Abstract

The performance of solution-processed 2D material networks is typically limited by intersheet junctions, which disrupt charge transport and prevent intrinsic nanosheet properties from scaling. Advances in processing and characterisation now allow direct junction engineering to tune the interlayer transport mechanisms. This Perspective reviews the current understanding of junctions, techniques for measuring their properties, and discusses engineering strategies for their tuning, aiming to unlock scalable fabrication of high-performance devices that mirror intrinsic 2D material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials have played a transformative role in the evolution of thin-film electronics, beginning with the isolation of graphene in 2004 and the solution synthesis of 2D nanosheets in 2008. Single-crystal semiconducting and metallic 2D nanosheets have demonstrated exceptional electronic and optoelectronic properties in devices such as field-effect transistors1, memory elements2, and photodetectors3. However, the central challenge in realising their technological potential lies in translating their remarkable intrinsic properties to large-area thin films suitable for commercial production. Scalable strategies broadly fall into two categories: growth-based methods, such as chemical vapour deposition (CVD), which yield large crystalline domains directly on rigid substrates; and solution-based techniques, such as inkjet printing or spin coating, which assemble dispersed nanosheets into continuous thin films.

While both approaches are capable of yielding functional thin films, they introduce fundamentally different structural artefacts that influence device performance. CVD-grown thin films are often interrupted by grain boundaries between crystalline domains4, whereas solution-processed nanosheet networks are limited by intersheet junctions between neighbouring nanosheets5. These discontinuities interrupt the relatively efficient charge transport within the basal plane, with hopping-based transport at the junction dominating the overall charge transport in the thin film6,7,8. This results in charge-carrier mobilities, a measure of how efficiently charge carriers move through a thin film, that can be over an order-of-magnitude lower than the single-crystal behaviour5. The grain boundary problem has existed for decades, particularly in ceramic systems9, and the strategies to engineer grain boundaries have been adapted for 2D systems, such as control over the boundary location10 or stitching fissures with molecular additives11. In contrast, despite each stage along the solution processing chain offering a point of intervention for tuning the intersheet junction properties, the notion of targeted engineering to affect junctions in nanosheet networks is far less developed.

Following advances in processing techniques for optimising the network structure, charge-carrier mobilities of solution-processed networks of MoS2 now rival those of CVD-grown thin films12,13. However, the macroscopic electrical performance consistently lags behind the intrinsic properties of individual nanosheets, with intersheet junctions still acting as the dominant rate-limiting step. To address this problem, one must first be able to quantify the junction resistance, and a characterisation technique has recently emerged that now allows its direct measurement in thin films14,15,16. Combining processing optimisation knowledge with the ability to measure junction resistance means the tools are now available to engineer junctions to eliminate their parasitic losses and pursue intrinsic 2D properties over large areas.

The goal of this Perspective is to review the current understanding of junctions in nanosheet networks, describe the technique for quantifying junction resistance, and demonstrate how physical or chemical approaches can be used to deliberately engineer junction transport behaviour. By consolidating existing knowledge with new insights, the aim is to initiate a broader discussion on junction engineering as a pathway towards the scalable production of large-area thin films that can showcase the intrinsic properties of 2D materials.

Nanosheets, networks, and junctions

Shortly after the mechanical exfoliation of graphene was first demonstrated, solution techniques were pursued as a processing route due to their scalability, cost-efficiency, versatility in both synthesis and deposition, compatibility with flexible substrates, and the ability to perform chemistry on dispersed nanosheets. A wide range of techniques have since been developed to process 2D van der Waals crystals in solution, including liquid-phase exfoliation17, electrochemical exfoliation18, shear mixing19, wet-jet milling20, and microfluidisation21. Each method is capable of producing monolayers, with the monolayer volume fractions being tied to the production method. Crucially, because solution-based approaches produce polydisperse systems, their combination with centrifugation allows the size selection of nanosheets22. Moreover, centrifugation facilitates the preparation of dispersions with concentrations suitable for diverse deposition methods23,24. Once deposited, the nanosheets assemble into a network with overlapping regions known as intersheet junctions5.

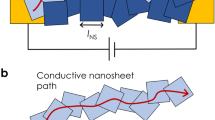

A defining challenge of thin-film devices is the presence of structural artefacts that impede charge transport. As shown in Fig. 1a, the structural artefacts in grown thin films are grain boundaries, which are typically defined by a misorientation angle between domains25. The charge-carrier mobility of the grown film is rate-limited by the inter-domain mobility, which tends to deviate substantially from the intra-domain mobility for misorientation angles below 20°, as shown in Fig. 1b. However, the critical structural artefact in solution-processed nanosheet networks is the intersheet junction, shown in Fig. 1c. Junction behaviour is influenced by a wide array of factors, including the contact area between sheets, the intersheet distance, or the presence of trapped impurities or residues. These features are in turn shaped by multiple stages of the solution processing chain: from the synthesis route and resulting nanosheet size, to the choice of solvent (e.g., NMP can polymerise during processing), the stabiliser used, the nanosheet concentration, the deposition method, and any post-deposition treatments. The resulting resistance at the junction rate-limits the electrical performance of the thin film, with macroscopic properties like the network conductivity tending to go inversely with increasing junction resistance (Fig. 1d)5.

a Growth processes such as chemical vapour deposition tend to create thin films that have grain boundaries, where the crystallography is discontinuous. This is typically characterised by the misorientation angle between the domains, where inter-domain mobility is typically lower than intra-domain mobility. b Plot of the change in intra-domain mobility and inter-domain mobility with increasing misorientation angle, with the image and data reproduced from ref. 25 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License. c Depositing nanosheets via spin coating, liquid-interface, or printing assembles individual nanosheets into a network. This means there will always be regions called junctions where the nanosheets overlap, and the transport method often changes. d Plot of the change in network conductivity with increasing junction resistance for three conductive 2D materials. Data reproduced from ref. 5 under the Springer Nature author reuse policy.

Despite the large number of variables affecting these junctions, the field has now matured to the point where many of these are understood well enough to allow the routine ambient fabrication of nanosheet networks with charge-carrier mobilities exceeding 10 cm2 V−1 s−1 16, with the ability to surpass 100 cm2 V−1 s−1 in a controlled atmosphere26. However, these values fall below the intrinsic nanosheet values, meaning junctions still play a rate-limiting role in influencing global electrical properties. Accordingly, the relative values of the resistance at the junction, RJ, and the resistance within the nanosheet itself, RNS, can act as a quality factor: the ratio of RJ/RNS is a measure of how closely the network properties approach the intrinsic properties of the constituent 2D material. To experimentally improve this quality factor, it is therefore essential to be able to measure both nanosheet and junction resistances independently and with ease.

Measuring junction and nanosheet resistances

Traditionally, resistance between nanosheets has been measured using techniques such as conductive-AFM27. While effective at probing individual junctions, such approaches are impractical for extracting an average junction resistance across a large-area nanosheet network. The wide variety of junction configurations within a thin film, combined with its macroscopic scale, makes direct comparison across different networks by such methods infeasible. To address this, impedance spectroscopy provides a powerful alternative by exploiting the intrinsic capacitance at each junction, which imparts a frequency-dependent response to the network14. Fig. 2a shows an impedance spectrum for an MoS2 network, with both the real (Z′) and imaginary (–Z′′) components resembling the response of a Randles circuit. The equivalent circuit, shown adjacent, comprises a series resistance, RS, and a parallel resistor–capacitor pair (RP and CP, respectively). In a nanosheet network, RS includes the sum of all the nanosheet resistances, while RP and CP correspond to the absolute junction resistance and capacitance.

a Impedance spectrum of a nanosheet network of MoS2, showing the real (Z’) and imaginary (−Z”) impedances. These spectra are a function of channel length, L, the channel width, w, the porosity, P, and nanosheet thickness, tNS, as shown adjacent. b The same spectra converted to that of a nanosheet–junction pair characteristic of the network using Eq. 1 in the main text. These spectra can now be fitted with Randles circuit equations to extract values of RNS, RJ, and CJ, with n being the width of the distribution of these values. c Temperature-dependent impedance measurements on an MoS2 network, showing decreasing junction resistance (low frequency) and increasing nanosheet resistance (high frequency) with increasing temperature. d The junction resistance, RJ, extracted from the data in c plotted against 1/T, showing a transition from 3D variable-range hopping at low temperature to activated behaviour at higher temperature. e The nanosheet resistance, RNS, extracted from c plotted against temperature. The data fit a phonon-limited transport model, with α = 1.1. All data shown here are reproduced from ref. 14 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License.

However, because these values reflect the impedance of the entire film, they are influenced by variables such as device channel dimensions, network porosity, and nanosheet size. To obtain an intrinsic measure of junction behaviour for a given thin film, analogous to converting resistance into resistivity, these impedance values can be transformed into the characteristic impedance of a representative nanosheet–junction pair using the following equation

where ρNet is the resistivity of the network, PNet is the network porosity, tNS is the nanosheet thickness, nNS is the nanosheet carrier density, and lNS is the nanosheet length, with these variables depending on both the 2D material and the network structure. For a full derivation of this expression, see the Supplementary Information in ref. 14. The purpose of applying this transformation is to generate spectra characteristic of the network’s fundamental nanosheet–junction building block, from which average nanosheet and junction resistances can be extracted. The ratio RJ/RNS is then easily calculated, indicating whether the junctions or nanosheets are the dominant performance bottleneck.

Applying this conversion (described in detail in ref. 14), the spectra in Fig. 2b now represent the behaviour of an average nanosheet–junction pair. After this rescaling, the high-frequency plateau now corresponds to the average nanosheet resistance, RNS, while the low-frequency plateau now corresponds to the sum of the average nanosheet resistance and the average junction resistance, RNS + RJ. To extract these values, the spectra can be fitted using standard Randles circuit models14, with each property assigned a distribution factor, n. A value of n = 1 implies perfect uniformity across the network (i.e., all nanosheets or junctions have exactly the same resistance), whereas increasing deviation from unity reflects increasing disorder. Importantly, extracting the average nanosheet resistance also allows an estimation of average nanosheet mobility, eliminating the need for time-consuming single-nanosheet gating experiments or specialised spectroscopic measurements.

A key strength of this technique lies in its ability to simultaneously extract both nanosheet and junction resistances, meaning temperature-dependent impedance measurements combined with charge transport models can distinguish the transport processes associated with the nanosheet and the junction within a thin film. As shown in Fig. 2c, increasing temperature causes a clear change in the shape of the Z′ curve: the low-frequency plateau drops, reflecting a decrease in junction resistance, while the high-frequency plateau increases owing to increasing nanosheet resistance. By plotting these resistance changes against temperature and fitting to standard transport models, such as variable-range hopping or thermal activation7,14,28, the respective transport processes of nanosheets and junctions can be decoupled from this single macroscopic measurement.

Figure 2d shows junction transport evolving from three-dimensional variable-range hopping (3D VRH) at low temperatures to thermally activated behaviour above 200 °C, with their respective characteristic temperature, T0, and activation energy, EA, shown inset. Meanwhile, Fig. 2e shows nanosheet resistance scaling with temperature to the power of ~1.1, consistent with phonon-limited, band-like transport29. This means that carrier transport through a network alternates between hopping (relatively inefficient) and band-like (relatively efficient) conduction mechanisms. Similar spatial variations in transport have been reported for MoS2, where thermal activation in the basal-plane transitions to variable-range hopping at the contacts30.

There are two levels of analysis presented here. First, a simple room-temperature impedance spectrum suffices to reveal the relative magnitudes of nanosheet and junction resistances and to estimate RJ/RNS. This evaluates how similar the thin-film properties are to those of the nanosheets and can be thought of as a measure of how well optimised the network structure is. Second, temperature-dependent impedance outputs fitted with transport models reveal the specific transport processes within the nanosheets and across the junctions. To realise intrinsic monolayer properties over large areas, the junction transport itself must be engineered to mimic that within the nanosheet.

Junction engineering in nanosheet networks

Charge-carrier propagation through a nanosheet network is spatially constrained, with intersheet junctions acting as rate-limiting steps due to parasitic hopping losses. While in-plane transport within each nanosheet can proceed via band-like conduction, carriers moving between sheets rely on out-of-plane hopping6,7,8. This raises an important question: can in-plane transport behaviours ever occur at a junction? If such a regime could be achieved, monolayer behaviour could be produced over large areas, and further performance gains would then depend on improving the material itself. This challenge centres on the stark anisotropy in in-plane versus out-of-plane conduction common to bulk crystals of layered materials, which often exceeds two orders of magnitude due to weak van der Waals interlayer coupling31,32,33,34. There is an equivalence between transport in bulk crystals and intersheet junctions whereby the carriers must hop between layers; however, there is also a distinction in that solution processing offers a variety of strategies that could be used to tune interlayer transport.

The optimal processing conditions, from synthesis to deposition, for minimising structural losses have now been largely figured out and, as a result, solution-processed nanosheet networks are now beginning to approach the performance of bulk crystals35. It is widely understood that the critical nanosheet dimension for controlling junction resistance is thickness, with thinner nanosheets forming more intimate contact5,27,36. Furthermore, the deposition process must be capable of producing highly aligned nanosheets12,37,38, while any post-treatment must remove as much residual solvent or stabiliser as possible and reduce the porosity5,39. This set of protocols, which now routinely produces mobilities and conductivities approaching those of the individual nanosheets12,14,16, can be considered “processing optimisation” of the thin film, and the efficacy of a protocol can be rapidly quantified using the technique discussed in Fig. 2b for obtaining RJ/RNS. The charge-carrier transport in a fully optimised structure would mimic bulk crystal conditions in that interlayer contact is intimate, but carriers always hop between layers.

Such a condition may be sufficient for many applications, but the power of 2D materials lies in their behaviour in the mono- to few-layer limit, and this is very often the behaviour we seek to realise at scale. However, taking the example of a junction formed between two monolayers, the junction itself becomes a bilayer system where the interlayer transport is limited to hopping. Unlike processing optimisation techniques, which can only create better conditions for hopping, reproducing in-plane transport at the junction requires targeted engineering strategies capable of altering the transport mechanism itself. Eliminating junction losses for properties such as charge-carrier mobility is a high-gain goal, and the ability to engineer such a condition demonstrates the potential for 2D materials to surpass the traditional limitations of amorphous thin films. This is the ultimate aim of the junction-engineering strategies that follow.

Residue removal

An important structural optimisation step prior to engineering junctions is to ensure that the interfaces are clean. Solution processing inevitably introduces impurities that hinder efficient charge transfer by inserting physical barriers and scattering sites between nanosheets. Typical contaminants include residual solvents or stabilising surfactants such as sodium cholate or polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). As detailed in recent reviews5,40,41, there is a wide range of techniques available to produce clean intersheet interfaces, whose choice is primarily dependent on compatibility with the processing route. Common methods for cleaning the nanosheets post-deposition include acid washing with agents such as bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (TFSI) or thermal annealing. For instance, TFSI treatments have been shown to dissolve PVP from solution-processed MoS2 networks, substantially enhancing mobility in field-effect devices37,42, while also healing sulphur vacancies that result in thousand-fold increases in the on:off ratio13. Likewise, Li-TFSI treatments have been reported to double the photoluminescence yield of MoS2 and WS2 monolayers, suggesting effective impurity removal and electronic passivation43. In a similar vein, ultrasonication at megahertz frequencies can also produce ultraclean nanosheets as evidenced by photo- and electroluminescence44, suggesting that such high frequencies can desorb residual ligands while the nanosheets are still in dispersion.

Thermal annealing provides a complementary approach by volatilising residual solvents and decomposing polymer surfactants, causing the nanosheets to collapse into denser, more conductive networks5,39,40. However, as noted in refs. 37,42, annealing can also alter carrier concentrations since mobility decreases have been observed at 300 °C compared with 200 °C, highlighting the potential doping effects of impurity removal. Interestingly, not all residual ligands are necessarily detrimental. Recently, ref. 45 showed that residual PVP within an MoS2 network can be crosslinked to form chemically and structurally robust films that can still achieve mobilities in excess of 20 cm2 V−1 s−1. While a clean interface is a requisite for efficient interlayer charge transfer, unless the residual ligands themselves are conductive, their presence (or even absence) cannot produce conditions where RJ < RNS or produce interlayer band-like transport.

Orbital-overlap engineering

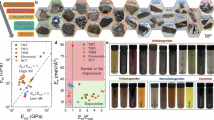

A simple strategy to improve charge transport at the junctions is to choose materials with significant orbital penetration into the interlayer gap. In TMDs, out-of-plane electronic coupling is governed in part by the extent to which the hybridised chalcogen p-orbitals and metal d-orbitals protrude beyond the basal plane. As one moves down the chalcogen family from sulphur to selenium to tellurium, the radial extent of the p-orbitals increases, enhancing their spatial overlap across adjacent nanosheets. This trend is reflected in a rising chalcogen p-orbital contribution near the valence band maximum with increasing chalcogen size46, resulting in an exponential relationship between conductivity and bandgap47, as shown in Fig. 3a. Concurrently, the metal d-orbitals (Mo 4 d and W 5 d) show enhanced hybridisation with these p-states, with the effect of comparable in-plane conductivities for MoTe2 and WSe2. This hybridisation reaches an extreme in WTe2, where a slight overlap between the conduction and valence bands gives rise to semimetallic behaviour48, and a conductivity far higher than MoSe2 or WSe2.

a Material choice: the chalcogen orbitals extend further into the van der Waals gap as one moves from S to Se to Te, enhancing interlayer orbital overlap and increasing out-of-plane conductivity. The plot shows the room-temperature in-plane conductivity as a function of bandgap energy for various TMDs, with WTe2 exhibiting semimetallic behaviour and the highest conductivity. Data reproduced from ref. 47. b Applied pressure: external pressure reduces the interlayer spacing and increases orbital overlap, leading to significant improvements in interlayer conductivity. For MoS2 and MoSe2, a continuous increase in conductivity is observed with increasing pressure, with MoS2 showing a structural transition from the 2HA to 2HC phase ~20 GPa. Data reproduced from ref. 49 under license number RNP/25/SEP/096928 and ref. 50 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License.

Noting that the out-of-plane conductivity is approximately 100 times lower than in-plane31,32, Fig. 3 would imply that MoTe2 and WSe2 would be good candidates for pursuing more efficient charge tunnelling or hopping, effectively reducing intersheet resistance. However, while this enhanced orbital overlap improves out-of-plane conductivity, it also introduces trade-offs, particularly in switching performance. The greater interlayer coupling associated with heavier chalcogens tends to raise the baseline conductivity of the network, leading to increased off-currents and a corresponding degradation in the on:off ratio16,47. For logic or switching applications, where high on:off ratios are essential, the use of Te-based TMDs such as MoTe2 may therefore be less desirable despite their favourable intersheet junction characteristics. In addition, the mobility anisotropy remains, meaning material choice alone cannot facilitate RJ < RNS.

With a material selected, the next most intuitive strategy for engineering junction transport via orbital overlap is to reduce the intersheet distance. Several studies have shown that the conductivity of TMDs, such as MoS2 and MoSe2, increases dramatically under applied pressure. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, applying pressure in the GPa range leads to conductivity enhancements of up to five orders of magnitude49,50. Distinct from calendaring, which reduces the network porosity, improvements at GPa pressures are primarily due to the reduction in interlayer spacing, which occurs more rapidly than any change to the intralayer atomic structure. With increasing compression, the conduction band edge shifts as the contribution from the sulphur pZ-orbitals grows, alongside enhanced involvement of the molybdenum dZ2-orbitals. While little data is available on the change in conductivity with pressures in the MPa range or lower, the increase in conductivity between 0 and 1 GPa in the MoSe2 data suggests this range has a comparatively small impact on the intersheet distance.

This pressure-driven behaviour ultimately induces metallisation. For MoS2, a transition to a metallic state occurs around 20 GPa, accompanied by a first-order structural phase transition from the semiconducting 2HC phase to the metallic 2HA phase49,51. In MoSe2, band overlap does not begin until around 40 GPa, but occurs without a structural phase transition due to the wider selenium p-orbitals allowing greater orbital hybridisation within the same crystal structure50, with similar structural resilience predicted for MoTe252.

Metallising the junctions via reduced intersheet distance while retaining the semiconducting character of the basal plane would represent an ideal scenario for achieving RJ < RNS while producing metallic transport across the junction. Additionally, the inherently thin nature of nanosheet networks, often <10 nm thick, offers flexibility in pressure distribution that could benefit the design of highly sensitive devices. However, applications with GPa-range pressures are likely to remain limited to specialised domains, such as ultrahigh-pressure sensing, ballistic impact detectors, or exploratory studies in diamond anvil cell systems.

Chemical engineering

Rather than compress the nanosheets together, strategies have also been pursued to introduce ways to chemically bridge the junction between nanosheets of sulphur-based TMDs. One approach involves the creation of a metal–metal contact using metal nanoparticles. With the nanosheets in dispersion, the edge and defect sites of nanosheets of WS2 or MoS2 can easily be chemically functionalised with particles such as gold53,54,55, palladium56,57, or platinum58. By mixing chloroauric acid or potassium tetrachloropalladate into a dispersion of nanosheets, spontaneous reactions occur predominantly at vacancy defects at the nanosheet edges or at terraces on the basal plane, leading to the nucleation of nanoparticles whose size and quantity are a function of reaction time, temperature, and molar stoichiometric ratio53, and also the defect density along the edges59. This is in contrast to graphene, where nucleation tends to occur along wrinkles60.

The importance of the preferential edge-functionalisation gives rise to two scenarios when considering how this affects junctions. In the first (Point 1, Fig. 4a), a nanoparticle on the edge of the top nanosheet makes contact with a nanoparticle on the lower nanosheet, forming a direct metal–metal junction, and in the second (Point 2, Fig. 4a), a nanoparticle on the top nanosheet contacts the basal plane of the lower nanosheet. Point 1 in Fig. 4a presents a promising pathway for improving junction transport. When gold, platinum, or palladium nanoparticles bridge adjacent nanosheets, the resulting junction forms a metallic conduit that could bypass the need for hopping across the van der Waals gap. In this case, the junction resistance would no longer be dominated by the interfacial barrier but instead by the intrinsic resistance of the nanoparticle and the quality of mechanical contact. However, given the fact that nanoparticles form along nanosheet edges (in the absence of terraces), this means there will be only two metal–metal contact points per junction.

a Functionalising the edges of nanosheets while in dispersion can easily be achieved via mixing with acids, as shown in the TEM image. When then deposited into a network, the functional particle may induce metal–metal contact between nanosheets (Point 1) or metal–basal plane contact (Point 2), where conductivity scales with nanoparticle loading. Data and TEM image reproduced from ref. 57 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License. b Sulphur vacancies in adjacent nanosheets can be bridged using dithiol molecules, which leads to over 10× improvements in network mobilities. Lateral heterostructures tend to produce even larger improvements. Graphs reproduced from refs. 65,66 under author reuse policies.

Given the metallic nature of the intersheet contact, one might expect an overall enhancement in charge-carrier mobility. However, studies on CVD-grown monolayer MoS₂ with edge-functionalised gold nanoparticles have shown a modest decrease in mobility compared to pristine films59, alongside a positive shift in threshold voltage59,61. This behaviour indicates p-type doping caused by redox reactions, though the role of nanoparticle loading on mobility has not been systematically explored. However, it has also been reported that functionalisation via galvanic displacement can produce undoped nanosheets, where here the network conductivity scales with increased nanoparticle loading, with the highest loading increasing the conductivity by six orders of magnitude (Fig. 4a)57.

The small diameter, d, of the nanoparticles (2–10 nm)57,59 necessitates consideration of the current density funnelled through each one along a current path. To model this simply, we take the device in Fig. 2c and assume each junction has two connected nanoparticle bridges, thus creating the conditions where RJ < RNS. The resistance of the device would be dominated by the resistance of the nanosheets, so with a junction-to-nanosheet resistance ratio, RJ/RNS, of ~1014, this gives a resistance of ~400 Ohms at room temperature. To estimate the current through a single channel of nanosheets, we would divide the current by the ratio of network cross-section, wNettNet, to nanosheet cross-section, wNStNS, while also noting that only some channels will carry current, meaning an efficiency factor, η, should be included. The resulting current density per bridge can then be approximated as

Assuming that only 20% of the current paths are active62 with each metallic bridge composed of 5 nm gold nanoparticles, this yields J = 1.5 mA μm−2 at 1 V. To prevent breakdown in the form of electromigration or excessive Joule heating, modern integrated circuit design rules typically limit DC current density to 0.5–1 mA μm−2 for standard copper interconnects63. To avoid degradation, this would place an upper limit on the drive voltage for this device in the range of 330–660 mV. This is a rough estimate that neglects porosity but demonstrates the need to account for current density when using nanoparticle bridges.

Regarding Point 2 in Fig. 4a, it has been reported that noncovalently adsorbed gold nanoparticles on the basal plane increase in-plane resistance and cause positive shifts in threshold voltage with increasing nanoparticle coverage61. This behaviour has been attributed to electron depletion around the nanoparticle, resulting in p-doping, the formation of a localised Schottky barrier, and reduced mobility due to a disordered potential landscape. Upon reaching a certain size, percolation behaviour takes over, and the conductivity increases by orders of magnitude64. However, edge-functionalisation in dispersion offers an important distinction: the nanoparticles are already reduced prior to deposition and are more likely to form contact without inducing Schottky barriers. Instead, their effect at the perimeter of the junction may be limited to charge scattering.

Since Point 1 and Point 2 are likely to occur at a given junction, a trade-off emerges, and the number of nanoparticles must be optimised to balance two competing effects: the beneficial formation of metallic bridges (Point 1) and the detrimental charge scattering at the junction entrance (Point 2). Ideally, one would maximise the number of nanoparticles to increase the probability of forming conductive metal–metal contacts, while simultaneously minimising the density of particles that contribute to scattering and localised potential fluctuations. Achieving this balance is key to enhancing intersheet charge transport without compromising overall network performance.

Another promising strategy for chemically engineering the junctions involves the use of molecular linkers such as dithiols. After forming a nanosheet network, soaking the film in a dithiol-containing solution causes the sulphur atoms on the dithiol to occupy vacancies left by chalcogen atoms along the edges of the TMDs, both repairing and functionalising the defects. However, the other –SH group on the dithiol is also free to bond with a neighbouring nanosheet, effectively tethering them through covalent bonds, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Compared to metal nanoparticles, dithiols offer greater tunability: by varying the molecular backbone or terminal groups, one can tailor the electronic properties, improve network cohesion, and minimise the risk of unintentional network shorting with increased loading.

This approach was demonstrated in nanosheet networks of liquid-phase exfoliated MoS2 and WS2, where the on:off ratio, charge-carrier mobility, and switching speed were each improved by an order of magnitude through the formation of covalent bridges using conjugated 1,4-benzenedithiol molecules (Fig. 4b)65. Similarly, stepwise deposition of MoS2 followed by WS2 with an intermediate functionalisation step has been shown to yield mobilities higher than those of networks composed of a single material, implying that in-plane heterostructures may also be a strategy to improve charge transport (Fig. 4b)66. However, for devices whose operation relies on vacancy density, such as memristors67, molecular healing of vacancies will likely have detrimental consequences on device outputs.

Chemical strategies for reducing junction resistance show great promise for creating the condition where RJ < RNS while also potentially changing transport behaviour. Edge functionalisation can create metallic conduits between basal planes; however, the mobility of metals is typically in the range of 20–50 cm2 V−1 s−1. This means the metal bridges themselves may act as bottlenecks for nanosheet networks such as InSe where the mobility is greater than 50 cm2 V−1 s−1, which may place a ceiling on improvements in junction behaviour. In addition, the significant increase in baseline conductivity (i.e., the off current) means loading must be carefully optimised to retain appreciable on:off ratios.

Concerning molecular bridges, the covalent bonding of a semiconducting molecule to the nanosheet means a mobility ceiling may not exist for chemical cross-linking. The use of a thiol-based bridge reduces the activation energy associated with hopping by a factor of two, resulting in a tenfold increase in mobility65. If such an increase is unbounded, then applying this technique to the MoS2 in Fig. 2 with RJ/RNS of ~10 may be able to bring the junction resistance into range of the individual nanosheets. Regarding transport modulation, coherent transport tends to occur in molecules shorter than 3 nm68 with tunnelling often dominating at molecular length scales69. These constraints allow for a broad range of potential molecular candidates, while selecting molecules with σ-delocalised orbitals (e.g., Se-functionalised aromatics) can further tune the transport behaviour of the molecule itself70. With the demonstrated viability of molecular bridging in nanosheet networks, bringing the body of knowledge from single-molecule junctions to bear on the challenge of junction-limited nanosheet networks offers a substantial toolbox for achieving targeted design of junction transport.

Outlook

The consolidation of a number of techniques under the umbrella of junction engineering promises to overcome fundamental transport bottlenecks in nanosheet networks. Table 1 outlines the relative strengths and weaknesses of each technique, but however effective a technique may be, it must be compatible with scalable processing to have value. For example, methods for removing residues (e.g., acid washing or thermal treatments) are already well established, while metal functionalisation can take place via solution mixing while the nanosheets are in dispersion. Similarly, soaking a thin film in a thiol-containing solution to create chemical crosslinks is an easily scalable process, and although material selection is straightforward, the bandgap decreases with increasing chalcogen size, a trend that is accompanied by roughly a tenfold rise in cost from S to Se to Te71. While the techniques discussed so far are experimentally validated, one can look to more conceptual junction engineering strategies by speculating on how the relative twist and stacking of nanosheets, long studied in moiré bilayers, might influence transport in disordered networks.

Orientation engineering: the moiré problem

In solution-processed networks, where nanosheets are deposited with random orientations, a broad distribution of twist angles at the junctions is unavoidable. As a result, it is highly likely that some junctions will exhibit moiré patterns, which are also known to form in folded nanosheets72. The formation of moiré superlattices facilitates variation in electronic and optical properties, along with emergent phenomena such as superconductivity, correlated insulating states, and orbital magnetism73. While these effects are of great interest for unlocking new functionalities in 2D systems, their presence and influence in disordered nanosheet networks remain unclear, particularly regarding how twist angle affects carrier transport. In this section, we explore the current understanding of twist angle effects in the context of intersheet junctions.

Moiré patterns form when two periodic lattices are overlaid with a relative twist or slight mismatch in lattice constants, creating a larger-scale interference pattern. In 2D materials, this occurs when one layer is rotated or strained relative to another, generating a periodic modulation of the atomic registry. The moiré wavelength, defined as the centre-to-centre distance between the repeating features shown in Fig. 5a, increases as the twist angle between two 2D layers decreases, reaching hundreds of nanometres at small misalignments74,75. Importantly, rotation also introduces steric effects that influence stacking. Figure 5b shows the range of possible MoS2 stacking configurations, from high-energy AA3 and AB3 to low-energy AA1 and AB1, with intermediate states at other angles76. AA1 and AB1 occur at 0° and 60°, respectively, with AB1 known as natural, or Bernal, stacking. Although nanosheets would energetically prefer to slide into one of these low-energy configurations, the limited junction area relative to the basal plane, as shown in Fig. 5a, restricts their ability to reorient freely.

a SEM image of a junction in an MoS2 network with a possible twist angle highlighted, showing the emergence of long-range periodicity with increasing angle. Schematic reproduced from ref. 77 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License. b Schematic stacking configurations from 0° to 60° twist, including high-symmetry registries (e.g. AA3, AB1, AB2) relevant to interlayer orbital alignment. Reproduced from ref. 76 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License. c Variation in van der Waals gap relative to AB stacking with twist angle (data reproduced from ref. 79). d Change in bandgap as a function of twist angle, with the two low energy configurations having the lowest gap. Reproduced from ref. 76 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License. e Change in hole effective mass with twist angle (data reproduced from ref. 79). f Ratio of interlayer resistance relative to the resistance at 0° (R/R₀) versus twist angle for graphite/graphene (data reproduced from ref. 80). g Ratio of interlayer resistance relative to the resistance at 0° (R/R₀) versus twist angle for graphene/MoS₂ heterostructures (data reproduced from ref. 81 under a CC Attribution 4.0 International License).

Two key factors influence charge transport in twisted nanosheet junctions: the sterically-induced increase in interlayer spacing and the formation of moiré patterns. While intersheet thermal transport shows only a weak dependence on twist angle77, the variation in interlayer distance alone significantly impacts electrical transport, due to its strong influence on conductivity and bandgap, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a. Figure 5c shows the interlayer gap increases by as much as 30% across most twist angles compared to AB stacking, amplifying the barrier for intersheet charge transport. This results in an increase in bandgap as shown in Fig. 5d, with angles between 0° and 60° exhibiting bandgap increases up to 20% higher than either of the high-symmetry arrangements76,78. Additionally, the emergence of moiré patterns leads to band flattening around the K points and a corresponding increase in carrier effective mass (Fig. 5e)79.

Changes in interlayer resistance as a function of twist angle have been measured for carbon systems. At a graphene/graphite interface, interlayer resistance increases by up to 30× for twist angles near 30° relative to the high-symmetry configurations at 0° and 60° (Fig. 5f)80. Similarly, a graphene/MoS2 junction shows a 5× increase in resistance at 30° (Fig. 5g)81. Crucially, the resistance increase spans a broad angular range: nearly all angles between 0° and 60° are affected in the graphene/graphite system, and ~50% in the graphene/MoS2 system. To the best of the author’s knowledge, the interlayer resistance of an MoS2 bilayer system has not been reported as a function of twist angle, but the following comments can be made.

While both tunnelling and hopping processes can occur simultaneously82, with tunnelling efficiency maximised when lattice points lie above one another, hopping is the dominant junction transport process in nanosheet networks7,14. Under the 3D VRH regime for carrier hopping between nanosheets, junction resistance can be described as ref. 14

with

where lJ is the interlayer distance, ξ is the localisation length, d0 is the monolayer thickness, and m is the effective carrier mass. The rotation-induced increase in interlayer distance (Fig. 5c) will affect the first term in Eq. (3), leading to an increase in RJ. However, the junction resistance also depends on the localisation length through two exponential terms, making it highly sensitive to changes. In twisted bilayer systems, the moiré wavelength increases as the twist angle decreases, leading to a deeper moiré potential at small angles that can reach depths of up to 300 meV in heterobilayer systems83. Near magic angles (3–5° for TMDs)84, the moiré bands flatten85, increasing the effective mass in the junction and localising charge carriers75. Notably, this trap depth lies within the range of activation energies (50–200 meV) reported for nanosheet networks7,14,65,86.

Concerning nanosheet networks in which junctions can be considered homobilayer systems, this suggests that all junctions with twist angles other than 0° or 60° will exhibit higher junction resistance owing to both steric and moiré effects, with the range of 2–7° likely corresponding to the highest values. While such behaviour is desirable for achieving Mott insulating or superconducting states75,87, it remains unclear how to control twist angles at intersheet junctions to optimise charge transport. However, although the angle itself may not be tunable in solution-processed networks, studies in bilayer graphene have shown that flat band formation can be disrupted via doping88,89,90, which may provide a route to mitigating twist-induced junction resistance in TMD systems.

As a conceptual technique, it is not clear if orientation engineering alone can achieve the condition where RJ < RNS or realise band-like transport at a junction. However, assuming all twist angles are present in a graphene nanosheet network, Fig. 5f shows that the average junction resistance across the entire network, R/R0, is ~11.5× higher than if all junctions were aligned at 0° or 60°. From ref. 38, the average RJ/RNS for a graphene network is ~1.5, suggesting that orienting all the intersheet angles to either 0° or 60° can deliver the scenario where RJ < RNS. For MoS2, ref. 14 reports an average RJ/RNS of ~10. Assuming the same R/R0 of ~11.5 across all angles, this again suggests that control over relative intersheet angles could create the condition where RJ < RNS and eliminate the junction bottleneck, although temperature-dependent electrical measurements as a function of angle would be required to confirm any change in transport process.

Future challenges

Future challenges for junction engineering lie in moving beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations toward integration with scalable processing methods. While techniques such as residue removal, pressure, chemical cross-linking, and nanoparticle functionalisation have shown clear reductions in junction resistance, their implementation must be compatible with industrially relevant deposition routes such as printing, spin coating, and liquid–liquid assembly. Processing environments inevitably introduce variability that can strongly influence the effectiveness of any junction-level modification. Thus, a key challenge is developing protocols that retain their efficacy across large areas and under the dynamic conditions of solution deposition, while maintaining reproducibility and uniformity at scale.

Achieving junction resistances comparable to nanosheet resistances, the regime where RJ/RNS ~1, represents a critical benchmark for the field. This implies the network structure is no longer the rate-limiting factor. However, to eliminate parasitic junction behaviours and allow the intrinsic properties of the nanosheets to dominate at the network level, charge transport processes at the junctions need to be engineered to match those of the nanosheet. Reaching this regime requires not only minimising disorder and barriers at the junctions, but also ensuring that these improvements remain stable under operating conditions. The path forward will involve tailoring chemical, structural, and orientational strategies to work together with scalable deposition techniques and finally bridge the gap between nanoscale performance and practical device integration.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bandurin, D. A. et al. High electron mobility, quantum Hall effect and anomalous optical response in atomically thin InSe. Nat. Nanotech. 12, 223–227 (2017).

Sangwan, V. K. et al. Gate-tunable memristive phenomena mediated by grain boundaries in single-layer MoS2. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 403–406 (2015).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nano 9, 780–793 (2014).

Yao, W., Wu, B. & Liu, Y. Growth and grain boundaries in 2D materials. ACS Nano 14, 9320–9346 (2020).

Kelly, A. G., O’Suilleabhain, D., Gabbett, C. & Coleman, J. N. The electrical conductivity of solution-processed nanosheet networks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 18 (2021).

Kelly, A. G. et al. All-printed thin-film transistors from networks of liquid-exfoliated nanosheets. Science 356, 69–73 (2017).

Piatti, E. et al. Charge transport mechanisms in inkjet-printed thin-film transistors based on two-dimensional materials. Nat. Electron. 4, 893–905 (2021).

Ippolito, S. et al. Unveiling charge-transport mechanisms in electronic devices based on defect-engineered MoS2 covalent networks. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211157 (2023).

Waser, R. & Hagenbeck, R. Grain boundaries in dielectric and mixed-conducting ceramics. Acta Mater. 48, 797–825 (2000).

Wang, X. et al. Grain-boundary engineering of monolayer MoS2 for energy-efficient lateral synaptic devices. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102435 (2021).

Han, B. et al. Welding 2D semiconducting crystals by covalent stitching of grain boundaries in WS2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 24162–24170 (2025).

Neilson, J. et al. Production of ultrathin and high-quality nanosheet networks via layer-by-layer assembly at liquid–liquid interfaces. ACS Nano 18, 32589–32601 (2024).

Kwon, Y. A. et al. Wafer-scale transistor arrays fabricated using slot-die printing of molybdenum disulfide and sodium-embedded alumina. Nat. Electron. 6, 443–450 (2023).

Gabbett, C. et al. Understanding how junction resistances impact the conduction mechanism in nano-networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 4517 (2024).

Caffrey, E. et al. Using electrical impedance spectroscopy to separately quantify the effect of strain on nanosheet and junction resistance in printed nanosheet networks. Small 21, 2406864 (2025).

Carey, T. et al. Electronic properties and circuit applications of networks of electrochemically exfoliated 2D nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 16, 9038 (2025).

Backes, C. et al. Equipartition of energy defines the size–thickness relationship in liquid-exfoliated nanosheets. ACS Nano 13, 7050–7061 (2019).

Yang, R. et al. Synthesis of atomically thin sheets by the intercalation-based exfoliation of layered materials. Nat. Synth. 2, 101–118 (2023).

Paton, K. R. et al. Scalable production of large quantities of defect-free few-layer graphene by shear exfoliation in liquids. Nat. Mater. 13, 624–630 (2014).

Castillo, A. E. D. R. et al. High-yield production of 2D crystals by wet-jet milling. Mater. Horiz. 5, 890–904 (2018).

Large, M. J. et al. Large-scale surfactant exfoliation of graphene and conductivity-optimized graphite enabling wireless connectivity. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000284 (2020).

Backes, C. et al. Production of highly monolayer enriched dispersions of liquid-exfoliated nanosheets by liquid cascade centrifugation. ACS Nano 10, 1589–1601 (2016).

Kelly, A. G. et al. Tuneable photoconductivity and mobility enhancement in printed MoS 2 /graphene composites. 2D Mater. 4, 041006 (2017).

Hu, G. et al. Functional inks and printing of two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 3265–3300 (2018).

Ly, T. H. et al. Misorientation-angle-dependent electrical transport across molybdenum disulfide grain boundaries. Nat. Commun. 7, 10426 (2016).

He, J. et al. Solution-processed wafer-scale indium selenide semiconductor thin films with high mobilities. Nat. Electron. 8, 244–253 (2025).

Nirmalraj, P. N., Lutz, T., Kumar, S., Duesberg, G. S. & Boland, J. J. Nanoscale mapping of electrical resistivity and connectivity in graphene strips and networks. Nano Lett. 11, 16–22 (2011).

Wang, F. et al. Inter-flake quantum transport of electrons and holes in inkjet-printed graphene devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007478 (2021).

Jariwala, D. et al. Band-like transport in high mobility unencapsulated single-layer MoS2 transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 173107 (2013).

Peng, S. et al. Metal-contact-induced transition of electrical transport in monolayer MoS2: from thermally activated to variable-range hopping. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, 1900042 (2019).

Cunningham, G. et al. Photoconductivity of solution-processed MoS2 films. J. Mater. Chem. C. 1, 6899–6904 (2013).

Barwich, S. et al. On the relationship between morphology and conductivity in nanosheet networks. Carbon 171, 306–319 (2021).

Abdullaev, N. A., Kakhramanov, S. S., Kerimova, T. G., Mustafayeva, K. M. & Nemov, S. A. Conductivity anisotropy in the doped Bi2Te3 single crystals. Semiconductors 43, 145–151 (2009).

Belen’kii, G., Abdullaev, N., Zverev, V. & Shteinshraiber, V. Y. Nature of the conductivity anisotropy and distinctive features in the localization of electrons in layered indium selenide. JETP Lett. 47, 584 (1988).

Fivaz, R. & Mooser, E. Mobility of charge carriers in semiconducting layer structures. Phys. Rev. 163, 743–755 (1967).

Carey, T. et al. High-mobility flexible transistors with low-temperature solution-processed tungsten dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 17, 2912–2922 (2023).

Lin, Z. et al. Solution-processable 2D semiconductors for high-performance large-area electronics. Nature 562, 254 (2018).

Cassidy, O. et al. Layer-by-layer assembly yields thin graphene films with near theoretical conductivity. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 9, 1–11 (2025).

Lin, Z. et al. High-yield exfoliation of 2D semiconductor monolayers and reassembly of organic/inorganic artificial superlattices. Chem 7, 1887–1902 (2021).

Tang, B. et al. Solution-processable 2D materials for monolithic 3D memory-sensing-computing platforms: opportunities and challenges. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 8, 74 (2024).

Rhee, D., Jariwala, D., Cho, J. H. & Kang, J. Solution-processed 2D van der Waals networks: fabrication strategies, properties, and scalable device applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 11, 021310 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. High-mobility patternable MoS2 percolating nanofilms. Nano Res. 14, 2255–2263 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Mechanistic insight into the chemical treatments of monolayer transition metal disulfides for photoluminescence enhancement. Nat. Commun. 12, 6044 (2021).

Rangnekar, S. V. et al. Electroluminescence from megasonically solution-processed MoS2 nanosheet films. ACS Nano 17, 17516–17526 (2023).

Kwak, I. C. et al. Orthogonal photopatterning of two-dimensional percolated network films for wafer-scale heterostructures. Nat. Electron. 8, 235–243 (2025).

Jones, L. A. H. et al. Band alignments, electronic structure, and core-level spectra of bulk molybdenum dichalcogenides (MoS2, MoSe2, and MoTe2). J. Phys. Chem. C. Nanomater Interfaces 126, 21022–21033 (2022).

Cunningham, G., Hanlon, D., McEvoy, N., Duesberg, G. S. & Coleman, J. N. Large variations in both dark- and photoconductivity in nanosheet networks as nanomaterial is varied from MoS2 to WTe2. Nanoscale 7, 198–208 (2014).

Das, P. K. et al. Layer-dependent quantum cooperation of electron and hole states in the anomalous semimetal WTe2. Nat. Commun. 7, 10847 (2016).

Chi, Z.-H. et al. Pressure-induced metallization of molybdenum disulfide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 036802 (2014).

Zhao, Z. et al. Pressure induced metallization with absence of structural transition in layered molybdenum diselenide. Nat. Commun. 6, 7312 (2015).

Nayak, A. P. et al. Pressure-induced semiconducting to metallic transition in multilayered molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 5, 3731 (2014).

Zhao, X.-M. et al. Pressure effect on the electronic, structural, and vibrational properties of layered 2H-MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 99, 024111 (2019).

Dunklin, J. R. et al. Production of monolayer-rich gold-decorated 2H–WS2 nanosheets by defect engineering. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 43 (2018).

Song, B. et al. In situ study of nucleation and growth dynamics of Au nanoparticles on MoS2 nanoflakes. Nanoscale 10, 15809–15818 (2018).

Kim, J., Byun, S., Smith, A. J., Yu, J. & Huang, J. Enhanced electrocatalytic properties of transition-metal dichalcogenides sheets by spontaneous gold nanoparticle decoration. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1227–1232 (2013).

Kuru, C. et al. MoS2 nanosheet–Pd nanoparticle composite for highly sensitive room temperature detection of hydrogen. Adv. Sci. 2, 1500004 (2015).

Ippolito, S. et al. Toposelective functionalization of solution-processed transition metal dichalcogenides with metal nanoparticles via defect engineering. Adv. Mater. 37, e06605 (2025).

Su, S. et al. Improving performance of MoS2-based electrochemical sensors by decorating noble metallic nanoparticles on the surface of MoS2 nanosheet. RSC Adv. 6, 76614–76620 (2016).

Shi, Y. et al. Selective decoration of Au nanoparticles on monolayer MoS2 single crystals. Sci. Rep. 3, 1839 (2013).

Kim, K. K. et al. Enhancing the conductivity of transparent graphene films via doping. Nanotechnology 21, 285205 (2010).

Chamlagain, B., Bhanu, U., Mou, S. & Khondaker, S. I. Tailoring the potential landscape and electrical properties of 2D MoS2 using gold nanostructures of different coverage density. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 6461–6466 (2020).

Pešić, J. et al. Imaging junctions in two-dimensional semiconductor nanosheet networks. npj 2D Mater. Appl 9, 90 (2025).

Rabaey, Jan. M. Digital integrated circuits: a design perspective. (Prentice Hall, 2002).

Cho, Y. et al. Influence of gas adsorption and gold nanoparticles on the electrical properties of CVD-grown MoS2 thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 21612–21617 (2016).

Ippolito, S. et al. Covalently interconnected transition metal dichalcogenide networks via defect engineering for high-performance electronic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 592–598 (2021).

Ricciardulli, A. G. et al. Defect-engineering of liquid-phase exfoliated 2D semiconductors: stepwise covalent growth of electronic lateral hetero-networks. Mater. Horiz. 11, 5614–5621 (2024).

Tang, B. et al. Wafer-scale solution-processed 2D material analog resistive memory array for memory-based computing. Nat. Commun. 13, 3037 (2022).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Single-molecule junctions of multinuclear organometallic wires: long-range carrier transport brought about by metal–metal interaction. Chem. Sci. 12, 4338–4344 (2021).

Liu, Y., Qiu, X., Soni, S. & Chiechi, R. C. Charge transport through molecular ensembles: recent progress in molecular electronics. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2, 021303 (2021).

Fujii, S. et al. Charge transport through single-molecule junctions with σ-delocalized systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 19566–19571 (2024).

Teixeira, C. et al. The origins and supply resilience of electronic nanomaterials in Europe. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6619913/v1 (2025).

Du, X. et al. Electronically weak coupled bilayer MoS2 at various twist angles via folding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 22819–22827 (2021).

Andrei, E. Y. et al. The marvels of moiré materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 201–206 (2021).

Seyler, K. L. et al. Signatures of moiré-trapped valley excitons in MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Nature 567, 66–70 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Correlated electronic phases in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 19, 861–866 (2020).

Liu, K. et al. Evolution of interlayer coupling in twisted molybdenum disulfide bilayers. Nat. Commun. 5, 4966 (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Effect of twist angle on interfacial thermal transport in two-dimensional bilayers. Nano Lett. 23, 7790–7796 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Zhan, Z., Guinea, F., Silva-Guillén, J. Á. & Yuan, S. Tuning band gaps in twisted bilayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 102, 4235418 (2018).

Yeh, P.-C. et al. Direct measurement of the tunable electronic structure of bilayer MoS2 by interlayer twist. Nano Lett. 16, 953–959 (2016).

Chari, T., Ribeiro-Palau, R., Dean, C. R. & Shepard, K. Resistivity of rotated graphite–graphene contacts. Nano Lett. 16, 4477–4482 (2016).

Liao, M. et al. Twist angle-dependent conductivities across MoS2/graphene heterojunctions. Nat. Commun. 9, 4068 (2018).

Matis, B. R., Garces, N. Y., Cleveland, E. R., Houston, B. H. & Baldwin, J. W. Electronic transport in bilayer MoS2 encapsulated in HfO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 27995–28001 (2017).

Shabani, S. et al. Deep moiré potentials in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Phys. 17, 720–725 (2021).

Ribeiro-Palau, R. et al. Twistable electronics with dynamically rotatable heterostructures. Science 361, 690–693 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Flat bands in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 16, 1093–1096 (2020).

Higgins, T. M. et al. Electrolyte-gated n-type transistors produced from aqueous inks of WS2 nanosheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1804387 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Ghawri, B. et al. Electronic confinement induced quantum dot behavior in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nanoscale 17, 4030–4037 (2025).

Huang, S., Yankowitz, M., Chattrakun, K., Sandhu, A. & LeRoy, B. J. Evolution of the electronic band structure of twisted bilayer graphene upon doping. Sci. Rep. 7, 7611 (2017).

Melchakova, I. A., Oyeniyi, G. T., Polyutov, S. P. & Avramov, P. V. Spin polarization and flat bands in eu-doped nanoporous and twisted bilayer graphenes. Micromachines 14, 1889 (2023).

Acknowledgements

A.G.K. acknowledges funding from the European Commission through a Marie Skłodowska–Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship “NanoHarvest” (proposal number: 101107032) and national funds from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I. P., in the scope of the projects LA/P/0037/2020, UIDP/50025/2020 and UIDB/50025/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute of Nanostructures, Nanomodelling and Nanofabrication – i3N. A.G.K. would like to thank professor Cory R. Dean for his clarifications on carrier behaviour in moiré systems and Dr. Cian Gabbett for the SEM image in Figs. 1 and 5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.K. is the sole author of this Perspective.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, A.G. Junction engineering in solution-processed nanosheet networks. npj 2D Mater Appl 10, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00647-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00647-0