Abstract

Fictions with imaginary worlds such as Star Wars, Harry Potter, Game of Thrones or One Piece are achieving global success in industrialized societies. This paper investigates the historical trajectory and psychological underpinnings of this phenomenon. Study 1 (N = 51,169 novels and 50,928 movies) documents a clear increase in the prevalence and centrality of imaginary worlds from antiquity to the modern era. Study 2 demonstrates a historical shift toward imaginary worlds that are increasingly rich in detail, systematically structured, and internally plausible. Study 3 shows that economic development correlates with an increase in the popularity of imaginary worlds more than time does, suggesting that greater material security fosters curiosity and cultural engagement with cohesive imaginary worlds. This body of work illuminates an important aspect of modernity, namely the rise of imaginary worlds, and demonstrates that this could be explained as the results of the rise of curiosity among modern audiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, some of the most universally acclaimed and financially successful fictions are set within fabricated worlds, such as Star Wars, Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, and One Piece. These stories have achieved remarkable cross-cultural appeal, often leading in terms of box office receipts, book sales, and merchandise. Consider, for example, the universe of One Piece, crafted by Eiichiro Oda. This manga and anime series, which has sold over 490 million copies globally, navigates through the Grand Line—an oceanic world filled with imaginary islands. Similarly, the Star Wars saga, created by George Lucas, unfolds across a galaxy teeming with various planets—ranging from the desert wastelands of Tatooine to the forested expanse of Endor.

And this phenomenon extends beyond the blockbuster successes of a few franchises. In China, Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, a science fiction novel, has captivated millions and won the prestigious Hugo Award. In France, Jean-Philippe Jaworski’s critically acclaimed Gagner la guerre immerses readers in the Renaissance-inspired city-state of Ciudalia. Animated movies from Japan’s Studio Ghibli and America’s Disney frequently transport audiences to imaginary worlds (e.g., Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, Frozen, Moana). And recent television series, the popularity of which benefits from global streaming platforms, continue this trend of exploring non-existing environments (e.g., Stranger Things, The Expanse).

Why are imaginary worlds so successful in contemporary societies? Is this success recent? In literary history and cultural evolution, some scholars argue that the prominence and importance of imaginary worlds is a relatively recent trend globally (e.g., Besson 2015; Wolf 2013). But others might point out that imaginary worlds, from the countries visited by Ulysses in the Odyssey to the court of Avalon in the Arthurian romances to Thomas More’s Utopia, are as old as literature. One might thus ask whether there is really an increase of the imaginary world over time. And, if there is indeed a rise of imaginary worlds in history, this raises the question as to what contributed to the increasing success of imaginary worlds across different cultures. Put differently: why did imaginary worlds—with their dangerous monsters, exotic places, and marvelous cities—not appeal to ancient audiences, and emerge earlier in world literature?

The answers to such questions are not immediately evident. First, to this day, there is no empirical evidence for any trend concerning imaginary worlds. An exhaustive manual review and systematic annotation of 371 literary texts featuring imaginary worlds ranging from −750 to 1950, as listed by Wolf (see Methods below for more details about the sample and the annotation pipeline), reveals that imaginary worlds have most likely been a consistent feature since the inception of storytelling. More importantly, these early works were often enriched with maps, glossaries, bestiaries, and other paratextual devices, highlighting a long-standing appeal for detailed information about these settings (Fig. 1). This warrants us to carefully test any claim regarding trends in the prevalence and complexity of imaginary worlds over time.

From left to right and top to bottom: The first occurrence of a map of imaginary worlds in Wolf’s list, in Coropaedia by Caspar Stiblinus (1555); the first occurrence of a glossary in Wolf’s list, in The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins by Robert Paltock (1751; date of edition reviewed: 1783); first occurrence of a bestiary in Wolf’s list, in Nonsense songs by Edward Lear (1871); the map with the highest number of locations (~400) in A Father’s Memoirs of His Child by Thomas Williams Malkin (1806); a map of Janseina in Relation du pays de Janséine by Le Père Zacharie de Lisieux (1660); a map of the Underground in The Goddess of Atvatabar by William R. Bradshaw (1892).

First, this paper empirically investigates literary historians’ claim that imaginary worlds have seen an increase in prevalence and importance—key indicators of their cultural success. Second, we explore how imaginary worlds have changed across history. Finally, we explore predictions from behavioral ecology suggesting that curiosity—our proposed mechanism underpinning the human fascination for imaginary worlds—intensifies in more affluent environments. This approach aims to address why imaginary worlds become more successful with time, as human societies have become more affluent.

Note that, in this paper, we focus on written or recorded stories, such as literary works and films. This necessarily excludes an important part of popular literature, namely oral productions such as ballads, folktales, and epics—many of which were created to amuse and entertain. This omission reflects the practical constraints of our methodology rather than a theoretical choice. Future work would benefit from incorporating oral traditions where reliable datasets become available. Our work also excludes non-fictional narratives such as history, religion and myth. This is intended. These narratives are usually not considered as fiction by the population. We thus assumed that their cultural success is not based on the same factors. For instance, these narratives often rely on an audience’s belief in their truth and serve functions such as social control or practical teaching rather than entertainment.

Results

Study 1: Documenting the rise of imaginary worlds

This study tests whether there has really been an increase in both prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds in literature and cinema. Using comprehensive datasets, we analyzed global trends over an extensive temporal range, from ancient texts to contemporary productions. The literature dataset, derived from Wikidata and Wikipedia, includes 51,169 literary works, spanning from 700 BCE to 2015 CE, and including works from Arabic literature, Japanese literature and Chinese literature. The movie dataset, combining IMDb data and Wikipedia entries, encompasses 50,928 films from the dawn of cinema to the present day (see Methods below for more details).

To study the evolution of the prevalence of imaginary worlds, we first need to identify which literary works and movies are set in an imaginary world. We identify works set in imaginary worlds using speculative genres as proxies, such as fantasy and science fiction (see Methods below). This approach is supplemented, for movies, by a random forest algorithm which is trained on manual annotation and uses user-generated plot keywords for a more precise classification (out-of-bag error rate of 9.35%, see Methods below).

For literary works, we calculated the proportion of works per decade identified as speculative, adjusting for robustness by excluding decades with fewer than 10 works. The analysis spans from 550 BCE to 2020 CE. We observe a significant increase in the relative number of works set in imaginary worlds (p = 3 ×10−5; see Fig. 2A). The proportion of works identified as speculative rose from below 10% in early records to over 30% in recent decades, with a significant rise after the industrial revolution. This result was also robust against varying thresholds for the inclusion of decades (i.e., from 0 to 50; see Fig. 2D and Methods). This method is still highly sensitive to the availability of explicit genre labels, which varies across time. For instance, Science Fiction did not exist as a recognized category in antiquity, with the first occurrence in our dataset dating to 1889. While some speculative labels were used earlier—Fantasy, for example, first appears in Wikipedia with A True Story (170 CE)—their application was inconsistent. To circumvent this limitation, we supplement this approach with an alternative method to quantify the importance of imaginary worlds in literature (see below).

A Evolution of the relative number of literary works with a speculative genre in the world (N = 50,558 literary works), with a focus on post-1700 literary works. B Evolution of the relative number of movies with a speculative genre in the world (N = 49,566 movies). C Evolution of the relative number of movies that are set in an imaginary world, as assessed by a random forest algorithm (N = 8301 movies). D Sensitivity analysis for the evolution of the relative number of literary works with a speculative genre: the significance of the trend is independent of the cut-off of the minimum number of works per decade (see Methods).

In cinema, the analysis was conducted annually from the inception of film to the present, categorizing films based both on speculative genres and on the outcomes of the random forest algorithm. The results confirm a consistent rise in films depicting imaginary worlds (for both genres and random forest: p = 7.71 ×10−11 and 5.20 ×10−5 respectively; see Fig. 2B, C). The proportion of movies categorized in speculative genres (science fiction or fantasy) evolved from below 5% to almost 10%. The overarching trend is consistent: during the 20th century, the proportion of imaginary worlds in fictional narratives has at least doubled, in both literature and cinema.

To study the evolution of the importance of imaginary worlds within the stories, we used an automatic annotation method using Large Language Models (LLMs; see Method and Dubourg et al. 2024; for other applications, see Dubourg and Chambon 2025; Dubourg et al. in review), which quantified the amount of new, detailed information they provided about their imaginary settings. The annotation process, involving General Pretrained Transformer’s (GPT) extensive knowledge base, assigned scores reflecting the degree to which each world was central and novel within its narrative. LLMs have already shown significant promise in annotation tasks (Abdurahman et al. 2024; Brown et al. 2020; Ding et al. 2023; Grossmann et al. 2023), with accuracy exceeding that of other annotation methods (Bongini et al. 2023; Pei et al. 2023; Rathje et al. 2024; Gilardi et al. 2023), even in specialized domains (Fink et al. 2023; Savelka et al. 2023; Bongini et al. 2023).

We applied this method on all 6045 literary works anterior to 1950 CE in our dataset, and to a random selection of a little more than 1000 literary works from 1950 CE onwards (total N = 7132, spanning 4 millennia from 2400 BCE to 2020 CE; the greater temporal range compared to the previous study is due to the consideration of individual work, not averaged by decades with thresholds). Each literary work has been assigned an Imaginary World (IW) Score out of 10 (mean = 1.4, sd = 1.8, range = [0–8]) along with a justification from GPT. These annotations have been made accessible for public review on OSF. The low mean IW Score was expected, as many literary works are set in the real world. Note that the prompt, the dataset, the predictions, as well as the statistical plan were all pre-registered for this study.

We also pre-registered a set of external validity checks to ensure the accuracy of this automatic annotation method, comparing IW Scores between works classified within speculative genres and those not. Significant differences confirmed the method’s effectiveness, with speculative works scoring higher than non-speculative ones (t(479.21) = −34.1, p < 0.001; see Fig. 3A and Methods for similar results with specific genres). We also manually reviewed over 100 output justifications from GPT (see Methods for some examples and interpretation).

The results of the LLM annotations reveal a significant increase in the IW Scores across literary works over time (β > 0, p = 0.025; see Fig. 3B). This upward trend indicates a persistent rise in the richness and novelty of imaginary worlds portrayed in literature. The low effect size (β = 0.00008) was anticipated: first, the biases we noticed (see Methods) likely undermines this effect and, additionally, this effect reflects the incremental annual increase in the average IW Scores from −2400 to the present, on a scale from 0 to 10.

Our analyses converge and indicate an undeniable rise in both the prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds. The statistical results, robust across various analyses and methodologies, underscore the growing success of these imaginary worlds. This study is the first one to provide empirical evidence for such a trend at scale.

Study 2: Documenting the change of imaginary worlds

In this second study, we use the same LLM-based annotation method as Study 1 to automatically annotate several features of imaginary worlds (N = 371; compiled by Wolf, 2013; see Methods for details about the corpus and some qualitative observations of the texts) ranging from approximately 850 BCE (Homer’s The Odyssey) to 1950 CE (excluding some works from Wolf’s list due to, e.g., non-fictional content). We provide the full list of the 21 selected dimensions, definitions (as formulated in our GPT prompts), and references that motivated us to include such dimensions (see Table 1). These dimensions were inspired by the study of (1) fictional universes in literary theory (e.g., Besson 2015), (2) landscape preferences in environmental aesthetics (e.g., Kaplan 1992), and (3) curiosity or novelty-seeking behaviors in cognitive and behavioral sciences (e.g., Baranes et al. 2014).

Using the LLM-based annotation method, we rated all 371 stories set in imaginary worlds from Wolf’s list on each of the 21 dimensions identified, on a score from 0 to 10 (0 typically being the absence of the dimension and 10 the extreme importance or relevance of the dimension). We reviewed all the output justifications (see OSF for the entire list). Our initial step involved conducting several validity checks for the GPT annotations, notably against Wolf’s manual classification of imaginary worlds. We found strong alignment between the GPT-annotated characteristics and Wolf’s taxonomy for some dimensions (see Fig. 4A and Methods). We could not extend internal or external validation to all 21 dimensions due to the scale of the dataset and the use of fine-grained, novel constructs. For the remaining dimensions, we rely on the assumption that GPT’s accuracy in the tested dimensions applies similarly to the others, though future research will be needed to confirm this. These results should be viewed as an exploratory step, with further validations required to establish broader reliability.

A Example of validity check: graphical representation of GPT-annotated Sizes and Exploration for various types of imaginary worlds, as established by Wolf (2013). Our analysis reveals a congruence between the size classifications annotated by GPT and the expected hierarchy of Wolf’s categories. Specifically, the GPT-annotated Size of imaginary worlds exhibits a trend that aligns with intuitive size distinctions among the various world types—for instance, an island being typically smaller than a country, which in turn is smaller than a continent, and so forth. Conversely, Exploration was equally high across all types. B Visualization of the principal component analysis (PCA) on the variables contributing to the construction of imaginary worlds. C A scatter plot mapped according to their scores on Cohesion (Dimension 1) and Deviation (Dimension 2). We label a selected sample of imaginary worlds. D The weighted evolution of Cohesion and Deviation. E The comparison of Cohesion and Deviation before and after 1800. F Bias control, estimating how many works from pre-1800 distribution of Cohesion should be added to the post-1800 distribution of Cohesion for the statistical difference to disappear (for p being above 0.05). The blue line is the average of all simulations.

Then, we used Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to simplify the multidimensional data from GPT’s annotations, focusing on the two first principal components (PCs) that together captured nearly half of the variance (46%; Fig. 4B). The first PC seems to capture the extent to which worlds diverge from reality (we coin it ‘Deviation’). It is close to Wolf’s notion of invention, defined as “the degree to which default assumptions based on the Primary World (i.e., the real world) have been changed, regarding such things as geography, history, language, physics, biology, zoology, culture, custom, and so on” (Wolf, 2013). The second PC assesses the internal consistency and structural integrity of these worlds (‘Cohesion’). It is close to Wolf’s second notion of consistency, defined as “the degree to which world details are plausible, feasible, and without contradiction. This requires a careful integration of details and attention to the way everything is connected together.”

Importantly, by construction, these dimensions are independent. Worlds can score variably on each axis, leading to diverse classifications (Fig. 4C). For example, Alice in Wonderland (1865) is high in Deviation but low in Cohesion, showcasing its creative but logically inconsistent universe. In contrast, in The Archers (1950), Borsetshire scores low on Deviation but high in Cohesion, indicating a world closely mirroring real rural counties in England, with strong internal logic. Some worlds, like Tolkien’s Arda, achieve high scores on both dimensions, illustrating a universe that is both richly inventive and cohesively structured, potentially explaining its cultural success and scholarly recognition (Besson 2015).

Linear models applied to the data revealed that, while the novelty of the worlds (Deviation) remained stable (p = 0.25), their Cohesion significantly increased over time (β = 0.003, p < 0.001), suggesting a historical trend towards more intricate and well-structured imaginary worlds.

To ensure these trends were not artifacts of biased sampling or historical proliferation of literature, we implemented two robustness checks. First, we applied weighted linear modeling, which adjusts the influence of each imaginary world based on its temporal proximity, assuming a linear decrease in the proportion of worlds sampled over time (see Methods). This method helps correct for the potential overrepresentation of more recent worlds in the dataset. The weighted analysis confirmed our initial findings: Deviation remains stable over time (p = 0.65), while Cohesion significantly increases (β = 0.003, p < 1.65 × 10−5; Fig. 4D).

Second, we divided the imaginary worlds into two cohorts—before and after 1800 CE—to assess changes in Cohesion over time (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.001; Fig. 4E). Then, we performed 1000 counterfactual simulations to estimate the number of post-1800 works that would need to be “missed” by Wolf for the difference in Cohesion to dissipate (see Methods). The simulation suggests that for the observed increase in Cohesion post-1800 CE to be a result of biased sampling, Wolf would have needed to miss 332 imaginary worlds between 1800 CE and 1950 CE, assuming none were missed before 1800 CE (Fig. 4E). This scenario would imply a strong bias towards more Cohesive imaginary worlds in sampling recent works, an assumption that, while not impossible, appears unlikely given the selection criteria employed.

Both analyses confirmed that the observed increase in Cohesion was not an artifact of sampling bias. These results suggest a genuine evolution in the structural complexity and detail of imaginary worlds, indicating an increasing preference for more cohesive and elaborate narrative environments.

Study 3: Explaining the rise of structured worlds

Having established that imaginary worlds have become both more successful (Study 1) and more cohesive while maintaining their novelty (Study 2), we aim now at understanding why this trend persists. In a recent article, we proposed that imaginary worlds artificially activate the human preference for exploration—an evolved cognitive mechanism attuned to cues from information-rich new environments (such as perceptual or epistemic novelty), prompting directed exploration aimed at acquiring knowledge and reducing uncertainty (Dubourg & Baumard, 2022a). These inputs constitute the proper domain of the mechanism.

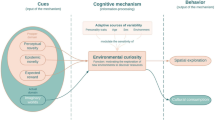

Imaginary worlds, as entirely novel fictional settings, fulfill the input conditions for the activation of this mechanism: they belong to the actual domain of the same mechanism (i.e., the domain of stimuli that do activate the mechanism, even if the latter has not evolved to detect and process it; see Sperber and Hirschfeld 2004). This is, in fact, very close to what Tolkien said when he stated that the appeal of his imaginary world stems from the “intrinsic feeling of reward” felt when “viewing far off an unvisited island or the towers of a distant city”. We therefore hypothesized that the factors influencing this mechanism of environmental curiosity also impact the desire to consume stories with imaginary worlds (see Fig. 5). In a recent empirical article, we provided evidence that the appeal for imaginary worlds rely on human curiosity and that the cultural preference for imaginary worlds is driven by individual variability in curiosity (Dubourg et al. 2023).

Proposed model of the computational architecture of environmental curiosity (in orange), with the actual domain of the cognitive mechanism (in green). From Dubourg et al. 2023.

But why, then, has the success of such worlds increased over time? A first hypothesis is that this is due to stimulus intensification. This theory has already been successfully applied to artistic and fictional productions (De Tiège et al. 2021; Dubourg et al. 2024a; Nettle 2005). For instance, superheroes exhibit enhanced shoulder-to-waist ratios (Burch and Johnsen 2020; Burch and Widman 2023), because of the pre-existing mechanism that favors strong allies (Sell et al. 2009; Singh 2021). Children’s toys and animated characters frequently feature disproportionately large eyes and foreheads (Hinde and Barden 1985), because of the pre-existing mechanism that favors faces with neotenous traits (i.e., ‘cute’ faces; Glocker et al. 2009a; Glocker et al. 2009b). And fictional monsters often display enhanced predatory features (Clasen 2017; Morin and Sobchuk 2023; Scalise Sugiyama 2006) because of the pre-existing mechanism that favors informational gains about deadly predators (Clinchy et al. 2013; Öhman 2009; Scrivner 2022).

This could explain why fictions are becoming more and more imaginary, and imaginary worlds more and more cohesive. Creators would progressively refine their craft just as humans refine any technology: they observe that some ingredient work better, and they increase the proportion of these ingredient. For instance, developers noticed that players respond positively to clear reward systems and incremental challenges. In consequences, game designers introduced “progression systems” like leveling up, achievements, and loot boxes; early print ads focused on product descriptions, but over time, advertisers refined their strategies to emphasize storytelling, social proof, and lifestyle association; and in the 19th century, serialized novels in magazines gained popularity as they kept readers engaged with cliffhangers.

Just like for any stimuli in fictions, as creators understand they can exaggerate them and as they refine their craft, they slowly converge toward the “sweet spot” that maximizes audience engagement. A recent study revealed that the foreheads of teddy bears have progressively grown larger over time, increasingly mimicking the facial features of babies and more effectively engaging our cognitive mechanisms for perceiving cuteness (Borredon et al. 2025). Similarly, monsters in fiction, such as Godzilla, have become progressively larger and more imposing, amplifying their threatening features to better tap into our cognitive sensitivity to predatory cues (Sobchuk 2019). Such stimuli intensification, furthermore, could be amplified in larger and more competitive markets. As the number of producers grows, competition drives them to refine and exaggerate stimuli that appeal most strongly to cognitive preferences (Hills 2019).

Another hypothesis is that the rise of imaginary worlds corresponds to a shift in people’s level of curiosity. Curiosity, like other personality traits, is indeed modulated by the environment (Dubourg and Baumand 2024). In contexts where the ecology is affluent and safe, the costs associated with exploration (e.g., opportunity costs) decrease, while the evolutionary benefits (e.g., informational gains) increase (Boon-Falleur et al. 2024). As societies globally have been experiencing rising levels of affluence and safety due to technological advancements, curiosity and Openness to experience have tended to increase in the general population (Baumard 2019; Inglehart 2018). We thus hypothesize that stories, shaped by creators to engage cognitive preferences—whether consciously or not—should change in response to an increase in curiosity, and include more and more elements that trigger human curiosity (Dubourg and Baumard 2022b).

We evaluate which hypothesis is more strongly supported by our data, by comparing whether proxies of affluence or time alone best predict the increasing success and importance of imaginary worlds. We emphasize that this is not a direct test of the stimulus intensity hypothesis but rather an exploratory analysis to understand which variable better accounts for the observed trends. We use a dual-model approach in our analysis, applying linear regression models to examine the effects of time and GDP—a proxy for societal affluence—on the prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds and compare their goodness of fit assessed through the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

For the increase in prevalence of imaginary worlds (using speculative genres as a proxy), the model with time as a predictor had shown a significant positive effect of time in Study 1 (AIC = −30.42). When GDP was used as a predictor, it too showed significant effects (p < 0.001, AIC = −33.12), with the GDP model providing a better fit (ΔAIC = 2.7), indicating that GDP is a stronger predictor of the prevalence of imaginary worlds in literature.

For the increase in importance and novelty of imaginary worlds (using GPT annotation from Study 1; this prediction and analysis were pre-registered), when averaged across decades, the time variable was not a significant predictor (p = 0.89, AIC = 33.86), while GDP was, with a better goodness of fit (p < 0.014, AIC = 26.74, ΔAIC = 7.12). Even after adjusting for the quantity of literary works per decade, GDP remained a significant and stronger predictor (p = 0.0018, AIC = 22.82, ΔAIC = 11.96).

Both analyses support the hypothesis that the increasing prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds in literature are more closely associated with economic development than with the mere passage of time. While not causal in nature, such results support the hypothesis of a cultural shift where rising affluence enhances curiosity and engagement with novel and complex fictional environments.

Discussion

We have established several key findings: the proportion of literary works and films set in imaginary worlds has increased, more than doubling in proportion in the past century across both mediums; the amount of new information depicted in these imaginary worlds within literature has grown, making these worlds more central in the narratives; although imaginary worlds have consistently diverged from the real world, their internal structure and coherence have become more pronounced over time; and, finally, the increase in prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds are better explained by a proxy of affluence than by time alone.

These quantitative analyses are in line with qualitative observations. First, such worlds were not predominant in earlier times: we observed an increase in the proportion of imaginary worlds in the overall literary and cinematic productions. As Jenkins (2006) wrote: “More and more, storytelling has become the art of world-building, as artists create compelling environments that cannot be fully explored or exhausted within a single work or even a single medium”. More specifically, the recent cultural success of franchised fiction (i.e., a series of different stories set in the same world, often spanning across multiple media) suggests a growing audience preference for stories that offer ongoing exploration, which should require high tolerance and even appreciation of ambiguity (Hsiung et al. 2023; Metcalfe et al. 2021).

Second, and more importantly, none or very few of ancient imaginary worlds had the expansive depth and breadth of more recent worlds like Middle-Earth from The Lord of the Rings. As GPT reports when annotating The Odyssey for instance, The Cyclops Islands “are described with a certain level of detail, but they are not as thoroughly structured as other imaginary worlds might be. Homer provides information about the inhabitants, particularly the Cyclops Polyphemus, and some aspects of the environment, such as the cave where Odysseus and his men are trapped. However, the broader organization of the islands, their geography, and their societal structures are not deeply explored.”

Now, why did it take until the last century for such rich and structured imaginary worlds to invade the landscape of popular fictional stories? It does not seem to be a matter of ability; as their works attest, ancient authors had the same potential to create large and structured imaginary words as modern writers. One may argue that societal and technological advancements allowed for more and more detailed world-building, but this does not hold when we consider that inventing an imaginary world requires no more than imagination and a medium to record it.

We hypothesized that the explanation lies not is not in the ability of the creators or the tools at their disposal, but in the preferences of the audience. It is not that authors could not create such worlds earlier, but that there was not a substantial audience demand or appreciation for them until more recent times (for a similar idea applied to romances, see Zhong et al. 2023; Baumard et al. 2022). In this paper, we have provided some evidence that the effect of phenotypic plasticity, whereby curiosity changes according to the affluence of the local environment, translates in the cultural domain: cultural artifacts that tap into this mechanism of curiosity become more successful as human societies become more affluent.

We also want to emphasize that we do believe the stimulus intensification hypothesis offers insights into the evolving form and appeal of imaginary worlds. This is often described in psychology as reaching cognitive sweet spots, the most exaggerated stimuli that remains within the boundaries of what is cognitively manageable or pleasurable for observers (Dubourg and Baumard 2022a; e.g., Dunbar 2017). However, this hypothesis only explains the direction of the stimulus exaggeration, not the timing. A cognitive sweet spot can typically be achieved through trial and error quite rapidly, within a generation or two. Therefore, this hypothesis cannot alone explain why the prevalence and importance of imaginary worlds remained stable for centuries up until the sharp increase following the Industrial Revolution. We argue that our ecology-driven hypothesis, whereby consumers’ preferences change according to their local ecologies, could be the missing causal factor here. Framed in a way that is consistent with both frameworks, our study suggests that sweet spots (or ‘cognitive attractor’ in cultural attraction theory) continuously move, as human psychology flexibly adapts to new ecological conditions.

Such results should be complemented. Firstly, future research should study how the production of imaginary worlds in specific cultural areas follows the affluence levels of these specific areas. In other words, as we hypothesize that cues in the immediate ecology modulates people’s level of curiosity, our work is limited in its conclusion as it only relies on the aggregate measure at the world level. More work is needed both at a more local scale and in non-Western societies—which may be underrepresented in our sample (see Methods; see Dubourg et al., in review). For instance, the peak in the IW Score for the 4th century (Fig. 1F) is primarily due to the contribution of some Indian texts. Of the 38 texts referenced in that century, 7 scored above 4 (contributing to the high average IW Scores for this century, at 1.9). Among these 7 high-scoring texts, 5 are of Indian origin (e.g., Manimekalai, a Tamil epic). This result does support our hypothesis: India was the country with the highest economic prosperity at that time (Maddison 2007).

Second, in this article, we only provided evidence for the effect of resources on some proxies of cultural success of imaginary worlds. But we have not provided direct evidence that the link between the two (i.e., the mediator) is curiosity itself. As we settled in our theoretical article (Dubourg and Baumard 2022a), other plausible explanations tie economic developments to shifts in cultural representations. One candidate mechanism is morality. More particularly, puritanical morality often condemns harmless pleasurable activities, such as glutonery or masturbation, because indulging in such activities make one appear, or indeed become, a less reliable cooperative partner (Fitouchi et al. 2023). Consuming stories set in imaginary worlds could be perceived, especially by puritanical standards, as one such “frivolous” activity, potentially indicative of low levels of self-control. Yet, as resource affluence increases, interpersonal trust grows (Guillou et al. 2021; Safra et al. 2020), reducing the need to moralize and condemn such activities. This decline in puritanism could therefore, in turn, contribute to the rise of imaginary worlds in literature.

In closing, note that we are not yet satisfied with our working definition of curiosity. While in another paper we have provided evidence that, on average, people who are more curious enjoy more imaginary worlds, the proportion of variance in the enjoyment of imaginary worlds explained by people’s curiosity is not high (Dubourg et al. 2023). We believe that this is, in large part, because curiosity is not unitary. People can in fact be curious about very different things (Kashdan et al. 2018; Kobayashi et al. 2019), such as others’ morality (Wylie and Gantman 2023), potential threats (Scrivner 2022), counterfactuals (Fitzgibbon and Murayama, 2022), or explanations (Liquin and Lombrozo 2020), effectively leading to different ‘ingredients’ in fictional stories (Dubourg et al. 2024b). There seems to be a common mechanism behind all these kinds of curiosity, since there is some shared variance in information-seeking at the interindividual level (Kelly and Sharot 2021; Silvia and Christensen 2020): people who are more curious about one thing tend to be more curious about other things, on average (Dubourg & Baumard, 2024). Yet, it seems that the information being sought or processed is more or less intriguing or interesting, to a particular individual, depending on what it is about.

We discovered in Study 2 that the extent to which imaginary worlds deviate from the real world does not change over time, on average. Since we expect, in general, stimuli exaggeration to be enhanced in ecological contexts that make the targeted mechanism more sensitive, this finding pushes us to reconsider our initial hypothesis that imaginary worlds are appealing mainly because they are novel (Dubourg and Baumard 2022a). As we have shown, what appears to be increasing, alongside the popularity of imaginary worlds, is the degree to which these worlds are structured, that is, the degree to which these worlds can be systematized by readers and viewers (as in user-generated fandoms, i.e., online encyclopedia about imaginary worlds). What we come to postulate here is another kind of curiosity for specific information about one’s environment: information that fits well some ‘bigger picture’, slowly building a consistent ‘system’. Some have subsumed this motivation under the concept of ‘structure-seeking tendencies’, linking them to a desire for agency (Landau et al. 2015; Metcalfe et al. 2021).

This idea is in line with previous experimental results where people’s systemizing quotient (i.e., the motivation to build, predict, and apply rules to a system; Baron-Cohen 2003; Nettle 2007) was strongly correlated to their exploratory preferences (β = 0.49), and was correlated to the reported enjoyment of imaginary worlds in the same order of magnitude as exploratory preferences (β = 0.24 and 0.26, respectively; Dubourg et al. 2023; see Browning and Veit 2022; on autism and exploration, see Poli et al. 2023; on autism and patterns, see Crespi 2021). Our findings therefore support the idea that engaging with and enjoying imaginary worlds is a by-product of a cognitive mechanism that motivates humans (and some more than others) to learn the structure of a given ‘system’. For this mechanism, it appears, the more structured the system, the better. This can suggest that the function of this mechanism is to enhance predictive power in natural ecosystems or social networks—the more structured the system, the more predictable it is. The function of this mechanism might also be to enhance the controllability of such systems—the more structured the system, the more controllable it is (for a distinction between predictability and controllability, see Ligneul 2021).

As we hypothesized, this is the same kind of curiosity which seems satisfied by the release of a work of fiction taking place in an already existing fictional world, extending it. This mechanism is perhaps even more apparent and intuitive when it is deceived: fans of imaginary worlds are known to track, resent, and try to solve inconsistencies in such worlds (e.g., McGonagall appearing in Hogwarts, in Rowling’s movie Crimes of Grindelwald, way before she is said to arrive in Hogwarts in the book; see Besson 2015). To get the intuition of what is rewarding for this system-based curiosity: at a much lower-level, it should explain the satisfaction derived from fitting two puzzle pieces together. If this is the case, this form of curiosity, which we postulate is at the basis of the success of imaginary worlds, could also explain the increasing success of spinoffs and franchises.

Method

Qualitative study

Corpus

For this qualitative study, we needed a corpus of stories with imaginary worlds. We chose to work with the sample established by Wolf (2013), with almost 1500 imaginary worlds referenced. Of course, this is not an exhaustive list, as the author points out: “This list of imaginary worlds, while broadly inclusive, is still far from complete and is only a sampling of worlds, chosen either for their size, scale, degree of subcreation, complexity, popularity, fame, historical significance, or uniqueness, to give an overview of the history of imaginary worlds.” Wolf’s list skews toward imaginary worlds that are particularly notable or influential. This fits our study’s focus on tracking the development of key features within these worlds. For instance, the presence of maps in early literary works would be a standout characteristic, making them more likely to be included in the list. Note that Wolf’s bias towards selecting the most prominent imaginary worlds may overestimate the presence of paratextual features like maps in earlier works, since such features would be more exceptional in the past. This bias likely provides, as in the previous study, a stronger test for our hypothesis: if despite this potential overrepresentation we still observe an increase in these features over time, it reinforces the argument for an historical trend towards more explorable imaginary worlds (H2). As in this study we are interested in earlier trends, we focused on imaginary worlds published before 1950. We therefore annotated 601 literary works, ranging from 850 BCE (approximate dating of Homer’s The Odyssey) to 1950 CE.

Manual annotation method

As we had to investigate the content of each of the works of fiction featuring imaginary worlds referenced by Wolf, we turned first to two online platforms: the Internet Archive, the world’s largest and oldest web archive, and Project Gutenberg, one of the oldest online initiatives aiming for widespread distribution of eBooks. If the full text of the original targeted literary work was not present on either platform, we turned to Google search engine and looked for PDFs of the literary works (adding to the search keywords ‘filetype:pdf’). If not available on the Internet, we turned to local libraries (Paris, France), by systematically looking for the physical copies of the books in both Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s (BnF) online catalog and Paris’ online library network. For each of the works referenced, we kept looking for older editions until we found either a copy of the original version or the oldest copy available. When different from the original date, we noted the edition date of the copy we used, for further analysis.

During the data collection process, we excluded some of Wolf’s listed works, for three main reasons: (1) the work was not fictional (e.g., Plato’s Republic); (2) the work was fictional but not a book (e.g., Asimov’s Blind Alley is a short story, initially published in a magazine); (3) the work was in a language we could not handle (let us clarify that familiarity with the language was essential to rapidly pinpoint the presence of the features we wanted to annotate; see below). In all, we excluded 150 imaginary worlds referenced by Wolf. Moreover, during the annotation process, 80 works could not be found either on the Internet or in accessible Parisian libraries. We therefore annotated 371 literary works. Among these, 303 works were found and analyzed online, 68 were found and analyzed with hard copies at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

For each of these works, we used a page-by-page browsing technique to look for the paratextual elements we had decided to annotate. This technique is efficient for this annotation task, as what we want to annotate is the presence and characteristics of highly visible elements in books, such as maps. Here is the full list of annotated materials:

-

(1)

The presence and the number of maps. We counted as a map any piece of illustration that provided geographical information specifically on how the imaginary world is structured. We hence excluded any maps providing information solely on the real world, as it is. If there was a map, we counted the number of locations present on each map. We then counted the presence or absence of water (i.e., seas, oceans, rivers), mountain(s), forest(s), desert(s), island(s), archipelagos, compass, and cues suggesting that the map was only a segment of the full imaginary world (e.g., arrows towards the exterior of the map, continents whose borders are suggested to be outside the map).

-

(2)

The presence of a glossary for a fictional language. If there was a glossary, we also determined an approximation of the number of invented words in each glossary. For glossaries below 4 pages, we manually counted them. For glossaries above 4 pages, we manually counted the number of words in one page and multiplied by the number of remaining pages of the glossary.

-

(3)

The presence of a bestiary. If there was a bestiary, we also manually counted the amount of fantastic beasts featured.

-

(4)

The presence of illustrations. Given that maps and bestiaries were counted as separate variables, we excluded those from our illustration variable.

-

(5)

The presence of footnotes.

-

(6)

The presence of non-narrative texts (e.g., encyclopedia entries, appendices, fictional documents).

In this first phase of the study, our objective was to determine if there has been a historical trend toward increasing use of paratextual devices to help enrich such imaginary worlds (e.g., maps, glossaries, bestiaries). These features were chosen for investigation because (1) they are readily identifiable through distant reading techniques, allowing us to efficiently browse through all the texts from Wolf’s list and manually annotate specific elements without needing to read each text in its entirety (Moretti 2013), and (2) they were the subject of a prediction in our earlier research, which posited an increase in their use over time (Dubourg and Baumard 2023). Such a trend would support our hypothesis that human curiosity for novel information is the reason why imaginary worlds are so appealing—with these devices serving as a means to efficiently present more information in a condensed form.

This qualitative analysis revealed a significant use of paratextual devices across the examined sample of stories set in imaginary worlds, with varying prevalence: non-narrative texts (e.g., encyclopedia entries, appendices) were found in 20.8% of works, footnotes in 11.1%, maps in 4.5%, chronologies in 2.2%, character lists in 2%, glossaries in 0.8%, bestiaries in 0.6%, and genealogies in 0.3%. These features seem more common in speculative fiction compared to non-speculative literature. We also qualitatively observed a historical shift from blending real-world elements with imaginary ones, to exclusively imaginary elements in such paratextual devices. For example, early maps may mix real and imaginary geographies, but later works tended to feature wholly invented worlds.

We also computed finer-grained features for each paratextual device and were able to qualitatively monitor the evolution of such features in time: as time goes by, maps feature more and more locations, chronologies more and more dates, and character lists more and more characters. For maps, we also assessed the presence of six different ecological features in each map (i.e., water bodies, mountains, forests, deserts, islands, and archipelagos). Each feature added to the map contributed to a cumulative ‘ecological diversity’ score for each map. This scoring system revealed an increase in ecological richness in the imaginary worlds depicted.

While this study did not empirically test specific predictions due to the limited availability and challenging acquisition of relevant data, these trends seem to have persisted in contemporary works of fiction since 1950. For instance, the One Piece manga series features detailed maps that guide readers through the expansive world of the Grand Line. The Attack on Titan anime uses informational freeze frames that resemble pages from a military manual, providing background on its lore. And the Witcher series integrates bestiaries and character diaries, offering insights into the creatures encountered by the character, and Netflix even produced a series of YouTube videos titled ‘Bestiaries,’ which delve into the details of the monsters featured in each episode.

Study 1

Datasets

The Literature dataset is a compilation of data derived from Wikidata and Wikipedia. We extracted literary works using a SPARQL query, systematically retrieving details such as title, main subject, genre, country of origin, language, English Wikipedia webpage, and author information. Additionally, we have access to the Wikipedia summary and the full Wikipedia page for each work. In total, the dataset includes 51,169 literary works, spanning a temporal range from −700 to 2015, and originating from various countries. With its decentralized contributor base, Wikipedia offers a diverse representation of literary works. Its self-correcting mechanisms and vast contributor base make it less likely for biases to persist, especially biases that would be inconsistently distributed across time (see Piscopo and Simperl 2019; Shenoy et al. 2022; for examples of the use of this dataset in large-scale study: Beytía and Schobin 2018; Fraiberger et al. 2018; Laouenan et al. 2022; Lucchini et al. 2019; Schich et al. 2014).

The Movie dataset is a fusion of multiple sources, primarily the IMDb dataset and scrapped Wikipedia data. The IMDb component provides metadata for 50,928 movies, encompassing various details from title to box office earnings. The Wikipedia component offers additional insights through Wikipedia pages and plot summaries. This dataset captures cinematic productions from the dawn of cinema to the present day, spanning various countries. While this dataset seems almost exhaustive, there might exist a slight bias towards US productions. This can be attributed to the dominance of platforms like IMDb and Wikipedia in the West. However, given the sheer volume and diversity of the data, this dataset remains a robust foundation for our analyses.

All entries were included in Study 1 without filtering. Year and genre information were available for all IMDb items, while Wikidata items lacking genre were still included in calculations as part of the total dataset.

Automatic detection

To discern whether a story, be it a literary work or a movie, is set in an imaginary world, we need a clear variable indicating the presence or absence of this specific feature. The challenge lies in the fact that there is no direct indicator for this in most datasets. As a solution, we turned to genres as a proxy. Specifically, we focused on speculative genres, which are genres of fiction that speculate about worlds that are unlike the real world, featuring elements such as magic, futuristic settings, or fantastical creatures.

While this is a useful proxy, it is worth noting that it is not a perfect overlap with our variable of interest: not all speculative fiction feature an imaginary world in the sense of a physical environment that doesn’t exist and is different from real-world environments. For instance, stories that feature fantastic creatures might still be set in familiar real-world settings. A fiction like Spider-Man, for instance, introduces extraordinary powers and beings, yet the backdrop is a city that mirrors our own, like New York City.

For our literary dataset from Wikidata, which contains a high number of different genres and combinations thereof, we identified works that fall under various speculative sub-genres: fantastic, utopian, dystopian, alternate (as in alternate history or alternate reality), apocalyptic, superhero, and supernatural. We selected all literary works that had at least one of these genres in their genre list. For our movie dataset from IMDb, which categorizes movies into one or several of 23 genres (with many possible combinations), the process was streamlined. We focused on the two speculative genres in this list: fantasy and science fiction. Given the vast number of genre combinations in IMDb, we chose movies that had at least one genre among science fiction and fantasy in their genre list.

For our movie dataset, we capitalized on an additional measure to discern the presence of imaginary worlds more specifically, using the detailed metadata of keywords available in IMDb. These keywords, essentially user-generated descriptors associated with movies, offer insight into the content and themes of the films. This measure was specifically tailored for movies because, unlike our Literature dataset, the Movie dataset provides access to these plot keywords for 9,425 movies (the smaller sample size therefore reflects filtering for movies with this specific user-generated metadata, required for the algorithm). Such metadata is conspicuously absent for Wikipedia, which restricts us from applying a similar classification method for literary works. This method was developed for another article (Dubourg et al. 2023), but we will provide a brief overview here.

We started by manually coding 385 movies, randomly selected from the IMDb dataset, to determine if they were set in an imaginary world. The primary criterion for this classification was the mention of a non-existent location in the IMDb movie summary. With no mention of any location, the movie was tagged as an existing location (under the assumption that summaries almost always specify the imaginary location when the story is set in one). With the mention of a futuristic world, it was tagged as an imaginary location (under the assumption that such locations don’t exist as such in the real world of the audience). Using this manual coding, we trained a random forest classification algorithm on plot keywords. This algorithm was then extrapolated to a broader sample of 9424 movies. Our algorithm achieved an out-of-bag error rate of 9.35%. It is worth noting that while the algorithm adeptly identified movies not set in imaginary worlds, it exhibited a slight conservative bias in flagging those that were, leading to a modest underestimation. Further validation demonstrated that movies pinpointed by our algorithm as set in imaginary worlds were also more likely to be categorized under the science fiction and fantasy genres in IMDb (see Dubourg et al. 2023).

Automatic annotation

Finally, for the automatic annotation method by GPT, we address the challenge of measuring the novelty and size of imaginary worlds in narrative fiction in a large dataset. We use an automatic annotation method that uses Large Language Models (LLMs), leveraging the capabilities of GPT through its API. This approach lies in the ability to systematically query GPT to annotate literary works within our databases by providing the titles and the names of the authors, when available. This method capitalizes on the vast repository of textual data on which GPT has been trained, including descriptions, summaries, and analyses of literary works. In other words, we harness GPT’s trained ability to retrieve and synthesize relevant information about these works (Chang et al. 2023; Underwood 2023). Our method follows a structured process outlined by Dubourg and colleagues (Dubourg et al. 2024b). By iteratively prompting GPT with a prompt, we leverage the model’s extensive knowledge base to assess the size and novelty of imaginary worlds in literature. The prompt, validity checks, and analyses were all pre-registered. Here is the prompt:

“Rate the unfamiliar aspects of the imagined world from 0 (familiar or known) to 10 (entirely novel and unknown), considering the amount of invented information. Provide a very brief justification. You must write the score after / SCORE = / at the end, with no text nor symbol after. If you don’t know the work, score NA. The work is: [Title].”

We applied the Welch Two Sample t-test to evaluate the difference in IW Scores between speculative and non-speculative works. Our analysis revealed a higher IW Score for speculative fiction works compared to non-speculative works (t(479.21) = −34.1, p < 0.001). To ensure robustness, we extended our validity check across different genres within the speculative category: science fiction genre had a higher IW Score than non-science fiction (t(267.86) = −34.81, p < 0.001). Fantasy genre had a higher IW Score compared to non-fantasy (t(142.69)= −18.84, p < 0.001). Finally, the horror genre also had a higher IW Score than non-horror (t(44.41)= −5.86, p < 0.001). Conversely, to validate that the genres traditionally not associated with detailed imaginary worlds aligned with our expectations, we analyzed the non-fiction genres. Non-fiction scored lower (t(158.43) = 10.11, p < 0.001). On the whole, these findings confirm the methodology’s effectiveness.

To further validate that the IW Score accurately measures the richness and unfamiliarity of imaginary worlds, we conducted a manual review of select outputs from the GPT annotations, which include a justification for each assigned IW Score. Here is the justification for Alice in Wonderland (1865):

“Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass present a world that is a mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar. The characters are anthropomorphic animals and objects, which are familiar concepts, but they behave in ways that are unexpected and strange. The rules of the world are also constantly shifting and unpredictable, which adds to the unfamiliarity. However, the setting is based on a typical Victorian garden and household, which is a familiar environment. / SCORE = 7 /”

Here is the justification for The Isle of the Torturers by Clark Ashton Smith (1933), one of the eleven literary works with the maximum IW Score (i.e., 8/10):

“The Isle of the Torturers by Clark Ashton Smith is a part of the Zothique cycle, a series of fantasy stories set in a dying Earth. The world of Zothique is filled with strange and often horrific creatures, magic, and civilizations that are vastly different from our own. The Isle of the Torturers itself is a place of sadistic pleasure and pain, where the inhabitants delight in the suffering of others. This world is quite unfamiliar and filled with invented information. / SCORE = 8 /”

We identified two main issues. The first one is that GPT’s annotations sometimes seem to be based on the novelty of the imaginary worlds compared to previous imaginary worlds, vs. the novelty of the imaginary worlds compared to the real world (e.g., “In the Land of Twilight by Astrid Lindgren is a children’s book that takes place in a magical world where the boundary between dreams and reality is blurred. The world is filled with fairies, gnomes, and other magical creatures. However, the concept of a magical world where dreams and reality intersect is not entirely new in literature.”). This distinction is crucial. Our aim is not to evaluate the innovation of imaginary worlds within the historical context of literature (something that has been done, e.g., for cinematic productions; Dubourg et al. 2023; Luan and Kim 2022). Here, we wanted to measure the extent of the gap between the imaginary world and the real world.

The other problem is that GPT seems to sometimes annotate according to the perspective of a modern reader, vs. the intended original audience of the work (e.g., “Antigone by Sophocles is a classic Greek tragedy that takes place in a world familiar to its original audience, with its setting in ancient Thebes and its use of well-known mythological characters and themes. However, for a modern reader unfamiliar with Greek mythology and ancient Greek society, some aspects of the world may seem unfamiliar, such as the importance of burial rites, the role of the gods, and the concept of fate.”). Yet, we wanted to measure the degree of unfamiliarity for the audience the work was built for. This approach stems from the hypothesis that entertainment products are shaped to align with the preferences of their surrounding audience (Dubourg and Baumard 2022a), so that such works are reflections of the audience’s preferences within their specific temporal and spatial contexts (i.e., ‘cognitive fossils’; Baumard et al. 2023).

However, these two biases in the annotation process actually work against our hypothesis of increasing IW Scores over time: the first one likely gives higher IW Scores to ancient fictional worlds than it should, just because they are far away from modern readers; and the second one likely gives lower IW Scores to recent imaginary worlds than it should, just because they are compared with a higher number of past imaginary worlds—making it difficult to innovate. Therefore, this test can be seen as a highly conservative one: if our prediction is confirmed under these conditions, it suggests the underlying trend is robust. Note that we believe these two issues can be solved with prompt engineering, through the addition of new specifications, but since the prompt and analyses were pre-registered, we decided to proceed despite these biases. Modifications to address these problems will be implemented in our subsequent study.

Statistical analysis

We undertook four distinct statistical analyses, each corresponding to a specific variable: (1) the presence of imaginary worlds in literary works as determined by speculative genres; (2) the presence of imaginary worlds in movies as determined by the fantasy and science fiction genres; (3) the presence of imaginary worlds in movies as determined by the random-forest algorithm; (4) the importance of imaginary worlds in literature as determined by GPT.

For literary works, we computed the number of works for each decade present in our dataset, and then the number of these works that were set in imaginary worlds. This allowed us to calculate the relative share of imaginary worlds by decade, which is the proportion of literary works set in imaginary worlds compared to the total number of works for that decade. To ensure the robustness of our results, we excluded decades where fewer than 10 literary works were referenced. Despite this restriction, our analysis retained a good temporal depth, capturing the proportion of imaginary worlds from the year −550 to 2020. We also checked that our analysis was not dependent upon this arbitrary cut-off (see Results). Note that we include all works in the analysis, regardless of whether they have a genre label (55.6% of literary works lacked genre). We also replicated our analysis excluding works without a genre and found similar results.

For movies, our approach was more granular, given the richer dataset. We computed the data annually, rather than by decade. This involved computing the total number of movies per year, distinguishing between those that are set in imaginary worlds from those that are not. This process was replicated for both our proxies: genres and the random-forest classification. Given the volume of data, there was no need to set a threshold and exclude specific years. We ended up with the proportion of movies set in imaginary worlds for each year from 1927 to nowadays, for the two different variables.

Sensitivity analysis

For the analysis of literary works, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using 50 different cut-offs, varying the minimum number of literary works per decade from 1 to 50. This approach was aimed at assessing the robustness of our findings against the volume of data per decade. Consistently across all cut-offs, the linear models indicated a significant positive trend of time on the prevalence of imaginary worlds, with all p values below the 0.05 threshold, and predominantly below the 0.001 threshold. Notably, as the cut-off increased, thereby reducing the number of decades and works included in the analysis, we observed an improvement in the explanatory power of our models, as evidenced by increased R2 values. A juncture was observed at a cut-off of 39, beyond which the models demonstrated stronger results, characterized by higher R2 and smaller p values. This phenomenon is caused by the exclusion, after this specific cut-off, of very ancient decades (e.g., 200 CE) that, along with more recent decades, introduced considerable variability and data gaps into the analysis, thereby affecting the robustness of the statistical models. By applying a threshold above 39, the dataset became more homogeneous, encompassing only works from after 1200 CE. This sensitivity check reinforces the evidence in favor of an increasing depiction of imaginary worlds in literature over time.

Study 2

Automatic annotation method

We used the data as in the Qualitative Study (see Manual Annotation method for the data) and the same method as in Study 1, with one prompt for each dimension (see Table 1). The prompts included the definition in Table 1 with some more specifications for the LLM. For instance, for novelty, the prompt was:

Novelty is defined as the extent of difference between the imaginary world and the real world as experienced by the targeted audience. Rate the novelty of the imaginary world on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents an imaginary world that closely mirrors the real-world of the targeted audience without significant deviations, and 10 indicates an imaginary world that is vastly different from their real world. Ignore comparisons with other imaginary worlds.

All the prompts were structured like that (with 0 and 10 being the extreme on a continuum from absence to importance), except the prompt for the Description dimensions:

Description is defined as the proportion of the literary text dedicated to detailing the environment of the imaginary world. Estimate the ratio of text that focuses on the description of the environment, out of 10, where 0 represents a narrative with no description of the imaginary environment (0% of description), and 10 indicates a narrative entirely devoted to the description of the environment (100% of description). Focus exclusively on the ratio of descriptive text related to the environment within the overall narrative.

Validity check

We conducted several validity checks to validate the accuracy of GPT’s annotations on the characteristics of imaginary worlds depicted in literary works. First, a manual review of GPT’s outputs was performed to ensure that it accurately comprehended each defined attribute (refer to Supplementary Materials for comprehensive list of these outputs).

Second, for a more robust validity check, we used Wolf’s manual annotation schema (2013) as a benchmark. Wolf’s classification notably includes the categorization of imaginary worlds into distinct types—Island, City, Kingdom, Land, Country, Place, Continent, World, Underground, Earth, Moon, Planet, and Universe. This taxonomy is predicated on the implicit hierarchy of the size associated with each type of world—ranging from the relatively diminutive scale of an island to the expansive scope of a universe.

Our analysis reveals a congruence between the size classifications annotated by GPT and the expected hierarchy of Wolf’s categories. Specifically, the GPT-annotated Size of imaginary worlds exhibits a trend that aligns with intuitive size distinctions among the various world types—for instance, an island being typically smaller than a country, which in turn is smaller than a continent, and so forth. Conversely, Exploration was equally high across all types (see Fig. 3A). This observation suggests some uniformity in the extent of exploration undertaken by characters across various types of imaginary worlds, independent of their size. More importantly here, it reinforces GPT’s capability to discern and accurately annotate nuanced aspects of imaginary worlds within literary texts.

Finally, an examination of the pairwise correlations between all annotated variables further validated this automatic annotation process. Notably, there was a significant inverse correlation between Novelty—defined as the magnitude of divergence between the characteristics of a given imaginary world and the real world—and Realism, which we conceptualize as the extent to which an imaginary world mirrors the environments of the real world. This negative correlation is perfectly in line with our expectation. These results support our hypothesis that advanced language models like GPT possess a capacity for nuanced comprehension and annotation of literary content.

Weighted models

A potential concern in our data analysis is the historical over-representation of earlier imaginary worlds. In earlier periods, the production of works featuring imaginary worlds was relatively limited, and most major texts from these times are well-documented and widely recognized. As a result, Wolf’s database likely includes a near-comprehensive sample of these works. In contrast, literary production expanded dramatically after the Industrial Revolution, generating an overwhelming volume of works. This surge makes it increasingly difficult to achieve exhaustive coverage of modern imaginary worlds, resulting in a lower sampling proportion in more recent periods. We therefore assume that the proportion of imaginary worlds sampled decreases over time, an assumption based on the methodology used by Wolf and the historical growth in literary production.

To address this challenge, we implemented a weighted linear modeling approach, assuming a linear decline in the proportion of sampled imaginary worlds from 100% in 1250 (as if Wolf had found all imaginary worlds from this period, as there are few of them) to 10% by 1950 (as if Wolf had referenced only 10% of imaginary worlds produced in 1950, which is highly unlikely as Wolf’s list, until the mid-20th century, seems quasi-exhaustive). This method gives greater analytical weight to older worlds, mitigating potential biases from an expanding pool of stories. The weighted analysis confirmed our initial findings: Deviation remains stable over time (p = 0.65), while Cohesion significantly increases (β = 0.003, p < 0.001). This suggests that, despite a constant level of novelty in the creation of imaginary worlds, there has been a trend towards more cohesive (i.e., consistent and structured) imaginary worlds.

Robustness check

There is another potential bias in our previous analysis, linked to the sampling of imaginary worlds. This potential bias emerges from the premise that as literature and cinema have proliferated, especially after the onset of the Industrial Revolution, so too have the depictions of imaginary worlds. Consequently, Wolf’s sampling could inadvertently favor more and more cohesive worlds simply because there are more and more imaginary worlds being produced. This introduces a non-uniform bias across time, complicating the assessment of temporal trends in the characteristics of imaginary worlds.

To gauge the extent of this potential bias, we developed a specific methodology. First, we divided the imaginary worlds into two cohorts based on a temporal threshold: those created before 1800 and those created after. This threshold aligns with both the Industrial Revolution and the boom in the number of imaginary worlds in literature observed in Study 1. Employing the Wilcoxon test—a non-parametric method—we reaffirmed that worlds post-1800 exhibit higher Cohesion levels (but do not significantly differ in Deviation) when compared to their pre-1800 counterparts.

Now, if one were to argue that this observation stems from biased sampling favoring more cohesive imaginary worlds in more recent times, then one essentially posits that the distributions of Cohesion for both cohorts should, in theory, align closely. Under this skepticism, the pre-1800 cohort, presumably sampled more exhaustively, should serve as the benchmark distribution for evaluating Cohesion.

We performed a simulation to estimate the number of post-1800 works that would need to be “missed” by Wolf for the observed difference in Cohesion to dissipate. Using the pre-1800 distribution of Cohesion as a benchmark, we iteratively simulated additional post-1800 entries by sampling from this earlier distribution, gradually increasing the number of simulated works in the post-1800 cohort. At each step, we recalculated the difference in Cohesion between the two cohorts using a non-parametric Wilcoxon test to determine the point at which the observed difference would lose statistical significance (p > 0.05). This simulation was replicated 1000 times, allowing us to model the distribution of outcomes and quantify the number of missing post-1800 works required to eliminate the observed disparity. The full R script used for this analysis is available in OSF.

The curve summarizes, across simulations, the quantity of overlooked post-1800 works necessary for our observed Cohesion disparity to be attributable solely to this bias.

Study 3

Dataset

To test our prediction in study 3, we use the same datasets as Study 1 supplemented by the world GDP data sourced from the New Maddison Project Database and the World Bank (2015). GDP serves as a proxy for societal affluence and safety. Two concerns must be addressed. One concern is inequality. A rising world GDP might not be evenly distributed across all societies, and across all strata of societies. Yet, it is essential to note that substantial GDP growth, especially as seen in the last centuries, has generally led to improvements in living standards across the board, even if the benefits are unequally distributed. The fact that societies become richer and more unequal at the same time is not paradoxical. The second potential limitation is the subjective perception of affluence. Not everyone might consciously perceive the security and prosperity of their environment. Yet, our theory does not imply that people have a conscious accurate estimation of the characteristics of their local environments in their minds, for such characteristics to impact their preferences at a nonconscious level. What’s more, individuals in economically developed societies do tend to report feeling more secure, on average (Kendall et al. 2019; Inglehart 2018).

Statistical analysis

We saw that two explanations could fit our previous analyses: the increasing prevalence of imaginary worlds in literature might be explained by (1) a psychological shift toward more exploration in audiences (i.e., our proposed hypothesis) or (2) time (because, e.g., producers would somehow get progressively better at world-building).

To have a first approximation of which explanation fits best our data, we conducted a comparative analysis using two linear regression models. The first model is the same one as in the previous study, investigating the relationship between the proportion of literary works set in imaginary worlds for each decade and the passage of time, represented by the decade itself. The second model investigated the relationship between the proportion of literary works set in imaginary worlds for each decade and the world’s GDP for that respective decade. We then used AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) to compare the goodness of fit of both statistical models. A lower value indicates a better-fitting model. A difference in AIC values (ΔAIC) greater than 2 is generally considered evidence of a meaningful difference in model fit.

This paradigm is not causal: it cannot aim to prove that rising GDP causes the rise of imaginary worlds. Such a causal link would require experimental evidence. However, what this study can show is the validity of the Ever-Present Feasibility Argument. If time turns out to be a weaker predictor than environmental characteristics, such as affluence here, it would lend weight to the idea that creators have always had the capability to craft imaginary worlds. It would be consistent with our hypothesis that ecological factors (in our hypothesis, affluence) impacts some underlying factor (in our hypothesis, curiosity), which in turn makes imaginary worlds more appealing in stories.

Sensitivity analysis

We filtered the datasets so that we take into account only the decades for which we have more than 10 literary works, like in the previous study. For the GPT annotation of importance and novelty of imaginary worlds, we end up with 17 decades for which we have an estimation of the world’s GDP (N = 2,582 literary works from 0 to 2020). In the model with time as the predictor variable, the effect of time was not significant (p = 0.89, AIC = 33.86). In the second model, with world’s GDP as the predictor variable, the effect of GDP was significant (p < 0.014, R2 = 0.30, AIC = 26.74). When comparing the goodness of fit of the two models using the AIC, the second model (GDP as a predictor) had a lower AIC value than the first model (time as a predictor), with ΔAIC = 7.12. GDP appears to be a stronger predictor based on the AIC values. While this was not pre-registered, we also checked whether adding the total number of literary works per decade as a variable in the model (i.e., controlling for the quantity of literary works) changed this finding. It didn’t: time in the first model is still not significant (p = 0.60), GDP in the second model is still significant (p = 0.0018), and ΔAIC is still superior to 2 (AICTime Model = 34.78; AICGDP Model = 22.82; ΔAIC = 11.96). We performed the analysis again after removing two outliers (i.e., 0 and 1000, keeping decades after 1500). Here, time in the first model turned out to be significant (p = 0.022, AIC = 26.40), GDP too (p < 0.001, AIC = 15.67) but AIC still favors the GDP model (ΔAIC = 10.73).

Data availability

References

Abdurahman S, Atari M, Karimi-Malekabadi F, Xue MJ, Trager J, Park PS, Golazizian P, Omrani A, Dehghani M (2024) Perils and opportunities in using large language models in psychological research. PNAS Nexus 3(7):245. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae245

Atran S (1998) Folk biology and the anthropology of science: Cognitive universals and cultural particulars. Behav Brain Sci 21(4):547–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X98001277

Banerjee K, Haque OS, Spelke ES (2013) Melting Lizards and Crying Mailboxes: Children’s Preferential Recall of Minimally Counterintuitive Concepts. Cogn Sci 37(7):1251–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12037

Baranes AF, Oudeyer P-Y, Gottlieb J (2014) The effects of task difficulty, novelty and the size of the search space on intrinsically motivated exploration. Front Neurosci 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00317

Baron-Cohen S (2003) The essential difference: The truth about the male and female brain. Basic Books New York

Baumard N (2019) Psychological origins of the Industrial Revolution. Behav Brain Sci 42:e189. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1800211X

Baumard N, Huillery E, Zabro L (2022) The cultural evolution of love in history. Nat Hum Behav 6(4):506–522

Baumard N, Safra L, Martins M de JD, Chevallier C (2023) Cognitive fossils: Using cultural artifacts to reconstruct psychological changes throughout history. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 28(2):172–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.10.001

Bermejo-Berros J, Lopez-Diez J, Gil Martínez MA (2022) Inducing narrative tension in the viewer through suspense, surprise, and curiosity. Poetics 93:101664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2022.101664

Besson A (2015) Constellations: Des mondes fictionnels dans l’imaginaire contemporain. CNRS éditions