Abstract

Shame and guilt are critical self-conscious emotions that influence psychological well-being. The Personal Feelings Questionnaire-2 (PFQ-2) is a widely used to assess these emotions, yet its psychometric properties within Arab populations remain underexplored. Additionally, psychological distress may mediate the relationships between resilience, religiosity, and emotional outcomes. This study examined the psychometric properties of the PFQ-2 among Libyan and Emirati Arab populations to assess shame and guilt. A total of 281 participants from Libya and the UAE completed self-report measures of shame and guilt (PFQ-2), resilience (Brief Resilience Scale), religiosity (Muslim Religiosity Scale), and psychological distress (DASS-8). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported a two-factor structure (χ2 (76) = 101, p = 0.028, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.059), with the exclusion of two low-performing items “Disgusting to others” and “Laughable” improving model fit. Internal consistency was satisfactory for both shame (α = 0.80, ω = 0.80) and guilt (α = 0.84, ω = 0.85). Structural equation modeling indicated that psychological distress significantly mediated the negative associations between resilience and shame (β = −0.09, p = 0.004), and between extrinsic religiosity and shame (β = −0.06, p = 0.016). Gender and cultural differences emerged, with females reporting higher guilt than males (Mean Difference = 1.84, p = 0.041), and Libyan participants exhibiting higher levels of guilt (Mean Difference = 2.18, p = 0.016) and shame (Mean Difference = 2.76, p = 0.012) compared to Emirati participants. Post-hoc analysis revealed that Libyan females reported significantly higher guilt than UAE males (Mean Difference = 4.03, p = 0.039), whereas gender differences in shame were nonsignificant (F (1,28) = 0.008, p = 0.93). The findings underscore the importance of culturally sensitive assessments and highlight psychological distress as a key factor in understanding resilience and religiosity in emotional well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shame and guilt are complex emotional experiences that play significant roles in shaping human behavior and psychological well-being (Tangney et al., 2011). These emotions, while overlapping in some respects, are distinct constructs associated with different cognitive processes and emotional outcomes (Tangney and Dearing, 2002). Shame typically involves a negative self-evaluation, often related to a perceived failure to meet social or personal standards, whereas guilt focuses on specific actions perceived as morally wrong (Lewis, 1971; Tangney et al., 2002; Tracy and Robins, 2006).

Guilt, shame, resilience, and religiosity

Guilt and shame relationships with resilience and religiosity further highlight the interplay between emotional and cognitive processes in shaping psychological responses (Dorahy et al., 2013; Sawai et al. 2017). Prior research has demonstrated that higher levels of shame correlate with lower resilience, suggesting that shame-prone individuals struggle with adaptive coping mechanisms (Kaplánová and Gregor, 2021; Flach & Cariola, 2025; Hasui et al., 2009). However, shame resilience, defined as an individual’s ability to process and recover from shame, has been associated with improved subjective well-being (Arnink, 2020; Brown, 2006). Guilt repair, defined as a reparative response to guilt, exhibits a weaker, yet significant negative correlation with resilience, suggesting that engaging in reparative behaviors might slightly decrease resilience (Kaplánová and Gregor, 2021). Interestingly, some studies suggest that guilt may not have a significant relationship with resilience (Hasui et al., 2009, Van Vliet, 2008; Orhan et al., 2025).

Moreover, both shame and guilt were positively correlated with religiosity, indicating that individuals who experience higher levels of these emotions might also report stronger religious engagement or values (Sawai et al., 2017; Kim-Prieto and Diener, 2009; Varghese, 2015; Van Cappellen et al., 2016). This connection is particularly evident in positive religious coping, which involves faith-based strategies, such as prayer and community support, to mitigate distress and enhance psychological well-being (Freeman, 2018; Pargament et al., 1998). Religious coping is linked to increased guilt repair and shame withdrawal but is negatively associated with shame-related negative self-evaluation.

Psychological distress as a mediator

Psychological distress, broadly defined as the experience of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, plays a pivotal role in understanding the effects of shame and guilt (Kim et al., 2011; Bilevicius et al., 2018; Arditte et al., 2016; Espinosa da Silva et al., 2022; Etemadi Shamsababdi and Dehshiri, 2024). Importantly, psychological distress function as a central mediator in the relationship between various protective or risk factors (e.g., social support, trauma) and mental health outcomes (Yıldız and Yüksel, 2024; Acoba, 2024). Prior research highlights its significant role in explaining how protective factors like resilience and religiosity influence mental health. For instance, resilience indirectly reduces the impact of traumatic experiences on depression and anxiety through its buffering effect on distress (Ali et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2015; Poole et al., 2017). Similarly, religiosity, particularly extrinsic motivations motivational components (e.g., engaging in religious practices for social affiliation or external validation), may mitigate indirectly emotional distress by fostering coping mechanisms and social support (Koenig et al., 2012; Moreira-Almeida et al., 2014; Lucchetti et al., 2021; Giannoulis and Giannouli, 2020). Thus, examining the mediating role of psychological distress is critical in understanding how individuals navigate the interplay of emotional experiences like shame and guilt with broader psychological and cultural factors such as resilience and religious orientation.

The role of culture and psychometric validation

Understanding the interplay of shame, guilt, and psychological distress within diverse cultural and demographic contexts is critical. Cross-cultural studies indicate significant variations in emotional expressions, with cultural norms shaping how individuals experience and regulate shame and guilt (Kitayama et al., 1997; Fischer and Manstead, 2000; Fischer et al., 2004). Gender differences further complicate this landscape, as women tend to report higher levels of shame and guilt compared to men, with women often reporting higher levels of these emotions (Else-Quest et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2004; Sawai et al., 2017; Ferguson et al., 2000; Lutwak and Ferrari, 1996). Given these complexities, psychometric validation of instruments that measure shame and guilt within specific cultural contexts is essential.

In response to this need, the measurement of shame and guilt has advanced through the development of psychometrically validated instruments. Tools like the Personal Feelings Questionnaire-2 (PFQ-2) and the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) are widely used for assessing these emotions. Validation studies have exhibited their utility in distinguishing between shame and guilt while maintaining reliability and cultural adaptability (Harder and Zalma, 1990; Tangney et al.,1992; Rüsch et al., 2007; Lutwak and Ferrari, 1996; Espinosa da Silva et al., 2022). Furthermore, recent advancements in psychometrics, such as factor analysis and Item Response Theory (IRT), have enabled researchers to explore the dimensionality and validity of emotional constructs such as PFQ-2 with greater precision (Bond and Fox, 2015).

Study aims and hypotheses

Therefore, this study aims to (1) validate the PFQ-2 in Libyan and Emirati Arab populations and (2) examine whether psychological distress mediates the relationships between resilience, religiosity, and the emotional outcomes of shame and guilt. Employing advanced statistical techniques such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Item Response Theory (IRT), the study will investigate the unique contributions of resilience and religiosity in predicting shame and guilt within a culturally relevant framework.

The primary hypotheses are:

H1: We hypothesize that confirmatory factor analysis will support a two-factor structure, with shame and guilt items loading predominantly onto separate factors.

H2: Higher resilience will be negatively associated with psychological distress, shame, and guilt.

H3: Psychological distress will mediate the relationships between resilience, religiosity, and the emotional outcomes of shame and guilt.

Methodology

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of 281 participants with a mean age of 24.38 years (SD = 7.81), ranging from 18 to 54 years. In terms of gender distribution, 74.02% of the participants were female (n = 208), and 25.98% were male (n = 73). Regarding nationality, the majority of the participants were Libyan (76.51%, n = 215), while 23.49% were from the UAE (n = 66). For educational attainment, 8.90% of participants had completed high school (n = 25), 79.72% were university graduates (n = 225), and 11.03% had completed postgraduate studies (n = 31).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants were eligible to take part in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18 years or older (2) able to read and understand Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), which is the formal written and widely understood version of Arabic used across the Arab world in education, media, and official communication, and (4) provided informed consent to participate in the study. Individuals were excluded if they (1) reported a current or past diagnosis of a severe psychiatric disorder that could impair their ability to complete the self-report measures reliably, or (2) failed to complete all the questionnaire items.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) and the official websites of various Libyan and UAE communities and universities, using convenience and snowball sampling methods. The online questionnaire was accessible from July 28 to October 20, 2024. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, with confidentiality and privacy were rigorously maintained.

In line with the principles of quantitative research, all measures were self-administered in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), and data were collected through an automated online platform. The researcher had no direct interaction with participants during the data collection process, thereby ensuring objectivity and detachment from the measurement process. This approach ensured that the instruments functioned independently of researcher influence, preserving the validity and reliability of responses.

The research protocol received approval from the researcher’s Institutional Review Board, under reference number MMST/2/1/25 M, reflecting a commitment to ethical standards, transparency, and integrity throughout the research process.

Measures

A demographics questionnaire was administered to gather basic background information from each participant, including age, gender, education, and country of origin.

Personal Feelings Questionnaire 2 (PFQ-2 Brief)

The Arabic-translated PFQ-2 questionnaire was used for assessing shame and guilt proneness (Harder and Greenwald, 1999). PFQ-2 consists of 16 items on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (continuously or almost constantly). This measurement contains 10 items assessing shame-proneness (e.g., “feeling humiliated, embarrassed; feelings of blushing”) and 6 items assessing guilt-proneness (e.g., “intense guilt, remorse, regret”) using 5-point Likert-type responses (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = some of the time, 3 = frequently but not continuously, 4 = continuously or almost continuously. A summed score was calculated from item responses, with higher scores indicating greater levels of shame (range = 0–40) and guilt (range = 0–24). The shame and guilt demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.80; McDonald’s ω total = 0.80; Cronbach’s α = 0.84; McDonald’s ω total = 0.85).

Resilience

The Arabic version of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), developed by Baattaiah et al. (2023), is based on the original version by Smith et al. (2008). The BRS is a self-rated assessment used to quantify a person’s ability to bounce back from and cope with health-related stressors, aiming to measure one’s ability to thrive in the face of adversity. The BRS consists of six items with total scores ranging from 6 to 30. Sample items include statements such as “I am able to recover quickly from stressful experiences” and “I remain calm under pressure.” Participants rate each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74.

Religiosity

The 13-item Muslim Religiosity Scale (MRS) Arabic version, developed by Al Zaben et al. (2015), is a self-reported measure assessing two dimensions of religiosity through two subscales: religious practices and intrinsic religious beliefs. The religious practices subscale includes 10 items, such as “How often do you attend group religious services for worship and prayer at a mosque or in small groups at work or in your home (i.e., obligatory prayers).” The intrinsic religious beliefs subscale consists of 3 items, such as “My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life.” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The MRS demonstrates acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values for religious practices (α = 0.60), intrinsic religious beliefs (α = 0.62), and the overall scale (α = 0.60).

Psychological distress

Participants in this samples also completed the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-8) in Arabic. This self-administered tool, developed by Ali et al. (2022), assesses symptoms related to depression, anxiety, and stress. The scale comprises 3 items for anxiety, 3 for depression, and 2 for stress. Sample items include “I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything” (depression), “I found it difficult to relax” (stress), and “I felt scared without any good reason” (anxiety). Participants rated the applicability of each item on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“applied to me most of the time”). Total scores were computed by summing all item scores and dividing the total by two. Higher scores on the scale indicate a greater severity of symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Reliability analysis showed satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from depression α = 0.60, anxiety 0.64, and stress = 0.50 and α = 0.79 for the overall scale, affirming its reliability in measuring stress, anxiety, and depression.

Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the study population’s age, sex, education level, and country. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, while frequencies were reported for categorical variables.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

CFA was conducted to examine the intercorrelations among the items and to determine if the PFQ-2 shame and guilt subscales exhibited an underlying two-factor structure. Due to the ordinal nature of the item response options, CFA for ordinal data was applied (Li, 2016) using the CFA function in the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) within the JASP statistical software. As model assumptions were violated, model fit was evaluated using diagonally weighted least squares estimation for the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI). An acceptable fit was indicated by RMSEA values below 0.10 and CFI and TLI values above 0.90.

Item performance

To examine item-level properties within the scale, Item Response Theory (IRT) was applied using the Partial Credit Model (PCM) (Wright and Masters, 1997), suitable for polytomous items with ordered response categories. PCM, an extension of the Rasch model, estimates individual threshold parameters for each item, capturing the difficulty of transitioning between response categories.

In PCM, the delta-tau parameterization was used to interpret item thresholds. Each item has a series of threshold (tau) parameters representing the points along the latent trait continuum where respondents are equally likely to choose between adjacent categories (Andrich, 2013). Items with evenly spread thresholds demonstrate an effective range across the trait continuum, while items with compact thresholds may cluster within a narrow range of the trait. Each item has four tau parameters (τ1, τ2, τ3, τ4) representing the thresholds for moving from one category to the next, typically across a Likert-type scale (e.g., from “Not at all” to “Very much”).

Model fit was evaluated through Infit and Outfit statistics (Pina et al., 2005). These statistics, represented as mean square (MNSQ) values, assess the degree to which item responses align with model expectations: Infit: Information-weighted, capturing how well an item fits when responses are near the person’s trait level. Outfit: Sensitive to outliers, capturing unexpected responses that deviate from expected patterns. Following Linacre (2002), ideal Infit and Outfit values range between 0.7 and 1.3 for acceptable fit. Values below 1 indicate overfit, suggesting items may be too predictable, while values above 1.3 indicate underfit, suggesting items may be noisy or misaligned with the primary construct.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω total, and ω hierarchical. Cronbach’s α, despite limitations, such as its assumption of tau-equivalence, which may lead to underestimations in congeneric scales (McNeish, 2018; Sijtsma, 2009), was included for comparison with prior studies, given its widespread use. However, α can inflate reliability estimates when scales have many or redundant items (Streiner, 2003). In contrast, McDonald’s ω total and ω hierarchical provide a more accurate estimate of reliability for multidimensional scales, as they account for variance due to a primary general factor and specific factors (Revelle and Zinbarg, 2009). All reliability coefficients were calculated using the omega function in the JAMUVI statistical package.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was evaluated by correlating the PFQ-2 shame and guilt subscales with depression, anxiety, stress (DASS-8), and resilience (Resilience Scale), while discriminant validity was assessed with religiosity subscales. All analyses were conducted using JAMOVI (Version 3.6.1), JASP, and SAS (Version 9.4).

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

We utilized SEM to examine the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between resilience, extrinsic and intrinsic religiosity, and the outcomes of guilt and shame. In the study model, resilience and both religiosity subscales served as the independent variables, psychological distress was the mediating variable, and guilt and shame were the dependent variables. Key indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI), all fit values, significantly exceed the standard 0.95 cutoff for a good fit. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values and below 0.10, indicating minimal residual error and aligning with ideal fit criteria. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and McDonald Fit Index (MFI) further confirm an outstanding model fit above 0.90 is generally considered acceptable (McDonald and Ho, 2002).

Results

Power analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted to determine the sensitivity of the design in detecting meaningful effect sizes. Given a sample size of 20 participants per group, the test achieves a statistical power of 0.90 to detect effect sizes of |δ | ≥ 1.05 at a significance level of α = 0.05. This indicates that the study is well-powered to reliably identify large effects but may struggle with detecting smaller ones.

The sensitivity of the test across varying effect sizes is illustrated in the power-by-effect-size table. Specifically, effects below |δ | = 0.64 have a detection probability of 50% or less, indicating a high likelihood of Type II error. Moderate effects (0.64 < |δ | ≤ 0.91) have a detection probability between 50% and 80%, suggesting a reasonable chance of missing effects of this magnitude. In contrast, effect sizes exceeding |δ | = 0.91 are likely to be detected with high probability (80–95%), and those larger than |δ | = 1.17 are almost surely detected ( ≥95%).

The accompanying power contour and power curve plots further illustrate the relationship between sample size and sensitivity. The contour plot in Fig. 1 shows that increasing sample size would enhance the ability to detect smaller effects reliably. Conversely, maintaining the current sample size ensures sufficient sensitivity only for larger effects. The power curve in Fig. 2 reinforces this conclusion, highlighting that the chosen design is optimally suited for detecting strong effects while being limited in sensitivity to smaller effect sizes.

Confirmatory factor analysis models

Model 1 Results

In the first model, the chi-square statistic was significant, χ2 (103) = 215, p < 0.001, indicating a poor fit. The baseline model also showed a significant chi-square statistic, χ2 (120) = 3292, p < 0.001. The fit indices for this model revealed a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.074 (90% CI: 0.062–0.074, p = 0.041) and a Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of 0.074. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.97, and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.96, both indicating acceptable model fit, albeit not optimal. Given that Mardia’s coefficients indicated a violation of normal distribution (Skewness = 18.9, Kurtosis = 237.3, p < 0.001), we applied the Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimator to account for this deviation.

Model 2 Results

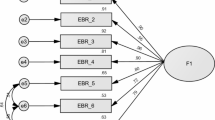

In the second model, which excluded items Shame-9 (“Disgusting to others”) and Shame-10 (“Laughable”) due to their low factor loading (less than 0.30), the fit significantly improved. The chi-square statistic was χ2(76) = 101, p = 0.028, which, while still significant, showed better fit compared to the first model. The baseline model for the second model also maintained significance, χ2(91) = 3132, p < 0.001. The fit indices demonstrated a notable improvement, with an RMSEA of 0.059 (90% CI: 0.035–0.051, p = 0.94) and an SRMR of 0.059. The CFI improved to 0.99, and the TLI reached 0.99, both suggesting an excellent fit for the second model.

Additionally, the R2 values for items Shame −9 “Disgusting to others” and Shame-10 “Laughable” were notably low, at 0.038 and 2.65 × 10⁻⁵, respectively, further supporting their exclusion from the model. Overall, the exclusion of items S9 and S10 in the second model led to enhanced model fit, demonstrating that these items did not contribute meaningfully to the underlying factor structure (See Fig. 3).

The reliability indices for the final model indicated acceptable internal consistency for both constructs. For the Shame variable, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.80, with ω₁ = 0.80, ω₂ = 0.80. For the Guilt variable, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was 0.84, with ω₁ = 0.85.

Item response theory (IRT) and model fit results

To better understand how individuals respond to varying levels of shame or guilt, we applied the Partial Credit Model (PCM), a method that estimates item difficulty across multiple response categories. Specifically, the delta-tau framework identifies “thresholds” for each item, points along the trait spectrum (e.g., shame-proneness) where a respondent becomes equally likely to choose between two adjacent response options. These thresholds help indicate which items are most sensitive to different levels of emotional experience.

For example, the item Humiliated demonstrates increasing response difficulty at higher trait levels, with the most notable shift occurring between the third and fourth category (τ3 = 0.3735, τ4 = 0.720). This pattern suggests that individuals with moderate social discomfort may experience challenges endorsing extreme responses. Conversely, Embarrassed presents more extreme thresholds (τ1 = −1.213, τ4 = 1.000), indicating that lower-trait respondents predominantly endorse the minimal response categories, while higher-trait individuals encounter greater difficulty moving to elevated categories.

Threshold values for items such as Disgusting to others and Laughable are more compact (e.g., τ1 = −0.484, τ4 = 0.840), suggesting smoother progression across response levels. This may indicate more consistent endorsement patterns across individuals with varying trait levels. Full threshold parameters for all items are presented in Table 1, allowing for detailed comparisons.

Infit and Outfit statistics further evaluate item fit to the latent trait model. Items such as Humiliated (Infit = 0.843, Outfit = 0.841) and Ridiculous (Infit = 0.900, Outfit = 0.908) show good fit, aligning well with expected response patterns. However, items like Self-consciousness (Infit = 0.828, Outfit = 0.823) and Embarrassed (Infit = 0.661, Outfit = 0.662) exhibit overfit, suggesting they may be highly predictable based on latent trait levels.

Conversely, Laughable (Infit = 1.477, Outfit = 1.527) has high misfit values, indicating unexpected responses or potential noise. Disgusting to others (Infit = 1.187, Outfit = 1.198) shows mild misfit yet retains interpretive value. These findings align with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results, supporting a nuanced evaluation of item contributions to the scale.

Concurrent validity

Bivariate correlations provide validity evidence, showing a strong association between shame and guilt, supporting concurrent validity, while resilience’s negative correlation with both constructs reflects discriminant validity. Emotional distress variables further reinforce convergent validity, with distinct correlation patterns for shame and guilt. All statistical details are presented in Table 2.

Mediation and prediction

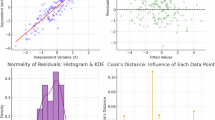

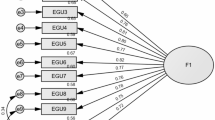

To explore the mediating role of psychological distress, we used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a technique suited for analyzing complex interrelations among variables. Given the significant violation of multivariate normality, as indicated by Mardia’s coefficients (Skewness = 6.143, χ2 = 287.674, df = 56, p < 0.001; Kurtosis = 52.340, z = 3.713, p < 0.001)—we applied the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, which is robust to non-normal data and appropriate for ordinal scales. After this adjustment, the model fit indicators suggested excellent alignment between the hypothesized and observed data, with the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.99), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI = 0.99), and Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI = 0.97), all indicate perfect fit values, far surpassing the typical cutoff of 0.95 for good model fit. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.035) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.063) are both exceptionally low, suggesting minimal residual error and aligning with ideal fit standards. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI = 0.98) and McDonald Fit Index (MFI = 0.96) further support the model’s strong fit to the data. Finally, the low Expected Cross Validation Index (ECVI = 0.57) implies good generalizability.

Mediation and regression analyses emphasize the protective role of resilience and extrinsic religious motivation in reducing distress-related shame, while intrinsic religious belief shows no significant effects. Regression findings confirm Total DASS as a predictor of shame but not guilt, highlighting resilience’s strong inverse relationship with both emotions. A summary of statistical estimates is provided in Fig. 4.

Structural equation model (SEM) illustrating the relationships between resilience (Rsl), intrinsic religious belief (Int), extrinsic religious practices (Ext), psychological distress (TDA), shame (Shm), and guilt (Glt). Significant direct effects are indicated in bolded paths, while non-significant paths are not bolded. Mediation effects are highlighted in red.

Gender difference in study variables

The results indicate significant effects of gender and country on guilt, with females reporting higher guilt than males and Libyan participants experiencing greater guilt than those from the UAE. An interaction between gender and country reveals that Libyan females report higher guilt than UAE males, though guilt levels among females are consistent across both countries. For shame, there is no significant gender difference, but Libyan participants report higher shame than those from the UAE. Resilience shows a gender effect, with females scoring lower than males, though country differences are not significant. Intrinsic motivation is significantly higher among males, while extrinsic motivation does not show significant effects but trends toward country-level differences. Depression and anxiety are significantly higher among Libyan participants, with no gender effects, though interaction effects suggest nuanced relationships worth further exploration. Stress shows significant differences based on gender and country, with females and Libyan participants reporting higher levels. Full statistical details are presented in the corresponding Tables 3 and 4.

Discussion

The findings of this study confirm the psychometric validity and reliability of the PFQ-2 in assessing shame and guilt within Libyan and Emirati Arab populations. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported a two-factor structure, with shame and guilt items loading predominantly onto separate factors, reinforcing prior research on their distinctiveness (Tangney et al., 1992; Rüsch et al., 2007). The exclusion of low-performing items, “Disgusting to others” and “Laughable”, significantly improved model fit, underscoring the importance of cultural adaptability in psychometric evaluations (Espinosa da Silva et al., 2022).

These items may have underperformed due to linguistic or conceptual differences in how shame and guilt are experienced and expressed within Arab cultural frameworks. In collectivist societies, shame is often tied to social reputation and family honor rather than purely individual self-perceptions (Gharaibeh, 2017; Beddi et al., 2020). The item Disgusting to others may not resonate with respondents in the same way it does in Western contexts, where individual self-worth may be assessed through external validation. Similarly, Laughable might not carry strong connotations of moral or psychological distress in Arab cultures, as ridicule is often contextualized in humor or social dynamics rather than deeply internalized feelings of shame. The removal of these items ensures greater construct validity and cultural relevance, improving the scale’s applicability across diverse populations. Internal consistency for shame and guilt subscales was adequate, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.80 and 0.84, aligning with previous cross-cultural validations of the PFQ-2 (Harder and Zalma, 1990; Espinosa da Silva et al., 2022; Vigfusdottir et al., 2024; Rice et al., 2018).

The correlations between shame, guilt, resilience, psychological distress, and religiosity further support the scale’s validity. Resilience’s negative correlation with shame and guilt aligns with psychological frameworks highlighting resilience as a buffer against emotional distress (Kaplánová and Gregor, 2021; Flach & Cariola, 2025; Hasui et al., 2009). The stress-resilience model (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013) suggests that individuals with higher resilience engage in adaptive coping mechanisms that mitigate negative self-conscious emotions, reducing susceptibility to shame- and guilt-related distress.

Similarly, shame and guilt’s positive associations with psychological distress variables (depression, anxiety, and stress) reflect well-established links between self-conscious emotions and mental health outcomes (Kim et al., 2011; Bilevicius et al., 2018; Arditte et al., 2016; Espinosa da Silva et al., 2022; Etemadi and Dehshiri, 2024). The cognitive model of emotional regulation (Gross, 2002) posits that shame involves negative self-appraisal, making it particularly susceptible to anxiety and stress, whereas guilt though linked to distress can sometimes promote constructive behavioral responses (Tangney and Dearing, 2002).

Interestingly, our findings diverge from prior research on religiosity and guilt, where Luyten et al. (1998) found that religious individuals reported higher guilt levels, potentially due to moral sensitivity and increased awareness of ethical behavior. However, in some contexts, religiosity buffers maladaptive effects of shame, suggesting different pathways in how religious beliefs shape emotional experiences. In contrast, our study revealed no significant relationship between intrinsic religiosity and shame or guilt, possibly indicating that individuals with deeply internalized beliefs focus on personal growth rather than negative self-evaluation.

Furthermore, the mediation analysis highlighted the critical role of psychological distress in the relationships between resilience, religiosity, and the emotional outcomes of shame and guilt. Interestingly, resilience and extrinsic religious practices exhibited significant negative indirect effects on only shame through psychological distress, indicating that these protective factors reduce shame by mitigating distress levels. Notably, this aligns with the observed strong negative bivariate correlations between extrinsic religiosity, resilience and psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress, suggesting that resilience and social forms of extrinsic religious practices may serve as emotional buffers.

This pattern is further supported by broader literature linking resilience and religious coping to emotional well-being. Research highlight that resilience is more strongly associated with personal spiritual experiences, such as forgiveness, values-based beliefs, and private religious practices, than with institutional religious involvement (Koenig, 2012; Long, 2011). This distinction helps explain our findings, where resilience and extrinsic religiosity, possibly reflecting more socially supportive or emotionally expressive practices, was associated with reduced shame via lower psychological distress (Smith et al., 2015; Koenig et al., 2012; Yıldız and Yüksel, 2024; Acoba, 2024; Murray and Ciarrocchi, 2007; Giannoulis and Giannouli, 2020a, Giannouli, Giannoulis (2022); Carneiro et al., 2019; Lucchetti et al., 2021).

Interestingly, for guilt, the indirect effects of resilience, extrinsic religiosity, and intrinsic religiosity through psychological distress were not statistically significant. However, these effects suggest potential trends that are worth further exploration, particularly given the complex role of guilt within Arab Muslim cultural and religious frameworks. One possible explanation for the lack of significant indirect effects could be that guilt operates through more moral or existential processes than through distress alone (Baumeister et al., 1994; Boston et al., 2011), especially in the context of intrinsic religiosity, which is less tied to emotional regulation and more focused on personal moral reflection and spiritual development (Vishkin et al., 2014; McCullough and Willoughby, 2009; Ward and King, 2018). For individuals with high extrinsic religiosity, the guilt experience might be more tied to social expectations or fear of judgment, which could involve external sources of distress, rather than the internalized mechanisms measured here (Albertsen et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2011). Likewise, resilience, though negatively associated with distress, might not have been sufficient to mediate guilt, which is a more internalized and morally driven emotion in this cultural context. Thus, the absence of significant effects in these cases may reflect the distinct nature of guilt as a moral emotion that operates independently of distress or external religious practices in this sample.

The IRT analysis provided further insights into the performance of individual PFQ-2 items. Items such as “Humiliated” and “Ridiculous” demonstrated good fit, with infit and outfit values within acceptable ranges, suggesting their strong alignment with the underlying constructs of shame and guilt. In contrast, items “Disgusting to others” and “Laughable” exhibited poor fit, with compact tau thresholds and elevated outfit values, indicating their limited utility in capturing the latent traits. These findings reinforce the need for culturally sensitive modifications to psychometric instruments when applied in non-Western contexts (Bond and Fox, 2015).

Significant gender and cross-cultural differences were observed in the emotional and psychological variables examined. Females reported higher guilt levels than males, consistent with previous findings highlighting gendered differences in self-conscious emotions (Else-Quest et al., 2012; Fischer et al. in 2004; Sawai et al., 2017; Ferguson et al., 2000). The interaction between gender and country revealed that Libyan females exhibited the highest guilt scores, while UAE males reported the lowest, reflecting the influence of cultural norms on emotional experiences.

Shame scores showed significant cross-cultural differences, with Libyan participants reporting higher levels than their Emirati counterparts. However, no significant gender differences in shame were found, diverging from some prior studies. Resilience scores were higher among males than females in both countries. Libyan participants reported higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to UAE participants, likely due to prolonged exposure to conflict-related stressors, economic instability, and disruptions in social and community support systems (Ali et al., 2023; Abuhadra et al., 2023). These findings highlight the interplay of cultural and gender-specific factors in shaping psychological and emotional outcomes in Western culture (Kitayama et al. (1997); Fischer and Manstead, 2000; Fischer et al., 2004).

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the psychometric properties of the PFQ-2 and the mediating role of psychological distress, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationships between resilience, religiosity, psychological distress, and emotional outcomes. Future longitudinal studies are needed to establish the temporal dynamics of these variables and better understand their interplay over time. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures may introduce bias, such as social desirability or recall bias, which could affect the accuracy of the data. Incorporating multi-method approaches, including clinician-administered assessments or behavioral observations, may enhance the robustness of future findings. Additionally, some subscales used in the present study exhibited modest internal consistency (e.g., religious practices α = 0.60, intrinsic beliefs α = 0.62, stress α = 0.50), which may limit their reliability in capturing complex psychological constructs. While such values are considered acceptable in exploratory research and in culturally adapted, they underscore the need for ongoing psychometric refinement. These scales were primarily used to support convergent and discriminant validity assessments; nonetheless, future studies are encouraged to revalidate and recalibrate these measures to ensure stable and culturally resonant reliability coefficients across diverse Arab populations. Moreover, the sample was predominantly Libyan (76.5%), and the use of convenience and snowball sampling methods may have introduced selection bias and limited the generalizability of the findings across broader Arab populations. While this reflects contextual accessibility and cultural relevance, it may not fully capture regional nuances in the experience and expression of shame, guilt, or psychological distress. Future research should strive for more balanced sampling across Arab regions and adopt probability sampling techniques, such as stratified random sampling, to enhance representativeness and strengthen the external validity of the results.

Clinical implications

The findings of this study have important clinical implications for mental health interventions targeting shame, guilt, and psychological distress in Arab populations. First, the significant mediating role of psychological distress highlights the importance of addressing distress in therapeutic interventions. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) or mindfulness-based interventions that focus on reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress may indirectly alleviate feelings of shame and guilt. Moreover, resilience-enhancing strategies, such as strength-based counseling or resilience training programs, can serve as protective factors against distress and its emotional consequences.

Second, the observed associations between Extrinsic religiosity and emotional outcomes suggest that integrating culturally sensitive approaches, such as spiritual counseling or religious coping strategies, may be beneficial. For individuals with high extrinsic religiosity, fostering supportive religious communities or group-based religious activities could provide emotional and social support, reducing psychological distress and shame. However, the non-significant role of intrinsic religiosity in this study suggests that clinicians should carefully assess the individual’s religious orientation and tailor interventions accordingly.

Finally, the gender and cultural differences observed in shame, guilt, and distress underscore the need for gender-sensitive and culturally tailored interventions. For instance, Libyan participants, particularly females, reported higher levels of guilt and distress, highlighting the need for targeted interventions in this subgroup. Clinicians should consider the sociocultural and gender-specific factors influencing emotional well-being and design interventions that address these unique needs. Overall, this study emphasizes the importance of a holistic and culturally informed approach to mental health care in Arab populations.

Conclusion

This study underscores the robustness of the PFQ-2 in capturing shame and guilt within Arab cultural contexts, with strong evidence supporting its psychometric properties. The findings illuminate the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationships between resilience, religiosity, and emotional outcomes, offering valuable insights for culturally informed interventions. The observed gender and cross-cultural differences further emphasize the need for context-sensitive approaches to mental health assessment and intervention.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abuhadra BD, Doi S, Fujiwara T (2023) The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in Libya: a systematic review. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 30(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00322-4

Acoba EF (2024) Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Front Psychol 15:1330720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330720

Al Zaben F, Sehlo MG, Khalifa DA, Koenig HG (2015) Test–retest reliability of the Muslim religiosity scale: Follow-up to “religious involvement and health among dialysis patients in Saudi Arabia”. J Relig Health 54(3):1144–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0025-6

Albertsen EJ, O’Connor LE, Berry JW (2006) Religion and interpersonal guilt: variations across ethnicity and spirituality. Ment Health Relig Cult 9(1):67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13694670500040484

Ali AM, Hori H, Kim Y, Kunugi H (2022) The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-items expresses robust psychometric properties as an ideal shorter version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 among healthy respondents from three continents. Front Psychol 13:799769

Ali M, Altaeb H, Abdelrahman RM (2024) Resilience and religious coping in Libyan survivors of Hurricane Daniele. Clin Psychol Psychother 31(6):e70010. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.70010

Ali M, Veneziani G, Aquilanti I, Wamser-Nanney R, Lai C (2023) Overcoming the civil wars: the role of attachment styles between the impact of war and psychological symptoms and post-traumatic growth among Libyan citizens. Eur J Psychotraumatol 14(2):2287952. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2023.2287952

Andrich D (2013) An expanded derivation of the threshold structure of the polytomous Rasch model that dispels any “threshold disorder controversy”. Educ Psychological Meas 73(1):78–124

Arditte KA, Morabito DM, Shaw AM, Timpano KR (2016) Interpersonal risk for suicide in social anxiety: The roles of shame and depression. Psychiatry Res 239:139–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.017

Arnink CL (2020) A quantitative evaluation of shame resilience theory. Inq J 12(11). http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1806

Baattaiah BA, Alharbi MD, Khan F, Aldhahi MI (2023) Translation and population-based validation of the Arabic version of the brief resilience scale. Ann Med 55(1):2230887. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2230887

Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM, Heatherton TF (1994) Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychol Bull 115(2):243–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

Bilevicius E, Single A, Bristow LA, Foot M, Ellery M, Keough MT, Johnson EA (2018) Shame mediates the relationship between depression and addictive behaviours. Addict. Behav 82:94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.023

Bond TG, Fox CM (2015) Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences, 2nd edn. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315814698

Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R (2011) Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: an integrated literature review. J Pain Sympt Manag 41(3):604–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010

Brown B (2006) Shame Resilience Theory: A Grounded Theory Study on Women and Shame. Fam Soc 87:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3483

Carneiro ÉM, Navinchandra SA, Vento L, Timóteo RP, de Fátima Borges M (2019) Religiousness/spirituality, resilience and burnout in employees of a public hospital in Brazil. J Relig Health 58:677–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0691-2

Dorahy MJ, Irwin HJ, Middleton W (2013) Shame and guilt in the aftermath of childhood trauma. Clin Psychol Rev 33(6):620–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.04.001

Else-Quest NM, Higgins A, Allison C, Morton LC (2012) Gender differences in self-conscious emotional experience: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 138(5):947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930

Espinosa da Silva C, Pines HA, Patterson TL, Semple S, Harvey-Vera A, Strathdee SA, Smith LR (2022) Psychometric evaluation of the Personal Feelings Questionnaire–2 (PFQ-2) shame subscale among Spanish-speaking female sex workers in Mexico. Assessment 29(3):488–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120981768

Etemadi SP, Dehshiri GR (2024) Self-compassion, anxiety, and depression symptoms; the mediation of shame and guilt. Psychol Rep. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941241227525

Ferguson TJ, Eyre HL, Ashbaker M (2000) Unwanted identities: A key variable in shame–anger links and gender differences in shame. Sex Roles: A J Res 42(3-4):133–157. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007061505251

Fischer AH, Manstead ASR (2000) The relation between gender and emotion in different cultures. In Fischer AH (Ed), Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 71–94). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628191.005

Fischer AH, Rodriguez Mosquera PM, van Vianen AE, Manstead AS (2004) Gender and culture differences in emotion. Emotion 4(1):87–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.87

Flach VI, Cariola LA (2025) Developmental trauma and shame-proneness: A systematic review. Trends Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-025-00441-3

Fletcher D, Sarkar M (2013) Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychologist 18(1):12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Freeman KL (2018) The impact of religiosity on shame and self-esteem following a hookup (Master’s thesis). Western Carolina University. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/wcu/f/Freeman2019.pdf

Giannouli V, Giannoulis K (2022) Better understand to better predict subjective well-being among older Greeks in COVID-19 era: Depression, anxiety, attitudes towards eHealth, religiousness, spiritual experience, and cognition. In Worldwide Congress on Genetics, Geriatrics and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research (pp. 359–364). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31986-0_35

Giannoulis K, Giannouli V (2020) Religious beliefs, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression among Greek Orthodox elders. J Anthropol Res Stud 10:84–92. https://doi.org/10.26758/10.1.9

Giannoulis K, Giannouli V (2020) Subjective quality of life, religiousness, and spiritual experience in Greek Orthodox Christians: Data from healthy aging and patients with cardiovascular disease. In GeNeDis 2018: Geriatrics (pp. 85–91). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32637-1_8

Harder DW, Zalma A (1990) Two promising shame and guilt scales: a construct validity comparison. J Personal Assess 55(3–4):729–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674108

Harder DW, Greenwald DF (1999) Further validation of the shame and guilt scales of the Harder Personal Feelings Questionnaire—2. Psychological Rep 85(1):271–281. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.85.5.271-281

Hasui C, Igarashi H, Shikai N, Shono M, Nagata T, Kitamura T (2009) The resilience scale: a duplication study in Japan. Open Fam Stud J 2(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874922400902010015

Kaplánová A, Gregor A (2021) Self-acceptance, shame withdrawal tendencies and resilience as predictors of locus of control of behavior. Psychol Stud 66:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00589-1

Kim S, Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS (2011) Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 137(1):68–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021466

Kim-Prieto C, Diener E (2009) Religion as a source of variation in the experience of positive and negative emotions. J Posit Psychol 4(6):447–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271025

Kitayama S, Markus HR, Matsumoto H, Norasakkunkit V (1997) Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. J Personal Soc Psychol 72(6):1245–1267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1245

Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB (2012) Handbook of religion and health, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press

Lewis M (1971) Shame and guilt in neurosis. International Universities Press

Li CH (2016) Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods 48(3):936–949

Linacre JM (2002) What do infit and outfit, mean-square and standardized mean. Rasch Meas Trans 16(2):878

Long SL (2011) The relationship between religiousness/spirituality and resilience in college students (Doctoral dissertation). Texas Woman’s University

Lucchetti G, Koenig HG, Lucchetti ALG (2021) Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: A review of the current scientific evidence. World J Clin Cases 9(26):7620–7631. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7620

Lutwak N, Ferrari JR (1996) Moral affect and cognitive processes: differentiating shame from guilt among men and women. Personal Individ Diff 21(6):891–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00135-3

Luyten P, Corveleyn J, Fontaine JRJ (1998) The relationship between religiosity and mental health: distinguishing between shame and guilt. Ment Health Relig Cult 1(2):165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674679808406507

McCullough ME, Willoughby BLB (2009) Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol Bull 135(1):69–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014213

McDonald RP, Ho M-HR (2002) Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods 7(1):64–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64

McNeish D (2018) Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here Psychol Methods 23(3):412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG, Lucchetti G (2014) Clinical implications of spirituality to mental health: review of evidence and practical guidelines. Rev brasileira de psiquiatria 36(2):176–182. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1255

Murray K, Ciarrocchi JW (2007) The dark side of religion, spirituality and the moral emotions: shame, guilt, and negative religiosity as markers for life dissatisfaction. J Pastor Couns 42:1–13

Orhan İ, Ünal E, Ağralı C (2025) The relationship between employment guilt and psychological resilience levels of working mothers. Nurs Health Sci 27(2):e70088. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.70088

Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L (1998) Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig 37(4):710–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388152

Pina JAL, Montesinos MDH (2005) Fitting Rasch model using appropriateness measure statistics. Span J Psychol 8(1):100–110

Poole JC, Dobson KS, Pusch D (2017) Anxiety among adults with a history of childhood adversity: psychological resilience moderates the indirect effect of emotion dysregulation. J Affect Disord 217:144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.047

Revelle W, Zinbarg RE (2009) Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika 74(1):145–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9102-z

Rice SM, Kealy D, Treeby MS, Ferlatte O, Oliffe JL, Ogrodniczuk JS (2018) Male guilt–and shame-proneness: the Personal Feelings Questionnaire (PFQ-2 Brief). Arch Psychiatry Psychother 20(2):46–54. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/86488

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(1):1–36

Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Bohus M, Jacob GA, Lieb K (2007) Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 164(3):500–508. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.500

Sawai RP, Noah SM, Krauss SE, Sulaiman M, Sawai JP, Safien AIM (2017) Relationship between religiosity, shame, and guilt among Malaysian Muslim youth. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 7(12):144–155. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i13/3190

Sijtsma K (2009) On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika 74(1):107–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J (2008) The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J. Behav. Med 15(3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Smith BW, Tooley EM, Christopher PJ, Kay VS (2015) Resilience as the ability to bounce back from stress: a neglected concept in resilience research. J Posit Psychol 10(3):247–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.482186

Streiner DL (2003) Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Personal Assess 80(1):99–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18

Tangney JP, Wagner P, Gramzow R (1992) Proneness to shame, proneness to guilt, and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 101(3):469–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.3.469

Tangney JP, Dearing RL (2002) Shame and guilt. Guilford Press

Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Hafez L (2011) Shame, guilt, and remorse: Implications for offender populations. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 22(5):706–723

Tracy JL, Robins RW (2006) Appraisal Antecedents of Shame and Guilt: Support for a Theoretical Model. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 32(10):1339–1351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206290212

Van Cappellen P, Toth-Gauthier M, Saroglou V, Fredrickson BL (2016) Religion and well-being: the mediating role of positive emotions. J Happiness Stud 17:485–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9605-5

Van Vliet KJ (2008) Shame and resilience in adulthood: a grounded theory study. J Couns Psychol 55(2):233–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.233

Varghese ME (2015) Attachment to God and psychological well-being: shame, guilt, and self-compassion as mediators. Purdue University. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/578

Vigfusdottir J, Høidal R, Breivik E, Jonsbu E, Dale KY, Mork E (2024) The Norwegian version of the Personal Feelings Questionnaire-2: clinical utility and psychometric properties. Curr Psychol 43:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-07101-2

Vishkin A, Bigman Y, Tamir M (2014) Religion, emotion regulation, and well-being. In Religion and spirituality across cultures (pp. 247–269). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_13

Ward SJ, King LA (2018) Moral self-regulation, moral identity, and religiosity. J Personal Soc Psychol 115(3):495–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000207

Wright BD, Masters G (1997) The partial credit model. Handbook of modern item response theory, 101–121

Yıldız S, Yüksel MY (2024) The mediator role of depression, stress, and anxiety in the relationship between childhood trauma experiences and psychological vulnerability. Int J Psychol Educ Stud 11(3):247–257. https://doi.org/10.52380/ijpes.2024.11.3.1330

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the participants of this study for sharing their personal experiences, making this research possible. We also extend our appreciation to the Ethics Committee of Psychological and Educational Research for their support in participant recruitment. This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: conceptualization, project administration, investigation, methodology, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review & editing, validation, formal analysis, data curation. RMA: conceptualization, data curation, writing-review & editing. DSAA: visualization, validation. SAAD: formal analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Psychological and Educational Research in Libya (reference number: MMST/2/1/25M) on July 15, 2024.

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the aims and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained online between July 28 and October 20, 2024, prior to participation. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality of their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, M., Mohamed Abdelrahman, R., Alyousef, D.S.A. et al. Shame and guilt in Arab populations: validation of PFQ-2 and the mediating role of psychological distress. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1581 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05864-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05864-y