Abstract

In this paper, we present a brief critical analysis of the data, methodology, and results of the most recent publication on the computational phylogeny of the Indo-European family (Heggarty et al. 2023), comparing them to previous efforts in this area carried out by (roughly) the same team of scholars (informally designated as the “New Zealand school”), as well as concurrent research by scholars belonging to the “Moscow school” of historical linguistics. We show that the general quality of the lexical data used as the basis for classification has significantly improved from earlier studies, reflecting a more careful curation process on the part of qualified historical linguists involved in the project; however, there remain serious issues when it comes to marking cognation between different characters, such as failure (in many cases) to distinguish between true cognacy and areal diffusion and the inability to take into account the influence of the so-called derivational drift (independent morphological formations from the same root in languages belonging to different branches). Considering that both the topological features of the resulting consensus tree and the established datings contradict historical evidence in several major aspects, these shortcomings may partially be responsible for the results. Our principal conclusion is that the correlation between the number of included languages and the size of the list may simply be insufficient for a guaranteed robust topology; either the list should be drastically expanded (not a realistic option for various practical reasons) or the number of compared taxa be reduced, possibly by means of using intermediate reconstructions for ancestral stages instead of multiple languages (the principle advocated by the Moscow school).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent publication by Heggarty et al. (2023) represents (at least) the third version of the Indo-European phylogeny published up to now by the interdisciplinary team whose key figures have been Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson. Their previous two publications (Gray and Atkinson, 2003; Bouckaert et al. 2012) have received considerable media attention, but also have been the subject of rather heavy criticism from Indo-Europeanists and general linguists for the inferior quality of their lexical data and unconvincing results as to their tree topology and datings (e.g. Anthony, 2013; Mallory, 2013; Pereltsvaig and Lewis, 2015; Kassian, 2023, etc., as well as various conference talks and blog posts by the abovementioned and other scholars).

The latest version, however, is significantly different from previous ones, as it involves the research of a much larger group of scholars (including some very prominent specialists in comparative Indo-European linguistics) and the production of a new massive digital resource for Indo-European basic lexicon (the IE-CoR database), based upon allegedly more detailed and rigorous standards of notation and analysis than ever before. The research has already garnered a significant amount of public attentionFootnote 1, creating the impression that the authors may have finally come up with the “gold standard” version of the internal classification and linguistic dating of the Indo-European family, as well as the territorial localization of the Proto-Indo-European homeland.

While there is no doubt whatsoever that the study is the product of serious and detailed scholarly research, it is also clear that, in order for its results to be accepted (or rejected) as the new default paradigm for Indo-European studies, it needs to undergo many rounds of serious evaluation from scholars in the field, preferably in the form of open public discussion. We offer this paper as one of the (hopefully, many to come) attempts at a critical evaluation of some of the new features introduced in the team’s third paper, concluding with our general opinion on whether its publication is sufficient to finally claim a definitive answer to some of the most well-known problems of classifying, dating, and localizing Indo-European.

Heggarty et al. propose a lexicostatistical tree-form classification of the Indo-European languages and claim that their findings chronologically support the Anatolian homeland for the first break-up of IE into the Anatolian and non-Anatolian branches and a subsequent steppe homeland for some of the intermediate ancestral states postdating the split of Indo-European (“Germanic-Italic-Celtic and possibly Baltic-Slavic”).

-

The date of the first break-up is 4740–7610 BC (95% probability), median 6120 BC.

-

The date of the [Balto-Slavic, [Italic, [Celtic, Germanic]]] break-up is 3040‒5940 BC (95% probability), median 4470 BC. It may be remarked that only the 95% HPD interval makes historical sense under the Bayesian approach, while the median/mean value should be referred to with caution. Surprisingly, throughout the paper, Heggarty et al. prefer to operate with the median values (which are, of course, more suitable and interpretable for scientific journalists and general readers).

The approach chosen by the authors is rather traditional for the field, without any substantial innovations. The standard dataset comprises 161 languages (incl. 52 non-modern languages) multiplied by 170 concepts and subjected to Bayesian inference analysis (BEAST software). The tree was chronologically calibrated with the help of 52 non-modern languages.

Our general impression can be preliminarily summarized as follows: on one hand, the new lexical database, IE-CoR, which was essentially compiled along the same theoretical and methodological lines that had been described and adopted in research papers published by scholars of the so-called Moscow School (see the list of references in section 2), is unquestionably a step in the right direction: the number of detected errors is relatively modest (and, of course, some mistakes are always inevitable in such a large-scale project). On the contrary, the obtained tree classification is not only statistically weak, but also runs contrary to solidly established knowledge in some important points. Thus, it can hardly serve as a firm basis for further research.

Dataset (IE-CoR)

The new dataset, named “IE-CoR”, consists of 170-item wordlists for 161 lects.Footnote 2 The overall lexicographic quality of IE-CoR is quite high; without a doubt, this is a great step forward for Gray & Atkinson’s team when compared to their previous projects (Gray and Atkinson, 2003; Bouckaert et al. 2012).

The natural reason for this improvement is that IE-CoR was prepared by an international team comprised of more than 80 linguists — experts in various IE groups and languages who have been working on it for four years. It may be noted that the project rather closely reflects the methodology that has, for almost 15 years, been advocated by the Moscow school of historical linguistics, including some of the key principles laid down by Kassian et al. (2010), later adopted in the Global Lexicostatistical DatabaseFootnote 3 and in such publications as Starostin, 2010; Starostin, 2013; Kassian, 2015; Kassian et al. 2015; Kassian, 2017; Kassian and Testelets, 2017; Kassian, Starostin et al. 2021; Egorov et al. 2022, and others. These include the following key moments of IE-CoR, whose systematic application leads to a significant boost in quality for the resulting dataset:

-

Introduction of explicit semantic specification of the concepts and diagnostic contexts;Footnote 4

-

all the slots are filled with neutral and most commonly used words, excluding usage of “parasitic” synonyms;

-

authoritative dictionaries and grammars are used (instead of anonymous Swadesh wordlists from Wikipedia, as in Bouckaert et al. 2012);

-

the involved forms are linked to the corresponding entries of online dictionaries (if available, e.g., Latin forms are linked to Lewis & Short’s Latin Dictionary).

Some of these principles, of course, go all the way back to the beginning of lexicostatistics (cf., e.g., Swadesh, 1955, 122: “for each test item the common, everyday equivalent is listed for each language”), but we are not really aware of their cohesive formulation in practical terms prior to the above-listed works by the Moscow team. However, the only straightforward reference to those works can be found in Heggarty et al.’s online supplement (p. 29), where the authors, without any additional comments or explanations, make a rather dubious claim that “IE-CoR protocols and meaning definitions differ radically” from those by Kassian et al. (2010). It would certainly be instructive to understand better what the authors mean by “radical” difference in this particular case.

Heggarty et al. also try to offer at least one original criterion for selecting the basic words for the given concepts: morphological simplicity vs. complexity (Suppl. p. 33). According to Heggarty et al., a morphologically simpler word normally has the selective advantage over a morphologically complex word. This criterion does not seem particularly reasonable; why should more default words for the given concepts necessarily have simpler morphology than less default words? While this might possibly be an echo of our own criterion of morphological primacy (Kassian et al. 2015, 305), it should be noted that we introduced it strictly for the purposes of semantic reconstruction and compilation of wordlists reconstructed for proto-languages, but there was never any intention to apply it to synchronic wordlists. Anyway, it is hardly an accident that Heggarty et al. could not provide a single proper example where the morphological simplicity criterion would actually work. Within all of Heggarty et al.’s pairs that allegedly have to do with this principle — Eng. full vs. filled, old vs. aged, black vs. blackened, Spanish pez vs. pescado, seco vs. secado — the first (morphologically simpler) item can be easily chosen according to other criteria (such as, e.g., frequency of usage) and does not demand any additional justification on the basis of morphology.

There are, however, two other conceptual ideas that were relatively recently introduced by our team but are ignored in IE-CoR:

-

1.

The IE-CoR authors adhere to the traditional and outdated root cognacy approach (Eng. wind = Russian veter) and ignore the recently discussed problem of derivational drift (Chang et al. 2015), even though derivational drift elimination (Eng. wind ≠ Russian veter) improves the tree topology and makes the tree more robust (Kassian, Zhivlov et al. 2021; Egorov et al. 2022).

-

2.

The IE-CoR authors mark loanwords in a rather mechanical way, ignoring internal semantic developments, which is unjustified (Starostin, 2013, 135; Kassian, 2017, 225). E.g., Modern Greek puˈli (πουλί) ‘bird’ is marked as a loan in IE-CoR. This form originates from late Ancient Greek πουλλίον, a diminutive of που̃λλος ‘chicken’. The latter was indeed borrowed from Latin pullus ‘young (of animals); chick, chicken’, but the meaning shift ‘chicken’ > ‘bird (in general)’ is an internal Greek development; therefore, Modern Greek pulˈi ‘bird’ should be treated as an internal replacement rather than replacement through borrowing from an extraneous source.

There are several other, more minor, elements which are also missing from IE-CoR, but should be recommended for such a database, as they have proven quite useful in the context of similar research by the Moscow school.

-

1.

More attention should be paid to etymological analysis of the involved forms to better discriminate between etymological cognates and loanwords (see below for a regrettable situation with Tsakonian Greek and Kashmiri).

-

2.

Individual languages lack a list of sources used for wordlist compilation, i.e., it is unclear which dictionaries and grammars have been used.

-

3.

Individual forms lack references to sources (it may be unclear where exactly the form has been taken from).

-

4.

Comments on individual forms are too short, e.g., if the paradigm is suppletive, it should be explicated how the roots are distributed.Footnote 5

-

5.

Forms lack morphemic division (affixes should be separated from the root).

-

6.

In their current struggle with quasi-synonyms (“consistency in number of lexemes per meaning, per language: only 1”, Suppl. p. 28), the authors go to the other extreme. For instance, the suppletive opposition between imperfective and perfective stems in verbal paradigms is relatively common cross-linguistically. The most reasonable solution would seem to take both suppletive stems as synonyms. But in IE-CoR, normally only one verbal stem, either imperfective or perfective, is picked up. As a result, the slot COME, for instance, is filled with the perfective prʲijˈtʲi for Russian (imperfective prʲixodʲitʲ is ignored),Footnote 6 but with the imperfective paˈriu for Tsakonian Greek (perfect/aorist ekan- is ignored).Footnote 7 This results in an unwarranted inconsistency.

Relying on our own expertise, we have closely checked five out of 161 IE-CoR wordlists, ca. 100 concepts in each (more precisely, the intersecting parts of Heggarty et al.’s 170-item list of concepts and the 110-item list used by the Moscow school): Bulgarian, Hittite (extinct), Gothic (extinct), Tsakonian Greek, Kashmiri. In general, the results of the examination were positive.

Standard Bulgarian

Ca. 100 out of 170 concepts have been checked, no errors found; an excellent resultFootnote 8.

Hittite

Ca. 100 out of 170 concepts have been checked. The result is acceptable (although it seems that the author of the list is not a Hittitologist)Footnote 9. The following errors can be noted:

-

1.

BIRD u̯attai- is a possible candidate, but not obligatory.

-

2.

CHEST is empty. Actually takk-ani- is a reliable candidate.

-

3.

DOG kuu̯an-/kun-. Actually, still not attested.

-

4.

FLY (v.) pattai-/patti- — not a basic verb for this meaning.

-

5.

NEAR & SHORT *maninku(u̯a)-. The asterisk is unnecessary, the stem maninkuu̯ant- ‘short’ and its form maninkuu̯an ‘near’ are reliably attested.

-

6.

NECK is empty. Actually kuwatt-ar ‘neck/nape of the neck, scruff/top of shoulders/mainstay, support’ is a reliable candidate.

-

7.

RED mida- ~ midi- ~ mitta- is a possible candidate, but not obligatory.

-

8.

SAY tē-. This is indeed one of the basic verbs for ‘to say (that)’ in Old Hittite. The second equally frequently used verb mema- ‘to say (that)’ should be added as a full synonym. Old Hittite was documented at the moment when the old verb tē- was being superseded by the innovative mema-.

-

9.

SEED u̯a(ru)u̯alan-: first, this is a typo for u̯ar(ru)u̯alan-, second, it seems to be unattested in the botanical sense.

-

10.

SKIN miluli- ~ maluli- is a possible candidate, but not obligatory.

-

11.

STONE peru(na)-. Actually the Hittite word for ‘stone’ is still not known. peru(na)- means ‘rock (i.e., cliff); boulder’. Possibly, the authors misinterpreted the American English gloss ‘rock’.

-

12.

WOMAN *kuu̯an-. Actually, still not attested.

Gothic

Ca. 100 out of 170 concepts have been checked. Although this is one of the worst results in all our check-ups, it still does not invalidate the wordlist in general. The result shows that the list is slightly biased toward the “etymological” side of things, i.e. an equivalent with transparent semantic cognates in other Germanic languages is occasionally preferred to a synonym that finds more support within the Gothic corpus itself (based on frequency analysis or comparison with the Greek originals of the Germanic translations)Footnote 10.

-

1.

DIE gaswiltan. The synonym gadauþnan should most certainly be used as well, as the two are occasionally interchangeable, and we have no clue as to which one was the more neutral equivalent during the creation of Ulfilas’ Bible.

-

2.

EAT itan. Not only should the innovative verb matjan be at least included as a synonym, but it is highly likely, based on an analysis of contexts, that itan was already a stylistically marked term in Gothic (it is used rarely and mostly in pejorative contexts).

-

3.

GO gaggan. No mention of the more frequently encountered ga-leiþan in the same meaning, which is actually a better candidate, since its meaning is always that of a verb of motion, whereas gaggan is more commonly used in Gothic to denote the secondary abstract meaning ‘be going to (do something)’.

-

4.

KILL dauþjan. This word is only encountered once in the entire corpus; the most common and neutral equivalent for this meaning is the innovative us-qiman.

-

5.

MAN guma. Of the three possible candidates for this slot (guma, manna, wair), for some reason, the least frequent (only three examples in the corpus) and the most questionable has been included.

-

6.

SEED atisk. A rather harsh mistake; this word, encountered only twice (in nearly identical contexts), is commonly analyzed as “sown grainfield” (Lehmann, 1986, 45). A more correct equivalent, albeit also only encountered once in the corpus, would be fraiw.

-

7.

WORM waurms. Another mistake that was possibly triggered by etymological considerations: the word waurms in Gothic translates to Greek ophis ‘snake’. A more correct equivalent would be the word maþa, translating Greek skōlēx ‘worm’.

The next two wordlists, Tsakonian Greek and Kashmiri, mostly suffer not from lexicographic errors, but from inappropriate etymological analysis: a large amount of loanwords has escaped detection, making the lects in question attracted to the corresponding dominating languages in the outcome tree.

Peloponnese Tsakonian Greek

Modern Tsakonian dialects are the descendants of the poorly attested Doric variety of Ancient Greek. Tsakonian has been heavily influenced by the part of vernacular standard Greek (initially Attic-based koine, further Medieval Greek and then Demotic Greek) for millennia; these contacts have been drastically intensified in the 20th and 21st centuries. Today, Tsakonian vocabulary is loaded with vernacular Greek loans of various chronological layers. Some of these loans are hidden and hard to detect, others are more transparently identified based on various phonological criteria (Pernot, 1934; Costakis, 1951)Footnote 11.

Since we can trace the development of (Attic) Greek vocabulary for at least two and a half thousand years, a strong indicator of “Pan-Greek” intrusions in Tsakonian is lexical replacements, which take place in vernacular Greek in the Middle Ages or later and recurrently appear in Tsakonian.

Ca. 100 out of 170 concepts have been checked, no serious lexicographic errors have been found. From the lexicographic point of view, this is indeed a high-quality wordlist. The systematic problem is that none of the Tsakonian forms in IE-CoR is marked as a vernacular Greek loan, although actually the number of borrowings from vernacular Greek is high, e.g.:

-

1.

BONE ˈko̞kale̞ 〈κόκαλε〉, a Medieval or later innovation,

-

2.

CLOUD ˈsiɣno̞fo̞ 〈σύγνoφο〉, a Medieval or later innovation,

-

3.

EAT tʃʰu 〈τσ̌ου〉, a Medieval innovation,

-

4.

FISH ˈpsaʒi 〈ψάζ̌ι〉, a Medieval innovation,

-

5.

NAIL ˈɲixi 〈νύχι〉 with Medieval i for 〈υ〉,

-

6.

and so on.

This makes the IE-CoR Tsakonian wordlist, at least in the way it has been presented, basically useless for phylogenetic purposes.

Kashmiri

The IE-CoR Kashmiri list is based on data from a native speaker of the Kamraaz dialect (northern part of the Kashmir valley)Footnote 12. Since this variety lacks comprehensive dictionaries and corpora, it is difficult to check how well the list was compiled. Comparison with Kogan’s (2016) 100-item wordlist of the Srinagar dialect (on which the literary language is based), compiled from lexicographic and field sources, reveals ca. 15 discrepancies. Some of them are connected with recent borrowings from Persian (the Kamraaz list offers inherited words for ‘bird’, ‘heart’, where Srinagar has Persian loans; conversely, the Srinagar list has inherited words for ‘breast’, ‘earth’, ‘neck’, which are superseded with Persian forms in Kamraaz). In other cases, the discrepancies could reflect real lexicostatistical divergence between the dialects or hidden loanwords from other donor languages.

The problem with the IE-CoR Kashmiri list is that a substantial number of Kashmiri forms likely borrowed from Indo-Aryan languages were marked as inherited; in order to distinguish between the two, one should be guided by detailed descriptions of the peculiarities of Kashmiri historical phonology, such as presented in recent works by Kogan (2005; 2016). Ca. 100 out of 170 concepts have been checked, the following cases of undetected borrowings can be noted:

-

1.

FLY woḍon. Corresponds to the prefixed Sanskrit stem uḍ-ḍīy-ate~uḍ-ḍay-ate ‘to fly up’ (Vedic √day-i) and its continuants in modern Indo-Aryan with the meaning ‘to fly’. Pace IE-CoR, most likely not an etymological cognate of Indo-Aryan forms, but an Indo-Aryan loanword, since this complex stem is widely attested in modern Indo-Aryan languages, but (practically?) not represented in the rest of Dardic. The inherited Kashmiri word for ‘to fly’ is documented in Kogan’s Srinagar list: wupʰ-.

-

2.

HEAD kallə. Pace IE-CoR, it cannot directly correspond to Vedic kapā́la- for phonetic reasons. No doubt, a borrowing from Persian kala ‘head’. The inherited Kashmiri word for ‘head’ is documented in Kogan’s Srinagar list: hiːr.

-

3.

MOUNTAIN pahaːṛ. Corresponds to modern Indo-Aryan forms for ‘mountain’, which originate from virtual *pāhāḍa-. Pace IE-CoR, not an etymological cognate of Indo-Aryan forms, but a recent borrowing from Urdu pahaːṛ ‘mountain’. Two inherited Kashmiri words for ‘mountain’ are documented in Kogan’s Srinagar list: baːl, sangur.

-

4.

STAND kʰaṛa. Corresponds to modern Indo-Aryan complex verbs ‘to stand’ which originate from virtual *kʰaḍa- ‘upright, erect’. Pace IE-CoR, not an etymological cognate of Indo-Aryan forms, but a recent borrowing from Urdu kʰaṛā honā ‘to stand’. The inherited Kashmiri verb for ‘to stand’ is documented in Kogan’s Srinagar list: wotʰ-.

-

5.

NIGHT raːtʰ. Pace IE-CoR, it cannot directly correspond to Vedic rā́trī- and its modern Indo-Aryan cognates (all meaning ‘night’) for phonetic reasons (Kogan, 2011, 40; Kogan, 2016, 91–92). Thus, the Kashmiri word is a borrowing from an Indo-Aryan source.

-

6.

ROUND gɔːl. Corresponds to Sanskrit gola- ‘ball, round object’ and its cognates in modern Indo-Aryan with the meaning ‘round’ (ultimately from Dravidian; in IE-CoR, recognized as an ancient borrowing into a proto-language). Pace IE-CoR, most likely not an etymological cognate of Indo-Aryan forms, but an Indo-Aryan loanword, since this word is widely attested in modern Indo-Aryan languages, but (practically?) not represented in the rest of Dardic. The inherited Kashmiri word for ‘round’ is documented in Kogan’s Srinagar list: ḍulomɨ.

-

7.

SNAKE sarapʰ. Pace IE-CoR, it cannot directly correspond to Vedic sarpá- and its modern Indo-Aryan cognates (all meaning ‘snake’) for phonetic reasons, since rp should be simplified to p(ʰ) (e.g., Kashmiri kapur ‘cotton cloth’ — OInd. karpaṭa- ‘patched garment, rag’, Kashmiri khaphür ‘one half of the cranium’ — OInd. kharpara- ‘skull’, etc., more instances can be extracted from Turner, 1966). Thus, the Kashmiri word is most likely an adaptation of the Sanskrit word.

It is precisely these undetected loans from Indo-Aryan sources that are responsible for the fact that the Dardic language Kashmiri, was placed in the middle of the Indo-Aryan clade in Heggarty et al.’s resulting tree.

Genealogical tree

The genealogical tree of the IE family offered by Heggarty et al. is not convincing for the following reasons: (a) some important nodes have very low probability; (b) the tree is poorly resolved (see below); (c) some important nodes contradict our historical knowledge.

Heggarty et al. themselves have preferred not to publish the outcome tree in the main text of the paper, only reproducing it in the middle of Heggarty et al.’s online Supplement (p. 57, Fig. S6.1).

In the main text only the DensiTree plot is published (Fig. 2), which represents a projection of the numerous competitive trees sampled in the Bayesian analysis. The colored plot with its mess of lines looks very scientifical, but is hard or simply impossible to be interpreted (especially for unskilled readers and particularly because of the low-resolution raster format of the pic).

Heggarty et al.’s IE tree (Supplement, p.57, Fig. S6.1) is the so-called “Maximum clade credibility” (MCC) tree, that is, one of the thousands of sampled trees that has the best total probability (either the product or the sum of probabilities of all nodes is counted).

It can be easily seen that the first bifurcations which occur after the IE break-up have very low probability (<0.5), and some of the nodes are most definitely incorrect, such as the Hittite-Tocharian unity for which there is no serious linguistic evidence and which no Indo-Europeanist could ever agree with. In general, such an unrobust tree makes little sense.

There is, however, reason to believe that a MCC tree is not the optimal format to present a Bayesian inference output (at least for language taxa; we do not discuss biological evolution). A more adequate format seems to be the 50% majority rule consensus tree (MRC), which consists of all bifurcations that appear in 50% or more of the sampled trees. Nodes with a lower statistical support (they appear in less than 50% of the sampled trees) are joined in polytomy, i.e., the low-probability nodes are represented as multifurcations in the resulting MRC tree.

MRC trees have two main advantages. First, MRC is relatively secure in respect to type-1 errors, i.e., the MRC format reduces the chance to obtain false bifurcations in the resulting tree (e.g., Holder et al. 2008, and elsewhere). This is a very important thing, even if some of the historically true bifurcations could also fall into polytomous nodes. Second, MRC is able to depict historically true multifurcations (hard polytomy). Biologists usually believe that any polytomy is in fact a poorly resolved sequence of bifurcations. This should not be the case for the history of languages, however, where fan-like disintegrations may genuinely occur (e.g. in the situation of a simultaneous series of migrations into different directions).

MCC trees, on the contrary, frequently contain bifurcations with low probability, which turn out to be misleading for unskilled readers (this, in particular, is the case with Heggarty et al.’s tree).

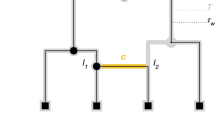

Here (Fig. 1) we present the MRC tree summarized in MrBayes from the sampled trees of Heggarty et al. (‘IECoR_Main_M3_Binary_Covarion_Rates_By_Mg_Bin_combined.trees’ file with 25% burn-in). Technically, this was not a very easy task because of some peculiarities of the BEAST format and undocumented features. Note that the terminal nodes with modern languages are not ideally aligned relative to the zero year in our MRC tree; this is a consequence of conversion between formats. However, such small fluctuations are irrelevant for our current purposes.

50% majority rule consensus tree of the IE languages (summarized from the sampled trees by Heggarty et al. 2023). Bayesian posterior probabilities are shown near the nodes (not shown for stable branches with P ≥ 0.95). Branch lengths reflect absolute chronology (zero is AD 2000). The tree is also available as vector *.pdf and Newick *.tre (see Supplementary Information online).

Our MRC tree (Figs. 1, 2) is very similar, if not identical, to Heggarty et al.’s MCC tree, where low-probability nodes are joined in multifurcations, but the MRC tree allows us to better evaluate which results have actually been obtained by Heggarty et al.

-

1.

The tree starts with a meaningless rake: Hittite, Tocharian, Albanian, Indo-Iranian, Greek-Armenian, Balto-Slavic-Italo-Celto-Germanic. It goes without saying that such a multifurcation makes no historical sense and contradicts our knowledge (see Blažek, 2007; Olander, 2022 for overviews of tree modelings of the IE family).

-

2.

Some trivial clades have high statistical support: Balto-Slavic, Indo-Iranian, Greek-Armenian, West European (i.e., Italo-Celto-Germanic).

-

3.

An interesting result is that Celtic and Germanic form a distinct clade (p = 0.87).

-

4.

A controversial result is that Balto-Slavic is joined with the West European clade (Italo-Celto-Germanic) (low support, p = 0.64), not with Indo-Iranian.

The same 50% majority rule consensus tree (Fig. 1) in a simplified form with proto-languages of the corresponding groups on terminal nodes. The tree is also available as vector *.pdf (see Supplementary Information online).

The peculiarity of Balto-Slavic is that this clade shows specific affinity with both Indo-Iranian and West European, suggesting that at least one of the respective pairings (Balto-Slavic–Indo-Iranian vs. Balto-Slavic–West European) should be explainable as a result of intense linguistic contacts after the separation of these ancestral stages from the main Indo-European stem, but before their subsequent splitting into dialectal clusters.

From the general standpoint of classic comparative-historical linguistics, it is most likely the Balto-Slavic–West European connection that should be judged as more probable to reflect a situation of contact rather than genetic unity. The Balto-Slavic and Germanic-Celtic-Italic linguistic areas were almost certainly in close contact with each other, mostly via the Slavic-Gemanic (or Balto-Slavic–Germanic) “bridge”. These contacts, which probably began some time around the 1st millennium BCE or earlier, went on for millennia and were so intense that this even led some scholars to the idea that Balto-Slavic and Germanic (or, more generally, Germanic-Celtic-Italic) form a distinct clade on the Indo-European tree (see Anthony and Ringe, 2015 for some discussion). These ancient contacts resulted in a substantial number of words, mostly cultural concepts, and local species, shared by Proto-Slavic (and possibly further Baltic) and Proto-Germanic (and possibly further Celtic and Italic) in such a way that these words frequently do not violate regular sound correspondences and thus formally look like traces of Indo-European heritage (Porzig, 1954; Stang, 1972; Nepokupnyj, 1989). However, the geographical distribution of the common Balto-Slavic–Germanic vocabulary, its mostly cultural semantics and its sporadic violation of the Proto-Indo-European phonology and morphology (e.g., words with the phoneme *b) all point to ancient language contacts rather than proto-language ancestry. Among such Slavic-Germanic matches are words such as ‘rye’, ‘turnip’, ‘apple’, ‘alder’, ‘swan’, ‘1000’ etc. There are substantial arguments in favor of many of these words originating from a non-Indo-European substrate (Kroonen, 2012; Matasović, 2013; Iversen and Kroonen, 2017; Matasović, 2020).

Among shared non-lexical innovations that display a common pattern but are more easily explainable through areal convergence than shared ancestry, one can mention the merger of short a and o > a which occurred in parallel in Proto-Balto-Slavic or Proto-Slavic (Kortlandt, 1994, 98; Matasović, 2005, 151) and Proto-Germanic (Kroonen, 2013, xxii, xxxii, xli) and the plural dative and instrumental case endings in *-m- (Hansen and Kroonen, 2022, 164).

On the other hand, the Balto-Slavic–Indo-Iranian pair looks like a typical ancient clade, a fact that might be slightly obscured with later local contacts already after the split of both pairs, e.g. between ancient Slavic and Iranian languages, but becomes more transparent if we specifically operate on the level of the reconstructed Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Indo-Iranian basic lexicon. Within the 110-item Swadesh wordlist, the following exclusive Balto-Slavic–Indo-Iranian innovations can be noted (Kassian, Zhivlov et al. 2021):

-

COLD: Baltic *šal-t-a-, Iranian *сar-ta (further replacements: Slavic *stoːd-en-, Old Indic śītá-).

-

GREEN: Slavic *zel-en-, Baltic *žal-ya-, Old Indic hárita-, Iranian *ʒar-i-.

-

HAIR: Slavic *vals-u, Iranian *warc-a- (further replacements: Baltic *mat-a-, Old Indic kéśa-).

-

TO SWIM: Slavic *ploː-, *pluv-, Old Indic plav-, Iranian *fraw- (further replacements: Baltic *peld-eː).

The list above does not include the following exclusive Balto-Slavic–Indo-Iranian matches, which have a good chance to represent inherited Proto-IE terms for the given meanings, rather than later innovations (however, an innovative explanation for at least some of them is also not out of the question):

-

BLACK: Slavic *čir-n-, Baltic (Old Prussian kirsnan), Old Indic kr̥ṣṇá-.

-

MOUNTAIN: Slavic *gar-aː, Old Indic girí-, Iranian *gar-i-.

-

ROAD: Slavic *pant-i, Old Indic path-, Iranian *pant-aː- ~ *paθ-.

-

STONE: Slavic *kaːm-uː, obl. *kaːm-en-, Baltic *ak-moː, obl. *ak-men-, Old Indic áśman-, Iranian *ac-man-.

On the contrary, there are no reliable Balto-Slavic–West European innovations within our 110-item Swadesh wordlist. Cf. the following case, which is a good illustration for the Balto-Slavic–West European contact scenario:

-

MANY: Germanic *manag-a-, Slavic *munag-a (abnormal root shape, irregular vocalic correspondences). NB: The old Proto-IE root for this concept is retained in Indo-Iranian: Old Indic purú-, Iranian *par-u-, further Old Irish il, Old Greek πολύς, all ‘many’.

Another kind of Balto-Slavic–West European matches can be illustrated with the following etymology:

-

MOON: Slavic (only Russian, Bulgarian, Slovene) *loːn-aː, Latin luːn-a. Even without our knowledge of ancient Slavic languages (the gradual substitution of *meːs-enk-u with *loːn-aː can even be traced in the history of Russian), it is easy to demonstrate that *loːn-aː and luːn-a are innovations in both groups, Slavic and Italic, since (a) other Slavic and Italic languages have the reflexes of *meHn-es- with the meaning ‘moon’; (b) all the involved languages (Russian, Bulgarian, Slovene, and Latin), have the reflexes of *meHn-es- for ‘month’; (c) cross-linguistically, the meaning shift is only normal in the direction of ‘moon’ > ‘month’, not vice versa.

Such cases are likely to be one of the factors responsible for the Balto-Slavic–West European node on the tree, produced by Heggarty et al.

Generally, the authors propose nothing new as compared with the previous experiments of the team (Gray and Atkinson, 2003; Bouckaert et al. 2012). As in the older publications, the date of the IE break-up, 4740–7610 BC, does indeed roughly coincide with the migration of early farmers from Anatolia into Europe ca. 7,000 BC (in this sense, the obtained results continue to support the “farming” hypothesis which associates these farmers with the Indo-Europeans). Note that the more traditional view, recently confirmed by an alternately produced formal phylogeny (Kassian, Zhivlov et al. 2021, 971), is that the initial IE break-up occurred much later, around the first half of the 4th millennium BC.

As for the intermediate Steppe homeland, it is indeed likely that at least some of the IE languages migrated from the Eurasian steppes into Central and Northern Europe in the early 3rd millennium BC. The unresolved question is the exact linguistic configuration and sequence of those out-of-steppe migrations. Heggarty et al.’s answer, [Italic, [Celtic, Germanic]] or [Balto-Slavic, [Italic, [Celtic, Germanic]]], seems no more justified than Heggarty et al.’s general phylogenetic analysis of the IE family.

It should perhaps be added here that the term “hybrid model”, carried over into the very title of Heggarty et al.‘s paper, is rather unfortunate; in classic historical linguistics, a hybrid origin for any particular language family usually refers to the idea of mixed languages, i.e. a multi-ancestry origin, an idea not generally liked by experts in the field and, in any case, having nothing whatsoever to do with the scenario actually advocated for by the authors of the paper under review. Instead, their adoption of the term seems to be subtly advocating for a consensus between supporters of the “Anatolian” and the “Steppe” hypotheses — most likely in vain, since it is hard to see how supporters of the latter could in any case embrace the topology and chronology of Indo-European the way they are presented.

In order to preventively defend their results from criticism by “traditionalist Indo-Europeanists”, Heggarty et al. include several sections of a more theoretical nature into the Supplement, such as an attack on the method of “linguistic paleontology” (Heggarty et al.’s Supplement, pp. 19-21) which, to us, seems highly undeserved and, in places, bordering on the irrational. Essentially, the point argued by the authors is as follows: even when all, or most, of the cognates attested for one proto-lexeme in several daughter languages mean exactly the same thing, this should not count as evidence that the same meaning was also characteristic of the same lexeme in the ancestral language.

Thus, words presumably “reconstructible” for Proto-Indo-European with the meanings ‘wheel’, ‘axle’ (because these are their precise meanings in all/most descendant languages), might have easily meant ‘general concept of rotation/cyclicality’(!) or ‘axis or point of rotation in the night sky, perceived around the pole star’(!) (p. 21); by the same logic, ‘horse’ should naturally be thought of as ‘a kind of wild horse’, even if the word is consistently applied to domesticated horses in all the ancient Indo-European languages and there is no impassable theoretical constraint on Proto-Indo-Europeans being unacquainted with domesticated horses.

While we do not necessarily agree that all semantic shifts have to observe the ‘concrete’ > ‘abstract’ direction rather than vice versa (as is sometimes claimed), we do agree that such patterns are more commonly observed than opposite ones; and if Heggarty et al. wish to convince us that a word specifically referring to an ‘abstract circle’ could arise in a language first and then, later, shift toward the more concrete and material ‘wheel’, serious typological evidence is in order. It gets worse, though: most Indo-Europeanists agree that the reduplicated *kʷekʷlo- ‘wheel’ is a nominal derivate from the verbal root *kʷelh1- ‘to turn; to make a turn’ (Adams and Mallory, 1997, 640; Rix et al. 2001, 386), denoting a dynamic action (in fact, many of its reflexes, including OInd. cárati, Greek πέλομαι, etc., refer to a general idea of ‘movement’ rather than a specifically circular one), so, if anything, this original nominal stem did not so much refer to a static idea of ‘being round’ as it did to ‘an object used for (or to facilitate) movement’ — and what other candidate than ‘wheel’ could that particular object be?

It goes without saying that, “in order to save face”, any extravagant semantic scenario can be offered for the remote prehistoric past, given that we can never access it directly without a time machine and, thus, never truly “prove” anything about it in the mathematical or even judicial sense of the term. But, to the best of our knowledge, nobody has as of yet eliminated such factors as typological evidence, scientific parsimony, and common sense from historical analysis - which is precisely something that the section “Linguistic Paleontology — Did Speakers of Proto-Indo-European Know the Wheel?” of the Supplement to Heggarty et al.’s paper seems to be trying to do. At the very least, if that section decided to focus on, e.g., the lack of the corresponding terms in Anatolian languages (which is quite relevant to anybody who accepts the “Indo-Hittite” hypothesis of an initial bifurcation into Anatolian and “Narrow Indo-European”), it would have made sense. However, the authors are in need of defending their “primordial rake”, which, in their opinion, is well worth demolishing a perfectly valid and reasonable method of semantic reconstruction that has so far worked pretty well in historical linguistics, both for Indo-European and numerous other linguistic families.

Many more specific criticisms of Heggarty et al.‘s datings from the point of view of linguistic paleontology (Wörter und Sachen) may be found in Kroonen et al. 2023, as well as a detailed forthcoming paper by Kroonen et al.; here, we simply would like to remark that in situations when “classic”, perfectly transparent historical linguistic reconstruction comes into direct conflict with the results of a (specific type of) probabilistic modeling, it would seem reasonable to first diligently assess the chosen data and methods for potential flaws rather than generate complicated and typologically questionable historical scenarios to solve the conundrum.

Discussion and conclusions

In the previous sections, we have to tried to identify several factors that might have been responsible for the dubious topological and chronological results of Heggarty et al. 2023 experiment, not likely to be accepted by the majority of “mainstream” Indo-European linguists. Unfortunately, it is hard to give a definite answer without extensive tests, since, in many respects, the machine-processed Bayesian analysis remains a “black box”. We did, however, conclude at least that this time around, errors in input data are not a key shortcoming of the study (as was highly likely for such previous IE classifications as published by Gray and Atkinson, 2003; Bouckaert et al. 2012), although failure to identify a certain number of non-transparent areal borrowings and/or to distinguish between innovations shared through common ancestry and those arising independently of one another across different lineages (linguistic homoplasy) may have contributed to the skewed topography.

One additional hypothesis is that the number of characters (170 Swadesh concepts) is simply too low for the given number of taxa (161 lects). From the combinatorial and statistical point of view, it is a trivial consideration that more taxa require more characters for robust classification (see Rama and Wichmann, 2018 for attempts at estimation of optimal dataset size for reliable classification of language taxa). Previous IE classifications by Gray, Atkinson et al. involved fewer taxa and more characters (see Table 1 for the comparison).

Table 1 suggests that the approach maintained and expanded upon in Heggarty et al. 2023 project can actually be a dead-end in classifying large and diversified language families. In general, the more languages are involved in the procedure, the more characters (Swadesh concepts) are required to make the classification sufficiently robust. Such a task, in turn, requires a huge number of man-hours for wordlist compilation and is inevitably accompanied by various errors, partly due to poor lexicographic sources for some languages, and partly due to the human factor. Likewise, expanding the list of concepts would lead us to less and less stable concepts with vague semantic definitions.

Instead of such an “expansionist” approach, a “reductionist” perspective, such as the one adopted by Kassian, Zhivlov et al. (2021), may be preferable, which places more emphasis on preliminary elimination of the noise factor rather than its increase by manually producing intermediate ancestral state reconstructions (produced by means of a transparent and relatively objective procedure). Unfortunately, use of linguistic reconstructions as characters for modern phylogenetic classifications still seems to be frowned upon by many, if not most, scholars involved in such research — in our opinion, an unwarranted bias that hinders progress in this area.

Overall one could say that Heggarty et al. (2023) at the same time represents an important step forward (in its clearly improved attitude to selection and curation of input data) and, unfortunately, a surprising step back in that the resulting IE tree, in many respects, is even less plausible and less likely to find acceptance in mainstream historical linguistics than the trees previously published by Gray & Atkinson (2003) and by Bouckaert et al. (2012). Consequently, the paper enhances the already serious risk of discrediting the very idea of the usefulness of formal mathematical methods for the genealogical classification of languages; it is highly likely, for instance, that a “classically trained” historical linguist, knowledgeable in both the diachronic aspects of Indo-European languages and such adjacent disciplines as general history and archaeology, but not particularly well versed in computational methods of classification, will walk away from the paper in question with the overall impression that even the best possible linguistic data may yield radically different results depending on all sorts of “tampering” with the complex parameters of the selected methods — and that the authors have intentionally chosen that particular set of parameters which better suits their already existing pre-conceptions of the history and chronology of the spread of Indo-European languages. While we are not necessarily implying that this criticism is true, it at least seems obvious that in a situation of conflict between “classic” and “computational” models of historical linguistics, assuming that the results of the latter automatically override those of the former would be a pseudo-scientific approach; instead, such conflicts should be analyzed and resolved with much more diligence and much deeper analysis than the one presented in Heggarty et al. 2023 study.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this article and its supplementary files.

Notes

The dataset is freely available at https://iecor.clld.org/

https://iecor.clld.org/parameters > the option “More”.

https://iecor.clld.org/languages/kashmiri. We are sincerely grateful to Anton Kogan (Moscow) for his extensive comments on the Kashmiri data discussed in this section.

References

Adams DQ, Mallory JP (1997) Wheel. In: Mallory, JP, Adams, DQ (eds.) Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, London, pp. 640–641

Anthony DW (2013) Two IE phylogenies, three PIE migrations, and four kinds of steppe. J. Lang. Relatsh. 9:1–21

Anthony DW, Ringe D (2015) The Indo-European homeland from linguistic and archaeological perspectives. Annu. Rev. Linguist. 1(1):199–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-124812

Blažek V (2007) From August Schleicher to Sergei Starostin. On the development of the tree-diagram models of the Indo-European languages. J. Indo-Eur. Stud. 35(1):82–109

Bouckaert R, Lemey P, Dunn M et al. (2012) Mapping the origins and expansion of the Indo-European language family. Science 337:957–960. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1219669

Chang W, Cathcart C, Hall D et al. (2015) Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis. Language 91(1):194–244. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2015.0005

Costakis A (Thanasis) P (1951) Σύντομη γραμματική τής τσακωνικής διαλέκτου [Brief grammar of the Tsakonian dialect]. Institut Français d’Athènes, Athens

Egorov IM, Dybo AV, Kassian AS (2022) Phylogeny of the Turkic languages inferred from basic vocabulary: limitations of the lexicostatistical methods in an intensive contact situation. J. Lang. Evol. 7(1):16–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/jole/lzac006

Gray RD, Atkinson QD (2003) Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426:435–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02029

Hansen BSS, Kroonen G (2022) Germanic. In: Olander, T (ed.) The Indo-European language family: A phylogenetic perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 152–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108758666

Heggarty P, Anderson C, Scarborough M et al. (2023) Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages. Science 381(6656):eabg0818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg0818

Holder MT, Sukumaran J, Lewis PO (2008) A justification for reporting the majority-rule consensus tree in Bayesian phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 57(5):814–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150802422308

Iversen R, Kroonen G (2017) Talking Neolithic: linguistic and archaeological perspectives on how Indo-European was implemented in Southern Scandinavia. Am. J. Archaeol. 121(4):511–525. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.121.4.0511

Kassian AS (2015) Towards a formal genealogical classification of the Lezgian languages (North Caucasus): testing various phylogenetic methods on lexical data. PLOS ONE 10(2):e0116950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116950

Kassian AS (2017) Linguistic homoplasy and phylogeny reconstruction. The cases of Lezgian and Tsezic languages (North Caucasus). Folia Linguist. 51(s38):217–262. https://doi.org/10.1515/flih-2017-0008

Kassian AS (2023) Lexicostatistics. Edited by ML Greenberg and LA Grenoble. Greenberg, ML, Grenoble, LA (eds.) Encyclopedia of Slavic Languages and Linguistics Online. Brill, Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/2589-6229_ESLO_COM_047338

Kassian AS, Starostin G, Dybo A et al. (2010) The Swadesh wordlist. An attempt at semantic specification. J. Lang. Relatsh. 4:46–89

Kassian AS, Starostin G, Egorov IM et al. (2021) Permutation test applied to lexical reconstructions partially supports the Altaic linguistic macrofamily. Evol. Hum. Sci. 3(e32). https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2021.28

Kassian AS, Starostin GS, Zhivlov MA (2015) Proto-Indo-European-Uralic comparison from the probabilistic point of view. J. Indo-Eur. Stud. 43(3–4):301–347

Kassian AS, Testelets YG (2017) Pitfalls of shared innovations: Genealogical classification of the Tsezic languages and the controversial position of Hinukh (North Caucasus). Lingua 196:98–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2017.06.011

Kassian AS, Zhivlov MA, Starostin GS et al. (2021) Rapid radiation of the Inner Indo-European languages: an advanced approach to Indo-European lexicostatistics. Linguistics 59(4):949–979. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2020-0060

Kogan AI (2005) Dardskie jazyki. Genetičeskaja xarakteristika [Dardic languages. Genealogical analysis]. Vostochnaya Literatura, Moscow

Kogan AI (2011) K xarakteristike indoarijskix èlementov v jazyke kašmiri [On the nature of Indo-Aryan elements in the Kashmiri language]. J Lang Relatsh 5:23–47

Kogan AI (2016) Problemy sravnitelʹno-istoričeskogo izučenija jazyka kašmiri [Issues in comparative historical study of the Kashmiri language]. Fond razvitija fundamentalʹnyx lingvističeskix issledovanij, Moscow

Kortlandt F (1994) From Proto-Indo-European to Slavic. J. Indo-Eur. Stud. 22:91–112

Kroonen G (2012) Non-Indo-European root nouns in Germanic: evidence in support of the Agricultural Substrate Hypothesis. In: Grünthal, R, Kallio, P (eds.) A linguistic map of prehistoric Northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia, 266 Société Finno-Ougrienne, Helsinki, pp. 239–260

Kroonen G (2013) Etymological dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary series, 11. Brill, Leiden

Kroonen G, Olander T, Nørtoft M et al. (2023) Archaeolinguistic anachronisms in Heggarty et al. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.10113208

Lehmann WP (1986) A Gothic etymological dictionary. Brill, Leiden

Mallory JP (2013) Twenty-first century clouds over Indo-European homelands. J. Lang. Relatsh. 9:145–154

Matasović R (2005) Toward a relative chronology of the earliest Baltic and Slavic sound changes. Baltistica 40(2):147–157

Matasović R (2013) Substratum words in Balto-Slavic. Filologija 60:75–102

Matasović R (2020) Language of the bird names and the pre-Indo-European substratum. In: Garnier, R (ed.) Loanwords and substrata: proceedings of the colloquium held in Limoges (5th-7th June, 2018). Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, 164 Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck, pp. 331–344

Nepokupnyj AP ed. (1989) Obščaja leksika germanskix i balto-slavjanskix jazykov [The shared vocabulary of Germanic and Balto-Slavic]. Naukova dumka, Kiev

Olander T (2022) Introduction. In: Olander, T (ed.) The Indo-European language family: A phylogenetic perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108758666

Pereltsvaig A, Lewis MW (2015) The Indo-European controversy: facts and fallacies in historical linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Pernot H (1934) Introduction a l’étude du dialecte tsakonien. Les Belles Lettres, Paris

Porzig W (1954) Die Gliederung des indogermanischen Sprachgebiets. C. Winter, Heidelberg

Rama T, Wichmann S (2018) Towards identifying the optimal data size for lexically-based Bayesian inference of linguistic phylogenies. In: Bender, EM, Derczynski, L, Isabelle, P (eds.) Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Association for Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, pp. 1578–1590

Rix H, Kümmel MJ, Zehnder T et al. (2001) Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben: die Wurzeln und ihre Primärstammbildungen. 2nd ed. Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden

Stang CS (1972) Lexikalische Sonderübereinstimmungen zwischen dem Slavischen, Baltischen und Germanischen. Universitetsforlagets, Oslo

Starostin GS (2010) Preliminary lexicostatistics as a basis for language classification: A new approach. J. Lang. Relatsh. 3:79–116

Starostin GS (2013) Lexicostatistics as a basis for language classification: increasing the pros, reducing the cons. In: Fangerau, H, Geisler, H, Halling, T, Martin, WF (eds.) Classification and evolution in biology, linguistics and the history of science: concepts - methods - visualization. KulturAnamnesen, 5 Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, pp. 125–146

Swadesh M (1955) Towards greater accuracy in lexicostatistic dating. Int. J. Am. Linguist. 21:121–137

Turner RL (1966) A comparative dictionary of Indo-Aryan languages. Oxford University Press, London

Acknowledgements

AK: The article was prepared on the basis of the RANEPA state assignment research program. GS: The work was carried out with support from the research project “From Antiquity to Modernity” (National Research University Higher School of Economics, FI-2025-28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassian, A.S., Starostin, G. Do ‘language trees with sampled ancestors’ really support a ‘hybrid model’ for the origin of Indo-European? Thoughts on the most recent attempt at yet another IE phylogeny. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 682 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04986-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04986-7