Abstract

Existing workplace incivility research from the perspective of third parties has been found to be limited in explaining the specific boundary conditions of their constructive responses, such as punishing the instigator and helping the target. The lack of relevant knowledge hinders a comprehensive understanding of the coping strategies favoured by third parties. Building on the deontic model and the value protection model, this research involved two sub-studies with a total of 710 Chinese employees, employing a scenario experiment (Study 1) and a time-lagged survey (Study 2). The results showed that witnessed incivility positively predicted third parties’ workplace ostracism against the instigator, with moral anger acting as a mediator. The research did not identify a direct link between witnessed incivility and third parties’ organisational citizenship behaviour towards the target. However, the mediating role of moral anger between these two variables was found in Study 1. Moreover, Study 1 indicated that political skill strengthened the relationship between witnessed incivility and moral anger, but weakened the relationship between moral anger and third parties’ workplace ostracism against the instigator or their helping behaviour towards the target—findings partially supported by Study 2. These insights provide a practical and theoretical understanding of how organisations can utilise the role of third parties to intervene in workplace incivility effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Workplace incivility refers to low-intensity deviant behaviours that violate social norms for mutual respect but lack a clear intention to harm (Andersson and Pearson 1999, p. 457). Currently, workplace incivility is believed to be more prevalent than other forms of mistreatment (Dhanani et al. 2021), and, as such, it may have detrimental implications for both employees and organisations (e.g., Cortina et al. 2022; Han et al. 2022; Mehmood et al. 2024). Research into incivility has traditionally centred on the direct individuals involved, namely instigators and targets (i.e., victims of mistreatment), whereas the influence of such mistreatment on third parties who witness these incidents has received relatively less attention (Miner et al. 2018; Schilpzand et al. 2016). Researchers have highlighted the importance of investigating third-party intervention in witnessed mistreatment, such as incivility, for a more complete picture of the field (Hill et al. 2025; Ni et al. 2024). The present research resonates with this call by examining third parties’ constructive responses to witnessed incivility—in particular, advocating for the victim by seeking punishment for the instigator or offering social support to the target (e.g., Jensen and Raver 2021; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). This perspective is more consistent with the innate human tendency to support victims rather than ignore the situation or side with instigators (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). In addition, third parties are often numerous (Dhanani et al. 2021). Their timely responses to workplace mistreatment can effectively curb the rapid spread of harmful behaviours, thereby contributing to a healthy work environment (Arman 2020; Ni et al. 2024).

Despite existing studies providing evidence that third parties may react constructively to witnessed incivility (e.g., Jensen and Raver 2021; Lin and Loi 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015), several knowledge gaps remain in this field. First, Hershcovis et al. (2017) have called for an expansion of the range of third-party deontic reactions to witnessed incivility. For example, attention should be given to more specific means of punishment beyond committing the same mistreatment as the instigator based on the principle of an eye for an eye (Lin and Loi 2021). In this regard, ostracising the instigator becomes a tool available to third parties. Research has proposed workplace ostracism as a covert form of retribution against unpopular team members, which may go unnoticed by those being ostracised (O’Reilly 2013; Robinson et al. 2013). Recent findings have also indicated that employees, acting as third parties, proactively exclude peers who are rude to customers (Ni et al. 2024). Considering the prevailing maxim that “the customer is always right”, third-party employees might exhibit amplified moral responses when customers are victims. Thus, it is essential to examine whether third parties view workplace ostracism as a means of punishment when both the instigator and the victim of incivility are internal members of the organisation.

Second, research on the moral agency of third parties, drawing on the deontic model (Folger 2001) and the value protection model (Skitka 2002), suggests that individuals confronted with morally violating situations, such as workplace mistreatment, experience moral anger—a transient state characterised by interconnected emotions like hostility and contempt. This emotional response prompts them to act constructively as a demonstration of their moral character (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011; Priesemuth 2013). Although moral anger is often linked to punitive action against instigators, its mediating role between witnessed workplace mistreatment and assistance behaviour remains unclear. Importantly, while most research has predominantly centred on sympathy as a predictor of third-party prosocial behaviour towards the victim (e.g., Hershcovis and Bhatnagar 2017; Hill et al. 2025), some theoretical models (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011) and empirical evidence (e.g., Mitchell et al. 2015; Reich and Hershcovis 2015) still imply that moral anger may also motivate assistance to targets of mistreatment. Therefore, a more robust evidence base is required to elucidate the role of moral anger in prompting varying constructive responses from third parties.

Third, since the introduction of the deontic model to explain third-party intervention in witnessed workplace mistreatment, researchers have progressively explored the boundary conditions of deontic effects (e.g., Mitchell et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2021; O’Reilly et al. 2016). Emerging research underscores the necessity for a comprehensive examination of whether deontic forces function across the different stages of this process (Lin and Loi 2021; Priesemuth and Schminke 2019). To extend this line of inquiry, it is imperative for scholars to pinpoint the factors that heighten third parties’ sensitivity to situations of injustice (e.g., workplace incivility), thereby eliciting their deontic emotions (Lin and Loi 2021). Current research mostly delineates the boundary conditions that diminish third-party moral anger, such as third parties’ exclusion beliefs about the targeted coworker (Mitchell et al. 2015) and the dark triad (Liu et al. 2021). In exploring strategies to enhance third parties’ moral emotions, scholars have predominantly emphasised the role of moral identity (e.g., Lin and Loi 2021; O’Reilly et al. 2016; Skarlicki and Rupp 2010), yet have stopped short of identifying additional factors that influence the relationship between witnessed incivility and moral anger.

Last, another important focus of research on the boundary conditions of third parties’ moral responses is the examination of the factors that influence the coping strategies they ultimately adopt (i.e., how moral anger translates into their behavioural responses; Lin and Loi 2021; Priesemuth and Schminke 2019). Some research has shown that third parties are more likely to choose punishment for the instigator when intervening in workplace mistreatment (e.g., Reich and Hershcovis 2015; van Prooijen 2010). Conversely, other studies have suggested that victim assistance is often favoured as the primary strategy (e.g., Dhaliwal et al. 2021; Artavia-Mora et al. 2017). The current issue remains underexplored, with a limited number of studies endeavouring to offer initial understanding by investigating the moderating influence of moral identity (Lin and Loi 2021; Mitchell et al. 2015).

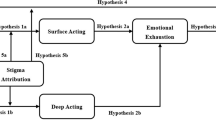

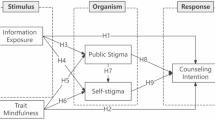

To fill these research gaps, we evaluated our proposed model (shown in Fig. 1) across two studies using a multi-method approach to robustly confirm the reliability of our findings. Grounded in the deontic model and the value protection model, we argue that moral anger mediates the relationship between witnessed incivility and third parties’ workplace ostracism against the instigator (i.e., instigator-oriented punishment) or individually directed organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB-I) towards the target (i.e., target-oriented assistance). To clarify the factors shaping the deontic reactions of third parties, we propose political skill as a boundary condition for these effects. Given its role in keenly perceiving cues in the environment (Frieder et al. 2019; Munyon et al. 2015), political skill can enhance perceptions of unfair situations (e.g., workplace incivility). Additionally, this trait enables individuals to flexibly choose intervention strategies based on practical needs, effectively addressing unforeseen incidents in the workplace (Frieder et al. 2019; Munyon et al. 2015). We thus consider the dual functions of political skill in different stages of third-party reactions (i.e., the former in the deontic emotional reaction and the latter in behavioural reaction; Lin and Loi 2021)—thereby simultaneously examining its moderating role in both stages.

Our work makes several primary contributions. First, our research extends the literature on witnessed workplace mistreatment by revealing that workplace ostracism can be a strategic tool for third parties to penalise those who instigate incivility. This finding supports perspectives that organisational members will distance themselves from deviants within the organisation (O’Reilly 2013; Robinson et al. 2013) and answers recent calls for actively exploring the potential connections between various forms of workplace mistreatment, rather than viewing them in isolation (Cortina et al. 2017; Ferris et al. 2017; Zhan and Yan 2021). Second, our research contributes to the understanding of how moral anger prompts third parties’ responses to workplace mistreatment, especially among Chinese employees. By examining how moral anger elicits distinct constructive responses from third parties towards mistreated individuals, we evaluate the explanatory power of deontic theory in the Eastern workplace context. Last, our research broadens the scope of conditions influencing third-party moral reactions to workplace mistreatment. Unlike the usual emphasis on moral-related variables (e.g., Lin and Loi 2021; Mitchell et al. 2015), we investigate the role of political skill, an individual variable closely associated with organisational ecology, across different stages of the deontic process. This not only identifies sources of influence that can facilitate third-party intervention against incivility but also contributes to this ongoing debate surrounding “punishment or assistance primacy”.

Theoretical framework

The deontic model

Research is increasingly focusing on the role of third parties in workplace mistreatment, with the deontic model providing a key framework (Hill et al. 2025). This model conceptualises appropriate treatment as a moral imperative, inherently viewed as “the right thing to do” (Folger and Stein 2017). Therefore, witnessing workplace mistreatment elicits a sense of moral anger that can motivate retaliation against the instigator (Dhanani and LaPalme 2019; Hill et al. 2025). This concurs with research indicating that observed incivility is related to increased anger and antisocial behaviours directed at the instigator (e.g., Reich and Hershcovis 2015; Lin and Loi 2021; Ni et al. 2024). It is important to emphasise that, although the deontic theory is noted for its perpetrator-focused and anger-focused propositions (e.g., Hill et al. 2025), some researchers have argued that moral anger triggered by witnessed workplace mistreatment can also motivate individuals to engage in victim-focused assistance (e.g., Mitchell et al. 2015; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). This is consistent with the notion that both retributive and supportive responses are morally grounded and contribute to the preservation of the moral order (O’Reilly 2013; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011).

The value protection model

The value protection model (VPM) extends the deontic model’s understanding of third parties’ constructive responses in workplace mistreatment. The VPM highlights the importance of personal identity, particularly the need to maintain a positive personal identity (Skitka 2002). Given that moral values are integral to personal identity, observing workplace mistreatment, including incivility, poses a threat to the observer’s personal identity (Priesemuth 2013). Consequently, third parties may experience moral anger and resort to moral cleansing behaviours, such as penalising the instigator and offering support to the victim, in an effort to strengthen their beliefs in their moral integrity (i.e., their sense of being a good person; Skitka 2002; Skitka and Mullen 2002). Therefore, the VPM supports the deontic model’s premise that observers are driven by moral anger to make deontic responses to the witnessed mistreatment.

In addition to maintaining private personal identity, the VPM suggests that third-party constructive responses to workplace mistreatment serve another important function: contributing to the preservation of public personal identity by demonstrating moral stances to others (Semmer et al. 2019; Skitka 2002). This underscores the potential instrumental benefits of such actions, such as receiving gratitude from peers and thus gaining an improved reputation (Dhaliwal et al. 2021; Jordan and Rand 2020). These benefits help mitigate the limitations of the deontic model—which primarily emphasises purely altruistic motivations behind third parties’ constructive intervention. The VPM acknowledges that individuals may naturally engage in a “cost-benefit mental calculus” once they are aware that a situation might necessitate their involvement (Jensen and Raver 2021, p.886). This analysis can inform the selection of intervention strategies (Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Consequently, the VPM provides a complementary perspective to the deontic model by explaining how third parties might strategically select intervention methods to maximise potential benefits, including improving their public image and reputation.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Witnessed workplace incivility and third parties’ workplace ostracism against the instigator

Workplace ostracism is formally defined as “the extent to which an individual perceives that he or she is ignored or excluded by others” (Ferris et al. 2008, p.1348). Previous studies have shown that third parties often rectify witnessed incivility by seeking punishment for instigators (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011; Reich et al. 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). Inspired by these results, our research provides evidence that workplace ostracism may serve as a form of instigator-oriented punishment.

Evidence supporting this hypothesis can be found in Robinson et al. (2013) model, which demonstrates how organisational members employ “the silent treatment” as a well-known method of “purposeful ostracism” directed at deviant individuals to protect themselves and their teams. Similarly, O’Reilly (2013) proposes that third parties resort to “covert social sanctions” to impose a social cost on instigators of workplace mistreatment. Workplace ostracism, a form of such social sanctioning, is largely effective because it precludes instigators from capitalising on the benefits derived from their social networks (O’Reilly 2013). For example, third parties are hesitant to engage in future collaborations with individuals who exhibit incivility (Reich and Hershcovis 2015), thereby eroding the instigator’s reputation and social relationships, which in turn lead to an unintended social cost (Guo et al. 2021; O’Reilly 2013).

In spite of the widespread belief that third parties would ostracise the instigator of incivility (e.g., Ferris et al. 2017; Zhan and Yan 2021), empirical evidence in this area remains limited. Recent research indicates that third parties ostracise those who instigate incivility against customers (Ni et al. 2024), but this reaction appears to be influenced by the role of the victim as a customer. In this research, we examine whether third parties use such punishment in response to incivility between coworkers, a more prevalent and subtle violation of workplace interpersonal norms (Lin and Loi 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). Thus, we hypothesise as follows:

Hypothesis 1. Witnessed workplace incivility is positively related to workplace ostracism against the instigator.

Witnessed workplace incivility and third parties’ individually directed organisational citizenship behaviour towards the target

Third parties’ punishment against instigators has garnered substantial scholarly interest, but the potential of another constructive intervention—helping the target—cannot be ignored. It is worth recognising that both punishing the wrongdoer and aiding the victim are considered constructive responses, as they can restore a sense of justice threatened by moral violations stemming from witnessed workplace mistreatment (O’Reilly 2013; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). Furthermore, both forms of intervention can serve as means of “moral cleansing” that help third parties maintain their self-identity (Priesemuth 2013).

Previous research has provided evidence supporting this hypothesis. For instance, when third parties observe abusive supervision (Arman 2020; Priesemuth 2013), workplace incivility (Chui and Dietz 2014; Jensen and Raver 2021; Reich et al. 2021), workplace bullying (Coyne et al. 2019), or other forms of workplace mistreatment, they exhibit varying degrees of willingness to help the victim. Even with this abundant evidence, it is important to note that some studies have not clearly specified the manifestation of helping behaviours, leading to discrepancies in measurement (e.g., Chui and Dietz 2014). In this research, we employ the concept of “individually directed organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB-I)” introduced by Aryee et al. (2002) to assess the extent to which third parties offer assistance to targets of workplace incivility. This behaviour involves individuals actively providing aid without being constrained by organisational role requirements, thereby demonstrating their moral motivations (Bowes-Sperry and O’Leary-Kelly 2005). Given the above arguments, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2. Witnessed workplace incivility is positively related to OCB-I towards the target.

The mediating role of moral anger

The existing decision-making process models for third-party intervention in workplace mistreatment are mostly cognitive-oriented, assuming that third parties will decide on the intervention behaviours following a comprehensive evaluation of the incident (e.g., Bowes-Sperry and O’Leary-Kelly 2005; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). The deontic model presents an alternative view, stating that the decision-making process for third-party intervention is not always rational or controllable. More often, it is merely a rapid instinctive response to unfair events driven by emotion, rather than a careful consideration of the benefits and risks associated with their behaviours (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). Therefore, our research’s initial concern is examining the emotion-driven pathway of third-party intervention in workplace incivility, suggesting that the emotion aroused by unfair events can facilitate the initial motivation for individual intervention.

According to the deontic model, when witnessing workplace mistreatment, third parties are inclined to develop implicit moral intuitions that perceive the ethical impropriety and violations of such treatment. Simultaneously, such intuitions can elicit moral anger, a negative affective state encompassing various discrete emotions such as anger, hostility, and contempt (Hill et al. 2025). Consequently, this emotional response may spur observers to stop the mistreatment (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). The VPM also presents similar opinions, suggesting that moral anger motivates third parties to respond to workplace mistreatment to protect personal moral values (Priesemuth 2013). Notably, although previous research has established a strong association between anger and punitive behaviours (Hill et al. 2025; Jordan and Rand 2020; Reich and Hershcovis 2015), some researchers have also highlighted that moral anger can drive individuals to assist victims (Mitchell et al. 2015), because both responses can be viewed as deontic reactions that play crucial roles in relieving third parties’ anger and facilitating their own sense of justice restoration (O’Reilly 2013; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a. Moral anger mediates the relationship between witnessed workplace incivility and workplace ostracism against the instigator.

Hypothesis 3b. Moral anger mediates the relationship between witnessed workplace incivility and OCB-I towards the target.

Intervention preference in workplace incivility: moral and self-interest motivations

While both punishment and assistance can restore a sense of justice after fairness norms have been violated, individuals may prefer different coping strategies: Some scholars suggest that punishing instigators is the most direct and effective way to make them face consequences (van Prooijen 2010). Moral anger is associated with instigator-focused attention, which often leads to the neglect of victims (Gummerum et al. 2016; Hill et al. 2025; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). This punitive tendency is also socially grounded: Instigators are generally considered threatening to society, and it aligns with third parties’ instinctive desire to punish them (van Prooijen 2010). However, the potential risks of harsh punishment may render these actions counterproductive. If third parties face the risk of retaliation (Artavia-Mora et al. 2017), or struggle with assigning clear responsibility for the observed mistreatment (Skarlicki and Kulik 2005), blindly implementing punishment may result in unfavourable outcomes. Additionally, helping behaviour, in contrast to punitive action that may deviate from moral values themselves (Lin and Loi 2021), better demonstrates altruism and becomes the superior strategy for third-party intervention (Dhaliwal et al. 2021; Jordan and Rand 2020).

The debate points out the limitations of the intuitive perspective: while moral anger can explain individuals’ initial moral motivations for intervention (O’Reilly and Aquino 2011), it falls short in explaining the variations in intervention methods among individuals. In fact, the deontic model does not exclude the instrumental motivations of third parties, and the decision-making process of intervention incorporates rational processing (Dhanani and LaPalme 2019; Folger and Stein 2017). When individuals strive to identify the most optimal constructive response, they often conduct cost-benefit analyses (Bowes-Sperry and O’Leary-Kelly 2005; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Recent research by Jensen and Raver (2021) challenges the notion of a complete separation of moral motivations and self-interest motivations in individual intervention against workplace incivility. Based on these findings, it is suggested that preference differences in third-party intervention strategies arise from the combined influence of both motives.

Self-interest motivations in third-party intervention: a VPM-based perspective

Third-party intervention in workplace mistreatment involves both an intrapsychic process, which concerns moral motives and moral anger arising from unfair incidents (i.e., the deontic emotional reaction), and an interpersonal behaviour process, where third parties consciously or unconsciously weigh the costs and benefits to choose the most effective strategy to exert influence through these actions (i.e., the behavioural reaction; Bowes-Sperry and O’Leary-Kelly 2005; Lin and Loi 2021; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Building on the VPM and extending the perspective of the deontic model, we propose that third parties are instinctively driven to make constructive responses to workplace mistreatment in order to uphold moral principles. Such actions not only reinforce their positive self-evaluations but also communicate the moral stances of these individuals to others, leading to positive external evaluations and ultimately enhancing the reputation of these actors (Skitka 2002; Skitka and Mullen 2002). Even though self-interest motives might not constitute the initial impetus of third parties’ constructive responses, individuals’ morally driven actions can contribute to personal benefit, irrespective of their awareness (Jensen and Raver 2021; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005).

The moderating role of political skill

This research considers the functions of political skill in different stages of third-party reactions (i.e., the former in the intrapsychic process and the latter in the interpersonal behaviour process) and simultaneously examines its moderating role in both stages. Individuals with high political skill possess social astuteness, enabling them to comprehend others’ motives and desires. They also demonstrate interpersonal influence by adapting to and engaging in situationally appropriate behaviours, manifest sincerity through goodwill and trustworthiness, and establish beneficial alliances with key individuals using their networking abilities (Ferris et al. 2007). The influence of political skill extends beyond individuals to affect those around them as well. In other words, political skill is thought to shape not only individuals’ self-assessment and self-image but also the perceptions others have of them (Munyon et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019). This dual capacity aligns with individuals’ motivation to uphold moral values when intervening in incivility. Hence, political skill affects deontic responses of third parties through its moderating effects on both their emotional reactions to witnessed incivility and the relationship between emotional reactions and intervention behaviours.

Intrapsychic process: the influence of political skill on third parties’ emotional reactions

Political skill operates beginning with an individual’s self-assessment and situational assessment in specific contexts, collectively reflecting the intrapsychic effects of political skill (Munyon et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019). Those who possess high political skill are adept at interpreting and navigating the subtleties and complexities of personal motivation and the workplace environment (Ferris et al. 2007), a proficiency essential for evaluating the inherent ambiguity of workplace incivility.

Specifically, political skill influences an individual’s self-assessment of personal resources (Munyon et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019), with those exhibiting high political skill demonstrating an ability to comprehend and influence various aspects and elements of the work environment, thereby fostering a high level of self-efficacy (Munyon et al. 2015). This sense of control within the work environment empowers them to confidently address unforeseen challenges (e.g., witnessed incivility) and sustain the smooth operation of the organisation (Ferris et al. 2007). Moreover, third parties who exhibit stronger motivation for intervention against observed injustice are more likely to report increased levels of moral anger (Jordan and Rand 2020).

Political skill also plays a prominent role in impacting individuals’ evaluation and comprehension of their environment, particularly within the context of interpersonal relationships. Through perspective-taking, political skill empowers individuals to gain a deeper understanding of others’ preferences and needs (Frieder et al. 2019; Munyon et al. 2015). Research has identified a strong relationship between political skill and deep acting, which refers to the ability to regulate emotional expressions in accordance with situational demands while maintaining genuine emotion (Toomey et al. 2021). Therefore, it is postulated that individuals with higher political skill are more likely to exhibit emotions and attitudes congruent with the circumstances they encounter, especially in the face of incivility: They intuitively experience anger towards the instigator and stand in solidarity with the victims (Reich and Hershcovis 2015). This victim-oriented approach elicits a stronger perception of moral transgression, leading to increased levels of moral anger (Fiori et al. 2016; Reich et al. 2021). Based on the above evidence, we predict that:

Hypothesis 4a. Political skill moderates the relationship between witnessed incivility and moral anger, such that the relationship is weaker when political skill is lower rather than higher.

Interpersonal behaviour processes: the influence of political skill on third parties’ behavioural reactions

Following the intrapsychic effects, political skill further influences individuals’ interpersonal behaviour, primarily through prompting them to engage in behaviours that project a positive self-image to influence others’ evaluations (Frieder et al. 2019; Munyon et al. 2015). Individuals with high political skill exhibit a comprehensive comprehension of social interaction rules. This allows them to flexibly adjust their behaviour in diverse situations and with diverse individuals, thereby effectively employing influencing strategies (Ahearn et al. 2004; Ferris et al. 2007; McAllister et al. 2018).

Highly politically skilled individuals place a priority on maintaining interpersonal relationships (Wang and Luan 2024) and are less likely to confront instigators directly (Liu et al. 2008; Wu and Yang 2019). A workplace survey conducted in China revealed that employees with high political skill are tactful in handling matters and strive to maintain professional friendships with a wide range of colleagues (Liu et al. 2008). Even when confronted with witnessed incivility that incites moral anger, these employees refrain from using impulsive and destructive tactics, such as workplace ostracism, which may escalate conflicts and harm their reputation—a concept referred to as “face” in Chinese culture. Conversely, political skill predicts OCBs, enabling third parties to maintain high levels of helpfulness despite unpleasant organisational experiences (Kaur and Kang 2023; Moon and Morais 2022). By engaging in acts of assistance, individuals not only restore their own sense of justice but also cultivate a positive impression among their colleagues, a process that can be seen as a form of impression management (Brouer et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019; McAllister et al. 2018), leading to favourable evaluations. In conclusion, when observing workplace incivility, highly politically skilled individuals are less likely to resort to punitive behaviours rooted in moral anger. Instead, they tend to shift towards offering substantial assistance, safeguarding their own self-value, and sustaining positive social connections. Hence, we predict that:

Hypothesis 4b. Political skill moderates the relationship between moral anger and workplace ostracism against the instigator, such that the relationship is weaker when political skill is higher rather than lower.

Hypothesis 4c. Political skill moderates the relationship between moral anger and OCB-I towards the target, such that the relationship is weaker when political skill is lower rather than higher.

Together, Hypotheses 1-4 suggest a moderated mediation model. The indirect effect of witnessed workplace incivility on OCB-I towards the target through moral anger is lower for third parties with lower political skill. Regarding the indirect relationship between witnessed incivility and third parties’ ostracism against the instigator through moral anger, third parties’ political skill may amplify the first-stage relationship and alleviate the second-stage effect. Therefore, the relative magnitude of the two competing forces will determine the direction of the influence of political skill on this indirect relationship.

Hypothesis 5a (Exploratory). Political skill moderates the positive indirect effect of witnessed workplace incivility on workplace ostracism against the instigator through moral anger.

Hypothesis 5b. Political skill moderates the positive indirect effect of witnessed workplace incivility on OCB-I towards the target through moral anger, such that the indirect effect is weaker when political skill is lower rather than higher.

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedures

A single-factor two-level (condition: civil vs. uncivil) between-subjects design was employed in Study 1. We applied a scenario-simulation approach to manipulate the independent variable (witnessed incivility)—a technique validated in previous research (e.g., Lin and Loi 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015; Reich et al. 2021). We collected examples of civil and uncivil behaviours from established scales (e.g., Chen et al. 2019) and adapted them to the Chinese workplace culture to develop written vignettes depicting civil or uncivil workplace interactions (see Supplementary Appendix A). The scenarios were crafted without specifying the characters’ attributes, such as gender and position, to avoid influencing third-party interpretations (Lin and Loi 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions, and instructed to imagine witnessing the described interaction. They then evaluated their emotional and behavioural reactions and completed the relevant scales. When deciding the anticipated effect size, we referred to Reich and Hershcovis’ (2015) experiment, in which the effect sizes of incivility conditions were small for both punishment against the instigator (η2 = 0.08) and assistance towards the target (η2 = 0.05). Given these considerations, we conducted a priori power analysis in G*Power (Faul et al. 2009), specifying t-tests (difference between two independent means), a small effect size (d = 0.25), and an α of 0.05, which indicated that a minimum of 506 participants was needed to achieve 80% power.

Full-time employees were recruited from a state-owned company in Central China, with the support of the company’s management who encouraged employees to participate. Prior to the survey, we guaranteed participants the confidentiality and voluntary nature of our experiment. Our initial dataset included 562 participants, but we had to exclude 18 who failed to pass an attention check and 6 who had excessively short response times (i.e., <2 min). This left us with a final sample of 538 employees, of whom 60.59% were male. The age distribution was as follows: 31.97% were aged 18–29, 27.14% were aged 30–39, and 40.89% were aged 40 or above. Regarding educational background, 56.13% had high school diplomas or below, 37.17% held bachelor’s degrees, and 6.70% had master’s degrees or higher. In terms of tenure, 31.04% had less than 3 years, 13.75% had 3–5 years, and 55.21% had more than 5 years. The distribution of professional titles was as follows: 71.00% of the participants were at the junior level, 25.28% were at the intermediate level, and 3.72% were at the senior level.

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The measures were translated into participants’ native language using the recommended back-translation procedures (Brislin 1970).

Manipulation check

In order to validate the manipulation, all participants were asked to rate the degree of incivility of each episode on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = no incivility, 5 = extreme incivility).

Moral anger

We used a three-item scale adapted from Raver et al. (2012) to assess participants’ moral anger towards the scenario. An example item is “I feel angry about the scenario.” Cronbach’s α was 0.887. The individual measurement model for moral anger was a saturated model: CFI = 1.000; IFI = 1.000; SRMR = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.000.

Workplace ostracism against the instigator

We adapted Jiang et al. (2011) nine-item scale to measure participants’ proactive exclusion against the instigator within the scenario. This scale is based on the Workplace Ostracism Scale developed by Ferris et al. (2008) and has been adapted to Chinese cultural contexts. An example item is “I avoid the instigator at work.” Cronbach’s α was 0.928. The initial individual measurement model fit was χ2/df = 16.211; CFI = 0.880; IFI = 0.880; SRMR = 0.059; RMSEA = 0.168. Model fit improvement was conducted by correlating error terms based on the modification indices (Collier 2020). All modifications were made in accordance with realistic and theoretically justifiable interpretations. The revised individual measurement model for workplace ostracism against the instigator yielded a good fit for the data: χ2/df = 5.075; CFI = 0.973; IFI = 0.973; SRMR = 0.033; RMSEA = 0.087.

OCB-I towards the target

We used a 4-item scale pooled from the extant literature (e.g., Aryee et al. 2002, 2024; Henderson et al. 2020) to measure participants’ assistance towards the target within the scenario. An example item is “I voluntarily help the target settle into the job.” Cronbach’s α was 0.897. The individual measurement model fit for OCB-I was χ2/df = 11.565; CFI = 0.984; IFI = 0.984; SRMR = 0.020; RMSEA = 0.140. The suboptimal performance of the RMSEA may be ascribed to the small degrees of freedom (Kenny et al. 2015).

Political skill

Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with a six-item measure of political skill (Ahearn et al. 2004). An example item is “I find it easy to envision myself in the position of others.” Cronbach’s α was 0.903. The initial individual measurement model fit was χ2/df = 6.722; CFI = 0.972; IFI = 0.972; SRMR = 0.030; RMSEA = 0.104. Model fit improvement was conducted by correlating error terms based on the modification indices, and the CFA confirmed that the revised unidimensional structure is a good fit for the data: χ2/df = 3.617; CFI = 0.989; IFI = 0.989; SRMR = 0.020; RMSEA = 0.070.

Control variables

Third parties’ socio-demographic variables have been shown to influence their responses to the witnessed workplace mistreatment (Chui and Dietz 2014; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). Therefore, participants’ gender, age, education, tenure, and position were collected and controlled.

Results

Manipulation check

An independent samples t-test was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the incivility manipulation by using incivility condition (uncivil or civil) as the independent variable and participants’ incivility rating of the scenario as the dependent variable. Participants in the uncivil condition (M = 4.74, SD = 0.51) perceived that the instigator behaved more uncivilly towards the target than those in the civil condition (M = 1.36, SD = 0.56), t(491.18) = −72.22, p < 0.001. Hence, we concluded that participants correctly perceived the incivility condition.

Measurement model evaluation

We evaluated construct reliability using composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Table 1 shows that the CR and AVE for all constructs exceed the recommended thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. The factor loadings of the items exceeded 0.5 (Cortina et al. 2001; Ferris et al. 2005). To evaluate the discriminant validity of the study variables (moral anger, workplace ostracism against the instigator, OCB-I, and political skill), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS. A four-factor measurement model provided satisfactory model fit (χ2/df = 4.038; CFI = 0.926; IFI = 0.926; SRMR = 0.044; RMSEA = 0.075). The model fit of the four-factor model was better than that of all the other alternative measurement models, including the three-factor model combining workplace ostracism and OCB-I (χ2/df = 11.430; CFI = 0.741; IFI = 0.741; SRMR = 0.173; RMSEA = 0.139) and the two-factor model combining workplace ostracism, OCB-I and political skill (χ2/df = 19.444; CFI = 0.537; IFI = 0.538; SRMR = 0.216; RMSEA = 0.185). The one-factor model yielded a poor fit (χ2/df = 21.962; CFI = 0.471; IFI = 0.472; SRMR = 0.222; RMSEA = 0.198). Therefore, the study variables are conceptually distinctive.

Hypothesis testing

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for the variables in Study 1. We employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes 2018) to examine conditional indirect effects within moderated mediation models and assessed our hypothesis. We used 5000 bootstrapped samples to calculate the point estimates and bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects.

Mediating effect analysis

We used Model 4 to examine simple mediation. As shown in Table 3, witnessed incivility had a significant positive effect on workplace ostracism against the instigator (β = 1.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.01, 1.34]), supporting Hypothesis 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 3a, moral anger mediated the effect of witnessed incivility on workplace ostracism against the instigator (indirect effect = 0.58, Boot SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.44, 0.72]). Contrary to Hypothesis 2, witnessed incivility had a significant negative effect on OCB-I towards the target (β = −0.55, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.75, −0.36]). Moral anger still mediated the relationship between these two variables (indirect effect = 0.24, Boot SE = 0.09, 95% CI [0.05, 0.40]), thus supporting Hypothesis 3b.

Moderated mediating effect analysis

We employed Model 58 to verify the moderating role of political skill and the validity of the whole moderated mediation model. Consistent with Hypothesis 4a, the interaction between witnessed incivility and political skill on moral anger was significant (β = 0.57, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.40, 0.74]). As shown in Fig. 2, witnessed incivility had a stronger positive effect on moral anger at higher levels of political skill (simple slope = 1.83, p < 0.001) than at lower levels (simple slope = 0.70, p < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 4b, the interaction between moral anger and political skill on workplace ostracism against the instigator was significant (β = −0.11, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.20, −0.03]). The simple slope analysis revealed that moral anger had a stronger positive effect on workplace ostracism against the instigator at lower levels of political skill (simple slope = 0.57, p < 0.001), and the effect diminished when political skill was higher (simple slope = 0.34, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 4c was not supported, as the interaction between moral anger and political skill had a negative effect on OCB-I towards the target (β = −0.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.27, −0.08]). Moral anger had a stronger positive effect on OCB-I towards the target at lower levels of political skill (simple slope = 0.25, p < 0.001) compared to higher levels (simple slope = −0.11, p < 0.05).

a Moderating effect of political skill on the relationship between witnessed incivility and moral anger. b Moderating effect of political skill on the relationship between moral anger and workplace ostracism against the instigator. c Moderating effect of political skill on the relationship between moral anger and OCB-I towards the target. High/low = 1 SD above/below the mean.

We then compared the indirect effects across different levels of political skill. Moral anger played a mediating role between witnessed incivility and workplace ostracism against the instigator at both lower levels (indirect effect = 0.40, Boot SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.25, 0.56]) and higher levels (indirect effect = 0.62, Boot SE = 0.13, 95% CI [0.37, 0.89]) of political skill. The difference between the two effects was not statistically significant (Diff = 0.22, Boot SE = 0.14, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.24]), failing to support Hypothesis 5a. In addition, moral anger played a mediating role between witnessed incivility and OCB-I towards the target at lower levels (indirect effect = 0.18, Boot SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.06, 0.31]) instead of higher levels (indirect effect = −0.21, Boot SE = 0.14, 95% CI [−0.48, 0.08]) of political skill, leading to a statistically significant difference between these two effects (Diff = −0.39, Boot SE = 0.15, 95% CI [−0.67, −0.08]), in support of Hypothesis 5b. Figures 3 and 4 provide a visual representation of the conditional indirect, direct and total effects across different moderator levels.

Study 1 discussion

Study 1 has revealed that moral anger plays a mediating role between witnessed workplace incivility and the subsequent coping strategies, with political skill acting as a moderator in this relationship. However, there are some limitations in Study 1 that prompt us to conduct a second study. First, the evaluation in Study 1 of participants’ responses to fictional uncivil scenarios may suffer from limited ecological validity. Consequently, Study 2 asks participants to recall their actual experiences dealing with real-life uncivil incidents. Second, considering the research trends that explore political skill at the dimensional level (Ferris et al. 2019; Frieder et al. 2019; McAllister et al. 2018), Study 2 aims to explore the moderating effects of the four sub-dimensions of political skill: social astuteness, interpersonal influence, networking ability, and apparent sincerity (Ferris et al. 2005). Despite the lack of existing theoretical knowledge on the distinct mechanisms of these dimensions, conducting exploratory or post-hoc data analyses to replace the omnibus political skill construct with its four specific dimensions in empirical research could enhance understanding in this area (Frieder et al. 2019, p. 559).

Study 2

Sample and procedure

Data were collected from full-time employees of a company in Western China through snowball sampling, with participants completing two online surveys, 1 week apart. This convenience sampling technique has been successfully utilised by researchers studying workplace mistreatment (e.g., Mitchell et al. 2015). Prior to the Time 1 survey, a critical incident technique was employed to ask participants to recall instances of uncivil interactions between two colleagues that they had witnessed at the workplace, involving impolite language, unfriendly attitudes, and offensive gestures, with explicit instructions to exclude intended aggression or physical assaults. Specifically, this technique required participants to recall details (e.g., time, venue, and process) of the witnessed incivility to enhance retrospective accuracy and vividness of their reports (Lin and Loi 2021; Mitchell et al. 2015). Participants provided the initials of the instigator and target in that situation, which were automatically inserted into the Time 1 and Time 2 survey items. For instance, when assessing ostracism towards the instigator, respondents were asked to refer to the situation and individuals identified in the situation they had provided. In addition, the critical incident description provided by the respondents at the beginning of the Time 1 survey was presented to them again at the start of the Time 2 survey for reference. Participants who reported not having directly witnessed incivility were excluded from the analysis.

In the first survey, participants completed measures of witnessed incivility, moral anger, political skill, and demographics. The second survey collected data on third-party responses to the mistreatment, including workplace ostracism against the instigator and OCB-I towards the target. Researchers recommend the use of time separation between predictor and criterion variables to reduce common method variance concerns (Podsakoff et al. 2012). A 1-week separation was employed because shorter intervals are believed to enhance the accuracy of participants’ self-reported information regarding low-intensity behaviours (Meier and Spector 2013).

At Time 1, we initially collected 193 responses, from which 4 were excluded due to insufficient incivility detail, and 2 failed the attention check, yielding 187 valid responses. At Time 2, we received 172 matched responses. Among the participants, 51.16% were male. The age distribution was as follows: 51.74% were aged 18–29, 11.05% were 30–39, 37.21% were aged 40 or above. Regarding educational background, 32.56% had high school diplomas or below, 54.07% held bachelor’s degrees, and 13.37% had master’s degrees or higher. In terms of tenure, 51.16% had less than 3 years, 1.75% had 3–5 years, 47.09% had more than 5 years. The distribution of professional titles was as follows: 72.67% of the participants were at the junior level, 26.16% were at the intermediate level, and 1.17% were at the senior level.

Measures

Unless otherwise noted, items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Witnessed incivility (T1)

We used a 7-item scale adapted from previous research (Cortina et al. 2001). Third parties were asked to rate how often they were aware of the instigator (identified in the critical incident) engaging in each of the listed forms of incivility against the target (e.g., “Put the target down or was condescending to the target”). In Study 2, we deleted one item with low factor loading: “Make unwanted attempts to draw the target into a discussion of personal matters” (factor loading = 0.294). Cronbach’s α was 0.901. The initial individual measurement model fit was χ2/df = 7.787; CFI = 0.904; IFI = 0.905; SRMR = 0.059; RMSEA = 0.199. We adopted the same model refinement strategy as Study 1, confirming a good fit for the data with the revised unidimensional structure: χ²/df = 2.203; CFI = 0.987; IFI = 0.987; SRMR = 0.021; RMSEA = 0.084.

Moral anger (T1)

Same as Study 1. Cronbach’s α was 0.839. The individual measurement model for moral anger was a saturated model: CFI = 1.000; IFI = 1.000; SRMR = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.000.

Workplace ostracism against the instigator (T2)

Same as Study 1. In Study 2, we deleted one item with low factor loading: “When the instigator achieves success at work, I choose not to offer congratulations (factor loading = 0.458)”. Cronbach’s α was 0.892. The revised individual measurement model yielded a good fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.946; CFI = 0.985; IFI = 0.985; SRMR = 0.034; RMSEA = 0.074.

OCB-I towards the target (T2)

Same as Study 1. Cronbach’s α was 0.865. The CFA confirmed that the unidimensional structure is a good fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.222; CFI = 0.999; IFI = 0.999; SRMR = 0.016; RMSEA = 0.036.

Political skill (T1)

Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with an 18-item measure of political skill which defined the four dimensions of political skill: social astuteness (e.g., “I understand people very well”), interpersonal influence (e.g., “I am able to make most people feel comfortable and at ease around me”), networking ability (e.g., “I am good at building relationships with influential people at work”), and apparent sincerity (e.g., “I try to be genuine in what I say and do”) (Ferris et al. 2005). The Cronbach’s α for the total scale was 0.888, with the α values for each factor dimension being 0.767, 0.846, 0.835, and 0.725, respectively. The initial individual measurement model fit was χ2/df = 2.523; CFI = 0.847; IFI = 0.849; SRMR = 0.082; RMSEA = 0.094. The same model refinement strategy was employed, with the revised four-dimensional structure yielding a good fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.891; CFI = 0.912; IFI = 0.912; SRMR = 0.076; RMSEA = 0.072.

Control variables

Participants’ gender, age, education, tenure, and position were included as control variables.

Results

Common method bias check

Harman’s one-factor test was used to explore whether our results were susceptible to common method bias. Common method variance would be considered if an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) produced one factor that accounts for more than 40% of the covariance among the variables. In our case, all factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 collectively accounted for 70.34% of the variance, and the largest retained factor explained 18.73% of the total variance.

Measurement model evaluation

Table 4 shows that the CR and AVE for all constructs exceed the recommended thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. The factor loadings of the items are higher than the threshold of 0.5 (Cortina et al. 2001; Ferris et al. 2005). Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the construct validity of our five measures (witnessed workplace incivility, moral anger, political skill, workplace ostracism and OCB-I). We first loaded items onto their corresponding latent constructs, but the CFA model did not converge, possibly due to the small sample size. It is recommended that the parameter-to-sample size ratio meet or exceed the recommended ratio of 1:5 (Liu et al. 2019). To handle this issue, we parcelled the items of political skill based on dimensions using the internal-consistency approach (Kishton and Widaman 1994). The CFA results showed that the refined 5-factor model fit the data well (χ2/df = 1.889; CFI = 0.906; TLI = 0.907; SRMR = 0.077; RMSEA = 0.072). The model fit of the five-factor model was better than that of all the other alternative measurement models, including the four-factor model combining workplace ostracism and OCB-I (χ2/df = 3.806; CFI = 0.690; IFI = 0.694; SRMR = 0.116; RMSEA = 0.128) and the four-factor model combining moral anger and political skill (χ2/df = 2.990; CFI = 0.625; IFI = 0.629; SRMR = 0.101; RMSEA = 0.108). The one-factor model yielded a poor fit (χ2/df = 6.520; CFI = 0.377; IFI = 0.383; SRMR = 0.159; RMSEA = 0.180). Therefore, the study variables are conceptually distinct.

Hypothesis testing

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the variables in Study 2 are presented in Table 2.

Mediating effect analysis

We used Model 4 to examine simple mediation. As shown in Table 3, witnessed incivility had a significant positive effect on workplace ostracism against the instigator (β = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.40]), supporting Hypothesis 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 3a, moral anger mediated the effect of witnessed incivility on workplace ostracism against the instigator (indirect effect = 0.06, Boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.13]). Neither witnessed incivility (β = 0.06, p = 0.44, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.25]) nor moral anger (β = 0.05, p = 0.60, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.23]) had a significant effect on OCB-I towards the target. Furthermore, the mediating role of moral anger in the relationship between witnessed incivility and OCB-I towards the target was non-significant (indirect effect = 0.01, Boot SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.06]). Consequently, Hypotheses 2 and 3b were not supported. Given that our findings only supported the mediating role of moral anger between witnessed incivility and workplace ostracism against the instigator, we conducted a structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis on this mediating model and enhanced the model fit by correlating error terms as suggested by modification indices (Collier 2020). The results showed the revised model had good fit indicators (χ2/df = 1.979; CFI = 0.941; IFI = 0.942; SRMR = 0.065; RMSEA = 0.076).

Additionally, a post hoc power analysis was conducted using the tool developed by Schoemann et al. (2017) to assess the power in our mediation model. For this purpose, we chose values of 5000 and 20,000 for the total number of power analysis replications and the number of coefficient draws per replication respectively. Furthermore, standardised coefficients were incorporated into the model to ensure methodologically rigorous estimation. The post hoc power analysis revealed that with a sample size of 172, Study 2 achieved a power level of 0.83 at a two-tailed significance level of α = 0.05 for the indirect effect mediated by moral anger.

Moderated mediating effect analysis

We employed Model 58 to examine the moderating role of political skill and the validity of the whole moderated mediation model. Consistent with Hypothesis 4a, the interaction between witnessed incivility and political skill on moral anger was significant (β = 0.12, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.25]). The simple slope analysis revealed that witnessed incivility had a stronger positive effect on moral anger at higher levels of political skill (simple slope = 0.39, p < 0.001) compared to lower levels (simple slope = 0.15, p = 0.10) (see Fig. 5). The interactions between moral anger and political skill on workplace ostracism against the instigator (β = −0.02, p = 0.79, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.08]) and OCB-I towards the target (β = −0.12, p = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.26, −0.01]) were non-significant, providing limited support for Hypotheses 4b and 4c.

We further examined the moderating effects of the four dimensions of political skill. Except for apparent sincerity (β = 0.24, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.38]), the interaction between witnessed incivility and the other three dimensions of political skill (social astuteness: β = 0.04, p = 0.57, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.19]; interpersonal influence: β = 0.13, p = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.27]; networking ability: β = 0.09, p = 0.15, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.22]) on moral anger was non-significant, partially supporting Hypothesis 4a. As shown in Fig. 5, witnessed incivility had a stronger positive effect on moral anger under conditions of higher levels of apparent sincerity (simple slope = 0.54, p < 0.001) than under lower levels (simple slope = 0.05, p = 0.61). Hypothesis 4b was not supported because the interaction between moral anger and each dimension of political skill (social astuteness: β = −0.01, p = 0.81, 95% CI [−0.15, 0.07]; interpersonal influence: β = 0.01, p = 0.90, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.12]; networking ability: β = −0.03, p = 0.56, 95% CI [−0.16, 0.07]; apparent sincerity: β = 0.06, p = 0.30, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.17]) on workplace ostracism against the instigator was non-significant. In addition, the interaction between moral anger and each dimension of political skill (social astuteness: β = −0.04, p = 0.53, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.08]; interpersonal influence: β = −0.14, p = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.27, −0.01]; networking ability: β = −0.08, p = 0.23, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.03]; apparent sincerity: β = −0.12, p = 0.08, 95% CI [−0.24, 0.01]) on OCB-I towards the target was non-significant, failing to support Hypothesis 4c.

Considering the evidence for Hypotheses 3a and 4a, we further examined the validity of the whole moderated mediation model by using Model 7. To account for the moderating effect involving latent variables, interaction terms must be constructed by pairing product indicators in AMOS. However, the variety of strategies for generating these indicators can affect analytical outcomes. Thus, we utilised Mplus to conduct a latent moderated SEM. We developed both a baseline model and an enhanced model incorporating latent moderation terms, and then compared their fit indicators. The baseline model was found to fit well (χ2/df = 1.931; CFI = 0.919; TLI = 0.921; SRMR = 0.075; RMSEA = 0.074). The comparison of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values between the two models revealed a difference of less than 2 (baseline: AIC = 10,627.003; enhanced: AIC = 10,628.980), suggesting no significant superiority of the baseline model over the enhanced model with latent moderation terms (Bevans 2023). Consequently, the SEM with latent moderation from Study 2 demonstrated a good fit.

The moderated mediation model test revealed that moral anger played a mediating role between witnessed incivility and workplace ostracism against the instigator at higher levels of political skill (indirect effect = 0.09, Boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18]) compared to lower levels (indirect effect = 0.04, Boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.10]), leading to a statistically significant difference between these two effects (Diff = 0.05, Boot SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.01, 0.14]). When using apparent sincerity as a moderator, the same result pattern was observed: Moral anger mediated the relationship between witnessed incivility and workplace ostracism against the instigator. However, this mediation effect was stronger under conditions of higher levels of apparent sincerity (indirect effect = 0.13, Boot SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.04, 0.23]) compared to lower levels (indirect effect = 0.01, Boot SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.06]). The difference between these two effects was statistically significant (Diff = 0.12, Boot SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.03, 0.23]). In conclusion, the validity of this moderated mediation model has been confirmed, partially supporting Hypothesis 5a. Since Hypotheses 3b, 4a and 4c were not supported, the moderated mediation model proposed in Hypothesis 5b was also not established.

Table 5 summarises the assessments across two studies. Detailed interpretations of discrepancies (e.g., Hypotheses 3b and 4b) are discussed in the following section.

General discussion

We conducted two studies to investigate the effects of moral anger and political skill on third parties’ constructive responses to workplace incivility, employing a multi-method approach. The results largely supported our hypotheses, providing valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of workplace mistreatment and underscoring the need to consider individual differences in interpersonal interaction style and social efficacy when examining such phenomena. Overall, our research holds important theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

Our research makes contributions to the literature in the following ways. First, we examine the relationship between workplace incivility and workplace ostracism through the lens of third parties, providing insights into linking these two research fields (Cortina et al. 2017; Zhan and Yan 2021). Specifically, we identify instigator-oriented workplace ostracism as a potential deontic reaction by third parties to witnessed incivility. Previous research in Western workplace cultures has suggested that ostracising deviant members may serve to protect organisational functioning (O’Reilly 2013; Robinson et al. 2013), yet this may not apply within the Chinese cultural context. On the one hand, Chinese employees, guided by Confucian etiquette norms, may demonstrate greater sensitivity to workplace incivility, leading to more severe negative assessments of instigators and a stronger tendency to retaliate (Lin and Loi 2021; Zhan and Yan 2021). On the other hand, the cultural emphasis on harmony often induces employees to ignore incivility to avert conflict (Ferris et al. 2017; Iqbal et al. 2023). Our findings support the expectation that Chinese employees, as third parties, are prone to experiencing moral anger and taking action against instigators following the observation of incivility (Study 1), and that these responses exhibit durability over time (Study 2). Furthermore, our findings complement Ni et al.’s (2024) study by showing that third-party ostracism of incivility instigators is consistent regardless of whether the target of incivility is an external organisational member (e.g., a customer) or an internal one (e.g., a co-worker).

Second, the findings from our two sub-studies provide limited evidence to suggest that third parties react positively towards targets. Notably, this is consistent with previous research in the field, which indicates that the direct impact of observed mistreatment on target-oriented assistance is not significant (e.g., Mitchell et al. 2015; Priesemuth and Schminke 2019; Reich and Hershcovis 2015). These results imply that observers may not view low-intensity and ambiguous mistreatment, such as workplace incivility, as severe enough to warrant special attention to victims. Prior studies suggest that third parties are more likely to support the target only when they receive ambiguity-reduction cues (e.g., the target reacts hurt; Coyne et al. 2019; Jensen and Raver 2021). Conversely, in instances of subtle workplace incivility, third parties might struggle to assign responsibility for the mistreatment, potentially attributing blame to the two parties involved, which can result in indifference towards the victim or even a bias in favour of the instigator (Liu et al. 2021; Ni et al. 2024). Moreover, research has shown that merely witnessing workplace mistreatment can have negative effects on individuals (Dhanani et al. 2021), such as evoking fear (Gabriel et al. 2024), thereby reducing the likelihood of observers engaging in OCBs (Cortina et al. 2017). In addition, Reich and Hershcovis (2015) remark that third-party responses to targets of incivility should demonstrate “symmetry” with the specific experiences of those subjected to such acts, indicating that observers are more likely to respond to these individuals with more civility rather than through other forms of compensation. In essence, our study contributes novel insights into the responses of third parties to witnessed workplace incivility.

Third, our research extends the literature on the deontic model by examining the role of moral anger in motivating third-party constructive intervention in witnessed incivility. Consistent with the most recent meta-analysis (Hill et al. 2025), we find across two sub-studies that moral anger reliably mediates the relationship between witnessed incivility and punishment against the instigator. These findings support the notion that witnessed mistreatment, as a violation of moral norms, elicits a heightened state of arousal in the observer (Gabriel et al. 2024; Hill et al. 2025), which is closely associated with a strong inclination to punish the instigator (e.g., Priesemuth and Schminke 2019). Drawing on the perspectives of several researchers (e.g., O’Reilly and Aquino 2011; Mitchell et al. 2015; Reich and Hershcovis 2015), we also examine the role of moral anger in linking witnessed incivility to another deontic response—OCB-I. The results of this examination are mixed: We find an indirect effect of witnessed incivility on target-oriented assistance through moral anger in Study 1, but not in Study 2. This corresponds with Mitchell et al.’s (2015) observation that the mediating role of anger in the link between observed mistreatment and support for coworkers is dependent on particular conditions, such as when the third party holds a strong moral identity. These findings also suggest that anger is more closely associated with punishment rather than assistance (e.g., Jordan and Rand 2020; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005; van Prooijen 2010). Additionally, unlike in Study 1, a temporal discrepancy between the measurement of third-party emotional states and their subsequent behaviours is intentionally introduced in Study 2, reflecting that moral anger may be more likely to prompt immediate rather than delayed assistance behaviours. This is consistent with the proposition that moral anger is a transient emotional surge that compels rapid behavioural responses (Hill et al. 2025).

Fourth, the results of our research also add to the expanding literature on the boundary conditions of various stages of deontic effects (e.g., Lin and Loi 2021; Mitchell et al. 2015; Priesemuth and Schminke 2019). In particular, we direct our attention to a previously overlooked moderating variable—political skill—and simultaneously examine its influence on the two key stages of third parties’ deontic reactions to witnessed workplace incivility: the emotional and behavioural responses (Lin and Loi 2021). Concerning the emotional response, two sub-studies consistently reveal that political skill intensifies the deontic emotions felt by third parties witnessing workplace incivility—specifically, a more intense moral anger. This finding is consistent with the meta-theoretical framework of political skill’s effects (e.g., Munyon et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019), indicating that this individual attribute can impact intrapsychic processes—fostering a deeper understanding of oneself, others, and the work environment. Possessing this trait enhances individuals’ ability to perceive ambiguous workplace incivility and more adeptly understand their emotions. As shown by Lin and Loi (2021) and further supported by Jeong et al. (2023), such heightened unfairness perception and negative emotional interpretation can lead to stronger deontic emotions, thereby motivating constructive actions to protect the private self-identity of third parties—a perspective that aligns with the essence of the deontic model and the value-protection model (Priesemuth 2013).

However, third parties inevitably engage in a cost-benefit analysis when translating deontic emotions into constructive actions (Jensen and Raver 2021). One potential aspect of this analysis is the selection of the most self-serving means to maintain one’s public personal identity, thereby presenting a positive image to a wider audience (Skitka 2002). Our two sub-studies preliminarily confirm that political skill influences individuals’ strategic preferences for constructive intervention in witnessed incivility. Specifically, the behaviour of highly politically skilled third parties is not solely driven by emotion, as they also prioritise saving face and maintaining harmonious relationships with others (Liu et al. 2008). Although workplace ostracism is a relatively subtle form of punishment (O’Reilly 2013), it may still expose third parties to the risk of escalating conflicts with the instigator and be deemed a form of destructive punitive reaction (Lin and Loi 2021). This coping strategy is detrimental to the construction of their workplace network (Su et al. 2021), and thus it is avoided by them (as confirmed in Study 1).

Contrary to the expected hypothesis, the indirect relationship between witnessed incivility and the third party’s OCB-I towards the target via moral anger is weakened when political skill is high versus low (as confirmed in Study 1, with Study 2 showing marginally significant results). This may be due to third parties’ concerns about potential conflict and retaliation from instigators, leading them to moderate their support for victims due to self-protection concerns (O’Reilly 2013). Nevertheless, in a supplementary analysis of Study 1, we found that individuals with higher political skill (top 27% in political skill scores) still exhibited higher levels of OCB-I than those with lower political skill (bottom 27%) after witnessing workplace incivility (t(160) = 6.858, p < 0.001). This is consistent with established literature on political skill, suggesting that highly politically skilled third parties consistently demonstrate high levels of OCB (Kaur and Kang, 2023; Moon and Morais 2022) in an effort to engage in impression management and establish a positive reputation within the organisation (Brouer et al. 2015; Frieder et al. 2019). Overall, we identify an intriguing pattern among individuals with high political skill in dealing with witnessed incivility: they adopt a nuanced approach—neither confronting the instigator directly nor offering excessive support to the victim, but rather seeking to maintain a balanced stance that preserves relationships with all parties involved, thus fostering a broader network of connections.

Last, we provide evidence supporting the moderating effect of one dimension of political skill—apparent sincerity. However, the conclusion should be interpreted with caution because although individuals with high apparent sincerity report higher levels of moral anger, their self-reported emotional states may not always align with their true feelings (Jordan and Rand 2020). Their reports of intense moral anger may be solely a form of impression management to portray themselves as individuals striving for justice, rather than an authentic expression of such emotion. Future research is needed to corroborate these hypotheses with additional evidence.

Practical implications

Our findings have significant implications for workplace practice. Whereas third parties’ intervention in workplace incivility can raise the costs of rude behaviours and serve as deterrents to instigators (Reich and Hershcovis 2015), inappropriate reactions from third parties can have detrimental effects on organisations. For example, our research reveals that third parties may ostracise those who instigate incivility, which harms cooperation among organisation members and ultimately hinders organisational performance (Howard et al. 2020). Moreover, suffering from workplace ostracism may also push the initial perpetrator of incivility to instigate more uncivilised behaviours in retaliation, leading to a tit-for-tat progression (Ferris et al. 2017; Zhan and Yan 2021). Therefore, organisations should provide explicit provisions to urge employees to comply with workplace etiquette. In addition, relevant complaint channels should be established to encourage employees to resolve disputes in a rational way rather than answering violence with violence.

Consistent with previous studies, our research also shows that witnessing incivility can provoke third parties’ moral anger, prompting them to punish the instigator and provide assistance to the target (Reich and Hershcovis 2015; O’Reilly and Aquino 2011). However, it should be noted that moral anger is more strongly associated with punitive behaviours (e.g., Hill et al. 2025; Jordan and Rand 2020; Skarlicki and Kulik 2005; van Prooijen 2010). If employees are allowed to express their anger by engaging in excessive retaliatory behaviour, it may jeopardise the overall interests of the organisation. This motivates organisations to regularly train employees in emotion regulation to guide them to manage anger in a thoughtful manner. For example, third parties can be encouraged to give priority to helping behaviour (e.g., OCBs) to relieve negative emotions (Reich and Hershcovis 2015).

Finally, we argue that political skill, as an excellent quality of employees, can effectively assist individuals in managing mood swings and rationally resolving unexpected interpersonal conflicts in the workplace. Simultaneously, employees with high political skill maintain friendly relationships with other organisational members through consistently engaging in more OCBs, which is critical to fostering a harmonious organisational climate (Frieder et al. 2019). One plausible recommendation is to incorporate political skill as a vital criterion for employee recruitment and training.

Limitations and future directions

Our research is subject to certain limitations. One primary concern is the potential bias introduced by common method variance due to the reliance on single-source data. Despite this limitation, we assert that the collection of same-source data is essential for achieving our research objectives. We focus on the responses of third parties to specific instigators or targets of incivility, such as their emotional and behavioural responses to the critical incident, which can only be reliably reported by the respondents themselves (Mitchell et al. 2015). In addition, mistreatment in the workplace, such as incivility and ostracism, often manifests in subtle forms, posing challenges for coworkers and supervisors to recognise these deviant behaviours displayed by other colleagues (Ferris et al. 2017; Mitchell et al. 2015). As a result, self-reported sensitive information may yield more precise assessments (Berry et al. 2012). In Study 2, we controlled for common method variance by manipulating the time interval between predictor and criterion variables. However, the 1-week gap we implemented may not adequately minimise the effects of common method variance, as the literature suggests that a minimum of 2 weeks is more effective in reducing this issue (Mitchell et al. 2015; Priesemuth and Schminke 2019).

Second, an exclusive focus on hypothetical and recall techniques may compromise the validity of research findings (Hershcovis et al. 2017). In Study 1, the hypothetical vignettes reflected third parties’ behavioural intentions rather than their actual actions, raising doubts about the external validity of the results. To overcome this limitation, Study 2 utilised a critical incident design that facilitated the investigation of actual responses to witnessed incivility in a real work environment. However, this approach is also retrospective in nature and still suffers from interference such as recall accuracy and social approval. It is recommended that future research adopt a field experimental design that allows for the manipulation of witnessed incivility and enables observation and measurement of third parties’ authentic reactions, thereby enhancing the ecological validity of the study (Reich et al. 2021; Reich and Hershcovis 2015).

Last, several core variables in this research were assessed using tools from Western culture. Variables like workplace ostracism might be quite different in China in their dimensions and manifestations (Ferris et al. 2017). Chinese organisational members place a high value on preserving harmonious interpersonal relationships. Consequently, those who engage in workplace ostracism typically employ more hidden and discreet tactics. This type of ostracism usually does not involve harsh language or obvious behaviour. Instead, it happens quietly to exclude the individual (Su et al. 2021). Furthermore, some scholars have argued that Political Skill Inventory (PSI) may not be completely applicable in the Chinese workplace because this scale fails to capture certain unique aspects of political skill in Chinese culture, such as face-saving and guanxi-maintaining (Liu et al. 2008; Lvina et al. 2012). Additionally, there is also an ongoing debate regarding the cultural applicability of specific sub-dimensions of political skill, particularly apparent sincerity. This is because displaying genuine emotions is viewed as immature and irrational in Chinese culture (Wu and Yang 2019), which differs from individualistic cultures that prioritise authentic expression (Brouer et al. 2015). These issues might explain why our research did not confirm the moderating effect of a political skill sub-dimension. To sum up, researchers must carefully select tools that correspond to the workplace culture of their study in order to assess the cross-cultural validity of their findings in subsequent research.

Conclusion