Abstract

Decoherence severely limits the performance of quantum processors, posing challenges to reliable quantum computation. Probabilistic error cancellation, a quantum error mitigation method, counteracts noise by quasiprobabilistically simulating (non-physical) inverse noise operations. However, existing formulations of physical implementability, quantifying the minimal cost of simulating non-physical operations using physical channels, do not fully account for the experimental constraints, since noise also affects the cancellation process, and not all physical channels are experimentally accessible. Here, we generalize the physical implementability to encompass arbitrary convex sets of experimentally available quantum states and operations. Within this generalized framework, we demonstrate noiseless error cancellation with noisy Pauli operations and analyze the bias of noisy cancellation. Furthermore, we establish connections between generalized physical implementability and quantum information measures, e.g. diamond norm, logarithmic negativity, and purity. These findings enhance the practical applicability of probabilistic error cancellation and open new avenues for robust quantum information processing and quantum computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In quantum computation, an ideal quantum circuit is unitary1. However, the imperfection of quantum devices will lead to the noises in the performance of quantum circuits. The physical operations on a quantum system are thought to be completely positive and trace-preserving (CPTP), which is also called the quantum channel2. The Markov noise in quantum circuit can be depicted as a quantum noise channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\)3.

In practice, the noise channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) can be evaluated by the quantum process tomography, even though the cost may be exponentially overwhelming4. With the knowledge of the noise channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\), we would like to implement its inverse \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) to cancel the impact of the noise. However, only the unitary channels have quantum channels as its inverse \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) is also CPTP5. It is impossible to physically implement a quantum channel to cancel the incoherence error.

Although the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) may not be a quantum channel but rather a Hermitian-preserving and trace-preserving (HPTP) operation, it can be simulated with a series of quantum channels. If it can be decomposed as the affine combination of quantum channels, the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) can be simulated by the quasiprobability mixture, of which the absolute value of coefficients in the affine decomposition are normalized into a probabilistic distribution. The noise inverse operation is the probabilistic mixture of quantum channels with signatures of coefficients in this distribution up to normalization. This quantum error mitigation method is the probabilistic error cancellation (PEC)6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Furthermore, the reduced dynamics with correlated initial conditions might not always be CPTP18,19. The quasiprobability mixture technique allows for simulating such HPTP operations with quantum channels, which helps to analyze the non-Markov noise. The logarithm of the minimal cost, or overhead Cem in the context of quantum error mitigation6,10,20, to simulate an HPTP operation with CPTP channels is defined as the physical implementability of the HPTP operation10,21. It has also been shown that the physical implementability of the noise inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) characterizes the decoherence effects of noise channel22.

In the PEC method, by employing the Pauli-twirling technique6,17,23,24,25,26,27, the error channel and the noises in experiments can be randomized compiled to be Pauli diagonal. By employing the cycle benchmarking28,29 and error reconstruction technique30,31, the error model of the noisy circuit can be constructed17,26,32. In principle, with the well-performed randomized compiling and sufficient estimation of error model, the PEC method is believed to be free of bias6. However, in practice, the PEC method will not always be unbiased. The bias can be induced from the violation of the error model33,34. This may be caused by the inaccurately randomized compiling or the inaccurate error model estimation34.

Moreover, to cancel the error in noisy circuit, additional Pauli gates need to be introduced in the implementation of the PEC, which would also be affected by the noises in the additional circuit. Intuitively, the noises on Pauli gates \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) may be single-qubit errors, which is not comparable to the error to be canceled. However, due to the cross-talk between qubits35, the noises of multi-qubit Pauli gates may not be the tensor product of noises of single-qubit Pauli gates in experiments. Therefore, the noises introduced in Pauli gates are not simply the single-qubit errors, and it is possible to yield a considerable bias of cancellation. If the noises in the cancellation are less than the error to be canceled, the PEC has a positive effect on the performance of a quantum circuit. Otherwise, the cancellation makes the performance of the quantum circuit even worse. The similar imperfection in quantum error correction leads to the famous threshold theorem36,37,38,39, which may be the main obstacle to realizing fault-tolerant quantum computation. The error mitigation technique is not believed to have an inevitable threshold phenomenon6. Nevertheless, the noisy implementation of the cancellation will also lead to additional bias.

In this paper, we investigate the noisy cancellation of the error channel. We generalized the physical implementability to an arbitrary given convex set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) of quantum operations and states that are available in experiments, and its general properties are introduced in Methods. Using the generalized physical implementability, we demonstrate the optimal method to noiseless cancel a given error channel with noisy Pauli gates in Results. We also consider the bias of the noisy cancellation with the noisy Pauli gates and the bias of the error model violation. Moreover, we illustrate the connection between the generalized physical implementability and other quantum information measures, such as the diamond norm, logarithmic negativity, and purity in Discussion.

Results

Noiseless cancellation with noisy Pauli Basis

Let \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) be an HPTP operation on system A, and then it can be decomposed as the affine combination of CPTP channels \({{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}\)

where ∑ini = 1. If all ni ≥ 0, it can be implemented by a probabilistic mixture of CPTP channels \({{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}\). Otherwise, for any ni ≤ 0, we should rewrite it as

where Z = ∑i ∣ni∣ and qi = ∣ni∣/Z. Then, \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) can be simulated by using the probabilistic mixture of CPTP channels \({{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}\) with sign \({{{\rm{sgn}}}}({n}_{i})\). The quantity Z is the cost of CPTP channels for the implementation of a single HPTP operation. The physical implementability21 is defined as the logarithm of the minimal cost of CPTP operations for HPTP operations

where \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}\) denote the set of CPTP channels.

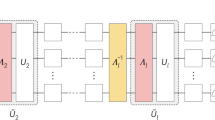

For the PEC quantum error mitigation method, the error channel is mitigated by simulating its inverse operation. Let \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\equiv {{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{\lambda }\circ {{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }\) be the error channel (in the left action) of an ideal quantum circuit \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}\) whose noisy circuit in experiments is \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{\lambda }\), as shown in Fig. 1. The quasiprobability decomposition of the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) of error channel is

where \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) are called noisy basis. With the Pauli-twirling technique, we consider the error model as the Pauli diagonal error, and the noisy basis \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) are Pauli gates. Then, the ideal expectation of the operator \(\widehat{O}\) relative to the initial state ρ is

The PEC mitigated unitary circuit \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{{{{\rm{PEC}}}}}\) is shown in Fig. 1a.

a The noisy implementation \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{\lambda }\) of a quantum circuit \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}\) with error channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). The PEC method cancels this error by implementing its inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\). b However, the noisy realization of the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\) incompletely cancels the error \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). With the noises of cancellation, the PEC operation needs to be modified as \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}={\Theta }^{-1}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1})\), where Θ is the map from the ideal Pauli gates \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) to noisy gate \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\), such that its noisy realization \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda {{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}\) cancels the error \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) complete.

Ideally, the Pauli gates \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) are physically realizable quantum channels, but the inevitable noises in experiments lead to the noisy Pauli gates \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\). Here, we encounter two different kinds of noise, one is the error channel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) in the quantum circuit \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}\) of our interest, and another is the noises in the noisy basis \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\), which is used to cancel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). To clearly distinguish them, the former one \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is called error, while the latter is called noise in the following. The noisy realization of the inverse of the error channel thus is

which cannot cancel the error channel completely, as Fig. 1a

Instead, if we ideally apply a modified PEC operation of the error channel, shown in Fig. 1b,

its noisy realization is

We can select the parameters qi to cancel \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) completely, i.e., \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda {{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\), based on the knowledge of the noises on Pauli gates.

In precise, with the Pauli twirling techniques, we still assume that the noisy Pauli gates are Pauli diagonal

The noise map Θ can be calibrated on the experimental devices. If the noisy Pauli gate \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\) are not completely indistinguishable, i.e., \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\) are linearly independent, the noise linear map Θ is invertible. Then, the modified PEC operation of the error channel is

where \({q}_{i}={\sum }_{j}{r}_{j}{\Theta }_{ji}^{-1}\).

There still exists a problem that which model of the noisy quasiprobability cancellation of error \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is optimal. To depict the cost of noisy cancellation, We thus define the generalized physical implementability for any HPTP operation \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) with respect to noisy CPTP operations as

where the minimization is the quasiprobability decompostion \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}={\sum }_{i}{x}_{i}{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}\) with respect to noisy CPTP channels \(\Theta ({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})\). Here, Θ denotes the noise map for the basis of the operation space. Moreover, for other quantum information processing tasks involving the quasiprobability decomposition, their optimal costs can also be quantified by several types of implementability functions similar to the generalized physical implementability as defined. For the general definition and properties of the implementability function, see Methods.

With the generalized physical implementability, the optimal cost of the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) is \({p}_{\Theta ({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1})\). Assume that the linear map Θ is invertible, by the affine invariance of the implementability function (see Methods), we have

where \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}=\exp \nu\) is the (exponential) physical implementability. Since the optimal cancellation of a mixed-unitary channel with ideal CPTP channels is the decomposition with the unitaries21, the optimal cancellation of modified PEC cancellation operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}^{-1}\) is the quasiprobability decomposition with respect to the ideal Pauli channels \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) with quasiprobability

The optimal cancellation of \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) with respect to the noisy CPTP channels \(\Theta ({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})\) thus is the quasiprobability decomposition with respect to the noisy Pauli channels \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\) with qi in Eq. (13). In conclusion, with the matrix Θij measured from the noisy Pauli basis \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\), the inverse operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) of the error channel can be optimally canceled under the noisy Pauli basis \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{i}\).

Here, we illustrate the result with simple examples. Assume the noise is a depolarizing error on one qubit, ideally, the error channel of evolution with error rate λ is

It is not difficult to show that its inverse is

If the error rate λ ≪ 1, we approximate \(\Theta ({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i})\approx {{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\), for \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}={{{\mathcal{X}}}},{{{\mathcal{Y}}}},{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\), we have

which is in coincidence the known results of the depolarizing error7. Then, we assume that \(\Theta ({{{\mathcal{I}}}})={{{\mathcal{I}}}}\) and \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}}=\Theta ({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i})={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{\alpha }\circ {{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) for \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}={{{\mathcal{X}}}},{{{\mathcal{Y}}}},{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\). It can be calculated as

Let \(a=\frac{1+3{(1-\lambda )}^{\alpha }}{4},b=\frac{1-{(1-\lambda )}^{\alpha }}{4}\), we have

Thus, the quasiprobability, Eq. (13), of optimal cancellation in terms of \({({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{I},{{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{X},{{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{Y},{{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{Z})}^{T}\) is obtained from Eqs. (15) and (18).

For an arbitrary Pauli diagonal error, since it is CPTP, in general, it can be written as the exponential of Lindblad operators3.

where the Lindblad operator can be written as

Thus, the error channel is

where \({\omega }_{i}=(1+{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-2{\lambda }_{i}})/2\). This error model is called the Pauli-Lindblad noise model17. The inverse operation of the error channel is

where \({\mu }_{i}=(1+{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{2{\lambda }_{i}})/2\). There are two ways to simulate the inverse operation of the error channel. One is to simulate \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\) as a whole channel, and the other is to simulate each layer \(\left({\mu }_{i}{{{\mathcal{I}}}}+(1-{\mu }_{i}){{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\right)\), separately. No matter the ideal or noisy cancellations, the second way may have more cost than the first way21, since the sub-multiplicity of the implementability function (see Methods). For the formalism simplicity, however, we only consider the noisy cancellation in the second way. By measuring the noise map Θ of Pauli gates in the experiment, the optimal noisy cancellation is given as

Invertibility of noise map

The above discussion is based on the assumption that the linear map Θ is invertible. When the map Θ is not invertible, there is no perfect noisy cancellation. The invertibility of Θ is equivalent to \(\det \Theta \ne 0\). In practice, assuming the true value Θ0 of the noise map is not invertible, i.e., \(\det {\Theta }_{0}=0\), the random fluctuation from the finite measurements will lead to the noise map Θ measured from the experiments to be invertible, \(\det \Theta \ne 0\). Therefore, the condition \(\det \Theta \ne 0\) calculated with the experimental data does not certainly imply the invertibility of the noise map Θ. In the following, we discuss the condition the noise map Θ is invertible under finite measurements in experiment.

For simplicity, denote the true value of the determinant of the linear map \(\det {\Theta }_{0}\) as \({\det }_{0}\). With the Chebyshev’s inequality, it can be shown that the probability for the case that the true value of the determinant of the linear map Θ is not invertible is expressed as

Therefore, for a given number N of measurements, the linear map Θ is invertible with the probability (1 − δ) if the map Θ satisfies that

where D is the dimension of the map Θ. For the details of calculation, see Supplementary Note V.

Bias of noisy cancellation

For the noisy cancellation, without mitigating the noises in simulation of inverse noise operation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1}\), we would like to estimate the bias of the noisy cancellation \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}=\Theta ({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1})\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). The bias of the expectation of Pauli operator \(\widehat{O}\) is expressed as

where we denote \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}={{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\to A)\). With \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}=\Theta ({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1})\), we have

where \({\Theta }_{\lambda }=1-{\min }_{i}{\Theta }_{ii}\) is the maximal error probability of the noisy Pauli gates. This result allows for estimating the upper bound of the bias in experiments, with the cost of simulation \({p}_{\Theta ({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1})\) and the calibration of Pauli gates Θλ. For the details of the calculation, see Supplementary Note V.

If the circuit consists of L layers of operations \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}={\prod }_{i = 1}^{L}\circ {{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\), where \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\) is the i-th layer, there are two strategies to realize the PEC method. One is to cancel the error of each layer \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) separately, and the other is to cancel the total error \({\prod }_{i}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) directly. The circuits are shown in Fig. 2. Let the noisy realization of circuit be \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{\lambda }={\overleftarrow{\bigcirc }}_{i = 1}^{L}{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i\lambda }\), where \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i\lambda }={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\circ {{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\), then the error channel of the circuit is

where \({\tilde{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{i}=({\overleftarrow{\bigcirc}}_{j\ > \ i}^{L}{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{j})\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\circ ({\overrightarrow{\bigcirc}}_{j\ > \ i}^{L}{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{j}^{{{\dagger}} })\). Here, the arrow above the symbol ◯ represents the acting direction of layers.

We consider the bias of noisy cancellation of the total error of the circuit for these two different strategies. For the separate cancellation method, the noisy realization of the error-canceled circuit is

where \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i{{{\rm{PEC}}}}}={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\circ {{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}\). The error of the separate cancellation is

where \({\tilde{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{i}=({\overleftarrow{\bigcirc}}_{j > i}^{L} {{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j} ) \circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}_{i\lambda}^{-1} \circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}_i \circ ({\overrightarrow{\bigcirc}}_{j > i}^{L} {{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{j}^{{{\dagger}}})\). The bias of the noisy separate cancellation is

For the detailed calculation, see Supplementary Note V. On the other hand, by applying Eq. (27), the bias of the direct cancellation method is

Since the upper bound of the bias of the direct cancellation method, Eq. (32), is less than the upper bound of the bias of the separate cancellation method, Eq. (31), the direct cancellation method appears to be more accurate than the separate cancellation method.

However, there are more results with the detailed analysis of the noisily canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). We consider a particular case that the noisily canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is a CPTP quantum channel, \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})=1\). For instance, if the noises are uniform on the Pauli gates, \(\Theta ({{{\mathcal{E}}}})={{{\mathcal{N}}}}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\), with the commutativity of Pauli diagonal operation, it preserves \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}={{{\mathcal{N}}}}\in {{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\to A)\). The bias of the direct cancellation is bounded by

since \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})=1\). For the separate cancellation method, assume the noisily canceled error for each layer \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) is a CPTP quantum channel; it can be shown that the bias is bounded by

For details of the calculation, see Supplementary Note V.

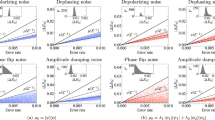

The numerical results for comparing the two cancellation methods with small and large error rates are shown in Fig. 3. When the error rate is sufficiently small, e.g., λ = 0.05 as used in Fig. 3a–c, the noisily canceled errors for both separate and direct cancellations are CPTP, Fig. 3c. Thus, the bias is limited by the CPTP upper bounds, as shown in Fig. 3a for the separate cancellation Eq. (34) and Fig. 3b for the direct cancellation Eq. (33). The bias of direct cancellation is much smaller than the separate cancellation method. When the error rate is moderately large, e.g., λ = 0.5 as used in Fig. 3d–f, the noisily canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) of each layer error is still CPTP, thus the noisily canceled error \({\prod }_{i}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) of separate cancellation is also CPTP, as shown in Fig. 3f, and the bias of separate cancellation is still limited by Eq. (34), as shown in Fig. 3d. For the direct cancellation method, the noisily canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is CPTP, when the layer is shallow. However, it will no longer be CPTP as the layer increases, as ilustrated in Fig. 3f. The bias of direct cancellation increases exponentially with the layer number accroding to Eq. (32) in and will surpass the CPTP upper bound of separate cancellation Eq. (34), see Fig. 3e where the CPTP upper bound is labeled by a dotted curve. Thus, for a large error rate, the separate cancellation method is more effective than the direct cancellation method.

a, b, d, and e, Colored filling regions denote the biases of expectations for different Pauli operators, and solid curves denote the median of the biases of the operator expectations. Dashed curves denote the distance between the imperfectly canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\) in the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{\mathcal{I}}}}-{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\), which upper bounds the bias of the operator expectations by Eq. (26). Dotted curves denote the CPTP upper bound of \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{\mathcal{I}}}}-{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\), see Eqs. (33) and (34) for the direct and separate cancellation methods, respectively. The error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{j}\) is assumed to be the same for each layer, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{j}={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0}\), and the error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0}\) as well as the noises \({{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}\) on Pauli gates \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}\) are randomly sampled from the Pauli-Lindblad error model (21), with a fixed single-layer error rate λ = ∑iλi. c and f, Dotted dashed curves denote the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\) of the imperfectly canceled error for direct and separate cancellation methods. a--c, For a small error rate λ = 0.05, since the imperfectly canceled errors \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) (c) are CPTP for circuits with a layer number less than 20, the biases of both the separate (a) and direct (b) cancellation methods are limited by the CPTP upper bound, Eqs. (33) and (34), and the bias of the direct cancellation is smaller than the separate cancellation method. d–f For a large error rate λ = 0.5, since the imperfectly canceled error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) for the direct cancellation method (f) will eventually not be CPTP with the cumulation of errors \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0}^{L}\). The bias increases exponentially and surpasses the CPTP bound (e), as the layer number L grows. However, the error \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) for the separate cancellation method (f) is still CPTP, since each the error of individual layer \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0\lambda }^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0}\) is CPTP. The bias of separate cancellation is still bounded by the CPTP upper bound (f). For details of simulation, see Supplementary Note VI.

When the error rate is large enough, the noisily canceled error for the individual layer will not be CPTP. The bias of both the separate and direct cancellation methods will exponentially increase with the layer number, see Eqs. (32) and (31). However, for the direct cancellation method, the error of L layers of circuits may not be invertible under a finite measurement precision in the experiment, since its error rate is typically L times the error rate of the one for the individual layer. By considering the map \({{\Xi }}({{{\mathcal{N}}}})={{{\mathcal{E}}}}\circ {{{\mathcal{N}}}}\), where \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is the error to be canceled, the condition of invertibility of \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is given by Eq. (25), as

In brief, for the case where the circuit is shallow and the error rate is sufficiently small, the direct cancellation method is more accurate. If the circuit is deep and the error rate is large, the separate cancellation method is more accurate.

Intuitively, one may expect a clear criterion for choosing between these two cancellation methods. The condition for the criterion requires the solution of a multi-variable polynomial equation \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}(\Theta ({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{-1})\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})=1\) in the components νi of \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) and the element Θij of Θ. However, the solution for the criterion is very complicated, where the error rate λ of \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) and the maximum error probability Θλ of the noise map Θ are not sufficient to determine the criterion. In experiments, to verify whether the noisily canceled error is CPTP requires the complete estimation of the noise map Θ, which provides sufficient information for the noiseliess cancellation, thus it need not to consider the bias of noisy cancellation. Therefore, there is no feasible and reliable criterion to distinguish which method, direct or separate, has better performance. To quantitatively determine this criterion will be a topic in further investigations. Moreover, the error model used for PEC may be inaccurate, which also hinders the verification of the noisily canceled CPTP error.

Bias of Inaccurate error model

The case where the error model is inaccurate will also induce the bias of the PEC method. This is not the main target of this work and has been investigated in other works34. The bias of the PEC from the inaccurate error model is estimated by employing the diamond norm

where \({\delta }_{O}=| {\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{PEC}}}}}-{\left\langle O\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{exact}}}}}|\) is the bias of the PEC method with the inaccurate error model, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) is the exact error channel of i-th layer, and \({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{i}\) is the inaccurate error model learned from experiment. With the estimation of the diamond norm of the operation \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}-{\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{j}^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{j}\), the bias is calculated as

where \({\gamma }_{i}={p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{i}^{-1})\),

\({\nu }_{0}^{(j)}=\frac{1}{{4}^{n}}{\sum }_{k}{r}_{k}^{(i)}\) is the component of \({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{j}^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{j}\) in \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\), \({r}_{k}^{(i)}={f}_{{P}_{k}}^{{{{\rm{meas}}}}}/{f}_{{P}_{k}}^{{{{\rm{mod}}}}}\) is the ratio of the measured fidelity to the model fidelity of the Pauli gate Pk, and

Since the diamond norm is the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}\), Eq. (51), the bias from the inaccurate error model is compatible with the bias from the noisy cancellation operation estimated in this work. The total bias of the noisy PEC with the inaccurate error model is upper bounded as

We next consider the Pauli diagonal error model \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}=\exp {{{\mathcal{L}}}}({\lambda }_{i})\), where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}({\lambda }_{i})={\sum }_{i}{\lambda }_{i}({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{i}-{{{\mathcal{I}}}})\). Assume real error parameters \(\{{\lambda }_{i}^{(j)}\}\) with deviations from the parameters \(\{{\widehat{\lambda }}_{i}^{(j)}\}\), measured in experiments for the jth layer. The mitigated error channel for the jth layer is

where \({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}_{j}\) is the target error channel for the mitigation, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{j}\) is the real error channel, and \(\Delta {\lambda }_{i}^{(j)}={\lambda }_{i}^{(j)}-{\widehat{\lambda }}_{i}^{(j)}\). The total mitigated error channel is

where \(\Delta {\lambda }_{i}={\sum }_{j}\Delta {\lambda }_{i}^{(j)}\). The bias of the expectation of the Pauli operator \(\widehat{O}\) is upper bounded by

It is crucial whether the mitigated error \({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is CPTP or not, and the error is called under-mitigated or over-mitigated if it is CPTP or not CPTP. The numerical results for the bias of under-mitigated and over-mitigated errors are shown in Fig. 4. For the under-mitigated error, \({\widehat{\lambda }}_{i}^{(j)}\le {\lambda }_{i}^{(j)}\), we have \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})=1\), as shown in Fig. 4c, and the upper bound is shown in Fig. 4a as

where Δλ = ∑iΔλi > 0. For the over-mitigated error, \({\widehat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is not CPTP as illustrated in Fig. 4c, the upper bound increases as the layer number increases, as shown in Fig. 4b

where \(\Delta {\lambda }_{-}\equiv {\sum }_{i}| \min \{\Delta {\lambda }_{i},0\}|\). Therefore, when considering the error model violation, the under-mitigated error channel outperforms the under-mitigated error channel.

a, b Colored filling regions denote the bias of expectations for different Pauli operators, and solid curves denote the median of the bias of the operator expectations. Dashed curves denote the distance between the mitigated error \({\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\) characterized by the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{\mathcal{I}}}}-{\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\), which upper bounds the bias of the operator expectations in Eq. (26). Dotted curves denote the CPTP upper bound of \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({{{\mathcal{I}}}}-{\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\), as shown in Eqs. (45) and (46) for the under-mitigated and over-mitigated errors, respectively. The mitigated error channel \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}^{-1}\circ {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}\) for each layer is assumed to be the same, \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{i}={{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{0}\), and randomly sampled from the Pauli-Lindblad error model in Eq. (21), with a fixed single-layer error rate \(\Delta {\lambda }^{{{{\rm{under}}}}}=0.05\Delta {\lambda }_{i}^{{{{\rm{under}}}}}\ge 0\) for the under-mitigated error channel (a), and \(\Delta {\lambda }_{i}^{{{{\rm{over}}}}}=-\Delta {\lambda }_{i}^{{{{\rm{under}}}}}\) for over-mitigated error channel (b). c Dotted dashed curves denote the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}}({\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}})\) for the under-mitigated and over-mitigated errors. Since the under-mitigated error \({\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is CPTP, the bias is lower than the CPTP upper bound as shown in (a). In contrast, the over-mitigated error channel \({\hat{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}}^{-1}\circ {{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is not CPTP, the bias increases exponentially as the layer number L grows, which is bounded by the non-CPTP upper bound in Eq. (46) as shown in (b). For details of simulation, see Supplementary Note VI.

For the error beyond the description with the Pauli diagonal error model, it can be randomly compiled into the Pauli diagonal error model by using the well-performed Pauli twirling technique. However, when the number N of shots for Pauli twirling is not sufficiently large, the inaccurate error model will yield a deviation from the estimation. This deviation will be suppressed with the increase of N as \(\sim \! 1/\sqrt{N}\) according to the large number theorem, so it can be interpreted as a statistical error of the estimation. Given a tolerant precision δ of the estimation and a tolerant probability γ ≪ 1 for the failure, the number of shots N should satisfies

where A, B ≥ 0 are constants for the specific error model. More detailed discussions can be found in Supplementary Note V.

Discussion

The implementability function is related to several quantities in quantum information theory and has further applications in quantum information processing. Here, we discuss the relationship between the implementability function and the diamond norm, logarithmic negativity, as well as purity. These results can reduce to the results about CPTP operations \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\to A)\) in other works. However, our technique does not stem from the semidefinite property of \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}\) but uses the convexity and the free property of resource theories and can be applied to a general case.

We first consider the relationship between the implementability function and the diamond norm38,40. For a system A, given a convex free set of states \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(A)\), the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}(A)}\) can be defined. Naturally, it induces a norm on the space of quantum operations \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A\to A)\)

This norm is a generalization of the diamond norm

where the free set is \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\otimes A)\), since the implementability function \({p}_{Q(A)}={\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }_{1}\), with respect to the set of all quantum state \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A)\) is the trace norm \({\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }_{1}\) (see Supplementary Note VII). The norm \({\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }_{\diamond{{{\mathcal{F}}}}(A)}\) is the Minkowski functional of the set \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{\max }(A\to A)\) of resource non-generating (RNG) operations2, i.e., the maximal assignment of operations for the free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(A)\) of state (see Supplementary Note VII for the proof)

Therefore, the diamond is the exponential of the physical implementability

This result has also been proved with semidefinite programs41, where \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\to A)}\) is denoted as \({\Vert \cdot \Vert }_{\blacklozenge}\). We give a different proof (see Supplementary Note VII) without semidefinite programs, which is simpler.

In addition, we consider the relationship between the implementability function and the logarithmic negativity. The following results generalize the results of physical implementability22. The logarithmic negativity is defined as42,43

which denotes the negativity of the partial transposed density matrix \({\rho }^{{T}_{B}}\), and is effective to detect entanglement44,45. Since \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(AB)}={\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }_{1}\), it is the logarithm of implementability function

on the free set \({T}_{B}({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})(AB)\) of partial transpose of quantum states, since the partial transpose \({T}_{B}(\rho )={\rho }^{{T}_{B}}\) is a linear involution \({T}_{B}^{2}={{{{\rm{id}}}}}_{B}\). Given a convex free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(AB)\), for ρ ∈ B(AB), we can define a generalized version \({E}_{N{{{\mathcal{F}}}}(AB)}\) of logarithmic negativity with respect to a convex set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(AB)\) as

where \({T}_{B}({{{\mathcal{F}}}})(AB)\) is the partial transpose of the free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}(AB)\). With the so-defined generalized logarithmic negativity and the sub-multiplicity of implementability function, it follows that for \(\rho ={{{\mathcal{N}}}}({\rho }_{0})\), where \({\rho }_{0}\in {{{\mathcal{B}}}}(AB)\), \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\in {{{\mathcal{B}}}}(AB\to AB)\)

where the action of partial transpose on operations is induced as

For the proof, see Supplementary Note VII. This inequality is tight when

and by Eq. (50), i.e., the free set of operations is a resource nongenerating set

When the operation \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) is invariant under the partial transpose, namely

the inequality reduces to

In particular, it holds for the local operations \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}={\sum }_{i}{q}_{i}{{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}^{A}\otimes {{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}_{i}^{B}\), which is invariant under the partial transpose.

Purity is the square of the Frobenius norm \({\left\Vert A\right\Vert }_{2}=\sqrt{{{{\rm{Tr}}}}({A}^{{{\dagger}} }A)}\). Let \(\sigma \in {{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A)\), \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\in {{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A\to A)\). For the Frobenius norm, we have

where \({\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }_{F}\) is an induced norm of the Frobenius norm

where \({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{i}\) is the Jordan decomposition of the operation \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\) as the matrix acting on the vector space of state \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A)\). Here, \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{l}\) is the extreme points of the free set, where \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) has optimal decomposition on them. In particular, if the operation \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}\) is identity, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}(I)=I\), denoting σ = ρ − I/D, we have

Moreover, if \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}={\sum }_{l}{x}_{l}{{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{l}\) is a unitary mixed operation, where the unitaries \({{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{l}\in {{{\mathcal{F}}}}(A\to A)\) are free, namely \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{l}={{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}_{l}\), we have

For the proof, see Supplementary Note VII.

Conclusion

The implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}\) is the generalization of physical implementability to arbitrary convex free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\), which evaluates the minimal cost to simulate a resource with the free resources by quasiprobability decomposition. We investigate the noisy realization of the PEC method based on the properties of the implementability function. We demonstrate the way to optimally simulate the inverse operation of the error channel with the noisy Pauli basis. This method requires that the noisy Pauli gates can be reversed into ideal Pauli gates. We give the condition under which the invertibility is guaranteed with a tolerant probability of failing under finite measurements in experiments. We also derive upper bounds of the bias of the noisy cancellation of error channel without canceling the noise on Pauli gates. It shows that to mitigate the error channels in circuits with many layers, canceling the total error directly has better performance than canceling the layer errors separately when the error rate and layer number are small. Otherwise, the separate cancellation has better performance.

Moreover, we discuss several quantum-information quantities that are relevant to the implementability function, including the diamond norm, logarithmic negativity, and purity. We propose a norm on quantum operations based on a given implementability function of state, which is a generalization of the diamond norm. This norm denotes the implementability function of the resource non-generating set of the operation. It directly implies that the diamond norm is the exponential of physical implementability, which has also been proved with semidefinite programs41. Moreover, we derive the relation between the implementability function and the logarithmic negativity and purity, which extends the existing results22.

Our results are mainly based on the convexity of the free set. However, the composition of the operation may imply more properties for quantifying resources, which may be left to further research. We hope that our results will be useful for the probabilistic error cancellation method in practice. We also expect that the implementability function will have more applications in the field of quantum information processing.

Methods

Let A, B, C, … denote the systems; the Hilbert spaces of these systems are \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{A},{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{B},{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{C}\). The set of bounded linear operators on the Hilbert space \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{A}\) is denoted as \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A)\), to which the density matrices of A system belong. The linear operation on the operators from \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A)\) to \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(B)\) is denoted as \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}(A\to B)\).

The quantum resources form a convex set \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}\subset {{{\mathcal{B}}}}/{\mathbb{R}}\) of space of normalized resources. Here, we focus on the quantum channels \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}(A\to A)\), which are the completely positive and trace preserving (CPTP) quantum operations. For the noisy cancellation, the implementable channels can be expressed as \(\Theta ({{{\mathcal{Q}}}})(A\to A)\), where Θ is the linear map from ideal channels to noisy channels. In this section, the symbol (A → A) for quantum operation will be omitted for simplicity.

The quasiprobability decomposition technique used in the PEC has also been used in other quantum information processing tasks, such as entanglement forging46, where the entangled states are simulated with separable states, and circuit knitting47,48,49, where the nonlocal operations are simulated with local operations. Therefore, it is worth extending the definition of the physical implementability to any convex free set of quantum resources. (see Supplementary Note I for a brief introduction to the framework of quantum resource theories). In general, for a given convex set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) of freely implementable resources, the implementability function can be defined as

over all decomposition N = ∑ixiEi with \({E}_{i}\in {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\). Our definition does not take the logarithm, since the implementability function p(N) so-defined is just the minimal number of free operations used to simulate a resourceful operation with quasiprobability decomposition technique. Meanwhile, this quantity is also related to the robustness measure R in the quantum resource theories2,10,50,51 as

The robustness depicts the minimal amount of mixing with free resources to wash out all resources51. The implementability function operationally corresponds to the inverse problem of the robustness.

The infimum of the cost is attained if the convex set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) is bounded closed

Hereafter, we assume that the free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) is a bounded closed convex set. Then, the implementability function has the following basic properties:

-

(i)

Faithfulness

$$p(N)\ge 1,\,{{{\rm{and}}}}\,N\in {{{\mathcal{F}}}},\,{{{\rm{iff}}}}\,p(N)=1.$$(68) -

(ii)

Sub-linearity

$$p(a{N}_{1}+b{N}_{2})\le | a| p({N}_{1})+| b| p({N}_{2}).$$(69) -

(iii)

Composition sub-multiplicity

$$p(M\circ N)\le p(M)p(N).$$(70) -

(iv)

Tensor-product sub-multiplicity

$$p(M\otimes N)\le p(M)p(N).$$(71) -

(v)

If \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{1}\subset {{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{2}\),

$${p}_{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{1}}\ge {p}_{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{2}}.$$(72)

In general, not all the resources can be implemented by the resources that can be freely implemented with quasiprobability decomposition. One example is that if the freely implementable resources are local operations and classical channels (LOCC), the CNOT gate is not implementable22. Therefore, we consider the affine space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}={{{\rm{aff}}}}({{{\mathcal{F}}}})\), and the vector space \(V=\langle {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\rangle\) generated by the free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\). Then, the implementability function \({p}_{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}\) is the Minkowski gauge function52 of the convex set \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}={{{\rm{conv}}}}({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\cup -{{{\mathcal{F}}}})\), when constrained on the affine space \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}={{{\rm{aff}}}}({{{\mathcal{F}}}})\), as

This implies that the implementability function is a ratio of the length of lines, which is an affine invariant preserved by affine transformations GA(V)53. In the vector space V, the implementability function is a norm, which is the so-called base norm for the free set \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\)54,55. Actually, for any norm ∥ ⋅ ∥, since its sub linearity, there is a balanced convex set \({{{{\mathcal{C}}}}}_{\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }=\{N:\parallel N\parallel \le 1\}\), such that the norm is the Minkowski gauge function of \({{{{\mathcal{C}}}}}_{\left\Vert \cdot \right\Vert }\). Therefore, the implementability function may be potentially related to many norms widely used in quantum information theory. For the proofs of the properties above, see Supplementary Note II. For more mathematical properties and structures of the implementability function, see Supplementary Note III and Supplementary Note IV.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository56: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29290544.

Code availability

The codes used in numerical simulation have been deposited in the Figshare repository56: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29290544.

References

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum computation and quantum information (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Chitambar, E. & Gour, G. Quantum resource theories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025001 (2019).

Breuer, H.-P. & Petruccione, F. The theory of open quantum systems (Oxford University Press, USA, 2002).

Mohseni, M., Rezakhani, A. T. & Lidar, D. A. Quantum-process tomography: Resource analysis of different strategies. Phys. Rev. A 77, 032322 (2008).

Wigner, E. Group theory: and its application to the quantum mechanics of atomic spectra, Vol. 5 (Elsevier, 2012).

Cai, Z. et al. Quantum error mitigation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045005 (2023).

Temme, K., Bravyi, S. & Gambetta, J. M. Error mitigation for short-depth quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180509 (2017).

Endo, S., Benjamin, S. C. & Li, Y. Practical quantum error mitigation for near-future applications. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031027 (2018).

Cai, Z. Multi-exponential error extrapolation and combining error mitigation techniques for NISQ applications. npj Quantum Inf. 7, 80 (2021).

Takagi, R. Optimal resource cost for error mitigation. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033178 (2021).

Takagi, R., Endo, S., Minagawa, S. & Gu, M. Fundamental limits of quantum error mitigation. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 114 (2022).

Sun, J., Yuan, X., Tsunoda, T., Vedral, V., Benjamin, S. C. & Endo, S. Mitigating realistic noise in practical noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 034026 (2021).

Suzuki, Y., Endo, S., Fujii, K. & Tokunaga, Y. Quantum error mitigation as a universal error reduction technique: Applications from the NISQ to the fault-tolerant quantum computing eras. PRX Quantum 3, 010345 (2022).

Strikis, A., Qin, D., Chen, Y., Benjamin, S. C. & Li, Y. Learning-based quantum error mitigation. PRX Quantum 2, 040330 (2021).

Guo, Y. & Yang, S. Quantum error mitigation via matrix product operators. PRX Quantum 3, 040313 (2022).

Piveteau, C., Sutter, D. & Woerner, S. Quasiprobability decompositions with reduced sampling overhead. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 12 (2022).

Van Den Berg, E., Minev, Z. K., Kandala, A. & Temme, K. Probabilistic error cancellation with sparse Pauli–Lindblad models on noisy quantum processors. Nat. Phys. 19, 1116–1121 (2023).

Pechukas, P. Reduced dynamics need not be completely positive. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1060 (1994).

Carteret, H. A., Terno, D. R. & Życzkowski, K. Dynamics beyond completely positive maps: Some properties and applications. Phys. Rev. A 77, 042113 (2008).

Cai, Z. A practical framework for quantum error mitigation. arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.05389 (2021).

Jiang, J., Wang, K. & Wang, X. Physical implementability of linear maps and its application in error mitigation. Quantum 5, 600 (2021).

Guo, Y. & Yang, S. Noise effects on purity and quantum entanglement in terms of physical implementability. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 11 (2023).

Wallman, J. J. & Emerson, J. Noise tailoring for scalable quantum computation via randomized compiling. Phys. Rev. A 94, 052325 (2016).

Li, Y. & Benjamin, S. C. Efficient variational quantum simulator incorporating active error minimization. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021050 (2017).

Cai, Z. & Benjamin, S. C. Constructing smaller Pauli twirling sets for arbitrary error channels. Sci. Rep. 9, 11281 (2019).

Hashim, A. et al. Randomized compiling for scalable quantum computing on a noisy superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041039 (2021).

Koczor, B. Exponential error suppression for near-term quantum devices. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031057 (2021).

Erhard, A. et al. Characterizing large-scale quantum computers via cycle benchmarking. Nat. Commun. 10, 5347 (2019).

Helsen, J., Roth, I., Onorati, E., Werner, A. & Eisert, J. General framework for randomized benchmarking. PRX Quantum 3, 020357 (2022).

Flammia, S. T. & Wallman, J. J. Efficient estimation of Pauli channels. ACM Trans. Quantum Comput 1, 32 (2020).

Harper, R., Flammia, S. T. & Wallman, J. J. Efficient learning of quantum noise. Nat. Phys. 16, 1184 (2020).

Ferracin, S. et al. Efficiently improving the performance of noisy quantum computers. Quantum 8, 1410 (2024).

Guimarães, J. D., Lim, J., Vasilevskiy, M. I., Huelga, S. F. & Plenio, M. B. Noise-assisted digital quantum simulation of open systems using partial probabilistic error cancellation. PRX Quantum 4, 040329 (2023).

Govia, L. et al. Bounding the systematic error in quantum error mitigation due to model violation, arXiv:2408.10985 (2024).

Zhao, P. et al. Quantum crosstalk analysis for simultaneous gate operations on superconducting qubits. PRX Quantum 3, 020301 (2022).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Zurek, W. Threshold accuracy for quantum computation. arXiv: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.quant-ph/9610011 (1996).

Aharonov, D. & Ben-Or, M. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant error, in https://doi.org/10.1145/258533.258579Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, STOC ’97 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1997).

Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum computations: algorithms and error correction. Russ. Math. Surv. 52, 1191 (1997).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 307 (2015).

Watrous, J. The theory of quantum information (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Regula, B., Takagi, R. & Gu, M. Operational applications of the diamond norm and related measures in quantifying the non-physicality of quantum maps. Quantum 5, 522 (2021).

Vidal, G. & Werner, R. F. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 65, 032314 (2002).

Plenio, M. B. Logarithmic negativity: A full entanglement monotone that is not convex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 090503 (2005).

Peres, A. Separability criterion for density matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1413 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states: necessary and sufficient conditions. Phys. Lett. A 223, 1 (1996).

Eddins, A. et al. Doubling the size of quantum simulators by entanglement forging. PRX Quantum 3, 010309 (2022).

Mitarai, K. & Fujii, K. Constructing a virtual two-qubit gate by sampling single-qubit operations. N. J. Phys. 23, 023021 (2021).

Mitarai, K. & Fujii, K. Overhead for simulating a non-local channel with local channels by quasiprobability sampling. Quantum 5, 388 (2021).

Piveteau, C. & Sutter, D. Circuit knitting with classical communication. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 70, 2734–2745 (2023).

Brandão, F. G. S. L. & Gour, G. Reversible framework for quantum resource theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 070503 (2015).

Vidal, G. & Tarrach, R. Robustness of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 59, 141 (1999).

Osborne, M. S. & Osborne, M. S. Locally convex spaces (Springer, 2014).

Prasolov, V. V. & Tikhomirov, V. M. Geometry, Vol. 200 (American Mathematical Society, 2001).

Hartkämper, A. & Neumann, H. Foundations of Quantum Mechanics and Ordered Linear Spaces: Advanced Study Institute Marburg 1973 (Springer, 1974).

Regula, B. Convex geometry of quantum resource quantification. J. Phys. A 51, 045303 (2017).

Jin, T.-R., Zhang, Y.-R., Xu, K. & Fan, H. Numerical data and codes for “noisy probabilistic error cancellation and generalized physical implementability, Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29290544.v1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0301800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. T2121001, 92265207, 12122504, 12475017), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024A1515010398). We also acknowledge the support from the Synergetic Extreme Condition User Facility (SECUF) in Beijing, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.F. and Y.-R.Z. supervised the project; T.-R.J. proposed the idea; T.-R.J. performed the numerical simulations and discussed with Y.-R.Z. and K.X.; T.-R.J., Y.-R.Z. and H.F. co-wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the discussions of the results and development of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Luke Govia and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, TR., Zhang, YR., Xu, K. et al. Noisy probabilistic error cancellation and generalized physical implementability. Commun Phys 8, 296 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02217-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02217-8