Abstract

As environmental awareness grows, consumer responses to corporate sustainability claims vary widely, with some embracing green products and others remaining skeptical. Existing research primarily examines pre-purchase decision-making, leaving a gap in understanding how post-purchase revelations influence consumer attitudes. Drawing on behavioral reasoning theory, this study explores how post-purchase disclosure of core (e.g., eco-friendly fabrics) and peripheral (e.g., recycled packaging) green attributes influences consumer perceptions. Compared to peripheral attributes, core attributes are more likely to trigger perception that conflicts with pre-purchase beliefs. Through a scenario-based experimental design focused on green apparel, we find that post-purchase exposure to credible environmental information can mitigate initial skepticism, improving attitudes and encouraging brand advocacy. These effects depend on the centrality of the green attributes and are moderated by self-affirmation. Core green attributes may enhance risk perception, while self-affirmation helps consumers reconcile doubts, maintaining brand advocacy. These findings contribute to theoretical understandings of green skepticism, demonstrating its malleability, and offer practical insights for marketers. By strategically communicating green attributes post-purchase, firms can encourage hesitant buyers to support sustainability efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, growing environmental awareness has reshaped consumer behavior, yet responses to corporate sustainability efforts vary widely. While some consumers embrace green products, others remain skeptical, questioning the authenticity and impact of environmental claims (Elhoushy and Jang, 2023). Companies respond differently to this tension. Some emphasize their sustainability credentials prominently, whereas others minimize such messaging to avoid the perception that environmental improvements come at the expense of product quality (Fella and Bausa, 2024). This has led to the emergence of two contrasting communication strategies: greenwashing and greenhushing (Policarpo et al., 2023; Tao, 2024).

Greenwashing refers to deceptive marketing practices where companies exaggerate or falsify their environmental claims to mislead consumers (Santos et al., 2024). Over time, greenwashing undermines the credibility of sustainability claims, increasing consumer skepticism toward corporate environmental initiatives (Free et al., 2024). In contrast, greenwashing occurs when firms intentionally understate their eco-friendly practices for fear that making such claims could trigger consumer skepticism or negative reactions (Khan et al., 2023). Greenhushing tends to be more prevalent in culturally conservative countries, where traditional cultural norms may foster resistance to sustainability changes, leading companies to minimize their green marketing efforts (Tao, 2024). While much of the existing literature has focused on consumer reactions to greenwashing (Rossi et al., 2024), the opposite scenario remains underexplored: how do consumers respond when they unexpectedly discover a product’s green attributes after making a purchase?

In the fashion industry, where product value is influenced by factors such as sustainability, style, brand identity, and functionality (Bai et al., 2024), companies may not intentionally conceal sustainability messages but may prioritize marketing style and brand over sustainability. Additionally, marketers tend to avoid promoting green practices to some consumers who associate green products with higher costs and reduced functionality (Riva et al., 2024). As a result, consumers may discover environmental information through clothing labels and advertisements after making a purchase. The impact of such post-purchase exposure to sustainability information on consumer attitudes and behavior is a key concern for us.

This research addresses this gap by focusing on how new details about a product’s green attributes learned after purchase can influence consumer evaluations. To deepen these insights, we incorporate the concept of green attribute centrality, distinguishing between core attributes, such as eco-friendly fabrics integral to functionality, and peripheral attributes, like recycled packaging that complements the product’s value. This distinction offers a fresh perspective on how the nature of green features affects perceived benefit and risk in a post-purchase context. Core attributes, being central to the product’s functionality, tend to enhance perceived benefits but may also heighten perceived risk due to concerns about performance trade-offs.

Specifically, this research seeks to answer two key questions: (1) How does post-purchase information about green attributes affect consumer attitudes toward green products? (2) How does the centrality of green attributes moderate the relationship between green skepticism and perceived benefit or risk? By addressing these questions, this study aims to shed light on the mechanisms that influence consumer attitudes, highlighting the potential for brands to engage even skeptical consumers and foster more positive brand evaluations.

The contributions of this study are twofold. First, we enrich the theoretical understanding of green skepticism by showing that it is not fixed; rather, it can be mitigated through thoughtfully presented, post-purchase environmental information. Second, our findings provide practical guidance for marketers. We suggest that a nuanced presentation of green attributes, particularly those integral to a product’s core function, can enhance consumer attitudes and foster brand advocacy, even among consumers who initially doubt sustainability claims.

Theory and concepts

Post-purchase cognitive biases

Research indicates that cognitive biases, particularly cognitive dissonance, significantly influence negative perceptions of products. This influence can lead to emotions, such as anger, regret, and guilt, as well as to product returns (Fernandez-Lores et al., 2024). Because these biases are typically driven by information asymmetry, companies employ various strategies to mitigate them. These strategies include providing detailed product descriptions, offering quality guarantees, and encouraging product reviews (Barta et al., 2023; Philp and Nepomuceno, 2024).

However, complete elimination of information asymmetry is unattainable. On one hand, consumers may discover previously unnoticed product information or seek additional details during usage to validate their choices (Pizzutti et al., 2022). This can lead to a mismatch between expectations and consumption experiences, resulting in cognitive dissonance, particularly in cases of impulse purchases (Zhao et al., 2023). On the other hand, firms sometimes use information bias to create positive surprises, such as offering gifts or product upgrades, which can lead to positive cognitive dissonance (Sun et al., 2020). Consequently, consumers may engage in positive word-of-mouth or make repeat purchases.

In the realm of green consumption, firms’ environmental initiatives do not uniformly promote green consumption; rather, they may inadvertently foster green resistance among consumers (Sharma et al., 2023). Concerned about potential consumer skepticism, quality concerns, and perceptions of product novelty arising from green advertisements, some enterprises choose not to actively highlight environmental attributes during sales transactions (Acuti et al., 2022). This introduces a unique potential for cognitive bias in the context of green consumption: consumers may only become aware of a product’s environmental properties after purchase. This situation has both advantages and disadvantages. Consumers may develop new concerns upon learning about the product’s environmental attributes, or they may come to appreciate the sustainability features that initially seemed uncertain. For example, research in the new energy sector shows that lower energy bills increase consumers’ awareness of the benefits of green appliances (Skackauskiene and Vilkaite-Vaitone, 2023). These findings highlight the need for further exploration in this area.

Behavioral reasoning theory

Behavioral Reasoning Theory (BRT), developed by (Westaby, 2005), provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the cognitive processes that underlie behavioral intentions. BRT posits that individuals’ behaviors are shaped by a complex interplay between five key constructs: values, reasons for the behavior, reasons against the behavior, attitudes, and behavioral intentions (Westaby, 2005). Values serve as the foundational cognitive elements, guiding individuals’ perceptions and influencing the reasons they generate for or against a particular behavior (Claudy et al., 2015).

Reasons are categorized into two broad types: reasons for and reasons against a behavior (Qian et al., 2023). Reasons for the behavior serve as motivators, promoting the desired behavior, while reasons against act as barriers or demotivators, presenting obstacles to action (Westaby, 2005). This dual focus allows BRT to capture the complexity of decision-making, where individuals may simultaneously consider both positive and negative factors, then form the final attitude and behavioral intention (Acikgoz et al., 2023).

The theory’s adaptability makes it applicable across various contexts, including resistance to innovation, technology adoption, implementation barriers, and consumer behavior (Acikgoz et al., 2023; Claudy et al., 2015; Jan et al., 2023). Its unique structure, integrating both motivators and demotivators, provides a nuanced understanding of decision-making processes, particularly within sustainability-related research domains (Sreen et al., 2021; Habib et al., 2025). Especially, BRT has been employed to explore decision-making in areas, such as e-waste recycling and renewable energy adoption, offering valuable insights into the cognitive mechanisms that drive sustainable behavior (Ünal et al., 2024).

Building on these insights, BRT provides a robust framework for understanding how cognitive processes influence consumer behavior in the context of green consumption. In this study, we apply it to explore how skepticism shapes consumer attitudes toward green products by considering both supporting and opposing factors.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Personal value, green attitude, and advocacy in consumption

The value-belief-norm framework posits that consumer values and beliefs exert a significant influence on attitudes toward green products (Lima et al., 2024). Sokolova et al. (2023) underscore the impact of beliefs on environmental judgments and consumer preferences, illustrating how deeply ingrained beliefs, such as “paper good, plastic bad,” significantly shape perceptions of environmental friendliness. Additionally, aspects of personal values, especially altruism and biosphere values, have been identified as promoters of consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward green products (Bhardwaj et al., 2023). Despite prevalent skepticism, pro-green benefits bolster confidence in the efficacy of green products (Lima et al., 2024). Furthermore, Shang et al. (2023) underscore the influence of personal environmental beliefs on attitudes toward green technology products, indicating a direct link between sustainability perceptions and purchase intentions. In this study, we are particularly concerned about green skepticism, which is defined as a consumer value orientation characterized by doubts about the authenticity or efficacy of environmental claims (Lim and Lee, 2023). Consumer skepticism toward green products, fueled by concerns about greenwashing, can lead to a critical and hesitant attitude (Ünal et al., 2024). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Consumers’ green skepticism negatively influences their attitude toward green products.

Furthermore, consumers’ attitudes toward products significantly influence their behavior toward both the product and the brand (Rizomyliotis et al., 2021). Brand advocacy, defined as consumers’ voluntary promotion of a brand through recommendations, defense, or positive storytelling, is a key behavioral outcome of product attitudes (Ahmad et al., 2024). Positive attitudes toward green products enhance brand advocacy by narrowing the attitude-behavior gap (Policarpo et al., 2023). When consumers perceive a product as valuable, they are more likely to engage in advocacy behaviors, such as recommending the brand or making repeat purchases (Sadiq et al., 2023). This is consistent with findings that emotional factors like satisfaction and trust influence consumers’ intentions to repurchase or revisit a brand (Elhoushy and Jang, 2023). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: A positive attitude toward green products encourages consumers’ brand advocacy.

Reason for and against as mediators

According to cognitive dissonance theory, exposure to new information can generate dissonance. In this study, when initially skeptical consumers encounter green information, they may experience discomfort due to doubts about the authenticity of environmental claims (Steenis et al., 2023) or from disruptions to established consumption habits by novel information (Acikgoz et al., 2023). The resolution of this dissonance depends on consumers’ reassessment of the product (Fernandez-Lores et al., 2024): if they come to believe that their choices effectively contribute to environmental protection, they are more likely to accept the new information; otherwise, unresolved dissonance may heighten perceived risks and dampen advocacy intentions.

Building on this foundation, BRT further explains how both supporting and opposing factors influence consumer attitudes post-purchase. Supporting factors are often related to the perceived added benefits of the goods (Jan et al., 2023). In the green consumption scenario, green benefits refer to the perceived advantages of a product in conserving resources, reducing waste, and minimizing pollution (De Silva et al., 2021). Consumers who are naturally inclined toward green skepticism tend to question and undervalue the environmental attributes of products, resulting in a lack of trust in green labels (Riva et al., 2024). However, when consumers discover positive green information post-purchase, they may experience a sense of having “accidentally done a good deed.” This perception fosters a sense of social responsibility and contribution to environmental protection, which can partially counterbalance their initial skepticism and help them maintain a positive impression of the product (Tezer and Bodur, 2020).

Furthermore, using environmentally friendly products can enhance the consumption experience, strengthen environmental self-identity, and generate spillover effects (Stockheim et al., 2024). Perceived green benefits amplify advocacy by fostering emotional connections with the brand (Elhoushy and Jang, 2023). While consumers who consciously choose green products often report more positive experiences, those who adopt green products passively may develop a willingness to advocate for the brand as a way to reinforce their identity as responsible consumers (Tezer and Bodur, 2020).

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3a: Consumers’ green skepticism negatively influences their perceived green benefits.

H4a: Consumers’ perceived green benefits positively influence their attitude toward green products.

H5a: Consumers’ perceived green benefits positively influence their brand advocacy.

In many consumption scenarios, consumer skepticism significantly correlates with negative attitudes toward products and heightened risk perception (Steenis et al., 2023). In this study, the perceived risk primarily refers to functional risk, which concerns a product’s ability to perform as expected and deliver the promised benefits (De Silva et al., 2021). Consumers may perceive green products as an emerging category, to be risky, potentially harmful to health, or falling short of delivering their promised environmental benefits (Acuti et al., 2022; Balassa et al., 2024). This concern is particularly acute in areas integral to daily life, such as food and personal apparel, where consumers are highly sensitive to the potential risks associated with green products (Alyahya et al., 2023).

Innovation Resistance Theory views perceived risk as both a precursor to initial rejection and a barrier to continued engagement with green products. According to this theory, consumers’ resistance to green products stems from perceived risks, such as functional uncertainty (e.g., doubts about durability) and social stigma (e.g., skepticism toward eco-labels). These factors heighten their reluctance to adopt unfamiliar innovations (Chen et al., 2022). Post-purchase, unresolved concerns about product performance or environmental impact further erode trust and deter brand advocacy (Guan et al., 2024; Fernandez-Lores et al., 2024).

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3b: Consumers’ green skepticism positively influences their perceived risk.

H4b: Consumers’ perceived risk negatively influences their attitude toward green products.

H5b: Consumers’ perceived risk negatively influences their brand advocacy.

Green Centrality as moderator

Centrality of green attributes refers to the extent to which environmental attributes are incorporated into the core functionality of a product (Gershoff and Frels, 2015). Central green attributes, intrinsic to a product’s primary utility, may include environmentally friendly production processes or the use of sustainable materials in the product’s main structure. In contrast, peripheral green attributes, such as eco-friendly packaging, contribute to the product’s overall environmental impact without directly affecting its primary utility (Steenis et al., 2023).

Extensive research has examined the effect of integrating green attributes into the core functionality of products on consumer perceptions. When these attributes are central, they are perceived as integral to the product’s design and functionality, directly influencing its performance and environmental impact (Tian et al., 2022). This centrality often elevates the product’s perceived green benefits, as consumers recognize these attributes as essential rather than supplementary components (Gong et al., 2022).

However, enhancing perceived green benefits can complexly impact perceived risk. Central green attributes, while generally enhancing a product’s green identity, can also introduce uncertainties concerning the product’s efficacy and safety. For example, products that come into direct contact with the body, such as clothing, and incorporate green technologies or materials, might be perceived as risky or potentially unhygienic due to unfamiliarity with the long-term effects or performance of these materials under regular use conditions (Acuti et al., 2022). Moreover, the stereotype of “ethical = less strong” significantly influences consumer evaluations of products with prominent green features. Concerns that sustainable products may compromise other critical attributes, such as durability, functionality, and overall quality, frequently elevate perceived risk. This perception is more pronounced with central green attributes because their significance to the product’s core function makes any potential deficiencies more impactful (Rausch et al., 2021). In the case of peripheral green attributes, while consumers may suspect that these features inflate the green benefits of a product, they are less likely to question its functional value or reject the product outright (Steenis et al., 2023).

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6a: High centrality of green attributes enhances the impact of green skepticism on perceived green benefits.

H6b: High centrality of green attributes enhances the impact of green skepticism on perceived risk.

Self-affirmation as moderators

Self-affirmation theory posits that individuals are motivated to maintain a global sense of self-integrity, which includes a perception of oneself as good, moral, and adequate within the norms of their social context (Steele and Liu, 1983). When this self-image is threatened, individuals engage in various cognitive strategies and behaviors aimed at restoring their self-worth. For example, experiencing a dip in confidence or feeling morally compromised may lead individuals to select products or engage in actions that help reaffirm their desired self-image, such as opting for products with intellectual or ethical qualities (Graham-Rowe et al., 2019).

Building on the foundational concepts of self-affirmation theory, prior research indicates that product choices are not merely reflections of consumer preferences but also serve a self-restorative function. Trudel et al. (2020) have shown that consumers under a self-threat are more likely to choose products with ethical attributes, even when competing options are superior in terms of quality or quantity. This preference is primarily driven by the need to restore self-esteem, which is bolstered when the chosen product aligns with the individual’s moral or ethical values.

Research has delved into how self-affirmation helps bridge the attitude-behavior gap, particularly when consumers encounter conflicting information before purchasing. Exposed to such contradictions, consumers interpret details in ways that align with their beliefs, maintaining a favorable product view, demonstrating self-affirmation’s influence on perception (Whang et al., 2024). Self-affirmation also plays a pivotal role when consumers initially resist new products. It boosts self-confidence, increasing openness to novel products, highlighting its role in adapting consumer attitudes toward market innovations (Emonds et al., 2023).

In the post-purchase phase, self-affirmation remains vital. For example, a consumer with strong self-affirmation tendencies might find a product less effective than expected, but is unlikely to view this negatively. Instead, they focus on product aspects that align with their initial purchase reasons, allowing them to reinterpret negative attributes in ways that uphold their self-integrity (Girardin et al., 2021). This cognitive adjustment not only helps them accept their choice but also increases the likelihood of future repurchases.

Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7: High self-affirmation enhances the impact of product attitude on brand advocacy.

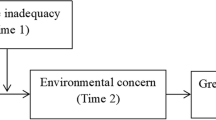

In conclusion, the theoretical framework proposed in this research is illustrated in Fig. 1, where the ‘+‘ and ‘−‘ signs denote the hypothesized positive and negative effects, respectively.

Methodology

Experimental design

This study uses a scenario-based experiment to examine how post-purchase green information influences consumer cognition and behavior, specifically in the context of green apparel. The apparel industry, with its significant environmental impact, provides a relevant setting for exploring consumer responses to sustainability initiatives. Green apparel is defined by low-pollution materials, eco-friendly production, recyclability, and durable design (Bai et al., 2024). Its everyday relevance and subtle green marketing (e.g., eco-certifications or practices displayed on hangtags) make it an ideal subject for studying the effects of post-purchase information (Khan et al., 2023).

To establish a post-purchase context, the survey begins with a scenario-based prompt. The scenario is framed as follows: “You have just received a clothing item purchased online. As you open the package and remove the price tag, you notice an additional hangtag attached to the garment. This tag provides information that you did not notice at the time of purchase, which reads as follows”.

The information on the hangtag is randomly presented in two versions: one emphasizing core attributes and the other focusing on peripheral attributes (Gershoff and Frels, 2015).

The first version emphasizes the central attribute: “The fabric of this clothing is crafted from polyester yarn produced through the regeneration of existing industrial materials. This process reduces energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. It breathes new life into resources that would otherwise remain unused, all without compromising the garment’s quality and design integrity”.

The second version focuses on the peripheral attribute: “The brand advocates for plastic-free packaging. The tags, packaging boxes, and stuffing of this garment are all made from recycled paper products. Adhering to the principle of reduction, the design of the packaging minimizes both volume and weight, which reduces energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions while ensuring the clothing remains well-protected.”

To reinforce the post-purchase mindset, the questionnaire included the following instruction: “Please respond to the following questions based on the given scenario, where you became aware of the apparel’s ‘green claim’’ after making the purchase”.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two stimulus conditions and then asked to complete a manipulation check to assess the effectiveness of the stimuli. The manipulation check consisted of two items, measured using seven-point Likert-type scales: “How important is the fabric (packaging) to the performance and functionality of this clothing?” and “To what extent does the fabric (packaging) constitute a defining part of green clothing?”

Measurements

We adopt and adapt various established scales to measure key constructs (see Appendix). Specifically, we use the scale from Riva et al. (2024) to measure consumers’ green skepticism, the scale from Bergner et al. (2023) to measure brand advocacy, the scale from Peterson et al. (2022) to measure self-affirmation, the scale from Tonder et al. (2023) to measure attitudes toward products, and the scale from De Silva et al. (2021) to measure perceptions of green benefits and risks. All items are measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Additionally, we include three control variables in the questionnaire: gender, age, and education level.

Pretest

A pretest was conducted with 70 undergraduate students majoring in business administration at a university. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two stimuli. The manipulation check was first administered, and the results of a one-way ANOVA indicated that the average response to the first question differed significantly between the central and peripheral conditions (Mcentral = 4.74, Mperipheral = 3.7, p < 0.001). Similarly, the average response to the second question also showed a significant difference between the central and peripheral conditions (Mcentral = 4.93, Mperipheral = 3.58, p < 0.001). These results confirm that respondents understood the scenario as intended.

Secondly, a reliability and validity test on the scales was conducted. Both scales demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity, confirming their appropriateness for analysis.

Empirical analysis

Data collection and description

Data collection was conducted online through the commercial survey platform Credamo (www.credamo.com), with the research team paying 4 RMB per respondent. The platform provided 1000 valid and complete responses for analysis. Table 1 presents the demographic statistics of the respondents. The sample consists of 1000 respondents with a balanced gender distribution, predominantly younger consumers (aged 20–34), and most participants have a bachelor’s degree or higher. The sample is geographically and culturally homogeneous, as all participants are from China.

To ensure the robustness of our study, we conducted a statistical power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.6 (Faul et al., 2009). We specified a two-group, one-way ANOVA with an effect size f = 0.4 (large effect), a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a total sample size of 1000 participants. The analysis revealed that the achieved statistical power was 1.0, indicating a very high probability (100%) of detecting a significant effect if one truly exists.

The manipulation validity was reassessed prior to data analysis, revealing significant differences in participants’ responses between conditions. For the first question, mean responses were Mcentral = 4.69 and Mperipheral = 3.56 (F = 210.52, p < 0.001), while for the second question, mean responses were Mcentral = 4.88 and Mperipheral = 3.83 (F = 203.92, p < 0.001). These findings confirm that the manipulation successfully differentiated between central and peripheral attributes, supporting the validity of the experimental setup.

Measurement reliability and validity

SPSS 26.0 and SmartPLS 4.1 were used to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement scales. The results, as shown in Table 2, indicate that the reliability of the measurements is satisfactory, with both Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2019). Convergent validity was also confirmed, as all factor loadings exceeded 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.5, further supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

Discriminant validity of the measurements was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). This criterion requires that the square root of the AVE for each construct be greater than the correlation coefficients between that construct and any other. As shown in Table 3, the results meet this requirement, confirming the discriminant validity of the measurements.

Additionally, Harmon’s single-factor test was conducted to check for potential common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The analysis revealed that four factors together accounted for 72.48% of the total variance, with the first factor explaining only 37.28%. This indicates that common method bias is unlikely to be a significant issue in this study.

Hypothesis test

The PLS-SEM method was employed to test the hypotheses in the conceptual research model. In the first step, since the centrality of green attributes serves as a grouping variable reflecting the predefined scenario, Hypothesis H6, which addresses the moderating effect of green centrality, was not included in the base model.

The path coefficients of the structural model (see Table 4) indicate that only Hypothesis H5a was not supported, suggesting that perceived green benefits may not have a significant impact on consumers’ brand advocacy. The findings for the remaining hypotheses align with expectations. Furthermore, no significant effects of the anticipated control variables on consumers’ brand advocacy were identified.

Building on the existing conclusions, Hypothesis H6 was tested using two methods to assess the moderating effect of green attribute centrality.

In the first approach, green centrality was treated as an ordinal variable (peripheral condition = 1, central condition = 2) and added to the base model as a moderating factor. The results, presented in Table 5, column “Model 1,” indicate that Hypothesis H5a remains unsupported even with the inclusion of the moderating variable. However, the analysis supports Hypothesis H6b, suggesting that higher green centrality enhances the impact of green skepticism on perceived risk.

The second approach involved dividing the sample into two groups: Group 1 representing the peripheral condition, and Group 2 representing the central condition. A bootstrap multigroup analysis was performed to compare the path coefficients of the base model between the two groups, assessing the existence of a moderating effect. The results, shown in Table 5, column “Model 2,” reveal differences in the path coefficients for H3b and H4a. These findings suggest that high green centrality positively influences the relationship between green skepticism and perceived risk. Therefore, H6b was supported, while H6a was not supported in both models.

Additionally, the result of Model 2 suggests that green centrality negatively affects the relationship between perceived green benefits and product attitude. Specifically, high green attribute centrality disrupts the positive correlation between perceived green benefits and product attitude, resulting in a sustained correlation but with a diminished effect.

General discussion

Results summary

This study uniquely investigates the context of post-purchase information acquisition concerning the green attributes of products, highlighting how this specific scenario influences consumer behavior and attitudes. The findings confirm that while green skepticism may initially deter consumers, acquiring information about a product’s green features after purchase can foster acceptance and support for the brand.

Overall, the results support the idea that green skepticism encourages consumers to recognize the benefits and risks of products, which in turn shapes their product attitudes. These attitudes, along with risk perception, ultimately influence their willingness to advocate for the brand. Building on this foundation, the study reveals that increased green centrality amplifies the influence of consumers’ green skepticism on their perceived risk. Furthermore, confident consumers are likely to set aside their skepticism when they become aware of a brand’s sustainable practices, allowing them to continue supporting the brand.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the fields of green marketing and sustainability communication.

First, this study makes theoretical contributions to BRT by applying its core constructs to the post-purchase context of green consumption. Except for considering how conflicting motivations and cognitive processes drive attitudes (Westaby, 2005; Claudy et al., 2015), this study explores the probable shift in consumer attitudes and behaviors. Furthermore, the study explores the influencing factors within variable correlations, including the moderating effects of external information attributes and individual self-affirmation, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the theory. While this study focuses on post-purchase attitudes, examining the long-term effects on consumer behavior will provide valuable insights into how these attitudes evolve, making consumers more receptive to green products.

Second, this study extends the literature on green skepticism by revealing how post-purchase communication strategies shape its dynamics. Green skepticism, as a response to greenwashing risks (Santos et al., 2024), could be mitigated after transactions. For moderately skeptical consumers (Park et al., 2014), cognitive dissonance arises from conflicting evaluations of green attributes, which drives them to reinterpret post-purchase information to align with their self-concept. While much of the previous research has focused on pre-purchase decision-making processes (Lim and Lee, 2023), our findings demonstrate how post-purchase disclosures of green attributes (e.g., putting a notice about using eco-friendly dyes or recyclable packaging on the hangtag) can recalibrate consumer evaluations and influence brand advocacy. By demonstrating how consumer perceptions evolve, this work offers a novel perspective on mitigating green skepticism in sustainable marketing.

Third, the introduction of green attribute centrality as a moderating factor contributes to the understanding of how core and peripheral green attributes affect perceived benefit and risk. Core attributes (e.g., eco-materials) increase perceived risk because consumers associate sustainability with functional compromises (e.g., “organic cotton may wear out faster”), challenging assumptions that central green features only enhance benefits (Gong et al., 2022). This paradox, where stronger sustainability features may backfire, reflects consumers’ implicit belief that ethical attributes signal trade-offs in reliability (Rausch et al., 2021). Conversely, peripheral attributes (e.g., recyclable packaging) avoid such trade-offs, making them safer for skeptical consumers.

Finally, the study adds to the growing body of research on self-affirmation theory in consumer behavior, demonstrating that self-affirmation plays a significant role in helping consumers overcome skepticism toward green products. This finding aligns with previous studies that emphasize the transformative power of self-affirmation in altering consumer attitudes (Trudel et al., 2020). Confident consumers, who already trust their decision-making abilities, are more likely to embrace post-purchase information about a product’s sustainable features. This process aligns with cognitive dissonance theory, where confidence helps individuals resolve doubts by reconciling post-purchase green information with their self-affirmation (e.g., I chose this product, so I believe my choice).

Managerial implications

The findings of this study present several important implications for marketers and managers in the green product sector.

First, the study suggests that strategic post-purchase communication of green attributes can play a crucial role in fostering advocacy. Managers could adopt a phased communication strategy that aligns with consumer decision-making stages. Core green attributes (e.g., eco-friendly materials) should be emphasized pre-purchase to attract sustainability-conscious consumers. For example, Patagonia’s “Fair Trade Certified” materials highlight the company’s environmental commitments, positively impacting its sales. Peripheral attributes can be highlighted post-purchase to reassure skeptics by showcasing low-risk environmental benefits. For example, the presence of an FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) label on clothing tags and packaging indicates responsible sourcing of paper products and underscores the brand’s commitment to sustainability without interfering with pre-purchase decision-making. Besides, green attribute communication can vary by market context. In developed markets, where consumers are familiar with sustainability, the focus may be on long-term benefits of core green attributes, such as eco-friendly materials or processes. In emerging markets, marketers could emphasize immediate functional benefits, like durability or cost-efficiency.

Second, the study highlights the role of self-affirmation in moderating consumer responses to green products. Marketers can leverage this by developing messaging strategies that reinforce consumers’ sense of ethical responsibility and self-affirmation. For example, Starbucks’ coffee grounds initiative enhances self-affirmation in two ways. Starbucks leverages its corporate credibility to reinforce trust in its green claims. The coffee grounds cup, made with 30% recycled coffee grounds (Starbucks, 2020), capitalizes on the brand’s reputation for quality, prompting consumers to think, “If Starbucks endorses this, it must be credible.” Moreover, Starbucks engages consumers in actionable sustainability practices by offering free, processed coffee grounds for household use. This fosters a sense of personal agency, as consumers feel they are contributing to environmental protection. These efforts not only reinforce consumers’ positive self-concept but also deepen their emotional connection to the brand, driving advocacy.

Finally, negativity bias must be considered when designing communication strategies. Since negative perceptions about green products can disproportionately affect consumer attitudes, brands could ensure post-purchase communication clearly articulate both the consumer and environmental benefits. For example, Lush Cosmetics explains that the minimal use of preservatives in its products is due to their self-preserving properties, achieved through natural ingredients that benefit both the environment and consumer health. Transparent messaging not only prevents consumers from feeling misled but also better aligns green initiatives with their priorities.

Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, the scenario-based experimental method and limited sample may not fully capture the complexities of consumer decision-making. The reliance on self-reported data could introduce social desirability bias, where respondents may answer in ways they think are socially acceptable rather than truthfully. As the study focuses on Chinese consumers, the findings may be limited in their applicability to other cultural or geographical contexts. Future research could incorporate mixed methods, including behavioral data or third-party reports across different cultures, to provide a more objective and accurate assessment of consumer attitudes.

Second, the study focused exclusively on a single category of green clothing products. This narrow scope may limit the applicability of the findings to other industries. Further research should explore these dynamics across various contexts and product categories to enhance the understanding of green consumer behavior more broadly. By examining different sectors, researchers can identify whether the observed patterns hold true across diverse markets, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of consumer attitudes toward green products.

Finally, future studies could incorporate additional important factors, such as consumers’ green knowledge, environmental involvement, and regulatory focus, and assess their impact on consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable products. Additionally, exploring the moderating effects of these variables on green skepticism and brand advocacy could provide deeper insights into the complexities of consumer behavior in green consumption.

Data Availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Acikgoz F, Perez-Vega R, Okumus F, Stylos N (2023) Consumer engagement with AI-powered voice assistants: a behavioral reasoning perspective. Psychol Mark 40(11):2226–2243

Acuti D, Pizzetti M, Dolnicar S (2022) When sustainability backfires: a review on the unintended negative side-effects of product and service sustainability on consumer behavior. Psychol Mark 39(10):1933–1945

Ahmad N, Ahmad A, Siddique I (2024) Beyond self-interest: how altruistic values and human emotions drive brand advocacy in hospitality consumers through corporate social responsibility. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 31(3):2439–2453

Alyahya, M, Agag, G, Aliedan, M, Abdelmoety, ZH, & Daher, MM (2023). A sustainable step forward: understanding factors affecting customers’ behaviour to purchase remanufactured products. J Retail Consum Serv 70:103172

Bai, Y, Chen, JP, & Geng, LA (2024). Beyond buying less: a functional matching perspective on sustainable fashion product purchasing. J Environ Psychol 95:102283

Balassa, BE, Nagy, NG, & Gyurián, N (2024). Perception and social acceptance of 5G technology for sustainability development. J Clean Prod 467:142964

Barta, S, Gurrea, R, & Flavián, C (2023). Using augmented reality to reduce cognitive dissonance and increase purchase intention. Comput Hum Behav 140:107564

Bergner AS, Hildebrand C, Häubl G (2023) Machine talk: how verbal embodiment in conversational AI shapes consumer-brand relationships. J Consum Res 50(4):742–764

Bhardwaj, S, Sreen, N, Das, M, Chitnis, A, & Kumar, S (2023). Product specific values and personal values together better explains green purchase. J Retail Consum Serv 74:103434

Chen, CC, Chang, CH, & Hsiao, KL (2022). Exploring the factors of using mobile ticketing applications: perspectives from innovation resistance theory. J Retail Consum Serv 67:102974

Claudy MC, Garcia R, O’Driscoll A (2015) Consumer resistance to innovation-a behavioral reasoning perspective. J Acad Mark Sci 43(4):528–544

De Silva M, Wang PJ, Kuah ATH (2021) Why wouldn’t green appeal drive purchase intention? Moderation effects of consumption values in the UK and China. J Bus Res 122:713–724

Elhoushy, S, & Jang, S (2023). How to maintain sustainable consumer behaviours: a systematic review and future research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 47:2181–2211

Emonds T, Verwijmeren T, Müller BCN (2023) Lowering the barriers to change: can processing-related self-affirmations overcome resistance? J Appl Soc Psychol 53(10):925–937

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160

Fella, S, & Bausa, E (2024). Green or greenwashed? Examining consumers’ ability to identify greenwashing. J Environ Psychol 95:102281

Fernandez-Lores, S, Crespo-Tejero, N, Fernández-Hernández, R, & García-Muiña, FE (2024). Online product returns: The role of perceived environmental efficacy and post-purchase entrepreneurial cognitive dissonance. J Busi Res 174:114462

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Free, C, Jones, S, & Tremblay, MS (2024). Greenwashing and sustainability assurance: a review and call for future research. J Account Liter 10 0201

Gershoff AD, Frels JK (2015) What makes it green? The role of centrality of green attributes in evaluations of the greenness of products. J Mark 79(1):97–110

Girardin, F, Bezençon, V, & Lunardo, R (2021). Dealing with poor online ratings in the hospitality service industry: the mitigating power of corporate social responsibility activities. J Retail Consum Serv 63:102676

Gong SY, Wang L, Peverelli P, Suo DN (2022) When is sustainability an asset? The interaction effects between the green attributes and product category. J Prod Brand Manag 31(6):971–983

Graham-Rowe E, Jessop DC, Sparks P (2019) Self-affirmation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: promoting a reduction in household food waste. J Environ Psychol 62:124–132

Guan, DX, Lei, YF, Liu, Y, & Ma, QH (2024). The effect of matching promotion type with purchase type on green consumption. J Retail Consum Serv 78:103732

Habib, MD, Attri, R, Salam, MA, & Yaqub, MZ (2025). Bright and dark sides of green consumerism: an in-depth qualitative investigation in retailing context. J Retail Consum Serv 82:104145

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24

Jan, IU, Ji, SG, & Kim, C (2023). What (de) motivates customers to use AI-powered conversational agents for shopping? The extended behavioral reasoning perspective. J Retai Consum Serv 75:103440

Khan SJ, Badghish S, Kaur P, Sharma R, Dhir A (2023) What motivates the purchasing of green apparel products? A systematic review and future research agenda. Bus Strategy Environ 32(7):4183–4201

Lim RE, Lee WN (2023) Communicating corporate social responsibility: how fit, specificity, and cognitive fluency drive consumer skepticism and response. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30(2):955–967

Lima PAB, Falguera FPS, da, Silva HMR, Maciel S, Mariano EB, Elgaaied-Gambier L (2024) From green advertising to sustainable behavior: a systematic literature review through the lens of value-belief-norm framework. Int J Adv 43(1):53–96

Park JS, Ju I, Kim KE (2014) Direct-to-consumer antidepressant advertising and consumers’ optimistic bias about the future risk of depression: the moderating role of advertising skepticism. Health Commun 29(6):586–597

Peterson EB, Taber JM, Klein WMP (2022) Information avoidance, self-affirmation, and intentions to receive genomic sequencing results among members of an African descent cohort. Ann Behav Med 56(2):205–211

Philp, M, & Nepomuceno, MV (2024). How reviews influence product usage post-purchase: an examination of video game playtime. J Busi Res 172:114456

Pizzutti C, Goncalves R, Ferreira M (2022) Information search behavior at the post-purchase stage of the customer journey. J Acad Mark Sci 50(5):981–1010

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Policarpo MC, Apaolaza V, Hartmann P, Paredes MR, D’Souza C (2023) Social cynicism, greenwashing, and trust in green clothing brands. Int J Consum Stud 47(5):1950–1961

Qian, LX, Yin, JL, Huang, YL, & Liang, Y (2023). The role of values and ethics in influencing consumers’ intention to use autonomous vehicle hailing services. Technol Forecast Soc Change 188:122267

Rausch, TM, Baier, D, & Wening, S (2021). Does sustainability really matter to consumers? Assessing the importance of online shop and apparel product attributes. J Retail Consum Serv 63:102681

Riva, F, Magrizos, S, Rizomyliotis, I, & Uddin, MR (2024). Beyond the hype: deciphering brand trust amid sustainability skepticism. Busi Strategy Environ 33:6491–6506

Rizomyliotis I, Poulis A, Konstantoulaki K, Giovanis A (2021) Sustaining brand loyalty: the moderating role of green consumption values. Bus Strategy Environ 30(7):3025–3039

Rossi MV, Faggioni F, Sagona A, Sestino A(2024) Assessing the multifacetedness of greenwashing: implications for consumers, companies and societies Eur J Volunteer Community-based Proj 1(2):51–69

Sadiq M, Adil M, Paul J (2023) Organic food consumption and contextual factors: an attitude-behavior-context perspective. Bus Strategy Environ 32(6):3383–3397

Santos C, Coelho A, Marques A (2024) A systematic literature review on greenwashing and its relationship to stakeholders: state of art and future research agenda. Manag Rev Q 74(3):1397–1421

Shang, DW, Wu, WW, & Schroeder, D (2023). Exploring determinants of the green smart technology product adoption from a sustainability adapted value-belief-norm perspective. J Retail Consum Serv 70:103169

Sharma, N, Paço, A, Rocha, RG, Palazzo, M, & Siano, A (2023). Examining a theoretical model of eco-anxiety on consumers’ intentions towards green products. Corp Soc Respons Environ Manage 31:1868–1885

Skackauskiene, I, & Vilkaite-Vaitone, N (2023). Green marketing and customers’ purchasing behavior: a systematic literature review for future research agenda. Energies 16(1):456

Sokolova, T, Krishna, A, & Doring, T (2023). Paper meets plastic: the perceived environmental friendliness of product packaging. J Consum Res 50:468–491

Sreen, N, Dhir, A, Talwar, S, Tan, TM, & Alharbi, F (2021). Behavioral reasoning perspectives to brand love toward natural products: moderating role of environmental concern and household size. J Retail Consum Serv 61:102549

Starbucks (2020). Starbucks inspires ‘GOOD GOOD’ lifestyles towards a better planet. https://www.starbucks.com.cn/en/about/news/good-good-lifestyles-towards-a-better-planet/. Accessed 1 March 2025

Steele CM, Liu TJ (1983) Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. J Pers Soc Psychol 45(1):5–19

Steenis ND, van Herpen E, van der Lans IA, van Trijp HCM (2023) Partially green, wholly deceptive? How consumers respond to (in)consistently sustainable packaged products in the presence of sustainability claims. J Adv 52(2):159–178

Stockheim, I, Tevet, D, & Fenig, N (2024). Keen to advocate green: how green attributes drive product recommendations. J Clean Prod 434:140157

Sun J, Nazlan NH, Leung XY, Bai B (2020) A cute surprise”: examining the influence of meeting giveaways on word-of-mouth intention. J Hosp Tour Manag 45:456–463

Tao, ZB (2024). Do not walk into darkness in greenhushing: a cross-cultural study on why Chinese and South Korean corporations engage in greenhushing behavior. Busi Strategy Develop 7(2):e401

Tezer A, Bodur HO (2020) The greenconsumption effect: how using green products improves consumption experience. J Consum Res 47(1):25–39

Tian, ZY, Sun, XX, Wang, JG, Su, WH, & Li, G (2022). Factors affecting green purchase intention: a perspective of ethical decision making. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(18):191811151

Tonder, V, Saunders, SG, Fullerton, S, & De Beer, LT (2023). Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: the role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. J Retail Consum Serv 71:103190

Trudel R, Klein J, Sen S, Dawar N (2020) Feeling good by doing good: a selfish motivation for ethical choice. J Bus Ethics 166(1):39–49

Ünal, U, Bagci, RB, & Tasçioglu, M (2024). The perfect combination to win the competition: bringing sustainability and customer experience together. Busi Strategy Environ 33:4806–4824

Westaby JD (2005) Behavioral reasoning theory: Identifying new linkages underlying intentions and behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 98(2):97–120

Whang JB, Song JH, Lee JH (2024) Two important strategies to attenuate consumer purchase hesitation. Int J Adv 43(5):824–846

Zhao, HP, Yu, ML, Fu, SX, Cai, Z, Lim, ETK, & Tan, CW (2023). Disentangling consumers’ negative reactions to impulse buying in the context of in-app purchase: Insights from the affect-behavior-cognition model. Elect Comm Res Appl 62:101328

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. YT6000055,2025SKQ08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ conceptualized the study and provided funding for this research. QZ conducted the investigation. YZ and QZ performed data curation and wrote the original draft. XL revised this manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Study Ethics Committee of Beijing Forestry University (Approval No. BJFUPSY-2024-015, Approval Date March 7, 2024). The survey was conducted in full compliance with Beijing Forestry University’s ethical guidelines and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent between 30 May and 17 June 2024. Before viewing any survey items on Credamo, each potential respondent was shown an electronic consent screen that outlined the study’s purpose, assured anonymity, highlighted the voluntary nature of participation and the right to withdraw at any time, and noted the fixed honorarium. Only those who clicked “I agree” could proceed to the questionnaire, thereby formally giving consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Q. & Li, X. Addressing consumer skepticism: effects of post-purchase green attribute disclosure on consumer attitude change. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05556-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05556-7