Abstract

The cornerstone of teachers’ professional development in the digital age is the transformation of their role from mere users of digital technology to co-creators of digital knowledge. Exploring the relationship between teachers’ knowledge-sharing behaviors and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) holds substantial practical implications. This study surveyed 1300 primary and secondary school teachers to investigate how gender and social-technical capital mediate the relationship. The results reveal a significant positive correlation between teachers’ knowledge sharing and TPACK in the digital age, with social-technical capital serving as a mediator and its effect moderated by gender. Furthermore, this study provides empirical support for key propositions of knowledge management theory and social capital theory, focusing on teachers’ knowledge structures and professional development in the digital age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 21st century, knowledge has become the most significant resource and primary driver of value creation, particularly within the digital society that has fundamentally reshaped knowledge production, dissemination, and acquisition (Bélisle, 2006). Central to this transformation is teachers’ digital literacy exemplified by Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)—a framework integrating technology, pedagogy, and subject matter expertise to navigate evolving educational demands. A key mechanism enhancing digital literacy is teacher knowledge sharing, defined as the collaborative exchange of knowledge resources among educators within a group, facilitating both knowledge transmission and creation. Digital technology has introduced new platforms for knowledge sharing, strengthening connections between knowledge networks with educators and establishing knowledge sharing behavior as an essential element of teachers’ professional development in the digital age (Huang et al., 2023). While existing research emphasizes the interaction between teachers’ knowledge sharing and TPACK, few studies explore how “social-technical capital”—social relationships enabled by digital networks—moderates this relationship. Additionally, the influence of teacher gender on knowledge-sharing dynamics in digital environments remains unclear. To address these gaps, the present study draws on knowledge management theory and social capital theory, to answer two core questions: (1) How does teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior influence their TPACK development in the digital age? (2) How do gender differences and social-technical capital moderate this relationship? This study aims to provide a theoretical foundation for improving teachers’ digital literacy.

Teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK

Knowledge sharing, as a knowledge-centered activity, refers to the exchange of experiences, facts, skills, and expertise within an organizational context (Malik, Kanwal (2018)). It functions as a professional practice where individuals collaborate to share information for completing specific tasks, thereby enhancing task performance (Deng et al., 2023). Moreover, it serves as a critical mechanism through which organizational members apply knowledge, foster innovation, and establish competitive advantages for the organization (Jacksons et al., 2006; Wang & Noe, 2010; Deng et al., 2023; Olan et al., 2022). Based on the representability of knowledge resources, knowledge sharing is classified into two categories: explicit knowledge sharing and tacit knowledge sharing (Cummings, 2004; Pulakos (2003); Eslami et al., 2023; Perotti et al., 2024). The distinction between these two types of knowledge profoundly shapes teachers’ approaches to knowledge management and professional development. Explicit knowledge, due to its high codifiability, is often disseminated rapidly through digital platforms via written documents and oral presentations, enabling teachers to efficiently access structured information and reduce redundant workloads. In contrast, the complexity and ambiguity of tacit knowledge pose significant challenges for encoding and dissemination. This type of sharing relies on highly interactive scenarios to transfer experiential insights, which are critical for fostering adaptive teaching practices and innovation. To measure knowledge sharing behavior, Yi (2009) developed the Knowledge Sharing Behavior Scale (KSBS), which includes four dimensions: written contribution, organizational communication, personal interaction, and community of practice. This 28-item scale has been widely adopted across countries and validated for assessing the types and extent of knowledge sharing (Ozbebek et al., 2011; Ramayah et al., 2013; Palacios-Marquéz et al., (2013); Ramayah et al., 2014). Digital technology-based social media provide new avenues for knowledge sharing and significantly influence the behaviors of both individuals and organizations (Ahmed et al., 2019; Lepore et al., 2021). Digital platforms increasingly enable teachers to share knowledge, facilitating the production, creation, and dissemination of information through teaching activities (Kim & Ju, 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2009). In the digital age, teacher knowledge sharing behavior involves leveraging digital technologies to disseminate knowledge, skills, experiences, and insights. This process encompasses obtaining, exchanging, internalizing, and reconstructing knowledge, thereby promoting professional development. It represents a resource exchange process that includes both knowledge contribution and acquisition.

Referencing to Shulman’s framework of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) (Shulman, 1986) and research on teachers’ technology integration (Pierson, 2001; Mouza, 2003), TPCK was formally proposed in 2005 (Koehler & Mishra, 2005). Due to pronunciation challenges, the acronym was renamed to TPACK. TPACK comprises three core elements including Technological Knowledge (TK), Pedagogical Knowledge (PK), and Content Knowledge (CK). These core elements interact to generate four composite elements, forming a complex, loosely coupled knowledge structure in which the elements are interconnected yet distinct. They dynamically interact with composite elements and specific contexts, creating a balanced and adaptive system. The framework not only emphasizes the essential role of technological knowledge in reshaping pedagogical and content knowledge but also underscores the critical function of knowledge sharing in TPACK development. Specifically, teachers’ knowledge sharing behaviors facilitate the dynamic interplay among technology, pedagogy, and subject matter expertise, thereby serving as a core mechanism for professional growth in the digital age. Consequently, TPACK serves as a valuable enhancement to teachers’ knowledge structures in the digital age. Various TPACK measurement instruments have been developed, with one of the most prominent being the Survey of Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Teaching and Technology (SPTK-TT) by Schmidt et al. (2009), which aligns with the TPACK framework and comprises seven knowledge components and 47 items. Building on this foundation, Chai et al. (2012) subsequently developed the TPACK for Meaningful Learning Survey.

The essence of teachers’ knowledge sharing is a two-way interactive and dialogic process among teacher collaborators, emphasizing the active participation of knowledge sharing participants and the contextual nature of the knowledge sharing platform. Notably, the advancement of digital technology has created a shared, digital, and interactive educational environment for classroom teaching. Within this environment, teachers need to leverage their initiative and focus on the integrated knowledge system comprising interrelated technological knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and content knowledge. The research indicates that peer sharing of technical skills within teacher network research communities facilitates teachers’ continuous learning and assists in establishing connections between technological knowledge (TK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and content knowledge (CK), thereby enhancing teachers’ TPACK levels (Koh & Divaharan, 2011). Building on this perspective, knowledge management theory positions knowledge sharing as a core component of knowledge management (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Yeh et al., 2012), one that involves the storage and dissemination of teachers’ knowledge through digital technology and, more critically, promotes their professional development through individual knowledge management. Furthermore, teachers’ knowledge systems are organized, systematic structures encompassing various types of knowledge. With the integration of digital technology into the knowledge sharing process, teachers must accept and internalize shared knowledge while transforming it into their own and reconstructing their personal knowledge frameworks. Crucially, the symbiotic integration of digital technology and knowledge sharing has enriched the complexity and depth of teachers’ knowledge structures. Ultimately, the TPACK framework, as a system that effectively integrates digital technology into classroom instruction, has become a critical standard for advancing teachers’ professional development. Based on this theoretical and empirical foundation, the study hypothesizes that the active exchange of knowledge in the digital age directly fuels TPACK development. Therefore, the research hypothesis is as follows:

H1: Teachers’ knowledge sharing behaviors shows a positive correlation with their TPACK in the digital age.

Teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior, social-technical capital and TPACK

The advent of digital technology has introduced new forms of social capital, particularly online social capital. Online social capital pertains to resources embedded in virtual social networks, contrasting with offline social capital, which resides in physical networks (Williams, 2006). In the present study, social-technical capital is defined specifically as online social capital. The term “social-technical capital” emphasizes the interaction between digital technology and social relationships in shaping teachers’ knowledge-sharing dynamics. Moving beyond a narrow focus on resource accumulation, it underscores how technology actively mediates, structures, and amplifies social interactions. Similar to offline social capital, it arises from interpersonal networks but operates uniquely within the context of Internet-based interactions. It is a type of social resource mobilized and exchanged by individuals. Digital technology facilitates teachers’ digital socialization on Internet platforms, promoting communication, trust, and the exchange of teaching experiences and practices (Wang & Noe, 2010). Moreover, digital technology has become an essential tool for advancing knowledge sharing, accelerating the dissemination and transfer of explicit and tacit knowledge within organizations, and improving how individuals share knowledge (Lin et al., 2020). Crucially, social-technical capital emphasizes the role of technology in fostering and sustaining social relationships by highlighting the interaction between social networks and technological support (Resnick, 2002). It seeks to promote collaborative cooperation, building mutually beneficial relationships, shared norms, and trust. Consequently, teachers’ knowledge sharing behaviors in the digital age enhance their social-technical capital by leveraging digital interactions and relationships.

The framework builds upon social capital theory, which emphasizes the significance of social relationships, trust, and shared norms in enabling resource exchange, including knowledge (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Bhandari & Yasunobu, 2009). By extension, social-technical capital integrates these social elements with technological mediation to amplify knowledge-sharing efficacy. Empirical evidence confirms that both offline and online social capital significantly enhance knowledge exchange, with digitally connected teachers demonstrating greater propensity to share pedagogical insights (Akhavan, Mahdi (2016); Chiu et al., 2006). In online teacher communities, teachers with stronger social ties and greater levels of trust are more inclined to share teaching knowledge and practices. Social-technical systems foster frequent knowledge exchanges and promote the dissemination of shared resources (Zhang & Venkatesh, 2013). Social-technical capital influences knowledge sharing behavior and strengthens professional capabilities through its supportive infrastructure. Digital tools and platforms that constitute social-technical capital ensure the efficient dissemination and practical application of shared knowledge in educational contexts (Treem & Leonardi, 2012). Consequently, teachers participating in digital media communities can effectively exchange resources and ideas, which contributes to enhancing their TPACK (Ranieri et al., 2012). The interconnections among knowledge sharing, social-technical capital, and TPACK are rooted in their shared dependence on digitally mediated social ecosystems. Knowledge sharing acts as the behavioral catalyst that activates social-technical capital accumulation: when teachers exchange pedagogical insights through digital platforms, they simultaneously strengthen network ties, reinforce mutual trust, and co-construct professional norms. The technology and interpersonal relationships facilitated by social-technical capital serve as a foundation for translating teachers’ knowledge-sharing behaviors into TPACK capabilities within the digital age. This study suggests a strong positive correlation between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and social-technical capital, which in turn enhances TPACK. Therefore, the research hypothesis is as follows:

H2: Social-technical capital mediates the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK.

The role of teachers’ gender

Gender, as a socially constructed determinant of power and status, manifests in measurable disparities across physiological, psychological, social-cognitive, and behavioral dimensions (Goktan & Gupta, 2015). Within the framework of social capital theory, gender is a crucial factor in shaping how digital technology is used for knowledge sharing (Chai et al., 2011; Grubić-Nešić et al., 2015). Studies indicate that women are typically less inclined to share information in public domains than men (Thakadu, 2018; Durand et al., 2022). Gender differences are also observed in teachers’ TPACK (Bingimlas, 2018; Ma & Baek, 2020). Research shows that female science teachers are more confident in pedagogical knowledge but less confident in technological knowledge than their male counterparts (Lin et al., 2013). Male teachers also tend to perceive themselves as having a TPACK advantage over female teachers (Scherer et al., 2017). However, other studies indicate no significant gender differences in TPACK (Jang & Tsai, 2012; Cetin-Dindar et al., 2018; Deng et al., 2023; Fabian et al., 2024). Disparities in social capital across different times and spatial contexts have been described as the “gender gap” (He Zun et al., 2023). Women’s social capital is generally more homogeneous and less diverse, resulting in a lower stock compared to men’s. The “gender digital divide,” as discussed in Chinese academic literature, underscores disparities between men and women in accessing and using digital technology resources (Zhang, 2024). Based on this, the present study posits that gender differences may lead to variations in social-technical capital, affecting the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK in the digital age. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Gender plays a moderating role in the mediating effect of social-technical capital between knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This study employed a cluster random sampling approach across China’s four major economic regions—eastern, central, western, and northeastern—and conducted an online survey of primary and secondary school teachers. Specifically, invitations containing the survey link were distributed via popular teacher-focused social platforms (e.g., WeChat teacher groups and DingTalk communities). The questionnaire was reviewed by the Academic ethics committee of A University, which agreed to carry out the investigation. Before inviting each participant to fill out the questionnaire, informed the purpose of the study and the scope of data use. Participants can quit at any time if discomfort occurs during the filling process. In total, 1,525 questionnaires were collected. After excluding invalid questionnaires—those with consistent responses or completed too quickly—1,300 valid responses were retained, resulting in an effective response rate of 85.2%. Among the respondents, 238 were male (18.3%) and 1,062 were female (81.7%). The basic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Measures

The scale of teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior in the digital age

The scale used to measure teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior in the digital age, adapted from Ramayah et al.‘s (2014) Knowledge Sharing Behavior Scale (KSBS), assesses four dimensions: digital written contribution, digital organizational communication, personal digital interaction, and online communities of practice. It comprises 16 items. Digital written contributions refer to teachers sharing teaching and research outcomes through digital documents such as Tencent Docs, WPS Docs, blog, wiki and Facebook for collaborative discussions. Digital organizational communication encompasses formal interactions and knowledge sharing through online video conferencing tools like Tencent Meeting and DingTalk to address educational issues. Personal digital interaction pertains to informal knowledge exchanges among teachers via social platforms like WeChat and QQ. Online communities of practice involve teachers informally sharing knowledge within teacher communities on large scale digital platforms such as the China Education Research Network and the National Smart Education Platform. For example, one item measuring “digital written contributions” states, “I frequently use online collaboration tools (e.g., Tencent Docs, WPS Docs, blogs, wikis, and Facebook) to co-create teaching materials and engage in research discussions with colleagues”. Another item accessing “digital organizational communication” states, “I regularly initiate discussions on school-related educational practices through video conferencing platforms (e.g., Tencent Meeting, DingTalk), proposing actionable solutions to pedagogical challenges”. Responses were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The scale demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.902, exceeding the conventional threshold of α ≥ 0.80 for strong internal consistency.

TPACK scale

The TPACK scale used in this study was adapted from Chai et al.‘s (2012) TPACK-ML survey scale. The most representative item, based on the highest confirmatory factor loading, was selected from each of the seven dimensions. Items were revised to include references to digital technologies, such as multimedia, big data, the Internet, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality, resulting in a total of seven items. For example, one item measuring TK states, “I am able to integrate the use of Web 2.0 tools (e.g., blog, wiki, Facebook) for students’ learning”. Another item accessing PK states, “I teach my students to adopt appropriate learning strategies”. Responses were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The scale demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.905, exceeding the conventional threshold of α ≥ 0.80 for strong internal consistency.

Social-technical capital scale

This study developed a Teacher’s Social-technical Capital Scale grounded in the technological capital theory model by Carlson and Isaacs (2018). To ensure validity, the scale underwent a multi-stage validation process: Initial items were derived from literature on digital literacy and social capital, followed by expert reviews (N = 12) to assess content relevance. A preliminary version was administered to 644 in-service teachers. After screening and cleaning the data, the data shows: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) confirmed the hypothesized four-factor structure (KMO = 0.972, p < 0.001), and factor loadings (>0.850) guided final item selection. Ambiguous items were revised for clarity based on pilot feedback. The final scale comprises 15 items across four dimensions: digital awareness, digital knowledge, digital access, and digital capacity of the individual’s social collective. Digital awareness assesses teachers’ recognition of specific digital technologies and their awareness of potential applications (e.g., multimedia, big data, artificial intelligence, etc.). Digital knowledge measures teachers’ procedural understanding of effectively operating digital technologies for educational purposes (e.g., understanding methods for solving problems with technology). Digital access evaluates teachers’ ability to access digital technologies and potential barriers to their use (e.g., access to widely used educational technologies). Digital capacity of the individual’s social collective refers to teachers’ professional networks—such as school-based departments, cross-district collaborations, and online communities—to harness digital technologies for collective benefits. This dimension examines how members within a teacher’s network enhance knowledge sharing through technology-mediated interactions (e.g., identity verification on digital platforms for knowledge sharing). For example, one item measuring “digital awareness” states, “I am familiar with widely used digital technologies (e.g., multimedia, big data, Internet, artificial intelligence, virtual reality)”. Another item accessing “digital knowledge” states, “I can effectively apply principles and methods for selecting appropriate digital devices, software, and platforms in educational context”. Responses were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The scale demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.925, exceeding the conventional threshold of α ≥ 0.80 for strong internal consistency.

Data analysis

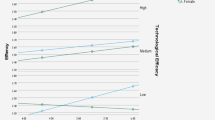

In the present study, the SPSS Macro Program Process is utilized for data analysis. In line with Hayes’ approach (2018), Model 4, a simple mediation model, is implemented to determine the mediating role of social-technical capital between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK. Model 14 extends Model 4 by introducing gender as a moderator of the mediation path. To probe the gender and social-technical capital interaction, simple slope analyses were conducted at ±1 SD of social-technical capital. Interaction plots were generated by plotting TPACK scores at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of social-technical capital, stratified by gender.

Results

Common method bias

To test for common method variance, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) on all questionnaire items. The unrotated factor analysis revealed seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first factor explained 34.14% of the variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This indicates that there is no significant common method bias in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Q-Q graph shows that the data basically presents a normal distribution. The correlation analysis between the variables is illustrated in Table 2. Firstly, teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior exhibits a significantly positive relationship with TPACK (r = 0.423, p < 0.01). Secondly, teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior demonstrates a significantly positive association with social-technical capital (r = 0.609, p < 0.01). Finally, social-technical capital is significantly related to TPACK (r = 0.497, p < 0.01).

Mediating effect analysis

After controlling for background variables, such as gender, age, and teaching time, teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior (KSB) demonstrated a significant direct effect on TPACK (β = 0.403, p < 0.001; ΔR² = 0.196, F (1, 1300) = 35.003, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H1. This direct relationship suggests that sharing pedagogical and technological resources among teachers independently enhances their ability to integrate technology into subject-specific teaching practices, potentially through immediate peer learning and resource accessibility. Concurrently, KSB exhibited a strong positive association with social-technical capital (STC) (β = 0.531, p < 0.001; ΔR² = 0.426, F (1, 1300) = 106.381, p < 0.001), which in turn significantly predicted TPACK (β = 0.406, p < 0.001; ΔR² = 0.282, F (1, 1300) = 50.519, p < 0.001). Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

In addition, the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap shows that the potential mediating effect of social-technical capital on the correlation between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK is statistically significant (Indirect effect =0.216, Boot SE = 0.021, 95% CI = [0.174, 0.255]). Therefore, hypothesis 2 is proven in the light of derived results. This indirect pathway underscores the critical role of digitally mediated social networks: teachers who leverage online communities and collaborative platforms not only share knowledge but also cultivate trust and resource reciprocity, which amplify TPACK development over time. The detailed results are shown in Table 4.

Moderated mediating effect analysis

The moderated mediating effect was conducted using the Bootstrapping method (sample size of 5000, 95% confidence interval; Model 14; Hayes, 2018), with teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior as the independent variable, social-technical capital as the mediator, gender as the moderator, and TPACK as the dependent variable. Controlling for background variables, such as age and teaching time, the detailed results are shown in Table 5.

The simple slope analysis results, presented in Fig. 1, further examine the moderating effect of gender. For male teachers, social-technical capital significantly predicted TPACK (bsimple = 0.535, t = 8.260, p < 0.001). For female teachers, while the positive predictive effect also remained significant, the coefficient was lower (bsimple = 0.386, t = 11.227, p < 0.001). PROCESS also analyzed the mediating effect of social-technical capital between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK across genders, showing a mediating effect of 0.205 for female teachers (Boot SE = 0.021, 95% CI = [0.163, 0.244]) and 0.284 for male teachers (Boot SE = 0.036, 95% CI = [0.215, 0.253]). These results highlight that the mediating role of social-technical capital is more pronounced in the male group. Additional analysis shows that the moderating index of gender on social-technical capital is −0.079 (Boot SE = 0.035, 95% CI = [−0.149, −0.012]). This finding confirms a significant gender difference in the mediating effect of social-technical capital.

Discussion

Positive correlation between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK

In the digital age, teachers’ knowledge sharing behaviors show a positive correlation with TPACK. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that knowledge sharing is crucial for enhancing professional capabilities, including TPACK (Voogt et al., 2016). Empirical studies consistently emphasize that collaborative knowledge production enables educators to overcome individual limitations in complex digital integration scenarios. For instance, Boschman et al. (2015) found that collaborative knowledge sharing during the design of technology-rich activities facilitates the integration of technological tools with teaching strategies, fostering TPACK development. Participation in online teaching communities also enhances teachers’ capacity to integrate technology into instruction effectively (Tondeur et al., 2017). Knowledge sharing bridges gaps by fostering peer collaboration, enabling a deeper understanding and transferring knowledge that cannot be acquired in isolation (Vanden, De (2004)). This study extends prior work by demonstrating that digital-era knowledge sharing transcends mere gap-filling—it generates novel knowledge forms that surpass individual cognitive boundaries. Digital technologies reconfigure knowledge flows, dismantling cognitive silos and enabling cross-community co-evolution of technology-integrated expertise. Teachers’ knowledge-sharing practices thus function as a dynamic value-creation system, supplementing hard-to-attain individual knowledge and elevating TPACK through collective intelligence. Additionally, this study contributes to knowledge management theory. Effective knowledge sharing and management are vital for value creation, performance improvement, and fostering innovation (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995, Wang & Wang, 2012). In the digital age, teachers’ knowledge sharing increases the value of their knowledge, enhances their knowledge structures, and supports the absorption and internalization of new knowledge through effective management. In digital educational contexts, teachers dualize as both “consumers” of technology-integrated knowledge—absorbing cognitive schemas from peer practices—and “producers” who codify personal pedagogical insights into shareable solutions. This dual role propels iterative cycles of knowledge decoding and encoding, enabling qualitative leaps in technology integration capabilities. Therefore, knowledge sharing is integral to improving teachers’ TPACK levels. Promoting knowledge sharing significantly updates teachers’ knowledge, enhances teaching quality, and fosters the development of high-quality educators.

The mediating role of teachers’ social-technical capital

Social-technical capital plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and their TPACK in the digital age. Previous studies have confirmed the similar role of social capital in promoting knowledge sharing (Swanson et al., 2020). Social capital enhances knowledge sharing by improving communication and sharing motivations (Hau et al., 2013). Individuals with high social capital are more confident and innovative when sharing knowledge (Mura et al., 2016). Further research has examined the impact of different dimensions of social capital on knowledge sharing. It was found that the structural dimension significantly influences the willingness to share knowledge, whereas the relational and cognitive dimensions have less significant effects (Zhao et al., 2012). Digital social platforms have restructured the architectural features of teachers’ social capital, as online collaboration tools weave once-isolated educator nodes into dynamic knowledge networks. This shift has redirected the influence of structural dimensions from physical to virtual spaces, enabling teachers to access diverse technology-integrated solutions across disciplines and institutions. Consequently, teachers’ knowledge-sharing behaviors are increasingly shaped by their positions within these digital networks rather than the strength of traditional interpersonal relationships. This evolution explains why social-technical capital continues to play a pivotal role in the digital age.

Although there is currently a lack of direct research on social-technical capital, existing evidence indicates that social capital improves communication and coordination through digital technology, thereby promoting knowledge sharing and enhancing work performance (Deng et al., 2023). In the context of Chinese culture, both social capital and technological support have significant impacts on knowledge sharing (Xu, Liu (2023); Li, Wang (2021)). In the digital age, teachers’ social-technical capital is manifested in their social relationships and interactions, which rely on teachers’ professional learning and development activities through social media platforms and online interactions (Prestridge, 2019). According to knowledge management theory, technical systems that promote knowledge flow (such as knowledge sharing platforms and databases) are important driving factors for knowledge management (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Digital knowledge sharing platforms not only serve as repositories for knowledge storage but also act as conduits for facilitating knowledge flow. During the accumulation of social-technical capital, teachers achieve iterative enhancements in technological integration capabilities through continuous knowledge contribution and acquisition. This process reveals the mediating role of social-technical capital across three dimensions: digital technologies lowering participation barriers to knowledge sharing, teachers’ social networks broadening the reach of knowledge dissemination, and the accumulation of social-technical capital strengthening the sustainability of knowledge transformation. The presence of this multilayered mediation mechanism enables the maximization of knowledge sharing efficacy in advancing teachers’ professional development. Therefore, this study further enriches the knowledge management theory from the perspective of teachers’ TPACK. With the support of digital technology, the convenient and efficient way of knowledge dissemination enables teachers to accumulate social-technical capital on digital platforms at a much faster rate than in offline situations, thereby quickly establishing trust and emotional bonds, promoting continuous knowledge sharing, and further enhancing teachers’ TPACK levels.

The moderating effect of gender

The moderating effect of gender on the second half of the path from teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior to TPACK, mediated by social-technical capital, is significant. Specifically, in male teacher groups, the indirect effect through social-technical capital on TPACK is pronounced, whereas in female teacher groups, this effect is weaker. This indicates that social-technical capital plays a stronger mediating role among male teachers. These findings, corroborated by existing studies, confirm the moderating effect of gender. Previous research has confirmed that gender serves as a key moderating factor in knowledge sharing behavior. Specifically, gender influences knowledge sharing by affecting the expectation of social capital, thereby promoting the continuous willingness to share knowledge (Lu, Lee (2012)). Additionally, gender moderates the relationship between motivation and knowledge sharing (Choi et al., 2020). From the perspective of social capital, male teachers exhibit higher levels of interpersonal trust compared to female teachers, which facilitates the development of strong relationship capital and, consequently, greater social capital (Li et al., 2023). Digital technology has reshaped teachers’ social interactions, with male teachers generally showing greater interest and acceptance of digital tools and typically possessing more technological capital than their female counterparts (Yan et al., 2019). As a result, male teachers who possess more social-technical capital are better positioned to access information and resources in digital knowledge sharing activities, thereby enhancing their TPACK levels. However, some studies indicate that as digital technology becomes more widespread, the differences in digital capital between male and female teachers are not statistically significant, suggesting that gender-related inequalities in this area are gradually diminishing (Blank & Groselj, 2014; Ragnedda et al., 2019). This study confirms the moderating role of gender in the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior, social-technical capital, and TPACK. However, due to the relatively low proportion of male teachers in the sample of this study, this may affect the universality of the research conclusions.

Conclusion

In the digital age, teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior is a significant predictor of their TPACK levels. Social-technical capital partially mediates the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK, with gender moderating this effect. This mediating effect is particularly pronounced among male teachers. This study examines and validates the relationships among teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior, social-technical capital, gender, and TPACK. The findings provide essential theoretical insights and empirical support for improving knowledge sharing practices among primary and secondary school teachers, thereby advancing high quality professional development.

Theoretically, this study enhances the comprehension of gender as a moderating variable in the relationship between knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK development, extending the frameworks of social capital theory and knowledge management theory. The findings reveal that male teachers can leverage social-technical capital more effectively to achieve notable improvements in TPACK, highlighting the critical role of gender in digital education transformation. Moreover, this study underscores the multifaceted value of teachers’ knowledge sharing in the context of digital technology, enriching the theoretical understanding of TPACK development and offering new directions for future research on the interaction between gender and social-technical capital.

Practically, this study provides several actionable recommendations. Educators should actively leverage digital tools to engage in bidirectional knowledge-sharing activities, balancing the absorption of external expertise with proactive contributions of their specialized insights, thereby fostering a dynamic exchange of pedagogical and technological knowledge. School leaders must model digital engagement by participating in frontline teaching practices and establishing robust feedback mechanisms, such as timely recognition through platform comments or personalized acknowledgments, to cultivate an organizational culture rooted in openness, inclusivity, and collaboration. Policymakers should design tiered incentive strategies that integrate intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, tailored to career-stage differences: guiding novice teachers through low-barrier tasks like resource reviews, embedding metrics such as resource downloads and citations into professional evaluations for mid-career teachers, and providing expert teachers with dedicated funding to amplify innovative practices. This is not only essential for improving the quality of basic education in China’ s primary and secondary schools but also for cultivating a high-caliber teaching workforce capable of meeting the requirements of the new age.

In addition, this study has several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causation. Future research should adopt a longitudinal design to examine these relationships over time. Second, although this study collected national data with a large sample size, its sample representativeness is still limited. In particular, the sample includes a relatively small proportion of male teachers compared to female teachers. Future studies should aim to increase male teacher representation to more thoroughly investigate gender differences in the relationship between teachers’ knowledge sharing behavior and TPACK in the digital age.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Ahmed YA, Ahmad MN, Ahmad N et al. (2019) Social media for knowledge sharing: a systematic literature review. Telemat. Inf. 37:72–112

Akhavan P, Mahdi HS (2016) Social capital, knowledge sharing, and innovation capability: an empirical study of R&D teams in Iran. Technol. Anal. Strateg Manag 28(1):96–113

Bhandari H, Yasunobu K (2009) What is social capital? a comprehensive review of the concept. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 37(3):480–510

Bingimlas K (2018) Investigating the level of teachers’ knowledge in technology, pedagogy, and content (TPACK) in Saudi Arabia. South Afr. J. Educ. 38(3):1–12

Blank G, Groselj D (2014) Dimensions of internet use: amount, variety, and types. Inf. Commun. Soc. 17(4):417–435

Boschman F, McKenney S, Voogt J (2015) Exploring teachers’ use of TPACK in design talk: the collaborative design of technology-rich early literacy activities. Comput Educ. 82:250–262

Bélisle C (2006) Literacy and the digital knowledge revolution. In: Digital literacies for learning Facet, p. 51-67

Carlson A, Isaacs AM (2018) Technological capital: an alternative to the digital divide. J. Appl Commun. Res 46(2):243–265

Cetin-Dindar A, Boz Y, Sonmez DY et al. (2018) Development of pre-service chemistry teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge. Chem. Educ. Res Pr. 19(1):167–183

Chai CS, Koh JHL, Ho HNJ et al. (2012) Examining preservice teachers’ perceived knowledge of TPACK and cyber wellness through structural equation modeling. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 28(6):1000–1019

Chai S, Das S, Rao HR (2011) Factors affecting bloggers’ knowledge sharing: an investigation across gender. J. Manag Inf. Syst. 28(3):309–342

Chiu CM, Hsu MH, Wang ET (2006) Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: an integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 42(3):1872–1888

Choi JH, Ramirez R, Gregg DG et al. (2020) Influencing knowledge sharing on social media: a gender perspective. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 30(3):513–531

Cummings JN (2004) Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Manag. Sci. 50(3):352–364

Deng F, Lan W, Sun D, Zheng Z (2023) Examining pre-service chemistry teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) of using data-logging in the chemistry classroom. Sustainability 15(21):15441

Deng H, Duan SX, Wibowo S (2023) Digital technology-driven knowledge sharing for job performance. J. Knowl. Manag 27(2):404–425

Durand F, Bourgeault IL, Hebert RL, Fleury MJ (2022) The role of gender, profession, and informational role self-efficacy in physician–nurse knowledge sharing and decision-making. J. Interprof. Care 36(1):34–43

Eslami MH, Achtenhagen L, Bertsch CT, Lehmann A (2023) Knowledge-sharing across supply chain actors in adopting Industry 4.0 technologies: an exploratory case study within the automotive industry. Technol. Forecast Soc. Change 186:122118

Fabian A, Fütterer T, Backfisch I et al. (2024) Unraveling TPACK: investigating the inherent structure of TPACK from a subject-specific angle using test-based instruments. Comput Educ. 217:105040

Goktan AB, Gupta VK (2015) Sex, gender, and individual entrepreneurial orientation: evidence from four countries. Int J. Entrep. Manag J. 11(1):95–112

Grubic-Nesic L, Matic D, Mitrovic S (2015) The influence of demographic and organizational factors on knowledge sharing among employees in organizations. Teh.čki Vjesn.-Tech. Gaz. 22(4):1005–1011

Hau YS, Kim B, Lee H, Kim YG (2013) The effects of individual motivations and social capital on employees’ tacit and explicit knowledge sharing intentions. Int J. Inf. Manag 33(2):356–366

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press

He Z, He J, Niu J (2023) An empirical study on the mechanism of human capital, social capital, and gender differences: based on the sample of interpersonal relationship network survey. Jianghan Trib. 04:36–42

Huang X, Li H, Huang L, Jiang T (2023) Research on the development and innovation of online education based on digital knowledge sharing community. BMC Psychol. 11(1):295

Jackson SE, Chuang CH, Harden EE et al. (2006) Toward developing human resource management systems for knowledge-intensive teamwork. In: Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p 27-70

Jang SJ, Tsai MF (2012) Exploring the TPACK of Taiwanese elementary mathematics and science teachers with respect to use of interactive whiteboards. Comput Educ. 59(2):327–338

Kim S, Ju B (2008) An analysis of faculty perceptions: attitudes toward knowledge sharing and collaboration in an academic institution. Lib. Inf. Sci. Res 30:282–290

Koehler MJ, Mishra P (2005) What happens when teachers design educational technology? the development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. J. Educ. Comput Res 32(2):131–152

Koh JHL, Divaharan H (2011) Developing pre-service teachers’ technology integration expertise through the TPACK-developing instructional model. J. Educ. Comput Res 44(1):35–58

Lepore D, Dubbini S, Micozzi A et al. (2021) Knowledge sharing opportunities for Industry 4.0 firms. J Knowl Econ 1-20

Li H, Wang W (2021) Why share knowledge? an analysis of the influencing factors of knowledge sharing in virtual learning communities based on systematic literature review [in Chinese]. China Distance Educ. 11:38–47

Li H, Zhang R, Duan J (2023) Research on the influencing factors of online continuous knowledge sharing intention based on meta-analysis. J. Inf. Sci. 01:49–60

Lin CP, Huang HT, Huang TY (2020) The effects of responsible leadership and knowledge sharing on job performance among knowledge workers. Pers. Rev. 49(9):1879–1896

Lin TC, Tsai CC, Chai CS et al. (2013) Identifying science teachers’ perceptions of technological pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK). J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 22:325–336

Lu HP, Lee MR (2012) Experience differences and continuance intention of blog sharing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 31(11):1081–1095

Ma W, Baek J (2020) The Technology-Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge differences between pre-service and in-service teachers and the related effects of gender interaction in China. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 11(11):353–359

Malik MS, Kanwal M (2018) Impacts of organizational knowledge sharing practices on employees’ job satisfaction: mediating roles of learning commitment and interpersonal adaptability. J. Workplace Learn 30(1):2–17

Mouza C (2003) Learning to teach with new technology: implications for professional development. J. Res Technol. Educ. 35(2):272–289

Mura M, Lettieri E, Radaelli G et al. (2016) Behavioural operations in healthcare: a knowledge sharing perspective. Int J. Oper. Prod. Manag 36(10):1222–1246

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag Rev. 23(2):242–266

Nonaka I, Takeuchi H (1995) The knowledge-creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press

Olan F, Arakpogun EO, Suklan J et al. (2022) Artificial intelligence and knowledge sharing: contributing factors to organizational performance. J. Bus. Res 145:605–615

Özbebek A, Toplu EK (2011) Empowered employees’ knowledge sharing behavior. Int J. Bus. Manag Stud. 3(2):69–76

Palacios-Marquéz D, Peris-Ortiz M, Merigó JM (2013) The effect of knowledge transfer on firm performance: an empirical study in knowledge-intensive industries. Manag Decis. 51:973–985

Perotti FA, Rozsa Z, Kuděj M, Ferraris A (2024) Building a knowledge sharing climate amid shadows of sabotage: a microfoundational perspective into job satisfaction and knowledge sabotage. J. Knowl. Manag 28(5):1490–1516

Pierson ME (2001) Technology integration practice as a function of pedagogical expertise. J. Res Comput Educ. 33(4):413–430

Prestridge S (2019) Categorising teachers’ use of social media for their professional learning: a self-generating professional learning paradigm. Comput Educ. 129:143–158

Pulakos ED (2003) Hiring for knowledge-based competition. In: Managing knowledge for sustained competitive advantage: designing strategies for effective human resource management. Jossey-Bass, p 1-19

Ragnedda M, Ruiu ML, Addeo F (2019) Measuring digital capital: an empirical investigation. N. Media Soc. 21(6):146144481986960

Ramachandran SD, Chong SC, Ismail H (2009) The practice of knowledge management processes: a comparative study of public and private higher education institutions in Malaysia. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag Syst. 39:203–222

Ramayah T, Yeap JA, Ignatius J (2014) Assessing knowledge sharing among academics: a validation of the knowledge sharing behavior scale (KSBS). Eval. Rev. 38(2):160–187

Ramayah T, Yeap JAL, Ignatius J (2013) An empirical inquiry on knowledge sharing among academicians in higher learning institutions. Minerva 51:131–154

Ranieri M, Manca S, Fini A (2012) Why (and how) do teachers engage in social networks? Educ. Media Int 49(4):267–282

Resnick M (2002) Rethinking learning in the digital age. The MIT Press

Scherer R, Tondeur J, Siddiq F (2017) On the quest for validity: testing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the technology-dimensions in the Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge (TPACK) model. Comput Educ. 112:1–17

Schmidt DA, Baran E, Thompson AD et al. (2009) Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): the development and validation of an assessment instrument for preservice teachers. J. Res Technol. Educ. 42(2):123–149

Shulman LS (1986) Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res 15(2):4–14

Swanson E, Kim S, Lee SM et al. (2020) The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: social capital theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag 42:88–96

Thakadu OT (2018) Communicating in the public sphere: effects of patriarchy on knowledge sharing among community-based organizations leaders in Botswana. Environ. Dev. Sustain 20:2225–2242

Tondeur J, Scherer R, Siddiq F, Baran E (2017) A comprehensive investigation of TPACK within pre-service teachers’ ICT profiles: mind the gap! Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 36(3):151–172

Treem JW, Leonardi PM (2012) Social media use in organizations: exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Commun. Yearb. 36:143–189

Vanden HB, De RJA (2004) Knowledge sharing in context: the influence of organizational commitment, communication climate, and CMC use on knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag 8(6):117–130

Voogt J, Fisser P, Tondeur J et al. (2016) Using theoretical perspectives in developing an understanding of TPACK. In: Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) for educators. Routledge, p 33-52

Wang S, Noe RA (2010) Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag Rev. 20(2):115–131

Wang Z, Wang N (2012) Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Syst. Appl 39(10):8899–8908

Williams D (2006) On and off the ‘Net: Scales for social capital in an online era. J. Comput Mediat Commun. 11(2):593–628

Xu X, Liu F (2023) The impact of social capital and technological support on knowledge sharing in academic virtual communities: an analysis of knowledge sharing elements based on the Science Net platform [in Chinese]. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 03:122–131

Yan G, Tian R, Xiong Z, Sun L (2019) Review of the “digital gender gap” in the 5G era: Causes and solutions - Insights from the OECD report “Closing the Digital Gender Gap. J. Distance Educ. 05:66–74

Yeh YC, Yeh YL, Chen YH (2012) From knowledge sharing to knowledge creation: A blended knowledge-management model for improving university students’ creativity. Think. Skills Creat 7(3):245–257

Yi J (2009) A measure of knowledge sharing behavior: scale development and validation. Knowl. Manag Res Pr. 7(1):65–81

Zhang W (2024) Bridging the gender digital divide: triple issues and governance paths for women’s digital development in developing countries [in Chinese]. Mod. Commun. (J. Commun. Univ. China) 03:35–43

Zhang X, Venkatesh V (2013) Explaining employee job performance: the role of online and offline workplace communication networks. MIS Q 695-722

Zhao L, Lu Y, Wang B et al. (2012) Cultivating the sense of belonging and motivating user participation in virtual communities: a social capital perspective. Int J. Inf. Manag 32(6):574–588

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the 2023 China Ministry of Education’s Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Project, “Construction and Measurement of Teacher Collaboration Competence Indicators in the Digital Age” (23YJC880005), and by the General Project of Scientific Research, Department of Education of Liaoning Province, “Construction and Application of Evaluation Index System of Organized Scientific Research in Local Universities of Liaoning Province” (LJ112410165030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY was responsible for research design and literature review; ZW for drafting the initial manuscript; WS for the critical manuscript revision and translation; and SN for data collection and analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Liaoning Normal University (Approval No. LL2025004) on January 2, 2025. All procedures performed in this study adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained to protect their privacy throughout the research process.

Informed consent

Children and minors were not included as participants in this study. Prior to completing the questionnaire, investigators provided participants with clear and comprehensive information regarding the nature, objectives, and potential risks of the study, as outlined in the questionnaire instructions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants on January 3, 2025, who were explicitly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. All personal information and data collected were kept strictly confidential and used solely for academic research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, S. et al. Teachers’ knowledge sharing behaviors and TPACK in the digital age: the roles of gender and social-technical capital. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05843-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05843-3