Abstract

The Meissner effect is a hallmark of superconductivity arising from the interplay between charged superfluids and electromagnetic fields. However, superfluidity can also occur in systems of charge-neutral particles with magnetic or electric dipole moments, such as Bose-Einstein condensates of magnons or excitons. Despite this interest, the electromagnetic response of dipole superfluids, including potential analogues or contrasts to the Meissner effect, remains poorly understood. Here we develop a Ginzburg-Landau theory to describe dipole superfluids subjected to a pseudo-magnetic field, which is induced by a spatially modulating electromagnetic field. In magnetic dipole superfluids, the response differs strikingly from the conventional Meissner effect: the external field is enhanced by a positive feedback, forming a vortex lattice separated by singular domain walls with diverging electric charges. In contrast, electric dipole superfluids exhibit screening akin to superconductors, where the pseudo-magnetic field is suppressed except near vortices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When a magnetic field is applied to a superconductor, an electric supercurrent flows to expel the external magnetic field, a phenomenon known as the Meissner effect. This arises from a unique interaction between the condensate of charged particles and the electromagnetic field. However, condensates can also form from particles with different electromagnetic properties. Of particular interest is a superfluid composed of charge-neutral particles that possess a magnetic dipole moment. Recent attention has focused on such systems, including spin-triplet excitonic insulators1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 and magnon Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs)11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27.

In general, magnetic dipoles experience a geometrical phase known as the Aharonov-Casher (AC) phase28, analogous to the Aharonov-Bohm (AB) phase observed for charged particles in magnetic fields. In the AC effect, an electric field acts as an effective vector potential, and hence spatial variations in the electric field generate a pseudo-magnetic field29,30,31,32,33, which plays a role analogous to the real magnetic field in the AB effect. The AC effect has been observed in a wide range of systems, including neutrons34, atomic systems35, mesoscopic systems36,37,38,39,40,41, Josephson vortices42,43,44, and spin waves45,46. In particular, the AC effect serves as a fundamental basis for spin-current-driven electric polarization, enabling multiferroicity in magnetic materials47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56.

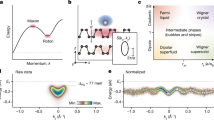

This raises a natural question: When magnetic dipoles condense into a superfluid, how do they respond to a pseudo-magnetic field (a spatially varying electric field) induced by the AC effect? The interaction between magnetic-dipole superfluids and the AC phase has been explored from various theoretical perspectives57,58,59,60,61,62. In this work, we propose a Ginzburg-Landau phenomenological theory to describe dipole superfluids in external electromagnetic fields, revealing behavior that starkly contrasts with that of superconductors. We find that, under a pseudo-magnetic field, a dipole superfluid spontaneously forms a vortex lattice similar to a type-II superconductor, though the field texture is nearly the inverse of what is observed in conventional type-II superconductors. Figure 1 compares the vortex lattices in (a) a type-II superconductor (electric-monopole superfluid) under a magnetic field and (b) a magnetic-dipole superfluid under a pseudo-magnetic field, which constitutes the main result of this work. In each figure, the left panel illustrates the distribution of the supercurrent, and the right panel depicts the distribution of the real magnetic field in (a) and the pseudo-magnetic field in (b). In the superconductor [Fig. 1(a)], the supercurrent circulates only in the vicinity of the vortices, where the magnetic field is concentrated. In contrast, in the magnetic-dipole superfluid, the circulation of the supercurrent extends to the hexagonal boundaries separating the vortices, where the supercurrent abruptly changes direction and pseudo-magnetic field is sharply localized. These boundaries are singular planes for physical variables: supercurrent, electric polarization, order parameter derivatives are discontinuous, and pseudo-magnetic field and electric charge density diverge. The formation of these singular walls occurs abruptly when the coupling strength between the dipole superfluid and the electromagnetic field exceeds a specific critical value.

a a type-II superconductor (electric-monopole superfluid) under a magnetic field, (b) a magnetic-dipole superfluid under a pseudo-magnetic field, and (c) an electric-dipole superfluid under a pseudo-magnetic field. In all cases, we apply an external (pseudo) magnetic field in the negative z direction. The left panel plots the monopole supercurrent (not including negative charge) in (a), the magnetic-dipole supercurrent in (b), and the electric-dipole supercurrent in (c) with arrows and colors indicating the magnitude and direction. The right panel depicts the distribution of the real magnetic field in (a), and the pseudo-magnetic field in (b) and (c).

Finally, we investigate superfluids of electric dipoles, where electric and magnetic roles are reversed. Representative physical systems are exciton BECs63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78, where excitons are charge-neutral and possess an electric-dipole moment. When a magnetic field is applied to the electric-dipole, it experiences an geometric phase, called He-McKellar-Wilkens (HMW) phase79,80, that is the electric-dipole counterpart of AC phase in the magnetic-dipoles. We formulate the Ginzburg-Landau theory and obtain vortex lattices in an analogous way to the case of magnetic-dipole superfluids. Interestingly, we find that the behaviors are significantly different from those in magnetic-dipole superluids, where the supercurrent and the pseudo-magnetic field is concentrated only at vortex cores as illustrated in Fig. 1(c), resembling the behavior observed in superconductors.

The paper is organized as follows. We first develop a phenomenological theory for magnetic-dipole superfluids and derive the self-consistent equations. Within this framework, we analyze both single vortex states and vortex lattices, uncovering the emergence of singular domain walls where the derivative of the order parameter becomes discontinuous. We then extend this framework to electric-dipole superfluids in a magnetic field following a parallel approach, and demonstrate that the system exhibits a negative feedback effect that screens the pseudo-magnetic field. In the Discussion section, we compare the theories of magnetic and electric dipole superfluids with that of monopole superfluids (superconductors) and clarify the origins of their differing behaviors.

Results

Magnetic-dipole superfluid

We first focus on the magnetic-dipole superfluids under external electric field. We assume that bosons with a constant magnetic moment μ = μez form a Bose-Einstein condensate, where ez is a unit vector along the direction of the magnetic dipole moment. The considered situation applies to a spin-triplet excitonic insulator and a magnon Bose-Einstein condensate, with μ = gμB, where g ≃ 2 is the Lande g-factor and μB is the Bohr magneton. From the standard magnon gas picture, the magnetic dipole moment of the magnon is fixed along the z-direction.

Here, we introduce a geometric phase of a magnetic dipole called the Aharonov-Casher (AC) phase, and identify the fundamental feedback effect for the external electromagnetic field.

When a magnetic dipole moment μ = μez moves in an electric field E, it acquires the Aharonov-Casher (AC) phase28,

where an effective vector potential is defined by

The constant gAC( > 0) represents the strength of the spin-orbit coupling, and depends on the detail of the material. In vacuum, the gAC is μ/c2, where c is the speed of light. A simple derivation of the AC phase is presented in the “Geometric phase for dipoles” subsection in the Methods. For magnons in a typical magnetic insulator, gAC greatly enhances and is typically 106 times as large as in vacuum47,48.

Being perpendicular to ez [Eq. (2)], Am becomes a two dimensional vector with \({A}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{x}\) and \({A}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{y}\) components. The corresponding pseudo-magnetic field along z-direction is then written as

Unlike the usual vector potential in AB phase, the effective vector potential Am does not have a gauge degrees of freedom, since it is directly expressed by the electric field.

For instance, an electric field distribution

gives \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}=(-{g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{{{\mathcal{E}}}}/2)r\,{{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\phi }\) in the cylindrical coordinate (r, ϕ, z), resulting in a uniform pseudo-magnetic field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}=-{g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). Such an electric field distribution can be realized by an appropriate arrangement of external electric charges. For instance, if we put a pair of point charges + Q at r± = (0, 0, ± l), the desired electric field with \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\approx Q/(2\pi {\varepsilon }_{0}{l}^{3})\) is obtained near the origin.

When a magnetic-dipole system is placed in a spatially varying electric field that induces a pseudo-magnetic field, the system responds with positive feedback, amplifying the applied electric field. Here we explain this effect through a qualitative argument based on the classical mechanics.

We consider a situation where a magnetic-dipole polarized to z axis is placed in an external electric field Eext given by Eq. (4). Eext is radially distributed in the xy-plane as shown in Fig. 2. It induces an effective vector potential in the azimuthal direction, resulting in a negative uniform pseudo-magnetic field Bm < 0 in z direction. According to the discussion in the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods, the Hamiltonian of a magnetic dipole is expressed by \(H={({{{\bf{p}}}}+{{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}})}^{2}/(2{m}^{* })\), where m* and p represent the mass and the momentum of a magnetic dipole. Consequently, the dipole experiences a Lorentz force F = −v × Bm due to the pseudo-magnetic field and undergoes cyclotron motion29,30,31, as depicted by the gray arrow in Fig. 2.

Schematic figures of (a) externally applied electric field and (b) the electromagnetic response of magnetic dipoles. An external electric field Eint induce effective vector potential Am of the AC phase, resulting negative pseudo-magnetic field Bm < 0. The magnetic dipole experiences Lorentz force from the pseudo-magnetic field and perform cyclotron motion (circular arrow in (b)). The moving magnetic dipole then induces electric polarization P, and generate additional electric field Eint, showing positive feedback effect Eext ⋅ Eint > 0.

Generally, the motion of the magnetic dipole induces an electric dipole p = gACv × ez perpendicular to its velocity, as a reciprocal phenomenon to the AC effect47,48,49,50,51,52. See the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods for a brief derivation. When multiple magnetic dipoles exhibit the same circular motion, the macroscopic electric polarization P (the density of p) arises in the same direction, and it generates an additional electric field Eint = − P/ε0. As shown in Fig. 2, P and Eext are oppositely oriented unlike in usual dielectric materials, indicating a negative electric susceptibility. As a result, the induced electric field Eint aligns with Eext, i.e., the system exhibits a positive feedback effect (Eext ⋅ Eint > 0). In the following sections, we demonstrate that the positive feedback effect plays a crucial role in the magnetic-dipole superfluid.

Ginzburg-Landau theory

We develop a phenomenological theory for the magnetic-dipole superfluid including the AC phase. For the sake of comparison, we also present the phenomenological Ginzburg-Landau theory for conventional superconductors in the “Ginzburg-Landau theory of superconductors (electric-monopole superlfuids)” subsection in Methods to be directly compared with the following formulation for magnetic-dipole superfluids.

We consider charge neutral Bose particles with a magnetic moment μ = μez forming a Bose-Einstein condensate. Utilizing an analogy to the Ginzburg-Landau theory of superconductivity or rotating atomic BEC, the free energy FGL of the magnetic-dipole superfluid is given by

where m* is the effective mass, and \(\Psi ({{{\bf{r}}}})=| \Psi ({{{\bf{r}}}})| \exp \left(i\theta ({{{\bf{r}}}})\right)\) is the order parameter, or the macroscopic wavefunction of the magnetic-dipole superfluid. We assume α > 0 and β > 0 for the stability of the BEC. The parameter α depends on a temperature T and is given by \(\alpha (T)\propto {({T}_{c}-T)}^{\nu }\), where Tc is a critical temperature and ν is a critical exponent. The superfluid satisfies the Ginzburg-Landau (GL) equation

The first term in the integral of Eq. (5) is the kinetic energy density, and it should correspond to n*(m*v*^2/2) where \({n}^{* }={\left\vert \Psi \right\vert }^{2}\) is the the superfluid density and v* is the velocity. Then, the associated supercurrent density, jm = n*v*, is written as

Eq. (7) has an equivalent form to a conventional superconductor under magnetic field, except that the vector potential is replaced with the effective vector potential Am for the AC effect. The supercurrent flows in the direction of the effective vector potential Am, which is perpendicular to both the electric field E and the magnetic dipole moment ∥ez.

As argued in the previous section, a current of magnetic-dipole moment induces an electric polarization47,48,49,50,51,52,53. In the present case, the polarization P (density of electric dipole moment) induced by the magnetic-dipole supercurrent jm is given by

A brief derivation of this relation is presented in the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods. By definition, P does not have a z-component. The electric field can then be expressed as

where Eext represents the external electric field contributed from electric charges outside the system, and ε0 is the permittivity of free space. For simplicity, we assume the polarization of the superfluid is entirely generated by the supercurrent, ignoring the polarization of normal state. In standard terms of electromagnetism, Eext corresponds to the the electric displacement field D = ε0Eext, and Eq. (9) is written as E = (D − P)/ε0.

From Eqs. (2), (8), and (9), the effective vector potential is written as

where \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}={g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{{{{\bf{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\times {{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\) and \({{{{\bf{j}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{\parallel }\) is the xy-component of jm. The corresponding pseudo-magnetic field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={(\nabla \times {{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}})}_{z}\) is given by

where \(\rho = -\nabla \cdot {{{\mathbf{P}}}}\) is the polarization charge density. When we consider the response of the system to an external electric field Eext, we solve the GL equation [Eq. (6)] self-consistently with Eq (7) and (10).

The same set of equations can also be derived by variation of the total Helmholtz free energy including the electrostatic field. For the magnetic-dipole superfluid, it is given by

as a functional of the external field D(r) = ε0Eext(r). Equation (12) is one of the principal results of our paper. It can be derived by considering a quasi-static process where the external electric field is slowly introduced to the dipole superfluid. The detailed calculation is provided in the “Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids” subsection in Methods. It is straightforward to check that Eqs. (6) and (10) are obtained by the equilibrium conditions δF/δΨ = 0 and δF/δAm = 0, respectively. (See the “Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids” subsection in Methods).

To highlight the essential scales of the system and relevant parameters, we rewrite the equations in a dimensionless form. Similar to the standard Ginzburg-Landau framework for superconductors, we normalize the position r as \(\tilde{{{{\bf{r}}}}}={{{\bf{r}}}}/\xi\) and the spatial derivative as \(\tilde{\nabla }=\xi \nabla\), where

is the coherence length of the superfluid. The order parameter is normalized as \(\tilde{\Psi }=\Psi /{\Psi }_{\infty }\) in units of a uniform BEC value \({\Psi }_{\infty }=\sqrt{\alpha /\beta }\), the effective vector potential as \({\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}/(\hslash /\xi )\), and energy functional as \({\tilde{F}}_{{{{\rm{GL}}}}}={F}_{{{{\rm{GL}}}}}/({\alpha }^{2}{\xi }^{3}/\beta )\). As a result, the superfluid free energy [Eq. (5)] is expressed in a dimensionless form as

Eq. (6) becomes

The supercurrent [Eq. (7)], polarization [Eq. (8)], and polarization charge density are normalized as

where \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={{{{\bf{j}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}/{j}_{0}\), \(\tilde{{{{\bf{P}}}}}={{{\bf{P}}}}/({g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{j}_{0})\) and \(\tilde{\rho }=\rho /({g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{j}_{0}/\xi )\) with \({j}_{0}=\hslash {\Psi }_{\infty }^{2}/({m}^{* }\xi )\). The effective vector potential, Eq. (10), becomes

with

The parameter η is a dimensionless quantity that characterizes the strength of the electrostatic coupling in the superfluid. The η depends on temperature as \(\eta (T)\propto \alpha (T)\propto {({T}_{c}-T)}^{\nu }\) according to Eq. (20). The pseudo-magnetic field [Eq. (11)] is written as

where \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}/(\hslash /{\xi }^{2})\). In this unit, the pseudo-magnetic flux penetrating a given area becomes equal to the AC phase integrated along the boundary, and hence the dimensionless flux quanta is given by \({\tilde{\phi }}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{0}=2\pi\).

The total free energy of Eq. (12) is normalized as

where \(\tilde{F}=F/({\xi }^{3}{\alpha }^{2}/\beta )\), \(\tilde{{{{\bf{D}}}}}={{{\bf{D}}}}/( \, {g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{j}_{0})\) and \(\tilde{{{{\bf{E}}}}}={{{\bf{E}}}}/( \, {g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{j}_{0}/{\varepsilon }_{0})\).

Equations (15), (16) and (19) are a set of the self-consistent equations. The latter two equations can be readily solved for \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) and \({\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) as

An important observation is that the presence of η ( > 0) enhances the supercurrent and the vector potential by decreasing the denominator \(1-\eta | \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}\). This is the positive feedback effect argued in the “Magnetic-dipole superfluids” subsection in Results. The equations also imply a singular behavior when the denominator vanishes, i.e., \(\eta | \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}=1\). This will be discussed in the next subsection.

Single-vortex state

In the following, we consider an infinitely-large magnetic-dipole superfluid under an external field of \({\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=(-| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}| r/2){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\phi }\), which gives a uniform pseudo-magnetic field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\). (See the “Magnetic-dipole superfluids” subsection in Results). Here we set \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\) (along − z direction). We assume a superfluid solution of the form

with a single vortex of n = + 1 along the z-axis. We solve the set of self-consistent equations [Eqs. (6), (7) and (10)] by a numerical iteration. (See the “Technical details of self-consistent numerical calculations” subsection in Methods). The results for different η parameters are summarized in Fig. 3. Here we plot (a) the absolute order parameter \(f(r)=| \tilde{\Psi }(r)|\), (b) the azimuthal component of the supercurrent \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\), which is equal to the radial component of electric polarization, \(\tilde{P}(r)\), and (c) polarization charge density \(\tilde{\rho }(r)\), which is related to the internal pseudo-magnetic field \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}={\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}-{\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\) by \(\tilde{\rho }=-{\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}/\eta\). The lower panels display the two-dimensional plots of the distribution of \(| \tilde{\Psi }|\), \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\), \(\tilde{\rho }\) on the xy plane at η = 1. In the plot of \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\), the color and brightness indicate its direction and magnitude, respectively.

Self-consistent solution of a magnetic-dipole superfluid with a single vortex of n = 1 under \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02({r}_{* }=10)\). In top panels, we plot (a) absolute order parameter \(f(r)=| \tilde{\Psi }(r)|\), (b) azimuthal component of the supercurrent \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\) (equal to the radial electric polarization, \(\tilde{P}(r)\)), and (c) polarization charge density \(\tilde{\rho }(r)\) (equal to the internal pseudo-magnetic field), where different colors correspond to different η's. Inset of (a) is a magnified plot near r* = 10, where dashed lines indicate the value of η−1/2. The lower panels display the two-dimensional plots of (a) f(r), (b) \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\) and (c) \(\tilde{\rho }(r)\) on the xy plane, at the parameter of η = 1. In (b), the arrows represent the magnetic-dipole supercurrent \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\), while the color and brightness indicate its direction and magnitude, respectively, as shown in the inset. In (c), the arrows represent the polarization \(\tilde{{{{\bf{P}}}}}(r)\).

First, we focus on η = 0 (blue curve in Fig. 3), where the electrostatic feedback is absent. In this case, the supercurrent [Eq. (23)] is given by \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}=| \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}(\tilde{\nabla }\theta +{\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}})\) where \(\tilde{\nabla }\theta =(1/r){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\phi }\). Its azimuthal component then becomes \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)=f{(r)}^{2}(1/r-| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}| r/2)\), which vanishes at the radius \({r}_{* }\equiv \sqrt{2/| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}| }\) ( = 10 in the present case). The r* is the radius such that the pseudo-magnetic flux penetrating the region r < r* is equal to a quantum flux \({\tilde{\phi }}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{0}=2\pi\).

As the parameter η is increased from zero, we observe that the vanishing point of \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) still remains at r = r*, while its slope at r = r* becomes gradually steeper, as seen in Fig. 3(b). This is expected from Eq. (23) where the supercurrent amplitude is enhanced by the denominator \(1-\eta | \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}\). In η ≳ 1, interestingly, \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\) becomes a step-like function, i.e., the direction of the azimuthal supercurrent abruptly changes at r = r*. Consequently, the pseudo-magnetic field exhibits a sharp peak according to the relation \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}-{B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\propto \nabla \times {{{{\bf{j}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) [Eq. (21)], which is clearly observed in Fig. 3(c). In terms of electric quantities, this corresponds to a high magnitude of ∇ ⋅ P, i.e., a sharply-localized polarization charge density at r = r*. As η increases beyond 1, the width of the discontinuous wall at r = r* becomes extremely narrow, and the charge density as well as the pseudo magnetic field diverge.

The step-like behavior of \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\) in η ≳ 1 can be explained by vanishing denominator \(1-\eta | \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}\) in Eq. (23). In the present case, Eq. (23) is written as

In the numerical solutions presented in Fig. 3, the f (r) of η ≳ 1 exhibits a kink structure in the vicinity of r*, which is well described by

Then the denominator of Eq. (26) is written as \(\frac{1}{f{(r)}^{2}}-\eta \approx 2{\eta }^{3/2}a| r-{r}_{* }|\) in the lowest order in r − r*. Noting the bracket in Eq. (26) can be approximated by \((-2/{r}_{* }^{2})(r-{r}_{* })\), we end up with a step function

where \({{{\rm{sgn}}}}(x)\equiv x/| x|\). Here we note that the maximum of f(r) is η−1/2 [Eq. (27)], i.e., the f(r) is tuned in such a way that the denominator of Eq. (26) vanishes right at r = r*. This cancels with the original zero of the supercurrent, resulting in a step function. In the actual numerical result, the kink of f(r) at r = r* is rounded so that the maximum is slightly lower than η−1/2 as observed in the inset of Fig. 3(a), which prevents the denominator from completely vanishing. Consequently, the step structure in \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) is smoothed into a continuous, yet rapidly-changing function.

It should also be noted that the total flux inside the radius r = r* remains quantized even when the internal field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}={B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}-{B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\) is included. This can be understood by the following consideration: By applying the Stokes theorem to Eq. (21), the flux of the internal field in r < r* becomes \({\int}_{r < {r}_{* }}{B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}{d}^{2}r\propto {\oint }_{r = {r}_{* }}{{{{\bf{j}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\cdot d{{{\bf{r}}}}\), which vanishes since jm = 0 at r = r*. Therefore, the total flux inside r* is contributed solely by the external field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\), which is quantized by definition. Zero flux of \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}\) inside the radius r* is equivalent to a zero net charge within the region.

It should also be emphasized that the domain wall found in our calculation differs from the conventional case in the following way: In superconducting domain walls, the order parameter undergoes an abrupt π phase change, causing it to vanish at the domain wall81. In contrast, in the singular domain wall of magnetic-dipole superfluids, the order parameter does not vanish; instead, its derivative (i.e., the supercurrent) vanishes and changes sign.

To demonstrate the energetic advantage of the vortex state in pseudo-magnetic fields, we investigate the total free energy F with and without a vortex. Here we consider a finite system of the disc with radius R = 40, and obtain the self-consistent solutions with no vortex (n = 0), a single vortex (n = 1), a single anti-vortex (n = − 1) at the center of the disc. We impose a boundary condition such that the order parameter vanishes at the edge of the disc r = R. For the obtained solutions, we calculate the total free energy of the system F given by Eq. (12).

Figure 4 plots the relative total free energy of n = 1 (solid curves) and n = − 1 (dashed curves) compared to the n = 0 state, as a function of the external pseudo-magnetic field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\). The different colors correspond to different η. Let us first consider the case of η = 0 (blue curve), which corresponds to a standard superfluid without the electrostatic feedback effect. At \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=0\), the uniform solution (n = 0) is the ground state, while the vortex states (n = ± 1) are degenerate in higher energy. When \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\) is increased, the relative energy of the n = 1 state decreases, and it finally becomes the lowest at \(B={B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{* }(R)\equiv (1+2\log R)/(1+{R}^{2})\). The critical field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{* }(R)\) can be regarded as a pseudo-magnetic field at which the system of size R allows a single vortex to enter. The anti-vortex state (n = −1) is always higher in energy as naturally expected.

When we increase η, the critical field at which the n = 1 state becomes stable monotonically decreases, i.e., the n = 1 vortex state is stabilized in a smaller field. It is stark contrast to the typical behaviors of superconductivity, where the critical field Hc1 increases as the coupling to the electromagnetic field increases82. This corresponds to a transition from type II regime with the formation of the vortices to the type I regime where the Meissner effect occurs.

Vortex lattice

When the pseudo-magnetic field is much greater than \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{* }(R)\), we expect that multiple vortices enter the superfluid, forming of a vortex lattice. Here we demonstrate the emergence of a vortex lattice in a dipole superfluid by numerically solving Eqs. (15), (16) and (19) self-consistently. We assume a triangular lattice with primitive lattice vectors a1 = a(1, 0) and \({{{{\bf{a}}}}}_{2}=a(1/2,\sqrt{3}/2)\) where a is the lattice constant. The lattice constant a is determined by the requirement that the unit cell contains exactly a quantum flux \({\tilde{\phi }}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{0}=2\pi\), giving \({a}^{2}=2\pi {r}_{* }^{2}/\sqrt{3}\).

We assume a periodic current profile jm(r + ai) = jm(r), which ensures \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})={{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}+{{{{\bf{a}}}}}_{i})\) by Eq. (19). Since the periodic vector potential can only give zero flux on average, the total pseudo-magnetic flux is contributed solely by the external field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\). Therefore, we can assume that the total vector potential, including the external field, obeys the periodicity,

where L(l1, l2) = l1a1 + l2a2 is a lattice translation vector with integer li. The order parameter then satisfies the magnetic Bloch condition,

The single-valuedness of the order parameter is guaranteed when unit cell spanned by a1 and a2 accommodates an integer multiple of flux quanta. We solve the self-consistent equation by a numerical iteration with the periodic boundary condition of Eqs. (29) and (30), starting from an initial state with a single vortex per unit cell.

Figure 5 summarizes the obtained superfluid vortex lattice for η = 0.8, 1 and 1.1, in \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\). Each figure presents spatial maps of (a) the absolute order parameter f(r), (b) the supercurrent \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\), and (c) the charge density \(\tilde{\rho }({{{\bf{r}}}})\,(=-\eta {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}))\), respectively. We observe that the single vortex structure argued in the previous section are periodically arranged in a consistent manner. The supercurrent jm circulates in the counterclockwise direction in each cell [Fig. 5(b)], or equivalently, the polarization P is arranged radially with respect to the vortex. When η exceeds 1, significantly, the supercurrent distribution extends upto the edge of the honeycomb unit cell, and its direction abruptly changes across the domain wall as in the single vortex case. As a result, the polarization charge (i.e., the internal pseudo-magnetic field) is sharply concentrated at the domain wall, forming a bold honeycomb domain-wall network as seen in Fig. 5(c). We also have negative polarization charge localized around the vortex cores, which exactly cancels with those on the domain wall, resulting in a zero net charge. Equivalently, the integral of Bint over a unit cell is vanishing, so that the total pseudo-magnetic flux remains per unit cell equal to that of the external field \({B}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\).

Self-consistent vortex lattice of a magnetic-dipole superfluid for η = 0.8, 1 and 1.1, in \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\). Each figure presents spatial maps of (a) the absolute order parameter \(f({{{\bf{r}}}})=| \tilde{\Psi }({{{\bf{r}}}})|\), (b) the supercurrent \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\), and (c) the charge density \(\tilde{\rho }({{{\bf{r}}}})\,(=-{\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})/\eta )\), respectively. In (b), the arrows represent the magnetic-dipole supercurrent \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}(r)\), while the color and brightness indicate its direction and magnitude, respectively, as shown in the inset.

We have also systematically performed the same self-consistent calculations for different angles ranging from 60∘ (triangular lattice) to 90° (square lattice). We find that the triangular vortex lattice always has the lowest free energy for all values of η.

If we vary \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) within the range \(| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}| \ll 1\), it primarily affects the size of the vortex lattice while preserving its qualitative features. However, when \({\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\) becomes large, on the order of 1, we expect the vortex lattice to melt into a liquid phase, similar to other superfluid systems83.

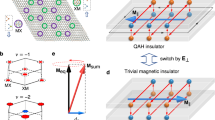

Electric-dipole superfluids

The above argument for magnetic-dipole superfluids can be directly extended to electric dipoles, where the roles of electric and magnetic fields reversed. Such a situation can be realized in excitonic condensates, where excitons (bound states of an electron and a hole) are charge-neutral and possess an electric dipole moment63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,84.

In the following, we present a phenomenological theory for electric-dipole superfluids interacting with a magnetic field, paralleling the discussion of magnetic-dipole superfluids in the previous sections. However, the electric-dipole superfluids show distinct behavior, owing to its negative feedback effect, while the magnetic-dipole superfluids show positive feedback effect.

While the magnetic dipole interacts with the electric field through the AC phase, the electric dipole p = pez interacts with the magnetic flux density B by means of the He-McKellar-Wilkens (HMW) phase77,78,79,80,85,86,87,88,89,

where Ap is the effective vector potential given by

where gHMW = p for vaccum. A simple derivation of HMW phase is presented in the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods. The corresponding pseudo-magnetic field along z-direction is then written as

Here the pseudo-magnetic field is given by a spatially-dependent magnetic field. In the following, B and Bext represent real magnetic fields, not pseudo-magnetic fields.

In contrast to the magnetic dipole case, the electric dipole exhibits the negative feedback against the external field. Figure 6 shows the schematic figure illustrating the response of electric dipoles, corresponding to Fig. 2 for magnetic dipoles. Here we apply radially-distributed magnetic field Bext, which gives the pseudo-magnetic field Bp in the − z direction. According to the Hamiltonian \(H={({{{\bf{p}}}}-{{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}})}^{2}/(2{m}^{* })\), the electric-dipole experiences a Lorentz force F = + v × Bp due to the pseudo-magnetic field, leading to the cyclotron motion. (See the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods.) The motion of the electric dipoles generates a magnetic-dipole μ = − gHMWv × ez, giving magnetization M (the density of μ). (See the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods.) The M and Bext are oppositely oriented, indicating a diamagnetic response. This aligns with the negative dielectric response in the magnetic dipole case. The magnetization contributes to the additional magnetic field Bint = μ0M. Since Bext ⋅ Bint < 0, the feedback is negative.

Schematic figures of (a) externally applied magnetic field and (b) the electromagnetic response of electric dipoles, which correspond to Fig. 2 for magnetic dipoles. An external magnetic field Bext (orange) induce effective vector potential Ap (purple) of HMW phase, resulting negative pseudo-magnetic field Bp < 0. The electric dipole experiences Lorentz force from the pseudo-magnetic field and perform cyclotron motion (gray). The moving electric dipole induces a magnetization M, and they generate additional magnetic field Bint, showing negative feedback effect Bext ⋅ Bint < 0.

This negative feedback effect contrasts with the positive feedback effect in the magnetic-dipole system. The opposite features are due to the fact that the electric field in the magnetic-dipole case corresponds to H-field (not B-field) in the electric-dipole case, and that generally H-field and B-field induced by magnetic dipoles are oppositely directed (e.g., in magnetic materials). Indeed, if we replace + and − charges of induced electric dipole in Fig. 2 with N and S magnetic monopoles, we reproduce the situation of Fig. 6, where the induced H-field is oriented outward, similar to Eint in Fig. 2. Therefore the induced B-field points inward.

We assume that the Ginzburg-Landau free energy functional for electric-dipole superfluids is given by

where m* is the effective mass of a quasiparticle having an electric dipole and Ψ(r) is the order parameter. The Ginzburg-Landau equation is written as

The supercurrent is expressed as

Just as the current of a magnetic dipole induces electric polarization, the current of electric dipole jp induces the magnetization by

A brief derivation of this relation is presented in the “Geometric phases for dipoles” subsection in Methods. The magnetic flux density can be expressed as

where Bext is the external magnetic flux density, and μ0 is the permeability. In the standard notation of electromagnetism, Bext corresponds to the magnetic field H = Bext/μ0, and Eq. (38) is written as B = μ0(H + M). From Eqs. (32), (37), and (38), the total magnetic field induces the effective vector potential

with \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}={g}_{{{{\rm{HMW}}}}}\,{{{{\bf{B}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}\times {{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\).

Equations (35) and (39) can alternatively be derived by variation of the total free energy including the magnetic field. In the present case, it is appropriate to use the Gibbs free energy G[H(r), T] = F[B(r), T] − ∫ dr B(r) ⋅ H(r) rather than the Helmholtz free energy F[B(r), T], since the external magnetic field H is fixed. According to the argument of the “Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids” subsection in Methods, the Gibbs free energy is written as

It is straightforward to check that Eqs. (35) and (39) are obtained by the equilibrium conditions δG/δΨ = 0 and δG/δAp = 0, respectively (See, the “Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids” subsection in Methods).

Similar to the argument for magnetic-dipole systems, the equations (36) and (39) can be expressed in a dimensionless form as,

where the variables with tilde represent dimensionless quantities and we defined a dimensionless parameter

which corresponds to η for magnetic-dipole superfluids. The two equations Eqs. (41) can be solved for \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) and \({\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) as

In contrast to the corresponding formula for the magnetic-dipole case, Eqs. (23) and (24), ηp enters with positive sign in the denominator \(1+{\eta }_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}| \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}\). Therefore, the ηp > 0 gives s a negative feedback reducing the applied field.

When an electric-dipole superfluid is subjected to a pseudo-magnetic field Bp (a spatially-dependent magnetic field), the system also forms a vortex lattice, while the electro-magnetic field texture is completely distinct from the case of magnetic-dipole superfluids due to the negative feedback effect.

Here, we perform analyses of a single vortex state and a vortex lattice in the electric-dipole superfluid, aligning with the corresponding calculations for the magnetic-dipole cases. First, we consider a single vortex state under an external field of \({\tilde{{{{\bf{A}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=(-| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}| r/2){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\phi }\) with \({\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\). We assume an anti-vortex state \(\tilde{\Psi }(r,\phi ,z)=f(r){e}^{-i\phi }\), where the negative sign in the phase factor corresponds to the negative sign of the effective vector potential in Eq. (36). In Fig. 7, we plot (a) the absolute value of the order parameter \(f(r)=| \tilde{\Psi }(r)|\), (b) the azimuthal component of the supercurrent \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(r)\), which is equal to the radial component of magnetization, \(\tilde{M}(r)\), and (c) the abolute value of pseudo-magnetic field \(| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(r)|\), for different ηp parameters.

In top panels, self-consistent solutions of an electric-dipole superfluid with a single vortex of n = −1 under \({\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\,({r}_{* }=10)\) are summarized. We plot (a) absolute order parameter \(f(r)=| \tilde{\Psi }(r)|\), (b) azimuthal component of the supercurrent \({\tilde{j}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(r)\) (equal to the radial magnetization, \(\tilde{M}(r)\)), and (c) absolute value of total pseudo-magnetic field \(| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(r)|\), where different colors correspond to different ηp's. Inset of (c) is a magnified plot near \(| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(r)| =0\). In lower panels, self-consistent vortex lattice of an electric-dipole superfluid under \({\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}=-0.02\,({r}_{* }=10)\) are summarized. We display the two-dimensional plots of (d) \(f(x,y)=| \tilde{\Psi }(x,y)|\), (e) \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(x,y)\) and (f) \(| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(x,y)|\) on the xy plane, at the parameter of η = 0.5. The colors and brightness in (e) indicate the direction and magnitude of the supercurrent \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(x,y)\), respectively.

As seen in Fig. 7(b), the supercurrent is suppressed owing to the negative feedback effect (i.e. the denominator \(1+{\eta }_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}| \tilde{\Psi }{| }^{2}\) in Eq. (43)). This behavior is stark contrast to magnetic-dipole superfluids, where the supercurrent is amplified by the positive feedback effect. Furthermore, as is shown in Fig. 7(c), the pseudo-magnetic field is sharply concentrated at the vortex core, whereas away from the core (r ≫ ξ), it converges to a nonzero constant,

This equation is obtained by taking the curl of Eq. (44) with \(| \tilde{\Psi }(r){| }^{2}=1\). It is worth noting that the total flux inside the radius \({r}^{* }\equiv \sqrt{2/| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}| }(=10)\) is always quantized, as demonstrated by the same reasoning presented in the “Single-vortex states” subsection in Results.

We also calculate vortex lattice states of electric-dipole superfluids, in the same manner as described in the “Vortex lattices” subsection in Results. In Fig. 7, we show the plots of the distributions of (d) \(f(x,y)=| \tilde{\Psi }(x,y)|\), (e) \({\tilde{{{{\bf{j}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(x,y)\), (f) \(| {\tilde{{{{\boldsymbol{B}}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}(x,y)|\) on the xy plane at η = 0.5. We observe that the single-vortex structures are periodically arranged in a consistent manner; the pseudo-magnetic field is primarily concentrated around the vortices and remains nearly constant away from them at the value given by Eq. (45).

Discussion

We have shown that magnetic and electric dipole superfluids under a pseudo-magnetic field form vortex lattices with distinctly different electromagnetic field textures. The magnetic-dipole system exhibits a positive feedback effect for the applied field, resulting in discontinuous domain walls that separate neighboring vortices. In contrast, the electric-dipole system shows a negative feedback effect, leading to a strong suppression of the pseudo-magnetic field away from the vortex core. The latter behavior resembles the vortex lattice in type-II superconductors (electric-monopole superfluids), but with a significant difference: the magnetic field in superconductors decays exponentially away from the vortex, whereas the pseudo-magnetic field in electric-dipole superfluids converges to a constant value proportional to ∝ 1/(1 + ηp). In this section, we discuss the origins of these different behaviors among the three distinct classes of systems — superconductors, magnetic-dipole superfluids, and electric-dipole superfluids — through their key equations.

In the three cases, the superfluid free energy FGL [Eqs. (5), (34), (62)] and the supercurrent [Eqs. (7), (36), (64)] share the same functional form with respect to the corresponding vector potential, i.e., A for superconductors, and Am (Ap) for magnetic (electric)-dipole superfluid. Accordingly, the supercurrent and vector potential obey the same relationship. When the phase θ is constant, in particular, we have the London-type equation j ∝ − A, jm ∝ Am, and jp ∝ − Ap.

However, a difference lies in the relationship between the vector potential and the real magnetic/electric field:

As an inverse effect, the relationship between the supercurrent and the induced magnetization/polarization is also different, as

Note that Equations (46) and (47) represent different aspects of the same phenomenon. In fact, Eq. (47) can be derived from the variation of the free energy with the same form, under condition of Eq. (46).

In Eqs. (46) and (47), the crucial difference between monopoles and dipoles is in the existence/absence of the spatial derivative ∇ . For the monopole case, in particular, these relations with London’s equation j ∝ A lead to ∇ × ∇ × A ∝ A or ∇2B ∝ B, resulting in an exponential decay of the magnetic field (Meissner effect). In contrast, in dipole superfluids, the spatial derivative term is absent, resulting in a linear relationship between the external field and the induced field. Consequently, the external fields are amplified or suppressed by a factor of (1−η)−1 in magnetic-dipole superfluids and \({(1+{\eta }_{p})}^{-1}\) in electric-dipole superfluids, where the opposite signs in front of η and ηp correspond to positive and negative feedback, respectively.

Finally, the origin of the opposite feedback effects in the magnetic and electric dipole systems is explained as follows. Both systems share the parallel relationships described by Eqs. (46) and (47), which lead to the same anti-parallel orientations between the external field Eext / Bext and the induced dipole density P / M. Here we note that the negative sign in M in Eq. (47) cancels with the negative sign in jp ∝ − Ap. However, opposite signs come in the relations between the induced dipole density and the feedback fields: Eint = − P/ε0 and Bint = + μ0M, resulting in positive and negative feedback, respectively.

The domain formation with singular domain walls is a particularly remarkable feature of magnetic-dipole superfluids, with no counterparts in other physical systems. In order to experimentally observe this, we need a magnetic-dipole superfluid satisfying \(\eta ={g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}^{2}{\Psi }_{\infty }^{2}/({m}^{* }{\varepsilon }_{0}) \, \gtrsim \, 1\) [Eq. (20)], which requires large spin-orbit coupling, high density of condensate, and small effective mass. We provide a rough estimation of η for a magnon BEC in Yttrium Iron Garnet (YIG), a representative example of currently available materials. In magnetic insulators, gAC is typically 106 times as large as in vacuum47,48. The superfluid density can be assumed about \({\Psi }_{\infty }^{2} \sim 1{0}^{21}\,{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{-3}\)11. The effective mass is obtained by m* = ℏ2/(2JSa2) by considering ferromagnetic Heisenberg model, where J is the nearest-neighbor ferromagnetic exchange coupling, S is the effective spin and a is the lattice constant. Using material parameters from experiments, we have J ≈ 1.37 K, S ≈ 14.3, and a ≈ 12.4 Å90,91. Under these conditions, we have η ~ 0.36. We also present an estimation of the magnitude of pseudo-magnetic field. Considering the spatially modulating electric field Eq. (4), the dimensionless pseudo-magnetic field is given by \(| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}| ={g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}{{{\mathcal{E}}}}/(\hslash /{\xi }^{2})\). In the case of YIG, the value \(| {\tilde{B}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}| =0.02\) used in our calculations corresponds to a reasonable condition with an electric field gradient of \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}=0.01\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\,{{{{\rm{nm}}}}}^{-2}\) and a superfluid coherence length of ξ = 1 nm.

Throughout this study, we assumed that the bosons constituting the superfluid have a fixed dipole moment. In the case of magnons, this assumption is justified because magnon creation, as defined by the Holstein-Primakoff transformation, corresponds to a spin-lowering operator, where each magnon is associated with a dipole moment of gμB. For excitons as electric dipoles, on the other hand, the dipole moment can change if the relative orbital state of the electron-hole pair is excited (e.g., from 1s to 2p). We assume that the external field is moderate enough to prevent such excitations. Incorporating the variation of the dipole moment would introduce additional nontrivial effects on the properties of dipole superfluids.

We also neglected dipole-dipole interactions between bosons. While this effect is generally considered small in magnon and exciton systems, it is known to give rise to nontrivial phenomena in alkali spinor Bose-Einstein condensates due to the anisotropic nature of dipole-dipole interactions92. Investigating its impact on the electromagnetic response is an interesting direction for future work.

We have theoretically studied magnetic and electric dipole superfluids subjected to a pseudo-magnetic field induced by a spatially modulated electromagnetic field. Using a Ginzburg-Landau phenomenological theory that incorporates the geometric AC/HMW phase, we obtained self-consistent solutions by fully accounting for the feedback effect of the electromagnetic field induced by the response current. Under a pseudo-magnetic field, both electric and magnetic dipole superfluids spontaneously form vortex lattices but exhibit distinct field textures. When the electrostatic coupling parameter η exceeds a critical value, magnetic dipole superfluids form a honeycomb lattice with a singular domain wall with diverging pseudo-magnetic fields and polarization charges. This behavior contrasts starkly with conventional superconductors (monopole superfluids). In electric dipole superfluids, the pseudo-magnetic field is concentrated only at vortex cores as in conventional superconductors, but it does not decay exponentially away from the vortices. Despite sharing parallel formulations, magnetic and electric dipole systems exhibit opposite features due to a sign difference in the feedback effect for the applied field. These findings highlight novel field textures and self-organized structures unique to magnetic dipole superfluids, opening new directions in exploring superfluid systems with unconventional electromagnetic responses.

Methods

Geometric phase for dipoles

We provide parallel derivations of the Aharonov-Casher (AC) phase28 for magnetic dipoles, and He-McKellar-Wilkens (HMW) phase79,80 for electric dipoles.

We present a simplified derivation of the original Aharonov-Casher (AC) phase28 in vacuum as a relativistic effect. We consider a particle with a magnetic-dipole μ = μ ez, which is moving with velocity v. The magnetic-dipole is equivalent to a small loop electric current on the xy-plane. When the loop current moves with velocity v relative to the rest frame, we (an observer in the rest frame) observe electric charge density ρ = v ⋅ j/c2 from Lorentz covariance. Here j is the current density in the moving frame fixed to the loop current. When a square loop current is moving along the x-axis, therefore, two sides along x are positively and negatively charged as illustrated in Fig. 8(a), resulting in an electric dipole

where gAC = μ/c2.

If an external electric field E is present, the particle has an electrostatic potential energy − p ⋅ E. Thus, the Lagrangian for the particle is given by

where m* is a mass of the particle. As the second term is transformed as p ⋅ E = gAC(v × ez) ⋅ E = − gAC(E × ez) ⋅ v, the Lagrangian is written as

where

Since Eq. (50) is formally equivalent to the Lagrangian of an electron in a magnetic field, Am plays the role of the effective vector potential for the magnetic-dipole. Therefore, the moving magnetic-dipole acquires the AC phase [Eq. (1)].

The He-McKellar-Wilkens (HMW) phase79,80 can be derived in a similar manner to the AC phase. We consider an electric-dipople constituting a pair of point charges + q and − q located at z = + d/2 and z = − d/2, where p = qd. If the electric-dipole moves in the x-direction with velocity v, the two point charges ± q generate counter-propagating electric currents along x, as illustrated in Fig. 8(b). This gives rise to a magnetic moment in the y-direction as

where gHMW = p.

If an external magnetic field B is present, the particle has an magnetostatic potential energy − μ ⋅ B. Thus, the Lagrangian for the particle is given by

where m* is a mass of the particle. As the second term is transformed as μ ⋅ B = − gHMW(v × ez) ⋅ B = gHMW(B × ez) ⋅ v, the Lagrangian is written as

where

Since Eq. (54) is formally equivalent to the Lagrangian of an electron in a magnetic field, Ap plays the role of the effective vector potential for the electric-dipole. Therefore, the moving electric-dipole acquires the HMW phase [Eq. (31)].

Alternatively, this HMW phase can directly be derived from the Aharonov-Bohm (AB) phase as follows. When the dipole moves horizontally along the x-axis, from x to x + Δx, the positive and negative charges acquire Aharonov-Bohm (AB) phases given by \({\theta }_{\pm }=(\pm q/\hslash ){\int}_{{C}_{\pm }}d{{{\bf{r}}}}\cdot {{{\bf{A}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\), where C± are the paths followed by the positive and negative charges, respectively. The total geometric phase for the dipole is given by θHMW = θ+ + θ−, and it becomes \((q/\hslash )[{\int}_{{C}_{+}}-{\int}_{{C}_{-}}]d{{{\bf{r}}}}\cdot {{{\bf{A}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})=(p/\hslash ){B}_{y}({{{\bf{r}}}})\Delta x\), where we used Stokes’s theorem and p = qd. The result is consistent with Eqs. (31) and (32).

Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids

We present the derivation of the Helmholtz free energy of magnetic dipole superfluids [Eq. (12)], and the Gibbs free energy of electric dipole superfluids [Eq. (40)], paralleling the argument for the conventional superconductors.

We derive the expression of the Helmholtz free energy F[D(r), T], Eq. (12). We consider a quasi-static, isothermal process where the external electric field, or D(r), is slowly introduced to the magnetic-dipole superfluid with the temperature fixed. Here, we consider a general situation where the external electric field D (and consequently E and P) depends on position, to account for the system under the pseudo-magnetic field, which needs spatially dependent electric field [Eq. (3)]. We assume that the system is at the thermal equilibrium of given D(r) and T at every moment of the process. As in a general dielectric material, the change in the Helmholtz free energy from the initial state (i) with D = 0 to the final state (f) with D = D(r) is written as

Here \(\int_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{{{\rm{f}}}}}\cdots \delta {{{\bf{D}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) represents the functional integral in D(r).

The last term in Eq. (56) coincides with the change of GL energy functional FGL[Ψ, Am], because the infinitesimal change in FGL in the process is written as

where we used Eqs. (2), (7) and (8). Here we note that the variation δFGL should also include δFGL/δΨ and δFGL/δΨ*, while these terms just vanish because we assume that the GL equation Eq. (6) holds throughout the quasi-static process. From Eq. (56) and Eq. (57), we obtain Eq. (12).

We can readily check that the self-consistent equations are derived by the variation of the total Helmholtz free energy with D fixed. Eq. (6) is given by δF/δΨ = 0, since δF/δΨ = δFGL/δΨ. Eq. (10) is obtained by δF/δAm = 0, noting

where we used relations P = D − ε0E and \({{{\bf{E}}}}={g}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}^{-1}({{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\times {{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}})+{E}_{z}{{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\).

We derive the expression of the Gibbs free energy G[H, T], Eq. (40). We consider a quasi-static, isothermal process where the external magnetic field H is slowly introduced to the electric-dipole superfluid with temperature fixed. The change in the Gibbs free energy from the initial state (i) with H = 0 to the final state (f) with H is given by

We can show that the last term in Eq. (59) coincides with the change in FGL by the following argument. In a quasi-static process, the infinitesimal change in the GL free energy functional is given by

where we used Eq. (36), and we noted that δFGL/δΨ = δFGL/δΨ* = 0 throughout the process. Equations (59) and (60) lead to the Eq. (40).

We check that self-consistent equations are derived by the variation of the total Gibbs free energy while fixing H. Eq. (35) is straightforwardly derived from δG/δΨ = 0 since δG/δΨ = δFGL/δΨ. Eq. (39) is obtained by δG/δAp = 0, noting

where we used relations B = μ0(H + M) and \({{{\bf{B}}}}={g}_{{{{\rm{HMW}}}}}^{-1}({{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\times {{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}})+{B}_{z}{{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{z}\).

Ginzburg-Landau theory for superconductors (electric-monopole superfluids)

We review the standard Ginzburg-Landau theory82,93 for superconductor, to provide a basis for comparison with the corresponding theory for dipole superfluids. The Ginzburg-Landau free energy functional for conventional superconductors is given by

where me is the electron mass, and e ( > 0) is the elementary charge. Ψ(r) represents the superconducting order parameter and B = ∇ × A represents the magnetic flux density, where A is the vector potential. The Ginzburg-Landau equation for the order parameter is given by

The superconducting current is described by the London equation, giving

and this superconducting current produces the magnetization M by Maxwell equations, giving

The total Gibbs free energy including magnetic field contribution is given by

which can be derived by considerations similar to those in the “Derivation of total free energy for dipole superfluids” subsection in Methods. We can readily check that self-consistent equations are derived by the variation of the total Gibbs free energy with H fixed: Eq. (63) is obtained from δG/δΨ = 0 since δG/δΨ = δFGL/δΨ. Eq. (65) is derived by δG/δA = 0, noting

where we used relations B = μ0(H + M) and B = ∇ × A. Here, Aext is the vector potential of the external magnetic field defined by μ0H = ∇ × Aext.

By combining Eq. (64) with Eq. (65), we have ∇ × ∇ × A = − λ−2A, where \(\lambda =\sqrt{{m}_{e}/(2{\mu }_{0}{e}^{2}| \Psi {| }^{2})}\) is the London’s penetration depth. Thus, we obtain ∇2B = λ−2B, which shows the exponential decay of the magnetic flux density (Meissner effect).

Technical details of self-consistent numerical calculations

We present the technical details of the numerical calculation. In the calculations in the main text, we numerically solve the GL equation [Eq. (6)] self-consistently with Eqs. (7) and (10) under a given external field, following the procedure outlined below.

First we set an initial configuration with Ψ = Ψ(0) and \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(0)}}}}}(\equiv {{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ext}}}}})\). Then, we calculate the supercurrent jm using Eq. (7). From obtained jm, we obtain the updated vector potential \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(1)}}}}}\) using Eq. (10). We then obtain the order parameter Ψ(1) by solving GL equation [Eq. (6)] with \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(1)}}}}}\). We go back to the first stage with Ψ = Ψ(1) and \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}={{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(1)}}}}}\), to obtain Ψ = Ψ(2) and \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(2)}}}}}\). We repeat the procedure until ∣Ψ(n+1) − Ψ(n)∣ and \(| {{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{(n+1)}-{{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{(n)}|\) become sufficiently small.

In the procedure to obtain Ψ by the GL equation, we minimize FGL with respect to Ψ instead of directly solving the GL equation, since the GL equation is equivalent to δFGL/δΨ* = 0. Specifically, we optimize Ψ by repeating steps of

where Δt > 0 is a positive constant. At every step, the FGL consistently decreases because the change of FGL at the step is given by

We repeat this procedure until ∣δFGL∣ ~ 0, to obtain Ψ satisfying the GL equation.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

Ikeda, A. et al. Signature of spin-triplet exciton condensations in lacoo3 at ultrahigh magnetic fields up to 600 t. Nat. Commun. 14, 1744 (2023).

Jiang, Z. et al. Spin-triplet excitonic insulator: The case of semihydrogenated graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 166401 (2020).

Sun, Q.-f & Xie, X. C. Spin-polarized ν = 0 state of graphene: A spin superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245427 (2013).

Yang, H. et al. Spin-triplet topological excitonic insulators in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 109, 075167 (2024).

Nishida, H., Miyakoshi, S., Kaneko, T., Sugimoto, K. & Ohta, Y. Spin texture and spin current in excitonic phases of the two-band hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 99, 035119 (2019).

Wang, R., Erten, O., Wang, B. & Xing, D. Y. Prediction of a topological p + ip excitonic insulator with parity anomaly. Nat. Commun. 10, 210 (2019).

Liu, H., Jiang, H., Xie, X. C. & Sun, Q.-f Spontaneous spin-triplet exciton condensation in abc-stacked trilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 86, 085441 (2012).

Sethi, G., Zhou, Y., Zhu, L., Yang, L. & Liu, F. Flat-band-enabled triplet excitonic insulator in a diatomic kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 196403 (2021).

Sethi, G., Cuma, M. & Liu, F. Excitonic condensate in flat valence and conduction bands of opposite chirality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 186401 (2023).

Wei, H., Chao, S.-P. & Aji, V. Excitonic phases from weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 196403 (2012).

Demokritov, S. O. et al. Bose–einstein condensation of quasi-equilibrium magnons at room temperature under pumping. Nature 443, 430–433 (2006).

Bozhko, D. A. et al. Supercurrent in a room-temperature bose–einstein magnon condensate. Nat. Phys. 12, 1057–1062 (2016).

Bozhko, D. A. et al. Bogoliubov waves and distant transport of magnon condensate at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 10, 2460 (2019).

Olsson, K. S. et al. Pure spin current and magnon chemical potential in a nonequilibrium magnetic insulator. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021029 (2020).

Divinskiy, B. et al. Evidence for spin current driven bose-einstein condensation of magnons. Nat. Commun. 12, 6541 (2021).

Nikuni, T., Oshikawa, M., Oosawa, A. & Tanaka, H. Bose-einstein condensation of dilute magnons in tlcucl3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 5868–5871 (2000).

Rüegg, C. et al. Bose–einstein condensation of the triplet states in the magnetic insulator tlcucl3. Nature 423, 62–65 (2003).

Giamarchi, T., Rüegg, C. & Tchernyshyov, O. Bose–einstein condensation in magnetic insulators. Nat. Phys. 4, 198–204 (2008).

Aczel, A. A. et al. Field-induced bose-einstein condensation of triplons up to 8 k in sr3cr2o8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 207203 (2009).

Sonin, E. Spin currents and spin superfluidity. Adv. Phys. 59, 181–255 (2010).

Zapf, V., Jaime, M. & Batista, C. D. Bose-einstein condensation in quantum magnets. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 563–614 (2014).

Yuan, W. et al. Experimental signatures of spin superfluid ground state in canted antiferromagnet cr2o3 via nonlocal spin transport. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1098 (2018).

Esaki, N., Akagi, Y. & Katsura, H. Electric field induced thermal hall effect of triplons in the quantum dimer magnets Xcucl3 (X = Tl, K). Phys. Rev. Res. 6, L032050 (2024).

Kimura, S. et al. Ferroelectricity by bose–einstein condensation in a quantum magnet. Nat. Commun. 7, 12822 (2016).

Kimura, S. et al. Magnetoelectric effect in the quantum spin gap system tlcucl3. Phys. Rev. B 95, 184420 (2017).

Kimura, S., Matsumoto, M. & Tanaka, H. Electrical switching of the nonreciprocal directional microwave response in a triplon bose-einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 217401 (2020).

Sakurai, K., Kimura, S., Awaji, S., Matsumoto, M. & Tanaka, H. Spin-driven ferroelectricity in the quantum magnet tlcucl3 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 102, 064104 (2020).

Aharonov, Y. & Casher, A. Topological quantum effects for neutral particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 319–321 (1984).

Meier, F. & Loss, D. Magnetization transport and quantized spin conductance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 167204 (2003).

Nakata, K., Kim, S. K., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Magnonic topological insulators in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 96, 224414 (2017).

Nakata, K., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Magnonic quantum hall effect and wiedemann-franz law. Phys. Rev. B 95, 125429 (2017).

Wang, Y., Zhu, Z.-G. & Su, G. Magnon spin photogalvanic effect induced by aharonov-casher phase. Phys. Rev. B 110, 054434 (2024).

Su, Y. & Wang, X. R. Chiral anomaly of weyl magnons in stacked honeycomb ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 96, 104437 (2017).

Wagh, A. & Rakhecha, V. Quantum physics with neutrons. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 37, 485–563 (1996).

Sangster, K., Hinds, E. A., Barnett, S. M., Riis, E. & Sinclair, A. G. Aharonov-casher phase in an atomic system. Phys. Rev. A 51, 1776–1786 (1995).

Avishai, Y., Totsuka, K. & Nagaosa, N. Non-abelian aharonov-casher phase factor in mesoscopic systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 084705 (2019).

Avishai, Y. & Band, Y. B. Aharonov–bohm and aharonov–casher effects in meso-scopic physics: a brief review. arXiv:2302.06300 (2023).

König, M. et al. Direct observation of the aharonov-casher phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 076804 (2006).

Shekhter, R. I., Entin-Wohlman, O., Jonson, M. & Aharony, A. Magnetoconductance anisotropies and aharonov-casher phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 037704 (2022).

Yamane, Y., Fukami, S. & Ieda, J. Theory of emergent inductance with spin-orbit coupling effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 147201 (2022).

Balatsky, A. V. & Altshuler, B. L. Persistent spin and mass currents and aharonov-casher effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1678–1681 (1993).

Grosfeld, E. & Stern, A. Observing majorana bound states of josephson vortices in topological superconductors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 11810–11814 (2011).

Elion, W. J., Wachters, J. J., Sohn, L. L. & Mooij, J. E. Observation of the aharonov-casher effect for vortices in josephson-junction arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2311–2314 (1993).

Seidov, S. S. & Fistul, M. V. Quantum dynamics of a single fluxon in josephson-junction parallel arrays with large kinetic inductances. Phys. Rev. A 103, 062410 (2021).

Zhang, X., Liu, T., Flatté, M. E. & Tang, H. X. Electric-field coupling to spin waves in a centrosymmetric ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 037202 (2014).

Serha, R. O., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Towards an experimental proof of the magnonic aharonov-casher effect. Phys. Rev. B 108, L220404 (2023).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Balatsky, A. V. Spin current and magnetoelectric effect in noncollinear magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057205 (2005).

Liu, T. & Vignale, G. Electric control of spin currents and spin-wave logic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 247203 (2011).

Go, G., An, D., Lee, H.-W. & Kim, S. K. Magnon orbital nernst effect in honeycomb antiferromagnets without spin–orbit coupling. Nano Lett. 24, 5968–5974 (2024).

Hirsch, J. E. Overlooked contribution to the hall effect in ferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B 60, 14787–14792 (1999).

Sun, Q.-f, Guo, H. & Wang, J. Spin-current-induced electric field. Phys. Rev. B 69, 054409 (2004).

Tokura, Y., Seki, S. & Nagaosa, N. Multiferroics of spin origin. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 076501 (2014).

Solovyev, I., Ono, R. & Nikolaev, S. Magnetically induced polarization in centrosymmetric bonds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 187601 (2021).

Zhu, Y., Kleinherbers, E., Levitov, L. & Tserkovnyak, Y. Proposal for spin-superfluid quantum interference device (2025).

Bruno, P. & Dugaev, V. K. Equilibrium spin currents and the magnetoelectric effect in magnetic nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 72, 241302 (2005).

Chen, W. & Sigrist, M. Spin superfluidity in coplanar multiferroics. Phys. Rev. B 89, 024511 (2014).

Nakata, K., van Hoogdalem, K. A., Simon, P. & Loss, D. Josephson and persistent spin currents in bose-einstein condensates of magnons. Phys. Rev. B 90, 144419 (2014).

Nakata, K. Optomagnonic josephson effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104402 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Non-abelian braiding in spin superconductors utilizing the aharonov-casher effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 106804 (2022).

Wang, Z.-b, Sun, Q.-f & Xie, X. C. The electric “meissner effect” in spin superconductor. Eur. Phys. J. B 86, 496 (2013).

Bao, Z.-q, Xie, X. C. & Sun, Q.-f Ginzburg–landau-type theory of spin superconductivity. Nat. Commun. 4, 2951 (2013).

Sun, Q.-f, Jiang, Z.-t, Yu, Y. & Xie, X. C. Spin superconductor in ferromagnetic graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 214501 (2011).

Jérome, D., Rice, T. M. & Kohn, W. Excitonic insulator. Phys. Rev. 158, 462–475 (1967).

Kohn, W. Excitonic phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 439–442 (1967).

Butov, L. V., Zrenner, A., Abstreiter, G., Böhm, G. & Weimann, G. Condensation of indirect excitons in coupled alas/gaas quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 304–307 (1994).

Khveshchenko, D. V. Ghost excitonic insulator transition in layered graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 246802 (2001).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose–einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691–694 (2004).

Cercellier, H. et al. Evidence for an excitonic insulator phase in 1t − tise2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 146403 (2007).

Min, H., Bistritzer, R., Su, J.-J. & MacDonald, A. H. Room-temperature superfluidity in graphene bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 78, 121401 (2008).

Kogar, A. et al. Signatures of exciton condensation in a transition metal dichalcogenide. Science 358, 1314–1317 (2017).

Li, J. I. A., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K., Hone, J. & Dean, C. R. Excitonic superfluid phase in double bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 13, 751–755 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation in two-dimensional atomic double layers. Nature 574, 76–80 (2019).

Jauregui, L. A. et al. Electrical control of interlayer exciton dynamics in atomically thin heterostructures. Science 366, 870–875 (2019).

Ma, L. et al. Strongly correlated excitonic insulator in atomic double layers. Nature 598, 585–589 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Evidence for an excitonic insulator state in ta2pd3te5. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011046 (2024).

Balatsky, A. V., Joglekar, Y. N. & Littlewood, P. B. Dipolar superfluidity in electron-hole bilayer systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 266801 (2004).

Dubinkin, O., May-Mann, J. & Hughes, T. L. Theory of dipole insulators. Phys. Rev. B 103, 125129 (2021).

Jiang, Q.-D., Bao, Z.-q, Sun, Q.-F. & Xie, X. C. Theory for electric dipole superconductivity with an application for bilayer excitons. Sci. Rep. 5, 11925 (2015).

He, X.-G. & McKellar, B. H. J. Topological phase due to electric dipole moment and magnetic monopole interaction. Phys. Rev. A 47, 3424–3425 (1993).

Wilkens, M. Quantum phase of a moving dipole. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 5–8 (1994).

Stone, M. & Roy, R. Edge modes, edge currents, and gauge invariance in px + ipy superfluids and superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 69, 184511 (2004).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity (Dover, 1996).

Cooper, N. R., Wilkin, N. K. & Gunn, J. M. F. Quantum phases of vortices in rotating bose-einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 120405 (2001).

Doshi, D. & Gromov, A. Vortices as fractons. Commun. Phys. 4, 44 (2021).

Wei, H., Han, R. & Wei, X. Quantum phase of induced dipoles moving in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2071–2073 (1995).

Dowling, J. P., Williams, C. P. & Franson, J. D. Maxwell duality, lorentz invariance, and topological phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2486–2489 (1999).

Lepoutre, S., Gauguet, A., Trénec, G., Büchner, M. & Vigué, J. He-mckellar-wilkens topological phase in atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 120404 (2012).

Chen, W., Horsch, P. & Manske, D. Flux quantization due to monopole and dipole currents. Phys. Rev. B 87, 214502 (2013).

Wood, A. A., McKellar, B. H. J. & Martin, A. M. Persistent superfluid flow arising from the he-mckellar-wilkens effect in molecular dipolar condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 250403 (2016).

Gilleo, M. A. & Geller, S. Magnetic and crystallographic properties of substituted yttrium-iron garnet, 3y2o3 ⋅ xm2o3 ⋅ (5 − x)fe2o3. Phys. Rev. 110, 73–78 (1958).

Tupitsyn, I. S., Stamp, P. C. E. & Burin, A. L. Stability of bose-einstein condensates of hot magnons in yttrium iron garnet films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 257202 (2008).

Lahaye, T., Menotti, C., Santos, L., Lewenstein, M. & Pfau, T. The physics of dipolar bosonic quantum gases. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72, 126401 (2009).

El-Nabulsi, R. A. & Anukool, W. On nonlocal ginzburg-landau superconductivity and abrikosov vortex. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 644, 414229 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Yshai Avishai, Joji Nasu, Takeo Kato and Manato Fujimoto. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grants No. JP20H01840, No. JP20H00127, No. JP20K14415, No. JP21H05236, No. JP21H05232, No. JP23KJ1518, No. JP24K06921 and by JST CREST Grant No. JPMJCR20T3, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kazuki Yamamoto, Takuto Kawakami and Mikito Koshino performed the calculations and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Rami Ahmad El-Nabulsi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, K., Kawakami, T. & Koshino, M. Electromagnetic response in dipole superfluids. Commun Phys 8, 171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02088-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02088-z