Abstract

Since the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, there has been a growing interest in localizing SDGs through co-designed and participatory approaches. However, the implementation of SDGs in Arctic towns and cities has been the subject of limited research. The unique environmental, economic, and social conditions of these cities raise questions about the suitability of applying generalized approaches and indicators. To shed light on the unique challenges faced by Arctic cities and to gain insight into local urban development professionals’ perspectives and priorities regarding sustainable urban development, we employed a multidisciplinary approach based on Q-methodology. We focus on towns and cities in the Nordic plus Greenland Arctic. The results reveal seven distinct factors representing both shared perspectives and areas of disagreement on sustainable development. The findings indicate that tailored approaches are necessary for the successful implementation of the SDGs in Arctic cities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The agglomeration of people and activities in cities stimulates socio-economic development while simultaneously intensifying greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions1. Cities play a crucial role in addressing climate change and sustainability challenges as they are home to a significant portion of the global population (56%), act as a major driver of the global economy (80% of global GDP), account for a significant share of energy and resource consumption (60–80% of energy consumption), and 70% of anthropogenic carbon emissions2,3 (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview). Recognizing the crucial role of cities in sustainability, the United Nations adopted in 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These 17 goals provide a universal framework to address global challenges such as poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, and climate change, promoting a balance between economic growth, social inclusion, and ecological preservation4. By 2050, the urban population is anticipated to exceed 68% globally5. From an urban planning point of view, while the SDGs offer an overarching (global) roadmap for sustainable development, their implementation at the city level requires localized strategies that align with unique context-specific conditions. Many cities apply participatory approaches to integrate SDGs into urban policies related to sustainable mobility, renewable energy, waste management, and housing6,7. To solve the core issues of sustainability, it is important to understand and address the existing contextual challenges and link them to the global SDGs8,9. This helps ensure that investments support sustainable development rather than achieving short-term goals8. All in all, critiques highlight the inadequacy of existing methods and indicators to reflect local contexts, limited data availability, and an overemphasis on outcomes without adequate focus on the processes required to achieve these goals10,11. These challenges show the need for context-sensitive frameworks for urban sustainability.

Cities located in the Arctic region are an extraordinary example of the need to tailor SDGs to specific local contexts. Arctic cities have a long history of resilience and adaptation, using local knowledge and materials to develop innovative ways to adapt to harsh climate conditions. For example, structures like the ‘Krenkku’ (a traditional wooden bridge used to fish with a net) in the Swedish Arctic demonstrate the use of natural materials and adaptive construction techniques suited to the Arctic riverine landscape12. However, modern Arctic cities face increasing pressures as conventional urban planning approaches, often influenced by southern standards and technologies, struggle to accommodate Arctic conditions. The reliance on resource extraction and energy-intensive industries has further increased per capita energy consumption, highlighting the need for adaptive, region-specific solutions that consider factors such as permafrost, extreme weather, and seasonal variability13. For instance, Sweden’s Norrbotten region, one of our main case studies in this research, has the highest per capita energy consumption in the country (despite having the lowest population density), reaching 131.73 kWh per person. This is significantly higher than the second-highest region, Västra Götaland, which has a per capita consumption of 38.47 kWh (https://arcg.is/1a491C2). These trends highlight the critical need for tailored sustainability frameworks that balance development and environmental preservation. While the Arctic’s unique challenges demand localized approaches, the lack of contextual knowledge and participatory processes often hinders the effective implementation of SDGs14,15. A notable example is the relocation of the city center in the mining city of Kiruna in Sweden— initially framed as an opportunity to build a sustainable smart city16— which ultimately became a missed opportunity to build a carbon-neutral city, as the client and city planners opted for a more business-as-usual scenario17.

The unique environmental, social, and economic conditions of the Arctic are often inadequately addressed by the global SDG framework, highlighting the need for region-specific goals and indicators14. One effort to address this has involved the localization of the ISO 37120 standard— a framework for assessing urban sustainability worldwide18— for Arctic cities, adapting the index to better reflect the distinctive characteristics and priorities of the region11. While ISO 37120 provides a universal benchmark for urban sustainability through a set of general indicators, it does not establish specific targets or offer guidance on what ideal outcomes should look like for each city’s unique cultural or geographical contexts18. This lack of specificity presents challenges for cities seeking to adapt the framework to their unique circumstances. In the Arctic, these limitations are particularly evident, as the standard overlooks critical regional factors such as remoteness, reliance on resource extraction for economic viability, vulnerability to economic fluctuations, and the central role of indigenous communities in shaping local sustainability priorities11. In fact, this index is helpful for global comparisons but not for understanding or solving the specific needs of Arctic communities, as it doesn’t include indicators that reflect the unique challenges and priorities of specific communities19. To address this limitation, modifications have been proposed to incorporate indicators that measure the resilience of Arctic cities, such as dependence on non-renewable resources, links to regional ecosystems, indigenous community involvement, and initiatives to mitigate climate impacts like permafrost melting and coastal degradation11. These adjustments would make the framework more relevant and actionable for Arctic cities striving for sustainability amidst unique environmental and socio-economic pressures. Another study highlights the critical role that the Arctic Council—an intergovernmental forum for Arctic cooperation—can play in formulating a sustainable development framework specifically designed to address the unique needs of the Arctic, given the region’s shared characteristics across its diverse areas20. This framework should prioritize the inclusion of indigenous perspectives and knowledge by revising the current SDGs and introducing five additional goals specific to the Arctic context20. These proposed objectives focus on strengthening the indigenous governance system and rights, preserving cultural knowledge and traditions, protecting the fragile Arctic environment, ensuring equitable access to resources, and fostering intergenerational learning20.

This study attempts to explore local perspectives on sustainable development in cities in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland, highlighting the contextual aspects that influence SDG implementation and revealing the need for localized adaptations. Instead of advocating for a one-size-fits-all model, this study contributes to the development of contextualized sustainability strategies that reflect the unique environmental, economic, and cultural conditions of Arctic cities. To achieve this, we employ Q-methodology, a research approach that effectively captures the diversity of participants’ perspectives, highlighting both areas of consensus and disagreement. This methodology is particularly suitable for analyzing the complexity of subjective viewpoints, as it uncovers the underlying motivations behind sustainability priorities across different participant groups21. By doing so, the Q methodology provides a nuanced understanding of the contextual dynamics shaping sustainable development in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland. Our research question is thus: What are the key perspectives and priorities of local urban development professionals regarding the implementation of sustainable development in cities in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland?

Results

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the Q-sorts resulted in the extraction of eight factors, each with eigenvalues greater than 1. Collectively, these factors accounted for 72% of the total variance, indicating that they represented most of the patterns and shared perspectives within the dataset (Supplementary Table 3). The first factor accounted for the largest share of the variance at 39%, with an eigenvalue of 13.41. The remaining factors had eigenvalues between 2.6 and 1, with explained variances ranging from 8% to 3%, indicating a diminishing but still notable contribution to the overall variance. Following varimax rotation, participants were grouped into factors based on significant factor loadings (p < 0.05), which reflected a strong alignment with the underlying shared perspectives represented by each factor. Supplementary Table 4 presents the rotated factor matrix, highlighting participants significantly associated with each factor (denoted by *) as well as those with weaker, non-significant associations (denoted by “a”). Factor 1 comprised seven participants, three of whom demonstrated significant loadings. Factor 2 included three participants, all of whom exhibited significant loadings. Factor 3 consisted of five participants, with two showing significant loadings, while factor 4 also included five participants, three of whom were significantly loaded. Factor 5 had only one participant, who demonstrated a significant loading. Factor 6 included five participants, with two exhibiting significant loadings, and factor 7 also comprised five participants, of whom two were significantly loaded. Finally, factor 8 included three participants, all of whom demonstrated significant loadings. In Q methodology, a factor is considered acceptable if it has at least two Q-sorts with significant loadings22. As factor 5 represented only a single participant, it was excluded from further analysis. Consequently, seven factors (factors 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8) were retained, with factors 6, 7, and 8 renamed as factors 5, 6, and 7, respectively, each representing a distinct perspective and priority among the participants. The factors were named based on the relative ranking of positive and negative statements in each factor array, with the highest-ranked statements representing the key themes and perspectives of the factor and the lowest-ranked statements highlighting the less prioritized aspects, ensuring a comprehensive interpretation of the shared viewpoints within each group. Figures 1–7 illustrate the distinguishing statements for factors 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7, respectively, highlighting the unique perspectives and defining characteristics of each factor.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 1 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 1, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps two key statements: G11: Investing in sustainable transportation and infrastructure is essential for connecting remote Arctic communities (blue line) and E3: Arctic cities should develop more diversified economies to reduce reliance on a single sector (red line). The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 1 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 1 places strong emphasis on G11, as indicated by its high Q-sort value (5). This suggests that sustainable transportation and infrastructure investment are a defining concern for this factor. In contrast, E3 receives a much lower Q-sort value (1), implying that economic diversification is not a central priority for Factor 1. The radar chart visually captures how these statements are weighted across different factors, with Factor 6 showing the strongest support for economic diversification (E3).

Distinguishing statements of Factor 2 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 2, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps eight key statements: G1: More investment in infrastructure systems (e.g., transportation, energy, buildings, water systems, etc.) is needed in the Arctic (blue line), G4: Housing shortages in Arctic cities present an urgent challenge that needs immediate attention (red line), G16: Air accessibility in Arctic cities must be enhanced for better connectivity (yellow line), E9: Tourism in the Arctic should be dramatically expanded and encouraged to boost the economy (green line), I5: Capacity building and knowledge-sharing are essential for overcoming sustainability challenges in the Arctic cities (purple line), E2: Resource extraction in Arctic regions requires stricter regulation to protect the environment (pale blue line), C13: Improve gender equality in Arctic cities should be prioritized for fostering inclusive and equitable communities (grey line), and E8: The tourism industry in the Arctic should be carefully regulated to prevent environmental harm (black line). The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 2 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 2 places strong emphasis on G1, as indicated by its high Q-sort values (6). This indicates a strong belief that improving transportation, energy, and water systems is critical for Arctic development. Housing Shortages (G4) is also a major concern for Factor 2 (Q-sort: 5), marking it as an urgent issue requiring immediate attention. Unlike other factors that viewed G16 negatively, factor 2 valued it positively (Q-sort: 3), reflecting the perspective that improving connectivity is an important priority for this factor. E9 receives a mild positive score (Q-sort: 1), suggesting that Factor 2 sees economic benefits in tourism growth but does not consider it a top priority. However, other factors ranked it negatively, suggesting that Factor 2 stands out in seeing tourism growth as a potential opportunity rather than a concern. In contrast, factor 2 received the lowest score in I5, E2, C13, and E8 (Q-sort: −3, −3, −4, −5, respectively), deprioritizing capacity building, environmental regulations, gender equality, and tourism restrictions.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 3 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 3, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps five key statements: I3: Arctic cities should adopt a ‘glocal’ approach, blending global and local solutions to address unique challenges (pale blue line), E4: Arctic cities should embrace a circular economy (recycling and reusing resources to reduce waste) (red line), G3: Green energy solutions are essential for the future sustainability of Arctic cities (yellow line), E11: Economic growth in Arctic cities should be driven by sustainable resource use and responsible extraction (green line), and E3: Arctic cities should develop more diversified economies to reduce reliance on a single sector (carbon blue). The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 3 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Compared to other factors, Factor 3 places greater emphasis on the ‘glocal’ approach (I3, Q-sort: 2), indicating a stronger preference for blending global and local solutions. In contrast, while all other factors rank E4 (circular economy), G3 (green energy), E11 (sustainable resource use), and E3 (economic diversification) positively, Factor 3 stands out with negative Q-sorts (−1, −1, −1, and −2, respectively). This suggests that Factor 3 is less aligned with sustainability-driven economic strategies and diversification efforts, instead prioritizing localized solutions over broader environmental and economic transitions.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 4 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 4, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps five key statements: E6: Arctic cities should promote the consumption of locally produced goods, E5: Economic development in the Arctic should prioritize the needs and wellbeing of local communities, E11: Economic growth in Arctic cities should be driven by sustainable resource use and responsible extraction, E2:Resource extraction in Arctic regions requires stricter regulation to protect the environment, E12: Balancing economic growth with environmental conservation is vital for the Arctic’s future. The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 3 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 4 shows the strongest support for E6 (promoting locally produced goods), assigning it the highest possible Q-sort value (6), reflecting a strong preference for local economic resilience. It also places significant emphasis on E5 (prioritizing the well-being of local communities) with a high Q-sort of 5, further reinforcing its community-centered outlook. In contrast, E11 (sustainable resource use) receives only moderate support (Q-sort: 1), indicating less emphasis compared to Factors 1, 2, 5, and 6, which ranked it more highly. Additionally, Factor 4 is the second lowest in prioritizing E2 (stricter regulation of resource extraction) and E12 (balancing economic growth with environmental conservation), with Q-sorts of 0 and −1, respectively.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 5 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 5, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps three key statements: E7: Relying on imported products and global markets is more cost-effective for the Arctic, C7: Preserving and promoting cultural diversity and indigenous knowledge is crucial for social sustainability in the Arctic, and C6: Sustainable solutions should be incorporated into the daily lives of Arctic city residents. The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 3 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 5 stands out by placing relatively more emphasis on E7 (reliance on imported products and global markets) with a Q-sort of 0, whereas all other factors assigned strongly negative values. In contrast, Factor 5 places limited importance on C7 (cultural diversity and indigenous knowledge), with a Q-sort of 0, making it the third lowest, following Factors 1 and 2, both of which ranked it at −2. Additionally, Factor 5 ranks C6 (integration of sustainable solutions into daily life) the lowest among all factors, with a Q-sort of −3.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 6 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 6, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps four key statements: E13: Environmental conservation should take precedence over Economic growth in the Arctic, I1:Arctic cities should facilitate collaboration between universities, municipalities, and businesses to achieve sustainability, I3: Arctic cities should adopt a ‘glocal’ approach, blending global and local solutions to address unique challenges, C9: Top-down planning and external expertise should lead urban development in Arctic cities. The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 3 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 6 places strong emphasis on E13 (environmental conservation over economic growth) with a Q-sort of 3, making it the second-highest ranking after Factor 7. In contrast, I1 (collaboration among universities, municipalities, and businesses) is significantly deprioritized, receiving a Q-sort of -2, while all other factors rated it positively. Moreover, Factor 6 assigns the lowest scores to both I3 (glocal approach) and C9 (top-down planning), with Q-sorts of −4 and −6, respectively.

Distinguishing statements of Factor 7 and across other factors. This radar chart illustrates the distinguishing statements for Factor 7, highlighting its unique perspectives relative to other factors. The chart maps three key statements: E13: Environmental conservation should take precedence over Economic growth in the Arctic, E12: Balancing economic growth with environmental conservation is vital for the Arctic’s future, E11: Economic growth in Arctic cities should be driven by sustainable resource use and responsible extraction. The contrasting peaks and troughs in the chart demonstrate how Factor 3 diverges from other factors, reinforcing its distinct perspective within the study. Factor 7 places strong and unequivocal emphasis on E13 (environmental conservation over economic growth), assigning it the highest possible Q-sort of 6, clearly establishing environmental protection as its top priority. In stark contrast, it assigns the lowest Q-sort scores among all factors to both E12 (balancing growth with conservation) and E11 (sustainable resource-based economic growth), with scores of −4 and −5, respectively.

Factor 1: Sustainable urban development with a focus on green infrastructure and renewable energy

Factor 1 accounted for the highest variance among the identified factors, making it the most common viewpoint within the participant groups (Supplementary Table 3). This factor included 20% of the p-set, of whom 71% were affiliated with academia and 29% were professionals. The group was predominantly male (71%) and included individuals spanning two age groups: 43% were under 30, while 57% were between 30 and 50 years old. Participants aligned with this factor advocated strongly for sustainable and responsible urban development as the foundation of Arctic cities’ growth. This perspective prioritized economic activities that adhered to environmental stewardship, as demonstrated by their agreement with statements emphasizing sustainable resource use (E11) and renewable energy transitions (G12). The tension between economic growth and environmental preservation was highlighted by a participant who noted: “How much can we allow progress to cost when thinking about environmental impact? It remains an important discussion.”

Supplementary Table 5 presents the comparative ranking of statements for factor 1, highlighting the highest and lowest-ranked statements that defined this perspective. Sustainable transportation and infrastructure investments (G11) emerged as a defining concern for this group. They placed significant emphasis on affordable, efficient, and environmentally sustainable public transportation systems, highlighting their necessity in sparsely populated Arctic regions. This aligned with their broader focus on robust infrastructure to overcome the challenges of remoteness. Building active transportation infrastructure, such as pedestrian and cycling pathways (G6), was also prioritized as essential for fostering sustainability. From this perspective, advancing green energy solutions (G3), adopting circular economic practices (E4), and implementing climate adaptation strategies (G13) were highlighted as urgent measures. One participant underscored the need for immediate action to address climate change, stating: “…adapting to and mitigating climate change demands urgent actions, and zoning is one key tool to influence. For example, the city of Oulu is now preparing various future scenarios until 2040 and defining how to ensure sustainability in land use planning.”

In contrast, participants placed lower importance on population growth (C5) and air accessibility (G16). Population growth was viewed as less relevant to Arctic cities’ challenges, with one participant asserting: “The discussion should focus on making life less strenuous and more positive for the population we have, rather than prioritizing growth.” Similarly, air accessibility was deemed secondary to achieving sustainable transport solutions, as expressed by a participant: “Transport connections must be sustainable, so better air accessibility is not the right direction.” Besides, while recognizing the broader importance of cultural preservation (C7), bottom-up planning (C10), and indigenous knowledge integration (I8), participants appeared to prioritize systemic environmental and economic strategies over these cultural and governance aspects. The lowest-ranked statement, rejecting the inevitability of fossil fuel reliance (G8), further underscored this group’s strong commitment to transitioning Arctic cities toward a sustainable future and moving away from traditional, unsustainable practices. Although collaboration in Arctic urban development (I4) was valued relatively less, some participants acknowledged its importance, particularly in the context of political and economic integration. One participant emphasized the role of international partnerships, stating: “It is essential to consider the world political situation and promote comprehensive and sustainable transport connections of the cities of the Arctic region.”

Factor 2: Infrastructure and population growth as pillars of Arctic urban development

Factor 2 was characterized by a shared perspective among 9% of the total P-set. This group was composed entirely of individuals affiliated with academia, indicating a strong influence of scholarly viewpoints on the factor’s themes. Women constituted the majority of this group, representing 66% of its members. This factor was predominantly composed of younger individuals, with 67% of participants under the age of 30 and 33% between the ages of 30 and 50. This factor reflected a development-oriented perspective that prioritized investment in infrastructure (G1) and population growth (C5) while advocating for sustainable growth strategies (Supplementary Table 6). In contrast to factor 1, participants in this group emphasized the necessity of population growth, stating, “I believe population growth is needed for both economic and sustainability growth.” They rejected the idea of limiting population growth to protect the environment (C4), instead arguing that growth is essential rather than detrimental. This perspective underscored the importance of addressing critical challenges such as housing shortages (G4), which participants identified as a pressing issue requiring immediate intervention. They also placed significant importance on improving air accessibility (G16). One participant noted that while local transportation within Arctic cities is relatively adequate, there is a strong need for better connectivity to non-Arctic cities. She argued that economic growth in the Arctic will inevitably drive increased travel demands, necessitating advancements in transportation infrastructure. This view reflected the belief that enhanced air accessibility is essential not only for fostering economic opportunities and facilitating resource development but also for integrating Arctic cities into broader regional and global networks, thereby strengthening their overall resilience and growth potential.

Furthermore, this group aligned with the idea of compact urban development (G19) and opposed dispersed urban planning (G20). One participant highlighted this by stating, “The beauty of living in a small Arctic city is that everything is easily accessible and efficient. Time is the most important commodity that we as humans have—dispersed communities are not really in line with that.” This preference for compact urban systems, combined with their rejection of fossil fuel dependence, reflects a forward-thinking approach that aligns with innovation and sustainability goals for Arctic cities. Additionally, participants supported tourism expansion (E9) as a means of economic development. However, they did not prioritize the improvement of gender equality (C13), perceiving it as a less pressing issue. Similarly, they did not emphasize stricter regulations on resource extraction (E2), reflecting a focus on economic and infrastructural growth over environmental regulation.

Factor 3: Balanced development through environmental and social sustainability

Factor 3 comprised 15% of the participant set. The majority (80%) were from academia, while the remaining 20% were professionals with expertise in relevant fields. Notably, all participants in this factor were female. In terms of age distribution, 40% were under 30, while 60% fell within the 30 to 50 age range. This factor represented a perspective that emphasized balancing economic growth with environmental conservation (E12) as vital for the Arctic’s long-term sustainability while integrating social and cultural dimensions (C7) into urban development strategies (Supplementary Table 7). This perspective reflected a holistic understanding of sustainability, encompassing environmental, social, and economic priorities in decision-making processes. Participants strongly believed that Arctic governance must prioritize long-term well-being over short-term economic gains.

Unlike factor 2, participants in this factor rejected the dramatic expansion of tourism (E9), arguing that while tourism can bring benefits, it also poses significant challenges for local communities. Participants emphasized that an increase in tourism is likely to introduce complexities that must be carefully addressed. One respondent noted: “Reading this statement, I immediately thought of ‘last chance tourism,’ which I view critically,” highlighting concerns about the potential strain on local ecosystems and social structures. Instead, participants advocated for stricter regulation of resource extraction (E2) and carefully controlled tourism (E8) to ensure that these industries align with sustainability goals. This viewpoint reflected a strong prioritization of responsible environmental management and social equity in economic activities, distinguishing it from other perspectives, such as factor 2, which emphasized growth over sustainability.

Furthermore, this perspective valued the integration of indigenous knowledge (I8) and cultural diversity (C7) as essential components of social and environmental strategies. One participant articulated that indigenous knowledge, deeply connected to the Arctic environment, could also benefit economic and environmental sustainability, aligning with the belief that local insights are integral to effective governance. This approach complemented the emphasis on partnerships and inclusivity (I1), fostering collaboration between communities, governments, and external stakeholders. One participant highlighted the shared characteristics of Arctic regions across different countries, such as low and dispersed populations, and noted: “Due to the similarities of the regions, knowledge-sharing could significantly reduce the time and resources needed to address the challenges of the area.” This underscores the potential for collective learning and coordinated efforts to enhance sustainability in the Arctic.

Similar to factor 1, this perspective questioned the suitability of the current SDGs for addressing the specific needs of the Arctic (I7). Participants highlighted a shared belief that global sustainability goals must be adapted to fit the Arctic’s distinctive environmental, social, and economic contexts. Participants advocated for tailored approaches that recognized the region’s unique challenges and opportunities, emphasizing the importance of customized strategies to achieve sustainable development outcomes in the Arctic. Community engagement (C1) and the adoption of ‘local’ approaches (I3) reflected the nuanced belief that Arctic sustainability requires a blend of global best practices and locally tailored solutions. This perspective rejected one-size-fits-all approaches to global sustainability goals, emphasizing the Arctic’s unique context and the need for strategies that address its specific challenges. One participant underscored this by stating, “To better achieve the SDGs, it is essential to consider local people’s lived experiences, perceptions, and needs when planning for future attractive cities.” This highlights the importance of integrating local voices into sustainability planning to create more inclusive and effective solutions.

Factor 4: Community-centered development through local resource use and equitable access to services

This factor comprised 15% of the P-set. Of these, 80% were experts in the field, while 20% came from academia. The gender distribution indicated that 80% were female. In terms of age, 20% were under 30, 40% were between 30 and 50, and the remaining 40% were 50 years old or older. This factor reflected a perspective that highlighted the importance of local sustainability and prioritized community needs in Arctic cities (Supplementary Table 8). This viewpoint emphasized empowering local populations, adopting sustainable practices, and addressing the Arctic’s unique challenges through culturally sensitive and localized approaches. Participants aligned with this factor strongly advocated for the promotion of locally produced goods (E6) while rejecting a heavy reliance on imported products (E7). They underscored the belief that reducing dependency on external supply chains is crucial for achieving long-term sustainability in the region.

Participants also placed high importance on economic development that centers on the well-being of local communities (E5), expressing concerns that failing to do so could lead to negative societal consequences and a diminished appeal of the Arctic as a place to live. They emphasized that local communities must have a central role in deciding how natural resources are utilized and ensuring they share the resulting benefits. Additionally, participants highlighted the need to integrate sustainable solutions into residents’ daily lives (C6), stressing that sustainability should be practical, actionable, and embedded in everyday activities. Other notable priorities included ensuring equitable access to education and healthcare (C11) and preserving cultural diversity alongside indigenous knowledge (C7). Participants emphasized the importance of empowering smart healthcare solutions in remote regions (C8) as a critical response to the unique challenges faced by Arctic communities. They highlighted the difficulties posed by the remoteness and limited healthcare accessibility in these areas, emphasizing that technological advancements in healthcare are vital for bridging these gaps.

This factor stood out for ranking certain environmental and climate-focused priorities lower than other factors. Statements advocating for prioritizing climate change adaptation (G2) and reducing GHG emissions (G12) were ranked negatively. While participants did not view these issues as unimportant, the lower rankings suggested a perspective that prioritized immediate, localized sustainability efforts over broader global climate concerns. Investing in electric vehicle infrastructure (G5) was also not considered a priority, as one participant noted: “Focusing on EV infrastructure should be coupled with activities that lower consumption, including reducing the number of new vehicles purchased.” They added that there are “more essential priorities to focus on in the Arctic” than this issue, highlighting a focus on pragmatic, community-centered actions.

Participants in this factor remained largely neutral about environmental conservation (E13), though one noted: “Not considering environmental protection led us to the precarious situation we’re in now, and it needs to change.” Similarly, capacity building and knowledge-sharing (I5) were not viewed as top priorities. However, one participant emphasized their importance, stating: “Due to their remoteness and lower population, Arctic areas do not have all relevant capacities ‘in-house’ to solve all sustainability issues they faced.” Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize capacity building and sharing knowledge to learn from others’ experiences. Like factors 2 and 3, participants in this factor strongly rejected the idea that population growth in Arctic cities should be limited to protect resources (C4). Instead, they advocated for an increased population as essential for attracting investments, improving infrastructure, and supporting a diverse economy. Participants highlighted the need to prepare the Arctic for accommodating climate refugees, emphasizing that population growth is critical to sustaining services such as public transportation, healthcare, and elderly care.

Factor 5: Sustainable, livable urban development

Factor 5 represented 15% of the P-set. Among them, 80% were from academia, while 20% were experts. The group was composed of 60% male and 40% female participants. In terms of age distribution, 60% were under 30 years old, and 40% fell within the 30 to 50 age range. This factor was focused on creating sustainable, attractive, and livable Arctic cities through innovative urban planning (G9), the adaptation of green energy solutions (G3), and promoting well-being and the quality of life for Arctic city inhabitants (G10) (see Supplementary Table 9). Participants believed that creating well-designed, appealing urban environments is essential not only for retaining current residents but also for attracting highly educated professionals to the Arctic. One respondent noted: “the Arctic needs living environments of high quality which will be attractive enough for highly educated people to permanently move to northern Sweden.” This indicates that urban livability is seen as a strategy to combat population decline and create thriving communities. Similar to factor 3, participants saw value in investing in cultural infrastructure (G14) to foster vibrant and inclusive societies that enhance the well-being and overall satisfaction of residents. Besides, participants strongly supported transitioning to renewable energy sources (G12) and adopting circular economy models (E4). One respondent described the circular economy as a “paradigm shift from linear economy to circular one,” emphasizing its alignment with achieving SDGs. Respondents associated with this factor also highlighted the unique vulnerabilities of Arctic cities to climate change, emphasizing the urgent need for climate adaptation and resilient planning (G13). They strongly rejected the notion that high living costs could be seen as opportunities for sustainability (E10). One participant specifically noted that elevated living costs are more likely to drive residents away than to foster sustainability efforts.

Like factor 4, they strongly opposed the idea that population growth in Arctic cities should be limited to protect the environment and resources (C4). They acknowledged the importance of having a larger population in the region, emphasizing that “we need more people in our region to maintain well-functioning societies. Otherwise, we will always be dependent on subventions, shadowed by highly populated areas in southern Sweden.” This perspective highlights the balance between fostering sustainable development and ensuring that the Arctic remains socially and economically viable without overly relying on external support. Furthermore, participants expressed concerns about the inadequacy of existing infrastructure for both public and private transportation (G7), underscoring the urgent need for enhanced railway systems and road networks to improve connectivity and sustainability in Arctic cities. One respondent specifically highlighted the need for “a functioning railway system like the North Botnia Line,” emphasizing the importance of modern, efficient transportation networks. Additionally, improvements to roads and public transport were repeatedly mentioned as critical priorities.

Factor 6: Economic diversification and local empowerment

This factor accounted for 15% of the P-set. Among them, 80% were experts, and 20% were from academia. The group was predominantly female, with 80% women and 20% men. All participants fell within the 30 to 50 age range. Participants in this factor emphasized economic resilience in the Arctic by promoting diversification (E3) and fostering community-driven development through local governance. They emphasized bottom-up planning (C10) and incorporating local and traditional knowledge (I8), arguing that strategic urban planning should be guided by these insights (Supplementary Table 10). One participant explained that “local knowledge should be the base for decisions made at the upper level,” underscoring the importance of aligning governance with the lived experiences of Arctic residents. Indigenous communities were also seen as key contributors to sustainable living, offering unparalleled expertise on adapting to Arctic conditions. As one participant noted, “Indigenous communities are the best source of knowledge for sustainable living.” In contrast, top-down planning and reliance on external expertise (C9) were criticized for often lacking a deep understanding of the local environment and the realities of Arctic life. Participants argued that solutions imposed from outside frequently fail to account for the unique challenges of the region, making local involvement essential for effective and sustainable urban development. Similarly, participants expressed strong disagreement with relying on imported products (E7), advocating instead for self-sufficiency and local production to reduce dependency on global supply chains.

Furthermore, participants highlighted the importance of moving beyond reliance on a single industry, such as resource extraction (E2), to create a more resilient and sustainable economy in Arctic cities. One participant noted: “When a region is dependent on one sector, it affects many parts of society… social sustainability is diminished when work diversity decreases.” They argued that a diversified economy benefits both people and the environment. Moreover, concerns were raised about the risks of large-scale mining, particularly by multinational corporations, which may harm both the environment and indigenous rights. Another participant emphasized that “mining projects disrupt the sensitive northern environment and cause irreversible damage,” urging caution in extraction activities to avoid further harm to both natural landscapes and indigenous communities, whose promised benefits often fail to materialize. Participants concluded that ‘resources are finite’, and their extraction must be strictly regulated to avoid damaging the Arctic’s delicate ecosystem. Similar to factor 1, participants in this factor assigned a very low ranking to improve air accessibility in the Arctic (G16). They also placed less emphasis on adopting a glocal approach (I3) and facilitating collaboration between different sectors (I1) compared to other factors.

Factor 7: Environmental sustainability and conservation prioritization

Factor 7 consisted of 9% of the p-set, with 67% representing academia and 33% from the expert group. All participants were female, with 33% aged below 30 and 67% aged between 30 and 50. This factor centered around the strong preference for prioritizing environmental sustainability over economic growth (E13) (see Supplementary Table 11). Participants aligned with this view recognized that unchecked economic growth is often a significant driver of environmental degradation and social issues. A participant highlighted the importance of pursuing sustainability goals in a balanced manner, stating that while economic activity has its place, its scale should align with principles of environmental conservation, the well-being of people, and climate resilience. Besides, rather than focusing on fostering a large, globalized economy, the emphasis should be on resilience—both to climate change (G2) and within local communities. As one respondent explained, the priority should be to “sustain the local population first”, ensuring their needs and well-being are met. Only then should we consider sharing resources or opportunities with the global population. Another participant added that “the Arctic should not be a place exploited solely to meet global demands. We need to think locally and prioritize the needs of the people who already live here.” This vision calls for a paradigm shift, focusing on sustainable practices and local well-being (G10) over the pursuit of unchecked economic growth.

This vision also emphasized the necessity of limiting harmful industries, particularly resource extraction (E2), and transitioning toward sustainable energy sources (G3) to safeguard the Arctic’s delicate ecosystems. As one respondent noted, “Global superpowers are circling the Arctic like vultures, waiting for climate change to melt the ice so they can go in and fight over resources. That is why newly available resource extraction in the Arctic needs to be strictly regulated.” The rejection of prioritizing resource extraction to improve the economy (E1) was a key aspect of this viewpoint. Participants highlighted the environmental risks and questioned the long-term social or economic benefits of such activities. One participant asserted that “resource extraction can lead to environmental problems and may fail to address broader social or economic issues in the long term. Instead, we should focus on sustainability goals, such as reusing, recycling, and repurposing materials already extracted from the earth.” The rejection of the idea that economic growth should rely on responsible resource extraction (E11) underscores a belief that, instead of prioritizing new extraction, efforts should focus on more effective utilization of existing materials, as one participant emphasized.

Discussion

Our research aimed to answer the question: What are the key perspectives and priorities of local Arctic urban development professionals regarding the implementation of SDGs in Arctic cities? The results identified seven distinct factors, each reflecting different priorities and viewpoints on SDGs implementation and sustainable development in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland (see Table 1). These findings highlight the complexity of sustainability in Arctic cities and emphasize the need for localized approaches to implementing SDGs, as previous studies suggest that global frameworks often fail to capture the unique socio-economic and environmental challenges of the region11,14.

The first factor advocates for sustainable development through green infrastructure and renewable energy, emphasizing climate adaptation and mitigation as a key priority for sustainable development in the study area. Participants aligning with this factor argue that sustainable urban development can be achieved by integrating active mobility, circular economy, and green energy solutions, prioritizing adaptation as being just as urgent and crucial as reducing GHG emissions. This factor establishes a seeming role of climate action, such as green energy solutions, circular economy, and sustainable infrastructure in achieving the SDGs in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland. This finding is consistent with previous research on the role of climate action in achieving the SDGs and the nexus between climate change and sustainable development23. However, moving forward, greater emphasis should be placed on integrating indigenous knowledge and promoting sustainable governance. These governance approaches are essential for promoting inclusive development, ensuring environmental justice, and guaranteeing that no one is left behind in implementing the 2030 Agenda24.

The second factor highlights population growth and infrastructure investment as critical elements to guide pathways to sustainable development in Arctic cities. The emphasis of this group highlights the nexus between population growth, infrastructure investment, and urban vitality25. Here, participants stress that while population growth is necessary, it should keep pace with infrastructure development. Consequently, investing in housing and transportation, alongside a shift toward more compact urban planning, is seen as vital for expanding economic opportunities and ensuring sustainable growth. The third factor prioritizes balancing economic growth with environmental and social sustainability. As cities are the hub of economic development and play a significant role in climate change mitigation, sustainable development in Arctic cities should consider decoupling economic growth from carbon emissions. This notion aligns with the widely supported perspective that economic decoupling plays a crucial role in achieving the SDGs26, although debates remain on the extent and feasibility of fully decoupling economic growth from environmental impact. Past studies have shown that improved production efficiency and consumption changes significantly contribute to the achievement of SDGs27. For instance, increased consumption patterns stimulate production, resulting in resource depletion, ecosystem degradation, and climate change. Therefore, it is essential to balance economic growth with environmental and social sustainability, as the quest for economic expansion to meet human needs can negatively impact sustainability and the achievement of the SDGs28. Additionally, this factor appears to reflect a common understanding of the pillars of sustainability29, as the participants consider environmental, social, and economic principles vital for achieving the SDGs in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland.

The fourth factor perceives sustainable development in Arctic cities as reliant on community-based development, emphasizing local resource use and equitable access to services. This factor highlights the dilemma in international trade and its connection to sustainability. Participants supporting this factor stress the belief that local sourcing is essential for achieving long-term sustainable development compared to international sourcing, which often prioritizes economic performance at the expense of sustainability30. For example, local sourcing of goods and services shortens supply chains, creates local jobs, and stimulates the local economy while significantly reducing transportation times and environmental impacts. Research has established the connections between international trade and the SDGs. However, contrary to the views of participants aligned with factor four, some research suggests that international sourcing may better support the achievements of the SDGs in developed countries31, such as those in the Nordic Arctic. The fifth factor defines sustainability in the study area as guaranteeing livable urban development. Ultimately, sustainable development in the region should be concerned with leveraging innovative urban planning solutions, green energy transitions, and ensuring quality of life. Additionally, this group prioritizes population growth for sustainable development in the study area. Here, the perception is based on the common notion that population growth is necessary for the economic viability of cities in high-income countries, as has been previously asserted32.

Factor six is consistent with the growing opinion on empowering local communities and diversifying local economies to achieve the SDGs. While community empowerment ensures no one is left behind33, diversifying local economies broadens the range of economic activities within urban sectors and empowers communities to access decent work and economic growth (SDG 8)34. This factor advocates for ensuring economic resilience through diversification and including local and traditional knowledge in decision-making. Gender dynamics appear to influence the opinion of this group, with the predominant gender (females) strongly concerned with inclusion and community empowerment. Earlier studies have disclosed gender disparities in efforts to achieve sustainable development35, hence the call for inclusion and empowerment among female participants in the Arctic. Factor seven argues for environmental sustainability and conservation as a conduit for sustainable development in the study area. Similar to the third factor, this group prioritizes environmental sustainability and economic growth balance, stressing local climate resilience and well-being. Another cross-cutting perspective of this factor argues that sustainable development in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland cities should prioritize local economic growth before emphasizing the shared utilization of resources with the global community. While globalization has positive and negative effects on sustainability36, our finding suggests less importance on globalization and prioritizes local residents’ quality of life. This further indicates the significance of localizing SDG implementation, emphasizing context-specific challenges37.

Despite consensus on broad sustainable development issues, participants expressed differing priorities and implementation pathways. There was general agreement on the critical importance of sustainable resource use and transitioning to renewable energy sources, emphasizing the need to reduce GHG emissions and adopt green energy solutions. Participants also highlighted the necessity of economic diversification to reduce reliance on a single sector, such as resource extraction, and advocated for stricter regulation to mitigate environmental harm. Social sustainability was another key concern, with a strong emphasis on preserving and promoting cultural diversity and integrating indigenous knowledge. Additionally, participants stressed the importance of bottom-up planning and incorporating local and traditional knowledge into urban development strategies, ensuring that local communities play a central role in decision-making processes. Equitable access to education and healthcare services, along with the need for comprehensive climate adaptation plans that enhance infrastructure and community resilience, were also highlighted as key concerns.

However, we noticed disagreements on several key issues, reflecting diverse priorities and perspectives. One major point of contention was population growth; while some viewed it as essential for economic viability and sustaining services, others believed that the focus should be on improving the quality of life for the existing residents. Similarly, there was a divide on tourism expansion, with some advocating for its dramatic growth to boost the economy, while others emphasized the need for careful regulation to prevent environmental harm and manage local complexities. Another area of disagreement was air accessibility, where some participants prioritized better connectivity and economic opportunities through enhanced air travel, while others focused on the importance of developing sustainable local transportation solutions. Approaches toward climate change adaptation and mitigation also differed, with varying views on the urgency and specific policy strategies needed. Additionally, tension arose between prioritizing economic growth and environmental conservation, particularly regarding resource extraction. Finally, there were differing views on infrastructure investment priorities, with some participants advocating for sustainable transportation and housing, while others called for broader infrastructure development, including energy and water systems.

These disagreements highlight the complexity of achieving consensus on sustainable development in Arctic cities. They also indicate that while SDG indicators and other indicator frameworks, such as ISO 37120, establish a global standard for urban sustainability, they may not necessarily fully align with the unique priorities and issues of the Arctic region. It can be argued that global sustainability objectives should be modified to accommodate the Arctic’s unique environmental, social, and economic conditions. Incorporating diverse viewpoints can help refine sustainability frameworks by ensuring that sustainability indicators capture the region’s specific challenges and opportunities, leading to more balanced, effective, and context-sensitive policies. The findings reveal the diverse perspectives of Arctic urban development professionals, underscoring the need for localized SDG implementation strategies that reflect the region’s unique socio-economic and environmental contexts. The seven identified factors highlight priorities that global SDG indicators may not fully capture, such as the emphasis on community empowerment, economic diversification, and climate adaptation tailored to Arctic conditions. By aligning these local priorities with relevant SDGs, our research contributes to understanding how global sustainability frameworks can be more effectively localized. These insights offer a foundation for future research on developing Arctic-specific SDG indicators that resonate with local needs and values, ultimately guiding sustainable urban development in the region.

Based on these findings, future research and policy initiatives on Arctic cities should focus on developing tailored, context-specific frameworks that address the region’s unique environmental, social, and economic challenges. It is essential to thoroughly identify and analyze the critical factors that play a significant role in promoting sustainable development in the region while also examining the complex interactions between them, as they can greatly influence outcomes. In this regard, efforts should be made to create measurable indicators that reflect the Arctic’s distinct conditions. Future research should explore the integration of indigenous knowledge and local perspectives into urban planning and governance, ensuring that development strategies are inclusive and culturally sensitive. Further studies should also investigate the long-term impacts of population growth and tourism on Arctic communities, aiming to find sustainable models that support economic viability without compromising environmental integrity. Strengthening collaboration between Arctic cities—both within the Nordic and beyond— alongside international partnerships can facilitate knowledge-sharing and the adoption of best practices. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach that combines scientific research, local insights and expertise, and innovative policy solutions is essential for achieving the SDGs in Arctic cities.

Methods

This study adopted the Q-methodology to identify the viewpoints and perspectives of urban development professionals on the implementation of the SDGs in the Nordic Arctic and Greenland38. The Q-methodology is a mixed-method approach that allows the collection and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data. It has been used frequently to identify varied opinions and views on complex and multifaceted topics. It has played a significant role in developing pathways for urban development across various cities in developed and developing countries7,39. In imagining the implications of existing development corridors on achieving the SDGs, a study adopted the Q-methodology to understand the possible interactions between SDGs and different development contexts in East Africa40.

The Q-methodology presents a typical five-step approach to selecting a broad range of opinions on a particular topic and identifying diverse participants to rank the opinions based on their subjective viewpoints and perspectives. These viewpoints and perspectives can then be grouped and analyzed to highlight the dominant issues within the topic of discussion. Most importantly, this methodology ensures robustness in assessing and understanding the perspectives and ideas of individuals by allowing the triangulation of both quantitative and qualitative results, unlike methods that use only quantitative or qualitative approaches41. The subsequent sub-sections explain the five-step approach of the Q-methodology used in this study.

Developing the concourse

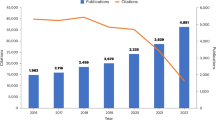

The study developed the initial concourse based on data from primary and secondary sources. The concourse development is a significant step in generating a sample set of statements, ideas, and opinions (Q-sets) to be sorted (Q-sort)7,42. For primary data, we conducted an online survey targeting a purposive sample of sustainability researchers (including those from architecture, geography, social science, and humanities departments). Participants included those affiliated with Luleå University of Technology, Umeå University, the Arctic University of Norway (UiT), the University of Lapland, and the University of Oulu. We also targeted fellows from the Arctic Five Fellows Initiative since the program promotes knowledge sharing to advance research, innovation, and education for a sustainable Arctic (https://www.uarctic.org/news/2023/2/open-call-arctic-five-fellows/). A total of 19 responses were gathered between November 1 and November 10, 2023. Additionally, a literature review was conducted to collect secondary data on the urban sustainability of the Arctic region. The review focused on challenges and potential drivers for achieving and sustaining the gains made in the sustainability agenda within the Arctic region. Consequently, we conducted a review of both peer-reviewed (Supplementary Fig. 1) and gray literature. The gray literature contained urban development reports, government sustainability initiative reports, conference proceedings, and newspaper and media articles. We combined the insights from the literature review with the data from the survey to develop a list of initial statements that constitute the concourse. The combination of primary and secondary sources is to ensure a broad basis of ideas, opinions, and viewpoints to generate a comprehensive Q-set43.

Generating the Q-set

A three-step approach was adopted to generate and categorize the final Q-set. First, we refined the concourse statements to remove redundancies and to ensure a more focused and cohesive Q-set. The Q-set was then validated through a pilot study with 10 master’s students enrolled in a sustainable urban development course at Luleå University of Technology. Feedback from the pilot study was used to review, update, and clarify certain statements and improve the survey format, ensuring the Q-set’s comprehensiveness and relevance for the main study. Eventually, this process yielded a final set of 54 statements for the analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Lastly, we categorized the final Q-set across key urban sustainability dimensions relevant to the Arctic region. This categorization was intended to ensure that the opinions and viewpoints of the participants reflect the complexities and nuances of sustainability issues in the study area. Previous studies have outlined six major themes in Arctic urban sustainability: climate change and adaptation, SDGs and smart urban planning, sustainable development and urban governance, sustainable economic development, social sustainability, and green energy transition44. Building on this framework, we synthesized and refined these themes into four broader categories— Economic Development and Diversification (E), Gray and Green Infrastructure and Environmental Resilience (G), Community and Social Inclusivity (C), and Institutional and Governance (I), to provide a more focused lens for analyzing sustainability priorities in the Arctic context.

P-set identification

A common procedure in a Q-methodology study is identifying participants (P-set) after generating the Q-set39. The P-set involves diverse individuals who participate in the sorting of the Q-set based on their subjective opinions and viewpoints on the topic45. The procedure of selecting the P-set largely demands a purposive sampling approach to involve relevant and opinionated individuals with theoretical and/or practical experience in the topic43. A total of 34 participants, comprising sustainability experts and academic researchers from various Nordic cities, including Luleå, Kiruna, Piteå, Kalix, and Boden (Arctic Sweden), Alta, Bodø, and Mo i Rana (Arctic Norway), Larsmo, Oulu, and Rovaniemi (Arctic Finland), Reykjavík (Iceland), and Nuuk (Greenland) were purposely selected for this study. Supplementary Table 2 shows the P-set characteristics of the study. The sustainability experts involved professionals, municipal urban planners, and project managers. They come from fields such as architecture, urban and spatial planning, strategic planning, social work and education, culture and tourism, regional and community development, business and work strategy, circular economy, waste management, renewable energy, financial markets, and climate risk. Also, the academic researchers comprise senior lecturers, professors, master’s students, PhD and post-doc candidates. They specialize in areas including architecture and urban planning, regional development, sustainable economic and environmental policy, sustainable urban development, human geography, natural resource management, environmental sustainability, consumption-based carbon footprints, traffic planning and winter maintenance, climate adaptation, mobility and well-being, and social science.

Participants specializing in urban sustainability within the study area were identified and invited through targeted searches on municipal websites, LinkedIn, and other social media platforms. We purposely selected these participants to ensure a diverse and comprehensive representation of ideas and perspectives on Arctic urban sustainability and to highlight the similarities and differences in their viewpoints. The participants had a range of familiarity with the subject matter, as 56% reported actively working in the field of urban sustainability in the Arctic region (Supplementary Table 2). More than a quarter (26%) of participants indicated that they possess adequate knowledge of urban sustainability issues in the Arctic through research and learning. 18% reported limited awareness, primarily based on hearing about the topic through sources such as workshops, community capacity-building initiatives, and media. Notably, no participants reported having no knowledge of the subject. Including this diverse group of participants allowed us to capture a broader spectrum of perspectives on sustainability challenges and opportunities in the Arctic. Many of the participants are in the fields of urban and regional planning (26%) and sustainable development and policy (41%). The age distribution of the participants indicates greater representation among younger and middle-aged individuals, with 38% of respondents being below 30 years, 56% falling within the 30–50-year range, and only 6% of participants above 50 years, suggesting a predominance of younger professionals in the study. As we aim to understand people’s priorities for the future in the context of Arctic sustainability, including a higher proportion of younger participants ensures they bring a forward-looking perspective that aligns with their vested interest in shaping sustainable development for the region.

Q-sorting

The Q-sort involves a process of rank-ordering the Q-sets by the identified P-set. During the Q-sort process, the individual P-sets are asked to rank the Q-sets on a predefined Q-grid (see Fig. 8) based on their viewpoints and perspectives on the topic43. The grid is designed to range from -6 to +6, allowing participants to rank statements by placing those they strongly agree with or find highly relevant further to the right, those they strongly disagree with or find less relevant to the left, and neutral statements near the center, enabling a prioritized and nuanced understanding of their viewpoints. In this study, the Q-sort process began with a physical workshop at the MIRAI 2.0 Research and Innovation (R&I) Week held at Umeå University on November 15, 2023. The MIRAI event is a Sweden-Japan collaborative initiative that brings together researchers and professionals from both countries, including those based in the Arctic and non-Arctic regions of Sweden. The Q-sort workshop engaged participants from both Japan and Sweden, facilitating a broader deliberation and discourse on urban sustainability. However, to maintain the geographic and thematic focus of the study, the final Q-sort data were exclusively drawn from participants based in Arctic Sweden. This approach ensures that the analysis accurately reflects the perspectives and expertise of individuals with direct theoretical and/or practical experience in the subject matter within the study area. On 18th September 2024, another physical workshop was conducted with master’s students from the sustainable urban development course at Luleå University of Technology. In addition to the physical workshops, the Q-sorting process also involved two online approaches. First, we conducted an online workshop in November 2023, purposely selecting sustainability professionals working with municipalities in the study area. Then, the Q-set was sent via email to sustainability professionals who showed interest in the study but failed to participate in the online workshop due to reasons including scheduling conflicts, availability, and short notice. To facilitate participation, we provided a short instructional video demonstrating how to complete the survey. Throughout this process, many emails were exchanged to guide participants on the Q-sorting, and sometimes, short meetings were held at participants’ requests to clarify any uncertainties regarding the process. The participants were also asked to answer open-ended questions after the Q-sorting. This was to explore participants’ reasoning behind ranking certain statements as more or less important.

Forced distribution Q-grid for participant ranking. This grid spans from −6 to +6, allowing participants to place statements they strongly agree with or find highly relevant towards the right, and those they strongly disagree with or find less relevant towards the left. Neutral statements are positioned near the center. This arrangement facilitates a detailed and prioritized understanding of each participant’s perspectives.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed to ascertain the opinions and viewpoints of the participants on implementing the SDGs in cities across the Nordic Arctic and Greenland. A factor analysis was performed using the KADE software (v1.2.1) to identify participants with similar viewpoints on the topic. The KADE software, a desktop application for Q methodology data analysis, provides a variety of features not available in similar open-source platforms46. Accordingly, a factor matrix, highlighting trends in agreements and disagreements among participant viewpoints, was extracted using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the KADE software. The Varimax method was used to perform a factor rotation of the matrix, resulting in simplifying the interpretation of the factors. Next, we used the KADE application to perform factor loadings to identify associations between each participant’s Q-sort and identified factors. The final factors were then selected by integrating the quantitative results from the Q-sort and the qualitative data from the post-sort interview39. Thus, we included factors that obtained an eigenvalue of >1, have at least two statistically significant loadings of individual Q-sorts, and a cumulative variance of > 30%47. Additionally, we ensured that the individual Q-sort scores in the selected factors were consistent with data from the post-sort interviews. This allowed for better generalization and reliability of the selected factors39. The factors were then named and interpreted using the Crib Sheet Technique47. The technique allowed for the factors to be named and interpreted based on their statement rank position across different selected factors, ensuring that the most important issues are identified according to the individual Q-sort and the polarization of the factors.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Crippa, M. et al. Global anthropogenic emissions in urban areas: Patterns, trends, and challenges. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 1–15 (2021).

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). The Strategic Plan 2020–2023. UNDP. (2020).

Leavesley, A., Trundle, A. & Oke, C. Cities and the SDGs: Realities and possibilities of local engagement in global frameworks. Ambio 51, 1416–1432 (2022).

United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (United Nations, 2019).

Blasi, S., Ganzaroli, A. & De Noni, I. Smartening sustainable development in cities: Strengthening the theoretical linkage between smart cities and SDGs. Sustain Cities Soc. 80, 1–15 (2022).

Sharifi, A., Dacosta Aboagye, P., Zhang, M. & Murayama, A. A participatory foresight approach to envisioning post-pandemic urban development pathways in Tokyo. Habitat Int. 149, 1–11 (2024).

Leal Filho, W. et al. Using the sustainable development goals towards a better understanding of sustainability challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 26, 179–190 (2019).

Krantz, V. & Gustafsson, S. Localizing the sustainable development goals through an integrated approach in municipalities: early experiences from a Swedish forerunner. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 64, 2641–2660 (2021).

Tiwari, G., Chauhan, S. S. & Varma, R. Challenges of localizing sustainable development goals in small cities: Research to action. IATSS Res. 45, 3–11 (2021).

Berman, M. & Orttung, R. W. Measuring progress toward urban sustainability: Do global measures work for arctic cities? Sustainability 12, 1–15 (2020).

Tornieri, S., Ma, J. & Rizzo, A. Which urban and landscape qualities make Arctic villages attractive? The Torne River villages in Sweden. Eur. Plan. Stud. 32, 1731–1751 (2024).

Garbis, Z. et al. Governing the green economy in the Arctic. Climate Change 176, 1–23 (2023).

Nilsson, A. E. & Larsen, J. N. Making regional sense of global sustainable development indicators for the Arctic. Sustainability 12, 1–20 (2020).

Ma, J. & Rizzo, A. “Arctic-tecture”: Teaching Sustainable Urban Planning and Architecture for Ordinary Arctic Cities. Urban Plan. 9, 1–18 (2024).

Ebrahimabadi, S., Johansson, C., Rizzo, A. & Nilsson, K. Microclimate assessment method for urban design – A case study in subarctic climate. Urban Des. Int. 23, 116–131 (2018).

Rizzo, A., Sjöholm, J. & Luciani, A. Smart(en)ing the Arctic city? The cases of Kiruna and Malmberget in Sweden. Eur. Plan. Stud. 32, 59–77 (2024).

Moschen, S. A., Macke, J., Bebber, S. & Benetti Correa da Silva, M. Sustainable development of communities: ISO 37120 and UN goals. Int. J. Sustainability High. Educ. 20, 887–900 (2019).

Dinapoli, B. & Jull, M. Evaluating plans for sustainable development in Arctic cities. Ambio 53, 1109–1123 (2024).

Degai, T. S. & Petrov, A. N. Rethinking Arctic sustainable development agenda through indigenizing UN sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 28, 518–523 (2021).

Webler, T., Danielson, S. & Tuler, S. Using Q Method to Reveal Social Perspectives in Environmental Research. Greenfield MA: Soc. Environ. Res. Inst. 54, 45 (2009).

Rajé, F. Using Q methodology to develop more perceptive insights on transport and social inclusion. Transp. Policy ((Oxf.)) 14, 467–477 (2007).

Filho, W. L., Wall, T., Salvia, A. L., Dinis, M. A. P. & Mifsud, M. The central role of climate action in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–7 (2023).

Gupta, J. & Vegelin, C. Inclusive development, leaving no one behind, justice and the sustainable development goals. Int Environ. Agreem. 23, 115–121 (2023).

Lan, F., Gong, X., Da, H. & Wen, H. How do population inflow and social infrastructure affect urban vitality? Evidence from 35 large- and medium-sized cities in China. Cities 100, 1–12 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Decoupling environmental impact from economic growth to achieve Sustainable Development Goals in China. J. Environ. Manag. 312, 1–9 (2022).

Han, S. et al. Prospects for global sustainable development through integrating the environmental impacts of economic activities. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–16 (2024).

Lusseau, D. & Mancini, F. Income-based variation in Sustainable Development Goal interaction networks. Nat. Sustain 2, 242–247 (2019).

Garlock, T. M. et al. Environmental, economic, and social sustainability in aquaculture: the aquaculture performance indicators. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–9 (2024).

van Kempen, E. A., Spiliotopoulou, E., Stojanovski, G. & de Leeuw, S. Using life cycle sustainability assessment to trade off sourcing strategies for humanitarian relief items. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 22, 1718–1730 (2017).

Xu, Z. et al. Impacts of international trade on global sustainable development. Nat. Sustain 3, 964–971 (2020).

Peterson, E. W. F. The role of population in economic growth. Sage Open 7, 1–15 (2017).

Tiwari, M. How to Achieve the “Leave No One Behind” Pledge of the SDGs in Newham and Tower Hamlets, East London. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil 22, 748–758 (2021).

Bandari, R., Moallemi, E. A., Lester, R. E., Downie, D. & Bryan, B. A. Prioritising Sustainable Development Goals, characterising interactions, and identifying solutions for local sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 127, 325–336 (2022).

Heggie, C., McKernon, S. L. & Gartshore, L. Gender equity in dentistry in relation to the UN SDG 5. Br. Dent. J. 235, 302–303 (2023).

Mohamed, E. A. S. Globalization, Digitalization, and Sustainable Development Goals: A Roadmap for Equitable Progress. in Developing Digital Inclusion Through Globalization and Digitalization 229–249 (IGI Global, 2024).

Bie, Q. et al. Progress toward Sustainable Development Goals and interlinkages between them in Arctic countries. Heliyon 9, 1–12 (2023).

Carla Willig & Wendy Stainton Rogers. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. (SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017).

Aboagye, P. D. & Sharifi, A. Pathways for future climate action planning in urban Ghana. Habitat Int. 153, 1–22 (2024).