Abstracts

Enhancing the level of agricultural mechanization services in all countries is essential to guarantee global food security and improve rural pollution. This paper empirically analyzes the impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on the level of agricultural mechanization services in rural areas using a fixed-effects model based on the collection of Chinese provincial panel data from 2011 to 2022. The research in this paper will provide policy recommendations for the modernization of agriculture and the development of inclusive finance in various countries worldwide. After analyzing this paper, the following conclusions are drawn: 1. the development of digital inclusive finance can effectively improve the use of agricultural mechanization services in rural areas. 2. the level of human capital has a moderating role between the two. 3. There is a threshold effect between Digital Financial Inclusion and agricultural mechanization services. 4. There is heterogeneity in the impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on agricultural mechanization services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is estimated that by 2050, the global population will reach 10 billion, and the demand for food will increase by 50% compared to 2010 (Rahaman et al., 2021). Food security is a primary concern for countries around the world. China’s grain output in 2023 was 695.41 million tons (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023). According to the 2024 Statistical Yearbook of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, China is the world’s third largest food exporter in gross weight. China plays an important role in ensuring global food supply (Huang et al., 2017).

However, with the accelerating pace of urbanization, there is a potential threat to food security worldwide, including China. The transfer of agricultural labour to non-agricultural industries (Leng et al., 2021), the rapid ageing of the agricultural population, and the gradual feminization of the rural labour force are becoming increasingly prominent (J. Liu et al., 2023; Y. Liu & Zhou, 2021; H. Lu et al., 2019), and there are serious challenges to the sustainability of agricultural production (H. Lu & Huan, 2022). In addition, as the global demand for food continues to increase, the use of elements such as agricultural fertilizers and pesticides is also gradually increasing, leading to serious agricultural pollution problems. It is estimated that by 2050, greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture will account for half of the world’s total planned emissions, and the problem of agricultural pollution needs attention.

Countries worldwide are, therefore, trying to improve agricultural production efficiency to achieve the synergistic goals of increasing food production while reducing pollution (Ashraf & Javed, 2023). Among these, promoting the development of agricultural modernization is key (X. Li & Fu, 2023). In China, for example, a series of measures have been formulated to improve agricultural modernization (X. Zhou et al., 2020), and improving the level of agricultural mechanization services (AMS) has become one of the important ways (S. Yang & Zhang, 2023). AMS in China is usually provided by public welfare institutions established by the government, rural cooperative organizations, private enterprises, etc. (H. Qiu et al., 2023). AMS promotes agricultural production with agricultural mechanization operations and ensures food security (Chen, Rizwan, et al., 2022). The rise of AMS will break the original production structure, improve the agricultural ecological environment, and enhance the efficiency of agricultural production (X. Li & Fu, 2023), thereby effectively coordinating production and environmental development. Therefore, it is of practical significance to explore how to improve the level of AMS effectively.

The effective development of the AMS service market is closely related to market supply and demand. The AMS market is the result of the convergence of inputs of factors of production for modern agricultural production and demand for AMS. Its sustainable development depends on the pooling of financial resources (Yan et al., 2022). In traditional financial institutions, it is difficult for agricultural groups such as agricultural machinery service users and farmers to obtain financial resources (Su et al., 2021). This may encourage farm machinery service providers to invest in factors like farm machinery and equipment. On the other hand, it may even restrict the behaviour of smallholder farmers in purchasing farm machinery services. It can be seen that traditional finance cannot deeply reach rural residents (T. Liu et al., 2021).

To this end, policymakers worldwide are actively exploring solutions to improve financial inclusion to achieve social goals such as poverty reduction and economic growth. For example 2002, Banco Azteca was founded to serve Mexico’s low-income population. It supports the economic development of low-income groups through an extensive service network and a diverse range of financial products. In 2010, China began exploring the path of building digital finance inclusive (DFI) to support comprehensive and inclusive economic and social development and improve financial services’ coverage, efficiency, and affordability through technological innovation (X. Ji et al., 2021).

DFI broadens the financial boundaries and brings financial resources into rural life and farmers’ production (Kamble et al., 2023; Lin et al., 2022). In 2005, the United Nations proposed the concept of inclusive finance (Luo & Li, 2022), which aims to improve the accessibility of financial services in countries worldwide by improving the financial infrastructure (Aziz & Naima, 2021; X. Wang & Fu, 2021). The diversified service scope and less financing constraints on users of China DFI make it possible for DFI to make up for the deficiencies of traditional finance and achieve the goal of promoting the efficient allocation of financial resources (D. Fang & Zhang, 2021; Goedecke et al., 2018; He & Shen, 2021; Xiao et al., 2022). Can the generation of DFI promote the development of the AMS market? This article will examine this question.

Literature review and theoretical hypotheses

Literature review

Research on AMS

At present, countries around the world are paying more and more attention to the development of agricultural modernization (A. Yang et al., 2024), and improving the level of agricultural mechanization has become an important way for countries to promote the development of agricultural modernization (Akdemir, 2013; Houssou et al., 2013). Many scholars have studied the impact of the development of AMS, which is mainly reflected in three aspects.

First, AMS can improve the comprehensive production capacity of grain and ensure national food security. With the development of society, the differentiation of urban and rural incomes has led to an accelerated transfer of the agricultural labour force, and changes in the population structure have led to an accelerated ageing of the agricultural labour force (Gao et al., 2020; Leng et al., 2021). Adequate labour supply for agricultural production has decreased, hurting national food security. The use of AMS can improve the comprehensive production capacity of grain (Cai et al., 2022; Emmanuel et al., 2016; Knickel et al., 2017; Y. Liu et al., 2014; T. Qiu et al., 2021; Verkaart et al., 2017; Yamauchi, 2016; Q. Yang et al., 2023).

Second, AMS can increase farmers’ income and consolidate the country’s achievements in poverty alleviation. In 2020, China achieved complete success in the battle against poverty and completed the arduous task of eradicating absolute poverty (Wan et al., 2021). Due to farmers’ weak risk-coping ability, there is a risk of falling back into poverty (Hallegatte et al., 2020). Increasing the use of agricultural machinery and equipment has become an important way to reduce the impact of this hidden danger and consolidate the provision of poverty alleviation (Ali et al., 2016; Benin, 2015; Jena & Tanti, 2023; H. Qiu et al., 2023; J. Yang et al., 2013).

Third, AMS can guide farmers’ green behaviour decisions and promote the transformation of green development in agriculture. Agricultural pollution is still a problem in many countries worldwide and has become a barrier limiting the further development of agriculture in various countries (X. Li & Fu, 2023). It is urgent to achieve green development in agriculture (Cabral et al., 2022; Qing et al., 2023). AMS can promote the green transformation of agriculture (X. Li & Guan, 2023; Qing et al., 2023; Q. Xu et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022).

From the above three aspects, we can see the importance of developing AMS, so it is of great significance to study how to promote the level of AMS. In the existing literature, some scholars have studied the impact of factors such as cultivated land area, agricultural machinery purchase subsidies, farmers’ age and education level, and rural pension insurance on AMS (Hu, 2022; Tamirat et al., 2018; Q. Yang et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2021). However, more research is needed on how to promote AMS from this perspective. Therefore, this paper studies how to promote AMS from the perspective of promoting capital pooling.

Research on DFI

DFI plays an important role in promoting rural construction and development, and many scholars have also conducted research on this, mainly including the following three aspects. First, DFI can reduce the vulnerability of farmers to poverty and narrow the gap between urban and rural wealth (X. Wang & He, 2020). DFI can alleviate the credit constraints of farmers, provide opportunities for farmers to start entrepreneurial activities, and promote entrepreneurial behaviour among farmers, thereby narrowing the gap between urban and rural wealth (X. Ji et al., 2021; T. Liu et al., 2021).

Second, DFI can solve the problem of the “last mile” of financial services and increase the availability of financial services to farmers (Suri et al., 2021; Xia & Kong, 2024). For example, China encourages farmers to form new types of agricultural management entities, and the establishment of new types of agricultural management entities requires a large amount of capital investment. As a result, farmers have an increased need for credit and would like more access to various financial services (Tkach et al., 2019). The availability of DFI services is more significant for farmers (Y. Liu et al., 2021; J. Wang et al., 2023). This is because farmers are excluded from traditional financial institutions and are unlikely to obtain financial resources from them (Carter, 2022; Y. Li et al., 2022).

Third, DFI can promote the use of agricultural technology and increase agricultural output. Low-cost, specific services enhance farmers’ willingness to adopt agricultural technology, thereby boosting agricultural production (Z. Zhou et al., 2022). It can be seen that the development of a mature rural financial system can promote agricultural production (An et al., 2023).

In summary, DFI has significantly contributed to narrowing the gap between the rich and the poor, improving the availability of financial services to farmers, and increasing agricultural output. Research on the role of DFI is, therefore, of great significance. Some studies have shown that DFI can improve the use of agricultural technology (Z. Zhou et al., 2022). DFI has a positive impact on the modernization of agriculture. However, can DFI also improve AMS levels? This question remains to be studied.

Research on the relationship between DFI and AMS

As seen from the above literature analysis, it is of great practical significance to explore the factors that influence the improvement of AMS and the role played by DFI in rural construction. Few studies analyze the relationship between DFI and AMS levels in existing articles, and those mainly focus on improving agricultural mechanization (C. Liu et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2023; H. Zhang et al., 2023).

Literature review

The following characteristics of related research in this field are found through literature collation and analysis. First, in AMS research, many documents expound on the importance of AMS, but there are relatively few studies on how to promote AMS levels. Second, in DFI research, many scholars have studied the role of DFI in agricultural construction, but there have been fewer studies on its impact on AMS levels. Third, in the rare literature that studies the relationship between the two, most only study AMS as an intervening variable, and only some scholars directly explore the relationship between DFI and AMS. Fourth, in the rare literature that studies the relationship between the two, the focus is mainly on exploring the linear relationship, ignoring the study of the nonlinear relationship between the two.

In summary, the contributions of this study to the existing literature are as follows. 1. This paper expands research in two areas. 2. This paper verifies that human capital plays a moderating role between the level of DFI and AMS. 3. This paper uses a threshold model to study the nonlinear relationship between the two, which enriches research in this field.

Theoretical hypotheses

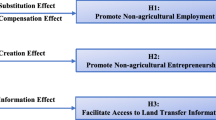

DFI and AMS

The AMS market is made up of both supply and demand. DFI not only increases the supply of AMS but also expands the demand for AMS.

On the demand side, AMS adoption is an effective way to help farmers access farm equipment (Van Loon et al., 2020). AMS providers must aggregate farmer demand to realize economies of scale, which can compensate for losses due to high initial investment and attract supply-side entry into the AMS market (Q. Lu et al., 2022). Between the 1950s and the early 1980s, African governments provided large numbers of farm tractors in an unsuccessful attempt to advance agricultural mechanization in the form of AMS. The main reason for this was the shortage of funds for farmers at the time and the lack of actual demand for such services by farmers (Benin, 2015). It can be seen that the availability of capital becomes a key factor influencing farmers’ demand for AMS, which plays a vital role in the development of AMS markets (T. Qiu & Luo, 2021). However, in the rural credit market, farmers lack the necessary financial collateral, and “credit exclusion” has become a common choice of financial institutions, making most farmers suffer from liquidity constraints in the production process (Mottaleb et al., 2016; L. Zhou & Takeuchi, 2010). This problem can be mitigated by the emergence of DFI, which reduces farmers’ credit constraints and can somewhat alleviate their liquidity constraint dilemma (Ma et al., 2023).

On the supply side, most of the farmers’ private activities require the government sector’s intervention due to market failures (Feder et al., 2011). However, the personal nature of farm equipment provides feasibility for farmers to invest in farm machinery for private AMS (Adu-Baffour et al., 2019). Moreover, the AMS market in China is relatively mature. AMS, through a personal approach, can respond to market demand faster and more sensitively and can better enhance the use of AMS (Diao et al., 2014). Therefore, the leading actors in large-scale farm machinery investment are still the agricultural machinery service households (Mottaleb et al., 2017; M. Xu et al., 2024).

Despite the increase in the share of farm machinery purchase subsidies in farm machinery inputs (M. Xu et al., 2024), the marginal contribution of subsidies to the ability of agricultural machinery service households to purchase machinery has seen little effect compared to the increasing value of farm machinery (X. Wang et al., 2018). It can be seen that agricultural machinery service households still need to utilize a significant portion of their own or borrowed funds to meet the financial requirements for acquiring agricultural machinery (Akram et al., 2020; X. Li et al., 2024). However, financial constraints also exist on the supply-side of the AMS market. Farmers without agricultural machinery perceive the cost of equipment purchase to be high, and agricultural machinery owners perceive the cost of machine maintenance to be high (Huo et al., 2022), which makes there a financial barrier for agricultural machinery service households to enter the AMS market. In response to this problem, and the same vein as the demand-side analysis, the emergence of DFI may alleviate the problem of supply-side financial thresholds.

In summary, DFI not only promotes the input of production factors in the agricultural service market but also increases the market demand (C. Zhang et al., 2023), which may contribute to the use of AMS.

H1: DFI can significantly enhance the use of AMS

Moderation effects

On the one hand, good digital quality of farmers is an essential prerequisite for facilitating the effective penetration of DFI in rural areas (Ma & Li, 2021), i.e., the penetration of DFI is also higher in areas with higher level of human capital (Lin et al., 2022; Niu et al., 2022). However, the reality of low human capital exists in rural households. In this context, rural residents are prone to reject digital finance (X. Ji et al., 2021), undermining the role of DFI in increasing AMS utilization (Y. Li et al., 2022). On the contrary, improving human capital positively affects an individual’s digital literacy. Specifically, digital literacy can enhance the resilience of village populations to use digital products. It creates more space for DFI demand in rural areas, thus strengthening DFI’s impact on AMS use.

On the other hand, increasing the level of human capital can effectively promote the use of AMS. It has been proven that the achievement of agricultural modernization will be challenged if the government disregards the needs of farmers’ quality education and adopts a “leapfrog” mandatory approach to promote agricultural mechanization (Benin, 2015; Shen et al., 2024; Van Loon et al., 2020). On the contrary, if farmers are well-educated and digitally literate (Shen et al., 2024), it is highly probable that they will voluntarily increase the demand for agricultural mechanization and adopt advanced technologies to improve agricultural production (Adnan et al., 2018).

H2: Human capital levels can contribute to the positive impact of DFI on increasing AMS use.

Threshold effect

The above theoretical analysis shows that the development of DFI can improve the level of AMS, and this promoting effect may have a specific threshold effect.

When DFI development is low, DFI cannot integrate well with the AMS market, and the “productivity paradox” may occur. In theory, considering the network externalities of the digital economy and the Metcalfe Law of increasing marginal effects (M. Zhou et al., 2024), the independent driving effect of DFI on the level of AMS shows a gradually increasing nonlinear characteristic (Tao et al., 2020). With the gradual improvement of cutting-edge technological research and development capabilities, the application scenarios of DFI have been expanded, the pool of high-end talent has been expanded, the marginal cost of inter-industry linkage development has gradually decreased, the exchange and cooperation between DFI departments has continued to be smooth, and the “digital dividend” released has been greatly improved (Xiaodong et al., 2022). With the popularization of DFI, the development of the AMS market is promoted by alleviating the financing constraints on both the supply and demand sides, which fully releases the digital dividend effect and significantly improves the level of AMS (Y. Liu et al., 2023).

In addition, when the per capita income of rural residents exceeds the threshold, DFI services will become more effective, promoting the development of AMS. Specifically, on the one hand, financial inclusion theory emphasizes universal and equal access to financial services. The increase in rural residents’ per capita income has made more funds available for financial investment and consumption. After receiving dividends, income reaching a certain threshold will place greater demands on the scale and efficiency of DFI development (M. Wang et al., 2023). On the other hand, economic growth theory holds that increasing income levels can promote consumption and investment, which will drive economic growth. DFI increases the income of rural residents by providing convenient financial services. This growth effect becomes more pronounced when income reaches a certain threshold, helping boost consumption and, thus, the development level of the AMS. Therefore, when the per capita income of rural residents increases beyond the threshold, the effectiveness of DFI services will be improved, and the development of AMS will be promoted. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed. The hypothesis logic diagram of this paper is shown in Fig. 1.

H3: There is a threshold effect of DFI on the use of AMS.

H4: Income per capita of the farming population has a threshold effect between the two.

Materials and methods

Model

Baseline regression model

To test hypothesis H1, the research model set up in this paper is as follows.

In model (1), i is the province, t is time. CONXit is a series of control variables, λi is the province fixed effect, εit is the random error term.

Moderator regression model

Drawing on related studies (J. Fang et al., 2015), the moderation effects were modeled as.

In Eq. (2), HCLit is the human capital level, lnDFIit×lnHCLit is the interaction term between DFI and the human capital level.

The symbols of Eq. (3) are expressed in the same way as above and will not be repeated.

Threshold regression model

To verify the threshold effect, the model is set as follows concerning previous studies (Hansen, 1999):

In model (4), I () is the indicative function. \({\omega }_{{it}}\) is the threshold variables, and γis the threshold to be estimated.

Variables

1. Dependent variable: AMS (lnAMS). Referring to related scholars’ research, the level of AMS is measured by per capita total agricultural machinery service income (Y. Yang & Lin, 2021). 2. Explanatory variable: DFI (lnDFI), measured using the China DFI Index compiled by the Digital Finance Center at Peking University, and also including three secondary indicators of DFI coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitalization (lnBRE, lnDEP, lnDIG) (Cheng et al., 2023). 3. Control variables: Based on existing research (Y. Ji et al., 2017; C. Liu et al., 2023), the proportion of crops affected by disasters (lnPCA), the level of urbanization development (lnCITY), industrial structure upgrading (lnIS), the level of agricultural-related loans (lnAL), and the rural elderly dependency ratio (lnOAD) were selected. 4. Regulating variable: Human capital level (lnHCL) is expressed using the average years of schooling in rural areas. 5. Threshold variable: It is expressed using the DFI index (lnDFI) and using the per capita income of rural residents (lnINC) (Jiao & Xu, 2022).

The data for this study were obtained from China Agricultural Machinery Industry Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook, China Agricultural Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, China Agricultural Products Import and Export Monthly Statistical Report, and the statistical yearbooks of each province for the past years, and the descriptive results of each variable using the data at the use of 30 provinces (cities) in the country for the period of 2011–2022 are shown in Table 1.

Regression results

Baseline regression results

Table 2 shows the baseline results of the regression analysis, which are analyzed as follows. First, through the multicollinearity test, the VIF of each variable is less than 10, indicating no multicollinearity problem. Second, the F-test value is 71.53, and the Hausman test χ2 (7) value is 28.67, both significant at the 1% level. Therefore, this paper uses a fixed-effect model for analysis. Finally, column (3) of Table 2 analyzes the data. DFI significantly contributes to the level of AMS, and the analysis results verify H1. Regarding other control variables, the industrial structure upgrading index significantly positively impacts the level of AMS. The reason for this is that industrial structure upgrading helps to achieve coordinated development of various production sectors within the agricultural system and improve the efficiency of agricultural production and management (J. Zhou et al., 2023), which helps to increase farmers’ operating income and their willingness to adopt AMS field services.

Robustness tests

The following robustness tests were conducted to test the article’s hypotheses, and the results are shown in Tables 3 and 4. 1. Substitute explanatory variables. This paper selects the first-order lag term (L.lnDFI) and the second-order lag term (L2.lnDFI) of digital financial inclusion as new explanatory variables to substitute and test the robustness of the estimation results. The regression results in columns (1) and (2) are both significant at the 1% level. 2. Change the sample size. Due to the rapid development of the digital economy in municipalities, this may exaggerate the impact of digital inclusive finance on agricultural socialization services. After excluding the sample of municipalities, the result in column (3) is still significant. 3. Winsorization. All continuous variables were winsorized by 2.5% to avoid the influence of extreme values on the data. The results in column (4) remained significant. 4. Add control variables. For regression, this paper adds variables such as the proportion of agricultural expenditures, crop planting structure, and the scale of cultivated land operations. The regression results in column (5) are all significant at the 1% level. 5. Panel quantile regression. Regressions were conducted using quantiles 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75, and the results in Table 4 are significant. The above robustness tests verify Hypothesis 1.

Endogeneity test

The endogeneity discussion of the study involves two main aspects: the issue of reverse causation, where an increase in the use of AMS can accelerate the transmutation of traditional agricultural development into modern agricultural development, leading to a more rationalized approach to agricultural production. In this context, farmers will be driven to actively turn to exogenous financing channels to mechanize production and improve productivity, which will, in turn, have a catalytic effect on DFI. Second, the problem of omitted variables: many factors affect the use of AMS. However, a series of variables, such as crop cultivation structure and urbanization development level, have been controlled (Y. Li et al., 2022), and other important influencing factors may still be ignored, resulting in errors in the model setting.

Therefore, to address the endogeneity issue, this study uses the instrumental variable analysis method to test the findings’ robustness. First, the DFI lagged first-order term is chosen as the instrumental variable for the regression, and the results are shown in column (1) of Table 5, where the data indicate that the development of DFI in the previous year helps to promote the current AMS level. Second, drawing on the experience of using landline penetration as an instrumental variable for DFI as proposed in an existing article (Qian et al., 2020), this study concludes by choosing the number of landline telephones per 100 people (lnPHONE) in 1984 for each province in history as the instrumental variable. On the one hand, landline penetration is the basis for the application of Internet technology, and the development of DFI depends on the development of Internet technology. Thus, the development of DFI stems from landline penetration, which allows the number of landline phones to satisfy the relevance of the instrumental variables. On the other hand, the number of historical landline calls has little effect on the use of AMS, making it satisfy the exclusivity of the instrumental variable. In this study, the number of landline telephones per 100 people in 1984 in the historical provinces is regressed as an instrumental variable. The regression results, as shown in column (2) of Table 5, show that DFI can still positively impact the use of AMS. The conclusion is still strongly validated after considering endogeneity issues.

In addition, for the test of the original hypothesis of “insufficient identification of instrumental variables”, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic is 30.839, which rejects the original hypothesis at the 1% significance level. In the test of the original hypothesis of “weak identification of instrumental variables,” the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic is 45.303, greater than the critical value at the 10% level of the Stock-Yogo test, and the original hypothesis is rejected. The “homogeneity of instrumental variables” and “the existence of overidentification” are judged by the Hansen J statistic, and the results show that the selected instrumental variables are exogenous and there is no overidentification. Overall, the selection of instrumental variables is reasonable.

Heterogeneity test

Dimensions of DFI

The DFI index contains three secondary indices in addition to the composite index: breadth of coverage index (lnBRE), depth of use index (lnDEP), and digitization index (lnDIG). This paper further investigates the effects of DFI in the development of AMS from these three different dimensions. The analysis’s findings are presented in Table 6, which indicates that all three indices have a positive impact on the use of AMS. Among these, the facilitation utility of depth of DFI use was the strongest, while the utility of degree of digital input was the weakest. This suggests that the development of DFI has eased farmers’ financial constraints and provided a good external environment for them to actively purchase farm machinery and mechanize their production. However, there is still a demand for further improvement and strengthening of digital architecture.

East-central-west regional

In this paper, the sample cities are grouped into eastern, central, and western cities to check the effect of DFI on AMS use in different regions, and the findings are shown in columns (1) through (3) of Table 7. The results show that DFI’s positive impact on the level of AMS in central eastern cities is lower than that in western cities. This may be because, from the viewpoint of traditional financial development, it is more challenging for farmers in the western region to obtain financial services than in the central and eastern parts of the country. The lack of traditional financial supply capacity in Western cities makes DFI more vital in serving farmers (Bai et al., 2023).

Food-producing regions and non-food-producing regions

China has 13 major food-producing regions that focus on the cultivation of grain crops. The intensity of use of farm equipment will be higher in the food-producing regions than in the non-food-producing regions. This paper divides the sample into food-producing regions and non-food-producing regions and performs regression analysis separately. The results are shown in columns (4) and (5) of Table 7. It can be seen that the effect of digital inclusion on AMS utilization is significant in both food-producing regions and non-food-producing regions. However, this effect is more significant in non-food-producing areas. This may be due to the saturation of the use of farm equipment in developed agricultural areas, making the role of DFI less obvious (Chen, Yang, et al., 2022; S. Wang et al., 2021).

Moderator effect result

The results of the test of the moderating effect of human capital level are reflected in Table 8 of the paper. As shown in column (1), the regression result of DFI and human capital level is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the human capital level is moderating and supports H2. As can be seen from columns (2) to (3), the regression results of the interaction term between DFI and human capital level are significant in both production areas, indicating that the level of human capital has a significant moderating effect. Overall, the higher the level of human capital, the greater the impact of DFI on the level of AMS. Improving human capital lays the foundation for the deeper development of DFI. As farmers’ education levels increase, their acceptance of DFI will improve. After receiving funds, farmers will promote the input of production factors in the AMS market and will also be more inclined to choose to use AMS, thus promoting its use.

Threshold effect test result

This paper uses the bootstrap method to test the existence of critical effects. As shown in Table 9, the results show only one critical effect between DFI and income per capita of the farming population. This is because the two threshold variables passed the single threshold test, but neither passed the double threshold test. In addition, the critical values of the two are 5.8784 and 9.1964, respectively. At the same time, DFI has a significant positive contribution to the use of AMS within the critical value interval Table 10.

Table 11 presents the regression results with DFI and income per capita of the farming population as threshold variables. First, DFI is used as a threshold variable. For DFI levels below 5.8784, the regression coefficient is 0.038, which has a positive effect at the 1% level. For DFI levels above 5.8784, the regression coefficient is 0.047, which has a positive effect at the 1% level. With the gradual increase in the level of development of DFI, the driving effect of DFI on the use of AMS shows a clear enhancement trend. Therefore, the threshold effect of DFI exists, and hypothesis 3 holds.

Second, the income per capita of the farming population is used as the threshold variable. When rural per capita income is lower than 9.1964, the regression coefficient is 0.042, which is significant at the 1% level. When it is higher than 9.1964, the regression coefficient is 0.048, which is significant at the 1% level. This suggests that the contribution of DFI to AMS utilization among farm households has increased significantly as the income per capita of the farming population continues to rise. Therefore, the threshold effect of income per capita of the farming population exists, and hypothesis 4 holds.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper uses panel data from 30 provinces in China from 2011 to 2022 to construct a fixed-effect model to verify whether DFI can improve the level of AMS. The study found that (1) DFI improves the level of AMS, and this conclusion remains robust after robustness tests and endogeneity tests. (2) The level of human capital plays a positive moderating role between the level of DFI and the level of AMS. (3) DFI can improve AMS in terms of coverage, depth of use and degree of digitization, but the positive effect varies. (4) Among the eastern, central and western regions, the western region’s DFI has the greatest positive effect on the AMS level. (5) DFI in both the main food and non-food-producing areas can improve the AMS level, but this effect is more significant in the non-food-producing areas. (6) The contribution of DFI to the level of AMS has a nonlinear characteristic of increasing marginal effect, and there is a significant threshold effect on the per capita income of rural residents.

The research in this paper provides some evidence for DFI’s policy prospects in the high-quality development of agriculture and rural areas, which can serve as a reference for decision-making on subsequent institutional arrangements.

First, Policymakers in parts of the world with situations similar to those in China (global policymakers) can develop DFI by completing the digital communications infrastructure. The development of DFI can reduce the number of financially excluded groups in poor areas and achieve social goals such as poverty alleviation and food security.

Second, upgrading human capital is a prerequisite for farmers to enjoy the dividends of DFI. Therefore, global policymakers must focus on digital financial education for the population while popularizing DFI.

Third, if global policymakers want DFI to promote agricultural modernization, they must ensure that farmers’ incomes are reasonably stable. Therefore, policymakers in various countries need to focus on implementing a series of rural revitalization initiatives that can safeguard the interests of farmers while focusing on the spread of DFI.

Fourth, global policymakers should ensure that DFI delivery platforms can provide differentiated DFI services to farmers in different regions, land types, and cultivation sizes by accurately targeting their audiences.

Fifth, optimize DFI products and services. Financial institutions should explore and develop diversified financial products that meet the needs of local customers, especially financial services for AMS, such as mortgages for agricultural assets such as farm machinery and greenhouse facilities.

Sixth, regional policies should encourage agricultural machinery service organizations to provide diversified services, such as “nanny-style” full trusteeship and “menu-style” multi-link trusteeship services, to meet the needs of different farmers.

Finally, each region can establish and improve a DFI risk compensation and mitigation mechanism to reduce financial risks, guide financial institutions in developing DFIs, and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

Limitations and prospects

Gender and age may affect access to and utilization of financial services. Therefore, in future research, it would be progressive to use microdata for specific studies to analyze the impact of the development of financial institutions on agricultural modernization.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Adnan N, Nordin SM, Ali M (2018) A solution for the sunset industry: adoption of green fertiliser technology amongst Malaysian paddy farmers. Land Use Policy 79:575–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.08.033

Adu-Baffour F, Daum T, Birner R (2019) Can small farms benefit from big companies’ initiatives to promote mechanization in Africa? A case study from Zambia. Food Policy 84:133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.03.007

Akdemir B (2013) Agricultural mechanization in Turkey. IERI Procedia 5:41–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ieri.2013.11.067

Akram MW, Akram N, Wang H, Andleeb S, Ur Rehman K, Kashif U, Hassan SF (2020) Socioeconomics determinants to adopt agricultural machinery for sustainable organic farming in pakistan: a multinomial probit model. Sustainability 12 (23):Article 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239806

Ali A, Bahadur Rahut D, Behera B (2016) Factors influencing farmers׳ adoption of energy-based water pumps and impacts on crop productivity and household income in Pakistan. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 54:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.073

An C, He X, Zhang L (2023) The coordinated impacts of agricultural insurance and digital financial inclusion on agricultural output: evidence from China. Heliyon, 9 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13546

Ashraf J, Javed A (2023) Food security and environmental degradation: do institutional quality and human capital make a difference? J Environ Manag 331:117330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117330

Aziz A, Naima U (2021) Rethinking digital financial inclusion: evidence from Bangladesh. Technol Soc 64:101509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101509

Bai H, Wu Y, Wang R (2023) Does digital financial inclusion lead to regional differences in trade credit financing?: A quasi-natural experiment. Econ. Anal Policy 80:1475–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2023.10.023

Benin S (2015) Impact of Ghana’s agricultural mechanization services center program. Agric Econ 46 (S1):103–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12201

Cabral L, Pandey P, Xu X (2022) Epic narratives of the Green Revolution in Brazil, China, and India. Agric Hum Values 39 (1):249–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10241-x

Cai B, Shi F, Huang Y, Abatechanie M (2022) The impact of agricultural socialized services to promote the farmland scale management behavior of smallholder farmers: empirical evidence from the rice-growing region of southern China. Sustainability 14 (1):Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010316

Carter MR (2022) Can digitally-enabled financial instruments secure an inclusive agricultural transformation? Agric Econ 53 (6):953–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12743

Chen T, Rizwan M, Abbas A (2022) Exploring the role of agricultural services in production efficiency in chinese agriculture: a case of the socialized agricultural service system. Land 11 (3):Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030347

Chen T, Yang J, Chen C (2022) Mechanism and path of agricultural mechanization promoting income increase: based on the separability of agricultural production links. J Huazhong Agric Univ 4:129–140. https://doi.org/10.13300/j.cnki.hnwkxb.2022.04.011

Cheng X, Yao D, Qian Y, Wang B, Zhang D (2023) How does fintech influence carbon emissions: evidence from China’s prefecture-level cities. Int Rev Financ Anal 87:102655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102655

Diao X, Cossar F, Houssou N, Kolavalli S (2014) Mechanization in Ghana: emerging demand, and the search for alternative supply models. Food Policy 48:168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.013

Emmanuel D, Owusu-Sekyere E, Owusu V, Jordaan H (2016) Impact of agricultural extension service on adoption of chemical fertilizer: implications for rice productivity and development in Ghana NJAS: Wagening J Life Sci 79(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2016.10.002

Fang D, Zhang X (2021) The protective effect of digital financial inclusion on agricultural supply chain during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from China. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 16 (7):Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070174

Fang J, Wen Z, Liang D, Li N (2015) Moderation effect analyses based on multiple linear regression. J Psychol Sci 38 (03):715–720. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2015.03.001

Feder G, Birner R, Anderson JR (2011) The private sector’s role in agricultural extension systems: potential and limitations. J Agribus Dev Emerg Econ 1 (1):31–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/20440831111131505

Gao J, Song G, Sun X (2020) Does labor migration affect rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 99:105096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105096

Goedecke J, Guérin I, D’Espallier B, Venkatasubramanian G (2018) Why do financial inclusion policies fail in mobilizing savings from the poor? Lessons from rural south India. Dev Policy Rev 36 (S1):O201–O219. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12272

Hallegatte S, Vogt-Schilb A, Rozenberg J, Bangalore M, Beaudet C (2020) From poverty to disaster and back: a review of the literature. Econ Disasters Clim Change 4 (1):223–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00060-5

Hansen BE (1999) Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: estimation, testing, and inference. J Econ 93 (2):345–368

He G, Shen L (2021) Whether digital financial inclusion can improve capital misallocation or not: a study based on the moderating effect of economic policy uncertainty. Discret Dyn Nat Soc 2021:e4912836. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4912836

Houssou N, Diao X, Cossar F, Kolavalli S, Jimah K, Aboagye PO (2013) Agricultural mechanization in Ghana: is specialized agricultural mechanization service provision a viable business model? Am J Agric Econ 95 (5):1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat026

Hu X (2022) Effects and appraisal of grain subsidy policy based on statistical analysis. Math Probl Eng 2022:e2893486. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2893486

Huang J, Wei W, Cui Q, Xie W (2017) The prospects for China’s food security and imports: will China starve the world imports? J Integr Agric 16 (12):2933–2944. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61756-8

Huo Y, Ye S, Wu Z, Zhang F, Mi G (2022) Barriers to the development of agricultural mechanization in the North and Northeast China plains: a farmer survey. Agriculture 12 (2):Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020287

Jena PR, Tanti PC (2023) Effect of farm machinery adoption on household income and food security: evidence from a nationwide household survey in India. Front Sustain Food Syst. 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.922038

Ji X, Wang K, Xu H, Li M (2021) Has digital financial inclusion narrowed the urban-rural income gap: the role of entrepreneurship in China. Sustainability 13 (15):Article 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158292

Ji Y, Gu T, Chen Y, Xu Z, Zhong F (2017) Agricultural scale management from the land level: based on the discussion of the relationship between circulation rent and land scale. J Manag World 7:65–73. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2017.07.006

Jiao M, Xu H (2022) How do collective operating construction land (COCL) transactions affect rural residents’ property income? Evidence from rural Deqing County, China. Land Use Policy 113:105897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105897

Kamble PA, Mehta A, Rani N (2023) Financial inclusion and digital financial literacy: do they matter for financial well-being? Soc Indic Res https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03264-w

Knickel K, Ashkenazy A, Chebach TC, Parrot N (2017) Agricultural modernization and sustainable agriculture: contradictions and complementarities. Int J Agric Sustain 15 (5):575–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2017.1373464

Leng Z, Wang Y, Hou X (2021) Structural and efficiency effects of land transfers on food planting: a comparative perspective on North and South of China. Sustainability 13 (6):Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063327

Li X, Guan R (2023) How does agricultural mechanization service affect agricultural green transformation in China? Int J Environ Res Public Health 20 (2):Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021655

Li X, Fu H (2023) Agricultural producer service subsidies and agricultural pollution: an approach based on endogenous agricultural pollution. Rev Dev Econ 27 (2):1177–1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12983

Li X, Mao H, Fang L (2024) The impact of rural human capital on household energy consumption structure: evidence from Shaanxi Province in China. Sustain Futures 8:100301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2024.100301

Li Y, Wang M, Liao G, Wang J (2022) Spatial spillover effect and threshold effect of digital financial inclusion on farmers’ income growth—based on provincial data of China. Sustainability 14(3):Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031838

Lin Q, Cheng Q, Zhong J, Lin W (2022) Can digital financial inclusion help reduce agricultural non-point source pollution?—An empirical analysis from China. Front Environ Sci 10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1074992

Liu C, Chen L, Li Z, Wu D (2023) The impact of digital financial inclusion and urbanization on agricultural mechanization: evidence from counties of China. PLoS One 18 (11):e0293910. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293910

Liu J, Fang Y, Wang G, Liu B, Wang R (2023) The aging of farmers and its challenges for labor-intensive agriculture in China: a perspective on farmland transfer plans for farmers’ retirement. J Rural Stud 100:103013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.103013

Liu T, He G, Turvey CG (2021) Inclusive finance, farm households entrepreneurship, and inclusive rural transformation in rural poverty-stricken areas in China. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 57 (7):1929–1958. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1694506

Liu Y, Zhou Y (2021) Reflections on China’s food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization. Land Use Policy 109:105699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105699

Liu Y, Liu C, Zhou M (2021) Does digital inclusive finance promote agricultural production for rural households in China? Research based on the Chinese family database (CFD). China Agric Econ Rev 13 (2):475–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-06-2020-0141

Liu Y, Deng Y, Peng B (2023) The impact of digital financial inclusion on green and low-carbon agricultural development. Agriculture 13 (9):Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13091748

Liu Y, Hu W, Jetté-Nantel S, Tian Z (2014) The influence of labor price change on agricultural machinery usage in Chinese agriculture. Can J Agric Econ 62 (2):219–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12024

Van Loon J, Woltering L, Krupnik TJ, Baudron F, Boa M, Govaerts B (2020) Scaling agricultural mechanization services in smallholder farming systems: case studies from sub-saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. Agric Syst 180:102792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102792

Lu H, Zhang P, Hu H, Xie H, Yu Z, Chen S (2019) Effect of the grain-growing purpose and farm size on the ability of stable land property rights to encourage farmers to apply organic fertilizers. J Environ Manag 251:109621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109621

Lu Q, Du X, Qiu H (2022) Adoption patterns and productivity impacts of agricultural mechanization services. Agric Econ 53 (5):826–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12737

Lu H, Huan H (2022). Does the transfer of agricultural labor reduce China’s grain output? A substitution perspective of chemical fertilizer and agricultural machinery. Front Environ Sci 10: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.961648

Luo J, Li B (2022) Impact of digital financial inclusion on consumption inequality in China. Soc Indic Res 163 (2):529–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02909-6

Ma J, Li Z (2021) Does digital financial inclusion affect agricultural eco-efficiency? A case study on China. Agronomy 11 (10):Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11101949

Ma J, Li G, Chen P, Li D (2023) How does digital financial inclusion affect farmers’ choice of agricultural mechanisation: evidence from China. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 0 (0):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2023.2295994

Mottaleb KA, Krupnik TJ, Erenstein O (2016) Factors associated with small-scale agricultural machinery adoption in Bangladesh: census findings. J Rural Stud 46:155–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.012

Mottaleb KA, Rahut DB, Ali A, Gérard B, Erenstein O (2017) Enhancing smallholder access to agricultural machinery services: lessons from Bangladesh. J Dev Stud 53 (9):1502–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1257116

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2023). Bulletin on the national grain production in 2023. https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202312/t20231221_1945708.html

Niu G, Jin X, Wang Q, Zhou Y (2022) Broadband infrastructure and digital financial inclusion in rural China. China Econ Rev 76:101853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101853

Qian H, Tao Y, Cao S, Cao Y (2020) Theoretical and empirical analysis on the development of digital finance and economic growth in China. J Quant Technol Econ 37 (6):26–46. https://doi.org/10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.2020.06.002

Qing C, Zhou W, Song J, Deng X, Xu D (2023a) Impact of outsourced machinery services on farmers’ green production behavior: evidence from Chinese rice farmers. J Environ Manag 327:116843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116843

Qiu H, Feng M, Chi Y, Luo M (2023) Agricultural machinery socialization service adoption, risks, and relative poverty of farmers. Agriculture 13 (9):Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13091787

Qiu T, Luo B (2021) Do small farms prefer agricultural mechanization services? Evidence from wheat production in China. Appl Econ 53 (26):2962–2973. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2020.1870656

Qiu T, Shi X, He Q, Luo B (2021) The paradox of developing agricultural mechanization services in China: supporting or kicking out smallholder farmers? China Econ Rev 69:101680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101680

Rahaman A, Kumari A, Zeng X-A, Khalifa I, Farooq MA, Singh N, Ali S, Alee M, Aadil RM (2021) The increasing hunger concern and current need in the development of sustainable food security in the developing countries. Trends Food Sci Technol 113:423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.04.048

Shen Y, Shi R, Yao L, Zhao M (2024) Perceived value, government regulations, and farmers’ agricultural green production technology adoption: evidence from China’s Yellow River Basin. Environ Manag 73 (3):509–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01893-y

Su L, Peng Y, Kong R, Chen Q (2021) Impact of E-commerce adoption on farmers’ participation in the digital financial market: evidence from rural China. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 16 (5):Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050081

Suri T, Bharadwaj P, Jack W (2021) Fintech and household resilience to shocks: evidence from digital loans in Kenya. J Dev Econ 153:102697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102697

Tamirat TW, Pedersen SM, Lind KM (2018) Farm and operator characteristics affecting adoption of precision agriculture in Denmark and Germany. Acta Agric Scand Sect B Soil Plant Sci 68 (4):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2017.1402949

Tao Z, Zhi Z, Shangkun L (2020) Digital economy, entrepreneurship, and high-quality economia development: empirical evidence from urban China. J Manag World 10 (36):65–76. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2020.0154

Tkach V, Medyukha E, Zemlyakova N, Pudeyan L, Chanturia K, Moskvitin E (2019) Digital management of financial condition of agricultural enterprises. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci 403 (1):012134. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/403/1/012134

Verkaart S, Munyua BG, Mausch K, Michler JD (2017) Welfare impacts of improved chickpea adoption: a pathway for rural development in Ethiopia? Food Policy 66:50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.11.007

Wan G, Hu X, Liu W (2021) China’s poverty reduction miracle and relative poverty: Focusing on the roles of growth and inequality. China Econ Rev 68:101643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101643

Wang J, Zhang S, Liu B, Zhang L (2023) Decision making with the use of digital inclusive financial systems by new agricultural management entities in Guangdong Province, China: a unified theory of acceptance and use of technology-based structural equation modeling analysis. Systems 11 (10):Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11100513

Wang S, Zhang W, Wang H, Wang J, Jiang M-J (2021) How does income inequality influence environmental regulation in the context of corruption? A panel threshold analysis based on chinese provincial data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (15):Article 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158050

Wang X, He G (2020) Digital financial inclusion and farmers’ vulnerability to poverty: evidence from rural China. Sustainability 12 (4):Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041668

Wang X, Fu Y (2021) Digital financial inclusion and vulnerability to poverty: evidence from Chinese rural households. China Agric Econ Rev 14 (1):64–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-08-2020-0189

Wang X, Zhang Z, Ge J (2018) The effects and efficiency of agricultural machinery purchase subsidies: from the perspective of incentive effect and crowding-out effect. China Rural Surv 02:60–74

Wang M, Song W, Qi X (2023) Digital inclusive finance, government intervention, and urban green technology innovation. Environ Sci Pollut Res https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-29395-8

Xia D, Kong C-L (2024) The impact of digital inclusive finance on rural revitalization: evidence from China. J Organ End User Comput 36 (1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.4018/JOEUC.337970

Xiao Y, Zhang Y, Wen C, He Q, Xia X (2022) Does digital financial inclusion narrow the urban-rural income gap? Evidence from prefecture-level cities in china. Transform Bus Econ 21 (2B):792–815

Xiaodong C, Yang L, Ke Z (2022) Research on the path of digital economy to improve China’s industrial chain resilience. Reform Econ Syst 01:95–102

Xu M, Chen C, Ahmed MA (2024) Market-oriented farmland transfer and outsourced machinery services: evidence from China. Econ Anal Policy 81:1214–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2024.02.014

Xu Q, Zhu P, Tang L (2022) Agricultural services: another way of farmland utilization and its effect on agricultural green total factor productivity in China. Land 11 (8):Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081170

Yamauchi F (2016) Rising real wages, mechanization and growing advantage of large farms: evidence from Indonesia. Food Policy 58:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.11.004

Yan G, He Y, Zhang X (2022) Can development of digital inclusive finance promote agricultural mechanization? - Based on the a perspective of the development of agricultural mechanical outsourcing service market. J Agrotech Econ 01:51–64. https://doi.org/10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2022.01.011

Yang J, Huang Z, Zhang X, Reardon T (2013) The rapid rise of cross-regional agricultural mechanization services in China. Am J Agric Econ 95 (5):1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat027

Yang Q, Jia J, Liu J, Xu Q (2023) How does the subsidy to the purchase of agricultural machinery and tools affect the overall grain production capacity? Based on the perspective of socialization services of agricultural machinery. J Manag World 39 (12):106–123. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2023.0147

Yang S, Zhang F (2023) The impact of agricultural machinery socialization services on the scale of land operation: evidence from rural China. Agriculture 13 (8):Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081594

Yang Y, Lin W (2021) Agricultural machinery purchase subsidy, agricultural machinery service, and farmers’ income. J Agrotechn Econ 9:16–35. https://doi.org/10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2021.09.002

Yang A, Yang M, Zhang F, Kassim AAM, Wang P (2024) Has digital financial inclusion curbed carbon emissions intensity? considering technological innovation and green consumption in China. J Knowl Econ https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01902-3

Zhang C, Liu Y, Pu Z (2023) How digital financial inclusion boosts tourism: evidence from chinese cities. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 18 (3):Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030082

Zhang H, Li Y, Sun H, Wang X (2023) How can digital financial inclusion promote high-quality agricultural development? The multiple-mediation model research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20 (4):Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043311

Zheng H, Ma W, Zhou X (2021) Renting-in cropland, machinery use intensity, and land productivity in rural China. Appl Econ 53 (47):5503–5517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1923642

Zhou J, Chen H, Bai Q, Liu L, Li G, Shen Q (2023) Can the integration of rural industries help strengthen China’s agricultural economic resilience? Agriculture 13 (9):Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13091813

Zhou L, Takeuchi H (2010) Informal lenders and rural finance in China: a report from the field. Mod China 36 (3):302–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700409360745

Zhou M, Zhang J, Huang L, Lu Q, Yuan H, Bao L (2024) Research on the spatio-temporal evolution and impact of China’s industrial green development from the perspective of digital economy—based on analysis of 279 cities in China. Environ Res Commun 6 (7):075034. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/ad578d

Zhou X, Ma W, Li G, Qiu H (2020) Farm machinery use and maize yields in China: an analysis accounting for selection bias and heterogeneity. Aust J Agric Resour Econ 64 (4):1282–1307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12395

Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Yan Z (2022) Will digital financial inclusion increase chinese farmers’ willingness to adopt agricultural technology? Agriculture 12 (10):Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12101514

Zhu Y, Deng J, Wang M, Tan Y, Yao W, Zhang Y (2022) Can agricultural productive services promote agricultural environmental efficiency in China? Int J Environ Res Public Health 19 (15):Article 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159339

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Special Funds for Fujian Provincial Social Science Research Base “Research Center on the Road of Rural Revitalization of Eastern Fujian Characteristics” (Min Social Science Regulation [2020] No. 1, Min Finance and Education Instruction [2021] No. 103); Special Funds for “Precision Poverty Alleviation and Anti-Return to Poverty Research Center” of New Type Think Tank of Fujian University Characteristics (Min Jiao Ke [2018] No. 50); Special Funds for Fujian Higher Education Institutions Science and Technology Innovation Team “Fujian Marine Economy Green Development Innovation Team” (Min Jiao Ke [2023] No.15); Special Funds for Fujian Key Think Tank Cultivation Unit “Research Center for High Quality Development of Marine Economy in Fujian Province, Ningde Normal University” (Min Zhi Ban [2023] No. 6); Ningde Teachers College Research and Development Funding Program: [2017FZ06, 2021FZ09, 2021FZ17, 2023FZ05, 2024FZ006]; The National Social Science Fund project (22CGL003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY: writing original draft, formal analysis, data curation; LC: writing review & editing; ZZ: methodology, writing review & editing, visualization; YW: writing review & editing, methodology, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not applicable as the study did not involve collecting data from human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Chen, L., Zhou, Z. et al. Digital financial inclusion and agricultural modernization development in China—a study based on the perspective of agricultural mechanization services. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 577 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04821-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04821-z