Abstracts

We examine the role of common institutional ownership in promoting corporate green innovation, utilizing a comprehensive panel dataset of Chinese energy firms from 2009 to 2021. Our analysis reveals that both common institutional ownership and green common institutional ownership significantly enhance green innovation. Mechanism analyses indicate that common institutional ownership promotes corporate green innovation through governance, resource integration, and information advantage mechanisms, whereas green common institutional ownership primarily promotes green innovation through governance and information advantage mechanisms. Heterogeneity analyses further demonstrate that common institutional ownership exerts a greater impact on non-SOEs, firms in heavy-polluting industries, and those in industries with high financial constraints. Moreover, green common institutional ownership has a more pronounced influence on non-SOEs, firms in non-heavy-polluting industries, and those facing low financial constraints. Our findings contribute to the literature on the determinants of corporate green innovation and offer valuable insights for strengthening corporate environmental governance in emerging markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s achievements in carbon reduction are largely attributed to the promotion of green innovations by energy firms (Liu and Liang, 2013). By 2019, China had reduced its carbon intensity by 47.9% compared to 2005 and increased the share of non-fossil fuels in energy consumption to 15.3% (Zhao et al., 2022). In the clean energy sector, China’s installed clean energy capacity surged from 152.2 million kilowatts in 2007 to 1.06 billion kilowatts in 2021, nearly a sevenfold increase, largely driven by the rapid growth of green innovations. In the traditional energy sector, China has actively advanced carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology and launched over 40 demonstration projects with a total carbon capture capacity of 3 million tons per year (Zhao et al., 2022). Achieving such advancements requires the support of multiple stakeholders, including policymakers, corporate managers, and investors (Mazaj et al., 2022). In emerging markets like China, institutional investors, serving as a key force in external corporate governance, possess keen market insight and extensive experience in corporate governance. They can provide valuable external insights that support firms’ sustainable development and enhance strategic decision-making. However, some studies argue that institutional investors may also exploit their industry expertise to help invested firms circumvent green governance requirements. As institutional investors become more actively involved in corporate activities, both their potential for positive governance impact and their propensity for opportunistic behavior have become increasingly apparent. Therefore, this study primarily examines the impact of institutional investors on corporate green innovation, emphasizing their role as external governance agents. Notably, previous studies on institutional investors and green innovation have overlooked interactions among portfolio firms. Therefore, this study takes these interconnections into account and examines how common institutional ownership, a unique type of institutional ownership, influences corporate green innovation.

Common institutional ownership refers to the situation where institutional investors simultaneously hold equity stakes in multiple listed firms within the same industry. As this phenomenon becomes increasingly widespread and influential on emerging markets, such as China, Vietnam, and Brazil, common institutional ownership has exerted a significant impact on corporate decision-making. Prior studies indicate that common institutional investors possess stronger incentives to monitor managerial behavior and strengthen corporate governance (Edmans et al., 2019; He et al., 2019). However, limited studies have explored the impact of common institutional ownership on firms’ green behaviors. While existing studies have examined aspects such as corporate green transformation (Wu et al., 2023) and green investment (Lu et al., 2024), the impact of common institutional ownership on green innovation remains underexplored and empirically inconclusive. We argue that this inconsistency is closely linked to the dual externalities inherent in green innovation. Common institutional investors primarily engage in corporate governance with profit-oriented motives, but the dual externalities of green innovation make it challenging for firms to prioritize such initiatives as core strategic objectives (Rennings, 2000). For most manufacturing enterprises, green innovation is primarily manifested in end-of-pipe technologies and pollution control measures, which often fail to yield immediate or direct financial returns (Gaddy et al., 2017). The energy industry presents a special case, as firms in this industry are able to align profit motives with green development goals through multiple channels (Dong et al., 2021). First, traditional energy firms generate significant pollution and emissions during fossil fuel production and processing, attracting close scrutiny from regulatory authorities. Green innovation can significantly reduce these firms’ pollution risks, alleviate compliance burdens, and minimize regulatory interference in their production and operations, thereby improving financial performance (Li et al., 2020). Second, renewable energy firms can improve energy conversion efficiency and achieve competitive advantages over traditional counterparts by lowering production costs through green innovation (Guinot et al., 2022). Therefore, these characteristics make the energy sector a particularly suitable context for investigating the impact of common institutional ownership on green innovation.

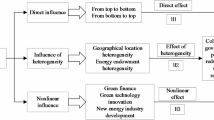

There are two competing views of the relationship between common institutional ownership and corporate green innovation: the coordination effect and the collusion effect. The first view—the coordination effect—suggests that common institutional ownership may promote the green innovation of portfolio firms through three primary channels: First, prior research finds that common institutional investors, as typically industry specialists, leverage governance and monitoring expertise acquired through block cross-holdings, thereby enhancing their monitoring effectiveness (Kang et al., 2018; Su et al., 2025). Therefore, we hypothesize that this expertise allows common institutional investors to better identify green governance challenges, and to gain board representation, thereby strengthening corporate green governance (Jiang and Liu, 2021; Dai et al., 2024). Second, prior research argues that common institutional investors facilitate resource coordination and optimize resource allocation (Li and Liu, 2023). Therefore, we hypothesize that common institutional ownership may strengthen green technology collaboration and foster green knowledge exploration (Audretsch et al., 2024). Third, existing research highlights that common institutional investors help mitigate information asymmetry and enhance corporate transparency (Park et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2024). Therefore, we hypothesize that common institutional ownership may reduce the cost of green information communication among portfolio firms and establish information advantages by enhancing the disclosure of corporate environmental responsibility. Conversely, the second view—the collusion effect—suggests that common institutional ownership may, actually, reduce corporate green innovation. Several studies contend that it may facilitate a collusive behavior among portfolio firms. In such cases, investors may even leverage their information and resources to obscure illegal activities, thereby undermining corporate legitimacy and managerial effectiveness. These practices, in turn, distort market competition and reduce the efficiency of resource allocation (Azar et al., 2018; Backus et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesize that common institutional ownership may increase the likelihood of environmental violations among portfolio firms. Accordingly, our objective is to determine which effect and through which specific mechanisms most accurately characterize the impact of common institutional ownership on green innovation.

Among institutional investors, green investors are a special type that has emerged in response to the need for low-carbon and sustainable development. They emphasize on the positive environmental and social externalities of their investments (Starks, 2023) and actively guide investee firms to achieve both financial performance and environmental objective (Sangiorgi and Schopohl, 2021). Green institutional investors often exhibit a proactive approach to corporate green innovation through three primary channels (Shi et al., 2024): First, green investors demonstrate a heightened sense of environmental responsibility and exhibit stronger incentives to monitor managerial behavior. They can enhance their “green” voting power through proxy solicitation or shareholder proposals, thereby ensuring the implementation of corporate green governance (Zhao et al., 2023). Second, green investors provide long-term and sustainable investments to alleviate financial constraints associated with green innovation (Feng and Yuan, 2024). Third, green investors promote greater transparency by encouraging the disclosure of corporate environmental and social responsibilities, thereby reducing information asymmetry between firms and external stakeholders(Shi et al., 2024; Feng and Yuan, 2024). However, limited studies have discussed whether and how interconnections among green investors affect corporate green innovation. Therefore, we further explore whether green common institutional ownership can effectively facilitate corporate green transformation.

To address the aforementioned issues, we conduct an empirical analysis using a sample of Chinese A-share listed energy firms from 2009 to 2021. This results indicate that both common institutional ownership and green common institutional ownership significantly promote green innovation in energy firms. These conclusions remain robust after addressing potential endogeneity concerns and conducting a series of robustness checks. Mechanism analyses reveal that both types of ownership exert a coordination effect. Specifically, the positive impact of common institutional ownership on green innovation operates through three key mechanisms: governance, resource integration, and information advantages. In contrast, green common institutional ownership enhances green innovation primarily through governance and information advantages. Heterogeneity analyses further demonstrate that common institutional ownership exerts a stronger influence on non-SOEs, firms in heavy-polluting industries, and those facing high financial constraints. Meanwhile, green common institutional ownership has a more pronounced impact on non-SOEs, firms in non-heavy-polluting industries, and those with low financial constraints.

This study contributes to the literature in four ways. First, it advances our understanding of the relationship between institutional ownership and corporate green innovation. Previous studies have documented a positive impact of institutional ownership on green innovation (Xu et al., 2023), often assuming that portfolio firms and their green innovation activities operate independently of one another. This study extends this line of the literature by showing that common institutional ownership—a distinctive and increasingly prevalent form of ownership—positively influences the corporate green innovation of portfolio firms. In contrast to Cheng et al. (2022), who argue that common institutional ownership inhibits corporate social responsibility through a collusion effect, our findings indicate that common institutional investors facilitate green innovation through a coordination effect. This expands the existing literature on the coordination role of common institutional ownership into the domain of environmental performance (Wu et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2024).

Second, we provide new insights into how common institutional ownership promotes green innovation through three distinct mechanisms—governance, resource integration, and information advantages. Similar to Dai et al. (2024), who find that common institutional ownership strengthens corporate governance by appointing directors to the board, we confirm the governance mechanism by showing that it increase the proportion of board members with environmental backgrounds. This advances the literature on the monitoring and governance roles of common institutional ownership (He et al., 2019). In line with Gao et al. (2019), who demonstrate that common institutional ownership promotes jointly owned patent applications, we confirm the resource integration mechanism by highlighting its role in facilitating green technological collaboration and promoting jointly owned green patents. This contributes to the literature on how common institutional ownership affects corporate resource integration (He and Huang, 2017). Furthermore, consistent with the findings of Tang et al. (2024), which show that common institutional ownership enhances corporate information disclosure and transparency, we confirm the information advantage mechanism by showing that it leads to greater disclosure of corporate environmental responsibility. This enriches the literature on the role of common institutional ownership on promoting information disclosure (Dai et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2024).

Third, we contribute to the research on green institutional investors by clarifying the mechanisms through which green common institutional ownership influences corporate green innovation. Our findings reveals that green common institutional ownership enhances corporate green innovation through governance and information channels. Furthermore, we compare these mechanisms with those of general common institutional ownership, providing both theoretical and economic rationale for their differential impacts. These results extend the literature on the impact of green institutional investors on corporate environmental performance (Shi et al., 2024; Feng and Yuan, 2024).

Fourth, this study enriches the understanding of common institutional ownership as an influential stakeholder in emerging markets. As common institutional ownership becomes increasingly prevalent in emerging markets, its role in corporate decision-making is becoming increasingly critical. We identify three specific mechanisms—corporate governance, resource integration, and information advantages—through which common institutional ownership promotes green innovation. Based on these mechanisms, we provide practical recommendations for how common institutional ownership can more effectively engage in corporate green governance initiatives in emerging markets. Our findings extend the arguments of Wu et al. (2022) and Lu et al. (2024) that common institutional ownership promotes the corporate adoption of environmental strategies.

The remainder of this paper is as follows: “Literature review and hypothesis development” presents a literature review and put hypotheses of this study. “Research Design” describes the model and data. “Empirical research and analysis” reports the results of baseline regression, endogeneity tests, robustness checks, mechanism analyses, and heterogeneity analyses. “Further analysis” provides further analysis. Finally, “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Literature review

The dual externalities of green innovation (Randjelovic et al., 2003; Lv et al., 2023) and the risks of corporate greenwashing (Huang et al., 2022) may result in investment term mismatches in green innovation (Jaffe et al., 2005; Lin and Ma, 2022). However, for energy firms, green innovation technologies are closely aligned with profit maximization. For traditional energy firms, green innovation can improve energy efficiency (Cheng et al., 2023), reduce the risk of negative environmental impacts during the manufacturing process (Yousaf et al., 2022), alleviate compliance burdens, and lower penalties imposed by regulatory authories, thereby enhancing financial performance (Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2023a). For clean energy firms, green innovation inherently enhances energy conversion efficiency, reduces production costs, gains competitive advantage, and increases corporate market value (Lv et al., 2023), thereby accelerating the displacement of traditional energy firms (Guinot et al., 2022). Therefore, the well-defined investment objectives of the energy sector provide a clear context for examining the relationship between common institutional ownership and green innovation.

A distinguishing feature of common institutional investors is their ability to foster social networks among firms within the same industry in their investment portfolios (Wu et al., 2022). However, previous studies have reached conflicting conclusions about the impact of these social networks on individual portfolio firms, presenting two distinctly opposing views. The first view argues that common institutional ownership fosters the coordination effect among firms held by the same institutional investors. Some studies consider that this coordination effect of is mainly reflected in the three aspects of governance mechanism, resource integration mechanism and information advantage mechanism. First, common institutional investors exhibits a stronger motivation to participate in the corporate governance of firms within their portfolio. Specifically, they can enhance monitoring effectiveness by sharing accumulated monitoring experience and governance expertise from one firm to another within the same industry (Kang et al., 2018; Su et al., 2025). Prior research has also validated that common institutional ownership improves corporate governance through voting at shareholders’ meetings, threatening to withdraw investments, and appointing directors to the boards of their portfolio firms (Edmans et al., 2019; Dai et al., 2024). Second, common institutional ownership enhances resource integration among portfolio firms. Specifically, it enables institutional investors to gain knowledge and resources from one firm and share them with another firm in the same industry (Gao et al., 2019). Prior research has also confirmed that common institutional investors promote explicit collaboration (He and Huang, 2017). These collaborative activities help reduce redundant R&D efforts, promote resource integration, and create competitive resource advantages (Li et al., 2023b; Li and Liu, 2023). Third, common institutional ownership helps portfolio firms build corporate information advantages. Its information transmission function extends beyond the dissemination of industry-wide knowledge. It also involves selectively sharing private information among firms within the investment portfolio (Cheng et al., 2022). Therefore, common institutional ownership can effectively reduce information search and processing cost for investors, reduce information asymmetry between investors and investing firms (Park et al., 2019), and enhance corporate information disclosure and transparency of corporate information (Tang et al., 2024). These improvements help investors and regulators enhance their trust in firms, and thus effectively strenthening corporate information advantages. Regarding corporate green development, prior studies have confirmed that the synergistic effect of common institutional investors positively influences corporate innovation (Li and Liu, 2023), corporate green transformation (Wu et al., 2022), and corporate green investment (Lu et al., 2024).

On the contrary, the second view suggests that common institutional ownership may have a collusion effect that impedes the growth of individual firms. As common institutional investors may pursue to maximize overall portfolio value and minimize resource waste within the portfolio, they thus choose to promote collective action that foster tacit collusion among portfolio firms (Azar et al., 2018). This collusion effect can enhance the bargaining power of portfolio firms, promote joint pricing, capture market share, achieve monopoly status, and gain excess profits. Ultimately, such practices reduces industry competition (Balsmeier et al., 2017), and undermines consumer welfare (Hariskos et al., 2022). This anti-competitive effect of common institutional ownership has a negative impact on corporate green behaviors such as corporate social responsibility (Cheng et al., 2022) and ESG performance (Lei, 2023).

The above studies on the role of common institutional ownership in corporate green innovation remain limited, and only a few have explored the impact of industry-firm linkage on green innovation based on social network theory. Among them, Tan et al. (2022) identify a synergistic effect of green innovation between upstream and downstream industries. Wu et al. (2023) reveal a cohort effect and upward convergence in green technological innovation among firms within the same industry. However, the specific impact of industry-firm linkages formed by common institutional ownership on green innovation has received limited attention. Only a few studies have touched on this topic. For instance, Wang (2023) highlights the positive role of investor communication in promoting green innovation. This study seeks to fill this gap by applying social network theory to the context of common ownership, thereby theoretically extending existing research on the determinants of corporate green innovation.

The impact of common institutional ownership on corporate green innovation

As discussed in “Literature review”, common institutional ownership exerts a coordination effect through three mechanisms: governance, resource integration, and information advantages. We hypothesize that common institutional ownership promotes green innovation among portfolio firms through these three mechanisms:

First, common institutional ownership may promote green innovation through its influence on corporate governance. It enables institutional investors to capture soft information and develop industry-specific expertise (Kang et al., 2018), which can be transferred across portfolio firms within the same industry to support governance and corporate decision-making (Wu et al., 2022). Through active participation in governance, common institutional ownership can fulfill its supervisory role and improve governance efficiency (He et al., 2019), for example, by appointing directors to the boards of portfolio firms (Dai et al., 2024). Based on this, we hypothesize that common institutional investors can leverage their governance experience to identify firms facing green governance challenges and enhance supervisory effectiveness by increasing the proportion of board members with environmental expertise. Board members with environmental expertise are better equipped to recognize the strategic value of sustainability practices—strategies that not only lower operational costs but also generate additional cash flow (Porter and Van der Linde, 1995). These improvements ultimately promote corporate green R&D and innovation.

Second, common institutional ownership can promote green innovation by enhancing resource integration among portfolio firms. It promotes inter-firm cooperation and resource sharing, expands access to scarce resources, optimizes resource allocation, and alleviates financial constraints (Li and Liu, 2023; He and Huang, 2017). Based on this, we hypothesize that common institutional ownership facilitates green technological collaboration and encourages the development of jointly owned green patents. By facilitating cross-firm collaboration in green technology, it helps firms minimize duplication in green R&D investments, optimize green resource allocation, and ultimately enhance their green innovation capabilities.

Third, common institutional ownership may foster green innovation by creating information advantages. It is more inclined to disclose firm-related information, such as CSR fulfillment, thereby increasing corporate information transparency (Liu et al., 2024). Specifically, in the context of green development, common institutional investors demonstrate a greater tendency to disclose corporate environmental responsibility information compared to general institutional investors (Mayew and Venkatachalam, 2012). Based on this, we hypothesize that common institutional ownership promotes the disclosure of environmental social responsibility, which in turn incentivizes firms to improve their green technologies in order to reflect their corporate environmental achievements (Xu et al., 2023). Moreover, it helps reduce information asymmetry between firms and the public, allowing the market to more accurately assess firm value (Park et al., 2019). This enhanced transparency can also attract additional investment and promote the firm’s green development (Liu et al., 2024). Greater transparency among portfolio firms also facilitates the exchange of private information and reduces information concealment driven by competitive tensions. This, in turn, helps to enhance the green innovation capacity of firms embedded in the network of common institutional ownership (Tang et al., 2024).

Based on the above analysis, we conclude that common institutional ownership can help solve the dual externalities of green innovation. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a. Common institutional ownership significantly promotes corporate green innovation.

Common institutional ownership can exert a collusion effect that inhibits corporate green innovation. Specifically, common institutional investors may collude with firms within their investment portfolios, thereby inhibiting corporate green innovation. Financial ties among portfolio firms may form a disguised monopoly, which reduces their incentives to compete in the market (Azar et al., 2018), and diminishes investment efficiency. Additionally, collusion among portfolio firms may increase the likelihood of environmental violations. Common institutional investors can leverage their industry experience and networks to encourage portfolio firms to imitate the environmental violations of others (Azar et al., 2018; Backus et al., 2021). Compared to isolated violations, which are more easily detected, portfolio firms can engage in more covert misconduct through mutual learning and informal communication, thereby making detection more difficult. This, in turn, lowers the expected costs of environmental noncompliance and increases potential benefits, thereby weakening firms’ incentives for corporate green innovation.

Therefore, we propose the following competing hypotheses:

H1b. Common institutional ownership significantly reduces corporate green innovation.

Research design

Sample selection and data sources

We construct a comprehensive dataset on common institutional ownership and green innovation performance of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2009 to 2021 in eight energy sectors. These sectors include both traditional and renewable energy industries: Solar, Wind, Hydro, Biomass, Geothermal, Fuel Cells, and Smart Grid. We screen energy-related industries based on the three-level classification of the 2021 Shenwan Industry Classification Standard, from which we extract a list of energy firms. To ensure the precision of the list, we individually review each firm’s annual report, and exclude firms whose business descriptions are unrelated to energy. We then reclassify these firms into the eight relevant energy sectors outlined aboveFootnote 1.

We obtain the data of green innovation patents from Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) database, where green patents are identified based on the IPC Green Inventory supplied by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). We obtaine institutional investor shareholding information and financial data from China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. We remove firms labeled as “ST” or “*ST”, as well as those with other abnormal business conditions. We also exclude observations with missing values in the variables. Finally, we obtaine 2924 firm-year observations from 363 energy firms. To eliminate the influence of outliers, we winsorize all continuous variables at the 1% and 99% percentiles of their distributions.

Model design and variable definitions

The following model (1) is constructed to estimate the impact of common institutional ownership on corporate green innovation. If \({\alpha }_{1}\) is significantly positive, it supports H1a, whereas if \({\alpha }_{1}\) is significantly negative, it supports H1b.

where i denotes the firm, t denotes the year and j indicates the industry. Greenpat is the explanatory variable, represented by the natural logarithm of the total number of green patent applications filed by the firm i in year t plus one (Brunnermeier and Cohen, 2003; Hu et al., 2021). To address concerns that patent counts alone may not fully capture the quality or completeness of green innovation (Trajtenberg, 1990; Popp, 2003), we also use the natural logarithm of the total number of green patent grants by firms i in year t plus one (Greenpated), and the natural logarithm of the total number of green patent citations by firm i in year t plus one (Greencited) as two alternative measures of firms’ green innovation outcomes in robustness checks.

Coz is the independent variable which measures the common institutional ownership. Following previous research (Cheng et al., 2022; He and Huang, 2017; Li and Liu, 2023), we define common institutional investors as those who simultaneously hold 5% or more ownership of at least one other same energy industry firm. Specifically, we exclude common institutional investors whose names contain the word “index” (Chemmanur et al., 2025), as index funds are passively managed and typically do not engage in corporate governance or decision-making (Attig et al., 2012). We construct three measures for common institutional ownership: (1) Coz1 is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the firm is held by a common institutional investor in any quarter of the year, and 0 otherwise; (2) Coz2 represents the number of industry peers that share at least one common institutional investor with other firms in same subsector during the year’s four quarters. To mitigate skewness, we apply the natural logarithm of Coz2 plus one in our regression models; (3) Coz3 is the sum of the average percentage holdings of all common institutional investors, averaged over the four quarters of the year.

We follow previous research (Wu et al., 2022; Li and Liu, 2023) to choose control variables to account for firm-level heterogeneity. First, we control for a series of variables that respond to the firm’s financial characteristics: firm size (Size), firm age (Age), financial leverage (Lev), operating income growth rate (Growth), and cash flow ratio (Cashflow). Second, we control for variables that affect corporate governance: the proportion of independent directors (Indep), board size (Board) and CEO duality (Dual). In addition, we also control for year (Year) and industry fixed effects (Ind). See Table 1 for the definitions of all variables.

Descriptive statistics analysis

Panel A of Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The mean and standard deviation of Greenpat are 1.383 and 1.462, respectively, and the standard deviation is higher than the mean, which means that different firms have large differences in the number of green innovations. The mean value of Coz1 is 0.193, indicating that 19.3% of the sample has common ownership. In addition, the mean value of Coz2 and Coz3 are 0.162 and 0.078, respectively, implying that, on average, each firm shares approximately 0.162 common institutional investors per year, with an average shareholding of 7.8%. Furthermore, we divide the sample into two groups based on common institutional ownership and then test the difference in the mean value of the green innovation variable between the two groups. As shown in Panel B of Table 2, the mean value of Greenpat or firms with common institutional investors is 2.292, which is significantly higher than 1.165 for firms without common investors.

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficient matrix for all variables. Most correlation coefficients are below 0.5, indicating low correlation among the variables and a low likelihood of multicollinearity.

Empirical results and analysis

Baseline regression analysis

Table 4 reports the baseline regression results examining the effect of common institutional ownership on green innovation in energy firms. We present the results with all control variables in Column (1)-(3). The coefficients of Coz1, Coz2 and Coz3 are all positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that common institutional ownership is positively associated with green innovation. Moreover, the positive effect is more pronounced in energy firms with a higher number of common institutional investors and greater ownership shares. From an economic perspective, the coefficient on Coz1 in Column (1) is 0.630, which shows that the number of firms’ green patent applications with common institutional ownership is approximately 0.033 higher than that of firms without common institutional ownership (\({e}^{-3.275}\times {(e}^{0.630}\)-1) = 0.033). The results in Column (4)-(9) with more strict fixed effect are also consistent. These results are consistent with prior studies documenting the positive effect of common institutional ownership on corporate environmental performance (Wu et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2024). Therefore, our baseline findings provide strong support for H1a and contribute to the literature emphasizing the coordination effect of common institutional ownership (He and Huang, 2017; Lewellen and Lowry, 2021; Li and Liu, 2023).

Endogeneity test

Although the baseline analysis demonstrates a positive impact of common institutional investors on energy firms’ green innovation, potential endogeneity concerns—such as reverse causality and omitted variable bias—need to be addressed. To mitigate these concerns, we conduct a series of endogeneity tests, and the empirical results are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Instrumental variables analysis

Considering that institutional investors are more likely to invest in firms with strong innovation capabilities rather than directly influencing their green innovation potential, we use the instrumental variables (IV) approach to address potential endogeneity concerns. Following (Goldsmith-Pinkham et al. (2020) and Chen et al., (2024), we construct a shift-share instrumental variable, denoted to as BartikIV. Specifically, BartikIV is defined as the national growth rate of common institutional investors across all listed energy firms, multiplied by the industry-level average number of common institutional investors, lagged by one period. The number of common institutional investors in the previous year can influence the their presence in the current year, satisfying the relevance condition. Moreover, because BartikIV is constructed based on exogenous national trends and lagged industry-level averages—rather than firm-level green innovation performance—it also satisfies the exogeneity condition. This design helps isolate the variation in common institutional ownership that is unrelated to firm-specific green innovation outcomes.

We employ a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation, and the results are reported in Table 5. In the first stage, the coefficients of the instrumental variables are all statistically significant, indicating that the product of the common institutional investor growth rate and the average number of green patents in the industry in the previous year are strongly related to firm-level common institutional investors. In the second stage, the coefficients on common institutional ownership remain significantly positive, indicating that there is no reverse causality, and supporting the conclusions of our baseline regression.

To assess the validity of the instrumental variables, we conduct a series of diagnostic tests, we use Kleibergen–Paap rk LM test to do under-identification test of instrumental variable, and the p-values of test are all less than 0.1, rejecting the null hypothesis of under-identification and indicating that the instruments are relevant. We also test the Kleibergen–Paap Wald rk F-statistics, and the F-statistics are above the conventional threshold of 10, indicating that the variable is not a weak instrumental variable. Finally, we also test the endogeneity of the instrumental variables, proven that the instrumental variable is exogenous. Therefore, the instrumental variable in our analysis is feasible. Overall, these results suggest that the instrumental variable used in our analysis is both relevant and valid, supporting the robustness of the causal inference.

Propensity score matching

Common institutional investors may be more likely to hold shares of firms with certain observable characteristics, potentially resulting in selection bias. To alleviate potential bias, we employ a propensity score matching (PSM) procedure and conduct post-matching regressions. Specifically, we estimate a logit model, in which the treatment variable is Coz1, all control variables are included as covariates in the matching process, and Greenpat is used as the outcome variable. We then obtain the treatment and matching samples by the PSM procedure using 1:1 nearest neighbor matching without the replacement method (with a caliper value of 0.03). The covariate balance test results (see Table 22) indicate that after matching, there are no significant differences in firm characteristics between the treated and control groups, confirming the effectiveness of the matching procedure. We then re-estimate the model using the mateched samples obtained from the PSM procedure. The results, presented in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 6, show that the coefficients of all three measures of common institutional ownership are still positive and significant at the 1% level. These findings are consistent with the baseline findings.

Heckman’s two-stage method

Another potential concern is that our findings may be affected by sample selection bias due to certain unobservable factors. We use Heckman’s two-stage method to address this concern. In the first stage, we employ a probit regression of the common institutional ownership variable (Coz1) on all control variables lagged by one period to calculate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). In the second stage, IMR is included as a control variable in model (1) to control for the effect of sample selection bias. The results are shown in Columns (4)-(6) of Table 6, indicating that the coefficients of common ownership are still positively significant. These findings further support the robustness of our main findings.

Lagged independent variables by two period

Given the time lag between the firms’ R&D activities and subsequent green patent outputs, we follow Bae et al. (2017) and Lu et al. (2024) by lagging all independent variables by two years to alleviate potential reverse causality bias. Columns (7)-(9) of Table 6 shows the results, which indicate that the coefficients of the two-period lagged common ownership are positively significant, consistent with the baseline results.

Robustness tests

Alternative measurement of dependent variables

To more accurately capture firms’ green innovation performance, we choose the natural logarithm of the number of green patent grants plus one (Greenpated) and the natural logarithm of the number of green patent citations plus one (Greencited) as two alternative measures of green innovation capability. As shown in Columns (1)–(6) of Table 7, common institutional investors also have a significantly positive impact on green patent grants and citations, which indicates that the results of baseline results remain robust.

Alternative measurement of independent variables

To evaluate whether our baseline findings remain valid when using alternative measures of common institutional ownership, we conduct a robustness test based on investors’ holding periods. Specifically, to address concerns that short-term institutional investors may not effectively promote green innovation, we reconstruct the three common ownership variables based on long-term institutional investors, defined as those whose average turnover rate falls in the bottom tertile (Gaspar et al., 2005). The results, shown in Columns (7)–(9) of Table 7, support the robustness of our baseline findings, even when the sample is restricted to long-term common institutional investors.

Replacement of model

Considering that our chosen proxy variable for green innovation, i.e., the total number of green patent applications, is a non-zero positive integer count variable, we further estimate a negative binomial regression model. This model is suitable for over-dispersed count data and is used to further assess the robustness of our findings. The results, presented in Columns (10)–(12) of Table 7, show that the coefficients on common institutional ownership remain significantly positive, reinforcing the robustness of our main findings.

Mechanism analysis

The previous results support the existence of a coordination effect of common institutional ownership on firms’ green innovation. We argue that this effect is mainly realized through three mechanisms: the governance mechanism, the resource integration mechanism and the information advantage mechanism. To test these mechanisms, we construct the following model:

where Mediating represents the mediating variable corresponding to each mechanism. Specifically, we use the following proxies: (i) the proportion of board members with environmental backgrounds to represent the governance mechanism; (ii) the natural logarithm of the number of green collaborative patents plus one to capture the resource integration mechanism; and (iii) the Bloomberg Environmental and Social Responsibility Disclosure Index to reflect the information advantage mechanism. The definitions of other variables remain consistent with those in Model (1). In this subsection, \({\gamma }_{1}\) is the coefficient of the main explanatory variable of focus, which captures the effect of common institutional ownership through these three channels.

Governance mechanism

According to the analysis in “The impact of common institutional ownership on corporate green innovation”, common institutional ownership may be able to strengthen corporate green innovation capability by improving their monitoring and governance roles. Common institutional investors may appoint directors to corporate boards to strengthen corporate green governance (Dai et al., 2024). Following Jiang and Liu (2021), we select the proportion of board members with environmental backgrounds (EP_ratio)Footnote 2 as the mediating variable to capture the governance mechanism. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 8 examine the effect of common institutional ownership on EP_ratio, and the coefficients of common institutional ownership are significantly positive at the 1% level. Columns (4)–(6) of Table 8 examines the coefficients of common institutional ownership after controlling for EP_ratio, and the coefficients of common institutional ownership are significantly positive at the 1% level. Therefore, it can be proved that common institutional ownership affects board composition, increases the oversight of management, and improves corporate green governance, thereby ultimately enhancing corporate green innovation. Our results enrich the literature by reinforcing the view that common institutional ownership plays a critical role in strengthening firms’ monitoring and governance functions (Kang et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2024).

Resource integration mechanism

According to the analysis in “The impact of common institutional ownership on corporate green innovation”, common institutional ownership can integrate green innovation resources by promoting green technology collaboration. This collaboration encourages the agglomeration of green innovation factors across portfolio firms and contributes to more efficient resource allocation. Following Gao et al., (2019), we select the logarithm of the number of jointly owned green patent applications (Greencoll) as the mediating variable representing the resource integration mechanism. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 9 present the regression results for the effect of common institutional ownership on Greencoll, and the coefficients of common institutional ownership are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. Columns (4)-(6) of Table 9 report the regression results after controlling for Greencoll, with the coefficients of common institutional ownership remain significantly positive at the 1% level. These findings suggest that common institutional ownership promotes green innovation by fostering resource integration among firms. These results extend the existing research by highlighting how common ownership enhances resource sharing and creates opportunities for collaboration among portfolio firms (He and Huang, 2017; Lewellen and Lowry, 2021).

Information advantage mechanism

According to the analysis in “The impact of common institutional ownership on corporate green innovation”, common institutional investors’ focus on corporate green development is also reflected in the enhanced corporate environmental responsibility disclosure and improved information transparency (Xu et al., 2023). Following Liu et al. (2024), we use the Bloomberg Environmental Social Responsibility Disclosure Index (BloombergE) as the proxy variable to capture information advantage mechanism in the regression analysis. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 10 report the results for the effect of common institutional ownership on BloombergE, and the coefficients of common institutional ownership are all significantly positive at 1% level. Columns (4)–(6) of Table 10 examine the results after controlling for BloombergE, and the coefficients of common institutional ownership remain significantly positive at the 1% level. These results suggest that common institutional ownership enhances public scrutiny and reduces information communication costs within the portfolio by increasing firms’ environmental responsibility disclosures. Consequently, it helps firms establish information advantages and improve their green innovation performance. Our findings contribute to the literature by confirming that common institutional ownership fosters corporate innovation through mitigating information asymmetry (Tang et al., 2024; Su et al., 2025).

Heterogeneity test

Heterogeneity of property rights

In China, the nature of a firm’s property rights is a non-negligible factor that affects the corporate decision-making. Differences in firms’ property rights can lead to significant variations in business strategies, governance structures, and information disclosures, ultimately affecting firm’s green innovation performance. In particular, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are often subject to more stringent government intervention. Chinese SOEs tend to suffer from significant agency problems, such as “absentee ownership” and “insider control” (Zhang et al., 2022), which lead to distorted governance mechanisms and relatively low information transparency (Zhang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). In contrast, non-SOEs are generally more market-orientated and exhibit greater transparency in information disclosure (Wang et al., 2024). To investigate the heterogeneous effects in the effects of common institutional ownership, we divide the sample into SOEs and non-SOEs. Table 11 presents the regression results. The coefficients of common institutional ownership are significantly positive at the 1% level for both groups. Notably, the coefficients of common institutional ownership for SOEs are smaller than those for the non-SOEs and the differences between the two sets of coefficients are statistically significant. These findings indicate that common institutional investors play a limited governance and monitoring role in promoting green innovation of SOEs. While they exhibit a stronger monitoring role in non-SOEs, thereby effectively promoting green innovation. This is consistent with previous studies showing that institutional investors often have limited influence on the strategic decision-making processes within SOEs, particularly with regard to innovation (Xu et al., 2023). Moreover, the results imply that the information advantage mechanism of common institutional investors is constrained in SOEs due to their insufficient information disclosure (Wang et al., 2024). Our results are consistent with the literature suggesting that state ownership moderates the effectiveness of common institutional ownership on corporate information disclosure (Wang et al., 2024). Overall, the results provide further evidence that common institutional ownership enhances green innovation primarily through governance and information advantage mechanisms, with the effectiveness of these channels contingent upon the nature of firms’ property rights.

Heterogeneity of the industry pollution levels

The discussion on the heterogeneity in green development is also closely related to differences in environmental pollution intensity across industries. Firms operating in heavy-polluting industries are subject to more stringent government regulations and face greater environmental risks and pressures, which necessitate more extensive financial support for their green transformation (Ge and Zhu, 2022). As a result, these firms often encounter higher financing constraints, leading to heterogeneity in how common institutional ownership affects green innovation across different industry types. To investigate this issue, we empirically divide our sample into two groups: firms in heavy-polluting industries and those in non-heavy-polluting industries. Table 12 reports the regression results that the coefficients on common institutional ownership are significantly positive for both groups. However, the coefficients for the heavy-polluting industries are larger than those for the non-heavy-polluting industries, and the differences between the groups are statistically significant. These results indicate that, compared with firms in non-heavy-polluting industries, common institutional ownership can better improve the green innovation of firms in heavy-polluting industries, which are more constrained in terms of financing. This finding confirms that common institutional investors can exert resource integration effects by promoting green technology collaboration. It helps portfolio firms minimize duplication in green R&D investment, optimize corporate resource allocation, and thereby alleviate corporate financial constraints (Li and Liu, 2023; He and Huang, 2017). Overall, the results provide further evidence that common institutional ownership promotes green innovation through the resource integration mechanism.

Heterogeneity of the industrial financial constraints

The level of industry-wide financial constraints may also constrain the green innovation activities among energy firms (Lu et al., 2024). Firms that lack access to green capital are more likely to introduce common institutional investors to optimize resource allocation and alleviate the financial pressure associated with green innovation. To test this hypothesis, we use the absolute value of the SA index, a widely used measure of financial constraints proposed by Hadlock and Pierce (2010), to measure firms’ financial constraints. The larger the SA index, the more serious financial constraints the firm confronts. We divide the sample into two groups based on the median value of the SA index. Firms in industries with SA index values above the median are considered to face high financial constraints, whereas those below the median are classified as having low financial constraints. Table 13 shows the regression results. We find that the coefficients of common institutional ownership are significantly positive in industries with high financial constraints, but not significant in those in industries with low financial constraints. Moreover, the coefficient difference between the two groups are significant. These findings suggest that the positive effect of common institutional ownership on green innovation is more pronounced in industries with high financial constraints. This provides further support for the resource integration mechanism, wherein common institutional ownership helps firms overcome financial barriers by improving resource coordination. Overall, the results reinforce the conclusion that common institutional ownership promotes green innovation by alleviating financial constraints through enhanced resource integration.

Further analysis

Impact of green common institutional ownership on green innovation of energy firms

Among common institutional investors, green common institutional investors place particular emphasis on the green development of energy firms. Through enhanced monitoring and governance, they can encourage management to incorporate environmental considerations into strategic decision-making, thereby potentially promoting green innovation. To further explore this effect, we examine the impact and underlying mechanism of green common institutional investors on green innovation of energy firms. Following Shi et al. (2024), we define green institutional investors as those whose names, investment objectives, or investment scopes include “environment”, “environmental protection”, “new energy”, “clean energy”, “ecology”, “low carbon”, “sustainable”, “energy-saving”, “green” and other keywords. In line with He and Huang (2017) and Chen et al. (2021), we define green common institutional investors as green investors who simultaneously hold 5% or more ownership in two or more firms within the same energy industry. Based on this definition, we construct three measures for green common institutional ownership: (1) a dummy variable for the existence of a green common institutional investor in the firm (GreenCoz1); (2) the natural logarithm of the number of green common institutional investors plus one in the firm (GreenCoz2); (3) the sum of the average percentage holdings of all green common institutional investors in the firm (GreenCoz3).

Table 14 reports the empirical results on the impact of green common institutional ownership on energy firms’ green innovation. Columns (1)–(3) present the baseline regressions results with all control variables, and year fixed and industry fixed effects included. Columns (4)–(6) add province fixed effects, while Columns (7)–(9) further incorporate industry-by-year and province-by-year fixed effects to control for unobservable heterogeneity across industries and regions over time. Across all model specifications, the coefficients of GreenCoz1, GreenCoz2 and GreenCoz3 are positive and significant at the 1% level, reflecting that green common institutional ownership significantly enhances corporate green innovation. Furthermore, both the number of green common institutional investors and their shareholding percentages are positively associated with firms’ green innovation output. From an economic perspective, the coefficient on GreenCoz1 in Column (1) is 0.512, implying that firms with green common institutional investors create, on average, 0.016 more green patents than those without (\({e}^{-3.723}\times {(e}^{0.512}\)-1) = 0.016), holding other factors constant. These findings provide strong empirical support for the view that green institutional investors play a constructive role in advancing firms’ environmental performance (Shi et al., 2024; Feng and Yuan, 2024). To address potential endogeneity concerns, we further conduct a series of robustness checks. These include the instrumental variable method, propensity score matching, Heckman’s two-stage selection model, and the use of a two-period lagged independent variable. The findings remain consistent across these methods, as reported in Tables 23–25. In addition, we test the robustness of our results by (i) replacing the dependent variables, (ii) using alternative measures of the independent variables, and (iii) employing a negative binomial regression model. The core findings remain unchanged, reinforcing the robustness of our findings. These results are reported in Table 26.

Mechanism test of green common institutional ownership on green innovation of energy firms

Theoretically, green common institutional ownership can similarly enhance the green innovation performance of energy firms through governance mechanisms, resource integration mechanisms and information advantage mechanisms. First, green institutional investors have professional environmental knowledge and green governance experience in green governance. This expertise enables them to better help firms identify environmental violations and enhance corporate green governance. In response, corporate managers, aware of the potential reputational damage and regulatory risks associated with environmental misconduct, are more likely to prioritize long-term strategic goals by investing in green innovation. Additionally, green investors can increase their “green” voting power by soliciting proxy votes or shareholder proposals, and ensure the implementation of their intentions through various supervisory methods such as participating in investment decisions and maintaining direct communicating with management (Zhao et al., 2023). Second, green institutional investors typically exhibit lower sensitivity to short-term financial returns and are more willing to prioritize long-term sustainable development (Kordsachia et al., 2022). This green investment preference allows them to support firms in undertaking green projects that may not yield immediate economic benefits, thereby alleviating financial constraints and facilitating long-term green innovation (Feng and Yuan, 2024). Finally, because green institutional investors require firms to actively fulfill their environmental and social responsibilities, which in turn enhances corporate reputation and signals strong environmental commitment to external stakeholders. This positive signaling effect can attract greater attention from governments, investors, media, and the general public (Gu et al., 2022). Consequently, firms can mitigate information asymmetry and build an informational advantage that further supports its green innovation efforts (Feng and Yuan, 2024) .

We further examine the governance, resource integration, and information advantage mechanisms through which green common institutional ownership influences green innovation in energy firms, following the methodology outlined in “Instrumental variables analysis”. The results are shown in Tables 15– 17. First, Table 15 reports that green common institutional ownership can also promote green innovation in energy firms by improving corporate green governance. Second, as shown in Table 16, the coefficients of green common institutional ownership become insignificant after controlling for the mediating variables. This indicates that resource integration, proxied by jointly owned green patent applications, does not mediate the relationship between green common institutional ownership and corporate green innovation. Third, Table 17 provides evidence that green common institutional ownership promotes green innovation by establishing information advantages, consistent with the information advantage mechanism. Taken together, these findings indicate that, compared with general common institutional ownership, green common institutional ownership primarily promotes green innovation through governance and information advantage mechanisms, rather than through resource integration. We argue that green investors primarily serve as a form of green supervision and signaling mechanism. Their presence indirectly pressures firms to adjust their operations to achieve positive environmental and social outcomes (Feng and Yuan, 2024), but they do not directly facilitate the sharing and integration of green resources across firms.

Heterogeneity test of green common institutional ownership on green innovation of energy firms

We also examine whether firms’ property rights, industry pollution level, and industry-level financial constraints lead to heterogeneous effects of green common institutional investors on green innovation.

The results of the heterogeneity test of firms’ property rights are shown in Table 18. We find that the coefficients of green common institutional ownership are significantly larger for non-SOEs than for SOEs, and the differences between the groups are all statistically significant. These results show that green common institutional ownership has a stronger positive impact on green innovation in non-SOEs. This finding is consistent with the argument that, similar to general common institutional investors, green common institutional ownership has green monitoring and governance incentives, and can promote green information disclosure. This finding also further provides evidence that green common institutional ownership can promote green innovation through governance and information advantage mechanisms.

Table 19 shows the results of the heterogeneity test for the industry pollution level. We find that the coefficients of green common institutional ownership are significantly larger for firms in non-heavy-polluting industries than for those in heavy-polluting industries, and the differences in coefficients between the groups are all significant. These results suggest that green common institutional ownership has a stronger impact on green innovation in non-heavy-polluting industries. One possible explanation for this pattern is that green common institutional investors do not directly facilitate the sharing and integration of green resources across firms, which may limit their influence in industries where large-scale, coordinated technological transformation is required—such as in heavy-polluting sectors. The reason for such a consistent impact of green institutional investors may be due to the attributes of their investors, i.e., focusing on the green development of firms, and therefore for any firm, green common institutional investors are involved in the corporate development mainly by utilizing their environmental experiences in green development. This finding provides additional evidence that, unlike general common institutional ownership, green common institutional ownership primarily promotes green innovation through governance and signaling mechanisms, but is less effective in driving resource integration, especially in industries with complex pollution challenges.

Finally, the heterogeneity test results based on industry-level financing constraints, as shown in Table 20, reveal that the coefficients of green common institutional ownership on green innovation are significantly positive across both groups. However, the coefficients are higher for industries with low financial constraints than for those with high financial constraints, and the differences between the groups are statistically significant. This indicates that green common institutional ownership has a stronger impact on green innovation in industries with low financial constraints. A possible explanation is that green common institutional investors do not exert resource integration mechanisms. In industries with high financing constraints, where green innovation often requires greater capital coordination, the lack of direct inter-firm resource integration limits the influence of green institutional investors. This finding also further provides evidence that green common institutional ownership cannot promote green innovation through resource integration mechanisms.

Conclusion

This study examines the impact of common institutional ownership on green innovation using a sample of A-share listed energy firms in China from 2009 to 2021. The empirical results show that common institutional ownership significantly improves firms’ green innovation performance. Mechanism analyses further reveal that this effect is primarily driven by three mechanisms: governance mechanism, resource integration mechanism and information advantage mechanism. These findings contribute to the growing literature on the coordination effect of common institutional ownership in the context of corporate environmental performance (He and Huang, 2017; Lewellen and Lowry, 2021; Li and Liu, 2023). Furthermore, heterogeneity tests show that the effect of common institutional ownership is more pronounced for non-SOEs, for firms in heavy-polluting industries, and industries with high financial constraints. In addition, this study extends the analysis to examine the role of green common institutional ownership on green innovation, and the results confirm that green common institutional ownership can also significantly enhance green innovation. However, mechanism analysis indicates that its influence operates mainly through governance and information advantage mechanisms, with no significant evidence supporting the resource integration mechanism. Our results extend the literature related to the positive effect of green institutional investors in corporate environmental performance (Shi et al., 2024; Feng and Yuan, 2024). Heterogeneity tests further indicate that the effect of green common institutional investors is more pronounced for non-SOEs, for firms in non-heavy-polluting industries, and industries with low financial constraints.

Based on the findings of this study, we offer the following recommendations: First, firms—particularly those in the energy sector— should actively introduce common institutional investors, as they play a crucial role in enhancing corporate green governance, fostering green technology collaboration, and increasing the transparency of green information disclosure. By leveraging the governance, resource integration, and information advantage mechanisms associated with common institutional ownership, firms can create a more conducive environment for sustainable innovation. At the same time, firms should also prioritize attracting green common institutional investors, who possess environmental expertise and long-term sustainability orientation. Their involvement can further strengthen green governance and improve the accessibility and accuracy of green information, thereby enabling more informed and effective decision-making regarding green innovation and sustainability strategies. Additionally, firms in heavy-polluting industries and those facing high financial constraints should take more proactive steps in engaging common institutional investors. Given the heightened impact of common institutional ownership in such contexts, institutional engagement can serve as a critical lever to overcome financing and governance barriers to green innovation.

Second, regulatory agencies should recognize the substantial role played by both common institutional investors and green institutional investors in driving green innovation among Chinese energy firms. Given their ability to enhance corporate governance and improve information efficiency, policymakers are encouraged to design regulatory frameworks that actively incentivize institutional investors to engage in coordinated, responsible ownership. To achieve this, the government could consider introducing targeted measures, such as encouraging responsible investment practices through guidelines and best practice frameworks, offering financial incentives or tax benefits for green institutional investment, and strengthening disclosure requirements related to corporate green innovation strategies and outcomes. Such measures would not only amplify the governance and signaling effects of institutional investors but also contribute to the broader national strategy of sustainable development and green transformation.

Data availability

The data is available from the CSMAR (China Stock Market & Accounting Research) database (https://data.csmar.com) and CNRDS (China National Economic and Social Development Statistics) database (https://www.cnrds.com). Both CSMAR and CNRDS are typically available through academic institutions, particularly those in China or with a focus on Chinese markets.

Notes

Some energy firms operate in multiple energy industries. as disclosed in their annual reports. For example, in the case of Shenzhen Energy, its business is dominated by Traditional Energy, but it also includes Solar, Hydro, Wind and Biomass businesses. To comprehensively reflect such diversified business participation, we reclassify Shenzhen Energy’s industries into Traditional Energy; Solar; Hydro; Wind; and Biomass in the baseline regression. To avoid potential bias in from the small proportion of non-core energy businesses in some firms, we recalculate the three common institutional ownership measures based solely on the primary business industry of each firm. For example, we classify Shenzhen Energy into Traditional Energy in this robustness test. The results in Columns (1)-(3) of Table 21 support our baseline results. We also recalculate the three common institutional ownership measures in energy firms based on the secondary industry classification of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). The results in Columns (4)-(6) of Table 21 support our baseline results. Furthermore, we expand the sample scope to the entire manufacturing industry. We recalculate the three common institutional ownership measures in manufacturing firms based on the secondary industry classification of the CSRC. The results in Columns (7)-(9) of Table 21 remain consistent with our baseline results.

We collect data on the board members with environmental backgrounds from biographical information published on the Sina Finance website, for example, if biographies include “environment”, “environmental protection”, “new energy”, “clean energy”, “ecology”, “low carbon”, “sustainable”, “energy-saving”, “green” and other keywords, that member is identified as having an environmental background. We count the number of board members with environmental backgrounds based on this criterion.

References

Attig N, Cleary S, El Ghoul S, Guedhami O (2012) Institutional investment horizon and investment-cash flow sensitivity. J Bank Financ 36(4):1164–1180

Audretsch DB, Belitski M (2024) Geography of knowledge collaboration and innovation in Schumpeterian firms. Reg Stud 58(4):821–840

Azar J, Schmalz MC, Tecu I (2018) Anticompetitive effects of common ownership. J Financ 73(4):1513–1565

Backus M, Conlon C, Sinkinson M (2021) Common ownership in America: 1980–2017. Am Econ J Microecon 13(3):273–308

Bae J, Kim SJ, Oh H (2017) Taming polysemous signals: The role of marketing intensity on the relationship between financial leverage and firm performance. Rev Financ Econ 33(1):29–40

Balsmeier B, Fleming L, Manso G (2017) Independent boards and innovation. J Financ Econ 123(3):536–557

Brunnermeier SB, Cohen MA (2003) Determinants of environmental innovation in US manufacturing industries. J Environ Econ Manag 45(2):278–293

Chemmanur TJ, Shen Y, Xie J (2025) Unlocking strategic alliances: The role of common institutional blockholders in promoting collaboration and trust. J Financ Stab 76:101350

Chen Y, Li Q, Ng J, Wang C (2021) Corporate financing of investment opportunities in a world of institutional cross-ownership. J Corp Financ 69:102041

Chen Z, Zuo W, Xie G (2024) How does institutional investor preference influence corporate green innovation in China. Eur J Financ 30(11):1239–1269

Cheng X, Wang H, Wang X (2022) Common institutional ownership and corporate social responsibility. J Bank Financ 136:106218

Cheng X, Chen K, Su Y (2023) Green innovation in oil and gas exploration and production for meeting the sustainability goals. Resour Policy 87:104315

Dai J, Xu R, Zhu T, Lu C (2024) Common institutional ownership and opportunistic insider selling: Evidence from China. Pac Basin Financ J 88:102580

Dong W, Li Y, Lv X, Yu C (2021) How does venture capital spur the innovation of environmentally friendly firms? Evidence from China. Energy Econ 103:105582

Edmans A, Levit D, Reilly D (2019) Governance under common ownership. Rev Financ Stud 32(7):2673–2719

Feng J, Yuan Y (2024) Green investors and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 60:104892

Gaddy BE, Sivaram V, Jones TB, Wayman L (2017) Venture capital and cleantech: The wrong model for energy innovation. Energy Policy 102:385–395

Gao K, Shen H, Gao X, Chan KC (2019) The power of sharing: Evidence from institutional investor cross-ownership and corporate innovation. Int Rev Econ Financ 63:284–296

Gaspar JM, Massa M, Matos P (2005) Shareholder investment horizons and the market for corporate control. J Financ Econ 76(1):135–165

Ge Y, Zhu Y (2022) Boosting green recovery: Green credit policy in heavily polluted industries and stock price crash risk. Resour Policy 79:103058

Goldsmith-Pinkham P, Sorkin I, Swift H (2020) Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how. Am Econ Rev 110(8):2586–2624

Gu Y, Ho KC, Xia S, Yan C (2022) Do public environmental concerns promote new energy enterprises’ development? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Energy Econ 109:105967

Guinot J, Barghouti Z, Chiva R (2022) Understanding green innovation: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 14(10):5787

Hadlock CJ, Pierce JR (2010) New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev Financ Stud 23(5):1909–1940

Hariskos W, Konigstein M, Papadopoulos KG (2022) Anti-competitive effects of partial cross-ownership: Experimental evidence. J Econ Behav Organ 193:399–409

He J, Huang J (2017) Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: Evidence from institutional blockholdings. Rev Financ Stud 30(8):2674–2718

He J, Huang J, Zhao S (2019) Internalizing governance externalities: The role of institutional cross-ownership. J Financ Econ 134(2):400–418

Hu G, Wang X, Wang Y (2021) Can the green credit policy stimulate green innovation in heavy polluting enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ 98:105134

Huang R, Xie X, Zhou H (2022) Isomorphic’ behavior of corporate greenwashing. Chin J Popul Resour Environ 20(1):29–39

Jaffe AB, Newell RG, Stavins RN (2005) A tale of two market failures: Technology and environmental policy. Ecol Econ 54(2-3):164–174

Jiang GJ, Liu C (2021) Getting on board: the monitoring effect of institutional directors. J Corp Financ 67:101865

Kang JK, Luo J, Na HS (2018) Are institutional investors with multiple blockholdings effective monitors? J Financ Econ 128(3):576–602

Kordsachia O, Focke M, Velte P (2022) Do sustainable institutional investors contribute to firms’ environmental performance? Empirical evidence from Europe. Rev Manag Sci 16(5):1409–1436

Lei L, Zhang DY, Ji Q (2023) Common institutional ownership and corporate ESG performance. Econ Res J 4:133–151

Lewellen K, Lowry M (2021) Does common ownership really increase firm coordination? J Financ Econ 141(1):322–344

Li J, Liu L (2023) Common institutional ownership and corporate innovation: synergy of interests or grabs of interests. Financ Res Lett 52:103512

Li L, Msaad H, Sun H, Tan MX, Lu Y, Lau AK (2020) Green innovation and business sustainability: New evidence from energy intensive industry in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(21):7826

Li N, Dilanchiev A, Mustafa G (2023a) From oil and mineral extraction to renewable energy: Analyzing the efficiency of green technology innovation in the transformation of the oil and gas sector in the extractive industry. Resour Policy 86:104080

Li X, Liu T, Taylor LA (2023b) Common ownership and innovation efficiency. J Financ Econ 147(3):475–497

Lin B, Ma R (2022) How does digital finance influence green technology innovation in China? Evidence from the financing constraints perspective. J Environ Manag 320:115833

Liu H, Liang D (2013) A review of clean energy innovation and technology transfer in China. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 18:486–498

Liu Y, Jin XM, Ly KC, Mai Y (2024) The relationship between heterogeneous Institutional investors' shareholdings and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China. Res Int Bus Finance 71:102457

Lu C, Zhu T, Xia X, Zhao Z, Zhao Y (2024) Common institutional ownership and corporate green investment: Evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 91:1123–1149

Lv X, Liu T, Dong W, Su W (2023) The market value of green innovation: A comparative analysis of global renewable energy firms. Financ Res Lett 51:103490

Mayew WJ, Venkatachalam M (2012) The power of voice: Managerial affective states and future firm performance. J Financ 67(1):1–43

Mazaj J, Picone PM, Destri AML (2022) Stakeholder Involvement in Sustainable Innovation: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework. In: Sustainability in the Gig Economy: Perspectives, Challenges and Opportunities in Industry 4.0. Springer, Singapore, pp 49–64

Park J, Sani J, Shroff N, White H (2019) Disclosure incentives when competing firms have common ownership. J Acc Econ 67(2-3):387–415

Popp D (2003) Pollution control innovations and the clean air act of 1990. J Policy Anal Manag 22(4):641–660

Porter M, Van der Linde C (1995) Green and competitive: ending the stalemate. Harv Bus Rev 33:129–134

Randjelovic J, O’Rourke AR, Orsato RJ (2003) The emergence of green venture capital. Bus Strategy Environ 12(4):240–253

Rennings K (2000) Redefining innovation—eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol Econ 32(2):319–332

Sangiorgi I, Schopohl L (2021) Why do institutional investors buy green bonds: Evidence from a survey of European asset managers. Int Rev Financ Anal 75:101738

Shi B, Wang X, Jiang X, Yang H, Sui W (2024) Green institutional investors' shareholding and corporate environmental responsibility. Financ Res Lett 62:105232

Starks LT (2023) Presidential address: Sustainable finance and ESG issues—Value versus values. J Financ 78(4):1837–1872

Su Y, Liu F, Tao J, Du J (2025) Common institutional ownership and corporate green transition: promotion or inhibition? Emerg Mark Finance Trade 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2024.2444509

Tan X, Yan Y, Dong Y (2022) Peer effect in green credit induced green innovation: An empirical study from China’s green credit guidelines. Resour Policy 76:102619