Abstract

We assess the relative contributions of land, atmosphere, and oceanic initializations to the forecast skill of root zone soil moisture (SM) utilizing the Community Earth System Model version 2 Sub to Seasonal climate forecast experiments (CESM2-S2S). Using eight sensitivity experiments, we disentangle the individual impacts of these three components and their interactions on the forecast skill for the contiguous United States. The CESM2-S2S experiment, in which land states are initialized while atmosphere and ocean remain in their climatological states, contributes 91 ± 3% of the total sub-seasonal forecast skill across varying soil moisture conditions during summer and winter. Most SM predictability stems from the soil moisture memory effect. Additionally, land-atmosphere coupling contributes 50% of the land-driven soil moisture predictability. A comparative analysis of the CESM2-S2S SM forecast skills against two other climate models highlights the potential for enhancing soil moisture forecast accuracy by improving the representation of soil moisture-precipitation feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

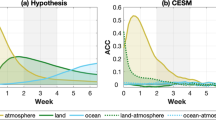

The Subseasonal-to-Seasonal (S2S) forecast spans from two weeks to six weeks, bridging the gap between short-range weather forecasts and long-range seasonal outlooks. S2S forecasts offer a broad spectrum of potential applications, encompassing public health, disaster preparedness, water management, energy, and agriculture1. Nonetheless, significant challenges persist, particularly as the S2S forecast accuracy declines noticeably in initial condition-based numerical weather prediction systems2 and their Artificial Intelligence (AI) counterparts3. Forecast accuracy, attributed to high-fidelity process representation, is hypothesized to emerge at S2S time scales (Fig. 1). For example, coupled ocean-atmosphere variability modes, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, the Madden-Julian Oscillation, and tropical-extratropical teleconnections, are recognized as sources of S2S predictability4,5,6. Additionally, persistent circulation anomalies in the stratosphere and their dynamic linkages to the troposphere during the winter season7 and land surface memory and its interactions with the atmosphere contribute to further S2S predictability8,9.

This framework, motivated by Mariotti et al.2, highlights the influence of climate processes, including atmospheric, land, and ocean processes and their interactions, on improving sub-seasonal forecast skills for root-zone soil moisture predictions. Importantly, this framework underscores the critical role of land surface initialization in developing skillful soil moisture forecasts.

Water-related S2S forecasts pose unique challenges, with the precipitation forecast skill quantified by the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) falling below 0.1 in the mid-latitude regions10. We posit that an Earth System Predictability (ESP) framework (Fig. 1), characterized by a skillful prediction (ACC > 0.5) in the land component, can benefit food and water sectors11,12,13. The land surface integrates less predictable precipitation signals with soil moisture memory and the soil-plant-atmosphere interaction processes, resulting in a more predictable soil moisture signal critical for agricultural and water planning12,14,15. Soil moisture variability is significantly correlated with water availability in the Southwestern US16, including the Colorado River basin17. Soil moisture observations serve as the reference data to assess the performance of various drought indices for crop yield monitoring18,19. Henceforth, we refer to root zone soil moisture integrated from the surface to a 0.5-meter depth, focusing mainly on agricultural applications20. We examined the relative contributions of the ocean, land, and atmosphere components and their interactions to S2S soil moisture forecasting through an extensive set of eight sensitivity experiments (see Method)10. We determined that land initializations and soil moisture memory processes primarily influence soil moisture predictability (demonstrated subsequently).

Soil moisture, a key component of land processes, exhibits slower variability than atmospheric conditions and is recognized as a source of predictability for S2S forecasting9,21,22. Soil moisture is more predictable12,23 due to its memory effects14 and feedback to the meteorological drivers, e.g., temperature and precipitation9,22. Standalone land-only or hydrology sensitivity studies have emphasized the importance of initial conditions and climate forcing in improving hydrological forecasts24,25. However, the limited skill improvement in the coupled forecasting system10,22 poses a challenge in assessing the effects of land surface initializations. Given its importance for the agriculture and water sectors, we demonstrate that soil moisture forecast is a robust metric, providing a pathway to process-level investigation in improving water-related S2S forecasting.

Results

Sub-seasonal soil moisture forecast skill attributed to land initializations

We employed the Community Earth System Model version 2 sub-seasonal prediction system (CESM2-S2S) to evaluate the skill of soil moisture forecasts26,27 (see Method). Land initialization significantly improves the skill of week 3–4 soil moisture forecasts, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1. In single-component initialization experiments, land consistently yields the most significant contribution to the forecast skill, followed by the atmosphere (Fig. 2b–m). Across all four seasons, the forecast skill from land-only initialization is twice as high (ACC = 0.38) as from atmosphere-only initialization (ACC = 0.20). In the most agriculturally intensive region, the Prairie Peninsula (NEON #6), the ACC for land-only initialization is three times higher (ACC = 0.39) than atmosphere-only initialization (ACC = 0.13). Ocean-only initializations contribute minimally to week 3–4 soil moisture forecast.

The top panel (a) shows agricultural intensity in the contiguous US. The bottom panels (b–m) display the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) between one-component-only initialized forecasts and observations for root zone soil moisture anomalies. The three columns represent sensitivity experiments with initializations from atmosphere-only (ATM), ocean-only (OCN), and land-only (LAND). The four rows correspond to the four seasons: MAM, JJA, SON, and DJF. The correlations are calculated over 300 weeks from 1999 to 2018. For ATM, JJA, and SON, data are available from 1999 to 2010. Stippling indicates that the ACC is significant at the 95% confidence level based on a t-test with degrees of freedom calculated at each point.

A low ACC for atmosphere-only (ATM) and ocean-only (OCN) initializations can be attributed to the absence of soil moisture memory effects, which are critical for soil moisture predictability12,14. Soil moisture memory, which arises from the slow dynamics of soil water retention and decay, plays a significant role in influencing predictability when the land component is properly initialized (LND). However, when the land is not initialized, such as when land climatology (anomaly = 0) is used, the memory-driven ‘anomaly persistence’ cannot contribute to predictability, as demonstrated in the ATM and OCN initialization cases.

Land initialization synergistically enhances sub-seasonal forecast skill, particularly in the interior of the US (NEON #6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), where agricultural activity is prominent and predictability from atmospheric and oceanic sources is limited. For example, in the Northern Plains (NEON #9), land is the sole source of predictability (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Conversely, atmospheric contributions, and to a lesser extent ocean contributions to the forecast skill, are more pronounced in coastal ecoclimatic regions such as the southeast, southern plains, and southwest (NEON #2, 3, 4, 11, 14, 15, and 17; Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Next, we investigated forecast skill variations with lead time, averaging across all four seasons.

Throughout all forecast lead times and four seasons, the land remains the primary source of predictability (Fig. 3). However, as expected, forecast skill decreased from week 1–2 (ACC = 0.54) to week 5–6 forecasts (ACC = 0.37) in the standard forecast where all three components are initialized. Removing atmosphere initialization results in a skill drop of 5% or less, with the ACC decreasing from 0.43 in the standard forecast to 0.39 in the climoATM experiment for week 3–4 forecasts (3rd column in Fig. 3). Furthermore, eliminating ocean initialization minimally impacts forecast skill, with a 1% decrease observed in the longer lead, i.e., 5–6 weeks forecasts (2nd column in Fig. 3). However, removing land initialization dropped the forecast skill almost 50% across all forecast lead times, e.g., ACC decreased to 0.23 in the climoLND experiment for week 3–4 forecasts (Fig. 3h).

The three rows display the anomaly correlation coefficients (ACC) of root zone soil moisture forecasts for weeks 1–2 (a–d), 3–4 (e–h), and 5–6 (panels i–l), compared with corresponding observations. The forecast skills in the standard experiment incorporate initializations from all three components: Atmosphere (ATM), Ocean (OCN), and Land (LND). Additionally, three sensitivity experiments are shown: LND + ATM (climoOCN), LND + OCN (climoATM), and ATM + OCN (climoLND). ACC is computed over 1200 weeks spanning 1999 to 2018, with stippling indicating significance at the 95% confidence level based on a t-test with degrees of freedom calculated at each point.

Predictability sources and their regional and seasonal variations

During summer (JJA), the peak growing season, land contributions to the total forecast skill are maximized. Specifically, land accounts for 93 ± 3% of the total root zone soil moisture forecast skill, as observed in the control experiment averaged across 17 NEON ecoclimatic regions covering the contiguous US (Fig. 4, and Table 1 and S1, top panels). Hereafter, X ± Y represents the mean, with two times the standard error estimates calculated across the 17 NEON ecoclimatic regions. A significant portion of atmospheric contributions (45 ± 10%) is attributed to land-atmosphere coupling (42 ± 8%), which is already accounted for within the land contribution (compare yellow dashed line with red solid line in Fig. 4). Consequently, the addition or removal of atmospheric initialization does not substantially affect soil moisture forecast skill (Fig. 4).

Figure panels present the root zone soil moisture forecast Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) with observations as a function of forecast lead time. The upper panels represent JJA, and the bottom panels represent DJF. Contributions from land-atmosphere coupling (yellow dash), ocean-atmosphere coupling (violet dash), land-ocean coupling (cyan dash), and the sum of all components (grey dash) are derived from reforecast experiment calculations (see Method). Green, violet-red, and cyan shadings show contributions from Land, Atmosphere, and Ocean sources, respectively. The various panels depict the seventeen NEON ecoclimatic regions in the contiguous US, organized sequentially by NEON region boundaries (see inset figure).

A linear combination of three predictability sources – land, atmosphere, and ocean – and their couplings mainly explains the total predictability observed in the control experiment (compare the sum line with the standard forecast line in Fig. 4, see Method). The summation of individual predictability components can elucidate 94 ± 8% of total predictability in the JJA season. A more considerable uncertainty ( ~ 25%) is observed in the central US region, such as NEON #6 and #9, where oceanic sources negatively contribute to total predictability (Table 1, top panel), likely due to significant dry biases in the CESM2’s precipitation forecast28, thereby resulting in the summation line appearing greater (by 25%) than the standard forecast (see Method). Additionally, we found land-atmosphere coupling as the uncertainty source in the Pacific Southwest (NEON # 17) and northern Rockies (NEON # 12), where atmosphere-only initialization shows a smaller skill than land-atmosphere coupling effects; thus, the sum of predictability components is 20–25% smaller than the standard forecast (see Method).

Land remains the primary source of soil moisture predictability even during winter, where its contribution (88 ± 6%) is slightly less than that in summer (93 ± 3%). Additionally, the contribution of the land-atmosphere coupling (28 ± 7%) is smaller than that of the atmosphere (39 ± 10%). Furthermore, oceanic contributions become more prominent with longer lead times, particularly in the coastal ecoclimatic regions. For instance, oceanic contributions to total predictability are 58%, 51%, and 32% in the Atlantic Neotropical (NEON #4), Southern Plains (NEON #11), and the Southeast (NEON #3), respectively. Most oceanic contributions came through the land-ocean coupling process in the Southeast and Atlantic Neotropical regions (compare cyan dashed lines with blue solid lines for NEON # 3 and 4 in Fig. 4). Therefore, in the Southeast region, total predictability only marginally improved (10-15%) compared to land-only predictions.

Predictability of hydroclimatic extremes

The predictability of hydroclimatic extremes (i.e., droughts and pluvial events) is generally lower than that of all soil moisture conditions. To increase the sample size, we defined drought conditions as instances where observed standardized soil moisture anomalies are less than −0.5, which accounts for 30% of all forecasts. This definition represents drought events aggregated over a two-week timescale using a standardized soil moisture anomaly metric29 (see Method). Averaged across the contiguous US during the JJA season, the correlation coefficient (ACC) between drought forecasts and observations is 0.22 (Fig. 5d), compared to an ACC of 0.42 for all soil moisture variability conditions (Supplementary Fig. S1). Notably, land initializations predominantly contribute to drought predictability (89 ± 5%), with nearly all predictable components originating from land sources during the summer (97 ± 10%) (see Fig. 5d, f). Conversely, the combined influence of atmospheric and oceanic initializations peaks in the spring season. Given that most oceanic and atmospheric effects manifest through interactions with the land (Fig. 4), the standard forecast skill improved marginally compared to the land-only initialization experiment (compare the first and third columns in Fig. 5).

Panels show the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) between forecast experiments and observations for standardized soil moisture anomalies. Panels (a–l) represent dry conditions (anomalies < −0.5), and panels (m–x) represent wet conditions (anomalies > 0.5). The three columns correspond to the standard forecast (ATM + OCN + LAND) and two sensitivity experiments (ATM + OCN and LAND only), primarily contributing to forecast skill. The four rows represent the four seasons: MAM, JJA, SON, and DJF. The correlation is calculated over 300 weeks from 1999 to 2018. Stippling indicates statistical significance at the 95% confidence level, based on a t-test with degrees of freedom calculated at each point.

Drought forecast skills are notably higher across critical agricultural regions in the contiguous US, especially during the growing season (spring and summer). For example, the Prairie Peninsula (NEON # 6) demonstrates an ACC of 0.42 in spring (March-May) (Fig. 5; top panels). Similarly, the Appalachian and Cumberland Plateau (NEON # 7) and the Ozark Complex (NEON # 8) exhibit ACC values of 0.36 and 0.34, respectively, during summer (June-August). Enhanced drought prediction capabilities offer substantial potential benefits for agricultural applications, addressing significant challenges previously noted in forecasting drought onset, such as the 2012 drought in the Great Plains30.

Wet extremes (pluvial), defined as standardized soil moisture anomalies greater than 0.5, exhibit slightly lower predictability compared to dry extremes, particularly during the growing season (see top and bottom panels in Fig. 5). Seasonally, the fall (September-November) shows the highest forecast skills for wet extremes, with an ACC of 0.25 ± 0.04, primarily due to land contributions (76 ± 8%). On average, across all seasons, atmospheric and oceanic sources collectively contribute more to the predictability of wet extremes (59 ± 15%) than dry extremes (42 ± 10%).

Role of climate processes

The soil moisture memory process significantly contributes to sub-seasonal soil moisture predictability from land sources (Supplementary Fig. S2). The memory process characterizes the decay rate of soil water within the root zone, influenced by coupled climate-vegetation-hydrological processes14,16,31. We conducted lead-lag auto-correlation analysis of daily soil moisture anomalies using the Community Land Model version 5 (CLM5) offline, which serves as the land model within the sub-seasonal prediction system (see Method). The auto-correlation analysis revealed that the 21-day lag autocorrelation closely aligns with the 3–4 week soil moisture forecast skill in the land-only initialized experiment (climoATMclimoOCN). Given the limited precipitation forecast skill (ACC < 0.1) at sub-seasonal time scales10, this finding can be expected.

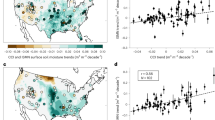

The soil moisture to precipitation feedback loop enhances sub-seasonal forecast skill (Fig. 6). We compared the CESM2-based soil moisture forecast skill with two other sub-seasonal experiments32 – RSMAS-CCSM433 and ESRL-FIM34, both of which provide vertically integrated full depth (FD) soil moisture forecasts in their standard configurations. Additionally, we compared CESM2 full depth forecast skill, keeping the reference data the same as in the previous analysis. The ESRL-FIM model consistently outperforms CESM2 by 7%, which, in turn, shows improved performance compared to its predecessor version (CCSM4) (Fig. 6a). For instance, week 3 to 4 forecast skills are 0.49, 0.43, and 0.36 for ESRL-FIM, CESM2, and RSMAS-CCSM4 in the contiguous US. Full-depth soil moisture exhibits reduced variability and extended memory compared to the root zone14. Consequently, the full-depth forecast demonstrates lower skill than the root zone forecast for weeks 1 to 3, but higher skill for weeks 3 to 6 in the CESM2 forecast.

FD Full Depth, and RZ Root Zone. a Forecast skill of soil moisture anomalies in the three S2S models, represented by the area-weighted average ACC across the continental US for all seasons. The ESRL-FIM forecast is limited to 32 lead days. Data are smoothed using a 14-day running mean, resulting in an effective verification lead time of 7 to 25 days for ESRL-FIM and 7 to 39 days for the other models with 46-day lead forecasts. b–e Correlation between soil moisture initial state and week 3–4 precipitation forecast during spring (MAM) and summer (JJA) seasons. Stippling indicates statistically significant correlations at the 95% confidence level.

The soil moisture to precipitation feedback loop was investigated by correlating initial soil moisture anomalies (FD) with the week 3–4 precipitation forecast in the two highest-performing models: ESRL-FIM and CESM2. The ESRL-FIM model demonstrates considerably stronger soil moisture to precipitation feedback in the central US, particularly during the summer season (Fig. 6e). For instance, the ESRL-FIM model shows that the week 3–4 precipitation forecast is significantly correlated with the initial soil moisture anomalies in most of the central US, with a contiguous US average ACC value of 0.14 and the highest ACC greater than 0.4 found in parts of the Northern Plains (NEON # 9). The soil moisture-precipitation feedback loop is largely missing in the CESM2-S2S precipitation forecast, particularly in the summer, with an average ACC value of −0.03 across the contiguous US (Fig. 6d). The CESM2-S2S forecast shows statistically significant feedback in parts of the Southeastern US during the spring season (Fig. 6b). The root zone soil moisture anomalies exhibit slightly weaker feedback on the week 3-4 precipitation forecast in the CESM2 model (Supplementary Fig. S3) compared to the full depth to precipitation feedback presented in Fig. 6.

Discussion

On a sub-seasonal time scale, atmospheric initializations contribute most to the forecast skill for near-surface air temperature predictability. Experiments with single-component initializations reveal that the forecast skill for atmosphere-only initialization (ACC = 0.26) is nearly twice that of land-only (ACC = 0.14) and ocean-only (ACC = 0.13) initializations, averaged across all four seasons and the contiguous US (Supplementary Fig. S4). The skill in precipitation forecasting is limited and primarily attributed to atmospheric initialization (ACC = 0.09) (Supplementary Fig. S5). These findings, discussed in our previous study10, provide context for the new results presented here.

This study demonstrates that accurate initialization of land conditions can significantly enhance sub-seasonal forecast skills for land-related quantities, such as root zone soil moisture, which is critically important for agriculture and water planning. We utilized an ensemble of four observationally constrained soil moisture datasets - ERA5-land, SMERGE, GLEAM3, and MERRA2 - for model verification, which reduces the sensitivity of our results to the selection of any single observational dataset35,36 (see Method). The land initialization method used in this study, derived from offline land model simulations (see Method), is relatively simple. Advances in soil moisture observational networks37,38, remote sensing technology39, and data assimilation methods40,41 are expected to improve forecast skills further.

A smaller subset of Data Assimilation (DA) experiments conducted from 2011 to 2019 shows a minor improvement (< 5%) in soil moisture forecasting skills for the contiguous US (Supplementary Fig. S6). The DA experiment utilized observationally constrained atmospheric initial conditions and the associated land surface states, as described by Raeder et al.42. It is important to note that soil moisture observations were not directly assimilated in the DA experiment; instead, the land states were indirectly influenced by the atmospheric drivers from the Community Atmospheric Model version 6 (CAM6), which assimilated a wide range of global observations, including aircraft, radiosonde, infrared, and radio occultation data42. Hence, a minor improvement in soil moisture forecasting skills can be expected. Future research should explore more advanced DA methodologies, such as four-dimensional ensemble variational (4D-EnVar)-based weakly coupled land data assimilation43 and ocean data assimilation strategies17,44. Moreover, advances in ocean-atmosphere coupling and its teleconnections to land surface processes could further enhance soil moisture predictability45,46.

The regional variations in soil moisture predictability are influenced by biases in the climate model’s representation of land-atmosphere and ocean-atmosphere coupling, which vary significantly across different ecoclimatic regions. For example, in the central US (e.g., NEON #6 and #9), dry precipitation biases in the CESM2 model28 led to an overestimation of contributions from oceanic sources, thereby diminishing forecast accuracy. Addressing these biases requires improvements in the representation of large-scale circulation patterns (e.g., Rossby waves)47, thermodynamic processes including land-atmosphere coupling, atmospheric parameterizations48, and high-resolution climate modeling28. Additionally, enhancing the coupling of convection to the larger-scale environment may further reduce summertime precipitation biases over the central U.S.49.

Some of our findings, such as the low precipitation forecasting skill (Supplementary Fig. S5) and weaker land-atmosphere feedback (Fig. 6) are CESM2 model dependent10,27. Their implications for soil moisture forecasting warrant further investigation. The availability of new soil moisture forecasting datasets, such as those from the Canadian Seasonal to Inter-annual Prediction System version 2.150, and the Norwegian Climate Prediction Model (NorCPM) soil moisture data assimilation system51, provide an opportunity to conduct a comprehensive multi-model comparison study. To strengthen the robustness of these comparisons, additional sensitivity experiments, e.g., as outlined in Table 1, are recommended.

It is important to note that the standardized soil moisture index used in this study primarily identifies soil moisture drought, which is closely related but differs from meteorological and hydrological droughts. While meteorological droughts are driven by precipitation deficits and related atmospheric circulation anomalies30, and hydrological droughts manifest as reductions in streamflow and groundwater levels, soil moisture drought is more directly associated with root-zone water availability and land-atmosphere interactions52. It serves as a critical link between meteorological and hydrological droughts by translating precipitation deficits into surface and subsurface water stress53, influencing evapotranspiration and ecosystem responses54. Overall, our results focus on soil moisture anomalies rather than a comprehensive assessment of all drought types55,56.

Pluvial conditions, defined based on wet soil moisture anomalies, align with hydrometeorological studies57,58 but do not inherently reflect hydrological flood events. A high soil moisture level indicates saturated conditions conducive to flooding59. However, soil moisture alone does not fully define hydrological floods, as their occurrence involves complex hydrological and geomorphological processes, including antecedent moisture, topography, and drainage capacity60,61. Our approach captures extreme soil wetness conditions relevant to land-atmosphere interactions58 rather than a comprehensive hydrological flood classification.

Causality and predictability are distinct aspects of climate variability. While phenomena such as flash droughts can originate from large-scale atmospheric conditions, they are often not predictable in sub-seasonal prediction systems. For instance, Hoerling et al.28 identified that the 2012 flash drought in the Great Plains was caused by reduced atmospheric moisture transport from the Gulf of Mexico, yet the seasonal prediction system did not predict this event. Our study demonstrates that land conditions provide a crucial predictability component that can enhance the skill of forecasting high-impact weather and climate events. Additionally, recent advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) methodologies demonstrate the potential to enhance the predictive accuracy of hydroclimatic extremes62.

This study contributes to the growing body of literature highlighting the critical role of land surface processes in improving S2S forecasting while providing novel insights. Our work diverges from the studies of Lim et al.63 and Nair et al.51 in terms of focus, methodology, and key findings. Lim et al.63 focus on temperature predictability by employing land-atmosphere coupling metrics within a standard forecast framework, whereas our study investigates soil moisture predictability through a novel set of sensitivity experiments designed to isolate the impact of land surface initializations (Table 1). On the other hand, Nair et al.51 examine the influence of soil moisture data assimilation using the Norwegian Climate Prediction Model (NorCPM) and demonstrate improvements in S2S forecasts driven by observational constraints. In contrast, our study leverages CESM2-S2S and systematically disentangles the relative contributions of land, atmosphere, and ocean initializations to sub-seasonal soil moisture forecasts. Notably, we find that land initializations account for 91 ± 3% of the forecast skill for soil moisture, underscoring their importance. While these studies represent complementary approaches to advancing S2S forecasting, our findings uniquely establish the dominant role of land surface initializations in enhancing soil moisture predictability, with direct implications for agricultural and water resource applications.

Methods

Sub-seasonal Prediction System

The CESM2 sub-seasonal prediction system (CESM2-S2S) consists of a fully coupled CESM2 retrospective forecast at 1° nominal resolution, initialized every Monday from 1999 to 202027. Each weekly reforecast is integrated over a 45-day lead time with an 11-member ensemble size. Since April 2021, a real-time forecast with a 21-member ensemble size has been generated and contributes to the multi-model sub-seasonal prediction experiment dataset32. The atmospheric component is initialized using the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Climate Forecast System version 2 (CFSv2) reanalysis64. The land component is initialized using standalone Community Land Model version 5 (CLM5) simulations driven by CFSv2 reanalysis climate forcing65. The initializations for ocean and sea-ice conditions are obtained from a standalone CESM2 ocean simulation forced with the adjusted Japanese 55-year reanalysis state field and fluxes66. The CESM2-S2S system demonstrates temperature and precipitation skills at par with the NCEP CFSv2, slightly lower than the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) system27. CESM2 is a community model that enabled us to conduct additional sensitivity experiments involving university researchers and students.

The Community Land Model version 5 (CLM5)65 is the land component in CESM2. CLM5 represents a range of biophysical and biogeochemical processes, including land surface heterogeneity, radiation scheme, momentum, energy balance, hydrology, photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, carbon and nutrient cycling, land-use change, crops, irrigation, and fertilization65,67. Each CLM5 1° × 1° grid cell consists of multiple soil columns, each with a vertically resolved soil profile discretized into up to 20 hydrologically active layers with spatially varying total thickness68. CLM5 incorporates a prognostic seasonal cycle for vegetation evolution, encompassing leaf emergence, senescence, and vegetation height dynamics69,70. Landscape heterogeneity is represented through a plant functional type tile structure, including rainfed and irrigated agricultural practices65,67.

Experiment design

The unique set of eight experiments outlined in Table 2 enables us to discern the individual contributions of the atmosphere (ATM), land (LND), and ocean (OCN), as well as their interactions, to the forecast skill of soil moisture. These experiments further allow us to deconstruct the sources of predictability into those arising from anomalies (A), couplings (C), and the climatological state (climo) of each component. The first experiment is a control wherein all three components are initialized, as in the standard sub-seasonal prediction system27. After this, seven additional experiments are conducted, wherein one or more components are maintained at their climatological state, ensuring that the anomaly of the selected component does not contribute to the forecast skill10.

The coupling between two components is active if either both or one component is initialized to its anomalous state. For instance, land-atmosphere coupling (LNDATM_C) is considered the same as that of the control and climoATM experiments (Table 2). The underlying assumption is that when one component, such as LND in the climoATM experiment, is initialized using its anomalous state, it exerts stronger coupling to align the climatologically initialized component (ATM) with the land anomalous state at the surface. However, if both components are initialized to their climatological state, the coupling is set to zero, e.g., the land-atmosphere coupling is zero in the climoATMclimoLND experiment. We verify this assumption by comparing the control experiment’s forecast skill with the skill’s algebraic sum from individual sources (Fig. 4).

The summary of CESM2-S2S reforecast experiments is listed in Eq. 1 to Eq. 8. The CESM2-S2S eight experiments (bold term) are the direct output from the reforecast with eight Initial Conditions (ICs) settings. In the Equation, the Clim is climatology, A is anomaly ICs, and the C is the coupling term. The eight settings follow the same reforecast protocol, with specific climatological ICs as listed in the left-hand set of the equations, i.e., the name of the reforecast set. The right-hand set of the Equation consists of the components that contributed to the ACC. The assumption is that average couplings in different experiment sets do not change considerably. For example, the land-atmosphere coupling is supposed to be of the same value in Eqs. 2 and 3, but the difference contributes to part of the biases between the model control run and the sum of individual parts in Eq. 15. Another assumption is that two model components are set to climatological ICs; their coupling is close to zero—no coupling term in Eq. 8.

The total predictabilities include predictability from the background climatology (ClimALL), anomalies of each component (AATM, ALND, AOCN), and their coupling (CLNDATM, COCNATM, CLNDOCN) reflected in the standard forecast (Eq. 1). In Eqs. (2)-(4) are reforecast experiments where one of the modeling components (ATM, LND, OCN) is kept at its climatological state. In Eqs. 5 to 7, two of the modeling components are kept at their climatological states. All modeling components are kept at their climatological states in experiment 8 (climoALL).

Experiments 5 to 7 have been used to determine predictability from one source only as follows:

Here, P is the predictability contributed from the individual sources. In this study, we use the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) between observation and forecasted anomalies as the metric to assess the predictability. Predictability from the coupling terms is derived from the linear combination of four experiments, as shown below.

All predictability sources are summarized in Eq. 15 and compared with the predictability in the standard forecast to assess the validity of the linear assumption.

Verification datasets

We utilized an ensemble mean of four soil moisture products based on reanalysis and remote sensing: ERA5-Land71, SoilMerge36, the Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model (GLEAM)72, and the Modern Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications version 2 (MERRA2)73. The root zone soil moisture is vertically integrated from the surface to 0.5 m depth. ERA-5 land soil moisture is a reanalysis dataset based on numerical integrations of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) land surface model71. The core land model is the Carbon Hydrology-Tiled ECMWF Scheme for Surface Exchanges over Land (CHTESSEL). SoilMERGE (SMERGE) is a new root-zone soil moisture that covered the continental US with 0.125° resolution from 1979-2018. All model-observation correlations were truncated in 2018 due to the SMERGE. SMERGE root zone soil moisture is based on merging the North American Land Data Assimilation System (NLDAS) and satellite retrievals from the European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (ESA-CCI)36. The Global Land Evaporation Amsterdam Model (GLEAM) SM is a satellite-based root-zone SM from different passive and active C- and L-band microwave sensors, Ocean Salinity (SMOS) satellite in the v3c data set (European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative, ESA CCI) with 0.25° resolution72,74. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA2) is a reanalysis dataset generated by rerunning a revised version of the land component of the MERRA2 system75. The latitude and longitude resolutions are 0.5 and 0.625°. All four observations are re-gridded to CESM2 (1° × 1°) resolution using the Earth System Modeling Framework area weighted Method.

The skill of soil moisture forecasts varied across the verification datasets, with MERRA2 demonstrating the highest skill and ERA5-Land exhibiting the lowest (Supplementary Fig. S7). Therefore, employing the ensemble mean of these four observation-based products reduces uncertainty in observational data while accounting for regional variations in land use, climate, and topography35. The ensemble mean approach outperforms any individual dataset as well as combinations of three datasets (SMERGE, GLEAM MEARR2). For example, the soil moisture forecast skill for weeks 3–4 (16–30 days) in the control experiment, using the ensemble mean as the observation, is 0.43 (Fig. 3e). In comparison, the forecast skill using individual datasets is 0.24 for ERA5-Land (Figure. S8e), 0.32 for SMERGE (Figure. S9e), 0.40 for GLEAM (Figure. S10e), and 0.42 for MERRA2 (Figure. S11e). Additionally, the combination of three datasets yields a forecast skill of 0.42 (Figure. S12e), which remains lower than the ensemble mean.

Furthermore, Quadruple Collocation Analysis (QCA), an extension of the Triple Collocation Method to four datasets76, resulted in inconclusive results including negative error variance for ERA5-Land (Supplementary Fig. S13). This issue arises because several datasets share common input sources, such as ESA-CCI remote sensing-based soil moisture observations in SMERGE and GLEAM, and atmospheric reanalysis-based meteorological forcing used to drive the underlying land surface models. For example, SMERGE assigns 80% weightage to the underlying land surface model data in forested regions36, further reducing the independence of error sources. As a result, the assumption of independent errors in QCA does not fully hold, particularly in data-rich regions like the U.S., where overlapping data assimilation can introduce dependencies, potentially biasing error variance estimates and reducing the reliability of QCA results.

Additionally, we employed the National Ecological Observatory Network’s (NEON) ecoclimatic domains to assess regional variations in forecast skill within the US. The NEON ecoclimatic domains (Fig. 2a) delineate distinct regions based on climate, topography, soil type, and vegetation dynamics77.

Standardized anomalies

We reorganized the forecast data into seven dimensions: latitude (25) × longitude (46) × lead time (46) × week (5) × month (12) × year (23) × ensemble (11). The CESM2 grid covers the contiguous US with 25 latitudes and 46 longitudes. In the Equation, i and j represent latitude and longitude, respectively. The variables l, w, m, and y denote forecast lead days (46), initial weeks (5), initial months (12), and initial years (1999 to 2021), while e represents ensemble members.

First, we computed the ensemble mean forecast by averaging the forecast across the 11 ensemble members. Next, we applied a 14-day running mean along the forecast lead dimension to reduce high-frequency daily variability, resulting in usable data for lead days 7 to 39. We then computed standardized anomalies along the year dimension. This Method removes the re-forecast climatology as a function of forecast lead time and initialization time, thereby minimizing the effects of forecast initialization shock and drifts in the sub-seasonal prediction system78.

We rearranged the observation data in the same manner as the forecast and computed the observation standardized anomalies. For the ACC calculation, the forecast dimensions were transformed into latitude, longitude, lead time, and week. The week dimension totals 1200 (20 years [1999 to 2018] × 12 months × 5 weeks) for the all-year ACC calculation (e.g., Fig. 3). For seasonal correlation (Fig. 2), the week dimension was concatenated into four seasons, totaling 300 weeks (20 years × 3 months × 5 weeks). Since most months have only four weeks, the fifth-week data is considered missing, i.e., out of 1200 weeks, only 20 × 52 = 1040 weeks have the data, and the remaining 160 weeks are missing.

Evaluation metric

We calculated the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC) between the forecast and observation anomalies to assess the soil moisture forecast skill. The forecast anomaly is calculated relative to lead time and initialization time-dependent forecast climatology that minimizes the impact of initialization drift on the forecast12,78. We applied a 14-day running mean to smooth the daily variations; hence, the valid lead days for verification are 7 to 39 days.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly accessible and can be found in the cited references. All CESM2 forecast sets are accessible through the NSF NCAR Climate Data Gateway at https://doi.org/10.5065/0s63-m767. The ERA5 Reanalysis data is freely available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e2161bac. GLEAM Soil Moisture data can be accessed at https://www.gleam.eu/. SoilMerge data can be downloaded using https://doi.org/10.5067/PAVQY1KHTMUT. MERRA-2 data is available via https://doi.org/10.5067/VJAFPLI1CSIV.

Code availability

The analysis scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14036205.

References

White, C. J. et al. Potential applications of subseasonal‐to‐seasonal (S2S) predictions. Meteorological Appl. 24, 315–325 (2017).

Mariotti, A., Ruti, P. M. & Rixen, M. Progress in subseasonal to seasonal prediction through a joint weather and climate community effort. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 4 (2018).

Bi, K. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533–538 (2023).

DelSole, T., Trenary, L., Tippett, M. K. & Pegion, K. Predictability of week-3–4 average temperature and precipitation over the contiguous United States. J. Clim. 30, 3499–3512 (2017).

Mariotti, A. et al. Windows of opportunity for skillful forecasts subseasonal to seasonal and beyond. B Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E608–E625 (2020).

Zhou, S., L’Heureux, M., Weaver, S. & Kumar, A. A composite study of the MJO influence on the surface air temperature and precipitation over the continental United States. Clim. Dynam 38, 1459–1471 (2012).

Kidston, J. et al. Stratospheric influence on tropospheric jet streams, storm tracks and surface weather. Nat. Geosci. 8, 433–440 (2015).

DeAngelis, A. M. et al. Prediction skill of the 2012 US Great Plains flash drought in subseasonal experiment (S2S) models. J. Clim. 33, 6229–6253 (2020).

Koster, R. D. Contribution of land surface initialization to subseasonal forecast skill: First results from a multi-model experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 1–6 (2010).

Richter, J. H. et al. Quantifying sources of subseasonal prediction skill in CESM2. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 59 (2024).

Duan, Y. & Kumar, S. Predictability of Seasonal Streamflow and Soil Moisture in National Water Model and a Humid Alabama–Coosa–Tallapoosa River Basin. J. Hydrometeorol. 21, 1447–1467 (2020).

Esit, M. et al. Seasonal to multi-year soil moisture drought forecasting. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 16 (2021).

Koster, R. D., Liu, Q., Crow, W. T. & Reichle, R. H. Late-fall satellite-based soil moisture observations show clear connections to subsequent spring streamflow. Nat. Commun. 14, 3545 (2023).

Kumar, S., Newman, M., Wang, Y. & Livneh, B. Potential reemergence of seasonal soil moisture anomalies in North America. J. Clim. 32, 2707–2734 (2019).

Goldsmith, G. R. Changing directions: the atmosphere-plant-soil continuum. N. Phytol. 199, 4–6 (2013).

Kumar, S., Dewes, C. F., Newman, M. & Duan, Y. Robust changes in North America’s hydroclimate variability and predictability. Earth’s. Future 11, e2022EF003239 (2023).

Chikamoto, Y., Wang, S.-Y. S., Yost, M., Yocom, L. & Gillies, R. R. Colorado River water supply is predictable on multi-year timescales owing to long-term ocean memory. Commun. earth Environ. 1, 26 (2020).

Tian, L., Yuan, S. & Quiring, S. M. Evaluation of six indices for monitoring agricultural drought in the south-central United States. Agric. For. Meteorol. 249, 107–119 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Monitoring winter wheat drought threat in Northern China using multiple climate-based drought indices and soil moisture during 2000–2013. Agric. For. Meteorol. 228, 1–12 (2016).

Zeng, X. Global Vegetation Root Distribution for Land Modeling. J. Hydrometeorol. 2, 525–530 (2001).

Orth, R. & Seneviratne, S. I. Predictability of soil moisture and streamflow on subseasonal timescales: A case study. J. Geophys Res-Atmos. 118, 10963–10979 (2013).

Dirmeyer, P. A., Halder, S. & Bombardi, R. On the harvest of predictability from land states in a global forecast model. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 123, 13,111–113,127 (2018).

Recalde-Coronel, G. C., Zaitchik, B., Pan, W. K., Zhou, Y. & Badr, H. Contributions of Initial Conditions and Meteorological Forecast to Subseasonal-to-Seasonal Hydrological Forecast Skill in Western Tropical South America. J. Hydrometeorol. 25, 709–733 (2024).

Li, H., Luo, L., Wood, E. F. & Schaake, J. The role of initial conditions and forcing uncertainties in seasonal hydrologic forecasting. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 114, 1–10 (2009).

Wood, A. W. et al. Quantifying Streamflow Forecast Skill Elasticity to Initial Condition and Climate Prediction Skill. J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 651–668 (2016).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The community earth system model version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model Earth Sy 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Richter, J. H. et al. Subseasonal Earth system prediction with CESM2. Weather Forecast. 37, 797–815 (2022).

Devanand, A. et al. Land use and land cover change strongly modulates land‐atmosphere coupling and warm‐season precipitation over the central United States in CESM2‐VR. J. Adv. Model Earth Sy 12, e2019MS001925 (2020).

Leeper, R. D., Petersen, B., Palecki, M. A. & Diamond, H. Exploring the use of standardized soil moisture as a drought indicator. J. Appl Meteorol. Clim. 60, 1021–1033 (2021).

Hoerling, M. et al. Causes and Predictability of the 2012 Great Plains Drought. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 130819115119008, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00055.1 (2014).

Kumar, S. et al. The GLACE-Hydrology Experiment: Effects of Land–Atmosphere Coupling on Soil Moisture Variability and Predictability. J. Clim. 33, 6511–6529 (2020).

Pegion, K. et al. The Subseasonal Experiment (S2S): A Multimodel Subseasonal Prediction Experiment. B Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 2043–2060 (2019).

Infanti, J. M. & Kirtman, B. P. Prediction and predictability of land and atmosphere initialized CCSM4 climate forecasts over North America. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 121, 12,690–612,701 (2016).

Sun, S., Bleck, R., Benjamin, S. G., Green, B. W. & Grell, G. A. Subseasonal forecasting with an icosahedral, vertically quasi-Lagrangian coupled model. Part I: Model overview and evaluation of systematic errors. Mon. Wea. Rev. 146, 1601–1617 (2018).

Zheng, Y. et al. Evaluation of reanalysis soil moisture products using cosmic ray neutron sensor observations across the globe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sc. 28, 1999–2022 (2024).

Tobin, K. J., Crow, W. T., Dong, J. & Bennett, M. E. Validation of a new root-zone soil moisture product: Soil MERGE. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 12, 3351–3365 (2019).

Quiring, S. M. et al. THE NORTH AMERICAN SOIL MOISTURE DATABASE Development and Applications. B Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 1441 (2016).

Baker, C. B. et al. Working toward a National Coordinated Soil Moisture Monitoring Network. (2022).

Entekhabi, D. et al. SMAP handbook–soil moisture active passive: Mapping soil moisture and freeze/thaw from space. (2014).

Raczka, B. et al. Improving CLM5.0 Biomass and Carbon Exchange Across the Western United States Using a Data Assimilation System. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020MS002421 (2021).

Kumar, S. et al. An agenda for land data assimilation priorities: Realizing the promise of terrestrial water, energy, and vegetation observations from space. J. Adv. Model Earth Sy 14, e2022MS003259 (2022).

Raeder, K. et al. A new CAM6+ DART reanalysis with surface forcing from CAM6 to other CESM models. Sci. Rep.-Uk 11, 16384 (2021).

Shi, P. et al. The 4DEnVar-based weakly coupled land data assimilation system for E3SM version 2. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 3025–3040 (2024).

Chikamoto, Y., Timmermann, A., Widlansky, M. J., Zhang, S. & Balmaseda, M. A. A drift-free decadal climate prediction system for the Community Earth System Model. J. Clim. 32, 5967–5995 (2019).

Miller, A. J. et al. Coupled ocean–atmosphere modeling and predictions. (2017).

Chikamoto, Y., Timmermann, A., Widlansky, M. J., Balmaseda, M. A. & Stott, L. Multi-year predictability of climate, drought, and wildfire in southwestern North America. Sci. Rep.-Uk 7, 6568 (2017).

Luo, F. et al. Summertime Rossby waves in climate models: Substantial biases in surface imprint associated with small biases in upper-level circulation. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 905–935 (2022).

Wehrli, K., Guillod, B. P., Hauser, M., Leclair, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Assessing the dynamic versus thermodynamic origin of climate model biases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 8471–8479 (2018).

Zheng, X. et al. The summertime precipitation bias in E3SM atmosphere model version 1 over the central United States. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 124, 8935–8952 (2019).

Sospedra-Alfonso, R. et al. Evaluation of Soil Moisture in the Canadian Seasonal to Interannual Prediction System, Version 2.1 (CanSIPSv2. 1). J. Appl Meteorol. Clim. 63, 143–164 (2024).

Nair, A. S., Counillon, F. & Keenlyside, N. Improving subseasonal forecast skill in the Norwegian Climate Prediction Model using soil moisture data assimilation. Clim Dynam, 1-20 (2024).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture-climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

Van Loon, A. F. Hydrological drought explained. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Water 2, 359–392 (2015).

Crausbay, S. D. et al. Defining ecological drought for the twenty-first century. B Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 2543–2550 (2017).

Mishra, A. K. & Singh, V. P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 391, 202–216 (2010).

Sheffield, J. & Wood, E. F. Drought : past problems and future scenarios. 9-38 (Earthscan, 2011).

Rodell, M. & Li, B. Changing intensity of hydroclimatic extreme events revealed by GRACE and GRACE-FO. Nat. Water 1, 241–248 (2023).

Qing, Y., Wang, S., Yang, Z.-L. & Gentine, P. Soil moisture− atmosphere feedbacks have triggered the shifts from drought to pluvial conditions since 1980. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 254 (2023).

Sharma, A., Wasko, C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. If precipitation extremes are increasing, why aren’t floods? Water Resour. Res 54, 8545–8551 (2018).

Berghuijs, W. R., Woods, R. A., Hutton, C. J. & Sivapalan, M. Dominant flood generating mechanisms across the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 4382–4390 (2016).

Merz, B. et al. Floods and climate: emerging perspectives for flood risk assessment and management. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1921–1942 (2014).

Materia, S. et al. Artificial intelligence for climate prediction of extremes: State of the art, challenges, and future perspectives. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, e914 (2024).

Lim, Y., Molod, A. M., Koster, R. D. & Santanello, J. A. The role of land-atmosphere coupling in subseasonal surface air temperature prediction. EGUsphere 2024, 1–15 (2024).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP climate forecast system version 2. J. Clim. 27, 2185–2208 (2014).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. The Community Land Model Version 5: Description of New Features, Benchmarking, and Impact of Forcing Uncertainty. J. Adv. Model Earth Sy 11, 4245–4287 (2019).

Tsujino, H. et al. JRA-55 based surface dataset for driving ocean–sea-ice models (JRA55-do). Ocean Model 130, 79–139 (2018).

Lombardozzi, D. L. et al. Simulating agriculture in the Community Land Model version 5. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 125, e2019JG005529 (2020).

Brunke, M. A. et al. Implementing and Evaluating Variable Soil Thickness in the Community Land Model, Version 4.5 (CLM4.5). J. Clim. 29, 3441–3461 (2016).

Thornton, P. E. et al. Modeling and measuring the effects of disturbance history and climate on carbon and water budgets in evergreen needleleaf forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 113, 185–222 (2002).

Thornton, P. E. & Rosenbloom, N. A. Ecosystem model spin-up: Estimating steady state conditions in a coupled terrestrial carbon and nitrogen cycle model. Ecol. Model 189, 25–48 (2005).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Martens, B. et al. GLEAM v3: satellite-based land evaporation and root-zone soil moisture. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1903–1925 (2017).

Reichle, R. H. et al. Assessment of MERRA-2 Land Surface Hydrology Estimates. J. Clim. 30, 2937–2960 (2017).

Miralles, D. G. et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 453–469 (2011).

Reichle, R. H. et al. Assessment and enhancement of MERRA land surface hydrology estimates. J. Clim. 24, 6322–6338 (2011).

Draper, C. et al. Estimating root mean square errors in remotely sensed soil moisture over continental scale domains. Remote Sens. Environ. 137, 288–298 (2013).

Hargrove, W. W. & Hoffman, F. M. Potential of multivariate quantitative methods for delineation and visualization of ecoregions. Environ. Manag. 34, S39–S60 (2004).

Kumar, S., Dirmeyer, P. A. & Kinter, J. Usefulness of ensemble forecasts from NCEP Climate Forecast System in sub‐seasonal to intra‐annual forecasting. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3586–3593 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We obtained the CESM2-S2S data from the Earth System Predictability (ESP) working group, which was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Weather Program Office/Climate Test Bed Program and by the National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR) under Cooperative Agreement 1852977. SK acknowledges the support of USDA-NIFA Awards # 2020-67021-32476 and 2023-70003-41354. We acknowledge the high-performance computing support from Auburn University Easley Cluster (hpcadmin@auburn.edu) and Cheyenne (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6RX99HX) provided by NSF NCAR’s Computational and Information Systems Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. conceived the research idea, secured funding, and supervised the students (Y.D., M.M., T.M.K.). J.R., A.G., and S.K. designed the CESM2-S2S experiment. A.G., T.K., and M.M. performed the CESM2-S2S experiments. Y.D. conducted the data analysis and visualization and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. S.K. and I.R. supervised the analysis. M.M. and M.E. performed the analysis of data assimilation experiments. B.R. and K.R. interpreted the data assimilation experiment. All authors contributed to manuscript development and discussions. S.K. integrated revisions and finalized the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, Y., Kumar, S., Maruf, M. et al. Enhancing sub-seasonal soil moisture forecasts through land initialization. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 100 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00987-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00987-0

This article is cited by

-

Skillful subseasonal soil moisture drought forecasts with deep learning-dynamic models

Nature Communications (2025)