Abstract

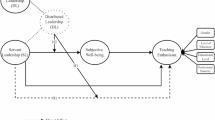

Servant leadership practices have been shown to enhance job satisfaction and organizational commitment; however, further research is still needed within the context of Omani educational institutions, particularly concerning female school leaders. This quantitative study seeks to deepen the understanding of servant leadership practices, especially regarding the leadership dynamics of female leaders in basic education schools. It aims to develop leadership performance and improve educational decision-making practices by investigating the status of servant leadership practices among female school leaders in basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman. Using the convenience sampling method, a questionnaire was administered to 178 female teachers to assess their views on the servant leadership practices of their school principals. The questionnaire consisted of two sections: demographic variables and servant leadership practices, which comprised five dimensions: empowerment, humility, and emotional recovery, assisting subordinates and providing organizational support, supervision and community building, and ethical conduct. Pearson correlation coefficients fell within acceptable limits, and Cronbach’s alpha indicated good reliability. SPSS was used to compute means, standard deviations, independent sample t-tests, and one-way ANOVA analyses. The study results showed that the level of servant leadership practices among female school leaders was generally moderate. Additionally, the results indicated no statistically significant differences in the participants’ responses attributable to the study variables. The findings can help specialized training centers develop tailored programs that address gender-specific leadership barriers and promote general leadership practices. Furthermore, the study results can guide policy reform efforts to support female leadership, emphasizing the integration of servant leadership practices within the educational framework to foster a supportive school environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid social and technological advancements have revolutionized the field of education. To keep pace with these developments, educational administrators must adopt leadership styles that enable effective management and continuous improvement. Servant leadership, first introduced by Robert Greenleaf in the 1970s, emphasizes leaders’ service to their followers, which has proven to be effective in enhancing teacher motivation and overall school performance (Greenleaf, 1977; see also Al-Azzam, 2023; Al-Hassoun, 2023). Servant leadership has become one of the most important leadership styles in the educational sector, particularly in Oman, where it has been used to address the unique cultural and societal challenges faced by female leaders. This leadership approach focuses on the needs of subordinates and the promotion of a supportive and collaborative environment that enhances job satisfaction, productivity, and organizational commitment (Abu Roman, 2021; Al-Bishr, 2023).

Recent studies have emphasized the effectiveness of servant leadership in creating a positive educational environment and achieving educational goals (Leithwood and Riehl, 2003, 3; Al-Badani, 2013). These studies recommend the development of clear strategies for implementing servant leadership and the creation of training programs to support its adoption in educational institutions (Al-Ajrafi, 2023; Al-Azzam, 2023; Al-Hassoun, 2023). By adopting a servant leadership approach, educational leaders can foster a culture of trust, loyalty, and satisfaction, eventually leading to better outcomes for both teachers and students.

Problem statement

While there has been extensive research on servant leadership in corporate settings, the practice is still underexplored in the context of educational institutions (Lemoine and Blum, 2019). Similarly, much research has been conducted on gender in leadership in Western contexts, but research on gender and leadership in other contexts, such as the Arab context, is considered scarce (Northouse, 2019). Moreover, studies have shown that female leaders can encounter difficulties in leadership more than men, which can negatively impact their effectiveness and increase the likelihood of adopting servant leadership practices (Scicluna Lehrke and Sowden, 2017). It is essential to point out this gender gap because servant leadership has been shown to have positive outcomes, such as increasing job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee engagement (Canavesi and Minelli, 2021). Adawi (2022) has recommended reinforcing a culture of servant leadership among female school leaders. Additional studies in Arab contexts have suggested that more research into women’s educational leadership is needed (Al-Lassasmeh, 2022; Awdah et al., 2022; Maasher and Al-Sharifi, 2017).

While a supportive work environment is relatively common in educational settings, servant leadership is particularly suitable because qualitative research suggests that it fosters a more inclusive and nurturing work environment (Wiramuda, 2017). Research shows that female leaders can work more effectively through servant leadership, yet female leaders do not fully benefit from this strength in educational institutions (Biddle, 2020). Consequently, exploring how female school leaders implement servant leadership can shed light on solutions to overcome gender-based challenges and improve leadership practices in schools.

Developing the educational system and improving its outcomes are essential to Oman Vision 2040, which prioritizes the preparation of educational leaders capable of achieving these goals. However, in the Omani context, previous studies have indicated some shortcomings that could negatively affect school leaders’ performance as servant leaders (Al-Rasbi, 2011). In a preliminary study conducted by the researcher, a sample of 10 female leaders from the Ministry of Education’s general administration and affiliated departments was asked, “Are you familiar with the concept of servant leadership?” The responses revealed confusion regarding the concept and its practices among the female leaders.

Based on the above, there is a lack of clarity regarding the concept of servant leadership and a shortage in its application by female leaders. This gap necessitates more research on the subject in order to introduce leaders to its importance and investigate how to implement it as a successful leadership style. Therefore, this study explores the servant leadership practices of female educational leaders in basic education schools in Oman.

Research questions

-

1.

What is the status of servant leadership practices among female school leaders in basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman?

-

2.

Are there statistically significant differences in servant leadership practices among female school leaders in basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman attributable to the variables of years of experience, academic qualifications, and specialization?

Aim of the study

To date, there has been no research in Oman focusing on female servant leadership in schools. Given the importance of this field and to address this gap, a questionnaire was developed to identify and evaluate the servant leadership practices of female school leaders from the perspectives of teachers. Previous discussions in the literature have emphasized how such data may be crucial for better educational reforms. Consequently, the central aim of the study is to identify the status of servant leadership practices among female school leaders in basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman and, through an analysis of the data, promote female servant leadership practices to foster more supportive school environments. Although this research is restricted to Oman, its results may be of significant value to female school leaders across Arab countries and beyond.

Significance of the study

This study seeks to enrich the theoretical literature by exploring the servant leadership practices of female school leaders in basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman, as research is scarce in this area. It aims to make a scientific contribution to Omani educational literature by revealing the reality of these practices, complementing previous studies that have researched servant leadership in general. Additionally, the study aligns with global trends calling for more research on servant leadership in different contexts. This study is consistent with Oman Vision 2040, which emphasizes the development of educational leaders capable of fulfilling their roles and improving the educational system. The results of this study are expected to benefit ministry training departments by informing training courses and workshops on key practices of servant leadership, which can help school leaders build a supportive work environment and, in turn, increase job satisfaction for teachers. Additionally, the findings are anticipated to benefit female leaders in the Ministry of Education by providing them with best practices for servant leadership, which they can utilize to achieve their goals. Furthermore, the study may inspire further research to explore other variables and factors not covered by this research or using different research methods on servant leadership, such as a qualitative methodology.

Definitions of terms

Servant leadership

According to Greenleaf (1977, p. 13), a servant leader can be defined as follows:

The servant-leader is servant first….It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or to acquire material possessions… The difference manifests itself in the care taken by the servant-first to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served.

In this study, servant leadership is defined as the overall score obtained by the sample members through the servant leadership questionnaire, covering dimensions of empowerment, humility, emotional healing, helping subordinates, organizational stewardship, supervision, community building, and ethical behavior.

Female leadership

Eagly and Carli (2003, p. 807) describe female leadership as “women occupying leadership roles in organizations, communities, or governments, where they influence decisions, drive progress, and inspire others. This concept highlights the importance of gender diversity in leadership, promoting equitable opportunities and representation for women across all sectors.” In this study, female school leaders are defined as women who hold the position of school principal or assistant principal in basic education schools in Oman during the 2023/2024 academic year.

Study limitations

The study focuses on servant leadership, exploring key dimensions such as empowerment, humility, emotional healing, helping subordinates, organizational stewardship, supervision, community building, and ethical behavior. It was conducted on a sample of teachers to gather their perspectives on the practices of female school leaders in basic education schools, which are affiliated with the Ministry of Education. The study’s convenience sample may limit the representativeness of the study population, as the number of respondents was only 178 out of an approximate total number of 16,505 female teachers in the Sultanate of Oman. The research took place during the 2024 academic year and was centered on basic education schools in Oman. Some factors that might affect the study results include school location and size, and leadership experience, which are not factored in this study. Experienced leaders could be assessed more positively by their teachers than those who are less experienced. Additionally, the school location and school size could impact the relationships between teachers and school leaders.

Theoretical framework

Servant leadership

Robert Greenleaf coined the term servant leadership in 1970. The intent was to place followers at the center of a leader’s attention, focusing on the human aspects of management. Greenleaf explained that servant leadership is based on developing individuals and their behaviors within an organizational framework that strives for better performance. He wanted to highlight leadership as an expression of the desire to serve others, as the leader serves his followers first, helping them reach their highest potential and demonstrating concern for them by providing appropriate support (Greenleaf, 1977). Greenleaf explained servant leadership as a method for serving others, sharing power, and supporting the work team. He added that servant leadership represents ethical principles and places the needs of subordinates at the core of the leader’s priorities, while creating a climate of importance, empowerment, and commitment. In addition, Greenleaf stated that servant leadership entails communication on a one-to-one basis, enabling the leader to understand the needs, abilities, desires, and goals of subordinates (Chiniara and Bentein, 2017). The explanations of servant leadership given by Greenleaf guided the development of the study instrument’s dimensions, such as empowerment, supervision and community building, and acting ethically.

When a leader becomes a servant leader, they rely less on institutional power and control, shifting authority to those being led. Servant leadership values the community because it provides a direct opportunity to experience interdependence, respect, trust, and individual growth (Greenleaf, 1977). Servant leadership represents a model that differs from other types of leadership. This type of leadership can be considered a philosophical style that interprets leadership through an ethical logic focused on the common good rather than personal gain. Servant leaders are dedicated to serving others with humility and integrity as a core belief, which makes their followers feel connected to them and puts them at the same level as any other individual in the group. The servant leader’s followers are the ones who set the stage from which to lead, based on their belief in the leader’s abilities (Spears, 2010). Servant leadership creates a cohesive climate among followers within an organization, which helps achieve familiarity and unity among them (Searle and Barbuto, 2010). Under this type of leadership, followers are more prosperous and wiser and have greater freedom and independence in performing their tasks (Greenleaf, 1977). Servant leadership is often popular because it is responsive to the environment and helps develop positive attitudes among followers (Sendjaya et al., 2008).

Impacts of servant leadership

Research results have shown that servant leadership has a positive impact on subordinates (Kool and Van Dierendonck, 2012). A recent study demonstrated that servant leadership can outperform other leadership styles in any organization and under any leader (Quenga, 2022). Heler and Marten (2018) emphasized the importance of utilizing servant leadership in educational institutions as it encourages leaders to seize opportunities to empower employees, thereby achieving the institution’s goals. Simultaneously, it promotes balance and stability among employees, which positively reflects on their performance.

Based on the increased awareness of the importance of servant leadership and its positive effects on several variables, such as individual performance, organizational behavior, achievement motivation, and decision-making participation, many studies have advocated for the application of servant leadership principles in the workplace. This research includes global studies such as Irfan et al. (2022), as well as Arabic studies such as Sabir and Al Khamas (2022), Abu Al-Maaty and Mansour (2022), and Al-Fahdi (2021). Other studies indicate that one of the key aspects of servant leadership is its focus on building strong relationships and promoting teamwork (Chen et al., 2021; Van Dierendonck et al., 2014). For many, servant leadership is currently considered one of the most important leadership styles in educational institutions, as it focuses on developing employees and continuously improving their performance (Giambatista et al., 2020).

Female servant leadership

Several studies have addressed the topic of servant leadership from various angles, including the effectiveness of leadership between men and women. A study conducted by Bailey (2014) found that women outperformed men in leadership effectiveness in fields employing larger numbers of women, such as education and social services. Women are expected to foster greater collaboration and support social values that promote the welfare of others (Eagly and Karau, 2002), thus practicing and encouraging the use of servant leadership.

Additionally, studies have identified differences between the leadership styles of women and men. Research indicates that men rate themselves more positively than women and use a more strategic, empowering style, while women employ a more forceful executive style (Kaiser and Wallace, 2016; Kruger, 2008; Book, 2000). Another study highlighted that women’s leadership style is not necessarily less effective than men’s; in fact, they are more effective in organizations that rely on teamwork. The same study also noted that the perception that women’s leadership style is less effective than men’s is not based on facts but rather driven by social conditioning or social construction (Lee, 2023; Appelbaum et al., 2003). Moreover, women were found to be more effective than men in employing servant leadership, especially in fields such as healthcare and education (Lemoine and Blum, 2019). Northouse (2019) reported that women were more likely to focus on the welfare of others and ethical behavior. Women also tend to inspire their followers more and go above and beyond to serve them, leading to higher satisfaction with women’s leadership compared to male leaders. These findings indicate that the leadership style that women may prefer is servant leadership, which emphasizes the welfare and service to subordinates. A study by Eagly and Karau (2002) suggested that servant leadership is an ideal leadership style for women.

In general, women are more likely to exhibit behaviors and values associated with servant leadership. They tend to choose jobs based on the presence of supportive cultures and supervisors (Tobias and Kirby, 2022), and they seek employees with good communication skills (Wiese et al., 2022). All of these factors are naturally part of servant leadership, as indicated by Andrade’s (2023) study, which showed that one of the advantages of this style is that it encourages growth and advancement within organizations, especially for women. Overall, Greenleaf’s servant leadership theory encourages women to serve and build community, while enhancing their educational role in school leadership, which aligns with the goals of the Ministry of Education in the Sultanate of Oman.

Methodology

General background

This study employed a quantitative methodology, using a questionnaire to explore female servant leadership practices in basic education. The study was conducted between April 25 and May 5, 2024. The research received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at Sultan Qaboos University. It was also granted approval from the Department of Educational Studies and International Cooperation in the Ministry of Education in Oman, affirming its adherence to high ethical standards. The approval encompasses all data collection procedures involving human participants as outlined in the study’s methodology. All research activities were conducted in strict compliance with relevant institutional and national ethical guidelines, adhering to the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. These guidelines ensure that the study upholds the highest ethical standards applicable to research involving human subjects. Participants’ involvement was voluntary, with assurances provided that their participation would not affect their professional roles. It was explicitly communicated that the aim of data collection was completely for research purposes. To protect confidentiality and adhere to ethical guidelines, all data were pseudonymized. This method allowed data to be connected for analysis, but it prevented any information from being traced back to specific teachers, thereby ensuring complete anonymity.

In our study, we rigorously ensured that informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to participation. This procedure was conducted in accordance with ethical standards that prioritize respect for participant autonomy and informed decision-making. Participants were thoroughly briefed on the study’s goals, methods, potential effects, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. In instances where consent was deemed unnecessary, a comprehensive justification was provided based on specific exemptions acknowledged by the Research Ethics Committee, ensuring that such decisions adhered to ethical guidelines and did not compromise participant welfare or rights.

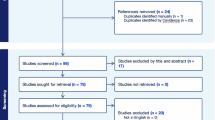

Sample selection

The study’s sample consisted of 178 Omani female teachers working all around Oman. The participants volunteered to fill out the survey and participate in the study. They were selected using a convenient sampling method, ensuring a representative mix of different demographics such as academic qualifications, years of experience, and specialization. According to Kadilar and Cingi (2005), this approach effectively merges random selection with categorization, supporting both quantitative and qualitative research methods. The researchers chose convenience sampling as it has practical benefits, including a low cost and fast data collection (Turner, 2020). The sample was chosen to ensure that the participants had access to the survey instrument, and they were ready to participate. Table 1 details the survey participants according to years of experience and qualifications.

Instrument and data collection

To achieve the research objectives, the current study relied on the Servant Leadership Questionnaire. This survey was developed based on previous studies and validated scales, such as the Servant Leadership Scale by Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011) and Barbuto and Wheeler (2006). While adapting the study instrument, the Omani educational context, cultural differences, and the dominant use of the Arabic language were considered. Next, the instrument was reviewed by experts in the educational field, who evaluated the accuracy and relevance of each item within prescribed dimensions. According to the feedback given from experts, some changes were made, such as deleting some items because they were repeated in two dimensions of the tool. The revised questionnaire consisted of 27 items distributed across five dimensions: empowerment, humility and emotional healing, assisting subordinates and organizational care, supervision and community building, and ethical behavior. The questions utilized a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). Table 2 presents the study instrument and its dimensions. After the tool was assessed by experts, a psychometric analysis was done to judge its performance. The next step was data gathering, which involved administering the new instrument. The study instrument was distributed using Google Forms via an online link. It was sent to female teachers in cycle-one basic education schools all around Oman.

Analysis techniques

The validity of the study instrument was tested by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between each dimension and the phrases belonging to it. The phrase correlation coefficients ranged from 0.911 to 0.967, as shown in Table 3 (see Appendix), and they were all statistically significant at a significance level of 0.01, which confirms that the scale has appropriate validity indications to achieve the objectives of the current study.

To test the reliability of the study instruments, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each dimension and for the entire instrument. Table 4 (see Appendix) shows that the stability coefficients in the responses were high, as the stability coefficient for the tool reached 0.993. We found that the stability coefficient is very high, which confirms that the tool is characterized by a high degree of stability and confirms reliability and internal consistency of the study sample responses.

The study instrument was distributed to a sample of the study population (16,505 teachers) through an electronic link sent to the targeted participants. The data collection process resulted in 178 complete responses. The study data were analyzed using SPSS, applying various statistical techniques, such as Pearson’s correlation and descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations. Additionally, T-tests and a one-way ANOVA were used due to their suitability to the study variables.

To classify the responses of the study sample, the criterion set by Sekaran and Bougie (2016) was used for evaluating the means of each item. Subsequently, the responses of the study sample were classified into three categories as shown in Table 5.

Results

Results of the first research question

To address the first research question (What is the status of servant leadership practices among female school leaders in basic education schools in Oman?), the means and standard deviations were calculated for each dimension of servant leadership. The results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6 shows that the responses of the study sample indicated a moderate level of servant leadership practices, with an overall mean of 3.9241. All the dimensions were rated as moderate, with the ethical behavior dimension having the highest mean score (3.9841), followed by supervision and community building (3.9472). The humility and emotional healing dimension came next with a mean of 3.9129, while assisting subordinates and organizational care had a slightly lower mean (3.8899), and empowerment had the lowest mean score (3.8865). These results suggest that servant leadership practices are present at a moderate level among school leaders. The results of each dimension are shown in Tables 7–11 at the end of this manuscript.

Results of the second question

For the second research question (Are there statistically significant differences in the practices of female school leaders in servant leadership at cycle-one basic education schools in Oman attributed to the variables of academic qualification, years of experience, and specialization?), an independent-samples t-test was used to determine the differences according to the variable of academic qualification, and a one-way ANOVA was used to determine the differences based on the variables of years of experience and specialization.

Differences according to the variable of academic qualification

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to examine the differences between the mean ratings of the study sample regarding the degree of practice of female leaders in servant leadership at basic education schools in Oman that are attributed to the variable of academic qualification. Table 12 presents the results.

It is evident from Table 12 that there are no statistically significant differences in the degree of practice of female leaders in servant leadership at cycle-one basic education schools in Oman attributed to the variable of academic qualification. Next, one-way ANOVAs for the study sample’s estimates based on years of experience and specialization were conducted (Tables 13 and 14).

It is evident from Table 13 that there are no statistically significant differences at the significance level (α = 0.05) between the estimates of the study sample regarding the practice of female leaders in servant leadership based on years of experience.

As shown in Table 14, there are no statistically significant differences at the significance level (α = 0.05) between the study sample’s estimates of female school leaders’ servant leadership practices based on specialization.

Discussion

Discussion related to the first research question

The results of the study indicate that female school leaders practice servant leadership with their teachers at a moderate level. This moderate level of servant leadership is not considered a negative outcome; however, it indicates that servant leadership practices have not yet reached the desired level. This result may suggest that the study sample recognizes differences in how school principals practice servant leadership, depending on their personalities, experiences, the responsibilities they bear, and, perhaps, the size of their schools. From the researchers’ point of view, this result may be due to the principals’ adherence to the laws and regulations issued by the Ministry of Education. Moreover, some school principals may practice servant leadership without knowing the specific term for this leadership style or its role in developing educational and administrative work, which could explain why the sample’s perceptions of the level of practice were moderate.

Servant leadership, as a leadership style in contemporary educational institutions, focuses on the development and empowerment of staff to enhance their performance. It encourages school principals to care for subordinates, apply principles of transparency and empowerment, and reduce work pressures on leadership by increasing the autonomy of subordinates to make decisions (Ibrahim and Al-Marzouqi, 2021). These results may also be attributed to the positive impacts of the Ministry of Education’s efforts, including leadership development programs, such as the School Leadership Program provided by the Specialized Institute for Teachers, which teaches school leadership models (Specialized Institute for Vocational Training for Teachers, 2023). Additionally, the Ministry of Education offers support for school leaders to pursue master’s and doctoral programs in educational administration, both within and outside Oman, contributing to the availability of moderate servant leadership practices. Furthermore, the Ministry has issued several decrees, publications, guides, and regulations that support servant leadership practices, such as the School Performance Development System Guide, the School Administration Work Guide, the School Councils and Committees Guide, the Guide to School Job Functions and Approved Positions, and the Parent Council Regulations (Ministry of Education, 2016).

The survey results are consistent with the findings of Al-Mahdi et al. (2016), which also determined that servant leadership dimensions were moderately present among school principals from the perspective of their teachers. The findings also align with Al-Thawab (2022), which found that the practices of servant leadership among school principals were moderately present. However, the current study’s findings differ from those of Al-Shuaili (2024) and Ibrahim and Al-Shuhoumi (2018), who reported high levels of servant leadership practices.

Table 7 shows that the empowerment dimension was perceived as having a moderate level of practice, with a mean score of 3.89, which is the joint lowest among the study’s dimensions. This result can be interpreted as indicating that school leaders still have some shortcomings regarding empowerment. It reflects a lack of focus by female school leaders on empowering teachers, possibly due to their concentration on completing all assigned administrative tasks, which consume their time, leaving insufficient room for teacher empowerment. Additionally, this result may be attributed to the leaders’ lack of understanding of the importance of empowerment in the school environment. Empowering teachers allows them to assume many roles typically managed by the school administration, thus reducing the administrative burden. This outcome may also be due to the weak directives issued by the Ministry of Education concerning teacher empowerment in schools.

Within the empowerment dimension, the statement “encourages me to use my abilities at work” received the highest mean score of 3.97. This result indicates that school leaders are keen to motivate employees to display their full potential at work, which enhances their ability to achieve their professional goals. This finding aligns with Antonakis et al.’s (2012) view about the role of servant leadership. On the other hand, the statement “gives me the authority to make decisions that facilitate my work” received the lowest mean score of 3.80. This result can be explained by the lack of sufficient authority among school leaders to grant teachers decision-making powers, which is likely due to the administrative system that defines decision-making authority in schools, where these powers are often concentrated in the hands of the school principal or assistant principal, reducing opportunities to delegate authority to teachers. For example, in 2015, the Ministry of Education issued the School Job Duties and Tasks Manual, which outlined the duties and responsibilities of principals and constrained the decision-making process, limiting the effectiveness of educational leadership in some cases (Ministry of Education, 2015).

Table 8 indicates that perceptions of the humility and emotional healing dimension were moderate, with a mean score of 3.91. The first researcher, who has more than 15 years of experience as a teacher in basic education schools, attributes this moderate result to the cumulative experience of school leaders, including school principals and assistant principals, who strive to commend teachers’ achievements and provide a supportive environment for success. These leaders also demonstrate humility when interacting with teachers, setting an example of leadership that prioritizes the school’s interests over personal ones. Humility is an ethical trait and behavioral practice that enhances respect and appreciation for the leader, giving those who practice this management style a distinctive outlook that prioritizes support for staff in all matters, including problem-solving and organizational care. All of these traits are characteristic of the servant leadership models described in prior literature (Greenleaf, 1977; Spears, 2010).

Within the humility and emotional healing dimension, the statement, “praises the achievements of his employees,” received the highest mean score (4.05), while the statement, “considers himself part of the team,” received a mean score of 4.01, indicating a high level of practice. These results suggest that school leaders understand the importance of building trust and motivation among teachers and are committed to providing continuous support and acknowledging their creativity. School leaders who work alongside teachers as part of a collaborative team demonstrate some of the key traits of servant leadership discussed by Spears (1998)—dedication, humility, and integrity in providing support and services to employees—contributing to the creation of an inspiring and impactful educational environment. According to Pramitha (2020), female leaders in educational institutions must possess strong leadership skills and the ability to innovate and create, which aligns with the findings of the study regarding the importance of the leader praising employees’ achievements and working as part of a collaborative team. The findings also suggest that leaders are responsible for their institutions and work to motivate their teams to foster an effective educational environment.

Table 9 shows that perceptions of the helping subordinates and organizational stewardship dimension were moderate, with a mean score of 3.89. Only one statement in this dimension was perceived at a high level. Statement 13, “follows up on the general goals and tasks required from all staff,” received the highest mean score (4.02), indicating a high level of practice, while four statements were rated as moderate. Participants in the study perceived that female school leaders continuously follow up to ensure the achievement of intended goals, demonstrate commitment to teachers’ professional development, and help them improve their skills and capabilities in alignment with their goals. These responsibilities are outlined in the Guide for School Job Functions and Approved Positions issued by the Ministry of Education (2015). Servant leadership focuses on the institution’s general welfare, developing subordinates, and fostering teamwork and collaboration. Attending to subordinates and caring for them involves nurturing their development and improving their skills and capacities, which aims to boost their self-confidence and give them a sense of personal empowerment, encouraging their personal growth (Laub, 1999; Spears, 2010).

Table 10 reveals that the supervision and community building dimension received a moderate level of practice, with a mean score of 3.95, and all statements in this dimension were rated as moderate. This result may indicate some challenges among female school leaders in fulfilling their community responsibilities and community-building roles. A possible reason for this result is the overwhelming number of tasks assigned to the school principal—42 according to the guide issued by the Ministry of Education (2015). School principals may not have enough time to communicate effectively with teachers and the local community or to encourage them to engage in volunteer work for the community. Franco and Antune (2020) identified community building as one of the seven variables of servant leadership. However, the Guide for School Job Functions does not specify any tasks directly related to supervision and community building. Given this result, the Ministry of Education should encourage more volunteer initiatives for community service while fostering effective communication with the local community to prepare servant leaders capable of achieving higher levels of the practices embodied in servant leadership. The importance of this leadership style is evident through the positive outcomes it achieves at various levels, including community development, as it focuses on the human virtues that contemporary societies need.

Table 11 shows that the ethical behavior dimension received a moderate level of practice, with a mean score of 3.98. Liden’s (2015) multidimensional model of servant leadership identifies ethical behavior as a distinct dimension, meaning interacting with subordinates with honesty, fairness, and complete integrity. Ethics are a cornerstone of any educational system, and the appointment of a principal is rooted in ethical standards that include good conduct and adherence to the ethics of the teaching profession. The survey result reflects the servant leaders’ commitment to ethical conduct, which elevates the institution and helps achieve its goals, completing tasks efficiently and positively impacting individuals. It shows that servant leaders take responsibility for their work, care about professional ethics, and commit to effectively using their time. The results also show that the statement, “takes responsibility at work,” received the highest mean score (4.10). This result reflects the attention female school leaders pay to completing school tasks thoroughly while adhering to ethical behavior, as they bear the responsibility of instilling ethics in teachers as an antecedent to achieving educational goals. However, the moderate rating for this dimension could also be a reflection of the overwhelming administrative tasks and pressures that school principals face. Additionally, personal and professional factors may lead some school principals to favor or be more inclined towards certain teachers over others, based on personal relationships rather than professional competence, resulting in a relative deficiency in acting ethically and satisfactorily (Table 11).

Discussion related to the second research question

The results related to the second question indicate that there was agreement among the teachers, regardless of their academic qualifications, on the extent to which female school leaders practice servant leadership. Firstly, academic qualifications do not have an impact on the perception of servant leadership practices. This result can be explained by the fact that all the teachers in the study sample undergo various professional development programs, both inside and outside the school, that address their different professional needs. Additionally, the Ministry of Education provides a variety of scientific publications, such as booklets, guides, and scientific journals, which help teachers enhance their professional development. This finding is consistent with the studies of Ibrahim and Al-Shuhoumi (2018) and Al-Shuaili (2024), which found no statistically significant differences in their study sample estimates attributable to the academic qualification variable (Table 12).

The results also showed that teachers held similar views regardless of years of experience (Table 13). The teachers in the survey work in a similar school environment governed by the same regulations, legislation, and ministerial decisions, and they receive the same level of professional support from educational supervisors. Moreover, female school leaders participate in the same professional development workshops and courses, aimed at enhancing leadership skills, regardless of differences in years of experience. All teachers perform the roles and tasks assigned to them as required, irrespective of experience level, which explains why this variable does not show significant differences in the results. These results align with the findings of Ibrahim and Al-Shuhoumi (2018) and Al-Shuaili (2024), who also found no statistically significant differences based on years of experience.

The current study further revealed that participants from all specializations agreed about how much school leaders possess the qualities and characteristics of empowerment, ethical behavior, humility, emotional healing, supervision, community building, supporting subordinates, and organizational stewardship. This indicates that specialization does not affect the participants’ estimates of the extent to which school leaders practice servant leadership (Table 14).

Conclusion and implications for female leadership

The results of this study on servant leadership practices among female leaders in basic education schools in Oman indicate a need to activate a range of practical applications to enhance the practice of this leadership style, which research has shown can improve the educational environment. At the local level, the outcomes can be translated into training and professional development programs based on servant leadership concepts that target female leaders. Such programs should focus on empowering female teachers, motivating work teams, and enhancing organizational culture. Additionally, servant leadership indicators should be included in leadership performance evaluation standards and linked to administrative empowerment plans. At the regional level, experience exchanges through workshops and educational conferences among female leaders in Oman and throughout the Gulf countries that highlight best practices and educational applications in servant leadership should be prioritized and facilitated. These outcomes also present an opportunity to enhance the presence of female leadership in the educational field at the global level by contributing to the development of more just and humane leadership models in the education sector worldwide.

Future directions

In line with the findings and outcomes of the study, future research should examine the impact of servant leadership among female leaders on teachers’ performance and professional motivation in basic education schools, as well as explore the role of servant leadership in promoting organizational culture and a collaborative work environment in schools.

Recommendations

-

Design professional training programs that enhance the understanding and skills of servant leadership among female school leaders, taking into account individual differences in qualifications, specialization, and years of experience.

-

Incorporate servant leadership practices into the performance evaluation criteria for school principals, linking them to professional development plans and administrative empowerment.

-

Review appointment and promotion policies for school leadership positions to ensure alignment with modern leadership competencies, especially those related to servant leadership practices.

Suggestions

We suggest that the Ministry of Education adopt creative initiatives to promote a culture of teacher empowerment through inspiring awareness campaigns that highlight the impact of empowerment on enhancing school performance and motivation in the workplace. We also recommend designing an innovative supervisory system that integrates professional support with psychological care, utilizing modern technologies and advanced counseling methods to foster psychological recovery for school staff. Furthermore, we call for activating innovative community partnerships with local associations and institutions to promote volunteerism and joint community initiatives, thereby contributing to a collaborative and positively engaged school ecosystem.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Materials availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Maryam Al-Muzahimi.

References

Abu Al-Maaty W, Mansour M (2022) Servant leadership and its relationship with the big five personality traits among public school principals in Dakahlia Governorate. J Fac Educ 38:463–523. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1275865

Abu Roman S (2021) The degree of practicing servant leadership among the principals of governmental secondary schools in Amman governorate and its relation to teachers’ motivation towards work. J Educ Psychol Sci 5(51):124–141. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1236933

Adawi F (2022) Leadership practices of female middle school leaders in Jazan in light of servant leadership. J Fac Educ Mansoura 118(3):948–989. http://search.mandumah.com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/1334035

Al-Ajrafi F (2023) A proposed vision for developing the performance of school leaders at the secondary level in light of the dimensions of servant leadership. Islam Univ J Educ Soc Sci 13:59–82. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1361472

Al-Azam MF (2023) The reality of servant leadership and its relationship with job satisfaction from the perspective of faculty members at the University of Hail J Educ Psychol Sci 7(16):1–19 https://search.mandumah.com/Record/1379245

Al-Badani MN (2013) Fundamentals of administration and educational supervision from both a general and Islamic perspective. University of Faith, Department of Purification and Education. https://www.noor-book.com/pdf

Al-Bishr SG (2023) Servant leadership among secondary school principals in Riyadh and its relationship with job satisfaction from the teachers’ perspectives Arab J Educ Psychol Sci 7(35):341–360 http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1412416

Al-Fahdi R (2021) The degree of practice of scientific thesis supervisors for servant leadership at Sultan Qaboos University and its relationship with the achievement motivation of the students. Al-Andal J Humanit Soc Sci 49(79):79–103. http://search.mandumah.com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/1195464

Al-Hassoun AM (2023) The degree of servant leadership dimensions practiced by female principals of public secondary schools in Buraidah from the teachers’ perspectives. Arab J Educ Psychol Sci 31:25–60. http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1348388

Al-Lassasmeh M (2022) The effect of servant leadership on improving the quality of work life: Organizational commitment as a mediating variable: an applied study in the Social Security Institution/Center. (Publication No. 1277419). Dar Al-Manzuma Database, theses. Master’s thesis, Mutah University. https://search-mandumah-com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/1277419

Al-Mahdi YF, Al-Harthi AS, Salah El-Din NS (2016) Perceptions of school principals’ servant leadership and their teachers’ job satisfaction in Oman. Leadersh Policy Sched 15(4):543–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2015.1047032

Al-Rasbi SH (2011) Dimensions of the prevailing organizational climate in post-basic education schools in the Sultanate of Oman from the teachers’ perspective. (Publication No. 962951). Dar Al-Mandumah Database, University Theses. Master’s Thesis, Sultan Qaboos University. https://search-mandumah-com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/962951

Al-Shuaili SS (2024) The level of availability of servant leadership dimensions among principals of schools in the Wilayat of Bahla in the Al-Dakhiliyah Governorate in Oman in light of the Olesia et al. model Arab Stud Educ Psychol 149:205–228. https://search.mandumah.com/Record/1442382

Al-Thawab SM (2022) The reality of applying servant leadership among secondary school principals in Al-Khafji Governorate from the teachers’ perspectives King Khalid Univ J Educ Sci 9(3):171–192. http://search.mandumah.com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/1315601

Andrade MS (2023) Servant leadership: developing others and addressing gender inequities. Strateg HR Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-06-2022-0032

Antonakis J, Day D, Schyns B (2012) Leadership and individual differences: at the cusp of a renaissance. Leadersh Q 23(4):643–650. https://2u.pw/Pfwt3QVI

Appelbaum SH, Audet L, Miller JC (2003) Gender and leadership? Leadership and gender? A journey through the landscape of theories. Leadersh Organ Dev J 24(1):43–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730310457320

Awdah W, Mishmish AM, Asayed AK (2022) The impact of servant leadership behavior on the quality of work life of employees of the Palestinian Ministry of Interior and National Security in the Gaza Strip. J Islam Univ Econ Adm Stud 30(3):33–55. http://search.mandumah.com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/1295831

Bailey S (2014) Who makes a better leader: a man or a woman? Forbes. https://2u.pw/gAADLrPI

Barbuto JE, Wheeler DW (2006) Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ Manag 31(3):300–326. https://2u.pw/BtrJHNhh

Biddle M (2020) Women have the advantage in servant leadership. UBNow: news and views for UB faculty and staff. Retrieved from https://www.buffalo.edu/ubnow/stories/2020/01/lemoine-servant-leadership.html

Book EW (2000) Why the best man for the job is a woman. HarperCollins, New York, NY. https://2u.pw/A0SbngPG

Canavesi A, Minelli E (2021) Servant leadership and employee engagement: a qualitative study. Springer. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10672-021-09389-9.pdf

Chen X, Wang J, Chen J, Chen H (2021) Servant leadership and team performance: the role of team cohesion. Front Psychol 12:670573, https://2u.pw/qzXJMRpg

Chiniara M, Bentein K (2017) The servant leadership advantage: when perceiving low differentiation in leader-member relationship quality influences team cohesion, team task performance and service OCB. Leadersh Q 29(2):333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.002

Dierendonck D, Nuijten I (2011) The servant leadership survey: development and validation of a multidimensional measure. J Bus Psychol 26(3):249–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

Van Dierendonck D, Stam D, Boersma P, De Windt N, Alkema J (2014) Same difference? Exploring the differential mechanisms linking servant leadership and transformational leadership to follower outcomes. Leadersh Q 25(3):544–562. https://2u.pw/7xRW1PsU

Eagly AH, Karau SJ (2002) Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev 109(3):573. https://2u.pw/gSvgyAnQ

Eagly AH, Carli LL (2003) The female leadership advantage: an evaluation of the evidence. Leadersh Q 14(6):807–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.004

Franco M, Antune A (2020) Understanding servant leadership dimensions: theoretical and empirical extensions in the Portuguese context. Nankai Bus Rev Int 11(3):345–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-08-2019-0038

Giambatista R, McKeage R, Brees J (2020) Cultures of servant leadership and their impact J Values Based Leadersh 13(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.22543/0733.131.1306

Greenleaf RK (1977) Servant leadership: a journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press. https://2u.pw/OYQcxJPP

Heler S, Martin J (2018) Servant leadership theory: opportunities for additional theoretical integration. J Manag Issues 1(1):230–243. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45176580

Ibrahim H, Al-Shahoumi S (2018) The degree of availability of servant leadership dimensions among basic education school principals in Al-Dhahirah Governorate in the Sultanate of Oman in light of the Laub Model. Int J Educ Psychol Stud 4(1):136–159. https://search.mandumah.com/Record/1251509

Ibrahim H, Al-Marzouqi A (2021) A proposed model for servant leadership in schools in the Sultanate of Oman in light of some contemporary models. Arab J Spec Educ 16:143–180. https://maqsurah.com/home/item_detail/73257

Irfan M, Salameh AA, Saleem H, Naveed RT, Dalain AF, Shahid RM (2022) Impact of servant leadership on organization excellence through employees’ competence: Exploring a cross-cultural perspective. Front Environ Sci 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.985436

Kadilar C, Cingi H (2005) A new estimator using two auxiliary variables. Appl Math Comput 162:901–908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2003.12.130

Kaiser RB, Wallace WT (2016) Gender bias and substantive differences in ratings of leadership behavior: toward a new narrative. Consult Psychol J Pract Res 68(1):72–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000059

Kool M, van Dierendonck D (2012) Servant leadership and commitment to change, the mediating role of justice and optimism. J Organ Change Manag 25(3):422–433. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811211228139

Kruger ML (2008) School leadership, sex and gender: welcome to difference. Int J Leadersh Educ 11(2):155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701576266

Laub JA (1999) Assessing the servant organization. Development of the servant organizational leadership (SOLA) instrument. https://2u.pw/mDzYQy0U

Lee C (2023) How do male and female headteachers evaluate their authenticity as school leaders? Manag Educ 37(1):46–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020621999675

Leithwood KA, Riehl C (2003) What we know about successful school leadership. National College for School Leadership, Nottingham, p 406028754–1581215021. https://2u.pw/NmnrgDL3

Lemoine GJ, Blum TC (2019) Servant leadership, leader gender, and team gender role: testing a female advantage in a cascading model of performance. Pers Psychol 74(1):3–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12379

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Meuser JD, Hu J, Wu J, Liao C (2015) Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh Q 26(2):254–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

Maasher FS, Al-Sharifi AA (2017) The level of practice of servant leadership by school principals of the General Secretariat of Christian Educational Institutions in Amman from the teachers’ perspective Mu’tah J Res Stud Humanit Soc Sci Ser 32(1):73–114 https://search-mandumah-com.squ.idm.oclc.org/Record/845018

Ministry of Education (2015) Guide to school job responsibilities and the approved workloads. Ministry of Education. https://lib.moe.gov.om/home/item_detail/49541

Ministry of Education (2016) The Specialized Center for Vocational Training for Teachers. 2016 Guide, Muscat. https://home.moe.gov.om/library/102

Northouse PG (2019) Leadership theory and practice, 8th edn. SAGE Publications. https://2u.pw/4LnP6ftw

Pramitha D (2020) Women in educational leadership from islamic perspectives. EGALITA J Kesetaraan dan Keadilan Gend 15(No 2):15–26. https://doi.org/10.18860/egalita.v15i2.10805

Quenga MD (2022) Leading Change: A Quantitative Analysis of Servant Leadership and Resistance to Change (Order No. 29321350). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2708719019). https://2u.pw/VOvPzMth

Sabir AN, Al-Khamas MA (2022) The influence relationship between servant leadership and workplace spiritual values: an applied study in some colleges of Basra University Econ Sci 17(65):159–187 http://search.mandumah.com/Record/1303794

Scicluna Lehrke L, Sowden R (2017) Servant leadership: a feminine touch. Sites at Penn State. Retrieved from https://sites.psu.edu/leadership/2022/11/06/servant-leadership-a-feminine-touch/

Searle TP, Barbuto JE (2010) Servant leadership, hope, and organizational virtuousness: a framework exploring positive micro and macro behaviors and performance impact. J Leadersh Organ Stud 18(1):107–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051810383863

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2016) Research methods for business: a skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons. https://2u.pw/dFBMaNWN

Sendjaya S, Sarros JC, Santora JC (2008) Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviors in organizations. J Manag Stud 45(2):404–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00761.x

Spears LC (2010) Character and servant leadership: ten characteristics of effective, caring leaders. J Virtues Leadersh 1(1):25–30. https://2u.pw/XPoaoKou

Spears LC (1998) Insights on leadership: Service, stewardship, spirit, and servant-leadership. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Toronto. https://commons.emich.edu/mgmt_facsch/81/

Specialized Institute for Vocational Training for Teachers (2023) The program for school directors and their assistants (School Leadership). https://2u.pw/MeSgG

Tobias J, Kirby F (2022) “Female managers’ progression to first-line management in male dominated environments?” In: Paper presented at the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, WA, United States, 5–9 August. https://2u.pw/4vns7WRY

Turner DP (2020) Sampling methods in research design. Headache J Head Face Pain 60(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13707

Wiese MT, Conen K, Alewell D (2022) “Gender-differences in affective motivation to lead. The roles of risks propensity & self-stereotyping.” In: Paper presented at the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, WA, United States, 5–9 August. https://2u.pw/ANKgsNmR

Wiramuda P (2017) The meaning of servant leadership: a qualitative phenomenological study. IJASOS Int E J Adv Soc Sci 3(9):859–872. https://2u.pw/k853m

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this article was financially supported by Sultan Qaboos University (Ref No. REAAF/EDU/DEFA/2024/05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The main author is Maryam Al-Muzahimi. This manuscript is a part of a PhD study. Maryam developed the idea, wrote the initial draft, collected the data, and analyzed it. Fathi supervised the study, reviewed the draft, edited it, and wrote the recommendations and suggestions. Houda conducted the review and reanalyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee in Sultan Qaboos University (Ref No. REAAF/EDU/DEFA/2024/05) on April 17, 2024. It has also been granted approval from the Department of Educational Studies and International Cooperation in the Ministry of Education in Oman (Approval Number: 2824161852). The approval encompasses all data collection procedures involving human participants as outlined in the study’s methodology. All research activities were conducted in strict compliance with relevant institutional and national ethical guidelines, adhering to the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. These guidelines ensure that the study upholds the highest ethical standards applicable to research involving human subjects.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating preservice teachers before the study commenced. This consent covered participation, data collection, and the publication of research findings. The consent process, conducted by the first author from April 25 and May 5, 2024, included detailed explanations regarding the study’s purpose, data use, and confidentiality measures, with assurances of anonymity for all participants. No minors were involved in this study.

Disclosure of the use of artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence tools were used in this research solely to assist with translation and minor linguistic modifications, with all texts being manually reviewed to ensure scientific accuracy.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Muzahimi, M.K.R.M., Abunaser, F.M. & Al-Housni, H.A.M. Exploring female leadership: servant leadership practices in basic education in Oman. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1078 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05185-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05185-0