Abstract

Zombie firms hinder the healthy development of the economy and society and may also affect labor mobility. Using microdata from the 2000–2015 population censuses and the Chinese industrial enterprises database from 1998 to 2013, this paper empirically examines the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility and the underlying mechanisms at the city level. The findings reveal that an increase in the proportion of zombie firms in a city significantly suppresses labor inflows and accelerates labor outflows. Mechanism analysis shows that zombie firms affect labor mobility by solidifying the industrial structure, obstructing the entry of new firms, and exacerbating environmental pollution. Further research indicates that the impact of zombie firms exhibits individual heterogeneity, with low-skilled and younger and middle-aged workers being more susceptible to the negative effects of zombie firms. This study not only provides new literature and empirical evidence on the impact of zombie firms on the labor market but also offers important insights for local governments on attracting labor and preventing labor loss by addressing the issue of zombie firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The labor force is a crucial driving force supporting the sustained and healthy development of China’s economy. In recent years, with the gradual loosening of the household registration system and the rapid advancement of urbanization, labor mobility across the country has been steadily increasing (Qi et al., 2015; Hu and Jia, 2025). According to the Seventh National Population Census released by the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s total floating population reached 376 million in 2020, a nearly 19-fold increase compared to 1990.Footnote 1 The “flowing China” highlights the resilience and vitality of China’s economy and is a key factor in the nation’s contemporary prosperity, however, it also reflects the challenges faced by certain cities and regions experiencing continuous labor outflows. Data from China’s sixth and seventh population censuses indicate that, compared to 2010, 219 out of 284 cities experienced a net outflow of labor in 2020. In particular, in the Northeast region, where economic growth has lagged in recent years, more than 90% of cities have experienced a net loss of labor. In contrast, in the Eastern region, which is leading the national economic transformation and upgrading, more than 40% of cities have experienced a net inflow of labor.Footnote 2

Labor mobility is closely linked to economic development across different regions. The disparities in economic development and wage levels between regions are the primary drivers of interregional labor mobility (Wang and Jia, 2021). Numerous studies have confirmed that relatively higher wages, more employment opportunities (Peng, 2015), and better education or healthcare services (Xia and Lu, 2015) in the destination region are key factors attracting labor inflows. Therefore, the level of regional economic development is an important factor influencing the choice of destination for labor mobility. In contrast, industry, as the basis of regional economic development, is the core of population competitiveness. Since the reform and opening up, certain regions along China’s eastern coast, pioneers in establishing a competitive market mechanism, have rapidly mastered the evolving pathways of global industrial development. These regions were the first to establish an industrial base that drives regional development, attracting a large inflow of labor and significantly boosting regional economic growth. This fact undeniably demonstrates that the industrial foundation constitutes a critical factor in a region’s capacity to attract labor inflow. Regions with well-developed industries can provide the labor force with more abundant employment opportunities, more generous economic benefits, and a better quality of life, thus attracting a constant inflow of labor. Conversely, regions with underdeveloped industries gradually lose their appeal to the labor force, leading to a continuous outflow of labor.

From the perspective of China’s industrial development, the growth of various regions in recent years has been significantly affected by the presence of zombie firms. Zombie firms generally refer to inefficient enterprises that, despite lacking sustainable profitability, continue to operate and remain in the market without exiting. Multiple measurement methods indicate that, from 2001 to 2013, the proportion of zombie firms among China’s industrial enterprises above designated size was over 7%, and the proportion among listed companies from 2003 to 2015 exceeded 10% (Nie et al., 2016). Regarding regional distribution, the proportion of zombie firms among listed companies in all regions—whether in the eastern, central, western, or northeastern areas—was above 8% between 2007 and 2018, but substantial differences exist between regions. Notably, the northeastern and western regions, where labor outflows have been particularly severe in recent years, exhibit higher levels of firms’ zombification, while the eastern region, which serves as the primary destination for labor mobility in China, has relatively lower levels of firms’ zombification (Huang and Chen, 2017; Sheng, 2022).

Zombie firms, characterized by inefficiency and an inability to generate profits, continue to operate primarily due to external support from banks and local governments. The long-term entrenchment of a large number of zombie firms within the industrial system exacerbates the misallocation of local resources, undermines the market selection mechanism of survival of the fittest during regional industrial development, disrupts the normal market entry and exit processes, and stifles the growth potential of viable enterprises, thereby squeezing the space available for high-quality firms. The resource misallocation effects caused by zombie firms have serious negative impacts on regional industrial upgrading (Geng et al., 2021), employment growth (Xiao et al., 2019), and environmental pollution (Wu, 2021). These impacts can weaken a region’s attractiveness and competitiveness, further reducing the willingness of the labor force to remain or enter, ultimately leading to significant labor outflows. In reality, many cities in China’s northeastern region, where the problem of zombie firms is most severe, as well as certain cities in the central and western regions, have faced the stark challenge of large-scale labor “flight” in recent years. Therefore, has the presence of zombie firms affected labor mobility? If so, what mechanisms are primarily at play? These are the key questions that this paper seeks to explore.

The negative impact of zombie firms on economic and social development has been widely studied, but few studies have linked the issue of zombie firms with labor mobility, specifically exploring the effects of zombie firms on labor mobility and the underlying mechanisms. Although some literature has addressed the impact of zombie firms on the labor market, such as the work by Xiao et al. (2019), which found that the presence of zombie firms crowds out the credit resources available to normal firms (i.e., non-zombie firms), thereby inhibiting their employment growth. Qiao and Song (2022) argued that zombie firms suppress job creation by normal firms through the crowding-out effect on credit resources, disrupting the efficient allocation of local labor resources. These studies primarily focus on the micro-level effects of zombie firms on labor resource misallocation and do not examine the impact of zombie firms on spatial labor mobility, nor do they discuss how zombie firms affect interregional labor movement. This paper is interested in whether the widespread proliferation of zombie firms, leading to severe local resource misallocation, inhibits regional industrial upgrading, causes industrial structure rigidity, and subsequently results in local labor outflows. Building on the hypothesis that zombie firms hinder the entry of normal firms, this paper also investigates whether zombie firms reduce the number of new business registrations in a region, thereby diminishing employment opportunities and influencing labor mobility decisions. Additionally, we will examine whether the presence of zombie firms affects labor mobility decisions by altering comprehensive factors that influence labor’s choice of employment location, such as local environmental quality.

Compared to the existing literature, this paper contributes in two main areas: First, although some studies have discussed the negative impacts of zombie firms on the labor market, they have primarily focused on aspects such as employment growth and labor resource allocation, often conducting analyses at the micro level. In contrast, this paper emphasizes an urban perspective, empirically examining the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility, thereby enriching the existing research on the effects of zombie firms. Second, this paper investigates urban labor outflows induced by zombie firms through three distinct dimensions: industrial structure rigidity, barriers to firm entry, and worsening of environmental pollution. Doing so clearly reveals the effects of zombie firms on labor mobility, effectively capturing the mechanisms by which zombie firms contribute to urban labor mobility. This provides a new perspective and empirical evidence for studying the factors influencing labor mobility. Additionally, this research, from the perspective of zombie firms, offers a novel and plausible explanation for the significant labor outflows observed in regions such as northeastern China in recent years.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section “Literature review and theoretical analysis” provides a literature review and presents the analysis of theoretical mechanisms. Section “Model setting and variable description” constructs the econometric model and describes the variables and data interpretation. Section “Empirical analysis” presents the analysis of the results, discussing the baseline regression and robustness test results. Section “Further analysis” further examines the mechanisms and heterogeneity characteristics of how zombie firms impact labor mobility. Section “Conclusions” presents conclusions.

Literature review and theoretical analysis

Literature review

Research related to this paper can be mainly divided into two categories. One category of research mainly discusses the causes and impacts of zombie firms. Regarding the causes of zombie firms, evidence from developed countries suggests that during periods of economic downturn, banks engaging in zombie lending to cover up non-performing loans is a primary reason for the formation of zombie firms (Peek and Rosengren, 2005; Bruche and Llobet, 2014). In China, which is undergoing economic transition, the combination of fiscal decentralization and a promotion system that heavily emphasizes GDP as a key performance indicator provides local governments with strong incentives to intervene in the local economy (Zhou, 2007). Therefore, it is important not to overlook the impact of government intervention on the formation of zombie firms during periods of normal economic operation (Chang et al., 2021). An increasing number of studies have explored the economic implications of zombie firms, particularly their macroeconomic consequences. From a macroeconomic perspective, the persistent prevalence of zombie firms has been identified as a critical determinant contributing to Japan’s prolonged economic stagnation and the anemic recovery of the global economy following the 2008 financial crisis (Caballero et al., 2008; Hoshi and Kashyap, 2015). Recent empirical studies utilizing micro-level datasets from single-country and multinational contexts to rigorously examine the impacts of zombie firms have demonstrated that the persistence of these nonviable enterprises induces significant resource misallocation (Feng et al., 2022), thus causing various harms. These include impeding productivity growth (Kwon et al., 2015), crowding out the investment of normal firms (Tan et al., 2016) and employment (Xiao et al., 2019), reducing capacity utilization (Shen and Chen, 2017; Mao and Xu, 2024), suppressing the innovation efficiency of normal firms (Qiao et al., 2022), hindering industrial upgrading (Geng et al., 2021), and leading to environmental problems (Wu et al., 2023).

The second strand of literature examines the determinants of labor mobility, primarily unfolding along two analytical pathways. The first line of inquiry adopts a micro-individual perspective to analyze how personal and household characteristics influence labor mobility decisions. Representative factors include educational attainment (Brown and Souto-Otero, 2020) and gender disparities (Xie et al., 2022). The second pathway employs a macro-regional lens, emphasizing the role of socioeconomic and developmental attributes in shaping cross-regional labor flows (Liu et al., 2022; Zhang, 2022). Based on extant research, employment opportunities and income levels typically constitute pivotal factors in labor mobility. For instance, industrial relocation precipitates the movement of the labor force (Liu and Zhang, 2022). However, as labor demand structures evolve, migration considerations have become increasingly multidimensional. Non-economic welfare factors now play a growing role in destination selection, with regional amenities emerging as a critical focus in recent scholarship (Bryan and Morten, 2019). Notably, environmental degradation—particularly severe air pollution—has been shown to deter labor inflows (Liu and Yu, 2020; Chen et al., 2022). Conversely, enhanced public services encompassing transportation infrastructure, healthcare systems, and quality basic education demonstrate significant positive effects on attracting labor, especially high-skilled workers (Xia and Lu, 2015).

A review of existing literature reveals that while a substantial body of research has predominantly focused on the negative externality effects of zombie firms on economic and social systems, limited attention has been devoted to examining the interrelationship between zombie firms and the labor market. Particularly, there exists a notable paucity of scholarly investigation into the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility and its underlying mechanisms. This study addresses this research gap by adopting the lens of zombie enterprises to systematically investigate their influence on urban-level labor mobility patterns and the operational mechanisms involved. The research not only enriches our understanding of zombie firm dynamics but also provides novel perspectives and empirical evidence for identifying key determinants of labor mobility.

Theoretical analysis

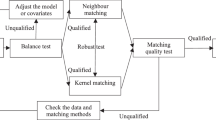

Building on the existing literature, this paper posits that zombie firms may affect inter-regional labor mobility by exacerbating industrial rigidity, obstructing new firm entry, and worsening environmental pollution, ultimately resulting in a lack of attractiveness to labor.

Firstly, the resource misallocation effect of zombie firms exacerbates the rigidity of regional industrial structures, thereby hindering labor inflows and promoting labor outflows. The continued subsidies and preferential allocation of credit resources by local governments and banks to zombie firms reduce the efficiency of local resource allocation (Kwon et al., 2015). On the one hand, normal firms struggle to obtain credit resources for investment and innovation activities, while zombie firms lack innovation capacity. In the long run, regions with a proliferation of zombie firms suffer from significant innovation deficiencies, characterized by insufficient technological advancement and severe resource misallocation, which hinders local industrial upgrading (Geng et al., 2021). Zombie firms are heavily concentrated in resource-based industries such as steel and coal (Huang and Chen, 2017), impeding the flow of labor and capital that should otherwise be directed to other industries. The widespread existence of zombie enterprises has curbed local industrial upgrading, hindered the development of local industrial diversification, and reduced employment opportunities for both local and migrant labor forces. This has led to the outflow of local labor and has also been unfavorable to the influx of migrant labor. On the other hand, local governments continue to provide subsidies and policy support to zombie firms in pursuit of economic growth and employment stability. The expansion of capacity by these low-capacity-utilization firms exacerbates regional overcapacity issues. As local economic growth becomes increasingly dependent on current industrial development patterns, a vicious cycle of “subsidizing zombie firms-overcapacity-economic growth dependence on current output-continuing to subsidize zombie firm production” emerges, intensifying the rigidity of regional industrial structures, further impeding local industrial upgrading, thus making it difficult to attract labor inflows. This paper refers to this mechanism as the “industrial structure rigidity effect”.

Secondly, the prolonged existence of zombie firms suppresses the entry and growth of new firms, negatively impacting local employment growth and making it difficult to attract labor inflows. The impact of zombie firms on new firm entry at the local level may be attributed to two main channels. On the one hand, the extensive presence of zombie firms is often a result of local government intervention in the market. Existing literature indicates that in regions with a high proportion of zombie firms, the cost for normal firms to access local credit resources is higher (Tan et al., 2016) and they face a greater tax burden (Li et al., 2018), creating high anticipated costs for potential market entrants. On the other hand, a conducive innovation environment fosters knowledge spillovers, allowing new firms to obtain the latest technologies and knowledge from neighboring firms and research institutions, thereby enhancing their innovation capabilities and competitiveness. Zombie firms, however, have lower innovation levels and disrupt the innovative output of normal firms in the region (Wang et al., 2018). This results in lower overall innovation levels in regions with a high proportion of zombie firms, leading to negative expectations about the future development of potential market entrants. Location selection is a crucial micro-level decision for firms. From the perspectives of anticipated costs and expected development, regions with a high proportion of zombie firms are less attractive to new firms. Relevant research suggests that areas and industries with a high proportion of zombie firms are more likely to create market entry barriers for new firms (Adalet McGowan et al., 2018). The reduction in the number of new entrants, which are key players in absorbing labor and generating employment, not only signifies a decline in local market vitality but also leads to a decrease in regional employment scale and new job opportunities, thereby hindering labor inflows. This paper refers to this mechanism as the “barrier to new firm entry effect”.

Thirdly, the continued capacity expansion by high-energy, high-emission zombie firms exacerbates regional environmental pollution, increasing local labor outflows. Industrial production activities, particularly those in heavy industries, are significant sources of regional environmental pollution. Zombie firms predominantly exist in high-consumption, high-pollution industries, where they not only maintain high levels of pollution emissions and significant excess capacity but also depress the capacity utilization rates of normal firms (Shen and Chen, 2017). Existing literature indicates that as the proportion of zombie firms increases, the pollution emissions of normal firms in the local market also rise (Wu, 2021; Chao et al., 2022), resulting in more severe local environmental pollution. Environmental pollution directly impacts human health and well-being. As ecological, environmental protection, and livability concerns increasingly become mainstream cultural values in modern society, the environmental pollution caused by the persistent presence of zombie firms is a significant factor affecting contemporary labor, especially young and highly skilled workers, in terms of long-term migration. Local environmental issues are crucial in determining labor employment location decisions. Research has shown that higher levels of local air pollution correlate with a lower probability of migrant workers seeking employment in that city (Yue et al., 2024). This paper refers to this mechanism as the “environmental pollution aggravation effect”.

Based on the above analysis, this paper constructs an analytical framework for zombie firms affecting labor mobility (Fig. 1), and empirically examines the impact of zombie firms on urban labor mobility and its mechanism.

Model setting and variable description

Econometric model design

Based on the previous analysis, this paper sets up the following model to examine the relationship between zombie firms and urban labor mobility:

In formula (1), \({\Delta{labor}}_{{ct}}\) denotes the amount of change in the labor migration rate in city c from period t-1 to period t. \(\overline{{{Zombie}}_{{ct}}}\) is the mean value of the share of zombie firms in city c from period t-1 to period t. \({X}_{{ct}}\) represents a series of control variables. \({\mu }_{c}\) and \({\nu }_{t}\) represent t city fixed effects and period fixed effects, respectively. \({\xi }_{{ct}}\) denotes the error term.

Variable description

Dependent variable

The dependent variable of this paper is net labor inflow \({\Delta l{abor}}_{{ct}}\), referring to Kirchberger (2021) and Chen et al. (2022), the net labor inflow to city c is measured by Eqs. (2) and (3).

where \({\Delta l{abor}}_{{ct}}\) is the first-order difference variable for the three five-year intervals of 2000–2005, 2005–2010, and 2010–2015. Considering that this paper focuses on the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility, only the population aged 16–64 is retained in the data sample for measuring net labor inflow. In Eq. (2), a nonlocal registered resident means that the labor force’s household registration location is outside the surveyed city.

Independent variable

The independent variable of this paper is the proportion of zombie firms at the urban level (\(\bar{{{Zombie}}_{{ct}}}\)). The core perspective of existing research on identifying zombie firms lies in identifying enterprises that are insolvent, have long-term losses, and borrow at below market interest rates (Caballero et al., 2008; Fukuda and Nakamura, 2011), following the approach of Shao et al. (2022), this paper primarily employs the modified FN-CHK method to identify zombie firms. This method allows us to estimate the proportion of zombie firms at the city level (Zombie) from 2000 to 2013. Based on this, the average proportion of zombie firms in the city is calculated for the periods 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2011–2013Footnote 3, yielding \(\overline{{Zombie}}\) The specific approach involves using firms’ current and long-term liabilities, as well as short-term and long-term interest rates, to calculate the minimum interest firms should pay. Then, the firms’ interest income is calculated to obtain the interest differential and actual profits, identifying firms with actual profits less than zero, a debt-to-asset ratio exceeding 50%, and increased debt compared to the previous period as zombie firms. After identifying zombie firms, the proportion of zombie firms in a city is measured by the share of total employment in zombie firms relative to total local employment. After estimating the proportion of zombie firms for each year, the average proportions for each period are calculated to obtain the average zombie firm proportions for the three periods. Additionally, robustness checks are conducted using alternative measures, including the share of total output \(\overline{{Zombie}1}\) and the share of total assets \(\overline{{Zombie}2}\) of zombie firms in the city.

Control variables

This paper controls for economic and demographic characterization variables at the urban level, respectively. Among them, the urban economic characteristic variables include the industrial structure and the level of foreign direct investment, which are measured by the proportion of the number of employees in the secondary industry (ind) and the logarithm of foreign investment (lnfdi), respectively. The demographic variables include the percentage of women, the percentage of ethnic minorities, the percentage of youth, and the percentage of unmarried people. Among them, the youth population is the population aged 15–24. Since zombie firms are closely related to economic activities, the initial year level of each period is used for each of the above variables, considering that they may be affected by zombie firms. Each of the above nominal variables is treated with the corresponding deflator.

Data sources

The data on urban labor force and regional population characteristics come from the microdata of population sampling surveys in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. The database provides information such as the population’s age, gender, educational attainment, household registration status, and the city where the survey is conducted. The original data required to calculate the proportion of urban zombie firms mainly come from the China Industrial Enterprise Database from 1998 to 2013, in which the interest rate data for each period comes from the central bank. The data required for the calculation of regional economic characteristic variables come from the China City Database.

The China Industrial Enterprise Database includes two types of enterprise information: basic information, including name of enterprise, address, number of employees, etc.; and financial information, including total output value, profit, assets, etc. The Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database has a very large sample size, covering all state-owned industrial enterprises and above-scale non-state-owned industrial enterprises, and can be used to measure the proportion of zombie firms at the city level in China. Referring to the practices of most existing related studies (Nie et al., 2012), the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database is processed to a certain extent. Specifically, samples that do not comply with general accounting standards, such as fixed assets greater than total assets, are deleted, samples with total industrial output value, total assets less than or equal to 0, and missing samples are deleted, and samples with employment less than 10 and sales output value less than 5 million yuan are deleted. In summary, this paper obtains data for 242 cities for a total of 3 periods. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistical information of each variable.

Empirical analysis

Benchmark regression

Table 2 presents the baseline regression results on the impact of zombie firms on urban labor mobility. Column (1) reports the regression results with city fixed effects and period fixed effects included. The empirical results show that without adding control variables, the regression coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms is negative and significant at the 5% level, indicating that zombie firms have a significant inhibitory effect on labor inflows into cities. Column (2) controls for city economic characteristics, and the results show that the absolute value of the regression coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms decreases but remains significantly negative. Column (3) controls for both city economic and demographic characteristics, and the regression coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms remains significantly negative.

The above results indicate that the presence of zombie firms significantly suppresses local labor inflows. This finding is broadly consistent with existing international research. Prior studies have primarily focused on the negative impact of zombie firms on employment growth, while few have examined whether zombie firms affect labor mobility. For example, Caballero et al. (2008) find that zombie lending in Japan suppressed employment expansion. Similarly, Adalet McGowan et al. (2018) show that regions with a higher share of zombie firms in OECD countries tend to exhibit weaker business dynamism and employment growth. While their analyses are largely based on firm-level micro evidence, our study takes a city-level perspective to explore the inhibiting effect of zombie firms on labor inflows. Local governments often subsidize zombie firms to stabilize growth and maintain employment. However, the baseline regression results suggest that the widespread presence of zombie firms leads to labor outflows from the region. One possible reason is that zombie firms have a long-term impact on the local industrial structure, their presence disrupts the efficient allocation of resources, hinders industrial upgrading, and negatively affects the local business environment. Moreover, as workers’ income levels rise, they demand higher standards of environmental quality and public services. In the short term, continuous subsidies to zombie firms might keep them “alive but stagnant,” potentially achieving the goal of stabilizing growth and maintaining employment. However, in the long term, these actions may be counterproductive.

Robustness test

Replacement of variables

In the benchmark regression analysis, this paper measures the share of zombie firms in the city by the share of zombie firms’ employment to total employment. Following Shao et al. (2022), the fixed asset share (\(\overline{{Zombie}1}\)) and total output value share (\(\overline{{Zombie}2}\)) of zombie firms are used as alternative measures. In addition, this paper measures the proportion of zombie enterprises in cities using data from Chinese industrial enterprises. The industries covered by this database constitute the main body of the secondary industry. To further explore the impact of the existence of zombie enterprises on labor mobility within industries, we replaced the numerator part of Eq. (2) with the number of non-local household registered laborers engaged in the secondary industry for the test. Table 3 presents the regression results after the variable substitution. The results in columns (1) and (2) show that, regardless of whether control variables are added, the regression coefficient of the proportion of zombie enterprises measured by the proportion of fixed assets of zombie enterprises is negative at the 10% significance level. The results in columns (3) and (4) also show that, with the addition of control variables, the significance level of the regression coefficient of the proportion of zombie enterprises measured by the total output value of zombie enterprises increases from 10 to 5%, and both are negative. The last two columns show the test results of the impact of zombie firms on the net inflow of labor in the secondary industry. The results show that the regression coefficient of the proportion of zombie enterprises is significantly negative. The above empirical results further verify that the inhibitory effect of zombie enterprises on the net inflow of labor is robust.

Sample processing

Given the existence of abnormal-indicator problems in the Chinese Industrial Enterprise data, which may result in errors or extreme values when calculating the proportion of zombie enterprises in cities, we respectively apply 1% winsorization (\(\overline{{Zombie}3}\)) and 1% truncation (\(\overline{{Zombie}4}\)) to the independent variable, and the regression results are shown in Table 4. Moreover, we simultaneously investigated the influence of the proportion of zombie enterprises, after undergoing winsorization and truncation, on the mobility of nonlocal-hukou labor in the secondary industry. The regression results can be found in columns (3) and (4). The result in column (1) reveals that the regression coefficient of the proportion of zombie enterprises after winsorization is negative at a 5% significance level. The result in column (2) indicates that the regression coefficient of the proportion of zombie enterprises after truncation is significantly negative. These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of zombie enterprises on the net inflow of labor is robust. The regression results of the last two columns show that the regression coefficients of the proportion of zombie enterprises after winsorization and truncation are both negative at a 5% significance level, demonstrating that the negative impact of zombie enterprises on the net inflow of labor in the secondary industry is equally robust.

Instrumental variable regression

In the above robustness test, this paper considers the potential errors in measuring key variables and the sample selection bias problem, adds control variables in the model, and controls for period fixed effects and city fixed effects. However, considering the potential reverse causality between zombie firms and labor mobility, for example, where labor outflows may prompt local governments to increase subsidies to firms to stabilize employment, thereby creating more zombie firms, which further results in a higher percentage of zombie firms in the city. To address potential endogeneity concerns, we construct two instrumental variables and employ an instrumental variable (IV) approach. First, following the methodologies of Xiao et al. (2019) and Shao et al. (2022), we construct the first instrument variable (\(\bar{{\rm{Z}}{\rm{ombie}}{\rm{IV}}1}\)) as the interaction between the share of SOE assets at the city level in 1998 and the national-level SOE debt-to-asset ratio from the year before each sample period. We then average this interaction across all sample periods. The city-level SOE asset share in 1998 is a predetermined variable and is thus uncorrelated with the contemporaneous error term of labor mobility, while it is highly correlated with the prevalence of zombie firms (Tan et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the national-level SOE debt ratio reflects macro-level time variation without cross-city differences and is unlikely to be directly related to city-level labor mobility, thus satisfying both the relevance and exclusion restrictions.

Second, we construct the second instrument variable (\(\overline{{\rm{Z}}{\rm{ombie}}{\rm{IV}}2}\)) as the interaction between the 1998 city-level SOE asset share and the national share of employment in the electricity, gas, and water supply sector at the beginning of each sample period. According to Huang and Chen (2017), the proportion of zombie firms in this sector is significantly higher than in other industries, making the sector’s employment share a relevant industry-level characteristic for the distribution of zombie firms. Since this variable is based on national-level employment data from the start of each period, it is unlikely to affect within-period city-level labor mobility directly and is thus plausibly exogenous. Table 5 shows the regression results of instrumental variables. The regression results show that regardless of whether control variables are introduced or not, the first-stage estimation results show that the regression coefficients of \(\bar{{\rm{Z}}{\rm{ombie}}{\rm{IV}}1}\) and \(\bar{{\rm{Z}}{\rm{ombie}}{\rm{IV}}2}\) are all positive at the 1% significance level and the Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistics are greater than the Stock-Yogo value of 15%, which makes the selection of this instrumental variable reasonable and effective by empirical guidelines. The results from columns (1) to (4) both show that the regression coefficients for the share of zombie firms are significantly negative.

Further analysis

Mechanism test

To test whether the presence of zombie firms leads to urban labor outflows through the effects of industrial structure rigidification, barriers to firm entry, worsening environmental pollution, and weakened social welfare, this paper establishes the following econometric model for empirical analysis:

In this model, Y represents the dependent variables, which include the degree of industrial structure rigidification in the city (Industry), the extent of barriers to firm entry (Hinder), the level of environmental pollution (Pollution), and the degree of social welfare (Security). Zombie denotes the proportion of zombie firms in the city, measured consistently with the method outlined in Section “Model setting and variable description”. M represents the control variables, which include the city’s level of economic development and foreign investment, measured by the logarithm of per capita GDP and the logarithm of foreign direct investment, respectively. Additionally, the model controls for city fixed effects and year fixed effects.

The dependent variables’ measurement methods and data sources are as follows: The degree of industrial structure rigidity in the city (Industry) is measured by the ratio of heavy industry output to total industrial output, with data sourced from the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database. A higher value of Industry indicates a more severe level of industrial structure rigidification in the city. The logarithm of the number of registered industrial and commercial enterprises in each city per year measures the extent of barriers to firm entry (Hinder). These data are obtained through web scraping from the Aiqicha website. A lower value of Hinder indicates higher barriers to firm entry. The logarithm of PM2.5 levels measures environmental pollution (Pollution). The PM2.5 data for cities is sourced from the Dalhousie Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group’s PM2.5 gridded data, and the annual average PM2.5 concentration data for cities from 2000 to 2013 uses ArcGIS technology. A higher level of Pollution indicates more severe environmental pollution in the city. The control variable data are sourced from the China City Database.

Since the proportion of zombie firms in cities from 2000 to 2013 can be measured using the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database, the sample period for the mechanism analysis covers 2000–2013. Additionally, due to the inconsistency in the number of sample cities used to measure the various effects of zombie firms, and to minimize potential bias from city selection, we conduct regression analyses using the full sample and a matched sample that aligns with the cities in the baseline regression.

Firstly, we examine the effect of zombie firms on the rigidity of the industrial structure. Column (1) of Table 6 reports the full sample regression results, showing that the coefficient of the proportion of zombie firms in cities is significantly positive. This indicates that as the proportion of zombie firms increases, the share of heavy industry output in total industrial output rises, making it increasingly difficult for cities to upgrade their industries, thereby leading to a more severe rigidity of the industrial structure. Zombie firms occupy substantial local credit resources, and their inefficient productivity and “vampiric” nature hinder the effective allocation of factor resources, suppressing local industrial upgrading. Moreover, the dependence of local economic growth on existing industries further exacerbates the rigidification of the city’s industrial structure, ultimately leading to a net outflow of labor. Geng et al. (2021), based on data from China, also found that the presence of zombie firms leads to resource misallocation and suppresses innovation among normal firms, thereby hindering industrial upgrading. Similarly, Rai et al. (2025), using data from Indian firms, argued that an increase in the proportion of zombie firms within an industry hampers the upgrading of normal firms through channels such as the reduction of productivity and the weakening of innovation capabilities. Column (2) of Table 6 reports the regression results using the matched sample from the baseline analysis, which also shows that the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms remains significantly positive, confirming the impact of zombie firms on the rigidity of the urban industrial structure.

Secondly, addressing the impact of barriers to enterprise entry, Column (3) of Table 6 reports the full sample regression results. The coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms in cities is significantly negative. This indicates that the widespread presence of zombie firms leads to severe misallocation of local credit resources, disrupting the local business environment and hindering the entry of new firms into the market. The proliferation of zombie firms significantly increases operating costs for normal firms and has a notable suppressive effect on the enhancement of the city’s innovation level. This undermines the positive expectations of potential market entrants regarding their future development, thereby affecting their decision to enter the local market. Some studies have reached similar conclusions. Caballero et al. (2008) and Adalet McGowan et al. (2018) argue that one of the serious consequences of zombie firms is market distortion, which sacrifices more productive potential firms while keeping inefficient ones. This, in turn, clearly hampers the entry of new firms and is detrimental to their growth. As local governments not only provide direct subsidies to zombie firms but also support them through various policies, the difficulty in phasing out zombie firms leads to their monopolistic characteristics. This further deters new firms from entering the market, making it challenging to create additional employment opportunities and resulting in a significant negative impact on net labor inflow. Column (4) of Table 6 reports the results for the matched sample, where the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms remains significantly negative, further validating that the proliferation of zombie firms creates barriers to new firm entry.

Thirdly, regarding the effect of increased environmental pollution, Column (5) of Table 6 presents the full sample regression results. The results show that the presence of zombie firms significantly exacerbates air pollution levels in cities. Zombie firms are prevalent in high-pollution, high-emission industries and suffer from low capacity utilization, leading to overcapacity and substantial pollutant emissions. Mashwani et al. (2024), using data from listed companies across multiple countries, find that the environmental and social responsibility performance of zombie firms is significantly lower than that of non-zombie firms. Wu (2021), based on a sample of Chinese enterprises, similarly demonstrate that the misallocation of credit resources to zombie firms results in insufficient green innovation among normal firms and reduced investment in waste treatment and purification equipment, further increasing pollutant emissions by these normal enterprises. As a result, the concentration of zombie firms further exacerbates local environmental pollution, which not only deters labor inflow but also compels more people to leave in search of new cities for work and living. Column (6) of Table 6 provides the results for the matched sample, which further confirms that the presence of zombie firms worsens local environmental pollution.

Heterogeneity analysis

In the benchmark regression analysis, this study examines the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility. Considering that zombie firms may have heterogeneous effects on labor mobility across different skill levels and age groups, the numerator in Eq. (2) is first replaced with the number of high school graduates and above and those with less than a high school education. Subsequently, Eq. (3) is used to calculate the net inflow of high-skill labor (highskill) and low-skill labor (lowskill) for each city. By substituting these two variables for the dependent variable in the benchmark regression, the study assesses the impact of zombie firms on the mobility of different skill levels of labor. Column (1) of Table 7 shows that without control variables, the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms is significantly negative at the 10% level, indicating that the presence of zombie firms is detrimental to the inflow of high-skill labor. Column (2) shows that after including control variables, the coefficient remains negative but is no longer significant. The results in the subsequent columns demonstrate that, regardless of the inclusion of control variables, the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms is significantly negative at the 5% level.

These results suggest that, compared to high-skill labor, zombie firms have a more pronounced suppressive effect on the inflow of low-skill labor. On the one hand, Xiao et al. (2019), using the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database from 1998 to 2013 for research, found that although zombie firms can maintain a certain level of employment themselves, they significantly inhibit the employment growth of normal firms. Most of the jobs in industrial enterprises are held by low-skilled labor. Therefore, this may lead to the manifestation of zombie firms’ inhibitory effect on the inflow of low-skilled labor. This result is consistent with the findings of Cheung and Imai (2024), who demonstrate that, although zombie loans in Japan’s construction and real estate sectors somewhat protect low-skilled labor employment in the construction industry, they have a significant negative impact on employment in other low-skilled sectors. On the other hand, when classifying labor skills, high school education is often used as the dividing line. The time scope of the research sample in this paper is from 2000 to 2015. Using education as a measure of labor skills, within the scope of the research sample of this paper, most of the labor force in China is low-skilled, and the proportion of high-skilled labor is relatively low. In cities with a large number of zombie firms, the inflow of high-skilled labor was originally low. As the number of zombie firms increases, the change in the inflow of high-skilled labor may be weak. Thus, it appears that zombie firms have no significant impact on the inflow of high-skilled labor.

Next, we examine zombie firms’ impact on labor inflow across different age groups. In this analysis, the numerator in Eq. (2) is replaced with the population aged 16–40 and 41–64, respectively. Equation (3) is then used to calculate the net inflow of younger and middle-aged labor (age 16–40) and the net inflow of middle-aged and older labor (age 41–64). By substituting these variables into the benchmark regression as the dependent variable, we can assess zombie firms’ impact on the net labor inflow across different age groups. The first two columns of Table 8 present the impact of zombie firms on the net inflow of younger and middle-aged labor. The results indicate that the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms is significantly negative at the 1% level, suggesting that the presence of zombie firms significantly suppresses the inflow of younger and middle-aged labor. The last two columns show the results for the net inflow of older labor, where the coefficient for the proportion of zombie firms is not significant.

These results suggest that the proliferation of zombie firms significantly hinders the inflow of younger and middle-aged labor. Statistically, the migration rate of younger labor is notably higher than that of older labor (Zhou, 2023), indicating a stronger willingness among younger individuals to migrate for better development prospects and higher income. Additionally, generally have higher demands for the livability and comfort of their destination compared to older generations. However, the substantial presence of zombie firms not only obstructs the upgrading of urban industrial structures but also limits the availability of diverse employment opportunities, which is detrimental to attracting younger and middle-aged labor. Research from China’s northeastern region highlights that one significant reason for the loss of young graduates is the mismatch between local industrial structures and labor skills (Zhang and Gu, 2018). Moreover, the large number of zombie firms can also impede improvements in urban air quality and public service levels, severely affecting the city’s livability and comfort, and thereby suppressing the migration of younger labor.

Conclusions

Labor, as the most critical factor of production, plays a crucial role in urban and regional economic growth. With the ongoing intensification of population aging, recent years have seen escalating competition among Chinese cities to attract talent. This phenomenon reflects the local government’s efforts to respond to pressures from industrial transformation and secure future development opportunities. However, the large presence of zombie firms in many Chinese cities negatively affects local economic and social development. It profoundly impacts the cities’ attractiveness and competitiveness in terms of labor.

This study utilizes microdata from population censuses (2000–2015) and the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database (1998–2013) to empirically examine the effects and mechanisms through which zombie firms influence labor mobility at the urban level. The research finds that the substantial presence of zombie firms significantly suppresses labor inflow into cities. This result remains robust after a series of robustness checks, including alternative measures of the proportion of zombie firms, sample adjustments, and instrumental variable regressions, confirming that zombie firms significantly cause labor outflow from cities. The mechanism analysis reveals that industrial structure, barriers to new entry, and environmental quality are three key channels through which zombie firms affect labor mobility. The proliferation of zombie firms leads to slower industrial upgrading, obstacles to new firm entry, and deteriorated environmental quality, all of which reduce the willingness of nonlocal labor to move to these cities and further accelerate local labor outflow. The heterogeneity analysis shows that low-skilled and younger and middle-aged laborers are more significantly affected by the negative impacts of zombie firms.

In summary, the main contribution of this paper is to study the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility in the process of urban industrial development from the perspective of zombie firms. This research expands the frontier of studies on zombie firms and labor markets, providing valuable policy insights for enhancing the attractiveness of urban labor markets through optimized zombie firms disposal policies.

Firstly, the long-term presence of zombie firms in urban industrial and economic systems is a significant factor in diminishing urban attractiveness and causing labor outflow. Cities with a high proportion of zombie firms should intensify efforts to address these firms, respecting market principles and allowing market mechanisms to play a decisive role in resolving zombie firm issues. Decisions regarding the survival or exit of zombie firms should be determined by the market rather than imposed through administrative intervention. Market-oriented reforms should be deepened to force inefficient firms out of the market, thereby reducing the negative impact of zombie firms and enhancing the city’s appeal and competitiveness for labor.

Secondly, the effects of zombie firms on industrial structure rigidity, barriers to new firm entry, environmental pollution aggravation, and weakened social welfare significantly constrain urban labor attraction. Urban governments should accelerate the clearance of zombie firms while aligning with local resource endowments and industrial conditions to foster emerging industries, promote industrial diversification and structural upgrading, and break free from reliance on traditional overcapacity industries and zombie firms. This will create diverse industrial pathways for labor inflow. Additionally, governments should cease financial support to inefficient and ineffective firms, deepen administrative reforms to facilitate the free flow of factors such as credit and land under market mechanisms and optimize resource allocation efficiency. This will create favorable conditions for the establishment, entry, and growth of new firms and provide more high-quality employment opportunities for labor.

Then, this study indicates that zombie firms exacerbate urban environmental pollution, hinder labor inflow, and accelerate labor outflow. Governments should use the clearance of zombie firms as a lever for promoting green transformation and sustainable development. For firms with severe direct and indirect pollution, closure should be considered even if traditional indicators like debt-to-asset ratios have not yet met liquidation standards. Urban governments should prioritize environmental protection in their development strategies, encourage investments in less environmentally harmful industries, build a positive urban image, stabilize business and labor expectations, and reduce the adverse impact of zombie firms on job opportunities.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the impact of zombie firms on labor mobility, but it does have some limitations, primarily related to the research data. Due to data constraints, the study only covered up to 2015, and the data was not continuous. Improvements in data structure could potentially yield more meaningful conclusions. This research offers a novel perspective on the relationship between zombie firms and labor, particularly through its findings in the heterogeneity analysis. Notably, the study reveals that zombie firms significantly suppress the inflow of low-skilled and younger and middle-aged labor. From this perspective, zombie firms may exacerbate regional labor market polarization. Future research could further explore this aspect.

Data availability

The data, China Industrial Enterprises Database, and Micro population data, which support the findings of this study, are available from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The specific sources of the remaining data have been described in detail in Data sources section and Mechanism test section. The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The original data are from the sixth and seventh census, and the data in this paper are calculated by the author. The labor force refers to the population aged 15–64.

We followed the approach of most current literature using the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database for research, and used the data from 1998 to 2013 for our study. Considering the possible decline in the accuracy of the 2010 data (Chen, 2018), we did not include the 2010 data samples.

References

Adalet McGowan M, Andrews D, Millot V (2018) The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries. Econ Policy 33(96):685–736

Brown P, Souto-Otero M (2020) The end of the Credential Society? An analysis of the relationship between education and the labour market using big data. J Educ Policy 35(1):95–118

Bruche M, Llobet G (2014) Preventing zombie lending. Rev Financ Stud 27(3):923–956

Bryan G, Morten M (2019) The aggregate productivity effects of internal migration: evidence from Indonesia. J Polit Econ 127(5):2229–2268

Caballero RJ, Hoshi T, Kashyap AK (2008) Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. Am Econ Rev 98(5):1943–1977

Chang Q, Zhou Y, Liu G (2021) How does government intervention affect the formation of zombie firms? Econ Model 2021:768–779

Chao S, Guo L, Sun S (2022) Zombie problem: normal firms’ wastewater pollution. J Clean Prod 330:129893

Chen YY, Zhang J, Zhou YH (2022) Industrial robots and spatial allocation of labor. Econ Res J 57(01):172–188

Chen L(2018) Re-exploring the usage of Chinaas industrial enterprise database Econ Rev 6:140–153

Cheung JKW, Imai M (2024) Zombie lending, labor hoarding, and local industry growth. Jpn World Econ 71:101266

Feng L, Lang H, Pei T (2022) Zombie firms and corporate savings: evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Int Rev Econ Financ 79:551–564

Fukuda S, Nakamura J (2011) Why did ‘zombie’ firms recover in Japan? World Econ 34(7):1124–1137

Geng Y, Liu W, Wu Y (2021) How do zombie firms affect China’s industrial upgrading? Econ Model 97:79–94

Hoshi T, Kashyap AK (2015) Will the US and Europe avoid a lost decade? Lessons from Japan’s postcrisis experience. IMF Econ Rev 63(1):110–163

Hu S, Jia N (2025) The impact of the “full liberalization of household registration” policy on the free migration of rural labor. China Econ Rev 89:102330

Huang SQ, Chen Y (2017) The distribution features and classified disposition of China’s zombie firms. China Ind Econ No.348(03):24–43

Kirchberger M (2021) Measuring internal migration. Reg Sci Urban Econ 91:103714

Kwon HU, Narita F, Narita M (2015) Resource reallocation and zombie lending in Japan in the 1990s. Rev Econ Dyn 18(4):709–732

Li XC, Lu JK, Jin XR (2018) Zombie firms and tax distortion. J Manag World 34(04):127–139

Liu Y, Zhang X (2022) Does labor mobility follow the inter-regional transfer of labor-intensive manufacturing? The spatial choices of China’s migrant workers. Habitat Int 124:102559

Liu Z, Yu L (2020) Stay or leave? The role of air pollution in urban migration choices. Ecol Econ 177:106780

Liu Z, Qi H, Liu S (2022) Labor shrinkage and its driving forces in China from 1990 to 2015: a geographical analysis. Appl Spat Anal Policy 15(2):339–3

Mao Q, Xu J (2024) Zombie firms, misallocation and manufacturing capacity utilization rate: evidence from China. Econ Transit Institutional Change 32(2):641–682

Mashwani AI, Mushtaq R, Gull AA et al. (2024) The walking dead: are Zombie firms environmentally and socially responsible? A global perspective. J Environ Manag 355:120499

Nie H, Jiang T, Yang R (2012) A review and reflection on the use and abuse of Chinese industrial enterprises database. World Econ 5:142–158

Nie HH, Jiang T, Zhang YX (2016) The current situation, causes and countermeasures of zombie firms in China. Macroecon Manag 9:63–68+88

Peek J, Rosengren ES (2005) Unnatural selection: perverse incentives and the misallocation of credit in Japan. Am Econ Rev 95(4):1144–1166

Peng GH (2015) The matching of skills to tasks, labor migration and Chinese regional income disparity. Econ Res J 50(01):99–110

Qi L, Chen QY, Wang RY (2015) Household registration reform, labor mobility and optimization of the urban hierarchy. Soc Sci China 36(2):130–151

Qiao X, Song L, Fan X (2022) How do zombie firms affect innovation: from the perspective of credit resources distortion. Asian‐Pac Econ Lit 36(1):67–87

Qiao XL, Song L (2022) Zombie firms, labor resource misallocation, and macro-efficiency losses: based on the perspective of labor resource flow among firms. Ind Econ Res 2:71–84

Rai AK, Sharma R, Arora H (2025) Zombie firms and their congestion effects: exploration of industrial upgradation and innovation. Int Rev Appl Econ 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2025.2468656

Shao S, Yin JY, Fan MT et al. (2022) Zombie firms and low-carbon transformation development: a perspective on carbon emission. J Quant Technol Econ 39(10):89–108

Shen G, Chen B (2017) Zombie firms and over-capacity in Chinese manufacturing. China Econ Rev 44:327–342

Sheng L (2022) Towards high-quality economic development: research on optimizing the governance path of “zombie firms”. Shanghai People’s Publishing House, China, p 74–95

Tan Y, Huang Y, Woo WT (2016) Zombie firms and the crowding-out of private investment in China. Asian Econ Pap 15(3):32–55

Wang YQ, Li W, Dai Y (2018) How do zombie firms affect innovation?—Evidence from China’s industrial firms. Econ Res J 53(11):99–114

Wang JY, Jia N (2021) Labor attraction effect of income premium in Megalopolis: based on the empirical study of three Megalopolis in China and Bos Wash in the United States. Chin J Popul Sci 6:27–41+126–127

Wu Q, Chang S, Bai C et al. (2023) How do zombie enterprises hinder climate change action plans in China? Energy Econ 124:106854

Wu QY (2021) How do zombie firms affect pollution emissions: evidence from China’s micro environment data. China Popul Resour Environ 31(11):34–47

Xia YR, Lu M (2015) “Mencius’s Mother’s Three Moves” between cities: an empirical study on the impact of public services onlabor flow. J Manag World 10:78–90

Xiao XZ, Zhang WG, Z Y (2019) Zombie firms and employment growth: protection or crowding? J Manag World 35(08):69–83

Xie F, Liu S, Xu D (2022) Gender difference in time-use of off-farm employment in rural Sichuan, China. J Rural Stud 93:487–495

Yue Q, Song Y, Zhang M et al. (2024) The impact of air pollution on employment location choice: evidence from China’s migrant population. Environ Impact Assess Rev 105:107411

Zhang JY, Gu Y (2018) An analysis on the loss and cause of highly-educated talent in Northeast China—based on the graduate employment data of Jilin University from 2013 to 2017 Popul J 40(05):55–65

Zhang X (2022) Linking people’s mobility and place livability: implications for rural communities. Econ Dev Q 36(3):149–159

Zhou H (2023) The pattern of age-specific migration rate of floating population and its changes in China. J East China Norm Univ 55(01):185-201+206

Zhou LA (2007) Governing Chinaas local officials: an analysis of promotion tournament model. Econ Res J 7:36–50

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shuguang Program (grant number: 20SG56); Eastern Talent Plan Youth Program; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (graduate student project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS: funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review & editing; XZ: funding acquisition, writing—original draft, data curation, methodology; NH: supervision, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This study does not contain any studies with human participants by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheng, L., Zhang, X. & Hong, N. How do zombie firms affect labor mobility: city-level empirical evidence from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1350 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05711-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05711-0

This article is cited by

-

The Impact of Clean Energy on Population Outflow from Shrinking City: Evidence from West-East Gas Pipeline in China

Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2025)