Abstract

This study examines the impact of common institutional ownership on corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A) within China’s emerging market. The findings suggest that, while common institutional ownership decreases the likelihood of M&A, it positively influences the merger announcement effect and merger performance. The heterogeneity analysis reveals that long-term and independent institutional investors play a more significant role in facilitating effective M&A. The mechanism analysis identifies two primary channels through which common institutional ownership exerts its influence: first, by leveraging acquisition experience and informational advantages to mitigate information asymmetry; second, by appointing directors and curbing managerial opportunism to strengthen corporate governance. These findings provide novel empirical evidence regarding the dual role of common institutional ownership in M&A, enriching the literature on its economic impact in emerging markets. Furthermore, they offer valuable insights for advancing well-structured M&A practices and refining capital market regulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) play a fundamental role in corporate growth and capital allocation within an economy. However, contrary to traditional M&A theories, which posit that mergers enhance firm value (Jensen and Ruback, 1983), a substantial body of research suggests that many acquisitions fail to create value and may even result in value destruction (Moeller et al., 2004; Bhaumik and Selarka, 2012; Zhu et al., 2024). This issue is particularly pronounced in emerging markets, which are often characterized by underdeveloped capital market institutions and persistent corporate governance challenges. Data indicate that, as of 2020, 51.2% of M&A transactions in China’s capital market failed to generate value and, in some cases, even resulted in firm value erosion (Zhu et al., 2024).

As key stakeholders, why do common institutional investors fail to prevent value-destructive mergers? This question has attracted significant academic attention. Matvos and Ostrovsky (2008) examined this issue from the perspective of common institutional ownership, contending that these investors may offset losses from unsuccessful mergers through higher returns from non-acquiring firms. However, Brooks et al. (2018) present empirical evidence that challenges this argument. Considering the multifaceted role of common institutional ownership in M&A, its effectiveness as a governance mechanism, as opposed to its passive acceptance of value-destructive mergers, remains an unresolved issue that requires further empirical investigation.

In practice, common institutional ownership has become an increasingly prevalent ownership structure.Footnote 1 The academic debate on its influence on corporate decision-making revolves around two contrasting perspectives: the effective governance view, which argues that common institutional ownership enhances corporate oversight (He and Huang, 2017), and the collusion hypothesis, which suggests that it undermines governance by fostering anti-competitive behavior (Azar et al., 2018). On one hand, common institutional investors serve as crucial information intermediaries within complex corporate networks, thereby enhancing communication and knowledge dissemination (Edmans et al., 2019; Hope et al., 2017). On the other hand, they may engage in collusive behavior with peer firms, manipulating market dynamics to secure reciprocal advantages (Azar et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2024). While their primary objective is to maximize portfolio value, institutional constraints in emerging markets—such as underdeveloped market institutions and concentrated ownership structures—limit their capacity for active governance (“voting with their hands”) and reduce their incentive to divest from underperforming firms (“voting with their feet”). This raises a critical question: In the context of major corporate decisions, such as M&A, can common institutional ownership serve as an effective governance mechanism?

In contrast to the studies by Zhu et al. (2024) and Brooks et al. (2018), which focus exclusively on unsuccessful acquisitions or acquisition premiums, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of the M&A process, covering pre-deal decision-making and post-merger performance. Specifically, it examines whether common institutional ownership can reduce the probability of value-destructive acquisitions, thereby improving overall M&A performance.

This study selects China’s emerging market as the context for three key reasons. First, common institutional ownership in China differs significantly from that in developed capital markets. For instance, in the United States, institutional investors account for 43% of market capitalization, while in China, they represent only 11.6%.Footnote 2 This structural difference underscores the significance of the governance effect of common institutional ownership in China’s context for scholarly inquiry. Second, China’s capital market is characterized by strong government intervention, complex state-owned enterprise structures, and relatively weak legal protections for investors (Jiang and Kim, 2020), in stark contrast to the greater market autonomy and institutional maturity found in Western economies. This institutional backdrop may make the governance role of common institutional ownership increasingly complex and context-dependent. Lastly, corporate M&A in China are often driven by strong policy directives rather than being solely based on market efficiency or corporate strategy, resulting in acquisition dynamics that differ significantly from those in Western markets. Therefore, examining the impact of common institutional ownership on M&A in China provides insights into distinct governance mechanisms and offers valuable perspectives for institutional development in emerging markets.

Utilizing data from Chinese A-share listed firms between 2010 and 2021, this study explores the impact of common institutional ownership on corporate M&A. The findings indicate that common institutional ownership significantly curtails reckless acquisitions, while simultaneously improving both announcement effects and post-merger performance. The heterogeneity analysis suggests that long-term and independent institutional ownership exerts a more pronounced influence on effective M&A decision-making. Mechanism analysis identifies two key channels driving this effect: (1) an information mechanism, wherein institutions leverage M&A experience to mitigate information asymmetry, and (2) a monitoring mechanism, in which they appoint directors and curb managerial opportunism.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: First, it represents the first systematic investigation into the dual effects of common institutional ownership on M&A decision-making and performance. Unlike prior research, which has predominantly focused on value-destroying mergers (Zhu et al., 2024) or M&A performance (Brooks et al., 2018), this paper comprehensively examines the entire M&A process, providing new empirical evidence that highlights the nuanced role of common institutional ownership in corporate M&A.

Second, this study contributes to the literature on the governance effects of common institutional ownership. Despite ongoing academic debates regarding whether common institutional ownership exerts a positive governance effect (He and Huang, 2017) or a negative collusion effect (Azar et al., 2018), this paper investigates the role of common institutional ownership in both M&A decision-making and performance enhancement. By developing explanatory mechanisms based on information and governance effects, this study provides new evidence supporting the positive governance effects of common institutional ownership.

Third, this study offers new empirical evidence from China on how common institutional ownership enhances corporate M&A value. While prior research has primarily focused on capital markets in Europe and the United States, China’s capital market is distinguished by unique institutional features, including high ownership concentration and the separation of control rights from cash flow rights for major shareholders. These distinctive features lead to specific governance challenges. Common institutional ownership exhibits distinct governance effects in the Chinese market, and the results of this study highlight its role as an external governance mechanism, thus complementing Brooks et al.'s (2018) research on the governance role of common institutional ownership.

Literature review and hypotheses

Common institutional ownership: economic impact and M&A

Previous studies on the economic consequences of common institutional ownership primarily focus on intra-industry common ownership, emphasizing its dual governance and collusion effects. In terms of governance effects, common institutional investors can establish collaborative governance mechanisms through cross-company shareholding within the same industry, thereby enhancing their monitoring capabilities. Because of the alignment of interests between common institutional investors and their portfolio companies, these investors are highly incentivized to uncover and communicate information, thus mitigating information asymmetry and enhancing corporate transparency (Ramalingegowda et al., 2021). Furthermore, by leveraging their expertise and governance experience, common institutional investors play an active role in corporate governance. For instance, He et al. (2019) found that common institutional investors tend to oppose CEO proposals, fulfilling their oversight function. Their governance effects further extend to promoting improvements in market share and innovation productivity (He and Huang, 2017; Ding, 2023), curbing opportunistic behavior (Dai et al., 2024), increasing green investment (Lu et al., 2024), and enhancing corporate ESG performance (Schiehll and Kolahgar, 2024).

In contrast, the collusion effect suggests that common institutional investors may facilitate information exchange and resource sharing between companies within the same industry, potentially leading to market governance failure or inefficiency (Azar et al., 2018). For example, He and Huang (2017) argue that common institutional investors may undermine market competition by fostering collusive behavior. Azar et al. (2018) further found that these investors could distort market pricing mechanisms by forming strategic alliances, potentially resulting in higher product prices.

Unlike studies on cross-industry common ownership, there is a limited body of literature examining the economic impact of common ownership between the two parties involved in a transaction. For example, institutional investors holding shares in both sides of a supply chain transaction can reduce transaction costs and stabilize the supply chain (Freeman, 2023). Some research suggests that investors holding shares in both parties of a M&A may drive value-destroying deals to maximize portfolio returns (Matvos and Ostrovsky, 2008). However, Brooks et al. (2018) challenge this view, showing that common institutional investors can enhance M&A performance by reducing the acquisition premium.

In summary, existing research primarily focuses on the economic consequences of cross-industry common ownership, emphasizing the dual roles of common institutional ownership in governance and collusion (He and Huang, 2017; Azar et al., 2018). While a few studies examine the impact of common ownership between parties in a transaction, the debate continues regarding its effectiveness in enhancing M&A performance (Matvos and Ostrovsky, 2008; Brooks et al., 2018). However, the existing literature is largely limited to single-scenario analyses and has not fully explored the dual functions and mechanisms of common institutional ownership throughout the entire M&A process. Therefore, this paper adopts a comprehensive approach to the M&A process, systematically investigating the dual roles of common institutional ownership in pre-decision constraints and post-merger performance. This study not only clarifies the governance mechanisms of common institutional ownership but also makes a significant contribution to the field, broadening the scope of research on its impact on corporate behavior.

Common institutional ownership and M&A

Corporate M&A inherently carries high risk and uncertainty, with more than half of M&A transactions failing to create value for companies (Sirower and O’Byrne, 1998), and some even resulting in value destruction (Bae et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2024). The primary causes of these failures include information asymmetry before the merger (Ahern and Harford, 2014), improper target selection (Palepu, 1986), and ineffective resource integration, which all hinder value creation in M&A. Among these factors, significant information asymmetry in M&A transactions is a major barrier to value realization. Information asymmetry not only heightens the risk of M&A failure but also creates opportunities for insiders to exploit minority shareholders. In China, more than 51.2% of M&A transactions involving listed companies fail to create value, often leading to a reduction in company value (Zhu et al., 2024). Consequently, addressing information asymmetry and improving M&A performance have become central concerns in M&A research.

As a crucial governance mechanism, common institutional ownership plays a significant role in mitigating information asymmetry and improving M&A performance through its informational advantages and governance capabilities (Irani et al., 2023). By holding stakes in multiple companies, common institutional investors gain access to private information from various firms, reducing information asymmetry in M&A and acting as information bridges that facilitate knowledge sharing between companies (Park et al., 2019). This information transmission mechanism is especially critical in the target industry, as it helps reduce uncertainties in target selection and mitigate industry risks, thereby improving M&A performance. Additionally, common institutional ownership influences corporate decision-making through mechanisms such as board appointments and voting (He et al., 2019), while mitigating managerial opportunism and short-term profit-seeking behavior (Zhou et al., 2025). These actions lead to more informed M&A decisions and the creation of merger value.

The informational and experiential advantages of common institutional ownership are critical drivers of its governance effectiveness. On one hand, its industry-specific informational advantage allows common institutional ownership to select M&A targets with greater accuracy, reducing the likelihood of misguided acquisitions. Studies indicate that selecting the right acquisition targets is essential for enhancing merger value (Palepu, 1986), and high-quality targets are crucial for improving M&A performance. By leveraging its deep industry knowledge, particularly its insights into potential targets, common institutional ownership helps mitigate information asymmetry in M&A decisions, improving target selection accuracy and reducing inefficient acquisitions. Conversely, during the post-merger integration phase, common institutional ownership utilizes its industry governance advantage to enhance integration efficiency with the target company’s industry, thereby generating merger synergies (Brooks et al., 2018).

Additionally, grounded in signaling theory, common institutional ownership accumulates significant M&A experience through sustained investments. This experience includes both the evaluation and management of acquisition deals, as well as best practices for post-merger integration. By leveraging this experiential advantage, common institutional ownership can effectively guide companies in making more informed acquisition decisions and provide strategic support during the integration phase. Through its informational influence, common institutional ownership transfers accumulated M&A experience and industry knowledge to corporate decision-makers, reducing information asymmetry in target selection, lowering transaction risks, and ultimately enhancing merger value (Zhu et al., 2024).

The governance advantages of common institutional ownership play a pivotal role in overseeing M&A decisions and enhancing merger value. Common institutional investors possess both the capacity and motivation to engage in corporate governance, effectively overseeing decisions made by major shareholders and management (Park et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2018). Due to their typically larger stakes and diverse investment portfolios, common institutional investors can leverage accumulated management experience to conduct in-depth analyses of M&A transactions, thereby encouraging more rational decision-making by management. Additionally, their extensive governance experience enhances the effectiveness of supervision (Kang et al., 2018). To enhance their governance role, common institutional investors can participate directly in corporate governance by appointing directors (Zhou et al., 2025), thus improving the quality of M&A decisions. This governance experience, particularly within peer companies, can be effectively transferred, reducing supervision costs. Furthermore, to optimize portfolio returns, they can curb opportunistic behavior from major shareholders (Zhou et al., 2025), such as using M&A for rent-seeking or blindly expanding business empires, ensuring that M&A decisions align with the company’s long-term value creation objectives. Thus, by enhancing supervisory governance, common institutional ownership not only constrains M&A decisions but also improves merger quality, ultimately enhancing merger value (Zhu et al., 2024). Based on these insights, we propose the research hypothesis H1a:

H1a: Common institutional ownership has a positive M&A effect, reducing the probability of inefficient M&A and enhancing merger performance.

However, the governance role of common institutional ownership is not always advantageous. The ability of common institutional ownership to actively participate in corporate governance and enhance M&A value is largely contingent upon its willingness to engage in governance. According to the “ineffective supervision” hypothesis, institutional investors may fail to provide effective governance due to their short-term profit-seeking tendencies (Parrino et al., 2003). These investors often adopt an “exit strategy,” selling stocks when company performance deteriorates rather than actively engaging in corporate governance (Hansen and Lott, 1996). Moreover, because common institutional investors hold stakes in multiple companies, their limited time and attention may further undermine the effectiveness of supervision (Kempf et al., 2017), limiting their ability to focus adequately on individual firms’ M&A decisions and, consequently, diminishing their capacity to enhance M&A performance.

The competition-collusion hypothesis posits that common institutional investors prioritize optimizing the overall value of their investment portfolios rather than maximizing individual firm profits. Therefore, they are motivated to encourage firms to reduce excessive competitive strategies and avoid a “mutual destruction” scenario (Cheng et al., 2022). Simultaneously, due to potential conflicts of interest, common institutional investors may facilitate the formation of alliances between firms to increase market share and bargaining power, thereby seeking collusive advantages (Azar et al., 2018). As market competition diminishes, firms become less reliant on M&A to strengthen their competitive position. Under such conditions, the M&A experience and industry advantages of common institutional owners may become profit channels, where collusion with management results in unnecessary M&A decisions aimed at fulfilling management’s desire to create a “business empire,” ultimately leading to blind M&A that fail to enhance performance.

H1b: Common institutional ownership has a negative M&A effect, increasing the probability of inefficient M&A and reducing merger performance.

Data and methodology

Data and sample selection

This study uses data from Chinese A-share listed companies for the period 2010–2021. The sample excludes firms in the financial sector, ST companies, observations with missing variables, and firms with a debt-to-asset ratio exceeding 1. All variables were winsorized to mitigate the effects of outliers. After these adjustments, the final sample includes 37525 observations, of which 6976 pertain to valid merger performance. Data on merger transactions, common institutional ownership, and financial information for the listed companies were obtained from the CSMAR database.

Methodology and variable

To test hypothesis H1, this study examines the effect of common institutional ownership on corporate M&A across the entire M&A process, structured in two stages. The first stage focuses on the pre-merger decision-making process, examining how common institutional ownership influences the likelihood of a merger (MA). In the second stage, among firms that have completed a merger (MA = 1), further investigates the effect of common institutional ownership on the announcement effect (CAR) and merger performance (ΔROA). To conduct the empirical tests, the following regression models are specified.

Dependent variables

Merger probability (MA): following Blouin et al. (2021), the occurrence of a merger in a specific year is defined as a binary variable, where a value of 1 indicates that a merger occurred, and 0 indicates otherwise. Since merger probability is a binary variable, the Logit model is employed for estimation.

Merger announcement effect (CAR): an event study methodology is used to assess the market’s reaction to the merger announcement (Adra and Barbopoulos, 2023). An event window of three days before and after the announcement ([−3,3]) is defined to calculate the cumulative abnormal return (CAR[−3,3]), capturing the market’s response to the merger announcement.

Merger performance (ΔROA): the change in return on assets (ROA) over a one-year period following the merger announcement is used as a measure to evaluate the merger’s effect on the company’s operational performance in the medium term.

Independent variables

Common institutional ownership (Cross) follows the approach of He et al. (2019), defining it as the scenario where institutional investors hold at least 5% stakes in companies within the same industry. This ownership is measured by the shareholding ratio of institutional investors (Cross). Specifically, the shareholding ratio (Cross) is calculated as the average ownership percentage of institutional investors in the listed company, plus one, followed by taking the natural logarithm of the result.

Control variables

Based on studies examining the factors influencing merger performance (Goodman et al., 2014), we include control variables to account for company financial characteristics and corporate governance features. The model also includes industry and year fixed effects. The definitions of the key variables are listed in Table 1.

Empirical results and analysis

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics. The mean merger probability (MA) is 0.466, suggesting that 46.6% of listed companies engage in mergers, reflecting the high frequency of mergers in the Chinese capital market. The mean short-term merger performance (CAR) is 0.009, with a maximum of 0.391 and a minimum of −0.271, showing substantial variation in short-term performance. The mean long-term merger performance (ΔROA) is −0.018, suggesting that most companies experience negative performance in the long term, consistent with literature indicating that mergers often lead to value destruction (Zhu et al., 2024). The mean value of Cross is 0.293, reflecting a relatively low average stake in common institutional ownership. The statistical characteristics of the other control variables align with those in existing literature.

Impact of cross on M&A

Table 3 presents the effect of common institutional ownership on corporate M&A. Column (1) indicates that when the dependent variable is merger probability (MA), the coefficient of Cross is −0.109, statistically significant at the 1% level. This implies that common institutional ownership significantly reduces the likelihood of a merger. Columns (2) and (3) focus on the sample of completed mergers (MA = 1) and demonstrate that common institutional ownership has a positive and statistically significant effect on both the merger announcement effect (CAR) and long-term merger performance (ΔROA). Additionally, the results of the control variables indicate that company characteristics and governance structures influence merger behavior and performance, consistent with prior research (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Moeller et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2010).

Economically, a one-unit increase in common institutional ownership leads to a 10.9% reduction in merger probability, a 0.5% increase in the merger announcement effect, and a 0.4% improvement in merger performance. While the regression coefficients appear small, the average common institutional ownership is ~34% (as shown in Table 2, where the mean value of 0.293 corresponds to an ownership of e0.293 − 1). Therefore, while individual effects may be modest, their aggregate impact on large-scale merger transactions remains economically significant. Overall, common institutional ownership reduces the likelihood of inefficient mergers while significantly improving both the merger announcement effect and merger performance, thus supporting hypothesis H1a. These findings suggest that common institutional ownership reduces the risk of inefficient mergers by leveraging informational and experiential advantages, while enhancing merger announcement effects and performance through effective oversight. The underlying mechanism will be explored further in the subsequent analysis.

Endogenous tests

Heckman two-stage model

In practice, firms may exhibit selective tendencies when deciding whether to engage in M&A. Firms with specific characteristics, such as size and profitability, may have a higher propensity to engage in M&A, which could introduce sample selection bias. To accurately assess the impact of common institutional ownership on merger performance and avoid misattributing performance improvements solely to the reduction of inefficient mergers, this study employs the Heckman two-stage model to address endogeneity. In the first stage, the model estimates the probability of engaging in a merger, accounting for selection bias. In the second stage, the analysis incorporates the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) as a control variable to account for selection bias in the estimation of merger performance. Table 4 presents a significant IMR coefficient, confirming the presence of sample selection bias. After accounting for selection bias, the results remain consistent, further reinforcing the robustness of the findings.

Instrumental variable method

To further address endogeneity concerns, this study uses stock index changes as an instrumental variable (Crane et al., 2016). First, inclusion in the CSI 300 index is significantly correlated with common institutional ownership, satisfying the instrument’s relevance condition. Second, CSI 300 inclusion is exogenous to firms’ merger decisions and performance, thus satisfying the exogeneity condition. The instrumental variable IV300 is defined as an indicator of whether a firm’s stock is added to the CSI 300 index. IV300 equals 1 if a firm is added to the index and 0 otherwise.

The regression results are shown in Table 5. Column (1) reports the first-stage regression results, revealing a significantly negative coefficient for IV300, indicating a negative correlation between stock index changes and common institutional ownership. The validity test results show a p-value near zero and an F-value exceeding 10, ruling out concerns of exogeneity violations and weak instrument bias. Column (2) reports the second-stage regression results, which are consistent with the baseline findings, reaffirming that even after addressing endogeneity, common institutional ownership positively affects corporate mergers.

Robustness tests

Replace variable

First, we replace the common institutional ownership ratio (Cross) with the common institutional ownership connection degree (Cross_con) as the explanatory variable. Cross_con is defined as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of firms with shared common institutional investors. Simultaneously, we modify the dependent variables to improve robustness. (1) The number of acquisitions (MA_num) replaces the acquisition probability (MA) to capture the frequency of acquisitions per firm during the sample period. (2) The event window is extended to [−30,30] to capture the market’s response to acquisition announcements, replacing the original announcement effect (CAR) with CAR[−30,30]. (3) Long-term merger performance is assessed using the Buy-and-Hold Abnormal Returns (BHAR) method (Dutta et al., 2013), measuring BHAR over the 12 months following the acquisition announcement.

Column (1) of Table 6 presents the regression results using Cross_con, which align with previous findings, further emphasizing the positive effect of common institutional ownership connection degree on acquisition behavior. In column (2), after substituting the dependent variable, the estimated coefficient of Cross remains in line with previous results. These findings suggest that, regardless of changes in the measurement methods for both explanatory and dependent variables, common institutional ownership continues to have a positive impact on M&A.

Adjusting the fixed effects

Regional economic disparities can impact corporate merger decisions, with mergers being more frequent in economically developed areas. To address potential bias from regional economic fluctuations, the baseline regression includes city-year interaction fixed effects, controlling for unobserved heterogeneity and other confounding factors. Column (1) of Table 7 indicates that, after controlling for city-year interaction fixed effects, the estimated coefficient for Cross remains consistent, further confirming the robustness of the results.

PSM-OLS

Since common institutional ownership is unlikely to be randomly assigned across corporations, significant differences may exist between the treatment group (firms with common institutional ownership) and the control group (firms without it). To mitigate these differences and address endogeneity concerns, this study uses propensity score matching (PSM) as outlined by Appel et al. (2016). Specifically, a set of control variables serves as covariates, with a 1:5 nearest neighbor matching method applied. A regression analysis is then performed on the matched sample to improve comparability. The regression results in column (2) of Table 7 show that the estimated coefficient for Cross remains consistent with prior findings, confirming that, even after accounting for differences in common institutional ownership, the results are robust.

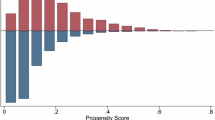

Placebo test

Theoretically, the conclusions of this study could be influenced by a placebo effect, where unobserved factors, rather than common institutional ownership, might drive the results. To address potential confounding effects from unobserved factors, this study conducts a placebo test following the method outlined by Cornaggia and Li (2019). Specifically, bootstrap randomization is used to assign treatment and control groups, with 500 iterations conducted to assess the statistical significance of the regression coefficients and validate the observed relationship. The test results, presented in Fig. 1, show that the T-statistics of the regression coefficients after random assignment are centered around 0, with only a small proportion exceeding 1.65. This suggests that no statistically significant relationship exists between common institutional ownership and corporate M&A (MA/CAR/ΔROA) under random assignment, which further supports the robustness of the prior regression findings.

Heterogeneity analysis

Long-term or short-term

Bushee (1998) suggests that long-term investors focus on a company’s sustained growth, enabling them to engage more effectively in corporate governance and reduce managerial opportunism. As a result, long-term institutional investors tend to exert greater influence and are more motivated to supervise, allowing them to play a more active role in governance. Based on a holding period of more than four quarters, we classify institutional investors as long-term (Long = 1) or short-term (Long = 0). We then introduce an interaction term between common institutional ownership and holding period (Long*Cross) in models (1) and (2) to examine the effect of long-term common institutional ownership on M&A decisions.

The regression results in column (1) of Table 8 indicate that when the dependent variable is acquisition probability, the estimated coefficient for Long*Cross is significantly negative at the 1% level, suggesting that long-term common institutional ownership reduces the likelihood of an acquisition. When the dependent variables are the acquisition announcement effect and acquisition performance, the estimated coefficient for Long*Cross is significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that long-term common institutional ownership enhances the market response to the acquisition announcement and improves acquisition performance. These findings suggest that long-term common institutional ownership improves the quality of acquisition decisions through more active governance participation, reduces irrational acquisition behavior, and ultimately enhances acquisition value.

Independent or non-independent

Chen et al. (2007) argue that improving corporate M&A performance depends on whether institutional investors can independently influence corporate governance. Consequently, this paper further examines the impact of independent versus non-independent common institutional ownership on corporate M&A activities. Specifically, we classify securities firms, social security funds, and Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) as independent institutional investors (Inde = 1), while insurance companies, trust companies, and commercial banks are categorized as non-independent institutional investors (Inde = 0). Building on the original model, we include an interaction term between common institutional ownership and investor independence (Inde*Cross) to explore the effect of independent institutional investors on M&A governance.

The regression results in column (2) of Table 8 indicate that the coefficient of Inde*Cross is significantly negative in the acquisition probability regression, while it is significantly positive in the acquisition announcement effect and acquisition performance regressions. This suggests that independent common institutional investors play a more effective governance role by mitigating inefficient acquisitions and enhancing both the acquisition announcement effect and acquisition performance. These findings reinforce the role of common institutional ownership in strengthening supervisory mechanisms and highlight the critical importance of investor independence in M&A governance.

Mechanism tests

The baseline regression results suggest that common institutional ownership positively influences M&A. However, what underlying mechanisms drive this effect? Heterogeneity analysis suggests that institutional investors with long-term holdings acquire valuable firm- and industry-specific information, helping to reduce information asymmetry and enhance M&A decision-making effectiveness. Furthermore, independent institutional investors possess stronger oversight capabilities, enabling them to curb managerial opportunism and ensure that M&A decisions align with shareholder interests. Building on this theoretical framework, this study further investigates the mechanisms underlying common institutional ownership, emphasizing both information and governance channels (see Fig. 2).

Information mechanism

Common institutional ownership offers advantages in information acquisition and experience, enabling more accurate assessments of a target’s true value through access to private information on M&A deals. This mitigates information asymmetry, lowers the risk of selecting unsuitable targets, and decreases the likelihood of ill-considered mergers. Furthermore, throughout the M&A integration process, the distinct M&A experience of common institutional owners enhances integration efficiency and strengthens governance synergies (Brooks et al., 2018). Therefore, the beneficial impact of common institutional ownership on M&A is likely driven primarily by the information mechanism, wherein accumulated knowledge and experience are transmitted to the acquiring firm. The information mechanism can be categorized into two aspects: (1) M&A experience, which pertains to the M&A practices accumulated by common institutional ownership within its network; and (2) information asymmetry, which reflects how common institutional ownership leverages its informational advantage to reduce asymmetry in M&A transactions.

M&A experience

According to imprinting theory, common institutional investors accumulate extensive M&A experience over time, gradually internalizing it as a distinctive governance capability. If a company held by common institutional investors has previously engaged in M&A, the institutional investor may transfer its accumulated M&A experience from prior transactions to its portfolio company, thereby providing valuable guidance for acquisition decisions. The M&A experience of common institutional ownership (Cross_Exp) is defined as the number of acquisitions undertaken by other companies within the same institutional investor’s portfolio network over the past five years. To examine the M&A experience mechanism, we conduct a regression analysis. The results presented in Table 9 indicate that the M&A experience of common institutional ownership significantly decreases acquisition likelihood while enhancing both the merger announcement effect and acquisition performance. These findings further validate that the M&A experience accumulated by common institutional ownership positively influences acquisition decisions and outcomes, reaffirming the effectiveness of the M&A experience mechanism.

Degree of information asymmetry

Common institutional investors, through their long-term investment practices, accumulate extensive industry knowledge, particularly critical insights into the industries of potential acquisition targets (Ramalingegowda et al., 2021). During the acquisition decision-making stage, these investors leverage their informational advantage to mitigate asymmetry more effectively, thereby enhancing the quality of acquisition decisions. In the post-acquisition integration phase, common institutional investors further utilize their industry-specific informational advantage to enhance integration efficiency, thereby boosting acquisition performance.

To test this mechanism, we adopt the methodology of Amihud et al. (1997), Amihud (2002), and Pástor and Stambaugh (2003), selecting three proxies for stock liquidity: liquidity ratio, illiquidity ratio (ILL), and return reversal rate (GAM). These indicators capture distinct dimensions of stock liquidity, which is closely related to information asymmetry. Following Hao et al. (2024), we apply principal component analysis (PCA) to these variables to construct a composite information asymmetry index (ASY). Based on the median value of the ASY, we classify the sample into high and low information asymmetry groups and perform subgroup regressions accordingly.

The regression results are presented in Table 10. In Column (1), the coefficient of Cross in the high information asymmetry group (−0.099) is larger in absolute magnitude than that in the low group (−0.084), with the difference being statistically significant at the 1% level (Chow test, p < 0.01). In Column (2), both coefficients are significant at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively, and the Chow test again confirms a significant difference (p < 0.01). In Column (3), only the coefficient in the high information asymmetry group is statistically significant, and the Chow test indicates a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.01). These results suggest that common institutional ownership is more effective in governance under conditions of higher information asymmetry, thereby supporting the information-based mechanism.

Governance mechanism

The governance advantages of common institutional ownership strengthen oversight of acquisition decisions, thereby increasing acquisition value. Common institutional investors not only actively participate in corporate governance but also indirectly shape M&A by curbing the influence of controlling shareholders. Therefore, we classify the governance mechanism into two key pathways: (1) direct oversight through board appointments and (2) reducing opportunistic behavior by restricting managerial self-interest.

Board appointments

One of the primary mechanisms through which common institutional ownership influences governance is direct supervision, particularly via board appointments (Zhou et al., 2025). To quantify this effect, we construct a variable representing the number of directors appointed by common institutional investors (DJG). Based on prior research (Zhou et al., 2025), we define an appointed director as one who concurrently serves on both the company’s board and that of the institutional investor. Regression results in Table 11 indicate that a higher number of board appointments by common institutional investors (DJG) significantly reduces the likelihood of M&A while improving market reactions to acquisition announcements and overall acquisition performance. This finding suggests that a higher number of directors appointed by common institutional investors strengthens supervisory oversight of corporate M&A decisions, ultimately improving acquisition performance. This result confirms the effectiveness of the board appointment mechanism.

Curb opportunism

Beyond direct participation in governance through board appointments, common institutional investors actively monitor and constrain the opportunistic behaviors of controlling shareholders, thereby strengthening the positive effects of M&A. First, common institutional investors with larger equity stakes are more inclined to actively engage in corporate governance to enhance value creation. Second, compared to other shareholders, they wield greater influence in monitoring and restricting the actions of controlling shareholders, thereby effectively mitigating tunneling behavior (Zhou et al., 2025). Therefore, constraining the opportunistic behavior of controlling shareholders serves as a crucial channel through which common institutional ownership exercises its governance influence in M&A. Prior research indicates that controlling shareholders’ opportunistic behavior is often subtle, frequently executed through related-party transactions that erode corporate interests.

Following Huang et al. (2025), we adopt the ratio of the total value of related-party transactions involving goods or services to total assets as a proxy for managerial tunneling behavior (Tunnel). A higher value of this variable indicates a greater propensity for management to expropriate corporate resources via related-party transactions, reflecting stronger opportunistic motives. Based on the median value of this measure, we partition the sample into high and low opportunism groups and perform subgroup regressions accordingly.

The regression results are presented in Table 12. In Column (1), the coefficient of Cross in the high-opportunism group is −0.112, which is greater in absolute magnitude than that in the low-opportunism group (−0.108), with the difference being statistically significant at the 1% level (Chow test, p < 0.01). In Column (2), both coefficients are statistically significant—at the 1% level for the high-opportunism group and at the 10% level for the low-opportunism group—with the Chow test again indicating a significant difference at the 1% level. In Column (3), only the high-opportunism group has a statistically significant coefficient, while the low-opportunism group does not; the difference remains statistically significant (p < 0.01). These results suggest that common institutional ownership plays a stronger governance role when opportunistic behavior is more pronounced, thereby supporting the governance mechanism.

Conclusion

Economic interconnections stemming from common institutional ownership among companies are especially prevalent in capital markets. However, existing research on their economic implications remains debated, primarily centering on governance versus collusion effects. Drawing on M&A data from the Chinese capital market, this study systematically examines the influence of common institutional ownership on corporate M&A and its underlying mechanisms. The findings reveal that common institutional ownership markedly decreases the likelihood of inefficient M&A while improving both M&A announcement effects and overall performance, thereby reinforcing the governance effect perspective. Further analysis suggests that long-term holdings and independently governed institutional investors more effectively exert governance influence. Mechanism tests demonstrate that common institutional ownership enhances M&A outcomes through two primary channels: the information mechanism, which utilizes M&A experience to mitigate information asymmetry, and the governance mechanism, which encompasses board appointments and the restriction of managerial opportunism.

The findings of this study offer valuable insights into understanding and strategically leveraging common institutional ownership to address the unique governance challenges in China’s capital market. Issues such as concentrated ownership and insufficient information disclosure contribute to higher agency costs, posing substantial governance challenges for Chinese firms. First, common institutional investors, capitalizing on their informational advantages, can effectively reduce information asymmetry, curb managerial overexpansion, and improve M&A performance. Therefore, policies should encourage these investors to engage more actively in corporate governance, particularly in pivotal decisions such as M&A. Second, regulatory authorities in China should devise incentive policies tailored to the local market context, fostering the development of long-term-oriented and independently governed institutional investors while enhancing oversight to mitigate potential collusion risks. Finally, enhancing China’s information disclosure framework is crucial. A transparent information environment allows institutional investors to monitor firms more effectively, thereby contributing to the healthy development of emerging capital markets.

This study has a few limitations. First, it does not comprehensively account for corporate governance structures and managerial strategies, including shareholder composition and strategic objectives, which may significantly affect M&A decisions and performance across varying contexts. Second, due to data limitations, we are unable to analyze the differential effects of common institutional ownership across different types of M&As, such as cross-border or cross-industry mergers, which future research could explore further. Additionally, this study primarily focuses on quantitative analysis and does not include in-depth interviews or qualitative research on case firms. Future research could integrate qualitative methods to more effectively capture the practical role and challenges of common institutional ownership in M&A decision-making.

Data availability

The data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Common institutional ownership is prevalent in capital markets in Europe and the United States. He and Huang (2017) found that over 60% of companies in the U.S. capital market have common institutional investors. In China, an emerging economy, around 10% of companies have such investors (Zhu et al., 2024).

More information is available on the website W020200417335981839230.pdf (szse.cn)

References

Adams RB, Hermalin BE, Weisbach MS (2010) The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: a conceptual framework and survey. J Econ Lit 48(1):58–107

Adra S, Barbopoulos LG (2023) The informational consequences of good and bad mergers. J Corp Financ 78:102310

Ahern KR, Harford J (2014) The importance of industry links in merger waves. J Financ 69(2):527–576

Amihud Y, Mendelson H, Lauterbach B (1997) Market microstructure and securities values: evidence from the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. J Financ Econ 45(3):365–390

Amihud Y (2002) Illiquidity and stock returns: cross-section and time-series effects. J Financ Mark 5(1):31–56

Appel IR, Gormley TA, Keim DB (2016) Passive investors, not passive owners. J Financ Econ 121(1):111–141

Azar J, Schmalz MC, Tecu I (2018) Anticompetitive effects of common ownership. J Financ 73(4):1513–1565

Bae KH, Kang JK, Kim JM (2002) Tunneling or value added? Evidence from mergers by Korean Business Groups. J Financ 57(6):2695–2740

Bhaumik SK, Selarka E (2012) Does ownership concentration improve M&A outcomes in emerging markets? Evidence from India. J Corp Financ 18(4):717–726

Blouin JL, Fich EM, Rice EM, Tran AL (2021) Corporate tax cuts, merger activity, and shareholder wealth. J Acct Econ 71(1):101315

Brooks C, Chen Z, Zeng Y (2018) Institutional cross-ownership and corporate strategy: the case of mergers and acquisitions. J Corp Financ 48:187–216

Bushee, BJ (1998) The influence of institutional investors on Myopic R&D investment behavior. Accounting Rev 73:305–333

Chen X, Harford J, Li K (2007) Monitoring: which institutions matter? J Finan Econ 86(2):279–305

Cheng X, Wang HH, Wang X (2022) Common institutional ownership and corporate social responsibility. J Bank Financ 136:106218

Cornaggia J, Li JY (2019) The value of access to finance: evidence from M&As. J Financ Econ 131(1):232–250

Crane AD, Michenaud S, Weston JP (2016) The effect of institutional ownership on payout policy: evidence from index thresholds. Rev Financ Stud 29(6):1377–1408

Dai J, Xu R, Zhu T, Lu C (2024) Common institutional ownership and opportunistic insider selling: evidence from China. Pac Basin Financ J 88:102580

Ding H (2023) Common institutional ownership and green innovation in family businesses: evidence from China. Bus Strat Dev 6(4):828–842

Dutta S, Saadi S, Zhu P (2013) Does payment method matter in cross-border acquisitions? Int Rev Econ Financ 25:91–107

Edmans A, Levit D, Reilly D (2019) Governance under common ownership. Rev Financ Stud 32(7):2673–2719

Freeman, KM (2023) Overlapping ownership along the supply chain. J Financ Quant Anal 60:1–30

Goodman TH, Neamtiu M, Shroff N, White HD (2014) Management forecast quality and capital investment decisions. Acct Rev 89(1):331–365

Hansen RG, Lott Jr JR (1996) Externalities and corporate objectives in a world with diversified shareholder/consumers. J Financ Quant Anal 31(1):43–68

Hao X, Miao E, Sun Q, Li K, Wen S, Xue Y (2024) The impact of digital government on corporate green innovation: evidence from China. Technol Forecast Soc Change 206:123570

He JJ, Huang J, Zhao S (2019) Internalizing governance externalities: the role of institutional cross-ownership. J Financ Econ 134(2):400–418

He J, Huang J (2017) Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: evidence from institutional blockholdings. Rev Financ Stud 30(8):2674–2718

Hope OK, Wu H, Zhao W (2017) Blockholder exit threats in the presence of private benefits of control. Rev Acct Stud 22:873–902

Huang C, Zhou H, Norhayati WA, Saad RAJ, Zhang X (2024) Tax incentives, common institutional ownership, and corporate ESG performance. Manag Decis Econ 45(4):2516–2528

Huang H, Zhang D, Wang L (2025) Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and related-party transactions: evidence from China. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 61(2):392–405

Irani, MV, Yang, W, & Zhang, F (2023) How are firms sold? The role of common ownership. J Financ Quant Anal 1–32

Jensen MC, Ruback RS (1983) The market for corporate control: the scientific evidence. J Financ Econ 11(1):5–50

Jiang F, Kim KA (2020) Corporate governance in China: a survey. Rev Financ 24(4):733–772

Kang JK, Luo J, Na HS (2018) Are institutional investors with multiple blockholdings effective monitors? J Financ Econ 128(3):576–602

Kempf E, Manconi A, Spalt O (2017) Distracted shareholders and corporate actions. Rev Financ Stud 30(5):1660–1695

Lu C, Zhu T, Xia X, Zhao Z, Zhao Y (2024) Common institutional ownership and corporate green investment: evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 91:1123–1149

Matvos G, Ostrovsky M (2008) Cross-ownership, returns, and voting in mergers. J Financ Econ 89(3):391–403

Moeller SB, Schlingemann FP, Stulz RM (2004) Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. J Financ Econ 73(2):201–228

Palepu KG (1986) Predicting takeover targets: a methodological and empirical analysis. J Account Econ 8(1):3–35

Pástor Ľ, Stambaugh RF (2003) Liquidity risk and expected stock returns. J Polit Econ 111(3):642–685

Park J, Sani J, Shrof N, White H (2019) Disclosure incentives when competing firms have common ownership. J Acct Econ 67(2-3):387–415

Parrino R, Sias RW, Starks LT (2003) Voting with their feet: institutional ownership changes around forced CEO turnover. J Financ Econ 68(1):3–46

Ramalingegowda S, Utke S, Yu Y (2021) Common institutional ownership and earnings management. Contemp Acct Res 38(1):208–241

Schiehll E, Kolahgar S (2024) Common ownership and investor-focused disclosure: evidence from ESG financial materiality. Bus Strat Environ 34:497–515

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1997) A survey of corporate governance. J Financ 52(2):737–783

Sirower ML, O’Byrne SF (1998) The measurement of post-acquisition performance: toward a value-based benchmarking methodology. J Appl Corp Financ 11(2):107–121

Zhou F, Chen L, Zhao L, Fu X (2025) Can common institutional ownership constrain the equity pledges of controlling shareholders? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Borsa Istanbul Rev 25:311–322

Zhu S, Lu R, Xu T, Wu W, Chen Y (2024) Can common institutional owners inhibit bad mergers and acquisitions? Evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 89:246–266

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support provided by the Key Project of the Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Foundation (Grant No. 21GLA005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors’ contributions are as follows: FZ: writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization, software; LC: writing-original draft, formal analysis, and methodology; LZ: modification and optimization; XF: modification and optimization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, F., Chen, L., Zhao, L. et al. Governance or collusion? The M&A effects of common institutional ownership. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 855 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05276-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05276-y