Abstract

Undergraduate interpreting training programs rely heavily on high-quality textbooks to develop student interpreters’ interpreting competence. However, there is limited empirical research assessing the vocabulary of interpreting textbooks, leaving a gap in understanding their lexical demands and pedagogical effectiveness. This study addresses this gap by evaluating the English vocabulary of undergraduate interpreting textbooks from the perspectives of vocabulary load, frequency distribution, and repetition patterns. Based on a corpus of two textbooks on interpreting between Chinese and English widely used in undergraduate interpreting training programs in the Chinese Mainland, the study finds that both textbooks require student interpreter users to possess a productive vocabulary of 3000 to 5000 word families (plus words from supplementary lists). Also, both textbooks feature the highest proportion of high-frequency words, provide an opportunity to learn mid-frequency words dominated by the third 1000 word families, and present low-frequency words concerning trending topics associated with social life in both international and domestic contexts during a certain period. Moreover, they lack words repeating at least five times across book units, while words appearing in only one unit account for a high proportion. This vocabulary assessment also provides an approach to differentiate between textbooks in the abovementioned aspects. With no vocabulary list predefined in the syllabus, this corpus-based approach of textbook vocabulary assessment can empower textbook evaluation by providing quantitative evidence for textbook suitability and usability, thereby aiding interpreting textbook writers and teachers in promoting students’ language competence, subject matter knowledge, interpreting ability, and the cultivation of values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Teaching materials for foreign language learning are essential teaching resources, a reflection of the landscape of foreign language education. However, most studies on foreign language teaching materials center around materials development instead of evaluation, and those on evaluation are overwhelmingly qualitative, signaling a severe lack of quantitative assessment in this field (Pan and Zhu, 2022; Li et al., 2023). As interpreter training programs widely offered by tertiary institutions progress continuously, interpreting textbooks have witnessed a surge in publication (Sheng, 2024). However, limited research on interpreting textbooks concentrates on qualitative analysis of content and design. With developments in the use of corpora for language assessment (Park, 2014; Coombe and Gitsaki, 2016; Nelson, 2022), the present study aims to present a corpus approach to evaluating interpreting textbooks by assessing the appropriateness of textbook vocabulary.

Literature review

Language knowledge in interpreter education and interpreting textbooks

Interpreter education is aimed at improving student interpreters’ interpreting competence, which encompasses several sub-competences, including language knowledge, subject matter knowledge, and interpreting skills (Russo, 2011; Gile, 2009, pp 8–9; Dimitrova and Tiselius, 2016). As studies in this field focus on improving students’ interpreting skills, limited attention has been paid to their language knowledge, let alone such knowledge provided in interpreting textbooks. Language knowledge, often referred to as bilingual sub-competence in interpreter training programs, serves as a foundational prerequisite for the development and application of other sub-competences (Gile, 2009, p 8). Language knowledge is considered various kinds of knowledge about language in the user’s memory (Bachman and Palmer, 1996). Cai et al. (2015) argued that L2 proficiency is the most important predictor of the development of interpreting competence in unbalanced beginner student interpreters. However, Li (2001) pointed out that the importance of language knowledge is unduly played down in interpreter training programs. He argued that students’ bilingual competence is inadequate for them to study interpreting immediately upon entering the program and might be partially responsible for their slow improvement in interpreting competence throughout the program. Many difficulties that student interpreters encounter do not stem from a lack of interpreting skills but from a deficiency in language knowledge (Yao, 2017). Therefore, for undergraduate interpreter training programs, the primary focus should be on enhancing language knowledge, while the secondary focus should be on skill development (Liu, 2011).

Interpreting textbooks, as a significant source of various kinds of knowledge for classroom instruction and a major factor in shaping interpreting pedagogy, have been increasingly investigated by interpreting scholars, who acknowledge that “choosing the right materials is one of the greatest challenges in effective interpreter training” (Setton and Dawrant, 2016). Many studies on interpreting textbooks pay attention to assessing speech difficulty in terms of language (Pöchhacker, 2004). For example, Huang and Bao (2016) pointed out that speech difficulty can be affected at the lexical level by the quantity and occurrence of low-frequency words, technical terms, proper names, abbreviations, etc. However, speech difficulty only measures the difficulty of understanding a text. Other factors, such as interpretability and difficulty of processing under time and cognitive constraints of interpreting, as well as their interactions, also need to be taken into account when determining the difficulty of a task offered in interpreting textbooks (Setton and Dawrant, 2016). Despite a growing interest in investigating multiple factors affecting language used in individual interpreting tasks, only a few studies have explored language knowledge presented through a whole interpreting textbook. For example, Li (2019) examined 32 business interpreting textbooks and found that most competencies, including language knowledge, are weakly presented in those textbooks and that most pedagogical principles are not well applied. Li argued that this inadequacy may render students inadequately assisted in acquiring competencies. Flores (2019) proposed a framework of reference for analyzing and developing English for translation and interpreting (ETI) materials by examining the only commercially available ETI materials in Spain. The study found that linguistic competence is among the most widely developed competencies in the materials, but the extent to which the competence is fostered is unknown. Sheng (2024) investigated one hundred and 92 interpreting textbooks published in the Chinese Mainland and highlighted the challenge of materials design in balancing language knowledge and other types of knowledge for different levels of interpreter training. Aside from these contributions, more in-depth, empirical studies on language knowledge embedded in interpreting textbooks are needed to fill the gap in understanding how knowledge as such is integrated and presented in such textbooks to support interpreter education.

Vocabulary assessment in textbooks

As an important aspect of language knowledge, vocabulary is at the forefront of the assessment of language knowledge, reflected in textbooks. For one thing, vocabulary forms the foundation of the content of language textbooks and classroom activities, so evaluation of vocabulary is an inseparable part of influential theories and frameworks for evaluating foreign language textbooks (e.g., Breen and Candlin, 1987; Hutchinson and Waters, 1987; McDonough et al., 2013). For another, the vocabulary of a textbook is an important factor that affects the accomplishment of teaching objectives of the language curriculum. Research on English vocabulary in textbooks has attracted consistent attention since the early stages of material analysis and evaluation. Such key areas as vocabulary load, frequency, and repetition are widely recognized as essential factors in determining the effectiveness of vocabulary acquisition (e.g., Nation, 2001; Szudarski, 2018; Webb, 2020). They have been constantly researched in the context of various EFL, ESP, and EAP textbooks, but have received scarce attention regarding interpreting textbooks that involve English as a working language.

Vocabulary load

The vocabulary load of a textbook refers to the vocabulary needed by a student to fully understand the materials of the textbook. It can help assess whether the vocabulary requirement and distribution accord with students’ vocabulary size to assist their vocabulary acquisition. Vocabulary load depends on the lexical coverage of a text, which refers to the percentage of words covered by items from a word list in a corpus (Nation and Waring, 1997). Such English wordlists include the general service list (GSL) (West, 1953), the academic word list (AWL) (Coxhead, 2000), and the BNC/COCA frequency lists (Nation, 2016), which consist of twenty-five 1000-word families. A word family is a unit that includes both the base form of a word (e.g., work) and its inflections (e.g., worked, works), as well as its derivations (e.g., worker) (Webb, 2020, p 83). The lexical coverage of 95% is the minimal threshold that enables students to gain acceptable comprehension with assistance, and 98% is optimal for making them independent readers (Nation, 2001; Laufer, 2013). Arguably, for textbooks oriented toward language learning, students need a lexical coverage of 95%; for textbooks designed for sense-making and with high requirements for understanding, such as specialized ELT textbooks, 98% is desirable.

Studies on the vocabulary load of foreign language textbooks are abundant, e.g., secondary school textbooks (Sun and Dang, 2020), ESP textbooks such as college engineering textbooks (Hsu, 2014) and college physics textbooks (Stamatović, 2020), and EAP textbooks (Reppen and Olson, 2020; Lu and Dang, 2022). In foreign language education, students usually attribute the main difficulty in understanding and using a foreign language to a lack or low quality of vocabulary knowledge (Nation, 2013). Therefore, studies in this line commonly advise textbook writers to take into account students’ vocabulary knowledge level to raise the possibility of their comprehension of materials, so as to improve materials’ applicability and adaptability to support meaningful learning.

Frequency

Frequency is a key factor of vocabulary acquisition, which can both indicate essential vocabulary and affect the transfer from lexical input to vocabulary learning as well as language processing (Ellis, 2002). Nation (2006), based on the frequency levels of each of 1000 word families in BNC/COCA, categorized vocabulary into high-frequency, mid-frequency, and low-frequency words. High-frequency words are words from the first and second 1000 word families (such as the most frequent lexical words and function words), accounting for over 80% of written texts and nearly 95% of spoken texts. High-frequency words are regarded as essential vocabulary and a top priority in foreign language teaching, and learners need to learn them as early as possible to increase the efficiency of their learning effort (Gu, 2019). Medium-frequency words are from the third to the ninth 1000-word families. Learners may pay more attention to mid-frequency words after they have acquired high-frequency words. Although mid-frequency words require more effort to acquire, they are essential for learners to effectively use a foreign language (Szudarski, 2018, p 57). Low-frequency words are made up of the tenth 1000 word families and beyond (e.g., technical terms), which can be ignored when they are not essential for comprehension (Laufer, 2013).

Studies on the distribution of high-, mid-, and low-frequency words have been conducted in relation to EFL textbooks (Sun and Dang, 2020; Yang and Coxhead, 2020), Intensive Reading textbooks for English majors (Song, 2016), ESP textbooks (Hsu, 2014; Bi, 2020), and EAP textbooks (Skoufaki and Petrić, 2021; Lu and Dang, 2022; Huang and Wible, 2024). These studies attempt to reveal the textbook’s selection of or emphasis on words at different frequency levels to offer guidance for vocabulary acquisition, as well as to discover reasons why the presentation of words causes difficulties for learners (Coxhead and Boutorwick, 2018).

Repetition

Vocabulary acquisition is a process of knowledge accumulation, and its progress and outcome depend on the exposure and reoccurrence of words. The repetition of vocabulary increases the opportunity for learners to develop receptive knowledge into productive knowledge, thereby promoting the comprehensive development of vocabulary knowledge (Webb, 2007). As for the design of textbook content, Cunningsworth (1995) emphasized that the repetition of vocabulary is a primary factor for consideration. However, there is no consensus on the ideal number of recurrences in textbooks. Waring and Nation (2004) argued that a word must be repeated at least five times across different texts to be acquired. Webb (2007) stated that more than ten recurrences of a word are necessary to fulfill the need for acquiring all lexical knowledge of the word, while Reynolds et al. (2015) found that if the material is essential and engaging to students, only three exposures of a word are sufficient for them to grasp its meaning.

By examining the repetition of words in EFL textbooks and scientific English textbooks for EFL learners, Zhu and Xu (2014) found that the percentages of words repeated more than five times are not high, at 32.2% and 15.2% respectively. Wang and Xu (2013) also found that the repetition rate of vocabulary in college EFL textbooks is low. Sun and Dang (2020) suggested that the repetition of high-frequency words should be maximized for high school students and that knowledge of the most frequent words would support and motivate them when learning less frequent words. As for EAP textbooks, Skoufaki and Petrić (2021) found that the repetition rate of over one-third of the academic words is too low for recall vocabulary knowledge to develop incidentally in the materials. It seems common for a large number of words to appear only once in a textbook (Nation, 2013). Achieving an adequate rate of word repetition may be a challenge for both the materials design on the part of textbook writers and the vocabulary acquisition on the part of EFL learners.

Overall, research on assessing English vocabulary in various textbooks has widely applied corpus methods to provide empirical evidence for textbook assessment (Liu et al., 2022; Nelson, 2022; Van Parys et al. 2024). However, vocabulary in interpreting textbooks is not researched as dedicatedly and thoroughly as a major constituent of language knowledge, since language knowledge has received insufficient attention for the evaluation of interpreting textbooks. Hence, it is worthwhile to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the English vocabulary in interpreting textbooks in the key areas highlighted above, particularly when English serves as a passive language of students enrolled in interpreter training programs. Such an assessment would not only shed light on the rationality of vocabulary selection and presentation in an interpreting textbook but also enhance the supportive and mediating function of such textbooks in developing student interpreters’ language knowledge and advancing their overall interpreting competence. Therefore, the present study applies a self-built corpus of two Chinese–English interpreting textbooks widely used in the Chinese mainland to analyze their English vocabulary, in an attempt to answer the following three questions:

-

(1)

What is the vocabulary load of the interpreting textbooks?

-

(2)

How are high-, mid-, and low-frequency words distributed in the interpreting textbooks?

-

(3)

How is the repetition of words across units designed in the interpreting textbooks?

Data and method

Corpus

The two textbooks investigated in the present study are “A Foundation Coursebook of Interpreting Between English and Chinese” published by Higher Education Press in 2007 and “Challenging Interpreting: A Coursebook of Interpreting Skills” published by Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press in 2014 (hereinafter referred to as Textbook A and B respectively) in the Chinese mainland. The reasons for choosing the two textbooks are threefold. First, the two textbooks are chosen as China’s National Planned Textbooks for the 11th Five-Year and 12th Five-Year periods, respectively, making them representative of high-quality interpreting textbooks. Second, both textbooks specify in the foreword undergraduate English majors as part of their target audience and their intended learning outcomes as comprehensively enhancing the interpreting competence of undergraduate student interpreters. Third, their units are similarly structured around a series of interpreting skills (such as memory, note-taking, and coping tactics). For broader applicability, the present study only examines the English vocabulary that is involved in the textbooks’ English–Chinese interpreting exercises as the source language and Chinese–English exercises as the target language.

Analysis

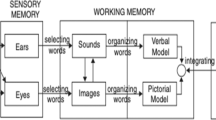

The data analysis is conducted in the following steps. First, we build a corpus of the two interpreting textbooks mentioned above. After scanning the textbook materials, we carry out text cleaning and preprocessing. Notably, we add spaces before and after hyphens to split hyphenated compound words into separate words; additionally, we do not distinguish between homographs.

Next, we investigate the vocabulary load and distribution of words at different frequency levels of the textbooks. To do so, we select the commonly chosen BNC/COCA frequency lists (Nation, 2016) containing twenty-five 1000 word families, use the software Range to mark each word with the word family to which the word belongs, and use the software AntWordProfiler to measure the coverage rate of each of 1000 word families in the textbooks. Besides the twenty-five 1000 word families, the BNC/COCA frequency lists also include four supplementary lists as follows: (1) a list of proper nouns; (2) a list of marginal words, including interjections and letters in the alphabet; (3) a list of compound words; and (4) a list of acronyms (Nation, 2016, p 132). Additionally, we count words that did not appear in either the word families’ lists or the supplementary lists as words from the supplementary lists.

Then, we set out to measure vocabulary repetition based on the lemma proposed by Nation (2006). We use the software Wordsmith 5 for lemmatization and AntWordProfiler to obtain data about the word family, frequency, and repetition of a lemma across units. Undoubtedly, the number of lemmas is bigger than that of word families but smaller than that of types and tokens (see Table 1). After that, the chi-square test is employed to assess the difference in the frequency distribution of words, lemmas, etc. between the two textbooks (the significance level was set at 0.001).

Finally, based on the quantitative results, we qualitatively analyze the lexical features of the interpreting textbooks that reflect vocabulary selection and presentation and explore similarities and differences between the two textbooks.

Results and discussion

Vocabulary load

Essential vocabulary

It is found that student interpreters need to know words from the first 3000 or 5000 word families plus supplementary lists (including proper nouns, compound words, acronyms, etc) to reach a 95% or 98% coverage of both interpreting textbooks (see Table 2). This result about the 95% vocabulary coverage is consistent with that for EFL textbooks for high school students (Sun and Dang, 2020) and for New Concept English textbooks (Yao, 2017; Yang and Coxhead, 2020), but considerably smaller than 5000 word families for college engineering textbooks (Hsu, 2014), 8000 word families for college physics textbooks (Stamatović, 2020) and 4000 word families for EAP textbooks (Lu and Dang, 2022). Also, the requirement is found to be lower for student interpreters to reach a 98% coverage of the interpreting textbooks than for each of those textbooks mentioned above. Given that the National Syllabus for English Majors (hereinafter referred to as the Syllabus) issued by China’s Ministry of Education requires that college English majors should recognize 4000–6500 words in the first two years of college, these results seem to indicate that student interpreters, who start their interpreting training in the third year of college, may have little difficulty in reading and understanding English words written in interpreting textbooks based on their receptive vocabulary. Yet it is difficult to decide whether their vocabulary size can meet the requirement for understanding English utterances through listening. Meanwhile, they may encounter great difficulty in using the first 3000 to 5000 word families (around 19000 to 28000 words) when interpreting from Chinese into English, as their productive vocabulary knowledge often lags behind their receptive counterpart.

Therefore, this study recommends that interpreting textbooks should limit the vocabulary load for reaching a 98% coverage to the first 3000 word families for student interpreters taught at the initial stage of interpreter training. This can help interpret textbooks fit in with students’ vocabulary size to make learning happen, improve their learning autonomy and independence by raising their confidence as beginning learners (Tomlinson, 2012), and help them divert attention from lexical knowledge to meaning processing and sense-making, fully preparing them for upcoming skill-oriented interpreting practice.

Supplementary lists

According to Table 2, the coverage of supplementary lists, above 5% for both textbooks, shows if student interpreters fail to get assistance for these words they can hardly reach the acceptable comprehension of the materials in each unit, which contain 49 and 45 lemmas respectively that students usually need to tackle within two teaching hours each week. This indicates that the users of Textbook A rely more heavily on words from the supplementary lists than those of Textbook B, and supplementary lists play a significant role in students’ comprehension of textbooks (Sun and Dang, 2020; Yang and Coxhead, 2020).

Further, both textbooks allocate, in the supplementary lists, the highest proportion of proper names as widely used across units, particularly those denoting countries and regions, which account for around 30% of words from the supplementary lists. The heavy use of proper names indicates an emphasis on materials about communication and exchanges beyond regional and national boundaries. It also illustrates the textbook writer’s preference for materials promoting the country’s and its major cities’ roles in international communication, which is advocated by ideological and political education in Chinese universities (Zhao et al., 2023). Moreover, proper names appear more frequently than abbreviations and compounds. Proper names and compounds (e.g., online and worldwide in Textbook A and inflow and outbreak in Textbook B) are more commonly used to discuss general topics, whereas abbreviations are used more frequently in units dealing with specialized subject matters. In light of this, the teacher may need to clarify abbreviations where they appear densely in a single unit (e.g., FTA, TPP, WMPs, FDI in Textbook B) or provide students with additional background information accordingly.

Though occupying a small proportion, words from the supplementary lists reflect the textbook’s emphasis on concepts about social life, national development, and cultural exchanges (e.g., matchmaking, globetrotter, needlework), demonstrating the timeliness and novelty of selected materials. Besides, the frequent use of proper names and abbreviations, while helping advance student interpreters’ language and world knowledge, challenges their ability to apply memory, attentive listening, codeswitching skills, coping tactics, etc., to tackle these terms. Therefore, the teacher needs to strike a balance between promoting knowledge and competence and advancing interpreting skills.

Distribution of high-, mid- and low-frequency words

High-frequency words

As shown in Table 3, the lexical coverage of words at different frequency levels is found to rank as follows: high-frequency words (over 80%), mid-frequency words (over 10%), and low-frequency words (around 0.4%), excluding words from the supplementary lists. The result that high-frequency words have the highest coverage in textbooks is echoed by Nation (2001), who proves that high-frequency words occupy over 80% of written texts, indicating that the materials for interpreting textbooks resemble written discourse in terms of register. In addition, high-frequency words have lower coverage in interpreting textbooks than in EFL textbooks used in high schools (Yang and Coxhead, 2020) and in those taught for college English majors (over 85%) (Song, 2016), but approach that in college engineering textbooks (Hsu, 2014). The similarity that interpreting textbooks bear to ESP textbooks shows that interpreting textbooks both require adequate high-frequency words to serve as essential vocabulary to improve student interpreters’ vocabulary knowledge and contain those of lower frequency to convey diverse subject matter knowledge of the discipline involved. All these seem to indicate interpreting textbooks’ proximity to written instead of spoken discourse, which may cause students difficulty in processing dense and formal information and producing delivery of the conversational nature required for spoken interaction. Correspondingly, teachers could consider integrating exercises that encourage students to repeatedly use high-frequency words across various contexts, allowing students to encounter and apply these words in different registers and situations. Teachers could also leverage supplementary materials, such as flashcards, vocabulary quizzes, and digital applications, to provide students with further opportunities to enhance their productive knowledge of high-frequency vocabulary outside the classroom.

In comparison, Textbook A has a significantly lower rate of high-frequency words and their lemmas than Textbook B (χ2 = 13.408, p = 0.000), yet has a significantly higher rate of words from the supplementary lists and their lemmas than Textbook B (χ2 = 30.940, p = 0.000). As the difficulty of its words from the supplementary lists is relatively manageable, mainly concerned with general topics and concepts or easy terminology, Textbook A demonstrates the writer’s stronger intention to seek a balance between the presentation of vocabulary knowledge and subject matter knowledge. Though the two textbooks share approximately 70% of words at this level, they are considerably different in terms of the frequencies of those shared content words. For example, the top five most frequent high-frequency words in Textbook A are world, development, country, year, and people, and they are energy, year, country, world, and food in Textbook B. So, comparing high-frequency words helps indicate the similarities and differences between interpreting textbooks in selecting major topics and designing their specialized nature.

Mid-frequency words

Based on Tables 2 and 3, the lexical coverage rates of mid-frequency words of the two textbooks (11.9% and 12.03%) are not significantly different (p = 0.548). Both results are higher than 8.42% in New Concept English textbooks (Yang and Coxhead, 2020) and lower than 17.17% in college engineering textbooks (Hsu, 2014). This finding shows that student interpreters may find it more difficult than students of English for general purposes but easier than students of ESP to handle nearly 40% of all lemmas with only 10% of the textbook materials. Additionally, the lexical coverage rates of mid-frequency words reach around one-seventh of those of high-frequency words but almost three-fourths of those of high-frequency lemmas in both textbooks. Yet, 80% of the mid-frequency words come from the third 1000-word families, indicating that those words are among the most frequently used mid-frequency ones. These findings seem to argue that both textbooks attempt to expose students to frequently used mid-frequency words through limited materials. As such, they aim to extend students’ vocabulary knowledge to cover more words at lower frequency levels (Yang and Coxhead, 2020), thus improving their ability to use English as a foreign language (Szudarski, 2018, p 57). Moreover, the shared mid-frequency words account for around 50% in both textbooks, far lower than that of the shared high-frequency ones, suggesting that interpreting textbooks differ more widely in lexical selection in terms of the mid-frequency band.

Low-frequency words

Results show that the low-frequency words occupy a small proportion of lexical coverage in both textbooks, slightly lower than 0.58% in New Concept English textbooks (Yang and Coxhead, 2020) and far lower than 2.11% in college engineering textbooks (Hsu, 2014). This may prove that low-frequency words play a marginal role in textbooks. Also, the shared lemmas of low-frequency words account for only 10% of all lemmas at this frequency level in both textbooks, suggesting that the biggest difference in lexical selection between the two textbooks rests in the low-frequency band. Further, low-frequency words, usually characterized by long word length (e.g., broadband, prudential, chopstick, and chrysanthemum), are scattered in a limited number of units, with most of them occurring within only one unit. For example, out of 126 low-frequency words in Textbook A, only one word (i.e., unremitting) occurs in three units; out of 95 low-frequency words in Textbook B, only eight words occur in three units (i.e., megacity, capita, mindset, blogger, geopolitical, hydropower, rollercoaster, and onshore). These low-frequency words often pertain to contentious topics related to national development and social life. Teachers should not ignore them as a whole because they could help widen students’ breadth of vocabulary knowledge, which may benefit students from the complementarity of breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge (Schmitt and Schmitt, 2014).

Moreover, the presentation of low-frequency words affects students’ acquisition thereof. When these words occur in contexts packed with high-frequency ones, students could infer their meanings based on those contexts or draw on coping tactics. Consequently, when some low-frequency words co-occur with others at this level, such as words from supplementary lists or words of long length, students may find them fairly difficult to understand. In Example (1) of Textbook A, low-frequency words resplendence and clarion (from the 11th and 12th 1000 word families) occur with words from supplementary lists billowy and digitalization in neighboring sentences. In Example (2) of Textbook B, low-frequency words byproduct and megacities (from the 11th and 19th 1000 word families) occur after a sentence containing mid-frequency words of rather long word length, i.e., urbanization, reshaping, and landscape. This study argues that raw materials need to be adapted to improve the accessibility of the context in which low-frequency words occur. Besides, the teacher may teach students skills at using contextual clues to infer their meanings, offering more opportunities for incidental acquisition of such words in class. By so doing, adapted materials can become pedagogically more effective in advancing vocabulary acquisition by student interpreters without outweighing their major role of promoting skill-centered practice.

-

(1)

Dear friends, the {7}fruitful past year has passed already and we are working {2}energetically for the {11}resplendence of the year 2005. Now the {12}clarion for the {2}battle has blown. In face of the billowy {2}tide of digitalization, we have confidence in and have {2}skill in seizing the {2}favorable {2}opportunity.

-

(2)

It is clear that urbanization is {7}reshaping the landscape of the world. As a {11}byproduct of it, more and more {19}megacities are being {2}produced. Interestingly, they are now more often found in the {2}developing world.

Repetition

As shown in Table 4, the lemmas of words that appear only once, or do not repeat, occupy the largest proportion (around 50%) of all lemmas; those of words that appear twice to five times, or repeat once to four times across units, the second largest (around 35%); and those of words that appear six times and more, or repeat at least five times across units, the smallest (around 15%). The proportion of the lemmas of words that repeat at least five times across units in the interpreting textbooks is considerably smaller than those of such lemmas of College English Test Band 4 and Band 6 vocabularies designated for Chinese college English textbooks used by non-English majors (about 20–37%) (Wang and Xu, 2013). These findings illustrate that in interpreting textbook materials that aim for skills at meaning transfer, about half of the lemmas do not reoccur frequently, which makes the repetition of vocabulary a challenge for both textbook writers to devise vocabulary and users to acquire vocabulary (Nation, 2013). Also, the large proportion of lemmas that appear only once highlights the necessity for the teacher to offer more opportunities for students to acquire them. For example, the teacher can provide supplementary materials to facilitate their deliberate acquisition, draw students’ attention to them during pre-task preparation, or devise activities to enhance their acquisition (Nation and Webb, 2011).

Words that repeat at least five times across units

Results from Table 4 show that the lemmas of words that occur more than six times or repeat at least five times across units have a significantly larger share in Textbook A (16.2%) than in Textbook B (13.1%) (χ2 = 34.944, p = 0.000). Specifically, the lemmas of words that repeat at least five times in Textbook A, be it high-, mid-, or low-frequency words, all occupy larger shares than those in Textbook B. This finding seems to indicate that Textbook A offers its users more exposure to words of all frequency levels, thereby providing its users with better chances to enlarge their vocabulary. Throughout the two textbooks, high-frequency words repeat nearly ten and eight times, and mid-frequency words reoccur twenty and twenty-seven times on average. This shows that in both textbooks, mid-frequency words recur at a relatively desirable rate in comparison with high-frequency ones (Webb, 2007). Furthermore, among high-frequency words repeating at least five times, Textbook A contains nine unique lemmas absent from Textbook B, whereas Textbook B has only one (i.e., cut) not found in Textbook A. A similar pattern holds for mid-frequency words meeting the same repetition threshold in both textbooks. Such comparisons help reveal that Textbook A is equipped with more diversified subject matters across units, while Textbook B concentrates on such subject matters as economy and trade and highlights figure-switching exercises (e.g., the word cut frequently occurs in such exercises). Teachers selecting between the two textbooks should note that Textbook A could benefit its users more from exposure to a comprehensive vocabulary (Webb, 2007), whereas Textbook B could do that more by developing skills in handling data-intensive messages.

Words that repeat once to four times across units

The proportion of lemmas of high-frequency words of this category in Textbook A (17.8%) is significantly lower than that in Textbook B (21.0%) (χ2 = 13.980, p = 0.000) (see Table 4). Although repeated about six times on average in all units, high-frequency words in this category are not evenly distributed across units in both textbooks. Particularly, some high-frequency words repeat tens of times in only one unit but occur scarcely in others (such as film, tourism, and instrument in Textbook A, and gas, safety, and bank in Textbook B). These repeated words are usually pertinent to the subject matter of the unit, so encountering them three times or more may be sufficient for students to acquire their meanings. (Reynolds et al., 2015). However, excessive repetition of these words, occurring dozens of times within a single unit, may considerably reduce opportunities for exposure to other words, whether relevant or irrelevant to the subject matter. This finding suggests that students require repeated exposure to words across varied contexts and at regular intervals throughout different units. As units progress, increasingly sufficient encounters with these words could create optimal conditions for acquisition. Nonetheless, a demanding requirement for interpreting textbook writers is not to merely increase the repetition rate but to seek a balance between the design of vocabulary repetition and the deployment of diversified subject matter knowledge throughout units.

Words that only occur within one unit

According to Table 4, the proportion of lemmas of words from supplementary lists that only occur within one unit in Textbook A is significantly higher (11.5%) than that of Textbook B (8.5%) (χ2 = 20.513, p = 0.000). Such words in Textbook A include abbreviations that occur over twenty times within a single unit (e.g., PBC, ASEAN, and RMB). Fortunately, those abbreviations are relatively manageable in terms of difficulty because they are not highly technical. In contrast, most abbreviations that recur over ten times within one unit in Textbook B are technically loaded (e.g., TPP, WMPS, FTAS, and RCEP), demanding guidance or background information to be provided for assisting acquisition.

Moreover, in the two textbooks, lemmas of words from supplementary lists that appear only once total 377 and 241, respectively, taking up nearly 70% of lemmas of words from supplementary lists that only appear within one unit. In addition to proper names, abbreviations, and compounds, words from supplementary lists that appear only once tend to focus on themes related to the nation’s social and cultural life. For example, a unit of Textbook A with the subject matter of arts contains words relating to musical instruments such as Bianzhong (a classical Chinese serial bell) and Chinese emperors such as Qianlong (an emperor of the Qing dynasty). One unit with the subject matter of food security in Textbook B has brand names such as Yili and Yashili (milk powder brands in China). These words may not be considered by students as essential vocabulary, so their acquisition may not be guaranteed by the two textbooks. But these words usually relate to concepts relevant to traditional culture and values, social lifestyles, and national strength, whose acquisition can contribute to the knowledge needed to cultivate students’ national and cultural identity and foster their confidence in disseminating their own culture. Given this, the teacher could play a due role in ideological and political education by increasing students’ awareness and efforts toward those words and facilitating their deliberate or incidental acquisition.

Conclusion

Drawing on a corpus approach, the present study assesses the English vocabulary of major interpreting textbooks used in colleges and universities in China from the perspective of vocabulary load, profile of frequency levels, and repetition. The results reveal that the English vocabulary load of 3000 word families might be challenging for student interpreters on account of their lack of productive vocabulary knowledge and English as their passive language. The findings could inform syllabus design and textbook compilation by suggesting that the vocabulary load introduced in the initial stages of the course should be kept at a more manageable level and gradually increased as students’ proficiency and skills improve. The results also manifest the commonalities and differences in vocabulary requirement, selection, and presentation between the two textbooks. The findings can be attributed to the characteristics of the two textbooks with respect to the diversity and contemporaneity of the materials selected, the breadth and technicality of vocabulary knowledge, as well as the selection of subject matters and words relevant to culture and national life. The comparison of the textbooks could help inform the teacher’s textbook selection and provide valuable pedagogical insights. Teachers using Textbook A might expect students to develop a broader range of world knowledge and subject matter expertise, while those using Textbook B could aim for students to gain greater familiarity with focused topics and specialized terminology. This contrast points to the importance of aligning textbook choice with specific teaching objectives and the needs of student groups.

With no vocabulary lists proposed in the syllabus of undergraduate interpreter training programs, the significance of the corpus method for assessing the English vocabulary of interpreting textbooks rests in its effectiveness in providing quantitative measurements of the adaptability of textbooks to the level of vocabulary knowledge and the demands for and characteristics of vocabulary acquisition of different student groups (i.e., beginner, intermediate, and advanced learners) or those at different learning stages. Thus, the approach can help teachers effectively identify learners’ needs and difficulties, guide deliberate or incidental vocabulary acquisition, design tailor-made exercises and tasks, provide learning aids, and adapt textbook materials. Additionally, it assists textbook writers in gaining a comprehensive understanding of the vocabulary appropriateness of the materials, facilitating revisions and improvements for future editions, taking into account the varying requirements of intended users. All these advantages could contribute to promoting student interpreters’ language knowledge and ultimately interpreting competence through enhancing their vocabulary knowledge. Equally importantly, they could facilitate the role of materials in cultivating students’ values and outlooks, serving as a reference for writing student-oriented teaching materials advocated by ideological and political education in Chinese universities (Zhao et al., 2023). The limitations of this study include the limited corpus size due to a small number of textbooks under study, and that the presentation of the depth of vocabulary knowledge has not been taken into account. Future studies may investigate more parameters for vocabulary assessment, such as lexical richness and difficulty, based on a large corpus of interpreting textbooks.

Data availability

Data would be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Bachman LF, Palmer AS (1996) Language testing in practice: designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bi J (2020) How large a vocabulary do Chinese computer science undergraduates need to read English-medium specialist textbooks? Engl Specif Purp 58:77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.01.001

Breen M, Candlin CN (1987) Which materials? A consumer’s and designer’s guide. In: Sheldon LE (ed) Elt textbooks and materials: Problems in evaluation and development. Modern English Publication, London, pp 13–28

Cai R, Dong Y, Zhao N et al. (2015) Factors contributing to individual differences in the development of consecutive interpreting competence for beginner student interpreters. Interpreter Translator Train 9(1):104–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2015.1016279

Coxhead A (2000) A new academic word list. TESOL Q 34(2):213–238

Coxhead A, Boutorwick TJ (2018) Longitudinal vocabulary development in an emi international school context: Learners and texts in eal, maths, and science. TESOL Q 52(3):588–610

Cunningsworth A (1995) Choosing your coursebook. Macmillan Heinemann, Oxford

Dimitrova BE, Tiselius E (2016) Cognitive aspects of community interpreting: Toward a process model. In: Martín RM (ed) Reembedding translation process research. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp. 195-214

Ellis NC (2002) Frequency effects in language processing: a review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Stud Second Lang Acquis 24(2):143–188. 10.1017.S0272263102002024

Flores JAC (2019) Analysing English for translation and interpreting materials: skills, sub-competences and types of knowledge. Interpreter Translator Train 15(3):326–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399x.2019.1647920

Gile D (2009) Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, pp 8–9

Gitsaki C, Coombe C (eds) (2016) Current issues in language evaluation, assessment and testing: Research and practice. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge

Gu PY (2019) Strategies for learning vocabulary. In: Webb S (ed) The routledge handbook of vocabulary studies. Routledge, London, pp 271–287

Hsu W (2014) Measuring the vocabulary load of engineering textbooks for EFL undergraduates. Engl Specif Purp 33:54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2013.07.001

Huang H-Y, Wible D (2024) Situating eap learners in their disciplinary classroom: how Taiwanese engineering majors ‘read’ their textbooks. J Engl Specif Purp 74:85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2024.01.003

Huang X-J, Bao C-Y (2016) Exploration into the difficulty of materials for teaching consecutive interpreting. Chin Transl J 37(1):58–62

Hutchinson T, Waters A (1987) English for specific purposes: a learning-centred approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Laufer B (2013) Lexical thresholds for reading comprehension: what they are and how they can be used for teaching purposes. TESOL Q 47(4):867–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.140

Li D (2001) Language teaching in translator training. Babel 47(4):343–354. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.47.4.05li

Li J, Gao X, Cui X (2023) Language teachers as materials developers. Relc J 54(3):881–889

Li X (2019) Analyzing translation and interpreting textbooks: a pilot survey of business interpreting textbooks. Transl Interpret Stud 14(3):392–415. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.19041.li

Liu H (2011) Stages in the development of translation competence and its pedagogical research. Chin Transl J 32(1):37–45

Liu Y, Zhang LJ, May S (2022) Dominance of Anglo-American cultural representations in university English textbooks in China: A corpus linguistics analysis. Lang, Cult Curric 35(1):83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2021.1941077

Lu C, Dang TNY (2022) Vocabulary in eap learning materials: what can we learn from teachers, learners, and corpora? System 106:102791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102791

McDonough J, Shaw C, Masuhara H (2013) Materials and methods in elt: A teacher's guide. John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex

Nation ISP (2001) Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nation ISP (2006) How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? Can Mod Lang Rev 63(1):59–82

Nation ISP (2013) Teaching and learning vocabulary. Heinle Cengage Learning, Boston

Nation ISP (2016) Making and using word lists for language learning and testing. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Nation ISP, Webb S (2011) Content-based instruction and vocabulary learning. In: Hinkel E (ed) Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Routledge, New York/London, pp 631–644

Nation P, Waring R (1997) Vocabulary size, text coverage and word lists. In: Schmitt N, McCarthy M (eds) Vocabulary: description, acquisition pedagogy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 6–19

Nelson M (2022) Corpora for English language learning textbook evaluation. In: Jablonkai RR, Csomay E (eds) The routledge handbook of corpora and English language teaching and learning. Routledge, New York/London, pp 147–160

Pan MX, Zhu Y (2022) Researching English language textbooks: a systematic review in the Chinese context (1964–2021). Asian-Pac J Second Foreign Lang Educ 7(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00156-3

Park K (2014) Corpora and language assessment: the state of the art. Lang Assess Q 11(1):27–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2013.872647

Van Parys A, De Wilde V, Macken L et al. (2024) Vocabulary of reading materials in English and French l2 textbooks: a cross-lingual corpus study. System 124:103396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103396

Pöchhacker F (2004) Introducing interpreting studies. Routledge, London/New York

Reppen R, Olson S (2020) Lexical bundles across disciplines. In: Römer U, Cortes V, Friginal E (eds) Academic writing: Effects of discipline, register, and writer expertise. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp 169–182

Reynolds BL, Wu W-H, Liu H-W et al. (2015) Towards a model of advanced learners’ vocabulary acquisition: an investigation of l2 vocabulary acquisition and retention by Taiwanese English majors. Appl Linguist Rev 6(1):121–144. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0006

Russo M (2011) Aptitude testing over the years. Interpreting 13(1):5–30. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.1.02rus

Schmitt N, Schmitt D (2014) A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in l2 vocabulary teaching. Lang Teach 47(4):484–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444812000018

Setton R, Dawrant A (2016) Conference interpreting: A trainer’s guide. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Sheng D (2024) A study on the compilation and publication of interpreting textbooks. Foreign Lang Res 237(3):63–68. https://doi.org/10.16263/j.cnki.23-1071/h.2024.03.001

Skoufaki S, Petrić B (2021) Academic vocabulary in an eap course: opportunities for incidental learning from printed teaching materials developed in-house. Engl Specif Purp 63:71–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2021.03.002

Song X (2016) A corpus-based study on vocabulary in textbooks for English majors. Educ Rev 206(8):123–126+130

Stamatović MV (2020) Vocabulary complexity and reading and listening comprehension of various physics genres. Corpus Linguist Linguist Theory 16(3):487–514. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2019-0022

Sun Y, Dang TNY (2020) Vocabulary in high-school EFL textbooks: texts and learner knowledge. System (93). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102279

Szudarski P (2018) Corpus linguistics for vocabulary: a guide for research. Routledge, New York

Tomlinson B (2012) Materials development for language learning and teaching. Lang Teach 45(2):143–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

Wang T, Xu Y (2013) The distribution of word families in college English textbooks. Technol Enhanc Foreign Lang Educ 153(5):10–15

Waring R, Nation P (2004) Second language reading and incidental vocabulary learning. Angl Engl Speak World 4:97–110

Webb S (2007) The effects of repetition on vocabulary knowledge. Appl Linguist 28(1):46–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/aml048

Webb S (ed) (2020) The routledge handbook of vocabulary studies. Routledge, London/New York

West M (1953) A general service list of English words. Longman, London

Yang L, Coxhead A (2020) A corpus-based study of vocabulary in the new concept English textbook series. Relc J 53(3):597–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220964162

Yao B (2017) An ideal scenario for compiling interpreting teaching materials. Shanghai J Transl 137(6):74–78

Zhao X, Liu X, Starkey H (2023) Ideological and political education in Chinese universities: structures and practices. Asia Pac J Educ 43(2):586–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1960484

Zhu Q, Xu J (2014) Presentation and treatment of vocabulary and grammar in well-received English textbooks published in foreign countries. Foreign Lang Learn Theory Pract 148(4):25–33+93

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No.: 22BYY044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dandan Sheng wrote the main paper text, and Xin Li helped analyze the data. Both authors reviewed and proofread the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The study does not involve human participants or their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheng, D., Li, X. A corpus-based assessment of vocabulary in interpreting textbooks. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05152-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05152-9