Abstract

Aesthetic preferences vary widely among individuals and across cultures. These culture-specific aesthetic preferences are reflected in the environment, artistic behaviour, and consumer choices. People have the ability to infer the aesthetic preferences of others within their own culture through their Theory of Aesthetic Preferences, which is a subcategory of the Theory of Mind. An important question is whether people can also infer aesthetic preferences across different cultures. This study aimed to investigate aesthetic preference and aesthetic inference, as well as the underlying mental processes of beauty judgements such as affective and cognitive responses, by comparing ratings on beauty, affective, and cognitive dimensions from participants in China (n = 84) and Germany (n = 82). The results suggest that aesthetic preferences are more dependent on the stimuli than on the culture. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that beauty judgements, as well as intra- and inter-cultural beauty inferences, are generally associated with positive emotions, while the relationship between beauty judgement and cognitive stimulation seems to be culture-specific. Overall, our findings provide evidence for a universal human beauty response mechanism that is linked to positive emotions and support the idea of a universal Theory of Aesthetic Preferences. This theory enables people to infer the aesthetic preferences of others both within and across different cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artworks serve as universal records of human history (Aubert et al., 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2018), while also representing the diversity of human cultures through their distinct domains, appearances, and representations (Dutton, 2005; van Damme, 2000). In this context, culture is defined as a “set of attitudes, behaviours, and symbols shared by a large group of people and usually communicated from one generation to the next” (Shiraev and Levy, 2016, p. 25). The dual nature of art, being both universal and highly varied in terms of cultural diversity, raises a fundamental question in the field of empirical aesthetics (e.g., Nadal and Chatterjee, 2018; Sharman, 1997; Van den Braembussche, 2008): to what extent is aesthetic experience and preference universal? Aesthetic preferences are indicated by individual aesthetic judgements of works of art and other aesthetic objects as being more or less beautiful or otherwise, for instance, emotionally or cognitively pleasing (VandenBos, 2007).

Recent dual-process models of aesthetic experience (e.g., Graf and Landwehr, 2015, 2017; Leder et al., 2004; Locher et al., 2008; Redies, 2015) propose that there is a rapid perceptual processing of low-level stimulus features that is universal among humans, followed by a controlled cognitive processing of higher-level features that depends on the individual’s personal experiences and socio-cultural background (e.g., Hanquinet et al., 2014; Woodward and Emmison, 2001; Masuda et al., 2008; Nisbett and Masuda, 2003). These models also suggest that aesthetic judgements, such as a judgement of beauty or liking, can be based on an initial emotional pleasure triggered by perceptual processing as well as on an intellectual pleasure resulting from interest or cognitive mastery during cognitive processing. Importantly, it has been suggested that beauty primarily and universally results from positive emotions (see Armstrong and Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Brielmann and Pelli, 2017, 2019; Redies, 2015; Vartanian and Goel, 2004). Nevertheless, results from cognitive processing can override initial emotional responses (Leder et al., 2004). Based on these assumptions, it can be concluded that beauty judgements based on emotions caused by early perceptual processing should be universal among humans, whereas beauty judgements based on controlled cognitive processing should largely depend on the individual and their socio-cultural background.

In the present cross-cultural study, we investigated the extent to which these conclusions hold. To achieve this objective, we not only compared the beauty judgements of individuals from different cultural backgrounds but also analysed their ability to infer the aesthetic preferences of others, including affective and cognitive preferences as well as their beauty judgements. This ability was considered a proxy for a universal understanding, representing the common ground of aesthetic preferences. In the following sections, we will provide a brief overview of related studies and introduce relevant concepts before reporting our own results.

Cross-cultural studies on basic aesthetic features

Abundant evidence indicates that there are basic properties of artwork (see Berlyne, 1971), such as symmetry (e.g., Birkhoff, 1933; Osborne, 1986; Ramachandran and Hirstein, 1999), balance (e.g., Arnheim, 1954, 1983; Hübner and Fillinger, 2016, 2019), spatial composition (e.g., Sammartino and Palmer, 2012), colour combination (e.g., Schloss and Palmer, 2011), etc. (for an overview, see Palmer and Griscom, 2013), that are considered aesthetic universals, meaning they are perceived and evaluated in the same way by all human beings. If such universals exist, individuals from different cultural backgrounds should have similar basic aesthetic preferences. To test this prediction, various cross-cultural studies have been conducted since the 1950s (for a detailed overview, see Che et al., 2018). These studies have revealed, for instance, general preferences for symmetry and a certain level of complexity in geometric patterns and abstract forms (Bode et al., 2017; Farley and Ahn, 1973; Uduehi, 1995) and a shared preference for neatly organised, i.e., ordered compositions of real-world objects (Van Geert et al., 2024). Another study found shared preferences for curved versus angular contours in real-world objects among individuals from Ghana, Mexico, and Spain (Gómez-Puerto et al., 2018). Furthermore, a study reported a high degree of agreement in aesthetic preferences between BaKwele individuals, a tribe from western equatorial Africa, and art experts from the U.S. when it came to photographs of traditional BaKwele wooden masks (Child and Siroto, 1965).

Additionally, no significant differences in aesthetic preference were found between Egyptian and English participants, as well as between Japanese and English participants, regarding 90 black and white Birkhoff polygons (Eysenck and Iwawaki, 1971; Soueif and Eysenck, 1971, 1972). Moreover, there were no differences in aesthetic sensitivity between Japanese and English participants, as well as between Chinese and English participants, when it came to judging the aesthetic quality of 42 pairs of nonrepresentational drawings by the German artist K.O. Götz (Iwawaki et al., 1979; Eysenck et al., 1984). Finally, numerous studies have reported universal colour preferences for bluish tones and an aversion to yellow-greenish tones (Hurlbert and Ling, 2007; Ou et al., 2004; Palmer and Schloss, 2010; Sorokowski et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, the results of the studies mentioned are difficult to compare and interpret, mainly due to methodological reasons. For instance, only stimulus sets from one cultural background were used instead of including stimulus sets from all participants’ cultures. Additionally, the stimulus sets did not include artworks but rather simple patterns or photographs of everyday objects with specific applications.

Cross-cultural studies on high-level aesthetic features and artworks

In accordance with the proposition that aesthetic judgements are often based not only on low-level perceptual features but also on controlled cognitive processing, it has been shown that aesthetic preferences for artworks usually depend on a mixture of both, the evaluation of low- and high-level features (Iigaya et al., 2021). When scrutinising the research on aesthetic preferences for artworks, differences on the individual level (see Vessel et al., 2018), and between individuals of distinct cultures becomes evident. For example, a cross-cultural study, investigating Chinese and Western participants´ assessments for paintings from both cultures, showed stronger beauty judgements for artworks from their own compared to artworks from the other culture (Bao et al., 2016). This pattern was also observed in a fMRI study examining European and Chinese participants (Yang et al., 2019). Here, investigators observed stronger neuronal activation when participants viewed art from their own cultural background. Masuda and colleagues (2008) found culture-specific variations in the composition, style, and content of drawings and photographs created by U.S. Americans and East Asian participants. Furthermore, also preference judgements for these photographs, composed according to the East Asian or Western scene composition traditions, were reported to be culture-dependent. In another study, Chinese and English participants showed distinct aesthetic preferences for photographs of their culture-specific urban landscapes (Chen et al., 2016). Furthermore, cross-cultural differences in the degree of preference for fascinating images were found between Western and Chinese participants (Van Geert et al., 2024). Fascination was defined as “high in order and high in complexity” (see Van Geert and Wagemans, 2021). In the study, the Western participants preferred more fascinating images. Contrarily, the Chinese participants preferred images that were rated as less complex, hence simpler.

Even studies on colour preferences highlighted culture-dependent differences (for a historical and socio-cultural overview, see Aslam, 2006; Madden et al., 2000; Park & Guerin, 2002). Differences in colour preference have been reported, for instance, between British participants and participants from the Himba tribe in northern rural Namibia (Taylor et al., 2013). While the British participants preferred bluish tones and had an aversion for yellow-greenish tones, i.e., colour preferences actually assumed to be universal (see Palmer and Schloss, 2010), the Himba had a low preference for bluish tones but a high preference for saturated red, orange, yellow, chartreuse and green hues. Differences in colour preference have also been observed between Chinese and European participants (Braun and Doerschner, 2019). Chinese observers preferred shades of red, blue, and yellow, followed by orange, whereas European participants preferred shades of red and green, followed by blue, yellow, and purple. Also, Chinese participants preferred slightly darker colours and disliked strong colour contrasts. Differences in colour preferences have been explained, for example, by differences in object associations (Taylor et al., 2013), gender-stereotypes (LoBue and DeLoache, 2011), the relativity of colour appearance values (Ou et al., 2012), as well as culture-specific assigned meaning (Madden et al., 2000; Park & Guerin, 2002; Saito, 2015) and culturally specific personal experiences (Yokosawa et al., 2016).

Causes for cultural specificity of aesthetic preferences

The culture-specific differences in aesthetic preference for higher-level features have been attributed to different thinking styles (Ji et al., 2012; Nisbett & Masuda, 2003; Nisbett et al., 2008), cognitive and perceptual configurations (Miyamoto et al., 2006), and overall aesthetic experience (Liu et al., 2013; Sharman, 1997). Particularly, differences between East Asian and Western cultures are emphasised in this regard. Even though all people seem to be able to apply both thinking styles (Norenzayan et al., 2002), the Western thinking style has been described as primarily analytic, focusing on object categorisation and logical rule finding, while the Chinese thinking style is considered holistic, focusing on the overall relationships among objects and events (Nisbett et al., 2001; for an overview, see Smith, 2023; for critique on this dichotomy, see, e.g., Mercier, 2011; Hung and Lane, 2016).

Culture-dependent differences in cognition (Han and Northoff, 2008; Ji et al., 2012; Shiraev and Levy, 2016) suggest that although basic perceptual mechanisms for aesthetic evaluation may be universal, humans do not necessarily create and appraise artworks equally. For instance, it has been argued that Chinese traditional paintings typically provide holistic, contextual information, while Western traditional paintings concentrate on salient and discrete objects, according to the assumed differences in thinking styles (Miyamoto et al., 2006; Nisbett and Masuda, 2003). Furthermore, artworks, as cultural symbols, may not only be less preferred but also difficult to evaluate and interpret by persons of other cultures (Masuda et al., 2008).

A theory of aesthetic preferences

It has been hypothesised that culture-dependent aesthetic preferences are influenced by individuals’ interaction with their cultural environment (Redies, 2015; Sharman, 1997). For example, repeated exposure to artworks enhances preference for them (Cutting, 2003; Zajonc, 1968; 2001) and facilitates cultural learning, due to shared experiences, feelings, and expression of social values (Dissanayake, 1980). This not only aids in understanding the semantics, symbolism, and historical context of artworks but also supports knowledge of their general appeal among individuals who share the same culture.

In this regard, Miller and Hübner (2020, 2023) demonstrated that individuals are capable of making accurate intra-cultural inferences about beauty judgements, as well as the affective and cognitive responses to artworks from their own cultural background. Importantly, their studies considered beauty judgements in relation to both affective and cognitive evaluations of artworks, as suggested by recent models of aesthetic appreciation (e.g., Graf and Landwehr, 2015, 2017; Leder et al., 2004; Locher et al., 2008; Redies, 2015). On the other hand, beauty inferences were mainly associated with inferring other individuals’ affective responses. Thus, participants primarily relied on their affective cognition (Ong et al., 2015) to infer beauty. Based on this, the authors assumed that laypersons primarily attribute beauty to a positive emotional response to art. Overall, Miller and Hübner (2020) concluded that aesthetic inference depends on a Theory of Aesthetic Preferences (TAP), which implies that people generally understand that others have distinct aesthetic preferences, those beauty judgements may differ, and that individuals may be emotionally affected or cognitively stimulated by the experience of art in different ways. This TAP should be considered a subcategory of the Theory of Mind (ToM) (Premack and Woodruff, 1978). ToM refers to “the understanding each person has about his or her own and other people’s experience and mental processes… Inferences and predictions based on this make mutual understanding possible and enable our complex social interactions” (Matsumoto, 2009, p. 542).

Interestingly, experimental evidence has shown that the ability to learn about other people’s preferences is primarily dependent on repeated interpersonal interaction (Kimbrough et al., 2017). Additionally, the cultural theory of preference formation suggests that preferences are established through human interaction (Wildavsky, 1987). In this regard, individuals from collectivistic cultures, where the group is prioritised over the individual, may have an advantage in inferring aesthetic preferences within their own culture compared to individuals from individualistic cultures, which have weaker group boundaries (Wildavsky, 1987; also, Hofstede, 2011). Collectivism has been described as “behaviour based on concerns for other people, traditions, and values they share together”, whereas individualism is referred to as “complex behaviour based on concern for oneself and one’s immediate family or primary group as opposed to concern for other groups to which one belongs” (Shiraev and Levy, 2016, p. 25). Additionally, the advantage of people from collectivistic societies to correctly infer the aesthetic preferences of other persons within their culture might arise from more frequent and intense interactions with in-group members, leading to stronger social relationships (Shiraev and Levy, 2016, p. 279).

However, it has been argued that the ability to attribute preferences to others is important in environments with persistent novel information and enables individuals to adjust their behaviour for effective interaction (Robalino and Robson, 2016). Therefore, it can be assumed that the inference of other people’s aesthetic preferences is also possible across cultures, potentially supported by universal mechanisms of perception and valuation (Che et al., 2018; Redies, 2015), as well as general Theory of Mind (ToM) abilities (Bradford et al., 2018; Shahaeian et al., 2011). Consequently, it is reasonable to assume the existence of a universal Theory of Aesthetic Preferences (TAP).

The present study

In the present study, we investigated the universality and cultural specificity of aesthetic preference and aesthetic inference, as well as the underlying mental mechanisms. We used a new approach that combined the traditional method of comparing beauty ratings between individuals from different cultural backgrounds with comparing their ability to assess the aesthetic preferences of people from another cultural background. To achieve this objective, we collected data from two groups with highly different cultural backgrounds: Germans, representing members of a truly individualistic culture, and Chinese, representing members of a collectivistic culture (see Minkov and Kaasa, 2022).

In the first experiment, we collected aesthetic judgements and inferences from German and Chinese participants for 24 Western artworks. These artworks had already been used as stimuli in two previous studies with German participants (see Miller and Hübner, 2020, 2023). To address the effect of culture-specific aesthetic preferences and to balance the possible effects of the specific cultural selection of artworks, we conducted a second experiment. In this experiment, different groups of German and Chinese participants judged 24 Chinese artworks.

We collected aesthetic judgements on three aesthetic dimensions. On the one hand, judgements related directly to the aesthetics of the objects, i.e., their beauty. On the other hand, judgements are related rather to the subjective experience, such as judgements about the individual´s emotional reaction to the artwork or the artwork´s potential for cognitive stimulation (see Miller and Hübner, 2020, 2023).

All participants assessed the respective artwork sets in three ways: (1) through a self-assessment, where they provided their subjective aesthetic preferences, (2) through an intra-cultural assessment, where they inferred the aesthetic preferences of individuals from their own culture, and (3) through an inter-cultural assessment, where they inferred the aesthetic preferences of individuals from the other culture.

These three assessments allowed us to investigate three hypotheses: (1) Beauty judgement is related to both affective and cognitive stimulus evaluation. In contrast, beauty inference is only related to affect inference. Both kinds of judgements should be independent of the viewer’s cultural background or the arts origin. (2) Intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities are superior to inter-cultural aesthetic inference abilities. Additionally, Chinese participants may have better intra-cultural inference abilities compared to German participants, possibly due to their collective culture system. (3) Art from one’s own culture is preferred to art from another culture.

Experiment 1

Design of Experiment 1

In the first experiment, participants from Germany and China evaluated 24 artworks from Western culture in three different ways. First, they completed a self-assessment where they indicated their subjective aesthetic preferences. Then, they conducted an intra-cultural assessment, where they evaluated the aesthetic preferences of individuals from their own cultural backgrounds. Finally, they conducted an inter-cultural assessment, where they evaluated the aesthetic preferences of individuals from the other cultural background, respectively. During each assessment, participants judged the artworks based on three dimensions: beauty, affect, and cognition. They answered questions about the beauty of the artworks, their emotional reactions, and the thoughts that the artworks provoked (refer to Fig. 1).

Methods

Participants

In view of our experimental design, we planned to use linear mixed-effect models. We based our sample size estimates on a previous study with a similar design (Miller and Hübner, 2020). Accordingly, we chose a sample size of about 40 participants per cultural group. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the University of Konstanz, as well as the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments (World Medical Association, 2013). Participants confirmed their consensus when they registered for the online recruiting system and signed their confirmation to participate in the experiment. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any consequences.

German participants

A total of 42 German students (31 female, Mage = 26.0, SD = 7.97) from the University of Konstanz, Germany, participated in this study. They were recruited through an online recruiting system (Greiner, 2015) and provided informed consent prior to participation. As compensation, participants received a 5 Euros Amazon voucher. There was no special sampling strategy. Of the many students who were informed about the experiment, those who opted in first took part. No participant had to be excluded from further analysis. It should be noted that the German participants did not have a professional background in the arts and were, therefore, considered as laypeople.

Chinese participants

A total of 41 Chinese students (30 female, Mage = 20.1, SD = 0.88) were recruited at the Qingdao University, China, through a Chinese online recruiting system (https://www.wjx.cn/) in the same way as the German sample. No participant had to be excluded from further analysis. As a compensation, participants received 35 RMB (~5 Euros) cash. It is important to note that these participants did not have any professional background in the arts and were considered laypeople.

Stimuli

Twenty-four photographs of Western paintings were used as stimuli in this experiment. The stimulus set, compiled by Chatterjee and colleagues (2010), consists of a wide range of artists, dates of origin, content, style, and popularity. The sets include both traditional and modern art, as well as figural (portraits, landscape, and still-lives) and abstract art (see Supplementary, Appendix A, Table 1). To ensure consistency, all images were scaled to a height of 600 pixels, with varying widths, and had a resolution of 72 dpi for online display. The images were presented in online questionnaires created using SoSci Survey (Greiner, 2015), a professional tool for conducting online surveys. We used the SoSci Survey Neutral Layout, which can be found at www.soscisurvey.de, for the layout of the questionnaire. Each image of an artwork appeared on a separate webpage, centred on the screen, with a white background. Unfortunately, due to the wide range of colours in the artworks, contrast equalisation was not possible.

Assessments

The experiment consisted of three assessments: an initial self-assessment, a subsequent intra-cultural assessment, and a final inter-cultural assessment. In the self-assessment, participants were asked to express their own subjective aesthetic preferences. For the intra-cultural assessment, participants were required to consider the perspective of others from their own cultural background and make inferences about their aesthetic preferences. Similarly, in the inter-cultural assessment, participants were asked to adopt the perspective of individuals from the other cultural background and infer their aesthetic preferences accordingly (see Supplementary, Appendix B for Chinese and German texts with English translations).

Aesthetic dimensions

In each assessment, participants evaluated the stimuli based on their beauty, emotional valence, and thought-provoking potential (cf. Hager et al., 2012; Miller and Hübner, 2020, 2023). The beauty dimension ranged from “not at all” to “very much”. Participants indicated the emotional valence induced by the artwork on a scale from “negative” to “positive”. On the cognitive dimension, participants indicated the extent to which they found the artwork thought-provoking, ranging from “not at all” to “very much”. The corresponding numeric values on the scale ranged from 1 to 101 for beauty and cognitive scales, and from −50 to 50 for the affective scale. A value of zero indicated no specific emotional valence induced by the artwork. Both artworks and scales were presented in a randomised order to control for order and familiarity effects.

The instructions and questions were initially translated from German to English, and then further translated into Chinese with the assistance of a native Chinese speaker fluent in German. The questionnaire was reviewed by a Chinese investigator at the University in China who is proficient in English and German to ensure accurate translation (see Sechrest et al., 1972).

Procedure

After enrolling in the experiment, participants were sent a link to an online questionnaire. The questionnaire provided information about the experiment, and participants began by answering socio-demographic questions and questions about their art expertise. These questions aimed to determine if participants were laypeople or had professional qualifications or experience in art. They were asked about their frequency of visiting art exhibitions, galleries, or museums, as well as how often they sought information about art in print and online media. These questions were asked to ensure that we were studying individuals without professional art backgrounds.

Next, participants were asked to indicate their own aesthetic preferences on three aesthetic dimensions. They made aesthetic judgements by using three separate continuous sliding scales, positioned below each artwork, following the method described by Treiblmaier and Filzmoser (2011). The scales were 334 pixels wide and 40 pixels high, with hidden numbers. There was no time limit, and participants could proceed to the next artwork by clicking a “next” button.

After completing the self-assessment, participants were instructed for the second part of the experiment. In this part, they were asked to judge the aesthetic preferences of other individuals from their own culture. The procedure for this part was the same as the self-assessment. In the final part of the experiment, participants were asked to indicate the aesthetic preferences of individuals from other cultures. To help participants emphasise with individuals from the other culture, they were shown a picture of a group of people from that culture before making their judgements.

The specific order of assessments was carefully chosen to control for an anchoring effect (Kahneman et al., 1982). Our hypothesis was that individuals use their own aesthetic preferences as a reference point to make inferences about the aesthetic preferences of others. Additionally, we assumed that participants compare the aesthetic preferences of individuals from their own culture with those from another culture (see Heine et al., 2002). Therefore, we first asked participants to assess their own preferences, followed by collecting their intra-cultural aesthetic inferences, and finally, their inter-cultural aesthetic inferences.

Data analysis strategies

First, descriptive and inferential statistics were reported to provide an overview of the dataset and to make first inferences about our two populations´ (Chinese, Germans) aesthetic preferences.

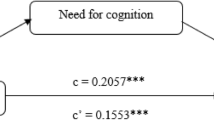

To test hypothesis 1 that beauty relates to both affective and cognitive stimulus assessments, regardless of a person´s cultural background and the art´s origin, we conducted a linear mixed-effects analysis using individual data points from the self-assessments. An analogous analysis was also applied in the second experiment, making results comparable. Using mixed-effects models, we were able to include random effects parameters to account for dependencies among related data points, thus controlling for the stochastic variability within the random-effects factors (e.g., participants, artworks) (see Singmann and Kellen, 2019).

Our second hypothesis that beauty inference is more closely related to affective inference than to cognitive inference was tested with the same linear mixed-effects model, using data from the intra- and inter-cultural assessments.

Our third hypothesis about intra- and inter-cultural beauty inference abilities, respectively, were tested with linear mixed-effects models using difference scores between participants´ inferences for individuals from their own culture (intra) or the other culture (inter) and the respective groups´ average judgements. The results give information on the question of whether intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities are superior to inter-cultural aesthetic inference abilities and whether Chinese participants may have superior intra-cultural inference abilities compared to German participants.

Results

Descriptive and inferential statistics

The mean values of aesthetic judgements for the two participant groups are presented in Table 1. This table also includes the corresponding interrater consistency, as measure by Cronbach’s alpha values. To calculate Cronbach´s alphas, we used the psych::alpha package in R (R Core Team, 2016). As shown, the consistency was satisfactory for each aesthetic dimension (see Bland and Altman, 1997).

On average, the German group rated the Western artworks as less thought-provoking compared to the Chinese group, t(43.7) = −3.16, p = 0.003. However, there was no significant difference in the judged beauty, t(42) = −1.80, p = 0.08, or emotional valence between the German and Chinese participants, t(39.4) = −0.29, p = 0.77.

Beauty judgement

To test our hypothesis that the judgement of beauty relates to both affective and cognitive judgements, regardless of a person´s cultural background, we conducted a linear mixed-effects analysis with Maximum Likelihood estimation (usage of lme4, Bates et al., 2015), implemented in R. This analysis was performed using individual data points from self-assessments. We had random intercepts for participants, to account for interindividual differences in aesthetic judgements, as well as for artworks to account for specific effects. The model included fixed effects for cultural groups and the affective and cognitive judgement scores. We also examined interaction effects between cultural groups and aesthetic judgements.

To ensure meaningful zero points (see Enders and Tofighi, 2007, p. 121), we applied grand mean centreing to the raw data points for each participant group, separately. Degrees of freedom were calculated using Satterthwaite’s approximations for the t-test, along with corresponding p-values.

The results of the analysis showed that both affective judgements and cognitive judgements significantly predicted participants´ beauty judgements (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). Cultural group did not have a significant effect. However, there was a significant interaction effect between cultural groups and cognitive judgements, suggesting that the impact of cognitive judgements on beauty judgements was stronger for German participants compared to Chinese participants.

To quantify the partial R2 for fixed effect predictors based on linear mixed-effects model fits, we used the partR2 package in R (Stoffel et al., 2021). The results showed that the affective judgements explained 29% of the variance in beauty judgements, while the cognitive judgements explained 4% of the variance. To calculate the variance explained by the fixed effects alone, as well as the variance explained by both fixed and random effects, we used the MuMln package in R (Barton, 2020). The fixed effects accounted for 36% of the variance in beauty judgement, while the combination of fixed and random effects accounted for 48% of the variance.

Aesthetic inference

Intra-cultural inference: In this section, we examined how participants from the same culture would rate the beauty, emotional valence, and thought provocation of the 24 artworks. Based on previous findings (Miller and Hübner, 2020), we hypothesised that beauty inference is more closely related to affective inference than cognitive inference.

To analyse beauty inference within the same culture, we used the same linear mixed-effects model that was used to analyse the self-assessments, using data from the intra-culture assessments. The results showed that both affective inferences and cognitive inferences significantly predicted beauty inferences (refer to Fig. 3 and Table 3). However, affective inference accounted for 38% of the variance in beauty inference, while cognitive inference only accounted for 2%. Cultural group did not have a significant effect, although there was a significant interaction between the cultural group and cognitive inference. This interaction indicated that the German group’s cognitive inferences were more strongly related to the beauty inferences they made for individuals from their own culture compared to the Chinese participants. The fixed effects accounted for 42% of the variance in beauty inferences. When considering both fixed and random effects together, they accounted for 49% of the variance in beauty inferences.

Inter-cultural inference: Next, we examined how participants inferred how people from other cultures would rate the beauty, emotional valence, and thought provocation of the 24 artworks.

Our results focused on the relationship between beauty inference and affective and cognitive inference. They indicated that both affective inferences and cognitive inferences significantly predicted beauty inferences for people from other cultures (see Fig. 4 and Table 3). The affective inference accounted for 26% of the variance in beauty inference, while the cognitive inference accounted for 9%. It is important to note that cultural groups also had a significant impact on beauty inferences, with weaker connections found among German participants. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction effect between cultural groups and affective inferences. This indicates that the emotional valence of people from the other culture was more strongly associated with beauty judgements for German participants compared to Chinese participants. Overall, the fixed effects explained 35% of the variance in beauty inferences, while both fixed and random effects together explained 41%.

Aesthetic inference abilities

According to hypothesis 2, we predicted that intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities would be superior to inter-cultural aesthetic inference abilities. Additionally, we hypothesised that Chinese participants would demonstrate better intra-cultural inference abilities compared to German participants due to their collective culture system. Therefore, we examined the effects of the inference condition (intra-/inter-cultural) and cultural group (Chinese/German) on aesthetic inference abilities.

Aesthetic inference abilities were measured as the difference scores between participants´ inferences for individuals from their own culture (intra) or the other culture (inter) and the respective groups´ average judgements (see Table 4). Lower difference scores indicated better inference abilities. Using a linear mixed effects model, we analysed how the difference scores (inference ability) depended on the inference condition (intra-cultural, inter-cultural), the cultural group, and any possible interaction between them. The analysis was conducted for all three aesthetic dimensions.

Regarding beauty, the analysis showed that the inference condition had a significant impact on the inference abilities, with stronger intra-cultural inferences (see Fig. 5 and Table 5). Cultural groups did not have a significant effect. However, there was a significant interaction between the inference condition and cultural group, suggesting that the German group had better inter-cultural inference abilities compared to the Chinese group. The fixed effects accounted for 2% of the variance in beauty inference abilities. When considering both fixed and random effects together, they accounted for 20% of the variance in beauty inference abilities.

Moving on to affective inferences, intra-cultural inference abilities once again outperformed inter-cultural inference abilities. Cultural group did not have a significant effect, but there was a significant interaction between the inference condition and cultural group. Once again, the German group had superior inter-cultural inference abilities. The fixed effects accounted for 1% of the variance in affective inferences abilities. Fixed and random effects together, they accounted for 27% of the variance in affective inferences abilities.

In terms of cognitive inferences, the inference condition also had a significant impact on inference abilities, with stronger intra-cultural inference abilities. Cultural group did not have an effect, but there was a significant interaction between the inference condition and cultural group. The German group once again demonstrated superior inter-cultural inference abilities compared to the Chinese group. The fixed effects accounted for 1% of the variance in cognitive inference abilities. Fixed and random effects together accounted for 25% of the variance in cognitive inference abilities.

Discussion

In this first experiment, we investigated how German and Chinese participants judged the beauty, emotional valence, and thought provocation of Western artworks. We also explored their ability to infer the aesthetic judgements of people from their own culture and from their respective other cultures.

As suggested by various researchers in empirical aesthetics (e.g., Fechner, 1876; Graf and Landwehr, 2015, 2017; Leder and Nadal, 2014; Locher et al., 2008; Nadal and Chatterjee, 2018), our results support the idea that beauty judgements are related to both affective and cognitive judgement of the stimuli. This finding confirms previous research on the aesthetic preference formation of German participants (see Miller and Hübner, 2020, 2023) and extends it to Chinese participants. However, our results also indicate a cultural difference in the extent to which affective and cognitive judgements relate to beauty judgements. While both cultural groups showed a strong relationship between affective judgements and beauty judgements, the relation of cognitive judgements to beauty judgements was significantly lower for Chinese participants compared to German participants. Additionally, Miller and Hübner (2023) reported a main effect of the affective judgement on beauty judgements, but they observed differences in the relationship between affective and cognitive judgements and beauty judgements between female and male participants. Based on our findings, we conclude that beauty judgements are primarily driven by a positive affective response, while the relation of cognitive judgement to beauty judgements appears to be more specific to cultural group.

Furthermore, the investigation into aesthetic inference also uncovered differences between the cultural groups. When inferring beauty judgements for individuals from their own culture, both groups believed that beauty is primarily related to others’ emotional evaluation, with a lesser emphasis on their cognitive evaluation. However, German participants considered the cognitive evaluation to have a stronger impact on the beauty judgements of individuals from their own culture compared to Chinese participants. This finding contradicts the results of Miller and Hübner’s (2020) study, where beauty inference was solely linked to emotional inference. Nonetheless, the current results demonstrate a more accurate infrence ability of the German participants, as their self-assessment revealed that cognitive evaluation is also related to their beauty judgements.

Regarding beauty inferences for individuals from the other culture, both groups believed that others’ beauty judgements predominantly rely on their emotional judgements. In this regard, German participants assumed an even stronger connection between Chinese individuals’ beauty judgements and their emotional evaluation compared to the Chinese participants. Once again, all participants agreed that others’ cognitive evaluation has only a minor impact on their beauty judgements.

Moreover, we confirmed the hypothesis that intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities are superior to inter-cultural inference abilities, regardless of the cultural group. Interestingly, however, the German participants were significantly better at inferring the aesthetic preferences of individuals from other cultures compared to the Chinese participants. This result may be attributed to the German participants´ expertise in the presented stimuli, which were Western artworks, or, conversely, the difficulty the Chinese participants had in inferring the aesthetic preferences of Germans for Western art, likely due to a lack of cultural knowledge (see Masuda et al., 2008). Furthermore, it has been suggested that individuals from collectivistic cultures perceive outgroup members as even more distant from themselves compared to individuals from individualistic cultures (see Triandis et al., 1990). Consequently, it is possible that the Chinese participants, as representatives of a collectivistic culture, perceived Germans as even more distant from themselves, thus facing more difficulties in inferring their aesthetic preferences.

Finally, our results did not support the hypothesis that aesthetic preferences are stronger for art from ones´ own cultural background compared to another cultural background, as reported by Bao et al. (2016) and Yang et al. (2019). In this experiment, the cultural group was not a significant predictor of beauty judgements for Western artworks.

Experiment 2

The finding that German participants outperformed Chinese participants in inferring the aesthetic preferences of Chinese participants appears to contradict the notion that the processes involved in making beauty judgements and inferences are applicable across different cultures, despite the cultural background of the artworks (see Miller and Hübner, 2020, 2023). To explore whether the use of Western artworks as stimuli influenced the results in Experiment 1 in favour of German participants, we conducted a second experiment using 24 Chinese artworks. The research design of this second experiment followed a similar between-subjects design as Experiment 1 (see research design of Experiment 1). Additionally, data handling and statistical analyses were carried out in a comparable manner to the procedures in Experiment 1.

Participants

A total of 40 German participants (34 female, Mage = 25.0, SD = 6.87) and 43 Chinese students (36 female, Mage = 20.1, SD = 0.45), who did not participate in Experiment 1, took part in Experiment 2. These participants had no professional background in the arts and were therefore considered as laypeople.

Stimuli

Twenty-four photographs of Chinese paintings from “The Chinese Art Book”, published by PHAIDON (Phaidon Press Limited, 2013), were used as stimuli in this experiment. Similar to the Western artworks, the set included a wide range of artists, dates of origin, content, styles, and levels of popularity (see Supplementary, Appendix A, Table 2).

Results

Descriptive and inferential statistics

The mean values of aesthetic judgements from both participant groups are presented in Table 6. The interrater consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha value, was satisfactory for both participant groups (see Bland and Altman, 1997).

Similar to Experiment 1, the German group rated the Chinese artworks as less thought-provoking compared to the Chinese group, t(36.5) = −3.40, p = 0.002. However, there was no significant difference in the perceived beauty, t(45.0) = −0.84, p = 0.40, or emotional valence between the German and Chinese participants, t(46) = −0.56, p = 0.60.

Beauty judgement

Upon analysing the formation of beauty judgements in Chinese art, our findings indicate that both affective judgements and cognitive judgements significantly related to beauty judgements (refer to Fig. 6 and Table 7). Cultural group, on the other hand, did not have a significant impact. Similar to Experiment 1, there was a notable interaction effect between cultural group and cognitive judgements, suggesting that cognitive judgements had a stronger effect on the beauty judgements of German participants compared to Chinese participants. Affective judgements accounted for 25% of the variance in beauty judgements, while cognitive judgements explained 4%. The fixed effects contributed to 36% of the variance and, when combined with random effects, explained 50% of the variance in beauty judgements.

Aesthetic inference

Intra-cultural inference: We initially evaluated participants’ inferences of how persons from their own culture would rate the beauty, emotional valence, and thought-provoking nature of the 24 Chinese artworks.

When analysing the relationship between participants´ beauty inferences and their affective and cognitive inferences, the results indicated that both affective inferences and cognitive inferences significantly predicted beauty inferences (see Fig. 7 and Table 8). Affective inferences accounted for 28% of the variance, whereas the cognitive inferences accounted for less than 1% of the variance in beauty inferences. Cultural group also had a significant impact on beauty inferences significantly, with German participants demonstrating stronger correlations between inferences. The fixed effects accounted for 33% of the variance in beauty inferences. When considering fixed and random effects, a total of 47% of the variance in beauty inferences was explained.

Inter-cultural inference: The analysis of beauty inferences for people from the other culture revealed that both affective inferences as well as cognitive inferences had a significant impact on beauty inferences (see Fig. 8 and Table 8). However, while affective inferences accounted for 32% of the variance, cognitive inferences explained less than 1%. The cultural group also had a significant impact on beauty inferences, with stronger connections observed among German participants. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction effect between cultural groups and cognitive inferences, indicating that German participants attributed less importance to the cognitive judgements of individuals from the other culture when making beauty judgements compared to Chinese participants. The fixed effects accounted for 34% of the variability in beauty inferences, while the combined effect of fixed and random effects explained 42%.

Aesthetic inference abilities

When analysing the impact of the aesthetic inference condition on the aesthetic inference abilities of both cultural groups (see Table 9), it was found that there was a significant effect of the inference condition on participants’ beauty inference abilities. As hypothesised, the intra-cultural inference abilities were superior, as shown in Fig. 9 and Table 10. The cultural group itself did not have a significant effect, yet, there was also a significant interaction effect, indicating that the German participants had superior inter-cultural inference abilities. The fixed effects accounted for 2% of the variance in beauty inference abilities. When considering both fixed and random effects together, they accounted for 17% of the variance in beauty inference abilities.

In terms of affective inference abilities, the inference condition had a significant effect, once again demonstrating better intra-cultural inference abilities. The cultural group also had a significant effect. There was also a significant interaction effect indicating superior inter-cultural inference abilities of German participants. The inference condition accounted for 12% of the variance in affective inference ability, the cultural group accounted for 19% of the variance The fixed effects accounted for 31% of the variance in affective inferences abilities, fixed and random effects together accounted for 39% of the variance in affective inferences abilities.

In regard to cognitive inference abilities, the inference condition also had a significant effect, with superior intra-cultural inference abilities. The cultural group itself did not have a significant effect. However, there was a significant interaction effect, indicating that the German participants had superior inter-cultural inference abilities. The fixed effects accounted for 1% of the variance in cognitive inference abilities, and fixed and random effects together accounted for 25% of the variance in cognitive inference abilities.

Discussion

In Experiment 1, we discovered that German participants were more proficient than Chinese participants in assessing the aesthetic preferences of individuals from the other culture. To investigate whether this advantage was specific to the stimuli used, we conducted a second experiment using 24 Chinese artworks as stimuli. Apart from this difference, the second experiment closely resembled the first. This also provided us with an opportunity to examine the generalisability of our previous findings.

Most importantly, we were able to replicate the result from Experiment 1, which revealed that individuals’ beauty judgements relate to affective and cognitive evaluations of the stimulus, with a stronger overall effect of the affective evaluation. Additionally, similar to Experiment 1, the cognitive evaluation had a significantly stronger impact on the beauty judgements of the German participants compared to the Chinese participants. This finding supports our hypothesis that the correlation between cognitive evaluation and beauty judgement is group- (see Miller and Hübner, 2023) or culture-specific, irrespective of the cultural origin of the artworks.

Furthermore, we were able to replicate the results for all three aesthetic dimensions, demonstrating that individuals have superior intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities compared to inter-cultural inference abilities. Importantly, the results indicated that the German participants once again exhibited better cognitive inference skills when trying to understand the judgements of individuals from the other culture compared to Chinese participants.

Again, both cultural groups’ intra- and inter-cultural beauty inferences for Chinese artworks were much more strongly related to affective inferences than cognitive inferences. However, unlike in Experiment 1, the effect of cognitive inferences on beauty inferences was almost negligible for both groups and in both inference conditions. Furthermore, German participants considered the beauty judgements of individuals from the other culture to relate even less to their cognitive judgements compared to Chinese participants. This result supports the idea that beauty inference is primarily achieved through an inference of the affective judgement of art (see Miller and Hübner, 2020), which again appears to be independent of the art’s cultural background.

Finally, our hypothesis that aesthetic preferences are stronger for art from an individual’s own cultural background compared to another cultural background was not confirmed in Experiment 2, as the cultural group was not a significant predictor of beauty judgements for Chinese artworks.

General discussion

In this cross-cultural study between China and Germany, we investigated the universal and culture specific aspects of aesthetic preference and aesthetic inference. We used artworks from both cultures as stimuli. Recent aesthetic models (e.g., Graf and Landwehr, 2015, 2017; Leder et al., 2004; Locher et al., 2008; Redies, 2015) propose that the aesthetic experience involves both affective and cognitive states, which influence aesthetic preferences. It can be assumed that these states also play a role in aesthetic inferences. Therefore, we measured aesthetic preferences and inferences along three dimensions: beauty, affect, and cognition. In two separate experiments, German and Chinese participants rated their own aesthetic preferences for Western artworks (Experiment 1) and Chinese artworks (Experiment 2). They then inferred the aesthetic preferences of individuals from their own culture and from the other culture, respectively.

We formulated three hypotheses for this study: (1) Beauty judgement is universally related to both affective and cognitive judgement. However, beauty inference is universally related more to affective inference. (2) Intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities are superior to inter-cultural aesthetic inference abilities. People from collectivistic cultures, such as China, have generally better intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities. (3) Aesthetic preferences are stronger for art from one’s own cultural origin compared to art from another cultural origin.

Our first hypothesis was confirmed in both experiments. We found evidence that supports the idea, proposed by various researchers in the field (e.g., Cela-Conde et al., 2011; Leder and Nadal, 2014; Marković, 2012; Redies, 2015), that the aesthetic experience universally engages individuals emotionally and cognitively. Recent models of aesthetics suggest that beauty judgements depend on affective and cognitive evaluation mechanisms (e.g., Graf and Landwehr, 2015, 2017; Leder et al., 2004; Locher et al., 2008; Redies, 2015). However, our participants’ beauty judgements and beauty inferences were found to be more strongly related to affective rather than cognitive judgements. This indicates that beauty primarily relates to positive emotions, as suggested by other researchers in the field of aesthetics (see Armstrong and Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Brielmann and Pelli, 2017, 2019; Vartanian and Goel, 2004). Therefore, our results support the idea of a universal human beauty-responsive mechanism, which depends more on the perceptual processing of the visual attributes of artworks (Che et al., 2018; Redies, 2015) and the induction of positive emotional valence (Matsumoto et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2001), rather than on higher-level cognitive processes or the socio-cultural background of the viewer (Redies, 2015; Sharman, 1997).

Importantly, our results showed that the cognitive judgements related significantly stronger to beauty judgements of the German participants compared to the Chinese participants, regardless of the art’s origin. Additionally, when evaluating Western art, the German participants assumed that the other Germans’ beauty judgements were also related to their respective cognitive judgements. Whereas, the Chinese participants did not assume a relationship between the beauty judgements and the cognitive judgements of other Chinese individuals. Therefore, we conclude that the relationship between cognitive judgement and beauty judgement and inference is distinct between particular groups (see Miller and Hübner, 2023) and cultures. Differences and cultural diversity in human perception and cognition have been reported by many investigators working in the field of cross-cultural research (e.g., Han and Northoff, 2008; Miyamoto et al., 2006; Nisbett et al., 2008; Nisbett et al., 2001; Norenzayan et al., 2007; Varnum et al., 2010; for an overview, see Smith, 2023) It is assumed that human cognition is influenced by the sociocultural context and social orientation, which is considered to be rather independent in Western societies and interdependent in East Asian societies (see Varnum et al., 2010). Moreover, Westerners have been considered to predominantly present an analytic thinking style, whereas East Asians are considered to have a rather holistic cognition (Miyamoto et al., 2006; Nisbett and Masuda, 2003; Nisbett et al., 2001; Nisbett, 2003). It might be that the mainly analytic thinking style of German persons is reflected in the relation between cognitive judgement and the judgement of beauty.

Regarding the cultural differences between Chinese and German persons, we relied on Hofstede´s tool: Cultural Dimensions, Country Comparison. Hofstede Insights (https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool; Minkov and Kaasa, 2022). According to Hofstede Insights, among the greatest differences between Chinese and German persons are differences in individualism/collectivism. Individualism “…is the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members.” Collectivism has been described as “…behaviour based on concerns for other people, traditions, and values they share together…” (Shiraev and Levy, 2016, p. 25). Although we believe that there are other factors that also reflect cultural differences between German and Chinese persons (e.g., “Power Distance” and “Uncertainty Avoidance”, see Minkov and Kaasa, 2022), we think that differences in individualism versus collectivism are most likely to be reflected in differences in aesthetic preferences, since artworks are cultural products which are produced according to the tradition and values of a social group, and beauty standards might well reflect the degree of how strongly these traditions and values are shared.

Furthermore, both studies confirmed our second hypothesis that intra-cultural aesthetic inference abilities are superior to inter-cultural aesthetic inference abilities. However, the expectation that the Chinese participants would demonstrate superior intra-cultural inference abilities compared to the German participants, due to their collective culture system, was not supported. Interestingly, German participants performed significantly better in inferring inter-cultural aesthetic preferences on all three aesthetic dimensions when evaluating Chinese art, and on the cognitive dimension when evaluating Western art, compared to the Chinese participants. This result could be explained by the notion that individuals from collectivistic culture systems perceive outgroups as even more distant compared to individuals from individualistic culture systems (see Triandis et al., 1990), which might impede their ability to infer aesthetic preferences.

It has also been suggested that participants’ aesthetic preferences are stronger for art from their own cultural background compared to another cultural background (e.g., Bao et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Masuda et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2019). However, our results did not confirm this hypothesis. Neither the Chinese participants nor the German participants judged art from their own cultural background to be more beautiful compared to art from the other cultures (also, Darda and Cross, 2022). This result supports the idea of a universal human beauty response mechanism, as suggested by Redies (2015), which relates to the characteristics of the stimulus (Berlyne, 1971) and the viewer´s affective response to it (Armstrong and Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Brielmann and Pelli, 2017, 2019; Vartanian and Goel, 2004), rather than to effects of mere exposure (Zajonc, 1968, 2001) and cultural learning (Tomasello et al., 1993).

Interestingly, German participants, in general, assessed both sets of artworks as less thought-provoking compared to the Chinese participants. Nevertheless, the beauty and affective judgements were similar for both cultural groups. These results also support the assumption of a universal understanding of beauty, which is closely related to the experience of positive emotions. However, other cross-cultural studies have reported culture-dependent differences in emotion processing (Tanaka et al., 2010), the level of arousal and valence (Huang et al., 2015), and affective reactions (Grossmann et al., 2012). These research differences indicate the need for further investigation of culture-dependent differences in affective and cognitive processing involved in the judgement of beauty.

Limitations and future directions

Our findings offer valuable insights into cross-cultural aspects of empirical aesthetics. At the same time, some limitations and possible avenues for future research need to be mentioned. First, for the classification of our participants into an individualistic or collectivistic culture, we did not conduct our own measurements but relied on the work of other researchers who have repeatedly shown these cultural differences. Although cultural differences, especially between groups of the younger generation, maybe diminishing in our globalised world (e.g., Ladhari et al., 2015; Taras et al., 2012), also due to Internet usage (e.g., Gaitán-Aguilar et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2009), research, such as the one we present here, proves their existence. Nevertheless, we must point out the general criticism of the dichotomy of cultural dimensions (see e.g., Hong and Chiu, 2001; Hung and Lane, 2016; Mercier, 2011) and refer to suggestions of more dynamic approaches to culture (e.g., Erez and Gati, 2004; Kitayama, 2002; Signorini et al., 2009).

A second limitation is that our study, like many others, was conducted online and mainly involved university students. In order to achieve more ecological validity, it would be desirable to conduct further studies, for example in museums and/or with a more heterogeneous group of visitors. This could lead to more generalisable results, which are particularly important in cross-cultural studies.

Finally, due to the difficulty of power analyses for linear mixed models, we determined our sample size based on a previous study with a similar experimental design. The fact that we were able to replicate our findings across two experiments, suggests that the power of our tests was sufficient to detect these effects. However, future studies may perform simulation-based power analyses using information from our data (Kumle et al., 2021).

Conclusion

In summary, our findings do not support the idea that aesthetic preferences are dependent on culture. Instead, we provide evidence for a universal human beauty response mechanism (Redies, 2015), which is influenced by the stimulus (Berlyne, 1971) and, importantly, tied to positive emotions (Armstrong and Detweiler-Bedell, 2008; Brielmann and Pelli, 2017, 2019; Vartanian and Goel, 2004). As we can see, positive emotional valuation is related to the formation of beauty judgements and intra- and inter-cultural beauty inferences. On the other hand, the relationship between cognitive judgements and beauty judgements and beauty inferences appears to be more specific to groups or cultures (see Miller and Hübner, 2023). As an important new finding, we demonstrated that aesthetic inference abilities exist within and across two distinct cultures. This suggests that aesthetic inference is likely a universal characteristic of the human mind (Brown, 2004). This supports our idea that individuals possess a universal Theory of Aesthetic Preferences (uTAP), which is expected to be based on general human perception and valuation mechanisms (Che et al., 2018; Redies, 2015). It is reasonable to assume that the uTAP is closely related to the general Theory of Mind abilities (Bradford et al., 2018; Shahaeian et al., 2011). It enables individuals to infer the aesthetic preferences of others not only within their own culture, through repeated social interaction and cultural learning (Tomasello et al., 1993), but also across cultures, even in the absence of social interaction, likely due to a universal understanding of beauty (Redies, 2015). These findings are particularly important in the context of inter-cultural interaction, whether in personal or professional settings. We believe that successful aesthetic inference can promote positive collaboration among people around the world.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Armstrong T, Detweiler-Bedell B (2008) Beauty as an emotion: the exhilarating prospect of mastering a challenging world. Rev Gen Psychol 12(4):305–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012558

Aslam MM (2006) Are you selling the right color? A cross‐cultural review of color as a marketing cue. J Mark Commun 12(1):15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527260500247827

Arnheim R (1954) Art and visual perception: a psychology of the creative eye. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Arnheim R (1983) The power of the center: a study of composition in the visual arts. University of California Press, Berkeley

Aubert M, Lebe R, Oktaviana AA, Tang M, Burhan B, Hamrullah et al. (2019) Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art. Nature 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y

Bao Y, Yang T, Lin X, Fang Y, Wang Y, Pöppel E, Lei Q (2016) Aesthetic preferences for eastern and western traditional visual art: identity matters. Front Psychol 7(2143):128–128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01596

Barton, K (2020) Mu-MIn: Multi-model inference. R Package Version 1.43.17. http://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/mumin/

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Berlyne DE (1971) Aesthetics and psychobiology. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York

Birkhoff GD (1933) Aesthetic measure. Harvard University Press

Bland JM, Altman DG (1997) Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 314:572. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

Bode C, Helmy M, Bertamini M (2017) A cross-cultural comparison for preference for symmetry: comparing British and Egyptian non-experts. Psihologija 50:383–402

Bradford EE, Jentzsch I, Gomez J-C, Chen Y, Zhang D, Su Y (2018) Cross-cultural differences in adult theory of mind abilities: a comparison of native-English speakers and native-Chinese speakers on the self/other differentiation task. Q J Exp Psychol 71(12):2665–2676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021818757170

Braun DI, Doerschner K (2019) Kandinsky or Me? How free is the eye of the beholder in abstract art? I-Perception. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041669519867973

Brielmann AA, Pelli DG (2017) Beauty requires thought. Curr Biol 27(10):1506–1513.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.018. ISSN 0960-9822

Brielmann AA, Pelli DG (2019) Intense beauty requires intense pleasure. Front Psychol 10:305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02420

Brown DE (2004) Human universals, human nature & human culture. MIT Press, 133(4). 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526042365645

Cela-Conde CJ, Agnati L, Huston JP, Mora F, Nadal M (2011) The neural foundations of aesthetic appreciation. Prog Neurobiol 94(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.003

Chatterjee A, Widick P, Sternschein R, Smith II WB, Bromberger B (2010) The assessment of art attributes. Empir Stud Arts 28(2):207–222. https://doi.org/10.2190/EM.28.2.f

Che J, Sun X, Gallardo V, Nadal M (2018) Ch. 5—Cross-cultural empirical aesthetics, progress in brain research. vol 237. Elsevier. pp. 77-103, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.002

Chen Z, Xu B, Devereux B (2016) Assessing public aesthetic preferences towards some urban landscape patterns: the case study of two different geographic groups. Environ Monit Assess 188:4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-015-5007-3

Child I, Siroto L (1965) BaKwele and American Esthetic Evaluations Compared. Ethnology 4(4):349–360. https://doi.org/10.2307/3772785

Cutting JE (2003) Gustave Caillebotte French Impressionism, and mere exposure. Psychonomic Bull Rev 10:319–343. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196493

Darda KM, Cross ES (2022) The role of expertise and culture in visual art appreciation. Sci Rep. 12:10666. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14128-7

Dissanayake E (1980) Art as a human behavior: toward an ethological view of art. J Aesthet Art Criticism 38(4):397–406. https://doi.org/10.2307/430321

Dutton D (2005) Aesthetic universals. In: Gaut B & Lopes DM (eds.). The Routledge companion to aesthetics. Routledge, New York, NY. pp. 279–291

Enders CK, Tofighi D (2007) Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol Methods 12(2):121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Erez M, Gati E (2004) A dynamic, multi‐level model of culture: from the micro level of the individual to the macro level of a global culture. Appl Psychol 53(4):583–598

Eysenck HJ, Iwawaki S (1971) Cultural relativity in aesthetic judgments: an empirical study. Percep Mot Skills 32:817–818

Eysenck HJ, Götz KO, Long HY, Nias DKB, Ross M (1984) A new Visual Aesthetic Sensitivity Test—IV. Cross-cultural comparisons between a Chinese sample from Singapore and an English sample. Personal Individ Differ 5,(5):599–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(84)90036-9. ISSN 0191-8869

Farley F, Ahn S-H (1973) Experimental aesthetics: visual aesthetic preference in five cultures. Stud Art Educ 15:44–48

Fechner GT (1876) Vorschule der aesthetik (vol. 1). Breitkopf & Härtel

Gaitán-Aguilar L, Hofhuis J, Bierwiaczonek K, Carmona C (2022) Social media use, social identification and cross-cultural adaptation of international students: a longitudinal examination. Front Psychol 13:1013375

Graf LK, Landwehr JR (2015) A dual-process perspective on fluency-based aesthetics: The pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 19(4):395–410

Graf LK, Landwehr JR (2017) Aesthetic pleasure versus aesthetic interest: the two routes to aesthetic liking. Front Psychol 8:15

Greiner B (2015) Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. J Econ Sci Assoc 1:114–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-015-0004-4

Grossmann I, Ellsworth PC, Hong Y-y (2012) Culture, attention, and emotion. J Exp Psychol: Gen 141(1):31–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023817

Gómez-Puerto G, Rosselló J, Corradi G, Acedo-Carmona C, Munar E, Nadal M (2018) Preference for curved contours across cultures. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 12(4):432–439. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000135

Hager M, Hagemann D, Danner D, Schankin A (2012) Assessing aesthetic appreciation of visual artworks—The construction of the Art Reception Survey (ARS). Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 6(4):320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028776

Han S, Northoff G (2008) Culture-sensitive neural substrates of human cognition: a transcultural neuroimaging approach. Nat Rev Neurosci 9(8):646–654

Hanquinet L, Roose H, Savage M (2014) The eyes of the beholder: aesthetic preferences and the remaking of cultural capital. Sociology 48(1):111–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513477935

Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Peng K, Greenholtz J (2002) What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference-group effect. J Personal Soc Psychol 82(6):903–918. 10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.903

Hoffmann DL, Angelucci DE, Villaverde V, Zapata J, Zilhão J (2018) Symbolic use of marine shells and mineral pigments by Iberian Neandertals 115,000 years ago. Sci Adv 4(2):eaar5255. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar5255

Hofstede G (2011) Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hong YY, Chiu CY (2001) Toward a paradigm shift: From cross-cultural differences in social cognition to social-cognitive mediation of cultural differences. Soc Cogn 19(3): Special issue):181–196. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.19.3.181.21471

Huang J, Xu D, Peterson BS (2015) Affective reactions differ between Chinese and American healthy young adults: a cross-cultural study using the international affective picture system. BMC Psychiatry 15:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0442-9

Hübner R, Fillinger MG (2016) Comparison of objective measures for predicting perceptual balance and visual aesthetic preference. Front Psychol 7:335

Hübner R, Fillinger MG (2019) Perceptual balance, stability, and aesthetic appreciation: their relations depend on the picture type. I-Perception 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2041669519856040

Hung TW, Lane TJ (eds.) (2016) Rationality: constraints and contexts. Academic Press

Hurlbert AC, Ling Y (2007) Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Curr Biol 17(16):R623–R625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.022. ISSN 0960-9822

Iigaya K, Yi S, Wahle IA, Tanwisuth K, O’Doherty JP (2021) Aesthetic preference for art can be predicted from a mixture of low- and high-level visual features. Nat Hum Behav 5:743–755. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01124-6

Iwawaki S, Eysenck HJ, Götz KO (1979) A new visual aesthetic sensitivity test (VAST): II. Cross-cultural comparison between England and Japan. Percept Mot Skills 49(3):859–862. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1979.49.3.859

Ji L-J, Lee A, Guo T (2012) The thinking styles of Chinese people. Oxford University Press

Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A (1982) Judgment under uncertainty. Cambridge University Press

Kimbrough EO, Robalino N, Robson AJ (2017) Applying “theory of mind”: Theory and experiments. Games Econ Behav 106:209–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2017.10.008. ISSN 0899-8256

Kitayama S (2002) Culture and basic psychological processes–toward a system view of culture: Comment on Oyserman et al. Psychol Bull 128(1):89–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.89

Kumle L, Võ MLH, Draschkow D (2021) Estimating power in (generalized) linear mixed models: An open introduction and tutorial in R. Behav Res Methods 53(6):2528–2543. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01546-0

Ladhari R, Souiden N, Choi Y-H (2015) Culture change and globalization: the unresolved debate between cross-national and cross-cultural classifications. Australas Mark J 23(3):235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2015.06.003

LoBue V, DeLoache JS (2011) Pretty in pink: The early development of gender-stereotyped colour preferences. Br J Dev Psychol 29:656–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02027.x

Leder H, Nadal M (2014) Ten years of a model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgements: the aesthetic episode—developments and challenges in empirical aesthetics. Br J Psychol 105(4):443–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12084

Leder H, Belke B, Oeberst A (2004) A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. Br J Psychol 95(4):489–508. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369811

Liu Z, Zheng XS, Wu M, Dong R, Peng K (2013) Culture influence on aesthetic perception of Chinese and western paintings. Presented at the the 6th International Symposium, New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. p. 72

Locher P, Krupinski EA, Mello-Thoms C, Nodine CF (2008) Visual interest in pictorial art during an aesthetic experience. Spat Vis 21(1):55

Madden TJ, Hewett K, Roth MS (2000) Managing images in different cultures: a cross-national study of color meanings and preferences. Journal of International J Int Market 8:4

Marković S (2012) Components of aesthetic experience: aesthetic fascination, aesthetic appraisal, and aesthetic emotion. i-Percept 3(1):1–17

Masuda T, Gonzalez R, Kwan L, Nisbett RE (2008) Culture and aesthetic preference: comparing the attention to context of East Asians and Americans. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 34(9):1260–1275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208320555

Matsumoto D, Nezlek JB, Koopmann B (2007) Evidence for universality in phenomenological emotion response system coherence. Emotion 7(1):57–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.57

Matsumoto DE (2009) The Cambridge dictionary of psychology. Cambridge University Press

Mercier H (2011) On the universality of argumentative reasoning. J Cogn Cult 11(1-2):85–113. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853711X568707

Miller CA, Hübner R (2020) Two routes to aesthetic preference, one route to aesthetic inference. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 14(2):237–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000241

Miller CA, Hübner R (2023) The relations of empathy and gender to aesthetic response and aesthetic inference of visual artworks. Empir Stud Arts 41(1):188–215

Minkov M, Kaasa A (2022) Do dimensions of culture exist objectively? A validation of the revised Minkov-Hofstede model of culture with World Values Survey items and scores for 102 countries. J Int Manag 28(4):100971

Miyamoto Y, Nisbett RE, Masuda T (2006) Culture and the physical environment: Holistic versus analytic perceptual affordances. Psychol Sci 17(2):113–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01673.x

Norenzayan A, Smith EE, Kim BJ, Nisbett RE (2002) Cultural preferences for formal versus intuitive reasoning. Cogn Sci 26:653–684. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2605_4

Norenzayan A, Incheol C, Kaiping P (2007) Perception and cognition. in: Kitayama S, Cohen D (eds.). Handbook of cultural psychology. Guilford Press

Nadal M, Chatterjee A (2018) Neuroaesthetics and art’s diversity and universality. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 10(3):e1487. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1487. Epub 2018 Nov 28. PMID: 30485700

Nisbett RE (2003) The geography of thought: How Asian and Westerners think differently ...and why. Free Press

Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, Norenzayan A (2001) Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol Rev 108(2):291–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291

Nisbett RE, Masuda T (2003) Culture and point of view. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:19. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934527100

Nisbett ER, Peng K, Choi I, Norenzayan A (2008) in: Adler JE, Rips LJ. Reasoning: studies of human inference and its foundations. Cambridge University Press

Ong DC, Zaki J, Goodman ND (2015) Affective cognition: Exploring lay theories of emotion. Cognition 143:141–162

Osborne H (1986) Symmetry as an aesthetic factor. Comput Math Appl 12(1–2):77–82

Ou L-C, Luo MR, Woodcock A, Wright A (2004) A study of color emotion and color preference. Part I: Color emotions for single colors. Color Res Appl 29:232–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.20010

Ou LC, Luo MR, Sun PL, Hu NC, Chen HS (2012) Age effects on colour emotion, preference, and harmony. Color Res Appl 37(2):92–105

Park Y, Guerin DA (2002) Meaning and preference of interior color palettes among four cultures. J Inter Des 28(1):27–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1668.2002.tb00370.x