) Energy efficiency in tourism sector: eco-innovation measures and energy. In: Borge-Diez D, Rosales-Asensio E (ed) Energy services fundamentals financing, 1st edn. Academic Press, pp 258

Kim SS, Agrusa J, Chon K, Cho Y (2008) The effects of Korean pop culture on Japanese tourism demand to South Korea. Tour Manag 28:902–911

Kocak E, Ulucak R, Dedeoğlu M, Ulucak ZŞ (2019) Is there a trade-off between sustainable society targets in Sub-Saharan Africa? Sustain Cities Soc 51:101705

Koenker R, Bassett Jr G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46:33–50

Kumar RR (2013) Exploring the role of technology, tourism and financial development: an empirical study of Vietnam. Qual Quant 48:2881–2898

Lean HH, Tang CF (2010) Is the tourism‐led growth hypothesis stable for Malaysia? a note. Int J Tour Res 12:375–378

Lee CC (2012) Tourism demand modeling: a time-varying parameter approach. J Hosp Tour Res 36:135–156

Lee CC, Chang CP (2008) Tourism development and economic growth: a closer look at panels. Tour Manag 29:180–192

Li G, Song H, Witt SF (2005) Recent developments in econometric modeling and forecasting. J Travel Res 44:82–99

Lim C (1997) Review of international tourism demand models. Ann Tour Res 24:835–849

Lorde T, Francis B, Drakes L (2011) Tourism services exports and economic growth in Barbados. Int Trade J 25:205–232

Muhtaseb BMA, Daoud H-E (2017) Tourism and economic growth in Jordan: evidence from linear and nonlinear frameworks. Int J Econ Financ Issues 7:214–223

Oh CO (2005) The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tour Manag 26:39–44

Pesaran M, Smith R (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Econ 68:79–113

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross‐section dependence. J Appl Econ 22:265–312

Pesaran MH, Yamagata T (2008) Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J Econ 142:50–93

Po WC, Huang BN (2008) Tourism development and economic growth–a nonlinear approach. Phys A Stat Mech Its Appl 387:5535–5542

Rasool H, Maqbool S, Tarique M (2021) The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis. Future Bus https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Ravinthirakumaran N, Sharmila A, Thiruchchenthurnathan T (2020) Economic growth and tourism: an ARDL bound testing approach for Sri Lanka. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 7:137–145

SDG Index (2024) Sustainable development index. https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/

Seetanah B (2011) Assessing the dynamic economic impact of tourism for island economies. Ann Tour Res 38:291–308

Shafique M, Azam A, Rafiq M, Luo X (2020) Evaluating the relationship between freight transport, economic prosperity, urbanization, and CO2 emissions: evidence from Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea. Sustainability 12:10664

Song H, Dwyer L, Li G, Cao Z (2012) Tourism economics research: a review and assessment. Ann Tour Res 39:1653–1682

Sukserm T, Ussahawanitchakit P (2017) The effect of destination image on tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: a case study of Khon Kaen, Thailand. J Tour Manag Res 4:1–11

Sundari MS, Ariani M (2020) Measuring Economic Growth Through National Income Elasticity. Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2022). https://doi.org/10.2991/aebmr.k.200127.038

Suresh SS, Senthilnathan S (2014) Tourism development and economic growth in India: a vector autoregressive model. Int J Bus Econ Dev 2:61–69

Tang CF, Tan EC (2015) Tourism-led growth hypothesis: a new global evidence. Tour Manag 42:1–10

WDI (2024) World development indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Accessed June 2 2020

Westerlund J (2007) Testing for error correction in panel data*. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 69:709–748

Zhao C, Wang K, Dong X, Dong K (2021) Is smart transportation associated with reduced carbon emissions? The case of China. Energy Econ 105:105715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105715

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Hasibul Islam; methodology: Hasibul Islam; software: Hasibul Islam; investigation, original draft preparation: Hasibul Islam, Tusher Ghosh, Sihan Liu, Kaniz Habiba Afrin, Muhammad Sibt e Ali.; review and editing: Hasibul Islam, Tusher Ghosh, Kaniz Habiba Afrin, Muhammad Sibt e Ali; review and editing after review: Hasibul Islam, Sihan Liu, Tusher Ghosh, Kaniz Habiba Afrin, Muhammad Sibt e Ali.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Islam, H., Ghosh, T. et al. Exploring the nexus between economic growth and tourism demand: the role of sustainable development goals. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 441 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04733-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04733-y