Abstract

Promotion is a key reward in academic science normatively associated with performance. Women are underrepresented in science across most countries, particularly in senior roles. Our study investigates the role of merit and several other factors in the promotion to full professor and senior researcher in public scientific institutes, and whether differences between women and men exist. We analyse 90 different promotion events at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) from 2017 to 2021 across scientific fields, including 2338 applicants and 397 members of evaluation committees. We have created two different data sets; one of applicants, combining individual and career information with scientific performance data (publications, citations, impact, projects, contracts, patents, and PhD supervision) and another one of evaluation panels members. We have integrated the two data sets for each evaluation panel and determined the competitive conditions of every promotion event. Using logistic regression models and estimating predicted probabilities, we address the role of merit in promotion, the effect of competition and panel composition and weather gender plays a significant role, including potential gender differences. Our findings show that performance does matter and gender is not relevant to explain individual promotion outcomes. Evidence shows that female and male applicants possess comparable merits. Scientific achievements (especially leadership in project funding and citation impact) are important predictors of promotion probabilities across genders. Most importantly, we do not find evidence that men and women with similar performance have different promotion probabilities. Our findings reveal additional influential elements beyond scientific performance. Specifically, institutional proximity or connections between applicants and evaluators is an important factor, in addition to the effects of competitive pressure within each promotion event, however those effects are not gendered. Some of our results raise concerns about the fairness of the promotion process. We discuss the findings and some organisational policy implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: relevance, research questions and contribution

Merit and scientific performance are factors normatively accepted as key determinants of rewards and promotion (Merton, 1942), typically assessed through peer review evaluation in academic research (Bornmann, 2011). However, concerns are often raised about the impartiality, fairness and reliability of this evaluation method and whether it is susceptible to various types of bias (Lee et al., 2013).

Women are underrepresented in science across most countries, particularly in senior positions (Ceci et al., 2018; Kahn and Ginther, 2018; Larivière and Sugimoto, 2017; Sugimoto and Larivière, 2023). However, recent reports indicate a trend of narrowing gender gaps (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission), 2021; OECD, 2024). If this underrepresentation results from equally qualified women being promoted at lower rates than men, this warrants further investigation. Hence it is relevant to empirically analyse the factors influencing promotion to scientific senior roles in competitive environments.

Descriptive evidence about gender gaps has often been interpreted as indicative of bias, particularly when relying on indicators such as success rates in competitive processes. However, drawing conclusions of bias solely from gender gaps data is not warranted. The insufficiency of this approach has been highlighted if other factors, including merit assessment, are overlooked. (Ceci et al., 2023).

Historical evidence indicated that women achieved high academic ranks later than men (Cole and Zuckerman, 1984), that women were less likely to be promoted (Cole, 1979) or experienced slower rates of promotion compared to similarly qualified men (Long et al., 1993; Sonnert and Holton, 1995); these findings linked gender gaps to a lower productivity of women (Xie and Shauman, 2003) and differences in age and life cycle productivity (Stephan and Levin, 1992).

The factors influencing the promotion of women and men to scientific senior positions are complex and context-dependent. For instance, these factors include: evaluation criteria and processes (Cruz-Castro and Sanz-Menéndez, 2021; Fox, 2015; Fox and Xiao, 2013; Sanz-Menéndez and Cruz-Castro, 2019), differences in productivity or quality (Kwiek and Roszka, 2022; Sugimoto and Larivière, 2023; Thelwall and Mas-Bleda, 2020; Wu, 2023, 2024), partiality among reviewers (Derrick, 2019; Lee et al., 2013), connections with evaluators (Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2015) or field segmentation (Leahey et al., 2008). A thorough diagnosis is essential for identifying key factors and develop plausible hypotheses which help improve understanding and refine policy.

The underrepresentation of women in science remains a significant issue worldwide, especially when linked to inequality in evaluations. Over the past 20 years governments, funding agencies, and research organisations have implemented gender equality policies. For instance, Spain has mandated gender parity in evaluation committees since 2007 (González Ramos et al., 2020), and the EU has included Gender Equality Plans in the recommendations from the Human Resources Strategy for Researchers (HRS4R) promoted by the European Commission (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission), 2024).

By analysing the data offered by the largest research institution in Spain, specifically its 90 evaluation processes for promotion to the two senior scientific categories (Scientific Researcher (INVE) and Research Professor (PROF)) in three different calls issued in 2017, 2019, and 2021, involving 2338 candidates’ applications, 539 promoted researchers, and 397 members of evaluation panels, we investigate the following:

-

Do merit factors positively affect individual promotion probabilities? Are there any gender differences in this respect?

-

Does gender play a significant role in promotion probabilities?

-

Are there other factors associated with the composition of the panels and the competition that affect unequal promotion probabilities for candidates?

We contribute to the literature in various ways. First, with a comprehensive study of all promotion processes covering all fields rather than just a sample of disciplines, as most previous studies.

Second, complementing studies focusing on early career and tenure hiring in Spain (Cruz-Castro and Sanz-Menéndez, 2010; Sanz-Menéndez et al., 2013), our research investigates further promotions at the two distinct senior levels, providing additional insights into the factors influencing career progression across different stages of research careers.

Third, we have expanded the range of indicators used to assess applicants’ performance, going beyond traditional bibliometric measures dominant in previous research.

Fourth, our analysis focuses on CSIC, the largest Spanish research institution, that shares institutional characteristics with others across Europe, such as CNRS in France, MPG in Germany, or CNR in Italy, as well as CONICET in Argentina and others worldwide. These institutions prioritise scientific and technological research as their primary mission. This distinction from universities is relevant, as it minimises measurement issues associated with teaching or service responsibilities, which often impact gender-related outcomes.

Fifth, while recent observational studies have increasingly incorporated the influence of evaluation panels, particularly within research funding agencies, the inclusion of relevant attributes of evaluators or relationships with applicants remains uncommon in observational studies on academic promotion.

Finally, we contribute to the field by controlling for the competitive conditions in each promotion event, enabling us to empirically assess whether promotion probabilities differ between women and men or vary in response to competition.

This article is organised as follows: In section 2, we review findings and factors related to promotion and gender in previous research. Section 3 describes the promotion at CSIC as our context for analysis, details the data construction and outlines the modelling strategy. Section 4 presents the empirical results of our analysis. Finally, we discuss our findings in relation to existing evidence and draw some conclusions.

Findings and factors shaping promotion by gender

This section highlights key findings from previous research on academic promotion and gender. This research spans different countries, time periods, academic systems and fields (see a selection of contributions in the Annex).

Studies with a focus on individual attributes

Some studies have analysed academic promotion with a focus on gender effects, without considering performance. For instance, analysis examining all full-time faculty members at Canadian universities, from 1984 to 1999, found that the median time for women to be promoted from associate to full professor was 8.3 years, one year longer than for men. This gender difference persisted across disciplines and institutions, suggesting that variations in these factors had minimal impact on promotion dynamics (Stewart et al., 2009).

At US universities, earlier research generally showed men being more likely than women to receive promotions at various stages of their careers (Long et al., 1993). Longitudinal analyses that track transitions over time, usually distinguish between promotion outcomes and attrition dynamics. Some found no significant gender differences in faculty retention from hiring to departure but did find that men were more likely than women to be granted tenure (Box-Steffensmeier et al., 2015). Others found diverse patterns across fields, with female engineering assistant professors more likely to leave without tenure compared to men, a pattern not seen in other STEM fields; median promotion times from associate to full professor were similar for men and women in engineering and physical/mathematical sciences, but were one to two years longer for women in biological sciences (Gumpertz et al., 2017).

In Australia it was found that female lecturers were less likely than men to be promoted or leave, while female associate professors were more likely to be promoted. Additionally, analyses indicated that gender differences decreased over time and leave-taking did not explain the observed gender differences in promotion (Kahn, 2012).

In Europe, a study of gender differences in promotion probabilities among academic staff at a large Dutch university, showed that women had lower promotion probabilities compared to men. These differences were mainly associated to variations in years of service and external mobility (Groeneveld et al., 2012). In contrast, men and women had equal probabilities of achieving postdoctoral fellowships and progressing to professorships in Sweden, suggesting that the system did not discriminate against women (Danell and Hjerm, 2013).

In general, research on gender and promotion across different countries and institutions has yielded mixed results, highlighting the importance of fields and understanding the relationship between attrition and promotion. Examining promotion across ranks is crucial for understanding gender differences. Typically, studies that do not account for performance factors often find that women face disadvantages in promotions. Besides gender, another individual attribute generally considered in this literature is seniority, measured by years of service, or by rank.

Studies including performance

In a system that operates on the principle of universalism, meritocracy has been suggested as a potential explanation for gender differences in promotion (Tien, 2007), under the hypothesis that women generally exhibit less performance than men. Some have questioned this explanation, suggesting that gender gaps in outcomes could also arise from structural factors such as field segmentation, if women disproportionately work in fields with worse promotion opportunities (Cech and Blair-Loy, 2010). Also, gender inequality at the time of the promotion would be suggested if men and women with equivalent performance in similar organisations are promoted at different rates. These factors can contribute to disparities in outcomes beyond considerations of merit alone (Reskin and Bielby, 2005).

Merit comparison for career advancement traditionally rely on research outcomes, measured through publications and bibliometric indicators (Long, 1978; Long et al., 1993; Reskin, 1976). Extensive literature examines gender disparities in scientific productivity yielding contradictory findings (Ceci et al., 2023; Mairesse and Pezzoni, 2015; Ni et al., 2021; Sugimoto and Larivière, 2023; Thelwall and Mas-Bleda, 2020; van Arensbergen et al., 2012; van den Besselaar and Sandström, 2016, 2017, 2019). Studies that use papers as the unit of analysis show no clear evidence of gender differences in productivity; however, those considering researchers as units of analysis, suggest women exhibit lower productivity potentially due to shorter academic and research careers and higher exit rates, or to lower recognition by peers (Card et al., 2020, 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Wu, 2023, 2024).

A notable body of literature that integrates merit factors into the analysis of academic promotion focuses on the US context. Kahn and Ginther (2018) found only small gender differences in promotion probabilities but showed negative effects of maternity for women in their early career. Among the works finding that men were favoured in tenure promotions, even after accounting for several measures of productivity (number of publications, citations, impact factor, and grants), Weisshaar (2017) suggested that gender bias and departmental characteristics contributed to this disparity, with women more likely to receive tenure in lower-prestige departments. Others report that women were less likely to hold prestigious endowed chairs compared to men, even when controlling for performance -measured by number of publications in top journals and citations- (Treviño et al., 2018).

Findings are different in other national systems. A study of German sociologists found that academic productivity, measured by publications, was a strong predictor of tenured professorship. However, factors like network size and gender also played significant roles. Interestingly, women were more likely than men to obtain tenure with fewer publications. Lutter and Schröder (2016) aligned with previous findings that also observed positive effects of gender in academic appointments at German universities across various disciplines (Jungbauer-Gans and Gross, 2013). Others found that while female academics applied less for tenured positions, they had a fair chance of being shortlisted (Auspurg et al., 2017). These studies indicated that women’s publishing efforts were valued equally when seeking tenure and lower hiring rates of women were related to attrition, rather than being less likely hired despite comparable productivity to men (Habicht et al., 2024; Lutter et al., 2022; Schröder et al., 2021).

Early studies on Public Research Organisations (PRO) like the French CNRS, INRA or INSERM suggested a glass ceiling for women in senior PRO roles (Lissoni et al. 2011; Sabatier, 2010; Sabatier et al., 2006). However, more recent analyses found a limited glass ceiling for women on access to professorships in physics, management, and history, noting that competition intensity, rather than candidate performance primarily influenced access as positions became scarce (Sabatier et al. 2015). Research in French universities and PROs shows similar trends in physics (Mairesse et al., 2020) and economics (Bosquet et al., 2019) with women less likely to pursue promotions, but gender having no impact on promotion rates for those who applied; when controlling for productivity, there were no significant differences in promotion probabilities, although women generally had slightly lower productivity, measured by the number of publications, h index and the quality of journals.

In promotion systems that require getting external ex ante promotion credentials, like Italy, among those who obtained accreditation and with equal productivity (same measures as above), men had a 24% higher probability of being promoted to full-professorship (Marini and Meschitti, 2018); the authors attributed this to gender bias at the internal department level, where there is less transparency.

Some longitudinal research highlights the relevance of career stage showing that productivity differences between men and women are minimal early in their careers but become more pronounced later, impacting career advancement, as 61% of male researchers attained associate or full professorships over a decade, compared to only 32% of women (van den Besselaar and Sandström, 2016). Similarly, recent evidence highlights persistent gender gaps in appointments to full professorships, particularly among cohorts from 2000–2005 not attributable to differences in performance, measured by number of publications, top citations and journal impact factor (Mom et al., 2022). Slower promotion to full professorship has been recently reported for women in Norwegian academia in the first decade after the doctoral degree (Aksnes et al., 2025).

The relevance of career stage or seniority has also been noted in previous research that has examined the link between promotion and scientific outputs at the Spanish CSIC, finding similar productivity of males and females in two scientific domains from 1996 to 2000 (Mauleón et al., 2008). However, women with intermediate levels of seniority (years of work experience) exhibited lower research impact (measured by citations) than their male counterparts, and this discrepancy may help explain the slower promotion observed for female scientists.

A recent analysis of the promotion transitions for all eligible candidates of the Argentinean CONICET, for two scientific domains in 2013–2014, found that seniority, publications, and other merits were the primary predictors of promotion, and gender was not a significant factor (D’Onofrio and Rogers, 2022).

In sum, recent analyses considering individual attributes (mainly gender, age and seniority) and merit factors (mainly measured by bibliometric indicators) across various countries and institutional contexts, provide some but limited support for the claim that women fare worse than equally qualified men in academic promotion. However, the gender gap in productivity remains an unresolved issue in research. Additionally, more research is needed to determine whether women who fare equally well as men in promotion processes exhibit (positive) self-selection, reflecting higher performance among female applicants. A recent review of gender bias in six domains, including tenure and hiring (Ceci et al., 2023) found that while women apply less frequently than men, they perform as well or better when they do apply.

Studies introducing the attributes of evaluators

Peer review has traditionally served as the method for assessment in academic science (Bornmann, 2011; Derrick, 2019; Hug, 2022) hence the importance of incorporating evaluators into the analysis.

Previous research has explored various aspects of panel characteristics and evaluation processes in research funding; this includes examining panel composition and parity and their relations with applicants (Bol et al., 2022; Jayasinghe et al., 2003; Marsh et al., 2009, 2011; Mom and van den Besselaar, 2022; Olbrecht and Bornmann, 2010); when gender bias is the focal point, studies incorporating the characteristics of both applicants and evaluators have generally yielded negative results. Instead, factors such as the “luck of the reviewer draw” (Cole et al., 1981), the “most similar to me” (Banal-Estañol et al., 2023), and having a colleague or co-author in the evaluation panel are highlighted.

Some of these studies found that, controlling for productivity, measured by publications, citations and the h-index, female candidates were less likely to be promoted to associate and full professor when the committee was composed exclusively of males, whereas the gender gap disappeared when evaluated by a mixed-gender committee (De Paola and Scoppa, 2015).

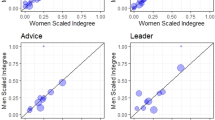

However, other works (Bagues et al., 2017, 2019; Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2015) have not consistently found such an effect and suggest that the role of evaluators’ gender is confused or mixed with the role of connections, operationalised through supervision, co-authorship and common institutional affiliation. The impact of connections and collaboration between candidates and evaluators on the probabilities of promotion is also emphasised in other analyses (Abramo et al., 2015, 2016) who find a positive effect on the promotion probability of candidates with joint research or common institutional affiliation with the president of the committee. Another interesting finding is that common institutional affiliation (years in the same university) has a higher influence for men than for women.

In the literature including attributes of evaluators as well as applicants, the variables are generally gender and affiliation for the former, and gender, affiliation and seniority for the latter.

Context, data and methods

The promotion process in a nutshell

CSIC has three permanent categories of researchers: “Scientist” (usually the entry tenured category), “Scientific Researcher”(INVE) and “Research Professor”(PROF). Annually, calls for promotionFootnote 1 are issued, and members of lower categories decide whether to apply. These calls define the maximum number of positions in each scientific specialty, and publish the composition of evaluation panels. The process is competitive, and the number of promoted candidates cannot exceed the maximum positions approved within each scientific specialty, that is the level at which the competitions are developed.

The evaluation process consists of two phases, and the first phase is eliminatory. The merit criteria and their weighting are the same for the promotion to the two uppers ranks (see Supplementary Information. SI-1). The process ends in a proposal for promotion among those who have passed both phases. The evaluation panel orders them accordingly, promoting only the top candidates up to the number of available positions.

Data, variables and models

Scope

The data for this study includes all promotion processes to the two highest research categories at the CSIC, with calls issued at 2017, 2019 and 2021. To analyse promotions within specific “arenas” of competition, each scientific specialty was treated as the unit of observation. In total, 90 scientific specialties were observed: 51 for promotion to “Senior Researcher” (INVE) and 39 for promotion to “Research Professor” (PROF). These scientific specialties were evaluated by 64 different panels.

The total number of applicants has been 961 for PROF and 1377 for INVE, with successful applicants totalling 164 (18.1%) for PROF, and 375 (27.2%) for INVE. The overall average success rate during the study period was 22.9%. We found minor non-significant differences in success rates between women and men. For INVE promotions, success rates tended to favour women (27.6% vs 27.0%), whereas for PROF promotions, men had a slight advantage (17.7% vs. 15.6%). These success rates varied by year, conditional on the number of available positions, and among different scientific specialties, reflecting the initial allocations of positions to them (see descriptive statistics and correlation tables in Supplementary Information. SI-2).

Data production strategy

The data production strategy combines public data and the administrative records from CSIC databases of applicants and evaluation panel members for the creation of a research database. It also includes publication indicators and past performance information related to research funding and other scientific outputs.

For the analysis, we compiled a database containing demographic, career, and performance variables for the 2338 candidates. Additionally, a database was constructed for the 397 members of the evaluation panels. These two datasets were linked based on the shared participation of evaluators and applicants in each promotion event (see Supplementary Information. SI-3).

The unit of analysis is the application and we characterise applicants at that time. Firstly, we have gathered individual attributes of applicants, from public and administrative sources, including gender, age, and seniority (number of years in the category) at the time of application. Secondly, we have included merit-related information for each applicant from public (SCOPUS) and organisational databases, relevant to the evaluation criteria. These include publications, citations, normalised impact factor, patents, funded projects as principal investigator (PI), contracts, and supervision of granted PhDs. Thirdly, to account for potential effects from evaluation panels we included factors such as their gender composition. We also built attributes for each applicant in interaction with the panel members and specialty. Among these are whether an applicant is affiliated with the same CSIC Institute as at least one panel member or the panel chair, and whether there are other applicants to the same specialty from the same CSIC institute. We also included a general indicator of the level of competition in each specialty. Lastly, we introduced the science domains to control for the potential differences among fields in promotion practices.

Together, these variables allow us to investigate the influence of factors that the literature identifies as relevant for promotion and group them into categories. The description, operationalisation and measurement of the variables is summarised and presented in Table 1 (see also more details on Supplementary Information. SI-3).

Modelling the probabilities of promotion

We estimate the probabilities of promotion using a logistic regression. Logistic regression is a statistical method (Hosmer et al., 2013) used to model the relationship between one or more independent variables and a binary outcome variable. In our study, the outcome variable is whether a candidate is promoted or not, and the independent variables include individual factors, performance indicators, connections with panel members and competitive conditions. In simpler terms, logistic regression models help establish how these independent variables relate to the likelihood of promotion, while controlling for others. In such models, the coefficient of interest usually is the odds ratio.

In our study, logistic regression is used in two approaches: one investigates factors influencing promotion overall, while the other examines gender differences in promotion risk. The methodology estimates effect sizes and assesses the relative importance of competing independent variables aiming to understand the net impact in promotion likelihood. In Fig. 1 we represent the different sets of factors competing for the explanation.

Logistic regression models enable to estimate predicted probabilities which provide insights beyond statistical significance and direction of effects for individual variables, especially when comparing two groups such as men and women (Allison, 1999). Predicted probabilities facilitate group comparisons of marginal effects of each variable on the probability of promotion. They offer a more comprehensive understanding of how individual variables influence outcomes when other variables are held constant or at average values. Differences in outcome probability and marginal effects of regressors on probability underscore the various ways in which groups (in this case, men and women) may vary in their likelihood of promotion. It has been shown that differences in the degree of residual variation across groups can produce differences in the coefficients that are not indicative of true differences (Allison, 1999; Williams, 2012); then we follow recent recommended practices on this issue that suggest that the approach is preferable to running separate models for men and women (Gelman et al., 2020; Imbens, 2021; Long and Mustillo, 2021; Mize et al., 2019; Mood, 2010; Williams, 2012)Footnote 2.

Analysis and findings

We analyse promotion outcomes conditional on applicationFootnote 3 Tables 2 and 3 present the logistic regression results for the promotion to Research Professor (PROF) and Scientific Researcher (INVE). We introduced the relevant factors into the models and we present our results in the same order; the tables include coefficients, error terms and significance levels.

Model 1 includes only the performance variables; model 2 adds the gender of applicants; model 3 includes other individual attributes; model 4 adds competition levels in specialties; model 5 includes panel attributes and relations with applicants, and the final model 6 also controls for differences in science domains.

These models identify the most relevant factors influencing promotion probabilities, including their size and direction. We also assess significance, confidence intervals, p values, and error terms to better gauge the uncertainty of estimates (see Supplementary Information. SI-6).

For comparing differences across genders for variables that are significant for the two promotion ranks, instead of using odds ratios, we use probabilities (Long and Mustillo, 2021; Mood, 2010; Williams, 2012).

The role of merit

A descriptive comparison of promoted and non-promoted applicants across various performance indicators show that the former outperformed the latter (see Supplementary Information. SI-7). The comparison by gender did not reveal systematic substantial differences. Sometimes men performed better on average, while in other cases, women outperformed men. These general observations, confirming considerable heterogeneity, held true across different performance indicators, science domains, and categories.

Results from the regression revealed that several merit factors significantly increase promotion probabilities and explain variance. Most merit factors show positive effects although some are not statistically significant. The most influential factor in size effect, for both promotion categories (PROF and INVE) is being the principal investigator (PI) of research projects.

Close behind in importance is the number of citations received by candidates, which also positively impacts promotion probabilities. For INVE promotions, the number of patents has a positive and significant effect, indicating that technological products are becoming more important for new generations.

When analysing the predicted probabilities for promotion of women and men, based on the levels of certain performance indicators, we found no consistent pattern favouring one gender over the other. For example, in promotions to PROF, women require a slightly higher level of citations (all else being equal) to achieve the same predicted probabilities as men. This difference becomes more pronounced towards the extreme end of the distribution, as shown in Fig. 2. Conversely, for promotion to INVE, men need slightly more citations (all else equal) to achieve the same predicted probabilities as women. However, this difference increases at a slower rate compared to the PROF promotion, as we progress towards the distribution extremes.

Similar trends are noted regarding the number of projects as PI. In PROF promotions, women need slightly more projects (all else equal) to have the same predicted probabilities as men. This difference increases as we move towards the distribution extremes as shown in Fig. 3. Conversely, for promotion to INVE positions, men need slightly more projects (all else equal) to achieve the same predicted probabilities. Again, this difference increases at a slower rate compared to the promotion to PROF.

This mixed evidence, varying by category, indicate a general alignment of the promotion outcomes with normative values of merit and suggests no systematic gender bias against females in the evaluation.

Is gender a significant factor for promotion?

In the regression models, gender is not significant for promotion to any of the two categories. Figure 4 represents the predicted probabilities of promotion to PROF (17.7 for males vs 16.0 for females) and INVE (26.8 for males vs 28.8 for females).

Upon introducing other personal attributes into the models, we observed that the gender variable remains non-significant, indicating only marginal differences.

As shown, seniority, measured by years in the current category, emerges as a significant positive predictor of promotion. Generally, individuals with more seniority have higher probabilities of promotion compared to those with less, particularly in promotion to PROF. However, the relationship between gender and seniority varies within each promotion category, as Fig. 5 shows.

In the promotion to PROF, females with less seniority (under 8 years in the category) exhibit higher promotion probabilities than males with the same seniority. However, as seniority increases, this pattern reverses, with males showing higher, though decreasing probabilities of promotion, than females of the same seniority.

In the promotion to INVE, a similar pattern is observed. Females with less seniority (under 15 years in the category) have substantially higher promotion probabilities compared to males. As seniority increases, this trend shifts, and males exhibit higher promotion probabilities than females. There are two different speeds in promotions and optimal seniority times for promotion, varying by gender.

The interaction between gender and seniority shows that females in both categories have higher promotion probabilities than males when they have less seniority.

Interpretations of these interactions are complex. Several factors could be at play: women who apply might be self-selected at lower levels of seniority and better qualified than men; younger generations may have higher performance overall, indicating a leverage trend; or new cohorts may benefit from more equality policies and higher female success rates than in the past.

As a summary, when considering the models globally, gender does not emerge as a statistically significant or influential factor. However, the analysis of seniority (years in the category) shows an advantage for women among the less senior applicants, significantly increasing their promotion probabilities.

The effects of panel composition and competition

Findings from the regressions indicate that the percentage of women on the panel affect promotion outcomes. In cases where it is statistically significant, such as for INVE promotions, an increase in the share of women on the panel is associated with a slight decrease in the promotion probabilities of female candidates.

We have also identified other factors associated with the composition of evaluation panels that affect unequal probabilities for candidates, but no significant gender patterns have emerged.

In Fig. 6 we observe a consistent and substantial advantage for candidates whose applications are evaluated by a panel that includes a member from their own institute (connections). This measure of institutional proximity significantly increases promotion probabilities, compared to candidates with similar characteristics but without such connection. For PROF promotions, the probabilities for applicants with institutional connections are around 24%, compared to about 14% for those without. In contrast, for INVE promotions, the probabilities for applicants with connections are around 33% compared to about 25% for those without such connection.

Connections (same institute evaluator) emerge as a strong factor, potentially making a crucial difference in the selection of candidates, especially among those with small differences in performance. The predicted probabilities confirm that there are not significant gender-related effects associated with having an evaluator from the own institute in the evaluation panel.

Furthermore, when there are multiple candidates from the same institute in the specific specialty, it has a negative effect on promotion probabilities. Interestingly, this effect is statistically significant only in the case of PROF promotions (see Table 2). Moreover, having another competitor from the same institute diminishes the positive effect of having an institute’s colleague in the evaluation panel. This suggests that panel members’ preferences for colleagues may need to be balanced and negotiated when multiple candidates from the same institute are under consideration.

Finally, an important finding emerged regarding competitive conditions: as expected, increases in competitive pressure within specialties reduce the probabilities of applicants, but the effect of competitive pressure is not gender-specific. There are no significant differences between men and women in how competitive pressure affects promotion probabilities, especially at higher levels of competition, as shown in Fig. 7.

Discussion and conclusions

This article has studied how various factors, such as performance indicators, individual attributes, panel composition, and institutional connections, influence promotion outcomes in research institutes. Our analysis suggests that while certain disparities exist, they may not be as systematically gendered as previously thought. The findings emphasise the need for continued scrutiny of evaluation processes to ensure fairness and transparency in academic and research institutions.

In the models, gender is not a significant variable when controlling for other relevant factors. While there are small, non-significant, differences in favour of women in promotion to Scientific Researcher (INVE), and of men in promotion to Research Professor (PROF), these differences are likely due to random variations.

In our case, both male and female researchers who continue their careers at CSIC and apply for promotion have extensive professional trajectories. Descriptive evidence indicates that they possess comparable merits as it was already the case decades ago (Mauleón et al., 2008). This suggests that any aggregated differences in promotion probabilities may stem from other factors and processes.

While with observational research bias cannot be conclusively ruled out, our findings align with most of the research on promotion that controls for performance (Auspurg et al., 2017; Bosquet et al., 2019; Habicht et al., 2024; Lutter et al., 2022; Mairesse et al., 2020) and panel membership (Bagues et al., 2017, 2019; Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2015), and with some experimental studies (Carlsson et al., 2021; Solga et al., 2023) on hiring and promotion in academia.

Previous research in similar contexts, such as the Argentinian CONICET (D’Onofrio and Rogers, 2022) has highlighted the relevance of seniority (years in rank) in accounting for promotion. Our findings align with this, showing that promotion is often a matter of time. However, our recent data offer additional insights: promotion probabilities are influenced by seniority and gender, with an interaction effect indicating higher probabilities for females at lower seniority levels. Conversely, males exhibit much higher promotion probabilities at higher seniority levels.

It is important to acknowledge the potential positive developments and effects of gender equality policies (González Ramos et al., 2020). Encouragingly, alongside evidence of increasingly similar productivity between men and women (Wu, 2023, 2024) there are signs that gender equality policies may have influenced evaluation attitudes, helping to mitigate gender biases. This suggests that efforts to promote gender equality in the last 15 years in research environments can yield positive results.

Consistent with scientific norms, our findings indicate that candidates’ merit factors play an important role in promotion. Higher levels of citations, project leadership, patents, and other merit indicators increase the likelihood of promotion. Publications’ impact, particularly citations received, overweighs the sheer number of publications. The probability analysis shows minimal gender differences on how publications affect promotion probabilities, suggesting gender neutrality in this aspect of the evaluation process. Most importantly, we do not find evidence that men and women with similar performance have significant different promotion probabilities.

Notably, the most consistently important performance factor is the number of research projects as PI. This aligns with previous research that highlights the crucial role of funding in career progression (Bloch et al. 2014; Thelwall et al. 2023). Emphasising research projects’ leadership is relevant since promotion studies often focus solely on bibliometric factors.

Our study reveals additional influential elements beyond scientific merits. Those who are promoted typically demonstrate greater scientific achievements compared to those who are not. However, the evaluation panels face challenges in allocating the limited number of promotion positions highlighting the notion that “there are more excellent candidates than available positions”. This situation likely indicates that factors other than scientific performance could play a role in the final decisions of evaluation panels.

Specifically, the relevance of institutional proximity (Boudreau et al., 2016; Wang and Sandström, 2015) or connections (Bagues et al., 2019; Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2015, 2015) has been highlighted. If two candidates in the second evaluation phase have similar merits and past performance, having an evaluator from the own institute could be decisive in the final selection. This is not necessarily a matter of absence of merit-based evaluation, as suggested by the inbreeding literature (Horta, 2013), but rather an indication that, in the absence of substantial differences in performance, familiarity with the candidate, institutional proximity or connections become plausible explanations for the final decision.

The proximity finding raises concerns about the fairness and impartiality of the promotion process. Studies from countries like Italy, Germany or Sweden (Abramo and D’Angelo, 2020; Auspurg et al., 2017; Sandström and Hällsten, 2008) have highlighted the detrimental effects of favouritism in academic evaluations. These studies highlight the importance of addressing normative deviations in various peer review contexts.

The proportion of female evaluators, which is often used as a standard measure of equality policies, is not associated with higher promotion probabilities for women. This finding suggests that simply increasing the number of women on evaluation panels, especially in strongly male-dominated areas, may not necessarily lead to better outcomes for female candidates. Instead, such efforts may inadvertently burden already scarce women with additional evaluation tasks, consuming valuable time and potentially impacting their own career progression (Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2015).

Recent research has highlighted that evaluation panels, particularly those assessing candidates within specific disciplines often aim to prevent the concentration of resources. In our study, we observed this effect in promotion to PROF when multiple candidates from the same institute competed within the same specialty. This scenario resulted in a negative impact on promotion probabilities, counterbalancing the influence of institutional proximity, and suggesting a redistributive dynamic within panels. This effect aligns with previous findings regarding research funding allocation (Lawson and Salter, 2023).

Finally, an inequality factor arising in the promotion process stems from the discretionary allocation of positions across scientific specialties by institutional management. This practice creates varying levels of competition. While this factor does not seem to affect candidates of different gender in a different way, it does impact the initial probabilities of candidates across different fields and specialties.

This emphasizes the importance of examining not only individual-level factors but also institutional aspects of the promotion process. Analysing how discretionary decisions regarding resource allocation can perpetuate or mitigate disparities across various scientific domains is crucial for promoting fairness and equity within scientific institutions.

Despite our efforts to incorporate a comprehensive range of factors in the promotion analysis, there are some limitations and caveats to consider.

The data are derived from a single multidisciplinary organisation where teaching is not mandatory and the primary focus is on research. While this setting offers advantages for certain objectives, it may a limit the generalisation of findings to other academic contexts. Additionally, although Spanish research institutions share some commonalities to other similar large research organisations in Europe, the study is based on data from a single country.

A caveat that steams from the limitations inherent in observational research is the possibility of unobserved variables influencing the factors included in the models.

We must also acknowledge the presence of uncertainty inherent in all types of estimates. Small observational populations increase levels of uncertainty, which can affect the robustness of our findings. In the defence of the case, we have not relied on samples and have analysed the whole applicant population in the period under study.

Finally, although we included various performance indicators beyond bibliometric ones—such as projects, patents, contracts, and PhD supervision—there may still be additional evaluation criteria not captured in our study that could influence the assessment process. The complexity of criteria used by evaluators (Cruz-Castro and Sanz-Menéndez, 2021; Hug, 2024) implies the need for constant improvement of the measures in future research.

Data availability

Anonymized data supporting the research will be provided after the article publication and it will also be archived at the CSIC institutional repository (digital.csic.es) at the end of project. It also could be provided for research purposes on reasonable request.

Notes

Promotion, in Spanish “promoción interna”, is a vertical promotion. Calls are targeted for promotion inside the organization. Only members of CSIC research categories can apply.

We include, as suggested by one reviewer, the models by gender in Supplementary Information. SI-4.

Our population of reference are applicants. Previous literature has documented different patterns of application behaviour across genders. Although not the focus of this article, we have checked if women and men at CSIC apply for promotion at different rates and found non-significant differences (see Supplementary Information. SI 5).

References

Abramo G, D’Angelo CA (2020) Were the Italian policy reforms to contrast favoritism and foster effectiveness in faculty recruitment successful? Sci Public Policy 47(5):604–615. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scaa048

Abramo G, D’Angelo CA, Rosati F (2015) Selection committees for academic recruitment: Does gender matter? Res Eval 24(4):392–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv019

Abramo G, D’Angelo CA, Rosati F (2016) Gender bias in academic recruitment. Scientometrics 106(1):119–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1783-3

Aksnes DW, Kahn S, Reiling RB, Ulvestad MES (2025) Examining career trajectories of Norwegian PhD recipients: slower progression for women academics but not a leaky pipeline. Stud High Educ 0(0):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2400545

Allison PD (1999) Comparing logit and probit coefficients across group. Sociol Methods Res 28(2):186–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124199028002003

Auspurg K, Hinz T, Schneck A (2017) Appointment procedures as tournaments: gender-specific chances of being appointed as professorships. Z Fur Soziol 46(4):283–301. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2017-1016

Bagues M, Sylos-Labini M, Zinovyeva N (2017) Does the gender composition of scientific committees matter? Am Econ Rev 107(4):1207–1238. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20151211

Bagues M, Sylos-Labini M, Zinovyeva N (2019) Connections in scientific committees and applicants’ self-selection: evidence from a natural randomized experiment. Labour Econ 58:81–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.04.005

Banal-Estañol A, Liu Q, Macho-Stadler I, Pérez-Castrillo D (2023) Similar-to-me effects in the grant application process: applicants, panellists, and the likelihood of obtaining funds. RD Manag 53(5):819–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12601

Bloch C, Graversen EK, Pedersen HS (2014) Competitive research grants and their impact on career performance. Minerva 52(1):77–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-014-9247-0

Bol T, de Vaan M, van de Rijt A (2022) Gender-equal funding rates conceal unequal evaluations. Res Policy 51(1):104399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104399

Bornmann L (2011) Scientific peer review. Annu Rev Inf Sci Technol 45(1):197–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2011.1440450112

Bosquet C, Combes P, García‐Peñalosa C (2019) Gender and promotions: evidence from academic economists in France*. Scand J Econ 121(3):1020–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12300

Boudreau KJ, Guinan EC, Lakhani KR, Riedl C (2016) Looking across and looking beyond the knowledge frontier: intellectual distance, novelty, and resource allocation in science. Manag Sci 62(10):2765–2783. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2285

Box-Steffensmeier JM, Cunha RC, Varbanov RA, Hoh YS, Knisley ML, Holmes MA (2015) Survival analysis of faculty retention and promotion in the social sciences by gender. PLoS ONE 10(11):e0143093. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143093

Card D, DellaVigna S, Funk P, Iriberri N (2020) Are referees and editors in economics gender neutral?. Q J Econ 135(1):269–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz035

Card D, DellaVigna S, Funk P, Iriberri N (2021) Gender differences in peer recognition by economists (Working Paper 28942). Natl Bur Econ Res. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28942

Carlsson M, Finseraas H, Midtbøen AH, Rafnsdóttir GL (2021) Gender bias in academic recruitment? Evidence from a survey experiment in the Nordic region. Eur Sociol Rev 37(3):399–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa050

Cech EA, Blair-Loy M (2010) Perceiving glass ceilings? Meritocratic versus structural explanations of gender inequality among women in science and technology. Soc Probl 57(3):371–397. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2010.57.3.371

Ceci SJ, Kahn S, Williams WM (2023) Exploring gender bias in six key domains of academic science: an adversarial collaboration. Psychol Sci Public Interest 24(1):15–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/15291006231163179

Ceci SJ, Williams WM, & Kahn S (eds) (2018) Underrepresentation of women in science: international and cross-disciplinary evidence and debate. Front Psychol 8:2352. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88945-434-1

Cole J, Zuckerman H (1984) The productivity puzzle: persistence and change in patterns of publication of men and women scientists. Adv Motiv Achiev 2:217–258

Cole JR (1979) Fair science: Women in the Scientific Community. The Free Press

Cole S, Cole JR, Simon GA (1981) Chance and consensus in peer review. Science 214(4523):881–886. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7302566

Cruz-Castro L, Sanz-Menéndez L (2010) Mobility versus job stability: assessing tenure and productivity outcomes. Res Policy 39(1):27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.11.008

Cruz-Castro L, Sanz-Menéndez L (2021) What should be rewarded? Gender and evaluation criteria for tenure and promotion. J Informetr 15(3):101196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2021.101196

D’Onofrio MG, Rogers JD (2022) Key factors affecting the promotion of researchers of the Argentine Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET). Res Eval 31(2):188–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvab041

Danell R, Hjerm M (2013) The importance of early academic career opportunities and gender differences in promotion rates. Res Eval 22(4):210–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvt011

De Paola M, Scoppa V (2015) Gender discrimination and evaluators’ gender: evidence from Italian Academia. Economica 82(325):162–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12107

Derrick GE (2019) The Evaluators’ Eye—impact assessment and academic peer review, 1st edn. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://www.palgrave.com/fr/book/9783319636269

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission), Pépin A, Andriescu M, Buckingham S, Moungou A, Gilloz O, Collier N, Tenglerova H, Dunn K, Hoya C, Nájera L, Nicosiam D, Davies R (2024) Impact of gender equality plans across the European Research Area: Policy briefs. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxemburg. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/655676

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission) (2021) She Figures 2021: Gender in research and innovation: statistics and indicators (https://projects.research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/en/knowledge-publications-tools-and-data/interactive-reports/she-figures-2021). Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/06090,

Fox MF (2015) Gender and clarity of evaluation among academic scientists in Research Universities. Sci Technol Hum Values 40(4):487–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243914564074

Fox MF, Xiao W (2013) Perceived chances for promotion among women associate professors in computing: Individual, departmental, and entrepreneurial factors. J Technol Transf 38(2):135–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9250-2

Gelman A, Hill J, Vehtari A (2020) Regression and other stories. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (England). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139161879

González Ramos AM, Conesa Carpintero E, Pons Peregort O, Tura Solvas M (2020) The Spanish Equality Law and the gender balance in the evaluation committees: an opportunity for women’s promotion in higher education. High Educ Policy 33(4):815–833. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0103-y

Groeneveld S, Tijdens K, van Kleef D (2012) Gender differences in academic careers: evidence for a Dutch university from personnel data 1990‐2006. Equal Divers Incl Int J 31(7):646–662. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151211263487

Gumpertz M, Durodoye R, Griffith E, Wilson A (2017) Retention and promotion of women and underrepresented minority faculty in science and engineering at four large land grant institutions. PLoS ONE 12(11):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187285

Habicht I, Schröder M, Lutter M (2024) Female advantage in German sociology: Does accounting for the “leaky pipeline” effect in becoming a tenured university professor make a difference? Soz Welt 26:407–456. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783748925590-407

Horta H (2013) Deepening our understanding of academic inbreeding effects on research information exchange and scientific output: new insights for academic based research. High Educ 65(4):487–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9559-7

Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX (2013) Applied logistic regression, 3rd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken (N.J.)

Huang J, Gates AJ, Sinatra R, Barabási A-L (2020) Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117(9):4609–4616. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914221117

Hug SE (2022) Towards theorizing peer review. Quant Sci Stud 3(3):815–831. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00195

Hug SE (2024) How do referees integrate evaluation criteria into their overall judgment? Evidence from grant peer review. Scientometrics 129(3):1231–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04915-y

Imbens GW (2021) Statistical significance, p-values, and the reporting of uncertainty. J Econ Perspect 35(3):157–174

Jayasinghe UW, Marsh HW, Bond N A multilevel cross-classified modelling approach to peer review of grant proposals: the effects of assessor and researcher attributes on assessor ratings J R Stat Soc: Ser A 166(3):279–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-985X.00278

Jungbauer-Gans M, Gross C (2013) Determinants of success in University careers: findings from the German Academic Labor Market/Erfolgsfaktoren in der Wissenschaft—Ergebnisse aus einer Habilitiertenbefragung an deutschen Universitäten. Z Für Soziol 42(1):74–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2013-0106

Kahn S (2012) Gender differences in academic promotion and mobility at a major Australian University. Econ Rec 88(282):407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2012.00828.x

Kahn S, Ginther DK (2018) Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Are differences in education and careers due to stereotypes, interests, or family? In: Averett SL, Argys LM, Hoffman SD (eds) The Oxford handbook of women and the economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford (England), pp 767–798. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.13

Kwiek M, Roszka W (2022) Are female scientists less inclined to publish alone? The gender solo research gap. Scientometrics 127:1697–1735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-022-04308-7

Larivière V, Sugimoto CR (2017) The end of gender disparities in science? If only it were true… CWTS. https://www.cwts.nl:443/blog?article=n-q2z294

Lawson C, Salter A (2023) Exploring the effect of overlapping institutional applications on panel decision-making. Res Policy 52(9):104868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104868

Leahey E, Crockett JL, Hunter LA (2008) Gendered academic careers: Specializing for success? Soc Forces 86:1273–1309. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0018

Lee CJ, Sugimoto CR, Zhang G, Cronin B (2013) Bias in peer review. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 64(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22784

Lissoni F, Mairesse J, Montobbio F, Pezzoni M (2011) Scientific productivity and academic promotion: a study on French and Italian physicists. Ind Corp Change 20(1):253–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtq073

Long JS (1978) Productivity and academic position in the scientific career. Am Sociol Rev 43(6):889–908. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094628

Long JS, Mustillo SA (2021) Using predictions and marginal effects to compare groups in regression models for binary outcomes. Sociol Methods Res 50(3):1284–1320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799374

Long JS, Allison PD, McGinnis R (1993) Rank advancement in academic careers: sex differences and the effects of productivity. Am Sociol Rev 58(5):703–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096282

Lutter M, Schröder M (2016) Who becomes a tenured professor, and why? Panel data evidence from German sociology, 1980–2013. Res Policy 45(5):999–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.01.019

Lutter M, Habicht IM, Schröder M (2022) Gender differences in the determinants of becoming a professor in Germany. An event history analysis of academic psychologists from 1980 to 2019. Res Policy 51(6):104506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104506

Mairesse J, Pezzoni M (2015) Does gender affect scientific productivity. Rev Écon 66(1):65–113. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.661.0065

Mairesse J, Pezzoni M, Visentin F (2020) Does gender matter for promotion in science? Evidence from physicists in France. Rev Econ 71(6):1005–1043. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.716.1005

Marini G, Meschitti V (2018) The trench warfare of gender discrimination: evidence from academic promotions to full professor in Italy. Scientometrics 115(2):989–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2696-8

Marsh HW, Jayasinghe UW, Bond NW (2011) Gender differences in peer reviews of grant applications: a substantive-methodological synergy in support of the null hypothesis model. J Informetr 5(1):167–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2010.10.004

Marsh HW, Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel H-D, O’Mara A (2009) Gender effects in the peer reviews of grant proposals: a comprehensive meta-analysis comparing traditional and multilevel approaches. Rev Educ Res 79(3):1290–1326. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309334143

Mauleón E, Bordons M, Oppenheim C (2008) The effect of gender on research staff success in life sciences in the Spanish National Research Council. Res Eval 17(3):213–225. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820208X331676

Merton RK (1942) The normative structure of science. In: The sociology of science. theoretical and empirical investigations, (edited by NW Storer) 1973. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, pp. 267–278

Mize TD, Doan L, Long JS (2019) A general framework for comparing predictions and marginal effects across models. Sociol Methodol 49(1):152–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175019852763

Mom C, van den Besselaar P, Möller T (2022) Factors influencing the academic career—an event history analysis. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6975566

Mom C, van den Besselaar P (2022) Do interests affect grant application success? The role of organizational proximity (arXiv:2206.03255). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.03255

Mood C (2010) Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. Eur Sociol Rev 26(1):67–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

Ni C, Smith E, Yuan H, Larivière V, Sugimoto CR (2021) The gendered nature of authorship. Sci Adv 7(36):eabe4639. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe4639

OECD (2024) The state of academic careers in OECD countries: an evidence review. OECD, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/ea9d3108-en

Olbrecht M, Bornmann L (2010) Panel peer review of grant applications: What do we know from research in social psychology on judgment and decision-making in groups? Res Eval 19(4):293–304. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820210X12809191250762

Reskin BF (1976) Sex differences in status attainment in science: the case of the postdoctoral fellowship. Am Sociol Rev 41(4):597–612. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094838

Reskin BF, Bielby DD (2005) A sociological perspective on gender and career outcomes. J Econ Perspect 19(1):71–86. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330053148010

Sabatier M (2010) Do female researchers face a glass ceiling in France? A hazard model of promotions. Appl Econ 42(16):2053–2062. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701765338

Sabatier M, Carrere M, Mangematin V (2006) Profiles of academic activities and careers: does gender matter? An analysis based on french life scientist CVs. J Technol Transf 31:311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-006-7203-3

Sabatier M, Musselin C, Pigeyre F (2015) Devenir professeur des universités. Une comparaison sur trois disciplines (1976–2007). Rev Econ 66(1):37–63. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.661.0037

Sandström U, Hällsten M (2008) Persistent nepotism in peer-review. Scientometrics 74(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-0211-3

Sanz-Menéndez L, Cruz-Castro L (2019) University academics’ preferences for hiring and promotion systems. Eur J High Educ 9(2):153–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2018.1515029

Sanz-Menéndez L, Cruz-Castro L, Alva K (2013) Time to Tenure in Spanish Universities: an event history analysis. PLoS ONE 8(10):e77028–e77028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077028

Schröder M, Lutter M, Habicht IM (2021) Publishing, signaling, social capital, and gender: determinants of becoming a tenured professor in German political science. PLoS ONE 16(1):e0243514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243514

Solga H, Rusconi A, Netz N (2023) Professors’ gender biases in assessing applicants for professorships. Eur Sociol Rev 39(6):841–861. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcad007

Sonnert G, Holton GJ (1995) Who succeeds in science? The gender dimension. Rutgers University Press

Stephan PF, Levin SG (1992) Striking the mother lode in science: the importance of age, place, and time, 1st edn. Oxford University Press

Stewart P, Ornstein M, Drakich J (2009) Gender and promotion at Canadian Universities. Can Rev Socio 46:59–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2009.01203.x

Sugimoto CR, Larivière V (2023) Equity for women in science: dismantling systemic barriers to advancement. Harvard University Press

Thelwall M, Mas-Bleda A (2020) A gender equality paradox in academic publishing: countries with a higher proportion of female first-authored journal articles have larger first-author gender disparities between fields. Quant Sci Stud 1(3):1260–1282. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00050

Thelwall M, Simrick S, Viney I, Van den Besselaar P (2023) What is research funding, how does it influence research, and how is it recorded? Key dimensions of variation. Scientometrics 128(11):6085–6106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04836-w

Tien FF (2007) To what degree does the promotion system reward faculty research productivity? Br J Sociol Educ 28(1):105–123

Treviño LJ, Gomez-Mejia LR, Balkin DB, Mixon FG (2018) Meritocracies or masculinities? The differential allocation of named professorships by gender in the academy. J Manag 44(3):972–1000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315599216

van Arensbergen P, van der Weijden I, van den Besselaar P (2012) Gender differences in scientific productivity: a persisting phenomenon? Scientometrics 93(3):857–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0712-y

van den Besselaar P, Sandström U (2016) Gender differences in research performance and its impact on careers: a longitudinal case study. Scientometrics 106(1):143–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1775-3

van den Besselaar P, Sandström U (2017) Vicious circles of gender bias, lower positions, and lower performance: gender differences in scholarly productivity and impact. PLoS ONE 12(8):e0183301. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183301

van den Besselaar P, Sandström U (2019) Measuring researcher independence using bibliometric data: a proposal for a new performance indicator. PLoS ONE 14(3):e0202712. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202712

Wang Q, Sandström U (2015) Defining the role of cognitive distance in the peer review process with an explorative study of a grant scheme in infection biology. Res Eval 24(3):271–281. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv009

Weisshaar K (2017) Publish and Perish? An assessment of gender gaps in promotion to Tenure in academia. Soc Forces 96(2):529–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sox052

Williams R (2012) Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J Promot Commun Stat Stata 12(2):308–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1201200209

Wu C (2023) The gender citation gap: why and how it matters. Can Rev Sociol 60(2):188–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12428

Wu C (2024) The gender citation gap: approaches, explanations, and implications. Sociol Compass 18(2):e13189. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13189

Xie Y, Shauman KA (2003) Women in science: career processes and outcomes. Harvard University Press

Zinovyeva N, Bagues M (2015) The role of connections in academic promotions. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(2):264–292. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20120337

Acknowledgements

This paper presents some of the research results from a project commissioned by the Presidency of the CSIC and Chair of the Women and Science Commission, Eloisa del Pino, at the end of 2022. Our colleagues Catalina Martínez and Kenedy Alva were also part of team that developed the project. The research was funded by a CSIC Special Intramural Project (PIE 202210E150). This paper has also been supported by the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (PID2023-149135-I00), INNDOC project. Many people from CSIC provided support and help (José Ruiz, Eduardo Cabrerizo, Jorge Mañanas, Irene Uceda, Maria Cuesta and Carmen Mayoral). Especial thanks to Agnès Ponsati and Luis Dorado, from the CSIC Library Information Systems (URICI) that provided us with most of the bibliometric indicators (GesBIB). Other colleagues from CSIC and from outside assessed and reviewed the report: Javier Aramayona, Federico Mompeán, Cynthia Verónica Jeppesen (CONICET), Pablo Kreimer (CONICET) and Fernando Galindo-Rueda (OCDE-NESTI). The report results were officially presented at the CSIC Directors’ meeting (Salamanca, December 2023) and discussed with the CSIC Women and Science Commission (December 2023 and February 2024). Previous versions of the paper were presented at the 5th Argentinian Congress of the Social Studies of Science and Technology (CAESCyT), Bariloche (Argentina), 27-29 November 2023, in a Seminar at the Sociology Department of the Seville University, in May 21st 2024, in a session of the RN24 (science and technology) at the 16th European Sociological Association (ESA) Conference in Porto (Portugal) 27-30 August 2024, and at the 10 Atlanta Conference on Science and Innovation Policy, 14–16 May 2025. Finally, we acknowledge the important feedback to this paper from Catalina Martínez, Ulf Sandstrom, Peter van den Besselaar, Donna K. Ginther, Francesco Lissoni and Alberto Corsini. The research project report (in Spanish) is available at: Cruz-Castro, L., Martínez, C., & Sanz Menéndez, L., with the support of Clara Casado and Kenedy Alva (2023). La promoción interna en las escalas científicas en el CSIC (OEP 2016-2020): Diferencias por sexo. CSIC - Instituto de Políticas y Bienes Públicos (IPP). https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/342260.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LCC: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. CC: Software, Validation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - Original Report, Writing- Editing. LSM: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cruz-Castro, L., Casado, C. & Sanz-Menéndez, L. Merit, competition and gender: scientific promotion in public research organisations. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 779 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05102-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05102-5