Abstract

This study examines how social norms (SNs) influence trust in financial institutions and shape economic behavior in Ethiopia, where informal institutions such as Equb and Edir coexist with modern banking and insurance systems. This research addresses two key questions: (1) How do social norms affect economic behaviors, such as saving, investment, and institutional trust? (2) What lessons can formal financial institutions learn from the traditional economic structures? Using a mixed-methods approach, this study draws on World Values Survey (WVS) Wave 7 data (n = 1230) and 98 key informant interviews from seven Ethiopian cities. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and thematic coding of qualitative interviews. Findings indicate that 78.5% of respondents are “confirmatory,” meaning they adhere closely to prevailing social norms, while 21.5% are “non-confirmatory,” demonstrating a greater willingness to deviate from societal expectations. While economic satisfaction did not significantly differ between groups (p = 0.812), confirmatory individuals exhibited lower trust in the government (64.5%) and major banks (69.2%) than non-confirmatory individuals (72.6% and 76.5%, respectively; p = 0.015, p = 0.04). Additionally, qualitative insights reveal that confirmatory individuals hold stronger reservations toward wealth accumulation and savings, which may have implications for financial decision making. To improve financial inclusion and institutional trust, policymakers should integrate trust-building mechanisms from informal institutions, increase financial literacy, and develop more flexible banking services. Recognizing the effectiveness of Equb and Edir, formal financial institutions should adopt community-driven approaches to enhance their accessibility, reliability, and participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social norms (SNs) are widely recognized as informal rules that shape societal behavior. In Ethiopia, these norms play a crucial role in influencing economic activities and institutional trust, particularly within informal financial institutions, such as Equb and Edir. While economic institutions (EIs) are essential for development, modern financial institutions in Ethiopia often struggle with trust and accessibility despite the strong presence of indigenous financial practices (Dercon et al., 2006; Hoddinott, Yisehac (2015)).

Despite the extensive literature on the relationship between SNs and economic behavior, the extent to which SNs influence trust in formal economic institutions in Ethiopia remains underexplored. Existing studies highlight the effectiveness of informal financial systems but do not adequately explain why modern financial institutions have not gained similar trust and participation (Admassie, 1999; Kenea et al., 2020). This study seeks to fill this gap by examining how SNs shape trust and financial behavior, contributing to a broader understanding of economic participation in Ethiopia.

Social norms have been shown to influence economic decision-making globally, from savings behavior in rural India (Banerjee and Duflo, 2011) to financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018). However, little empirical work has been conducted to investigate how these norms affect trust and engagement with formal financial institutions in Ethiopia. Given that over 62% of Ethiopians reported saving money, but only 26% did so in formal institutions (Bessir, 2018), it is crucial to understand the underlying social and cultural factors shaping these behaviors.

The Ethiopian economy has undergone significant changes with increasing efforts to modernize financial services. However, understanding SNs is essential to ensuring that these modern institutions are effective, inclusive, and trusted. Without integrating insights from informal financial practices, policies aimed at financial inclusion may fail to address the real barriers preventing participation in the formal economy (World Bank, 2020).

This study aims to:

-

1.

Examine the relationship between social norms and trust in financial institutions in Ethiopia, distinguishing between formal and informal systems.

-

2.

Analyze how SNs influence financial behaviors such as savings, investment, and institutional membership.

-

3.

To identify lessons that formal institutions can learn from traditional financial systems to improve financial inclusion and trust.

Several studies have examined the impact of SNs on financial decision making (Akerlof, 1980; Elster, 2016). SNs shape risk perceptions, economic cooperation, and institutional trust, reducing transaction costs in some cases and discouraging individualistic financial behavior in others (Alpman, 2013). In Ethiopia, research has shown that Equb and Edir function as highly effective financial institutions, fostering trust and social capital (Pankhurst and Mariam, 2000). However, their success has not translated into greater participation in modern banks and insurance systems, indicating the persistence of cultural barriers.

Recent studies have elucidated these dynamics. Yayeh and Demissie (2025) analyzed the impact of social capital on saving behavior among members of financial cooperatives in Ethiopia’s Amhara region, finding that strong social networks positively influence savings habits. Similarly, research in sub-Saharan Africa indicates that cultural factors significantly affect financial inclusion and income inequality, with social norms facilitating or hindering access to formal financial services. Moreover, digital financial services in Ethiopia reveal a pronounced gender gap, with women facing greater financial exclusion due to restrictive social norms and limited asset ownership (Awol, 2025).

Comparative studies show that countries with strong informal financial traditions often experience low trust in formal institutions, unless deliberate efforts are made to integrate traditional practices (Collins et al., 2009). For example, in Kenya, the success of M-Pesa stems from its adaptation to existing SNs in informal savings groups (Jack and Suri, 2011). This raises the following question: Can Ethiopian financial institutions adopt similar approaches to bridge the gap between informal and formal financial systems?

To address this research problem, this study focused on the following questions:

-

1.

How do SNs affect trust in formal and informal financial institutions in Ethiopia?

-

2.

What are the key differences in financial behavior between individuals who conform to SNs and those who do not?

-

3.

What lessons can modern financial institutions learn from traditional SN-based financial practices such as Equb and Edir?

Literature review

Theoretical foundations

Social norms and economic institutions

Institutional economics posits that both formal (laws and regulations) and informal institutions (customs and social norms) shape economic outcomes (North, 1990). Social norms regulate behavior by fostering cooperation and reducing transaction costs (Elster, 2016). Theoretical perspectives suggest that social norms can either support or hinder economic efficiency, depending on their alignment with economic institutions (Gradstein et al., 2006). Additionally, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) argued that inclusive institutions foster economic development, while extractive institutions stifle growth. Social norms determine the extent to which institutions can be inclusive or exclusive, thus influencing access to financial services and economic mobility.

Trust and financial behavior

Trust, which is a fundamental aspect of social norms, plays a crucial role in financial institutions. Knack and Keefer (1997) find that societies with higher levels of trust tend to have stronger financial institutions. Similarly, Eriksson (2015) highlights that trust in economic institutions fosters financial participation and compliance with regulatory frameworks. Conversely, when social norms contradict formal financial structures, trust in financial institutions declines, limiting economic development(Dequech, 2006).

Fukuyama (1996) further shows that trust-based networks reduce reliance on costly enforcement mechanisms and promote more efficient financial transactions. Recent research by Algan and Cahuc (2010) underscores the fact that trust influences macroeconomic stability, financial intermediation, and investment decisions, demonstrating the far-reaching implications of social norms on economic outcomes.

Empirical studies

Social norms and economic development

Early works, such as Weber (1930) study of Protestant ethics, argue that cultural and social norms influence economic prosperity. Inglehart and Baker (2000) later confirmed this by showing that shifts in values toward rationality and trust correlate with economic growth. Conversely, Lawrence (2000) contends that deeply embedded social norms can hinder development, particularly in regions where traditional norms limit market efficiency and innovation.

Recent evidence from Nunn and Wantchekon (2011) indicates that the historical experiences of coercion and mistrust can lead to persistent economic underdevelopment, emphasizing the long-term effects of cultural norms on economic trajectories. Putnam (2000) highlighted that social capital, shaped by norms and trust, is a key determinant of regional economic disparities and institutional performance.

Social norms and financial institutions

Alpman (2013) explores how disobeying inefficient social norms can lead to better financial outcomes. Using data from the World Values Survey (WVS), he found that individuals who reject restrictive norms experience higher income growth and financial inclusion. Similarly, Stratton and Datta Gupta (2021) linked social norms with bargaining power, indicating that adherence to traditional norms can limit participation in formal financial systems. Additional studies by Banerjee and Duflo (2011) highlight that informal lending norms shaped by trust and reciprocity often substitute for formal financial services in developing economies, leading to inefficiencies in financial inclusion. In Ethiopia, traditional savings groups (Equb) function based on the long-standing social norms of trust and obligation, which both facilitate and constrain access to financial services.

Ethiopian context

Studies in Ethiopia highlight the role of social norms in shaping economic institutions. Crummey (2000) documented historical land tenure systems that shaped economic behavior, while Teshome et al. (2016) examined how social capital influences land management practices. More recently, Oniki et al. (2020) demonstrated how social norms impact participation in communal land distribution programmes. Additionally, Mogues (2006) examined the role of social capital in resilience to economic shocks and found that informal safety nets driven by cultural norms play a critical role in financial stability.

Studies on the financial sector in Ethiopia indicate a gap between social norms and formal institutions. Meijerink et al. (2014) found that the establishment of the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) disrupted traditional trust-based trading networks, leading to changes in financial interactions. Gudata (2020) highlights the economic consequences of social norms related to khat consumption, showing their negative impact on household savings and financial stability. Emerging research by Kenea et al. (2020) suggests that digital financial inclusion efforts in Ethiopia face resistance owing to entrenched social norms regarding cash-based transactions and skepticism toward technology-driven banking.

Benchmark comparisons

Lessons from East Asia demonstrate how integrating social norms into economic policies can foster development. Studies by Lajčiak (2017) and Cho (2021) revealed that in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, economic policies succeeded because they were aligned with existing social norms. These nations leverage traditional values to build trust in their financial systems and enhance economic participation. Additional research by Meek et al. (2010) highlights how social norms influence entrepreneurship and demonstrates that collective trust and community networks are central to business success. In contrast, research on sub-Saharan Africa suggests that deeply embedded communal norms sometimes deter risk-taking and entrepreneurial activities, limiting economic diversification (Hoff and Stiglitz, 2016).

In general, the literature underscores the dual role of social norms in either facilitating or hindering trust and economic behavior in financial institutions. While positive norms can enhance financial participation and institutional trust, restrictive or inefficient norms can obstruct economic progress. Future research should explore strategies to align social norms with financial policies in order to foster sustainable economic development in Ethiopia.

Research methodology

Research approach and design

This study is descriptive and employs a mixed-methods design that integrates both quantitative and qualitative data from primary and secondary sources. Primary quantitative data were derived from the 2020 World Values Survey (WVS) for Ethiopia (Haerpfer et al. (2020); Inglehart et al. (2014)), while qualitative insights were obtained through semi-structured interviews with 98 key informants and a comprehensive review of secondary literature. The WVS data were collected in only two waves (2007 and 2020); however, since we only focused on the relationship between social norms and trust in both formal and informal financial institutions and their impact on financial behaviors such as savings and investment, we only focused on the recent data from the 2020 survey. As shown in Fig. 1, data were collected all over Ethiopia. To strengthen and triangulate the findings, interviews were conducted to uncover the underlying reasons for quantitative trends. While interview data were collected from various regions across Ethiopia, the Tigray region was excluded because of conflict and insecurity at the time of data collection; however, the WVS data covered all regions, ensuring broader geographical representation.

This map illustrates the distribution of households surveyed in the 2020 World Values Survey (WVS) wave 7 across various Ethiopian regions. The study area excludes some parts of the country, for instance, the Tigray region, due to conflict at the time of data collection, focusing on major cities and towns with diverse economic institutions.

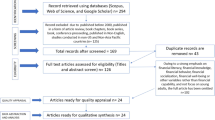

Sampling and data collection method for the KII

Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were conducted using purposive sampling with clearly defined selection criteria (See Appendix 1), ensuring geographical and diverse socioeconomic background representation and informed consent. Participants included senior bank managers, senior insurance company managers, leaders of community-based organizations (CBS) (e.g., Edir or Afosha and Equb), and community members from diverse economic backgrounds. All informants were required to have extensive experience in their respective fields (over 10 years for managers and over five years for CBO leaders). The 98 informants were selected from seven major Ethiopian cities: Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, Hawasa, Jimma, Dire Dawa, Harar, and Adama which are chosen for their established economic institutions and diverse populations. The interviews were conducted in 2023 using a semi-structured format that allowed in-depth exploration while ensuring consistency. Data collection continued until saturation was reached, and measures, such as member checking, peer review, and iterative sampling adjustments, were employed to minimize bias. Detailed demographic information (sex, religious background, economic status, and location) for KII participants are provided in Appendix 2.

To reduce bias that might be caused by purposive sampling and increase data quality, we followed strict steps, as illustrated in Fig. 2 below. Data collection started by obtaining an official letter from the Ethiopia Policy Study Institute (PSI), the data collectors used to contact municipalities. Then, using the clearly stated selection criteria, our data collectors began their interviews. At the same time, the municipalities provided a focal person who was well versed in the area to help our data collectors identify the community members and leaders.

Outlines the systematic steps taken for data collection and quality assurance in the study. It details the processes followed, including participant selection, data gathering methods, transcription, translation, and coding for analysis. Additionally, it highlights measures implemented to ensure data reliability, such as triangulation, peer review, and validation checks.

Data analysis methods

WVS wave 7 data were obtained from the official WVS websiteFootnote 1 and imported into STATA for quantitative analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, medians, and modes, were generated, and the significance of relationships between our dependent binary variable and various independent variables was tested using chi-square and p-values. A key challenge in our analysis was collecting, sorting, and defining variables related to social norms (SNs). Based on the frameworks of Costenbader et al. (2019) and Elster (2016), multiple SN-related variables, more than 21, from the WVS were aggregated to create a composite indicator, which was then used to classify respondents into “confirmatory” and “non-confirmatory” groups (for the details on how the analysis was made see Appendix 3) The result from this classification was further validated against self-reported adherence from the interviews.

For the interview participants, we borrowed questionnaires from the WVS and presented them at the end of the interview to help us identify whether the person was confirmatory or non-confirmatory. We asked them to rate their answer to statements such as, “It is important to this person to always behave properly; to avoid doing anything people would say is wrong” as “like me” and “not like me” (See Appendix 4 B for the full list of the indicators). This helped us to see if the person ‘behaves properly’ by doing what the community says is right, confirmatory, or sometimes does not behave ‘properly’ and follows his instinct and rationale, non-confirmatory.

Qualitative data from the interviews were transcribed, translated, and analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis. To prepare the data for analysis, the interviews were transcribed from their original format into written text and translated into English, ensuring consistency and accessibility while preserving the meaning and integrity of the participants’ responses. The translated transcripts were organized in an Excel spreadsheet for analysis, with each row representing a participant or interview segment, and columns used to record coded text segments and emerging themes. Features, such as filtering and sorting, were utilized to group similar responses and identify patterns across the dataset, facilitating a thorough and systematic coding process. Additionally, transcripts were processed using an online word cloud tool to identify key themes.

The secondary literature on indigenous economic institutions, particularly Equb and Edir, was reviewed to extract policy recommendations and lessons for modern institutions. The triangulation of the WVS data, qualitative interview findings, and secondary sources has resulted in a comprehensive and robust analysis of the interplay between social norms and economic institutions in Ethiopia.

Results

Demography and work of the respondents

The data showed that from a total of 1230 respondents, 78.53% (966) were confirmatory and 21.46% (264) were non-confirmatory to the existing SNs (See Table 1). This small group of non-confirmatory members of the community can be considered deviant. Deviating from existing community norms (Deflem, 2015). This study compares and contrasts the demography, economy, work culture, and institutional trust of these two groups in the following subsections. Moreover, we also checked the Chi-square and P value of the data to see whether there is a significant association between work-related beliefs, economic satisfaction, and the institutional trust level of respondents and their SNs, at a 5% level of significance.

The demographic composition of the study participants was similar to that of the Ethiopian population since the sampling technique used by WVS is proportional to the population of the study (PPI). The sex ratio of the survey participants was almost equal: 50.6% (622) were male and 49.4% (608) were female. We can say that there was no difference in the confirmatory level of the two sexes. In terms of residence, 75.9% (934) of the participants were from rural areas, while the remainder were from urban areas. The majority of participants were also young and married, found between the age group of 18 and 38 years old. In terms of religion, from the non-confirmatory group, 50% (132) of them are Muslim and from the confirmatory group, 50% (484) of them are from Orthodox religion. More than 50% of the participants came from the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, Oromo, and Amhara (see Table 1).

The data indicate that the majority of the respondents from both groups are employed and educated, and there is no major difference between the two groups. We only see some differences in the types of work: 31.5% (245) of the confirmatory group were government employees and 26.8% (63) for the non-confirmatory group. In addition, most of the non-confirmatory groups, 46.8% (110), are engaged in private non-profit organizations; this is only 36.2% (282) for the confirmatory group. The P value for work type was 0.013, indicating an existing relationship (see Table 2).

We also tried to identify work-related beliefs associated with gender norms. Studies show that gender attitudes are integral to understanding economic institutions and are a central component of the social norms that shape economic behavior. Gender norms not only influence the relationship between men and women, but also have a significant economic impact on employment patterns, income distribution, and the overall functioning of financial institutions (Alesina et al., 2013; Jayachandran, 2020). As shown on the Fig. 3, for the questions “men should have more right to a job than women,” and it is a “problem if women have more income than husbands” most of the confirmatory groups said “Agree,” 50.70% (489) and 48.20% (462), while most of the non-confirmatory groups “Disagree,” 56.80% (150) and 56.30% (148), respectively. The P values for these questions were 0.007 and 0.034, respectively (See Table 2).

SNs, economic well-being, and saving

Similar to SNs, to make the data on economic well-being more reliable, we merged several variables from different questions from the WVS, took the median, and generated one indicator for economic satisfaction. In the 2020 WVS, these questions included Q49 life satisfaction, Q50 financial satisfaction, and the Q288 income group. Respondents were expected to rate their answers from 1 “completely dissatisfied” with their income to 10 “completely satisfied” with their income. Based on this, we calculated the median of the three questions, which was 15.4, and generated an economic indicator called ‘economic well-being. We then divided the participants into two groups: those who were satisfied with their economy ( > 15.4) and those who were not satisfied with their economy ( < 15.4). We then compared the results with the SNs or the confirmatory level of the respondents. As shown in Fig. 4, there was no significant difference between the two groups: 50.30% (486) of the confirmatory groups were satisfied with their economy, and this was 51.10% (135) of the non-confirmatory groups. The P value is 0.812, indicating that there is no significant relationship between economic satisfaction and being confirmatory or non-confirmatory of the existing SNs. To understand the reason for this, we used KII.

In the interviews, we asked respondents various questions to see if they were satisfied with their economic status and why. Most of the respondents who responded to the SNs rating questions “like me” or those who are confirmatory, reasoned that “I am satisfied, I have everything that I need, thanks to God.” On the other hand, most of those who said “not like me” or the non-confirmatory groups tried to be more elaborative. They listed what they have, “I have a car, a house, and enough amount of money in my account…”

In addition, we identify other economy-related variables from the WVS data related to economic well-being. These include “Economic status”, “Gone without enough food to eat”, “Gone without needed medicine or treatment”, “Gone without a cash income”, and “Gone without a safe shelter”. As indicated in Table 3, similar to economic satisfaction, there was no major difference between the two groups regarding economic status and variables related to economic well-being. Economically, 21% of both groups indicated that they belonged to the upper classes of the community. However, for the lower groups, 39.70% (382) were confirmatory and 42.50% (111) were non-confirmatory, indicating little difference. Nevertheless, as indicated above in KII, a person might think and respond he is among the “upper class” while in reality only owns basic things. In addition, the table shows that the majority of both groups never or only rarely went without food, medicine, cash income, or safe shelter (see Table 3).

Savings is another important variable that directly affects the performance of economic institutions. Figure 5 presents a comparison of the savings culture of the confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups. From the confirmatory groups, 34.6% (332) and from the non-confirmatory groups, 31.1% (76) indicated that their family saved money during the past year. The majority of both groups indicated that their family “just got by”. Overall, there were no major differences between the two groups.

As shown in Fig. 6, for word clouds, the common reasons for the absence of saving among the KII participant are: “I do not have enough income”, “I don’t have the capacity”, “I don’t have additional income to be saved”, and similar others. Nevertheless, we investigated why? There was an interesting response from some non-confirmatory groups. They indicated that they would prefer to invest than save, because of the “existing economic situation.” They tried to calculate how much money they would lose if they put in banks compared to investing.

Likewise, to see the perception of money, we also asked if the accumulation of money was good or bad. From the confirmatory groups, 74.20% (49) of them said good, while from the non-confirmatory group, 84.20% (16) said good (see Table 4). To understand the reason for this, we probed why the accumulation of money is bad. Most of the confirmatory groups responded that “I have seen that money spoiled the life of its owners”, “accumulated wealth will make you greedy and pave the way for bad doings”, and “it is better to give or share for those who do not have instead of accumulating it. On the other hand, most of the non-confirmatory groups highlighted that It has to be transacted”, “It has to be used or invested”, “money has to rotate so as to benefit the economy, and “money has to flow, otherwise, it causes inflation.

To get more insight on this we have also directly asked “Do you want to be rich?” Of the confirmatory 18.50% (12) and non-confirmatory 26.30% (5) responded “No” (see Table 4). For the follow-up question, there were some summaries of the data. Most of the confirmatory groups reasoned “The rich will not inherit the kingdom of God.” “I only want to fulfil my basic needs.” “Because many rich people are greedy and don’t care about others.” “Why I care, I don’t know how many years I live.” On the other hand, most of the non-confirmatory groups indicated “The only thing I want is to be healthy.” “I am not eager to be rich and I strictly condemn the unhealthy practices of being rich.” “I already have what I want”. and “I want to be moderate or balanced in terms of my income.”

SNs and institutional trust

In addition to work and economic well-being, the development of economic institutions also depends on the trust of the community that uses them, which is essential for their development (Buriak et al., 2019). WVS Wave 7 directly asked the respondents to indicate whether they trusted an organization. A list of institutions such as labor unions, government, major companies, banks, insurance, and international organizations was provided with a choice of “Trust” or “Not Trust.” Interestingly, although the difference is smaller in percentage, in all instances, these institutions are more trusted by the non-confirmatory groups of the community than by the confirmatory ones, as shown in Table 5. For instance, labor unions and banks are trusted by 51.80% (421), 58.20% (131), and 91.80% (879) 93.00% (240) of the confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups, respectively.

In addition, the P values for the government and the World Bank are significant, indicating that the relationship between SNs and trust for these variables is statistically significant. Many studies have shown that trust plays an important role in the development of economic institutions (Baidoo and Akoto, 2019; Murphy, 2006; Williamson, 1993). Although the reason for less trust from the confirmatory groups and how the SNs are causing mistrust require further investigation, our interview data show that the confirmatory groups prefer more traditional institutions. From the interview participants, 72.41% (21) of the confirmatory groups indicated that they were members of traditional institutions, such as Equb and Edir; this was 63.33% (19) for the non-confirmatory groups (See Table 4).

As shown in Table 4, we also asked the interview participants whether they trusted economic institutions, such as banks and insurance. More than 90% of both groups indicated that they had no issue-trusted banks. For insurance companies, approximately 80% of both groups indicated that they did not have trust issues. Rather, some informants highlighted that, “it is them [banks and insurances] who don’t trust us.” Because they have a lot of procedures and always asks for collateral to give a small amount of money. However, for those who don’t trust modern EIs the common reasons mentioned includes: “They are ineffective and bureaucratic.” “Because they are corrupt.” Above all, almost all informants raised the limitations on the amount of money to be withdrawn from both banks and ATM machines greatly shattered their trust level on banks. Some said, “We are not getting our money when we need it, this is shame, so why I trust them with my money?”. As a result, people resorted to informal economic institutions like Equb, particularly small traders and farmers.

Similar to trust, regarding organizational membership, the data shows a consistent difference between the confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups as shown on the on Table 6. The data shows that a larger percentage of the non-confirmatory groups are ‘active’ members of organizations such as sport or recreational, 7.90% (76) for confirmatory, and 18.30% (48) for non-confirmatory, art, and music. 14.10% (135) for confirmatory and 16.50% (43) for non-confirmatory labor unions 9.90% (95) for confirmatory and 17.20% (45) for non-confirmatory political parties 4.00% (38) for confirmatory and 7.70% (20) for non-confirmatory, and professional organizations, 6.70% (64) for confirmatory and 11.60% (30) for non-confirmatory groups. This is also true for environmental, charitable/humanitarian, self-help, and women associations: 9.20% (88) and 20.30% (53), 8.40% (80) and 18.50% (48), 13.20% (126) and 20.30% (53), and 7.70% (72) and 15.80% (41), for confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups, respectively. The only exceptions where the confirmatory groups are larger than the non-confirmatory groups in percentage are the active membership of a church (67.50%, 651) and 61.70% (163), respectively.

Discussions

The analysis of demography and work-related characteristics reveals that social norms (SNs) in Ethiopia are strongly intertwined with cultural and religious traditions. Our findings indicate that a significant proportion of respondents adhere to SNs deeply rooted in orthodox Christianity, which has long shaped Ethiopian society. This cultural legacy appears to influence occupational choices as well: confirmatory individuals tend to favor traditional income channels such as government employment, whereas non-confirmatory respondents are more inclined to pursue entrepreneurial ventures in the private nonprofit sector. This pattern suggests that adherence to established norms may reinforce conventional career paths and discourage deviation from accepted modes of economic behavior.

Moreover, work-related beliefs are significantly influenced by SNs. Our quantitative analysis shows a statistically significant relationship between normative adherence and gender-related work beliefs; for instance, confirmatory individuals are more likely to consider it problematic for a woman to earn more than her husband (p = 0.034). This finding underscores the strong influence of traditional norms on employment decisions and recruitment practices. When individuals internalize these norms, they may favor male-dominated work environments, potentially affecting household income distribution and, ultimately, the performance of economic institutions. Such entrenched beliefs, if unchallenged, can perpetuate gender inequities and hinder broader economic progress.

Turning to economic well-being and saving behaviors, our results suggest that while both confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups report similar levels of economic satisfaction, the underlying reasons differ considerably. In qualitative interviews, confirmatory respondents often attributed their satisfaction to divine providence expressing contentment with their status by invoking religious gratitude which may lead to contentment without having basic things for life and a reduced drive to improve their economic circumstances. Satisfaction with once economy without having what is important for life and enough money, will not only harm the economic efficiency of a household but also an institution and a nation in general. This can imply that the person will not work hard or struggle enough to change his condition, because he/she is already satisfied with what he/she has and thinks it is enough. This finding is consistent with Alpman (2013), who also based on WVS data and revealed that SNs play a significant role in shaping individuals’ behavior and decisions, impacting their economic efficiency and development. In contrast, non-confirmatory respondents provided more detailed accounts of their assets, such as owning a car or a house, and expressed a pragmatic preference for investment over mere saving. This divergence is further illustrated by differences in attitudes toward wealth accumulation. The study also shows that the belief that ‘money is evil’ is inculcated in most of the confirmatory groups and negatively affecting their saving culture and economic performance. They tended to view the accumulation of money negatively associating it with greed and social decay whereas non-confirmatory groups saw investment as a means to generate additional income and create employment. Although self-assessments of economic status are subject to bias, these nuanced differences in financial outlook highlight the complex interplay between SNs and economic behaviors.

Institutional trust is another critical area where SNs exert influence. Our data reveal that confirmatory groups, who rely heavily on traditional norms, exhibit slightly lower trust in modern economic institutions such as government bodies and the Banks. From among the listed more than ten organizational memberships, religious institutions are the only category where confirmatory groups outnumbered non-confirmatory groups. This suggests that social norms in Ethiopia strongly reinforce religious affiliation, shaping patterns of institutional trust and engagement. This trend may be attributed to the interplay between Ethiopian SNs and religious values, which emphasize trust in divine providence over financial institutions and foster skepticism toward unfamiliar things, including modern economic structures. Given that 97% of respondents consider God important in their lives and 78.53% adhere to confirmatory norms, financial institutions in Ethiopia face a challenge in gaining widespread trust and participation. The low trust may also stem from a preference for traditional, community-based institutions like Equb and Edir, which are perceived as more reliable and culturally resonant. These findings are in line with previous studies (Baidoo and Akoto, 2019; Murphy, 2006; Williamson, 1993) that emphasize the importance of trust in the effective functioning of economic institutions.

In summary, our findings indicate that while SNs significantly shape economic behaviors and institutional trust in Ethiopia, these effects are embedded within a broader socio-cultural and economic context. The divergence between confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups is evident in work-related beliefs, saving practices, and perceptions of wealth, with traditional norms often impeding economic dynamism. Modern economic institutions must therefore consider strategies that not only improve service delivery but also integrate lessons from indigenous institutions emphasizing trust building, flexibility, and inclusiveness—to better serve the diverse needs of the Ethiopian community. Recent studies also warn of the decline of traditional norms amidst modernization and urbanization (Yazew and Kassa, 2024), underscoring the urgent need for policies that preserve the beneficial aspects of these norms while fostering innovative, adaptive economic governance.

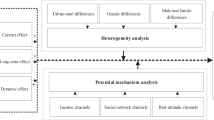

Lessons for modern economic institutions form SN based traditional informal institutions such as Equb and Edir

Various research works indicate that the indigenous economic institutions in Ethiopia are more reliable for the local community and successful not only in terms of having a large number of members, but also in effectively improving the economic well-being of their member and the community in general. To give lessons for modern EIs in Ethiopia, for this study, we only focused on Edir and Equb. These institutions are highly prevalent; more than 90% of Ethiopians joined some form of traditional savings (Equb) or informal insurance (Edir) institutions. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Ethiopian Rural Household Surveys (ERHS), 1989–2009, indicate that 85% of households in rural areas are members of an Edir, and in the central parts of Ethiopia, the number goes up to 93% (Habtu, 2012). Data from the World Bank also shows that 62% of Ethiopians reported saving money in the past year, but only 26% saved formally at the formal financial institutions (Bessir, 2018), and the rest 40% saved in informal institutions. This indicates the SN-based informal and indigenous institutions in Ethiopia are effective, efficient, active, trusted, and well-organized. Thus, there are huge lessons that the modern economic institutions in Ethiopia can learn from them. We identified at least three interrelated important lessons: trust building and reliability, flexibility and working with the vulnerable, and inclusiveness and ingenuity. As shown in Fig. 7, all lessons depend and reenforce each other and requires tangible actions from the modern EIs.

Trust building and reliability

When thinking of trust what comes to most people’s mind is trust in EIs, nevertheless, our data shows there is no issue with that. Rather it is the reverse, EIs’ trust on the community. To build trust and become reliable, and also demonstrate their trust on the community, banks and insurance companies in Ethiopia have to make their services holistic. They should not have to focus only on collecting money and making a profit. Successful informal institutions such as Edir and Equb are playing a multipurpose role in the community. Although their main objectives are risk sharing and saving, respectively, they also play other important roles. Studies show that indigenous institutions in Ethiopia like Equb, Edir, and Mahber are serving as risk coping mechanisms, giving credit services, providing labor power services, and playing a role in natural resource management, information distribution, and conflict resolution (Habtu, 2012).

The word cloud on Fig. 8 from KII data is generated from the question, what modern EIs in Ethiopia have to do to increase community trust? We can see that ‘Community work’, ‘Awareness’ and ‘Survive’ is the most visible word. They can involve in the natural resource management, health education campaigns, pure water provisions, and other activities that can benefit the community while teaching the significance of saving. They can also expand their credit services to the wider community to serve the people and to gain trust by providing money when the people need it. Moreover, they can also play a significant role in information distribution. This should not have to be just opening a Facebook page and posting, teaching, or advertising on television and radio; they must go down and physically move to the village and from house to house to teach and serve. This also helps them learn the culture and become familiar with the local community. The interview participants also indicated that ‘if people know you, they trust you, and if they trust you, they will give you, their money’.

This word cloud visualizes community members’ suggestions for actions modern economic institutions can take to enhance public trust. Prominent themes include ‘community work,’ ‘awareness,’ and ‘support,’ reflecting a desire for institutions to engage more directly with local needs beyond traditional banking services.

Indigenous institutions are also playing a very important role in economic development through collective actions. Almost half of the Edir provide loans for their members. Mahber, which is mainly a religious association, also serves as a risk-coping mechanism, provision of information, addressing manpower, and traction force (Habtu, 2012). The modern institutions in Ethiopia are providing loans only to a limited number of customers, mostly the rich, who have trade licenses and can provide collateral and diaspora who have dollar. Nevertheless, the informal institutions managed to amass mass membership using their loan mechanisms. For instance, in Equb, every member has an equal opportunity to take the money using the lottery method, but if one member informs the chair first that he or she needs the money, they will give it to him or her. The maximum requirement is to have someone from the Equb as a guarantee, which serves as collateral. This helps the member get their money when they need it.

SNs based traditional informal EIs such as Equb and Edir genuinely trust their members or customers. They established based on trust and if one of their members needs money they give loan without any collateral request. ‘Modern EIs, especially banks, have to seriously consider the issue of loans,’ said one of our informants. Anyone who saves money at a particular bank should have the right to borrow when he or she needs it. Because, as most of the informants indicated, borrowing money is the last and best option to get money when they need it. Regarding this, one informant raised an important question: ‘If they [banks] don’t trust and give me money when I need it, why do I trust them and give them my money?’ To improve this, banks have to reform their requirements to give loans. Of course, banks need a guarantee that the money they give will come back. For this, they can study and use the example of traditional informal institutions such as Edir and Equb in Ethiopia.

In addition to serving as insurance (risk coping), provision of credit, and sharing of information, Edir is also playing a role in health education, for instance HIV prevention (Pankhurst and Mariam, 2000) assisting victims during bereavement, serving as a risk-sharing mechanism, and providing health insurance (Mariam, 2003). Studies show that, of the people who joined Edir, more than 21% are already using it as health insurance, and 90% of them indicated that they are willing to use it to cover their health expenses. In addition, Edir also covers burial ceremonies, wedding expenses, house fires, and health care for its members. Generally, the indigenous institutions in Ethiopia have a remarkable role in social support, conflict resolution, and promoting social cohesion (Aredo, 2010; Genet, 2021). This shows that traditional financial institutions are not only for money but also for social services, care, and risk sharing. In most of the Ethiopian community norms, doing something only for money is considered bad. Anyone who only focuses on money is considered greedy and inhuman. This might be another reason why people are suspicious of banks because they only focus on money and making profit. For this reason, modern economic institutions can expand their services or engage in humanitarian activities too.

Flexibility and working with vulnerable groups

Research shows that informal economic institutions in Ethiopia are flexible, adaptive, and negotiable (Habtu, 2012). These institutions are established based on well-defined rules and regulations (Hoddinott, Yisehac (2015)). But they are flexible in their service—in providing money for their customers. One of the biggest complaints that the interview participants raised was the rigid system of modern economic institutions in Ethiopia. When it comes to giving money, these institutions have ‘rules and regulations’, which are not compatible with the local community culture or norms and are mostly based on the Western institutional culture. Western institutions are mostly based on mistrust, or at least ‘calculative trust’ (Williamson, 1993). Nevertheless, successful informal institutions can teach a good lesson in terms of this. They are not only flexible in terms of their services but also adaptive and negotiable. Adapt to different places’ cultures and situations. For instance, the way they give money as a form of loan is different from place to place in different parts of Ethiopia. They adapt to the area’s main economic activities, climate, the main product of the area, religion, and even literacy level. Modern economic institutions can study and learn from this to make their services flexible and adaptable depending on the situation in which they are operating.

Habtu (2012) indicated that these informal institutions help mostly the most vulnerable groups of society. They not only focus on the rich or those who have money, like modern institutions, but also on the vulnerable. This not only helps them reach a large number of people, the mass or majority, but also makes them preferable to development actors because they are more accessible than government-affiliated formal institutions (Walo, 2016). This includes a willingness to work with the low-income community and allow them to save money with their capacity. For instance, in Equb, anyone can participate in saving starting from 100 to 10,000 ETB and even as low as 50 ETB or 10 ETB. As a reminder, one informant noted that ‘banks and insurance companies should know that the majority of Ethiopian society is poor.’ Modern economic institutions only focus on the rich. They give special services to the rich.

Working with a vulnerable group of the community also requires an effort to address food insecurity. Informal institutions, such as Edir, Equb, and Debo, are actively participating in food security. Membership in these institutions significantly contributes to food security (Negera et al., 2019). Modern economic institutions such as banks and insurance can play a role in food security by working with poor community members. Especially during the harvest season, they can work with farmers by providing loan to organize their harvest and plan their future savings.

Inclusiveness, ingenuity, and creativity

Data shows that traditional informal institutions in Ethiopia are inclusive, democratic, ingenious, and creative. Wedajo et al. (2019) indicated that these informal institutions are inclusive. Edir is considered to be ‘Ethiopia’s most democratic and egalitarian social organization.’ (Pankhurst and Mariam, 2000). The qualities of inclusiveness and egalitarianism make them owned by the community. This is one of the important qualities that the modern economic institutions in Ethiopia lack. They are established based on the models of Western structure, with no need for or base in the community.

Nevertheless, modern economic institutions can be inclusive, ingenuous, and creative by establishing a community advisory group (CAG). They can include senior community members, elders, heads of community-based organizations (CBO), religious leaders, traditional village leaders, and also former collectors of Equb and Edir to learn from and adapt to traditional economic institutions. This not only helps them to be inclusive and egalitarian, but also to know what the community thinks of them and how to adopt some techniques and strategies to encourage saving and get more trust and customers from the community. They can have regular meetings with these advisory groups to share their progress and get recommendations from them. The advisory group can show them ways to share benefits with the community in a way that benefits the institutions. By narrowing the differences between modern economic institutions and indigenous community-based organizations, the advisors can serve as a bridge between the two.

Most studies also admired the ‘ingenuity and creativity’ of the informal institutions and indicated the cooperatives’ and ‘huge potential for saving mobilization’ (Aredo, 1993; Teshome, 2008). In addition, if banks establish and effectively run community advisory groups, they can help them adopt the ‘ingenuity and creativity’ of the informal indigenous institutions. Banks in Ethiopia are working hard to mobilize savings; nevertheless, none of them have worked with informal saving institutions so far, which is regarded as a ‘huge potential for saving mobilization’. Rather than investing billions in advertising, it is wise to work with informal institutions by establishing advisory groups. Studies show that they have more power to influence community members’ behavior, decisions, attitudes, and practices (Regassa et al., 2013).

These three lessons for modern economic institutions in Ethiopia are interrelated (see Fig. 3). Trust building and reliability depend on flexibility and working with the vulnerable, which also needs inclusiveness and ingenuity. As indicated above, to be acceptable and trusted among the community, they need to be flexible and ready to work with anyone, including the vulnerable and poor groups of the community. To be flexible and ready to work with others, they have to be inclusive and resourceful. They have to establish a community advisory group, start working on their weaknesses, and learn from the indigenous institutions. Nevertheless, recent studies are showing that these indigenous traditional institutions are declining because of ‘modernization’ and urbanization. Yazew and Kassa (2024) revealed the decline of traditional norms amidst urban expansion which presents challenges for modern economic institutions, underscoring the importance of integrating social norms into economic planning. Thus, we need policies that recognize and preserve traditional social norms which are essential for fostering trust in economic institutions and facilitating effective economic governance.

Conclusions and recommendations

Our study demonstrates that SNs play a critical role in shaping trust in financial institutions and influencing economic behaviors in Ethiopia. Quantitative analysis of the 2020 WVS data, corroborated by qualitative insights from KII, reveals that while a significant majority of respondents adhere to traditional norms, a notable minority deviates from these expectations. This divergence is associated with differences in work-related beliefs, saving practices, and institutional trust. Specifically, individuals with strong adherence to traditional SNs tend to favor conventional employment channels, exhibit lower trust in formal institutions, and maintain more negative attitudes toward wealth accumulation. In contrast, those who deviate from these norms demonstrate a more pragmatic approach toward financial decision-making, higher levels of trust in modern institutions, and a greater willingness to invest rather than merely save. However, our findings also indicate that variables such as education, income levels, and access to financial services are interwoven with SNs, highlighting a complex socio-economic matrix that shapes economic outcomes.

In light of these findings, we recommend that modern financial institutions in Ethiopia adopt a community-centered approach to foster trust and enhance financial inclusion. Economic institutions should integrate culturally sensitive strategies that leverage religious networks and expand outreach through civic and professional organizations. Given that 97% of respondents consider God central to their lives, and 78.53% align with confirmatory social norms, faith plays a significant role in shaping economic attitudes. Therefore, institutions must recognize the importance of religious and community-based structures and design strategies that combine both faith-based trust and formal economic systems. We also recommend establishing Community Advisory Groups (CAGs) consisting of local leaders, religious figures, and representatives from Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) like Edir and Equb, to provide feedback for modern EI on financial products and services that reflect local cultural values. It is also important to tailor financial products to demographic variations by offering flexible savings schemes, adaptive credit policies, and targeted financial literacy programs that consider cultural values. Finally, institutions must streamline operations by simplifying loan processes, reducing collateral requirements, and enhancing withdrawal mechanisms, to minimize bureaucratic barriers and improve customer satisfaction. By implementing these strategies, Ethiopia’s financial institutions can bridge the gap between traditional social norms and modern economic practices, fostering inclusive growth and stronger institutional trust.

Data availability

The curated dataset and specific raw data that support the findings of this study is deposited in the academic repository Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/A7BFWU. The KII data is provided within the manuscript and also supplementary information files, separately uploaded as Appendix (APX). All the data used in this study are available in the paper or separately uploaded in Table.

Notes

The curated data used for the study can be found on Harvard Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/A7BFWU.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2012) The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty: Why nations fail. Crown Business, New York

Admassie Y (1999) Institutions, political freedom and development in Ethiopia. Econ Focus 8(6):2006:20-37

Akerlof GA (1980) A theory of social custom, of which unemployment may be one consequence. Q J Econ 94(4):749–775

Alesina A, Giuliano P, Nunn N (2013) On the origins of gender roles: women and the plough. Q J Econ 128(2):469–530

Algan Y, Cahuc P (2010) Inherited trust and growth. Am Econ Rev 100(5):2060–2092

Alpman A (2013) The relevance of social norms for economic efficiency: theory and its empirical test. Centre d’Économie de la Sorbonne Working Paper no. 13038. Université Paris 1

Aredo D (1993) The informal and semi-formal financial sectors in Ethiopia: a study of the iqqub, iddir, and savings and credit co-operatives. AERC Research Paper 21, African Economic Research Consortium

Aredo D (2010) The Iddir: an informal insurance arrangement in Ethiopia. Savings Dev 34:53–72

Awol E (2025) The numbers don’t lie: ethiopia’s gender gap in digital financial services runs deep. In: Shega. Available at: https://shega.co/news/the-numbers-dont-lie-ethiopias-gender-gap-in-digital-financial-services-runs-deep?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Baidoo ST, Akoto L (2019) Does trust in financial institutions drive formal saving? Empirical evidence from Ghana. Int Soc Sci J 69(231):63–78

Banerjee AV, Duflo E (2011) Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. PublicAffairs, New York

Bessir M (2018) Financial inclusion in Ethiopia: 10 takeaways from the latest Findex. In: World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/financial-inclusion-in-ethiopia-10-takeaways-from-findex-2017

Buriak A, Vozňáková I, Sułkowska J et al. (2019) Social trust and institutional (bank) trust: empirical evidence of interaction. Econ Socio 12(4):116–332

Cho S-Y (2021) Social capital and innovation in East Asia. Asian Dev Rev 38(1):207–238

Collins D, Morduch J, Rutherford S, et al. (2009) Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Costenbader E, Cislaghi B, Clark CJ et al. (2019) Social norms measurement: Catching up with programs and moving the field forward. J Adolesc Health 64(4):S4–S6

Crummey D (2000) Land and society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: from the thirteenth to the twentieth century. University of Illinois Press, Illinois

Deflem M (2015) Deviance and social control. In: Goode E (ed) The handbook of deviance. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp 30–44

Demirguc-Kunt A, Klapper L, Singer D, et al. (2018) The Global Findex Database 2017: measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank Publications, Washington, DC

Dequech D (2006) Institutions and norms in institutional economics and sociology. J Econ Issues 40(2):473–481

Dercon S, De Weerdt J, Bold T et al. (2006) Group-based funeral insurance in Ethiopia and Tanzania. World Dev 34(4):685–703

Elster J (2016) Social norms and economic theory. Cult Politics A Read 3(4):363–380

Eriksson L (2015) Social norms theory and development economics. Polic Res Working Pap 7450, World Bank, Washington, DC

Fukuyama F (1996) Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Simon and Schuster, New York

Genet A (2021) Indigenous institutions and their role in socioeconomic affairs management: evidence from indigenous institutions of the Awi people in Ethiopia. Int Soc Sci J 72(243):225-41

Gradstein M, Konrad KA, Kai KA (2006) Institutions and norms in economic development. Mit Press, Cambridge, MA

Gudata ZG (2020) Khat culture and economic wellbeing: Comparison of a chewer and non-chewer families in Harar city. Cogent Soc Sci 6(1):1848501

Habtu K (2012) Classifying informal institutions in Ethiopia. Unpublished Master's Thesis, Wageningen University

Haerpfer C, Inglehart, R, Moreno, A, Welzel, C, Kizilova, K, Diez-Medrano J, M Lagos, P Norris, E Ponarin & B Puranen et al. (eds) (2020) "World values survey: Round seven–country-pooled datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat 7:2021

Hoddinott JY, Yisehac (2015) Ethiopian Rural Household Surveys (ERHS), 1989-2009. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Hoff K, Stiglitz JE (2016) Striving for balance in economics: towards a theory of the social determination of behavior. J Econ Behav Organ 126:25–57

Inglehart R, Baker WE (2000) Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. Am Sociol Rev 19–51

Inglehart R, C Haerpfer, A Moreno, C Welzel, K Kizilova, J Diez-Medrano, M Lagos, P Norris, E Ponarin & B Puranen et al. (eds) (2014) World Values Survey: Round Five—Country-Pooled Datafile Version. JD Systems Institute, Madrid

Jack W and Suri T (2011) Mobile money: the economics of M-PESA. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Jayachandran S (2020) Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Kenea DA, Yemane F, Teshome G (2020) Institutional development In Ethiopia: challenges and policy options. Soc Sci Educ Res Rev 7(2):69–88

Knack S, Keefer P (1997) Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q J Econ 112(4):1251–1288

Lajčiak M (2017) East Asian economies and their philosophy behind success: manifestation of social constructs in economic policies. J Int Stud 10(1):180–192. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-1/13

Lawrence EH, Samuel PH (ed) (2000) Culture matters: How values shape human progress. Basic Books, New York

Mariam DH (2003) Indigenous social insurance as an alternative financing mechanism for health care in Ethiopia (the case of eders). Soc Sci Med 56(8):1719–1726

Meek WR, Pacheco DF, York JG (2010) The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. J Bus Ventur 25(5):493–509

Meijerink G, Bulte E, Alemu D (2014) The interaction of formal and informal institutions in development: the Ethiopian commodity exchange and social capital in Sesame Markets. Food Policy, 49(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.05.015

Mogues T (2006) Shocks, livestock asset dymanics and social capital in Ethiopia. IFPRI, Washington, DC

Murphy JT (2006) Building trust in economic space. Prog Hum Geogr 30(4):427–450

Negera CU, Bekele AE, Wondimagegnehu BA (2019) The role of informal local institutions in food security of rural households in southwest Ethiopia. Int J Community Soc Dev 1(2):124–144

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nunn N, Wantchekon L (2011) The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. Am Econ Rev 101(7):3221–3252

Oniki S, Berhe M, Negash T (2020) Role of social norms in natural resource management: the case of the communal land distribution program in northern Ethiopia. Land 9(2):35

Pankhurst A, Mariam DH (2000) The” Iddir” in Ethiopia: Historical development, social function, and potential role in HIV/AIDS prevention and control. Northeast Afr Stud 7:35–57

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and schuster, New York

Regassa N, Mengistu E, Yusufe A (2013) Situational analysis of indigenous social institutions and their role in rural livelihoods: the case of selected food insecure lowland areas of Southern Ethiopia. (DCG) Report No. 73, Oslo, Norway

Stratton LS, Datta Gupta N (2021) Institutions, social norms, and bargaining power: an analysis of individual leisure time in couple households. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1293545

Teshome A, de Graaff J, Kessler A (2016) Investments in land management in the north-western highlands of Ethiopia: the role of social capital. Land Use Policy 57:215–228

Teshome T (2008) Role and potential of ‘Iqqub’in Ethiopia a project paper submitted to the school of graduate studies of Addis Ababa University in partial fulfillments of the requirements for the degree of master of science in accounting and finance. Master Degree, University of Addis Ababa

Walo MT (2016) Local institutions and local economic development in Guto Gidda district, Oromia region, Ethiopia. J Poverty Alleviation Int Dev 7:122–158

Weber M (1930) The protestant ethic and the” Spirit” of capitalism. Charles Scribner’s, New York

Wedajo DY, Belissa TK, Jilito MF (2019) Harnessing indigenous social institutions for technology adoption: ‘Afoosha’society of Ethiopia. Dev Stud Res 6(1):152–162

Williamson OE (1993) Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization. J law Econ 36(1, Part 2):453–486

World Bank Group (2020) Ethiopia economic update: navigating a challenging climate. World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Yayeh FA, Demissie WM (2025) Social capital and saving behavior in ethiopia: evidence from the Amhara National Regional State. Innov Econ Front 28(1):01–13

Yazew BT, Kassa G (2024) Social structure and clan group networks of Afar pastorals along the Lower Awash Valley. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–20

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Policy Study Institute of Ethiopia for funding this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zerihun Girma Gudeta: Conceived the research idea and performed the majority of the work, including data analysis, drafting, compiling, and rewriting the manuscript to meet journal requirements. Led the editing and review processes.Girma Teshome: Reviewed and provided editorial feedback on the manuscript. Daniel Amante: Assisted in data collection, summarized results, and contributed to manuscript editing. Lalise Kumera: Participated in data collection, result summarization, and manuscript editing.Yohanes Abraham: Contributed to data collection and result summarization.Alemahu Tekeste: Assisted in data collection and result summarization.Gezehagn Mengesha: Analyzed data in STATA, producing tables and graphs for the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Ethical approval was granted by the Policy Study Institute (PSI) of Ethiopia on September 2022. The letter from the institute (Ref. No. PSI/1399/25) confirms that all research procedures in this study adhered to all relevant ethical guidelines and regulations to ensure participant safety, confidentiality, and data integrity.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained orally from all participants between November 2022 and February 2023, prior to their involvement in the study. The consent procedure was conducted by trained data collectors who explained the purpose, objectives, and procedures of the study in the participants’ preferred local language. Participants were informed about their rights, including voluntary participation, the right to decline or withdraw at any time without consequences, and assurances of confidentiality and anonymity. Participants gave oral consent to: • Participate voluntarily in the study activities as outlined, • Allow the use of their anonymized data for analysis, publication, and future research related to the study, • Permit the sharing of findings with relevant stakeholders and the academic community. All data were anonymized and securely handled to maintain participant confidentiality throughout the research process.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) usage

We have used Open Paperpal on 5/4/2025 for language polishing and editing.

Limitation of the study

This study examines the role of SNs in shaping EIs in Ethiopia, focusing on banks and insurance as modern EIs and Edir and Equb as SN-based traditional EIs, using WVS data, interviews, and secondary sources to explore their impact on household well-being and EI development. However, it has limitations that may affect its findings, particularly regarding confounding variables. While we recognize the importance of factors like education, income levels, and access to financial services, these were not fully explored beyond noting no major differences between confirmatory and non-confirmatory groups, potentially missing their broader influence on economic outcomes. Similarly, other variables such as poverty, conflict, and instability, which could significantly affect EIs, were excluded due to the study’s narrow focus on SNs. Additional limitations include challenges in measuring multifaceted SNs, potential biases from self-reported data, difficulties in establishing causality between SNs and economic behavior. These constraints suggest that while SNs are critical, unexamined confounding factors may also shape EI effectiveness, warranting further research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gudeta, Z.G., Teshome, G., Amente Kenea, D. et al. The role of social norms in shaping trust and economic behavior in the Ethiopian financial institutions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1473 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05299-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05299-5