Abstract

Many life-saving drugs are derived from fungal secondary metabolites, and the rich diversity of these metabolites is a gold mine of bioactive compounds for drug discovery. However, the biosynthetic genes for most secondary metabolites remain transcriptionally silent in fungi, posing a significant bottleneck in their discovery. Here, we apply a systematic approach to separately over-express 51 secondary metabolism-related transcription factors using the strong inducible promoter of the xylP gene from Penicillium chrysogenum. Growing the individual secondary metabolism transcription factor over-expression strains under inducible conditions leads to the production of a collection of diverse metabolites with anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and anti-cancer activities. The overall approach and the over-expression system established in this study are broadly-applicable, providing a valuable means to revealing the pharmaceutical potentials of fungi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungal secondary metabolites represent a rich repertoire of natural products1,2. Although numerous secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) have been identified bioinformatically in thousands of fungal genomes, the functionality of these predicted BGCs and their potential to produce metabolites awaits validation. More importantly, most BGCs remain transcriptionally silent under standard laboratory conditions. The transcriptional silencing is believed to be due to epigenetic regulation and/or regulation of BGC-specific transcription factors (TFs)2,3,4, which are defined merely based on the physical location of their genes within a BGC. Consequently, the vast majority of fungal secondary metabolites have not been identified, and their bioactivity remains unknown. Despite the development of various methods and significant efforts to explore this rich resource2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, most studies have been limited to a low-throughput approach—activating one cluster at a time to induce the production of its secondary metabolite, which is then tested for bioactivity10,12,13,14. Notably, a recent study has systematically over-expressed 58 BGC-specific transcription factors of Aspergillus niger, leading to the production of potentially novel compounds15. Although the bioactivity of those compounds was not determined in that study, such systematic approach provides a valuable means to evaluate the pharmaceutical potential of a given fungus for drug discovery.

In the well-studied filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans, 71 secondary metabolite BGCs had been identified from its genome sequence bioinformatically more than a decade ago16. However, to date, more than half of them are still uncharacterized and their pharmaceutical potentials unknown. In a previous study, 33 BGC-specific TFs from 17 predicted secondary metabolite BGCs of A. nidulans were systematically over-expressed using the ethanol-inducible alcA promoter17. Contrary to previous successes with this over-expression (OE) strategy18,19, only three secondary metabolite BGCs were activated to produce detectable levels of their compounds. This leaves an impression that the secondary metabolism (SM) TF OE strategy may not be universally applicable for all clusters. Consequently, the straightforward strategy has not been exploited for systematic screening of bioactive metabolites. Here, we systematically over-express 51 secondary metabolism related TFs in A. nidulans using a strong inducible promoter and demonstrated the power of the systematic TF OE approach for drug discovery.

Results and discussion

Expression of SM TF from a strong promoter facilitates secondary metabolite BGC gene activation

Upon examining the experimental setup of the previous A. nidulans study17 and comparing with the recent A. niger study15, a potential explanation for the low success rate emerged. The alcA promoter used in the A. nidulans study17 may not sufficiently elevate the transcriptional levels of most BGC-specific TF genes at their native genomic locus, which is believed to be regulated by repressive chromatin20,21. In addition, those TFs may be negatively controlled post-transcriptionally.

We hypothesized that most of secondary metabolite cluster genes would be induced if their cluster-specific TFs are sufficiently over-expressed (i.e. expressed at a level higher than that by the alcA promoter) and, therefore, undertook a similar systematic approach with slight modifications. First, we selected the xylP promoter from Penicillium chrysogenum, which is tunable and stronger than the alcA promoter and other commonly used promoters (e.g., pcbC and niaD), for conditional induction22,23,24. Second, we targeted the TF OE construct to the yA gene locus, which is supposedly not suppressed by repressive chromatin structures.

To test the feasibility of this strategy, the SM TF AN6790, which was over-expressed in the previous study17 but failed to induce cluster activation (i.e., no novel product was detected in the alcA(p)::AN6790 strain after induction), and AflR (the best-studied cluster-specific activator of the biosynthetic genes for sterigmatocystin) were used as proof-of-principle examples. While both AN6790 and AflR proteins could not be detected under normal control conditions (i.e. without xylose), their levels were significantly induced in the presence of xylose (Fig. 1a), confirming their conditional expression.

a Western blot analysis of AflRHA (MW = 51.3 kD) and AN6790FLAG (MW = 71.7 kD) in the respective over-expression (OE) strains grown in the presence (+) and absence (-) of the xylose inducer. The expected protein size is indicated; b Images of fermentation broth (top panel) and their EtoAc extracts (bottom panel) of the indicated over-expression strains grown with 1% xylose induction; c, d LC-MS profiles of the EtoAc extract from the wild-type and AflR over-expression strains with 1% xylose induction; e Images of fermentation broth (top panel) and their ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts (bottom panel) of the indicated over-expression strains grown with 1% xylose induction.

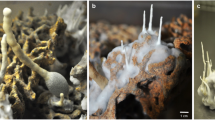

To determine if the over-expression could successfully induce SM production and to compare with the previous studies15,17, we used liquid culture conditions to analyze and compare metabolites production. The wild-type, AN6790-OE and AflR-OE strains were grown in ANM medium for 48 h at 37 °C, followed by addition of 1% xylose, and cultured for an additional three days. After five days of culture, the wild-type strain produced mauve pigment, while the AN6790-OE and AflR-OE strains produced orange and yellow pigments, respectively (Fig. 1b). Given that many fungal metabolites are pigmented25, these color differences in the media of the different OE strains suggest the production of diverse metabolites by the OE strains. Indeed, LC-MS analysis of the growth media from the AflR-OE strain confirmed the production of sterigmatocystin (ST) (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, a unique metabolite profile was also observed for the AN6790-OE strain comparing to the wild type (WT) (Fig. 1d). Therefore, the revised OE setup can successfully activate SM gene expression and production from cryptic secondary metabolite BGCs.

Systematic overexpression of transcription factors implicated in secondary metabolism leads to production of diverse metabolites

To further demonstrate the valuable potential of the strategy, we set out to systematically activate secondary metabolite BGCs in A. nidulans to screen for novel metabolites with pharmaceutical properties. TFs with potential roles in SM regulation were selected using several approaches. First, TFs located within predicted secondary metabolite BGCs annotated by SMURF (Secondary Metabolite Unknown Regions Finder) (http://www.jcvi.org/smurf/index.php)26 or clusters identified in previous publications were considered candidates16,27. This included 33 uncharacterized (Table 1) and nine known TFs (aflR, afoA, apdR, atnN, dbaA, mdpA, mdpE, pbcR and scpR). Additionally, TF genes outside of the annotated secondary metabolite BGCs but previously associated with SM regulation based on publications (rsmA, napA, mtfA, and hapX) and information from the AspGD database (AN2025, AN2026, AN2241, AN4933 and AN8645) were also included. In total, 51 TFs (see Table 1 for details) were selected. These TFs are lowly- or non-expressed under most experimental conditions based on expression analysis of 878 public RNAseq data (Supplementary Fig. 1)28, and their lack of expression is presumably the main reason for the silencing of SM clusters.

Building on the success of the AflR-OE and AN6790-OE strains described above, and in anticipation of scaling up for secondary metabolite purification, the same liquid culture setup was applied to the OE strains. When the expression of SM TFs was induced with xylose, the culture media of many strains exhibited diverse pigmentation distinct from the wild-type strain (Fig. 1e). The colors ranged from dark purple/red (e.g., RsmA and DbaA) to brown (e.g., AN2025, AN3269, AN8391, and AN5609) to light yellow (e.g., AflR, AN3501, AN8645, AN2241, AN3391, ApdR, AN10295, AN0533, AN4837, AtnN, and AN8506). Notably, some pigments were secreted into the broth, while others were contained within the mycelial mass (Fig. 1e). For example, the broth of fourteen OE strains (AN4933, NapA, AN7923, AN8902, AN7061, AN8509, AN9013, AN0153, AN1678, MtfA, AN3502, AfoA, AN7921, and AN10294) showed similar coloration to the WT, while their mycelia exhibited different colors. Lastly, a group of OE strains produced similar colors in both the mycelia and the culture media as the wild-type strain. Considering that many fungal metabolites are pigmented29, these observations indicate the production of diverse metabolites by these strains and the success of the SM TF OE strategy.

The collection of metabolites contains anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and anti-cancer activities

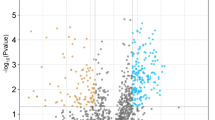

To determine the pharmaceutical potential of A. nidulans, crude extracts of secreted metabolites from the SM TF OE strains were assayed for various bioactivities. The use of crude extracts allows identification of bioactivities from intermediate metabolites and byproducts rather than just the final product of a given secondary metabolite BGC. For antibacterial activities, the extracts were tested against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, representing non-pathogenic and pathogenic bacteria, respectively. Growth was measured by absorbance at OD600 nm and compared between metabolites extracted from the culture media of wild-type and OE strains grown in the presence of 1% xylose. Remarkably, more than half of the SM TF OE strains produced metabolites with varying degrees of anti-bacterial activity against B. subtilis and/or S. aureus (Fig. 2a). One extract (AN3911) initially promoted bacterial growth between 4 and 10 h post-inoculation, but this effect diminished over time. Notably, the extracts of eight strains (DbaA, AN6790, AN3501, AN4933, AN7921, RsmA, AN7061, and AN2025) inhibited the growth of both B. subtilis and S. aureus by over 50% compared to the control, with the extract from the DbaA-OE strain exhibiting the most potent activity, achieving nearly 90% inhibition. This result aligns with previous findings that DbaA OE leads to the production of the antibiotic 2,4-dihydroxy-3-methyl-6-(2-oxopropyl)benzaldehyde (DHMBA)30,31, validating our approach for identifying bioactive metabolites and highlighting the anti-bacterial potential of metabolites produced by the other seven OE strains.

A heatmap displaying the results of (a) B. subtilis, S. aureus (b) C. albicans growth assay in the presence and absence of EtOAc extracts from wild-type and the indicated over-expression strains. Each box displays the average OD600 difference of B. subtilis, S. aureus or C. albicans incubated with the extract of OE strains relative to that of WT at indicated time points (Tables 2 and 3). The presented result is an average of two biological repeats; c Bar charts showing the survival of murine fibroblast (L929), human colon cancer (HCT116), Alexander hepatoma carcinoma (PLC5), and Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (C666.1) cell lines. The mean of at least two biological repeats for each extract is shown, with the values of repeats depicted by red dots. Extract with less inhibition on the control cell line (L929) than on at least one cancer cell line was highlighted by a red box.

Some fungal secondary metabolites possess anti-fungal properties that can be exploited for anti-fungal treatments, such as griseofulvin produced by Penicillium griseofulvum31.To this end, an anti-fungal bioactivity assay was performed using the same extracts on the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans to identify anti-fungal properties. Only two extracts (from DbaA and AN7061 strains) produced a strong inhibitory effect (ΔOD600[WT-OE] >0.5) on C. albicans growth (Fig. 2b), while the extract of the AN3911-OE strain, which had a positive effect on bacterial growth, also weakly promoted C. albicans growth. Interestingly, many extracts displayed mild (ΔOD600[WT-OE] <0.5) but significant anti-fungal activities with stage-specific patterns. For example, a group of extracts inhibited the early growth of C. albicans (~2–10 h post-inoculation), while other groups affected later stages (e.g., 6–24 h and 16–24 h). The biological significance of these stage-specific activities is currently unclear. Overall, there are less metabolites with anti-fungal activities comparing to anti-bacterial activities.

A high-throughput screen was also performed to identify anti-cancer activity. Cell lines representing three different cancer types (HCT116 colon cancer cells, PLC5 hepatoma cells, and C666.1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells) were tested, with the murine fibroblast cell line, L929, as the normal cell control. High content imaging analysis shows that the extracts exhibited differential inhibitory effects on mammalian cells (Fig. 2c). For HCT116 colon cancer cells, six extracts (from AN10300, DbaA, AN2025, AN3501, RsmA, and ScpR OE strains) demonstrated strong growth inhibition, resulting in a survival rate of less than 50% when treated with these extracts (Fig. 2c). For the hepatoma PLC5 cell line, treatment with extracts from five OE strains (AN3911, DbaA, AN3501, RsmA, and ScpR) led to a survival rate of less than 50% (Fig. 2c). For the C666.1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line, eight extracts (from ApdR, AN10300, AN10295, DbaA, AN7921, AN3501, RsmA, and ScpR OE strains) displayed significant inhibition (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the extract from the AN3911-OE strain, which positively affects bacterial and fungal growth, significantly inhibited the proliferation of PLC5 and C666.1 cells but not HCT116 cells. Overall, six, five, and eight extracts showed potent anti-cancer activity against HCT116, PLC5, and C666.1 cancer cells, respectively, with three extracts (from AN3501, RsmA, and ScpR OE strains) inhibiting all three cancer cell lines. Among these extracts, a few (ones from the AN3501, RsmA, and AN10295 OE strains) were cytotoxic based on their effects on the normal fibroblast L929 cell line. The remaining six extracts (from AN10300, AN2025, AN3911, DbaA, ApdR, and ScpR OE strains) exhibited different levels of specificity against cancer cells (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Data 1), indicating their potential for anti-cancer drug development.

Potential limitations, considerations and conclusions

Taken together, this study highlights the power of systematically activating BGCs in fungi to identify potential bioactive metabolites. Although our revised strategy—employing a stronger promoter and integration at the yA genomic locus—has proven successful for many BGCs, it does have some limitations. First, eukaryotic gene activation, and SM gene regulation in particular, is often subject to combinatorial control. This regulation requires multiple elements, including global TFs, chromatin-modifying proteins, mediators32,33,34 and post-translational modifications. Our strategy of single TF OE does not account for this complex coordination and, therefore, could not activate all BGCs, which was elegantly demonstrated by the transcriptome analysis in the recent systematic SM TF OE study of A. niger15. A similar transcriptome analysis on our SM TF OE strains would help determine how many of the BGCs analyzed in this study could not be activated. Second, our approach primarily targets TFs located within annotated BGCs. As a result, metabolites produced by BGCs lacking a TF35,36 or by non-clustered biosynthetic genes10,37 may be overlooked. Third, excessive TF expression can lead to off-target activation, resulting in the production of non-specific metabolites and/or altered fungal physiology. While this may complicate the identification of primary BGC-derived metabolites, it could also be advantageous if these non-specific metabolites—typically not produced under normal conditions—exhibit useful bioactivities.

While the systematic TF OE strategy has demonstrated efficacy in A. nidulans, its broader application to non-model or genetically intractable fungi requires several important considerations. A key prerequisite is the availability of well-characterized genetic tools, including strong inducible promoters, efficient transformation systems, and reliable selection markers—resources often lacking in less-studied fungal species. Moreover, targeted genomic integration, which we achieved at the yA locus, may be inefficient or unpredictable in species with low homologous recombination efficiency or without an effective targeting system (e.g., nkuA∆ equivalent strains38). At the transcriptional level, BGCs in some fungi may reside in heterochromatic regions, where silencing mechanisms differ from those in A. nidulans39, making TF overexpression alone insufficient to overcome repression. Additionally, promoter activity can be context-dependent. Even strong promoters like xylP may not function optimally under all conditions40 or in other fungal species, presumably due to differences in transcriptional machinery or regulatory networks.

Despite these challenges, advances in synthetic biology and gene editing technologies—such as CRISPR-Cas—have made genome engineering increasingly feasible in fungi. Therefore, the SM TF OE strategy presented in this work offers a powerful approach for uncovering the pharmaceutical potential of diverse fungal species.

Methods

Strains construction

The xylose-inducible promoter xylP(p) from P. chrysogenum23 was selected for conditional expression of SM TFs. To allow detection of SMTFs, epitope tags such as 3×HA, 3×FLAG, or 6×HIS were also added to the C-terminus of each SMTF of interest41. To create the OE constructs, a starting plasmid (XPyA-3, CWB13) carrying the xylP promoter, a 724 bp internal fragment of the yA gene for targeted integration42, and the Aspergillus fumigatus pyroA gene as the selection marker43, was linearized by SmaI (NEB, cat no. R0141) digestion. Fragments containing epitope tag, 3×HA or 3×FLAG, or 6×HIS and ADH1(t) were then amplified from the established tagging plasmids using the TF gene-specific primer OE-F and ADH1(t)_R (1716) (CTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCCCCCGGTAGAGGTGTGGTC), and after PCR purification, fused with the prepared linear XPyA-3 vector by isothermal assembly. In this way, a set of new starting plasmids containing different epitope tags was created, from which a linear vector (XPyA-3-1) carrying xylP promoter, 3×HA and the terminator ADH1(t) was amplified by inverse PCR using oligo pks_reverse_R (2661) and longtin F (3789). To create target gene OE plasmid, a fragment starting from the 10 bp upstream of start codon ATG to the base exactly before the stop codon of target gene was amplified from genomic DNA of the A. nidulans MH11036 strain and fused with XPyA-3-1, which efficiently resulted in production of an OE plasmids library composed of genes-of-interest fusing with 3×HA epitope tags (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Likewise, OE plasmids for target genes with other epitope tags, 3×FLAG and 6×HIS, were also created. The plasmids were confirmed by sequencing and transformed into the MH11036 (veA1, nkuA∆, pyroA4, riboB2) strain. Transformation was carried out using the protoplast method44. The OE constructs carry a 724 bp internal fragment of the yA gene and the A. fumigatus pyroA gene for targeted integration24 and selection, respectively. If the OE plasmid integrated at the yA locus, the transformants would have the yA gene disrupted, leading to yellow conidia (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Therefore, transformants with yellow conidia were selected on solid minimal medium lacking pyridoxine. Southern blot analysis was applied to confirm integration at yA, determine the construct copy-number integrated into the genome, and rule out any ectopic integration that might have happened other than at the yA locus (Supplementary Fig. 3). Transformants with only a single integrated plasmid copy were selected for further study.

Growth conditions

Aspergillus nidulans minimal (ANM) media was used for standard growth45. For SM TF OE, 5 × 105 mL−1 spores of SM TF OE strains and their wild-type recipient strain (pyroA4, riboB2, and nkuA∆) were grown in 100 mL liquid ANM medium supplemented with pyridoxine (0.5 mg L−1) (Sigma, cat. no. P9755) and riboflavin (2.5 mg L−1) (Sigma, cat. no. R7649) at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. After 48 h, xylose was added with a final concentration being 1% and strains were grown for an additional three days.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted using the TCA method46 and quantified using BioRAD DC Protein Assay (BIO-RAD, cat. no. 5000112). 50 μg total protein was loaded in SDS-PAGE gel for each sample. The transformation of the protein in gel to PVDF membrane (BIO-RAD, cat. no. 1620177) were performed by wet-transfer overnight at 40 V. With respect to primary antibody, the dilution is 1:3000 for HA-Tagged protein (Santa Cruz, cat. no. sc7392), 1:5000 for FLAG-tagged protein (Monoclonal ANTI-FLAG® M2, Sigma, cat. no. F3165), 1:5000 for HIS-tagged protein (Abcam, ab9108) and 1:10000 for H3 (Abcam, ab1791). 1:5000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (Sigma-Aldrich, AP124P) or anti-rabbit antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, AP132P) were used based on the primary antibody type. The ClarityTM ECL substrate kit (BIO-RAD, cat. no. 1705060) was applied for chemiluminescence detection. The uncropped Western Blot images of Fig. 1a are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Metabolites extraction

Culture media was collected by filtering using a clean cheesecloth to remove mycelia and extracted twice with equal volume of EtOAc. The ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extracts were dried by rotary evaporator (EYELA, Japan) at 25 °C. The residues were resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (ChemCruz, cat. no. SC-358801) to bring the concentration to 10 mg mL−1.

LC-MS analysis

LC-MS was performed using the ion trap mass spectrometer in positive ion mode with a BEH C18 Column, 130 Å, 1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm (Waters, USA), as described in the previous study40. Each sample with a concentration of 10 mg mL−1 was diluted tenfold with methanol and loaded in triplicates. Waters Masslynx V4.1 workstation software and the program MestReNova (Version 14.1.0, MestReC, Spain) was used to process the LC-MS data.

Anti-bacterial assay

To detect the antibacterial activity of EtOAc extracts from each OE strain, the gram-positive bacteria S. aureus (ATCC 25904) and B. subtilis (ATCC 21336) were used. Bacterial cells were grown in liquid LB medium in a microtitre plate. Extracts of OE strains were added at a final concentration of 50 µg mL−1. The optical density of bacteria at λ = 600 nm (OD600) was measured at 15 min intervals over a 24 h period using a Cytation 3 microplate reader. Each extract was tested against each bacterial species three times and repeated twice independently (i.e. a total of six measurements). The differences in the OD600 values of the test bacteria incubated with extracts from WT and each OE strain were presented as a heatmap (Fig. 2b).

Anti-fungal assay

To test the antifungal activity of these EtOAc extracts, C. albicans (SC5314) was used as the test strain. It is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast that poses a threat to immunocompromised individuals. The screening test was performed in a microplate assay and 5 µL diluted EtOAc extracts were added to 195 µL diluted C. albicans (OD600 = 0.01) at logarithmic phase to give a final concentration of 50 µg mL−1. The OD600 of C. albicans during the 24 h growth period was measured at 15 min intervals. The test for each EtOAc extract against each strain was performed in triplicate and repeated twice independently (i.e. six measurements in total). The difference in the OD600 of C. albicans culture incubated with EtOAc extracts from WT and each OE strain was visualized as a heatmap (Fig. 2c).

Anti-cancer cell assay

Cell viability screening was conducted on the EtOAc extracts using L929, HCT116, PLC5, and C666.1 cell lines, which were routinely subjected to mycoplasma testing using the mycoplasma detection kit from TransGen Biotech (FM311-01). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at the following densities: L929 (1.5 × 104), HCT116 (2.5 × 104), PLC5 (1.0 × 104), and C666.1 (4.0 × 104). L929, HCT116, and PLC5 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, cat. no. 12100046) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, cat. no. 10270106), while C666.1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with GlutaMAX (Gibco, cat. no. 61870036) and 10% FBS. For the treatment of L929 and HCT116 cells, extracts were applied at a final concentration of 3 µg mL−1 for 24 h. For PLC5 and C666.1 cells, extracts were used at a final concentration of 1.5 µg mL−1 for 48 h. All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After treatment, the cells were stained with the LIVE/DEADTM Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen, cat. no. L3224) and Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, cat. no. H3570), then imaged using the PerkinElmer Opera Phenix High Content Screening System in confocal mode with a 20×water objective (NA 1.0). The fluorophores were detected using the following excitation and emission (Ex/Em) wavelengths: Hoechst 33342 (405/435–480), calcein-AM (488/500–550), and ethidium homodimer-1 (561/570–630). Image analysis was conducted using PerkinElmer Harmony Software.

Statistics and reproducibility

For the same TF OE strain, two biological replicates were performed on two different days for EtoAc extract preparation. Anti-bacterial assay against B. subtilis and S. aureus, and anti-fungal assay against C. albicans were performed with two biological replicates, each with three technical replicates. In the anti-cancer cell assay, a minimum of two biological replicates were analyzed, with nine selected strains subjected to four replicates (see Supplementary Data 1). For statistical analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3, two-tailed student t-test was employed to compare each OE strain with the WT cultured in ANM medium. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, very significant at p < 0.01, and extremely significant at p < 0.001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study have been included in the supplementary files. Source data can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and the original Western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The plasmids and strains will be made available on request. Please contact the corresponding authors at koonhowong@um.edu.mo and guosh@wxu.edu.cn.

References

Bills, G. F. & Gloer, J. B. Biologically active secondary metabolites from the fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 4 (2016).

Keller, N. P. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 167–180 (2019).

Brakhage, A. A. & Schroeckh, V. Fungal secondary metabolites - strategies to activate silent gene clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48, 15–22 (2011).

Brakhage, A. A. Regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 21–32 (2013).

Netzker, T. et al. Microbial communication leading to the activation of silent fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Front. Microbiol. 6, 299 (2015).

Fischer, J., Schroeckh, V. & Brakhage, A. A. Awakening of fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Gene expression systems in fungi: advancements and applications, 253-273 (2016).

Roux, I. et al. CRISPR-mediated activation of biosynthetic gene clusters for bioactive molecule discovery in filamentous fungi. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 1843–1854 (2020).

Chiang, C.-Y., Ohashi, M. & Tang, Y. Deciphering chemical logic of fungal natural product biosynthesis through heterologous expression and genome mining. Nat. Prod. Rep. 40, 89–127 (2023).

Woodcraft, C., Chooi, Y. H. & Roux, I. The expanding CRISPR toolbox for natural product discovery and engineering in filamentous fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 40, 158–173 (2023).

Rabot, C. et al. Transcription factor engineering in Aspergillus nidulans leads to the discovery of an orsellinaldehyde derivative produced via an unlinked polyketide synthase gene. J. Nat. Prod. 87, 2384–2392 (2024).

Wang, M., Chen, L., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Q. Recent advances in genome mining and synthetic biology for discovery and biosynthesis of natural products. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 45, 236–256 (2025).

Ninomiya, A., Urayama, S. I. & Hagiwara, D. Antibacterial diphenyl ether production induced by co-culture of Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 4169–4185 (2022).

Darma, R. et al. Transcriptomics-Driven Discovery of New Meroterpenoid Rhynchospenes Involved in the Virulence of the Barley Pathogen Rhynchosporium commune. ACS Chem. Biol. 20, 421–431 (2025).

Shang, Z. et al. Self-Resistance Gene-Guided Discovery of the Molecular Basis for Biosynthesis of the Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibitor Cerulenin. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 64, e202414941 (2025).

Semper, C. et al. Global survey of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus niger via activation of specific transcription factors. bioRxiv, 2024.2007. 2018.604165 (2024).

Inglis, D. O. et al. Comprehensive annotation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes and gene clusters of Aspergillus nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. niger and A. oryzae. BMC Microbiol 13, 91 (2013).

Ahuja, M. et al. Illuminating the diversity of aromatic polyketide synthases in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8212–8221 (2012).

Bergmann, S. et al. Genomics-driven discovery of PKS-NRPS hybrid metabolites from Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 213–217 (2007).

Chiang, Y. M. et al. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans monodictyphenone gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 2067–2074 (2010).

Gacek, A. & Strauss, J. The chromatin code of fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 95, 1389–1404 (2012).

Reyes-Dominguez, Y. et al. Heterochromatic marks are associated with the repression of secondary metabolism clusters in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1376–1386 (2010).

Marx, F. et al. Proper folding of the antifungal protein PAF is required for optimal activity. Res Microbiol. 156, 35–46 (2005).

Zadra, I., Abt, B., Parson, W. & Haas, H. xylP promoter-based expression system and its use for antisense downregulation of the Penicillium chrysogenum nitrogen regulator NRE. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 4810–4816 (2000).

Wong, K. H., Hynes, M. J., Todd, R. B. & Davis, M. A. Transcriptional control of nmrA by the bZIP transcription factor MeaB reveals a new level of nitrogen regulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 534–551 (2007).

Narsing Rao, M. P., Xiao, M. & Li, W. J. Fungal and bacterial pigments: secondary metabolites with wide applications. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1113 (2017).

Khaldi, N. et al. SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 736–741 (2010).

Yin, W. & Keller, N. P. Transcriptional regulatory elements in fungal secondary metabolism. J. Microbiol. 49, 329–339 (2011).

Parsania, C. et al. FungiExpresZ: an intuitive package for fungal gene expression data analysis, visualization and discovery. Brief Bioinform. 24, bbad051 (2023).

Caro, Y., Venkatachalam, M., Lebeau, J., Fouillaud, M. & Dufossé, L. Pigments and colorants from filamentous fungi. Fungal Metabolites, 499-568 (Springer, 2017).

Gerke, J. et al. Breaking the silence: protein stabilization uncovers silenced biosynthetic gene clusters in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 8234–8244 (2012).

Oxford, A. E., Raistrick, H. & Simonart, P. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms: Griseofulvin, C(17)H(17)O(6)Cl, a metabolic product of Penicillium griseo-fulvum Dierckx. Biochem. J. 33, 240–248 (1939).

Lim, F. Y., Sanchez, J. F., Wang, C. C. & Keller, N. P. Toward awakening cryptic secondary metabolite gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Methods Enzymol. 517, 303–324 (2012).

Eagan, J. L. & Keller, N. P. Fungal secondary metabolism. Curr. Biol. 35, R503–R508 (2025).

de Boer, C. G. et al. Deciphering eukaryotic gene-regulatory logic with 100 million random promoters. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 56–65 (2020).

Bouhired, S., Weber, M., Kempf-Sontag, A., Keller, N. P. & Hoffmeister, D. Accurate prediction of the Aspergillus nidulans terrequinone gene cluster boundaries using the transcriptional regulator LaeA. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 1134–1145 (2007).

Sprote, P. et al. Identification of the novel penicillin biosynthesis gene aatB of Aspergillus nidulans and its putative evolutionary relationship to this fungal secondary metabolism gene cluster. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 445–461 (2008).

Kwon, M. J. et al. Beyond the biosynthetic gene cluster paradigm: genome-wide coexpression networks connect clustered and unclustered transcription factors to secondary metabolic pathways. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e0089821 (2021).

Nayak, T. et al. A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 172, 1557–1566 (2006).

Galazka, J. M. & Freitag, M. Variability of chromosome structure in pathogenic fungi-of ‘ends and odds’. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 20, 19–26 (2014).

Wang, F. et al. Transcription in fungal conidia before dormancy produces phenotypically variable conidia that maximize survival in different environments. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1066–1081 (2021).

Qin, L. et al. Universal plasmids to facilitate gene deletion and gene tagging in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 125, 28–35 (2019).

Wong, K. H. et al. Sumoylation in Aspergillus nidulans: sumO inactivation, overexpression and live-cell imaging. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45, 728–737 (2008).

Osmani, A. H., May, G. S. & Osmani, S. A. The extremely conserved pyroA gene of Aspergillus nidulans is required for pyridoxine synthesis and is required indirectly for resistance to photosensitizers. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 23565–23569 (1999).

Andrianopoulos, A. & Hynes, M. J. Cloning and analysis of the positively acting regulatory gene amdR from Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 3532–3541 (1988).

Cove, D. J. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113, 51–56 (1966).

Todd, R. B., Fraser, J. A., Wong, K. H., Davis, M. A. & Hynes, M. J. Nuclear accumulation of the GATA factor AreA in response to complete nitrogen starvation by regulation of nuclear export. Eukaryot. Cell 4, 1646–1653 (2005).

Bok, J. W. et al. Chromatin-level regulation of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 462–464 (2009).

Chiang, Y. M. et al. A gene cluster containing two fungal polyketide synthases encodes the biosynthetic pathway for a polyketide, asperfuranone, in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2965–2970 (2009).

Bromann, K. et al. Identification and characterization of a novel diterpene gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 7, e35450 (2012).

Bergmann, S. et al. Activation of a silent fungal polyketide biosynthesis pathway through regulatory cross talk with a cryptic nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 8143–8149 (2010).

Shaaban, M. I., Bok, J. W., Lauer, C. & Keller, N. P. Suppressor mutagenesis identifies a velvet complex remediator of Aspergillus nidulans secondary metabolism. Eukaryot. Cell 9, 1816–1824 (2010).

Asano, Y., Hagiwara, D., Yamashino, T. & Mizuno, T. Characterization of the bZip-type transcription factor NapA with reference to oxidative stress response in Aspergillus nidulans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 1800–1803 (2007).

Yu, J. H. et al. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr. Genet. 29, 549–555 (1996).

Andersen, M. R. et al. Accurate prediction of secondary metabolite gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E99–E107 (2013).

Tanaka, A., Kato, M., Nagase, T., Kobayashi, T. & Tsukagoshi, N. Isolation of genes encoding novel transcription factors which interact with the Hap complex from Aspergillus species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1576, 176–182 (2002).

Ramamoorthy, V. et al. The putative C2H2 transcription factor MtfA is a novel regulator of secondary metabolism and morphogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One 8, e74122 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Wong laboratory for their valuable comments and discussions, and Prof. Yit-Heng Chooi and Prof. Zhou (Alex) Shang for their advice and suggestions. We acknowledge the services and technical support provided by the Genomics and Single Cell Analysis Core, as well as the Drug and Development Core of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Macau. This work was partially conducted on the High-Performance Computing Cluster (HPC), supported by the Information and Communication Technology Office (ICTO) of the University of Macau. We gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macao S.A.R. (FDCT, project no. 0099/2022/A2), the Research Services and Knowledge Transfer Office (project nos. MYRG2022-00107-FHS and MYRG-GRG2023-00084-FHS-UMDF), and the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, awarded to K.H.W. and Research Grants Council, HK. (C5012-15E) to B.C.B.K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. and K.H.W. conceived the study, designed experiments, and interpreted data. S.G., L.Q., C.Y.C., L.F. and C.C.M. performed experiments. S.G., L.P., C.P. and X.L. performed Bioinformatics analysis. K.T. and Z.D. provided technical support. K.H.W., K.T. and B.C.B.K. provided funding. S.G. and K.H.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. K.H.W. is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Biology, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Pardeshi, L., Qin, L. et al. Systematic over-expression of secondary metabolism transcription factors to reveal the pharmaceutical potential of Aspergillus nidulans. Commun Biol 8, 1444 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08840-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08840-z