Abstract

This paper investigates the role of university life satisfaction on students’ positive word-of-mouth and the moderating influence of perceived education quality and university brand knowledge. Participants included first-year students from a central Taiwan university enrolled for at least 6 months. Using purposive sampling, 816 valid responses were collected via an online survey, achieving a 30.93% response rate. Findings reveal that higher life satisfaction enhances positive word-of-mouth, education quality strengthens this effect, and brand knowledge weakens it. Finally, the study offers practical implications and suggestions for future research based on its findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The success and reputation of higher education institutions rely on factors like the quality of their graduates, the number of students who return for further studies (Vukasovič, 2015), and the positive word-of-mouth shared with potential students (Cao et al., 2019). Choosing a university is an important decision for prospective students, one that requires careful evaluation of various factors (Le et al., 2020). Previous research has examined determinants of students’ university choice (e.g., Drewes and Michael, 2006; Skinner, 2019; Weisser, 2020) and explored positive word-of-mouth in higher education from both current students and alumni, including its antecedents such as service quality, brand identification, and satisfaction (e.g., Aslan and Aslan, 2025; Dandis et al., 2022; Rasheed and Rashid, 2024; Schlesinger et al., 2023; Zeqiri et al., 2023) as well as its consequences (e.g., Amani, 2022; Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023).

While prior studies have often investigated word-of-mouth as an outcome of service quality dimensions or brand-related factors, and have examined satisfaction primarily as a mediator in these relationships (e.g., Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023; Rasheed and Rashid, 2024), limited attention has been paid to university life satisfaction as a holistic, student-centered construct that captures the overall quality of students’ campus experience beyond service touchpoints. Life satisfaction encompasses broader cognitive and evaluative judgments about one’s overall university experience, including academic, social, and personal well-being dimensions (Raza et al., 2020; Reeve and Lee, 2019), rather than satisfaction with specific services or programs.

This distinction is important because life satisfaction reflects the integration of both academic and non-academic experiences, which may offer unique explanatory power for students’ propensity to engage in positive word-of-mouth beyond what service-specific satisfaction measures capture. Accordingly, this work addresses a gap in the literature by examining the direct relationship between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth intention, an area that, despite extensive research on satisfaction and word-of-mouth, remains underexplored when life satisfaction is conceptualized and measured as a global indicator of students’ university experience. This focus shapes the basis of the first research question.

Education is vital for promoting national development and social progress (Akareem and Hossain, 2016; Chankseliani et al., 2021). The significance of education quality in shaping students’ post-graduation success is widely recognized across different fields, regardless of their chosen careers (Scott and Guan, 2023). For this reason, universities need to uphold and maintain high standards in the educational environment, following established quality indicators in higher education (Aldhobaib, 2024; Žalėnienė and Pereira, 2021). This study’s second research question examines whether perceived education quality acts as a moderating role in the association between students’ satisfaction with university life and their likelihood of sharing positive word-of-mouth about the organization.

Recent studies reinforce the idea that brand knowledge, encompassing a customer’s awareness and understanding of a brand, significantly influences consumer behavior (Elsharnouby et al., 2021; Baruönü, 2025). Within the university setting, brand knowledge can impact how students gather and interpret information about a school, ultimately influencing their opinions of it (Balaji et al., 2016). This study’s third research question examines whether brand knowledge is an important factor in the link between students’ satisfaction with university life and their positive word-of-mouth.

In summary, this paper aims to investigate whether students’ satisfaction with university life affects their likelihood of sharing positive word-of-mouth about the university, while also examining how perceived education quality and university brand knowledge might moderate this relationship. On the theoretical side, this paper hopes to fill a gap in the existing literature on university management. Practically, the findings are expected to give universities useful insights for developing policies related to academic affairs, student services, admissions, public relations, and campus environment maintenance.

Literature review

Positive word-of-mouth

Word-of-mouth is the way information is shared from one individual to another (Frenzen and Nakamoto, 1993). In higher education, word-of-mouth refers to informal, face-to-face communication that isn’t influenced by commercial motives (Chen, 2016). For students, it serves as a valuable source of information for prospective students deciding where to attend (Le et al., 2020). Interestingly, while word-of-mouth doesn’t always aim to influence others, shared reviews inevitably have an impact, whether positive or negative (Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023).

This study looks at word-of-mouth from the perspective of current students, defining positive word-of-mouth as students sharing favorable opinions about their university. It’s worth mentioning that there has been limited research on positive word-of-mouth specifically from the perspective of current students or alumni (e.g., Amani, 2022; Dandis et al., 2022; Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023; Gallarza et al., 2020; Greenacre et al., 2014; Heffernan et al., 2018; Le et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Schlesinger et al., 2023; Zeqiri et al., 2023). As summarized in Table 1, prior studies on word-of-mouth in higher education have examined both its antecedents and consequences, with antecedents receiving relatively greater attention.

A review of the above literature reveals that, in the context of higher education, word-of-mouth plays a crucial role in influencing students’ university choice, study experience, and subsequent behavioral intentions. Many studies indicate a close relationship between service quality (including various aspects of campus services, accommodation, and healthcare services) and student satisfaction, with satisfaction often serving as an important mediator of word-of-mouth (Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023; Dandis et al., 2022; Zeqiri et al., 2023). During the university selection process, students tend to rely on word-of-mouth information from their interpersonal networks to reduce uncertainty and strengthen decision-making confidence (Le et al., 2020; Sipilä et al., 2017). In addition, factors such as brand image, course experience, and loyalty can enhance students’ positive emotions and perceived value, thereby encouraging them to recommend the institution to others (Chen, 2016; Rehman et al., 2022). Some studies further highlight that perceived usefulness, entrepreneurship education, and the quality of international education are specific dimensions that can influence students’ choices and attitudes through word-of-mouth (Amani, 2022; Ismail, 2025; Stribbell and Duangekanong, 2022; Rabah et al., 2024). Distinct from prior research, this paper suggests that students’ satisfaction with university life is an important factor driving positive word-of-mouth.

University life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth

Life satisfaction reflects how a person feels about their life as a whole (Diener and Diener, 1995), encompassing feelings of fulfillment, happiness, and belonging, as well as a sense of achievement and purpose, and the absence of anxiety or worry (Kirmani et al., 2015; Liu and Wang 2024). Within the higher education settings, student satisfaction has long been recognized as a critical outcome variable, with numerous studies examining its direct relationship with education quality (e.g., Singh and Jasial, 2021; Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023; Rasheed and Rashid, 2024). These studies often position satisfaction as a mediator between service or education quality and subsequent outcomes, such as loyalty or positive word-of-mouth.

In contrast, the present study does not treat education quality as a direct antecedent of satisfaction but instead examines it as a potential moderator in the link between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth. While the results confirm that education quality significantly influences satisfaction, the focus here is on understanding whether perceptions of education quality strengthen or weaken the effect of overall university life satisfaction on students’ willingness to share positive word-of-mouth. This approach offers an alternative perspective to the dominant direct-effect models in prior research.

Enhancing student satisfaction is beneficial for both universities and students (Lee et al., 2020). Satisfied students often perform better academically and tend to remain loyal to their university after graduation (Parahoo et al., 2013; Wilkins et al., 2016). In summary, this paper suggests that when students experience high satisfaction with university life, they are more inclined to be loyal advocates for their university during their studies.

Social exchange theory (SET), first proposed by Homans (1958) and later elaborated by Blau (1964), provides a social psychological and sociological framework for understanding social behavior as the exchange of tangible and intangible resources, such as approval, status, and information, between individuals or groups. The theory posits that when one party offers benefits to another, the recipient is generally inclined to respond with positive reciprocity (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Within such exchanges, individuals develop a sense of obligation to return the socio-emotional resources they have received, which fosters mutual trust, a long-term orientation, and sustained cooperative relationships (Kuvaas et al., 2020).

Applied to the higher education context, SET suggests that students who are highly satisfied with their university life perceive that they have received substantial socio-emotional and developmental resources from the institution, including quality education, supportive faculty, enriching campus activities, and valuable peer networks. In line with SET, this perceived receipt of benefits generates a psychological obligation to reciprocate toward the provider of those benefits—in this case, the university. One way students can fulfill this obligation is by engaging in positive word-of-mouth, particularly by promoting their university to high school students who are potential applicants. Such advocacy represents a non-material form of repayment, which helps maintain and strengthen the social exchange relationship between students and their university.

From the SET perspective, university life satisfaction is not only an outcome of positive experiences but also a driver of pro-university behaviors. When students perceive that their university experience has provided them with significant value, they are more inclined to reciprocate through reputational support directed at prospective students, thereby enhancing the institution’s image and attractiveness to future applicants. Based on this discussion, this work proposes the following hypothesis:

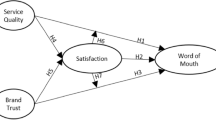

Hypothesis 1: The higher the university life satisfaction of students, the more positive their word-of-mouth about the university.

Moderating role of perceived education quality

Higher education institutions need to focus not only on producing qualified graduates but also on how students perceive the quality of their education (Calvo-Porral et al., 2013). Educational quality refers to an institution’s ability to produce graduates who can meet society’s demands and expectations in a highly competitive global market (Scott and Guan, 2023). In the university setting, this includes students’ evaluations of their courses, overall experiences, and whether they feel they’re getting good value for their money (Calvo-Porral et al., 2013). Oldfield and Baron (2000) highlighted the significance of paying attention to students’ views on educational quality, so this study suggests that perceived educational quality should be evaluated from the students’ perspective.

From the perspective of SET (Homans, 1958; Blau, 1964), students’ satisfaction with university life can be understood as the result of receiving valuable socio-emotional and developmental resources from their institution. When perceived education quality is high, students attribute a greater share of their positive experiences to the university’s provision of these resources (Mendoza-Villafaina and López-Mosquera, 2024), such as effective teaching, relevant curricula, and supportive learning environments, which strengthens their felt obligation to reciprocate. Empirical evidence shows that higher education service quality significantly enhances satisfaction and encourages loyalty behaviors such as positive word-of-mouth (Zeqiri et al., 2023). One way this reciprocity is expressed is through positive word-of-mouth, particularly toward high school students who are potential applicants. In this high-quality context, satisfaction is strongly tied to the institution’s consistent delivery of benefits, reinforcing the exchange relationship and amplifying students’ willingness to advocate for the university.

In contrast, when perceived education quality is low, students may still report satisfaction due to other factors such as peer support or extracurricular experiences, which have been shown to foster well-being and engagement independent of formal academic quality (Wong and Chapman, 2023). However, in such cases, the source of satisfaction is less clearly linked to the institution’s educational offerings, which weakens the perceived exchange relationship. As a result, the motivational pull to reciprocate with enthusiastic and confident positive word-of-mouth is reduced. Therefore, perceived education quality can strengthen or weaken the extent to which university life satisfaction translates into positive word-of-mouth. In line with SET, high perceived quality reinforces the reciprocity mechanism by making the institution the clear source of valued benefits, while low perceived quality dilutes this link by shifting the credit for satisfaction away from the institution. Drawing from this discussion, the paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived education quality positively moderates the relationship between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth, such that the relationship is stronger when perceived education quality is high rather than low.

Moderating role of university brand knowledge

Brand knowledge refers to the impressions and mental connections that consumers have about a brand in their minds or memory (Keller, 2003). It includes both descriptive and evaluative information tied to the brand, made up of individual impressions stored in consumers’ memory (Alimen and Guldem, 2010). In other words, brand knowledge is simply what consumers know and think about a particular brand (Baker et al., 2014). For universities, brand knowledge means how aware students are of the university’s values, communication methods, and the benefits it offers (Balaji et al., 2016).

From the perspective of SET (Homans, 1958; Blau, 1964), current university students with high brand knowledge have a clearer and stronger understanding of the benefits their institution provides, such as its academic reputation, program quality, and unique learning opportunities. This clarity enables them to attribute their positive experiences directly to the university, reinforcing the perceived exchange relationship. In turn, they feel a stronger obligation to reciprocate by advocating for the institution through positive word-of-mouth, particularly when communicating with high school students who are potential applicants. In this high brand knowledge context, satisfaction with university life is strongly tied to identifiable and valued institutional benefits, such as opportunities for capacity development (e.g., acquiring general and professional competences) and well-maintained hygiene factors like teaching methods, faculty quality, curriculum management, and facilities (De-Juan-Vigaray et al., 2024). When these elements are consistently delivered, they not only strengthen students’ positive evaluations but also foster a sense of loyalty, making their recommendations more confident, specific, and persuasive.

Conversely, current university students with low brand knowledge may still feel satisfied with their university life due to strong personal growth and social integration. Factors like a supportive learning environment, meaningful engagement with peers and faculty, and involvement in extracurricular activities contribute substantially to their satisfaction (Li et al., 2025). However, this weaker brand understanding dilutes the perceived reciprocity toward the institution, reducing the strength of the satisfaction-advocacy link. Although such students may still share positive word-of-mouth, their endorsements are less likely to focus on the institution’s distinctive value and therefore carry less persuasive power.

Therefore, in line with SET, university brand knowledge among current students can enhance or weaken the extent to which satisfaction with university life translates into positive word-of-mouth by influencing how clearly students attribute their satisfaction to the institution itself. Based on this discussion, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Hypothesis 3: University brand knowledge negatively moderates the relationship between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth, such that the relationship is stronger when university brand knowledge is low rather than high.

Drawing on existing research and formulated hypotheses, this work introduces the proposed research framework, displayed in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Sample

The sample for this study consisted of first-year undergraduate students, including first-year students in the 5-year junior college program, from a private university in central Taiwan who had been enrolled for at least 6 months at the time of the survey. First-year students were selected because they tend to maintain closer connections with high school peers, making them more likely to engage in positive word-of-mouth toward prospective students within their immediate social networks. In contrast, students in their second year or above are less likely to know high school students who are only two grades below them. By the 6-month mark, these first-year students had completed one academic semester, participated in courses and campus activities, and interacted with faculty, peers, and administrative services, providing sufficient experience to evaluate the university’s education quality and related aspects. Using purposive sampling, the university’s Institutional Research Office identified eligible respondents based on the inclusion criteria and distributed an online survey via Google Forms. A total of 2638 questionnaires were sent to these respondents, and all responses were collected through the same system.

The choice of Taiwan as the study location is particularly relevant due to its unique educational and cultural context. Taiwan’s higher education system is distinct, with private universities placing increasing emphasis on enhancing student satisfaction and engagement to remain competitive in a highly dynamic education market. The findings from this study will contribute valuable insights to the development of targeted support systems, such as academic advising, career counseling, and extracurricular activities, aimed at improving students’ overall university experience, particularly within private institutions.

The purposive sampling method was chosen to obtain data from participants with sufficient exposure to university life to provide meaningful insights into the research questions. Although the data were collected via an online questionnaire, which is a tool commonly associated with probability-based surveys, the sampling frame was intentionally restricted to participants meeting the inclusion criteria. This approach aligns with purposive sampling principles.

Before distributing the official questionnaire, actions were taken to minimize social desirability bias, following the approach recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2012). First, respondents were notified that the survey was purely for academic purposes, highlighting that their input would contribute to academic insights, not evaluations. Second, they were assured that their responses would remain completely anonymous, with no links to their personal identity. Third, respondents were told that the analysis would focus on group data rather than individual answers, reducing any pressure to respond in a socially desirable way. Fourth, participants were given the option to stop participating at any time without any negative effects, ensuring that participation was entirely voluntary. Finally, completed questionnaires were securely stored by the research team to protect participants’ information and maintain confidentiality throughout the study.

Measures

This study assessed two demographic variables: gender (male, female) and admission pathway (options included applying for admission, admission for technical excellence, admission selection, joint registration and distribution, separate admission for the continuing education division, and others). University life satisfaction was assessed with a 4-item scale from Parahoo et al. (2013). The perceived education quality scale, adapted from Annamdevula and Bellamkonda (2016) and Kahraman and Alrawadieh (2021), included 11 items. University brand knowledge was assessed with a 4-item scale based on Baumgarth and Schmidt (2010) and Balaji et al. (2016). Finally, positive word-of-mouth was assessed with a 3-item scale from Henning-Thurau et al. (2001), Schlesinger et al. (2023), and Söderlund (2006). A 5-point Likert scale was used for all items, where 1 represented “strongly disagree” and 5 represented “strongly agree”.

Prior to the main survey, a pilot test was conducted to assess the clarity and robustness of the measurement items and the accuracy of the translated content. Using a translation and back-translation procedure by independent bilingual experts, conceptual and semantic equivalence was ensured. The pilot test involved 100 participants from the target population, whose feedback led to minor wording revisions. All scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.70), confirming their reliability before formal data collection.

Data analysis planning

This study will use SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 25.0 for statistical analysis, including descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the valid questionnaire data. Regression analysis will also be conducted to investigate the research hypotheses.

Results

Descriptive analysis of participants

A total of 2638 questionnaires were given to first-year undergraduate students (including 5-year junior college students), resulting in 816 valid responses, giving a valid response rate of 30.93%. Most participants were female, making up 77.90% of the sample. The main admission pathways included admission selection (38.40%), separate admission for the continuing education division (18.30%), and joint registration and distribution admission (17.90%).

Reliability analysis

This paper uses a Cronbach’s α coefficient above 0.70 as the standard for reliability. The results show strong reliability for each factor: university life satisfaction has a Cronbach’s α of 0.96, perceived education quality is 0.98, university brand knowledge is 0.96, and positive word-of-mouth is 0.97. These results indicate that each construct in this paper has achieved a high level of reliability.

Validity analysis

This paper used CFA to investigate the validity of the scales (as shown in Table 2). Based on Hair et al. (1998), any items with factor loadings below 0.4 were considered for deletion. The results showed that all 22 observed variables were significant (t > 1.96, p < 0.05); no items needed to be deleted. High factor loadings and composite reliability (CR) suggest strong convergent validity for the scales (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Besides, convergent validity is established if the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent variable and its items exceeds 0.5 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). The AVE values for each scale were as follows: university life satisfaction at 0.85, perceived education quality at 0.85, university brand knowledge at 0.86, and positive word-of-mouth at 0.92. Since all constructs have AVE values over 0.5 and are statistically significant, the scales used in this paper show acceptable convergent validity.

Discriminant validity measures how well two different constructs are distinguished from each other. A low correlation between them indicates strong discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As noted by Hair et al. (1998), discriminant validity is achieved when the square root of each construct’s AVE is larger than its correlations with other constructs. In this study, the square roots of the AVE for each construct, ranging from 0.92 to 0.96 (see Table 3), all surpassed the correlations with other constructs. This confirms that the scales used in this paper demonstrate good discriminant validity.

Descriptive statistics of variables

Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations for all constructs. Respondents reported moderately high levels of university life satisfaction (M = 3.55, SD = 0.83), perceived education quality (M = 3.66, SD = 0.80), and university brand knowledge (M = 3.54, SD = 0.81). The mean score for positive word-of-mouth was 3.50 (SD = 0.87), indicating a generally favorable tendency to recommend the university to others.

Hypothesis tests

To test Hypotheses 1 through 3, this study used positive word-of-mouth as the dependent variable, with gender and admission pathway as control variables. University life satisfaction was the independent variable, and perceived education quality and university brand knowledge served as moderating variables. To examine whether multicollinearity posed an issue in the regression analyses for hypothesis testing, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were computed for all variables in the model. The results showed that every VIF value was below 5, far lower than the commonly accepted cut-off of 10 (Hair et al., 1998), confirming that multicollinearity was negligible and that all variables were appropriate for inclusion in the analysis. The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 4. They show that university life satisfaction has a significant positive influence on positive word-of-mouth (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), which supports Hypothesis 1.

The interaction between university life satisfaction and perceived education quality has a significant effect on positive word-of-mouth (β = 0.13, p < 0.01). As shown in Fig. 2, when perceived education quality is high, university life satisfaction has a strong positive impact on positive word-of-mouth. In a low perceived education quality context, university life satisfaction still positively impacts positive word-of-mouth, but the effect is slightly weaker than in the high-quality context. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

The interaction between university life satisfaction and university brand knowledge has a significant impact on positive word-of-mouth (β = −0.10, p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 3, when university brand knowledge is high, university life satisfaction has a positive influence on positive word-of-mouth. In a low university brand knowledge context, university life satisfaction also positively influences positive word-of-mouth, with a slightly stronger effect than in the high brand knowledge context. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Conclusion and discussion

Conclusion

Developed through a review of relevant studies and hypothesis construction, this paper proposed three research hypotheses, all of which were confirmed by the analysis results. First, the study found a positive association between university life satisfaction and students’ positive word-of-mouth about the university. This means that when students are satisfied with their university experience, they are more prone to share the university’s strengths with prospective students. Second, the study showed that perceived education quality positively moderates this relationship. In other words, when students perceive higher education quality, the connection between their satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth becomes even stronger. Finally, the study found that university brand knowledge also has a moderating effect, but in a negative direction. This suggests that when students have higher brand knowledge, they still share positive word-of-mouth, but the strength of this effect is slightly lower compared to students with lower brand knowledge. These findings reveal the nuanced role of university brand knowledge in shaping students’ word-of-mouth behavior.

Theoretical implications

Previous research has explored positive word-of-mouth in higher education from both current students and alumni, including its antecedents such as service quality, brand identification, and satisfaction (e.g., Aslan and Aslan, 2025; Dandis et al., 2022; Rasheed and Rashid, 2024; Schlesinger et al., 2023; Zeqiri et al., 2023) as well as its consequences (e.g., Amani, 2022; Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023). While these studies have provided valuable insights, most have focused on identifying direct antecedents or outcomes of word-of-mouth. Prior research has often examined satisfaction as a mediator between service quality dimensions or brand-related factors and word-of-mouth (e.g., Gabbianelli and Pencarelli, 2023; Rasheed and Rashid, 2024), but has not addressed the moderating role of perceived education quality or university brand knowledge in the satisfaction–word-of-mouth link.

Addressing this gap, the present study focuses on university life satisfaction as the primary predictor of positive word-of-mouth, while testing perceived education quality and university brand knowledge as moderators. This approach shifts the discussion from identifying isolated determinants to understanding how the effect of satisfaction on word-of-mouth changes under different institutional and perceptual conditions. Drawing on SET, the study explains that when students perceive valuable socio-emotional or developmental benefits from their university, they feel a reciprocal obligation to advocate for it, and this reciprocity can be influenced by their perceptions of education quality and brand knowledge.

In line with prior findings, the moderating effect of perceived education quality aligns with research showing that when service quality perceptions are high, satisfaction more strongly translates into advocacy behaviors (e.g., Mendoza-Villafaina and López-Mosquera, 2024). However, in contrast to our findings, previous research indicates that higher brand knowledge is associated with stronger psychological connections to the institution. For example, Balaji et al. (2016) found that university brand knowledge positively influences university identification, which in turn can shape students’ evaluative judgments and advocacy intentions. Based on this reasoning, it could be expected that stronger brand knowledge would amplify the satisfaction–word-of-mouth link; however, our results indicate a negative moderating effect. Specifically, the association between satisfaction and word-of-mouth was stronger when brand knowledge was low. One possible explanation is that students with high brand knowledge may rely more on the institution’s established reputation and distinctive features, making their word-of-mouth less dependent on personal satisfaction. Conversely, students with low brand knowledge may base their word-of-mouth primarily on their personal university experiences, causing satisfaction to have a more pronounced influence.

By integrating these moderating effects, the study contributes to the higher education management literature by showing that positive word-of-mouth is not solely a function of satisfaction but also depends on contextual and perceptual factors. This extends prior research by highlighting that the same satisfaction level may lead to different word-of-mouth intensities depending on students’ perceptions of education quality and brand knowledge. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance for universities to consider how brand communication and service quality perceptions shape the strength of advocacy behaviors among satisfied students.

Practical implications

The analysis shows that higher university life satisfaction gives rise to stronger positive word-of-mouth from students about their school. To foster this, universities should focus on enhancing the overall student experience. One approach is to establish a reliable feedback system to regularly gather students’ opinions and suggestions. By using this feedback to continuously improve services, universities can better meet students’ needs. When students are more satisfied with their university life, they are more prone to share positive word-of-mouth with prospective students, helping to attract more talented new applicants.

Additionally, this study found that when students perceive high education quality, the influence of university life satisfaction on positive word-of-mouth is even stronger. In practical terms, universities should focus on making sure staff are responsive, accessible, and treat all students fairly. Course content should be relevant and contribute to students’ knowledge, with instructors delivering high-quality teaching and following course requirements. Universities should also regularly assess students’ learning progress and provide sufficient faculty support in each department. Gathering feedback to improve services, ensuring classrooms are well-equipped, providing ample academic resources in the library, and fostering a campus environment that supports learning are all important steps to enhance students’ perception of education quality.

Finally, this study found that the strength of the relationship between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth varies by students’ level of brand knowledge. Specifically, when brand knowledge is low, satisfaction has a stronger and statistically significant effect on positive word-of-mouth; as brand knowledge increases, this effect weakens and may become insignificant at higher levels. This suggests that universities should not assume that promoting brand knowledge will always enhance the satisfaction–word-of-mouth link. For students with lower brand knowledge, efforts to improve their university life satisfaction through enriched learning experiences, supportive services, and engaging campus life are likely to yield stronger advocacy behaviors. For students with higher brand knowledge, positive word-of-mouth may depend less on their personal satisfaction and more on their perception of the institution’s reputation or distinctive strengths, indicating that strategies beyond brand promotion, such as reinforcing personal engagement and aligning experiences with expectations, may be more effective.

Limitations and future research directions

This study’s response rate was 30.93%, likely due to voluntary participation without incentives, overlap with midterm examinations, and survey fatigue from concurrent institutional questionnaires. This represents an important limitation of the research. Future studies could employ mixed-mode data collection strategies (e.g., combining online and in-person surveys) or offer incentives to improve response rates and reduce potential bias. Moreover, the participants in this paper were first-year undergraduate students (including 5-year junior college students) from a university in central Taiwan. Whether these findings can be applied to other higher education organizations in Taiwan remains to be seen. Future research could investigate this by conducting larger-scale surveys across different universities or in cross-institutional contexts to test the generalizability of these results. Additionally, Schlesinger et al. (2023) found that university brand image is a significant factor in driving positive word-of-mouth, while this study suggests that brand image might serve as a key contextual factor. Future research could examine the moderating effect of university brand image in the relationship between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth. Finally, student trust—reflecting their perception of the university’s reputation and the value of its academic programs (Sultan and Wong, 2012)—could also play a role. Future studies might investigate whether student trust moderates the link between university life satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth.

Data availability

Data generated and analyzed during this study can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Akareem HS, Hossain SS (2016) Determinants of education quality: What makes students’ perception different? Open Rev Educ Res 3(1):52–67

Aldhobaib MA (2024) Quality assurance struggle in higher education institutions: moving towards an effective quality assurance management system. High Educ 88:1547–1566

Alimen N, Guldem C (2010) Dimensions of brand knowledge: Turkish university students’ consumption of international fashion brands. J Enterp Inf Manag 23(4):538–588

Amani D (2022) I have to choose this university: understanding perceived usefulness of Word of Mouth (WOM) in choosing universities among students of higher education. Serv Mark Q 43(1):1–16

Annamdevula S, Bellamkonda RS (2016) Effect of student perceived service quality on student satisfaction, loyalty and motivation in Indian universities: development of HiEduQual. J Model Manag 11(2):488–517

Aslan M, Aslan H (2025) The interplay of brand identification, satisfaction, and psychological well-being: a mediational role of positive word-of-mouth behavior in higher education. BMC Psychol 13(1):1–14

Bagozzi RP, Yi YJ (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation model. J Acad Mark Sci 16(1):74–94

Baker TL, Rapp A, Meyer T, Mullins R (2014) The role of brand communications on front line service employee beliefs, behaviors, and performance. J Acad Mark Sci 42(6):642–657

Balaji MS, Roy SK, Sadeque S (2016) Antecedents and consequences of university brand identification. J Bus Res 69(8):3023–3032

Baruönü FÖ (2025) Examining the motives affecting the demand for second-hand fashion products in the context of brand knowledge presence. J Prod Brand Manag 34(5):707–719

Baumgarth C, Schmidt M (2010) How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of `internal brand equity' in a business-to-business setting. Ind Mark Manag 39:1250–1260

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY

Calvo-Porral C, Lévy-Mangin JP, Novo-Corti I (2013) Perceived quality in higher education: an empirical study. Mark Intell Plan 31(6):601–619

Cao JT, Foster J, Yaoyuneyong G, Krey N (2019) Hedonic and utilitarian value: the role of shared responsibility in higher education services. J Mark High Educ 29(1):134–152

Chankseliani M, Qoraboyev I, Gimranova D (2021) Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: new empirical and conceptual insights. High Educ 81:109–127

Chen CT (2016) The Investigation on Brand image of university education and students’ word-of-mouth behavior. High Educ Stud 6(4):23–33

Cropanzano R, Anthony EL, Daniels SR, Hall AV (2017) Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad Manag Ann 11(1):479–516

Dandis AO, Jarrad AA, Joudeh JMM, Mukattash IL, Hassouneh AG (2022) The effect of multidimensional service quality on word of mouth in university on-campus healthcare centers. TQM J 34(4):701–727

De-Juan-Vigaray MD, Ledesma-Chaves P, González-Gascón E, Gil-Cordero E (2024) Student satisfaction: examining capacity development and environmental factors in higher education institutions. Heliyon 10(17):e36699

Diener E, Diener M (1995) Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J Personal Soc Psychol 68(4):653–663

Drewes T, Michael C (2006) How do students choose a university? An analysis of applications to universities in Ontario, Canada. Res High Educ 47(7):781–800

Elsharnouby MH, Mohsen J, Saeed OT, Mahrous AA (2021) Enhancing resilience to negative information in consumer–brand interaction: the mediating role of brand knowledge and involvement. J Res Interact Mark 15(4):571–591

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Frenzen J, Nakamoto K (1993) Structure, cooperation, and the flow of market information. J Consum Res 20(3):360–375

Gabbianelli L, Pencarelli T (2023) On-campus accommodation service quality: the mediating role of students’ satisfaction on word of mouth. TQM J 35(5):1224–1255

Gallarza M, Fayos T, Arteaga F, Servera D, Floristán E (2020) Different levels of loyalty towards the higher education service: evidence from a small university in Spain. Int J Manag Educ 14(1):36–48

Greenacre L, Freeman L, Cong K, Chapman T (2014) Understanding and predicting student word of mouth. Int J Educ Res 64:40–48

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Heffernan T, Wilkins S, Mohsin M (2018) Transnational higher education: the importance of institutional reputation, trust and student-university identification in international partnerships. Int J Educ Manag 32(2):227–240

Henning-Thurau T, Langer M, Hansen U (2001) Modelling and managing student loyalty: an approach based on the concept of relationship quality. J Serv Res 3(1):331–344

Homans GC (1958) Social behavior as exchange. Am J Sociol 63(6):597–606

Ismail IJ (2025) A perceived usefulness of entrepreneurship education as a marketing model for students’ choice of universities: Does the electronic word of mouth matter? Int J Educ Manag 39(3):617–636

Kahraman OC, Alrawadieh DD (2021) The impact of perceived education quality on tourism and hospitality students’ career choice: the mediating effects of academic self-efficacy. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ 29:100333

Keller K (2003) Brand synthesis: the multidimensionality of brand knowledge. J Consum Res 29(4):595–600

Kirmani MN, Sharma P, Anas M, Sanam R (2015) Hope, resilience and subjective wellbeing among college going adolescent girls. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Stud 2(1):262–270

Kuvaas B, Shore LM, Buch R, Dysvik A (2020) Social and economic exchange relationships and performance contingency: differential effects of variable pay and base pay. Int J Hum Resour Manag 31(3):408–431

Le TD, Dobele AR, Robinson LJ (2018) Information sought by prospective students from social media electronic word-of-mouth during the university choice process. J High Educ Policy Manag 41(1):18–34

Le TD, Robinson LJ, Dobele AR (2020) Understanding high school students use of choice factors and word-of-mouth information sources in university selection. Stud High Educ 45(4):808–818

Lee D, Ng PML, Bogomolova S (2020) The impact of university brand identification and eWOM behaviour on students’ psychological well-being: a multi-group analysis among active and passive social media users. J Mark Manag 36(3-4):384–403

Li IW, Jackson D, Koshy P (2025) Students’ reported satisfaction at university: the role of personal characteristics and secondary school background. High Educ 89:1513–1531

Liu X, Wang J (2024) Depression, anxiety, and student satisfaction with university life among college students: a cross-lagged study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:1172

Mendoza-Villafaina J, López-Mosquera N (2024) Educational experience, university satisfaction and institutional reputation: implications for university sustainability. Int J Manag Educ 22(3):101013

Oldfield BM, Baron S (2000) Student perceptions of service quality in a UK university business and management faculty. Qual Assur Educ 8(2):85–95

Parahoo SK, Harvey HL, Tamim RM (2013) Factors influencing student satisfaction in universities in the Gulf region: Does gender of students matter? J Mark High Educ 23(2):135–154

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Rabah HA, Dandis AO, Eid MAH, Tiu Wright L, Mansour A, Mukattash IL (2024) Factors influencing electronic word of mouth behavior in higher education institutions. J Mark Commun 30(8):988–1012

Rasheed R, Rashid A (2024) Role of service quality factors in word of mouth through student satisfaction. Kybernetes 53(9):2854–2870

Raza SA, Qazi W, Umer B, Khan KA (2020) Influence of social networking sites on life satisfaction among university students: a mediating role of social benefit and social overload. Health Educ 120(2):141–164

Reeve J, Lee W (2019) A neuroscientific perspective on basic psychological needs. J Personal 87(1):102–114

Rehman MA, Woyo E, Akahome JE, Sohail MD (2022) The influence of course experience, satisfaction, and loyalty on students’ word-of-mouth and re-enrolment intentions. J Mark High Educ 32(2):259–277

Schlesinger W, Cervera-Taulet A, Wymer W (2023) The influence of university brand image, satisfaction, and university identification on alumni WOM intentions. J Mark High Educ 33(1):1–19

Scott T, Guan W (2023) Challenges facing Thai higher education institutions financial stability and perceived institutional education quality. Power Educ 15(3):326–340

Singh S, Jasial SS (2021) Moderating effect of perceived trust on service quality–student satisfaction relationship: evidence from Indian higher management education institutions. J Mark High Educ 31(2):280–304

Sipilä J, Herold K, Tarkiainen A, Sundqvist S (2017) The influence of word-of-mouth on attitudinal ambivalence during the higher education decision-making process. J Bus Res 80:176–187

Skinner BT (2019) Choosing college in the 2000s: an updated analysis using the conditional logistic choice model. Res High Educ 60(2):153–183

Söderlund M (2006) Measuring customer loyalty with multi-item scales: a case for caution. Int J Serv Ind Manag 171(1):76–98

Stribbell H, Duangekanong S (2022) Satisfaction as a key antecedent for word of mouth and an essential mediator for service quality and brand trust in international education. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9:438

Sultan P, Wong HY (2012) Service quality in a higher education context: an integrated model. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 24(5):755–784

Vukasovič T (2015) Managing consumer-based brand equity in higher education. Manag Glob Transit 13(1):75–90

Weisser RA (2020) How personality shapes study location choices. Res High Educ 61:88–116

Wilkins S, Butt MM, Kratochvil D, Balakrishnan MS (2016) The effects of social identification and organizational identification on student commitment, achievement and satisfaction in higher education. Stud High Educ 41(12):2232–2252

Wong WH, Chapman E (2023) Student satisfaction and interaction in higher education. High Educ 85:957–978

Žalėnienė I, Pereira P (2021) Higher education for sustainability: a global perspective. Geogr Sustain 2(2):99–106

Zeqiri J, Dania TR, Lupșa-Tătaru DA, Gagica K, Gleason K (2023) The impact of e-service quality on word of mouth: a higher education context. Int J Manag Educ 21(3):100850

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chin-Lon Lin contributed significantly across various aspects of the research, including writing (original draft and review/editing), visualization, validation, supervision, resource coordination, project administration, methodology design, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization. Wen-Long Zhuang played a key role in writing (both the original draft and review/editing), visualization, validation, supervision, resource coordination, project management, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization. Hsiu-Chen Huang focused on writing (original draft and review/editing), visualization, validation, supervision, resource coordination, methodology development, and conceptualization of the research framework. Ming-Tsung Lee contributed to writing (original draft and review/editing), software development, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization. Sung-Hui Wu contributed to writing (original draft and review/editing), software development, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study used anonymized data provided by the Office of Institutional Research of the authors’ institution. The dataset did not contain personally identifiable information, and the study involved no intervention or interaction with participants. According to the Education Discipline Review Guidelines of the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (revised 2022), research that is anonymous, non-interventional, non-interactive, and contains no personally identifiable information is exempt from formal ethical review (see Section II.2, Research Ethics Review Exemptions). (National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan. Education Discipline Review Guidelines (revised 2022). Available at: https://www.nstc.gov.tw/hum/ch/detail/da71f59b-9ab8-41f4-ae93-5973e0701cc7). The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Not applicable. As this study relied on anonymized institutional data and involved no direct contact with participants, individual informed consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CL., Zhuang, WL., Huang, HC. et al. Do satisfied students generate positive word-of-mouth? Moderating roles of perceived education quality and university brand knowledge. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05840-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05840-6