Abstract

While Saharan dust’s influence on sea surface temperature variability in the tropical North Atlantic is well-documented, its effects on the equatorial region remain underexplored. This relationship is particularly important due to the strong influence of equatorial Atlantic variability on both local and remote climates. Here, we use observational and reanalysis data to investigate Saharan dust’s role in boreal winter, a period when dust transport is typically near the equator. A unique footprint of Saharan dust forcing is revealed, as well as a complex, non-monotonic response. Specifically, in contrast to the expected cooling due to shortwave blocking by Saharan dust, lower tropospheric warming, and stabilization lead to a strong sea surface warming off the coast of northwestern Africa and to the development of an off-equatorial warm front. The front drives cross-equatorial winds that induce a northward shift of the Atlantic rain belt, equatorial cooling, and equatorial wave activity leading to delayed equatorial warming. Winter Saharan dust is therefore an important contributor to equatorial Atlantic variability, with cross-regional implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sea surface temperature (SST) fluctuations in the equatorial Atlantic exert a profound influence on regional climate in both local1,2,3 and remote domains4,5,6. This variability arises as a consequence of complex ocean-atmosphere interactions7, often associated with the dynamics in the tropical North Atlantic (TNA)8,9,10,11, which is exposed to vast amounts of Saharan dust transported by the prevailing easterly trade winds12,13,14. Modern climate models do not fully reproduce equatorial Atlantic variability, which strongly limits their ability to represent its multiple associated regional and remote climatic impacts7,15,16. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between Saharan dust and TNA SST, as precursors of equatorial Atlantic variability, is therefore of vital importance.

At interannual time scales, TNA and equatorial Atlantic variability are primarily governed by two modes within the tropical Atlantic, namely, the Atlantic Meridional and Zonal modes (AMM and AZM, respectively). AMM is characterized by an inter-hemispheric gradient of anomalous SST (SSTA), predominantly driven by wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback17. Conversely, the AZM is defined by the zonal SSTA gradient along the equator and is commonly explained by coupled ocean-atmosphere interactions7,18,19,20. Both modes are associated with rainfall shifts that profoundly impact the climate of the tropical Atlantic3,7,21,22,23,24. At interannual timescales, the AMM is generally understood to affect AZM, but not vice versa. This asymmetric relation is attributed, on the one hand, to equatorial wind anomalies related to the latitudinal shifts of the Atlantic Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) that favor transitions from AMM to AZM25, and on the other hand, to ocean processes which include subsurface meridional heat advection19 and heat content adjustment to surface wind variations8,26. In particular, AMM-induced wind-stress anomalies trigger equatorial Rossby and Kelvin waves, shaping the development and decay of AZM, and therefore of equatorial Atlantic variability8,9,11.

The impact of Saharan dust on TNA SST has been extensively investigated, especially in the context of westward dust transport from tropical to the subtropical band during boreal summer and early autumn, known as the ‘northern route’ (up to 35∘N)27. Attention has primarily centered on understanding the relation of the radiative forcing exerted by the dust aerosols in the northern route to Atlantic hurricane activity12,28,29, as well as AMM13. Specifically, scattering and absorption of solar radiation by the dust aerosols cool the ocean surface due to reduced shortwave radiation (SWR), which affects processes related to the upper-ocean heat budget in the TNA12,30. The dust radiative impact, however, is highly dependent on the mineral composition of aerosols and particle size, which are not adequately resolved in current climate models31. Moreover, a statistical analysis found that SWR-blocking by Saharan dust can explain around 35% of interannual SST variability in TNA during boreal summer, but only about 5% when all months are considered12. Indeed, due to the inverse relation of the penetrative component of SWR to mixed layer depth (MLD), the SST response to a dust-related reduction in SWR is significant only in the center of the TNA where the MLD is greater12,32.

The influence of Saharan dust on tropical Atlantic variability cannot be entirely attributed to SWR-blocking alone33,34,35,36,37. Additional influences of Saharan dust may involve its modulation of the thermodynamic properties of the atmospheric column, which can indirectly influence the surface heat balance, for example, by changing cloud properties or by suppressing vertical mixing in the boundary layer31,38,39. Notably, some effects may even induce ocean surface warming, contradicting the direct radiative impact of dust. Some observational studies have shown that SST warming can be driven by longwave heating associated with large dust events37,40. Furthermore, high-resolution and fully coupled models have revealed counteracting effects by altering upper-ocean dynamics through changes in the wind-stress curl41,42. All these findings underscore the complexity of the interaction between dust and ocean heat content, which may have climatic implications for the tropical Atlantic that are still not well understood.

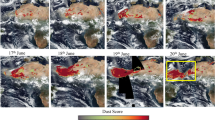

Another route of comparable transport magnitude, known as the ‘southern route’, transports dust towards the Amazon basin over a latitudinal belt between 0∘ and 20∘N during boreal winter and early spring27,43. This route has generally attracted less attention as a potential source of SST variability, and its relation to tropical Atlantic variability, particularly within the equatorial region, remains unexplored. A key distinction between the northern and southern routes is their differing vertical profiles, consisting of larger amounts of desert dust, extending to elevations of approximately 6 km in the northern route, while being concentrated below 2 km altitude and mixed with biomass smoke in the southern route43,44,45,46. Consequently, the radiative and thermodynamic influence of Saharan dust anomalies on the atmosphere can vary between the two routes. Given its distinctive vertical profile and proximity to the equatorial band, this study focuses on assessing the influence of the Saharan dust from the southern route on equatorial Atlantic variability.

To detect the potential impact of dust anomalies associated with the southern route, we perform a lead-lag correlation analysis of Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD) anomalies derived from MERRA2 reanalysis dataset averaged over a defined TNA region ([45∘W–18∘W,0∘–20∘N], black box and black line in Fig. 1a, b), referred to as the DAOD index. This index, fixed in the January-March season (JFM), is correlated with seasonal SSTA averaged over the eastern equatorial ATL3 region ([20∘W-0∘, 3∘S-3∘N]; red box and red line in Fig. 1a), referred to as the ATL3 index7,18,47. Additionally, we examine the association between the DAOD index and seasonal anomalies in the position of the Atlantic ITCZ, which is defined by maximum precipitation48 zonally averaged between 40∘W and 20∘W within the tropical band [20∘S-20∘N]. Interestingly, equatorial SSTA is significantly negatively correlated (R = −0.6) with DAOD anomalies for seasonal lag time scales (two to three months) but are positively correlated with dust anomalies on lag time scales of a year (peaking at about R = 0.4 to 0.5). Similarly, the correlation between DAOD anomalies and northward shifts of the Atlantic ITCZ is positive for about three months following DAOD anomalies (R = 0.6 to 0.4), but then, as in the case of the correlation between DAOD and equatorial SSTA, reverses its sign at about 6 months lag. This non-monotonic relation suggests that radiative and dynamic feedbacks, operating at multiple timescales, link DAOD anomalies and equatorial Atlantic SSTA.

a Regression map of Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD) anomalies onto DAOD index (DAOD monthly anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region [45∘W–18∘W,0∘–20∘N], black box in a, for the period 1994 to 2022) for January–March (JFM) shown for a change of one standard deviation. b Time series of DAOD index and ATL3 index (defined as sea surface temperature anomalies, SSTA, averaged over the ATL3 region [20∘W–0∘, 3∘S–3∘N], red box in a). c Lead-lag correlation of DAOD index fixed in JFM with ATL3 index (red) and latitudinal shifts of the Atlantic Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ; the position of peak precipitation defined as the maximum meridional gradient within 20∘S–20∘N, zonally averaged between 40∘W–20∘W; green). Dashed lines correspond to 90% confidence levels based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

The objective of this study is to identify the underlying processes linking equatorial Atlantic variability and Saharan dust anomalies associated with the winter southern route, as demonstrated above. To this end, we use observational and reanalysis datasets of the atmosphere and ocean. Our findings reveal a chain of mechanisms, initiated by Saharan dust anomalies in the lower troposphere, which have a distinct effect on equatorial Atlantic variability from spring to fall.

Results

Impact of winter Saharan dust on the tropical Atlantic

To first explore the potential impact of the southern route on equatorial Atlantic variability, we conduct a regression map analysis of SSTA, total precipitation, and 10 m wind anomalies from JFM to the following November-January (NDJ), regressed onto the DAOD index averaged over JFM (Fig. 2; see Methods).

a–f Regression maps of seasonal anomalies of sea surface temperature (SSTA; shaded), surface wind (arrows), and total precipitation anomalies ([mm day−1]; green contours) regressed onto the winter (JFM) Dust Aerosol Optical Depth index (DAOD anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region [45∘W–18∘W and 0∘–20∘N] for the period 1994 to 2022). Units are normalized by one standard deviation of the DAOD index. SSTA values at the 90% confidence level based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test are highlighted; precipitation values and wind vectors with confidence level lower than 90% are not shown.

During JFM, strong SST warming develops in the eastern TNA next to West Africa, with maximum anomalies centered at the Senegal coast (around 10∘N; Fig. 2a). The warm anomaly appears concomitantly with an equatorial cooling and anomalous southerly winds over the eastern TNA. The sea surface warming expands south-westward as a warm SST front, centered north of the equator, around 20∘W in March–May (MAM) (Fig. 2b). In response, south-eastern cross-equatorial winds develop, reinforcing the equatorial cooling from MAM to May–July (MJJ) (Fig. 2b, c).

The anomalous SST and associated moisture advection impact tropical Atlantic precipitation. Initially (JFM), negative precipitation anomalies are seen in the eastern equatorial Atlantic over cooler sea surface (green contours, Fig. 2a). Subsequently, precipitation increases westward of the warm front, and decreases south of the equator, extending into Northeastern South America (Fig. 2b, c). This pattern coincides with a northward displacement of the Atlantic ITCZ, in agreement with the positive correlation found with the DAOD index in Fig. 1c, and consistent with previous findings demonstrating ITCZ shifts generated by dust-induced winds and heat fluxes1,49.

From MJJ to NDJ (Fig. 2c–f), the equatorial cold SSTAs dissipate, and an anomalous warm tongue, resembling the winter AZM, develops50. During MJJ and June–September (JAS), the zonal SSTA gradient along the equator begins to reverse its sign, with positive anomalies emerging in the east, over the Gulf of Guinea, and along the South African coast during JAS and September–November (SON) (Fig. 2d, e). From SON to NDJ (Fig. 2d–f) the sea surface warming extends westward, culminating in a warm tongue structure with maximum anomalies over the ATL3 region (red box in Fig. 1a) in NDJ (Fig. 2f). The spatially varying precipitation response during JAS–NDJ is, however, not significant (despite the southward shift of the sector-mean Atlantic ITCZ seen in Fig. 1c). Notice that surface wind anomalies over the equatorial band are also negligible from SON to NDJ (Supplementary Fig. S1) and, therefore, do not influence the underlying SSTAs. Consequently, dust-induced ocean dynamical mechanisms, such as wave propagation, appear as the dominant drivers of equatorial warming during these months7,8,20.

The regression analysis highlights a series of responses that are instigated by Saharan dust anomalies during boreal winter in the tropical Atlantic. First, the DAOD anomaly leads to the emergence of warm SSTAs in the northeastern tropical Atlantic, subsequently giving rise to the formation of a narrow off-equatorial warm front. The front drives cross-equatorial winds, which lead to the development of cold SSTAs along the equator and a northward displacement of the Atlantic ITCZ. Finally, the anomalous cold tongue is disrupted from east to west, and equatorial surface warming emerges in the following winter.

To support the relationships suggested by the regression results we perform a composite analysis using a threshold of one standard deviation of the DAOD index in JFM, with statistical significance evaluated through a Monte Carlo approach (see Methods for further details). Figure 3a, b show the composite maps for years with positive and negative DAOD and associated SST anomalies in JFM, respectively. The spatial SSTA pattern aligns closely with the regression results, showing warm SSTA linked with increased dust load in the eastern TNA (Fig. 3a) and vice-versa (Fig. 3b). Consequently, in addition to the regions associated with the DAOD and ATL3 indexes, we identify a third sector in the eastern TNA [25∘W–18∘W, 5∘N–20∘N], where warm SSTA develop in JFM (purple box in Fig. 3a). This region, characterized by a particularly strong seasonal cycle51, has been previously recognized as a key area within the climatic system of the tropical Atlantic52,53,54. The corresponding composite year of positive events shows warm SSTA peaking at 0.45 °C in February and March (purple solid line in Fig. 3c), aligning with an increase in the DAOD index (black solid line in Fig. 3c). Meanwhile, equatorial SSTA (red solid line in Fig. 3c) shows a cooling trend in spring, reaching −0.3 °C in April in the ATL3 region, followed by a warming trend into the next winter, peaking at 0.2 °C in January. These values correspond to approximately 85% and 57% of the standard deviation of the ATL3 index over the study period, respectively.

a Composite map of sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTA; shaded) and Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD [×10−2]; line contours) during January–March (JFM) for years with positive DAOD index anomalies. b The same as (a), but for negative years. The DAOD index is calculated as the DAOD anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region ([45∘W–18∘W and 0∘–20∘N], black box in a) for the period 1994 to 2022. c Time series of composite years for DAOD index values (black line), SSTA averaged over the eastern TNA ([25∘W–18∘W, 5∘N–20∘N], represented by the purple box in a; purple line), and SSTA averaged over the ATL3 region ([20∘W–0∘, 3∘S–3∘N], represented by the red box in a; red line). Positive composite years are highlighted with solid lines while negative by dashed lines. Data points that are significant at the 95% confidence level, based on a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations, are highlighted with circles.

What drives the dust-induced warm SSTA in the tropical North Atlantic?

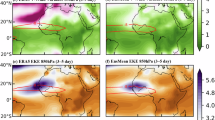

The air mass containing Saharan dust, carried by the trade winds, commonly referred to as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL), coincides with warm atmospheric temperatures associated with shortwave absorbance55,56. Consistent with previous studies the southern-route SAL is observed at the lower troposphere centered at about 920 hPa in the eastern TNA43,46, as seen in Fig. 4a–c, where air temperature is longitudinally averaged over the zonal extent of eastern TNA (dashed purple box in Fig. 4a). The warm anomalies first appear in NDJ (Fig. 4a) and peak in JFM (Fig. 4c).

a–c Regressed anomalous tropospheric temperature (shading), zonal wind ([m s−1]; contours) and normalised zonal Ekman transport (aligned subplot; green line) zonally averaged in the eastern TNA ([25∘W–18∘W, 5∘N–20∘N], purple box in a) over seasonal (3-month) anomalies between November–January (NDJ) and January–March (JFM) onto JFM Dust Aerosol Optical Depth index (DAOD anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region [45∘W–18∘W, 0∘–20∘N] for the period 1994 to 2022). d–f Same as (a–c) but regressed over anomalous 10 m wind-curl maps (negative and positive values are associated with downwelling and upwelling, respectively). Values with a confidence level of 90% or higher based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test are highlighted.

The resulting meridional temperature gradient in the lower troposphere drives northward wind that acquires a geostrophic westerly component, centered at about 950 hPa (contours in Fig. 4a–c), which strengthens with the anomalous temperature gradient. As expanded upon below, the westerly wind anomalies and stabilization of the heated lower troposphere contribute to surface warming by suppressing evaporative cooling. In addition, the changing wind pattern along the western edge of the African coastline leads to a pronounced negative surface wind-curl close to the African coast around 10∘N, indicating coastal downwelling via Ekman pumping, further contributing to the warming of the mixed layer53,57 (green line in lower panels of Fig. 4a–c and contours in d–f). The negative wind curl extends westward to the central Atlantic in JFM (Fig. 4f) following the increasing cross-equatorial winds driven by the development of the meridional SSTA gradient (Fig. 2b, c). This wind curl anomaly near the equator triggers an ocean adjustment via oceanic wave propagation, discussed in the following section.

Assuming that latent heat, shortwave radiation, and Ekman transport dominate the SST variability in the eastern TNA, Fig. 5 illustrates the temporal evolution of these three components contributing to SSTA tendency in response to DAOD anomalies (see Methods). The strong warming is dominated initially by reduced evaporation (downward latent heat flux, LHF, defined as positive) in January between 5∘N and 20∘N (Fig. 5a), in contrast to the cooling by SWR blocking between 12∘N and 20∘N (Fig. 5b). The decrease in evaporation is due to both (i) the westerly wind anomalies, which weaken the prevailing easterly winds, leading to WES feedback mechanism58, as seen in the latitude band 5∘N–15∘N (Fig. 4a–c); and (ii) the stabilization of the lower troposphere due to the tropospheric warming, as seen in the latitude band 10∘N–20∘N (Fig. 4c), which suggest a weakening of vertical turbulent moisture fluxes59.

a–c Time-latitude maps of monthly anomalies of (a) latent heat flux (QLH), (b) anomalous shortwave radiation minus the penetrative component (QSW - Qp), and (c) Ekman heat flux (Qek) in the eastern TNA [25∘W–18∘W, 5∘N–20∘N], regressed onto the January–March (JFM) Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD) index anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region [45∘W–18∘W, 0∘–20∘N] for the period 1994 to 2022. Temperature units are in terms of one standard deviation of the DAOD index. Stippled areas indicate values with 90% confidence or higher based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. d Composite mean of heat contributions for positive years of the DAOD index: shortwave radiation (QSW; blue bar), latent heat flux (QLH; orange bar), and zonal Ekman transport (Qekx; green bar), along with the sea surface temperature anomaly tendency (SSTA; red bar), averaged in the eastern TNA. Significant values based on a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations are marked with a double asterisk for 95% confidence and a single asterisk for 90% confidence. Error bars indicate the standard error of the composite mean. Calculations are based on climatological values of the mixed layer depth in JFM (Supplementary Fig. S2). The negligible contributions of longwave radiation and sensible heat fluxes and residuals are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

In February the SST warming by Ekman heat flux becomes dominant60,61 (Fig. 5c) which aligns with the strong negative wind-curl anomaly along the Senegal coast (Fig. 4f). This wind-driven mechanism is caused by anomalous northward winds, resulting in eastward Ekman transport in the eastern TNA region (lower panels in Fig. 4a–c). Consistent with the regression analysis, the composite mean of the main heat contributions for JFM (Fig. 5d) highlights the dominance of zonal Ekman transport in January and February, while latent heat plays a significant role only in January, and the negative heat contribution from shortwave radiation becomes significant in February and March. Therefore, we conclude that the exceptionally strong SST warming is predominantly driven by Ekman convergence, which is initially reinforced by reduced surface evaporation. This underscores the critical role of wind-induced ocean dynamics in the interaction between dust and SST variability. We next examine the effect of the dust-induced warming in the eastern TNA on equatorial Atlantic variability.

Influence on equatorial SST

Interannual variability in the equatorial Atlantic SST is mainly characterized by zonal SSTA gradient variations (AZM) also commonly referred to as Atlantic Niño/Niña, analogous to its Pacific counterpart. Warm AZM events are typically defined by warm SSTAs and positive sea surface height anomalies (SSHAs) in the eastern equatorial Atlantic62,63.

The above results suggest that the SST response to the Saharan dust layer is a potentially important factor in the development of AZM, consistent with known interaction mechanisms linking AMM and AZM8,9,11,25. Specifically, the dust-induced meridional SSTA gradient intensifies the cooling of the surface water along the equator due to the increase of south-easterly cross-equatorial winds (Fig. 2a, b). The resultant pattern resembles a negative AZM phase during boreal spring (MAM; Figs. 2b and 3c). During the following summer, the cold anomalies subside, starting from the eastern margin of the equatorial Atlantic in MJJ, and extending westward from JAS to NDJ (Figs. 2c–f and 3c), similar to a positive AZM phase.

This reversal in the zonal SST gradient is a typical response to the arrival of a downwelling Kelvin wave (dKW), leading to positive heat content anomalies in the east which dissipates the cold anomalies associated with the negative AZM phase7,8,9,20. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 6, the regression analysis between the DAOD index and SSHA indicates wave activity during boreal spring and summer. A downwelling equatorial Rossby wave (dRW) is excited around 20∘W–3∘N to 6∘N (Fig. 6a) by Ekman convergence driven by negative wind curl anomaly in February and March around 20∘W –4∘N (contours in Figs. 6a and 4f). The dRW propagates westward from March to July and then reflects into a dKW on the coast of South America in July (Fig. 6b). The dKW propagates eastward along the equatorial Atlantic reaching the African coast in August–September. Its arrival causes the termination of the equatorial cooling and sets up favorable conditions for the development of the winter AZM (Figs. 6b and 2e, f). Subsequently, positive SSHAs from October to December, related to positive SSTAs, develop in the eastern basin, exhibiting a late-onset configuration of warm AZM in NDJ47 (Figs. 6b and 2f).

Lagged regression analysis of sea surface height anomalies (SSHAs; shaded colors) and wind-curl anomalies (contour lines) onto the January–March (JFM) Dust Aerosol Optical Depth index (DAOD anomalies averaged over the defined TNA region [45∘W–18∘W and 0–20∘N] for the period 1994 to 2022). a Wind curl and SSHA averaged within the 3∘N–6∘N band in the tropical Atlantic, indicating westward equatorial Rossby wave propagation. The longitude axis has been reversed to show reflection at the western boundary. b Same as (a), but averaged within the equatorial band 3∘S–3∘N, indicating an eastward propagating equatorial Kelvin wave. Significant values at 90% of confidence level based on a two-tailed Student t-test are stippled.

We thus find that the southern route of Saharan dust induces an SSTA gradient between TNA and the equatorial band, which is similar to the AMM, but with important distinctions. First, the warm SSTA is located along the Senegal coast (resembling the Dakar Niño64), while the typical AMM exhibits much more extended warming that covers the entire TNA65. Second, the AMM peaks during boreal spring, whereas the southern route of Saharan dust is most frequently observed during boreal winter27,43,65. Nevertheless, the common feature is that the interhemispheric SSTA gradient is associated with cross-equatorial winds that generate an anomalous wind curl north of the equator. This has been noted as a precursor for the reflected RW mechanism that contributes to the development and decay of the AZM8,9,20. Remarkably, during the study period, positive DAOD events affect the interannual equatorial SST variability both during the boreal spring cooling (MAM) and the subsequent warming in the next winter (Figs. 1c, 2 and 3c). Meanwhile, the AMM exhibits a noteworthy but only immediate impact on the AZM around JFM (blue line in Supplementary Fig. S4). This implies that Saharan dust acts as a distinctive driver for both spring and winter AZM (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Relation to climatic modes outside the tropical Atlantic

While equatorial Atlantic variability is known to affect the development of El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO)4, a statistically significant relationship between the El Niño3 index preceding dust events and vice versa is not evident (orange line in Supplementary Fig. S4 and Fig. S6). However, a negative correlation between the Niño3 index and the DAOD anomalies in JFM is seen about a year before, likely indicative of the manner in which ENSO events alter the wind regime of the tropics 66,67, which then affects dust production and transport over the Sahara33,68. Similarly, atmospheric patterns in the North Atlantic, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), can influence dust transport across the tropical Atlantic 69,70,71,72. In this context, regression maps of sea level pressure anomalies (SLPA) reveal an anomalous high-pressure system centered over the Iberian Peninsula and extending over the African continent during NDJ. This high-pressure system drives anomalous easterly winds, which likely facilitate the transport of dust over the TNA in winter (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Discussion

Saharan dust anomalies over the tropical North Atlantic (TNA) during winter are found to be an important source of equatorial Atlantic variability. As initially suggested by the lead-lag correlation analysis shown in Fig. 1c, Saharan dust induces equatorial cooling and a northward shift of the Atlantic Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) during boreal spring. About 6 months after the initial anomalies, the equatorial trend of anomalous sea surface temperature (SSTA) starts to reverse, showing a warming that lasts until the following winter, eventually leading to the dissipation of the initial cooling after about a year. This non-monotonic response to Saharan dust anomalies results from a sequence of thermodynamic and dynamic processes, triggered by dust-induced warming of air masses in the lower troposphere, commonly referred to as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL).

The sequence of processes is schematized in Fig. 7, separated into three phases. First, the radiatively-warmed SAL establishes a meridional air temperature gradient in the eastern TNA during JFM, driving northward wind anomalies that are deflected eastward along the western African coast due to the Coriolis effect. Similarly, the northward surface wind anomalies induce downwelling near the coast, which plays a dominant role in increasing heat content within the ocean’s mixed layer53,57. This warming is further enhanced by decreased evaporation through a wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback and reduced vertical mixing due to the increased stability of the warmed lower troposphere. In the second phase, surface warming spreads westward as a warm front in MAM, which drives cross-equatorial winds and subsequent northward migration of the ITCZ, as well as equatorial cooling. In the third phase, anomalous wind curl north of the equator excites a downwelling Rossby wave (dRW) that propagates westward and is boundary-reflected into a downward equatorial Kelvin wave (dKW). The eastward displacement of the dKW leads to a deepening of the thermocline and the activation of vertical diffusion, warming the equatorial band in NDJ8,9,20. This explains the delayed positive correlation between dust anomalies and equatorial SSTAs in the ATL3 region in the following winter (Figs. 1c, 2f, and S5).

Schematic summary of the impact of winter Saharan dust on equatorial Atlantic variability in three phases. Blue and red shades indicate cold and warm sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs), respectively. Curly orange arrows indicate latent heat flux; green arrows indicate anomalous negative wind curl and black arrows the wind anomalies. The first phase represents the strong warming in the eastern TNA induced by dust anomalies (brown, dotted wind symbol). The second phase depicts the westward expansion of a warm front and the resultant cross-equatorial winds, a northward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, and equatorial cooling. The third phase depicts a downwelling Rossby-Kelvin (dRW and dKW, respectively) reflection wave mechanism, induced by the cross-equatorial winds, which ultimately leads to warming in the eastern equatorial Atlantic, about a year after the initial dust anomaly.

The distinctive SST response linked to Saharan dust depicted in the first phase and shown in Fig. 2a is contingent upon the vertical distribution of dust aerosols in the lower troposphere, which is bottom heavy during winter43,46, as well as the prevailing shallow mixed layer depth (MLD) as shown in Fig. S2. The local warming response in the eastern TNA stands in contrast to the anticipated net cooling due to shortwave radiation blocking12,13,28. However, these results are consistent with model studies that reveal how changes in the atmospheric column due to the presence of dust can alter wind-stress curl, potentially leading to an increase in upper-ocean heat content and thereby counteracting the shortwave blocking effect41,42,73.

Phases two and three in Fig. 7 share similarities with the interaction between the Atlantic meridional and zonal modes (AMM and AZM, respectively) described in previous studies8,20,25. The response to Saharan dust anomalies during winter, nevertheless, has several important distinctions, such as a narrower warm front closer to the equator than typical AMM anomalies and a more abrupt forcing signal (Fig. 1c and blue line and red line in Supplementary Fig. S4). The response of the AZM to the dust anomalies of the southern route is also consistent with the tendency of the AZM to be dominated by the AMM during boreal winter25. However, the statistical relation of the delayed warm anomalies to the DAOD anomalies is stronger than seen with AMM (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating the important role of Saharan dust as a driver of the Rossby-Kelvin wave reflection mechanism.

In conclusion, the winter Saharan dust route is revealed as an important source of regional variability in the tropical Atlantic, shaping the intricate dynamics of the equatorial Atlantic. Moreover, given the statistical independence of dust anomalies from both the AMM and El Niño and the Southern Oscillation in the study period (Supplementary Fig. S4), winter Saharan dust anomalies may serve as a predictor of interannual variations in the equatorial Atlantic and its associated teleconnections. This underscores the necessity to improve the currently lacking representation of Saharan dust in global circulation models74,75,76,77.

Methods

Observational and reanalysis data

The main analyses are performed using a combination of observational atmospheric and ocean data. Monthly dust Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD) at 550 nm, sea surface temperature (SST), winds, total precipitation, and surface heat fluxes are obtained from assimilated diagnostics in the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications version 2 (MERRA2)78 at a horizontal resolution of 0.5∘ longitude by 0.625∘ latitude. Monthly mixed layer depth (MLD), defined as the depth where average seawater density exceeds near-surface density by 0.03 kg m−3, is derived from the ensemble mean of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Ocean Reanalysis System 5 (ORAS5)79 with a horizontal resolution of 0.25∘. Sea surface height anomaly (SSHA) is acquired from daily sea-level data by SSALTO/Data Unification and Altimeter Combination System (DUACS, horizontal resolution of 0.25∘), distributed by AVISO+ through the Copernicus Marine and Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00148).

To avoid influences by the Chicon (1983) and Pinatubo (1992) volcanic eruptions on DAOD80,81, all the analyses are performed over the period 1994 to 2022 (Supplementary Fig. S8). Monthly anomalies are accordingly computed for all variables by subtracting the climatological annual cycle derived from that period. To focus on interannual variability, monthly anomalies are also detrended by removing the low-frequency signal (which includes the global warming trend), achieved by applying a Butterworth filter with a 7-year cut-off frequency.

Climatic indices

The observational climate indices used in this study are: (i) the Sahara dust index (DAOD index), calculated as a three-month running mean of monthly DAOD anomalies over a defined region in the tropical North Atlantic ([TNA; 0∘–20∘N, 45∘W–18∘W], black box in Fig. 1a); (ii) The ATL3 index, also referred to as the Atlantic Zonal Mode (AZM) or the Atlantic Niño index, based on the three-month running mean of monthly sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTA) averaged over the ATL3 region [3∘S–3∘N, 20∘W–0∘], commonly used when considering interannual variability in the equatorial Atlantic4,7,18,82; (iii) the meridional position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) over the tropical Atlantic [20∘S–20∘N, 50∘W–20∘W], defined as the latitude of maximal tropical precipitation48; (iv) the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM; three-month running mean SSTA averaged [5∘N–28∘N, 20∘W–60∘W] minus [20∘S–5∘N, 30∘W–10∘E]8); and (v) the Niño-3 index (three-month running mean of SSTA averaged over the eastern equatorial pacific [5∘S–5∘N, 150∘W–90∘W]).

Regression analysis

The anomalies of ocean and atmospheric variables are regressed onto the DAOD index averaged in January–March (JFM) derived from MERRA2. The regressed fields shown in Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5a–c and 6 are based on a change of one standard deviation of the DAOD index (i.e., the regression coefficient multiplied by one standard deviation). The statistical significance levels are determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test, with 90% confidence interval bounds. The regression analysis is repeated, showing similar results, with monthly SST, surface winds, total precipitation from the ECMWF reanalysis version 5 (ERA5, regular horizontal resolution of 0.25∘; Supplementary Fig. S9)83. The DAOD taken from MERRA2 was validated with observational DAOD data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS; Supplementary Fig. S8)84. A sensitivity test for the correlations between DAOD and main variables (SSTA, QLH, QLH and Qekx) in the eastern TNA region is conducted using the bootstrap method with 10,000 iterations. In each bootstrap iteration, samples are drawn with replacement, and linear regression is applied to compute slopes, intercepts, and correlation coefficients. The resulting distributions of these metrics are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10 and further correlation coefficients with other variables are shown in correlation matrix of Supplementary Fig. S11.

Composite analysis

Positive and negative years are defined as those where the mean of the DAOD index is equal to or higher than one standard deviation (for positive years) or equal to or lower than minus one standard deviation (for negative years) in the defined TNA region [0∘–20∘N, 45∘W–18∘W] during winter (JFM). Based on these criteria, a total of seven positive years (1997, 2000, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2012, 2016) and seven negative years (1996, 1999, 2005, 2006, 2009, 2011, and 2013) are selected for the composite analysis. Statistical significance is assessed using a Monte Carlo approach, which involves generating 10,000 random composites with the same number of positive and negative events from the entire time series. This large number of iterations enables the implementation of a 95% confidence level based on a two-tailed t-test. Refer to Fig. 3c for the negative and positive composite years of the DAOD index, SSTA in the eastern TNA, and the ATL3 index.

Mixed layer heat balance equation

We assume that the mixed layer temperature tendency \(\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}\), in the eastern TNA is primarly driven by net surface heat flux Q0 and Ekman heat flux Qek. Here we calculate it using monthly values following the Equation (1),

where ρ and C denote the density (ρ = 1025 kg m−1) and heat capacity of ocean water (C = 3850 J kg−1 C−1), respectively, h is the depth of the climatological mixed layer (Fig. S2), and ϵ denotes residuals which includes vertical mixing and entrainment. The net heat flux into the mixed layer, as shown in Equation (2), is composed of the sensible heat flux QSH, latent heat flux QLH, longwave radiative flux QLW, and net shortwave radiative flux QSW, minus the penetrative shortwave radiative component Qp

where Qp is calculated as a 25 m e-folding decay of shortwave radiation, given by the equation Qp = 0.45 QSWe−γh, with γ a decay rate constant equal to 0.04 m−132.

The Ekman heat flux Qek is given by the Equation (3),

where τy and τx are the meridional and zonal components of the surface wind stress, respectively, and f is the Coriolis parameter.

MERRA2 and associated uncertainties

Since the mid-1990s, there has been a substantial increase in the volume and quality of assimilated observations in the MERRA2 reanalysis78. This improvement is largely due to the proliferation of satellite data and the expansion of land-based monitoring stations. As a result, data biases have significantly diminished from this period onwards, which aligns with the timeframe of our analysis.

For comprehensive details on the MERRA2 reanalysis product, including its description and evaluation, readers are encouraged to refer to the extensive documentation available in a special collection of articles published in the Journal of Climate (https://journals.ametsoc.org/collection/MERRA2). However, we will briefly discuss the reliability of the data used in our study and highlight potential sources of uncertainty.

Dust aerosol optical depth (DAOD)

The inclusion of DAOD data incorporates ground-based observations from the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) and satellite reflectances from the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) and MODIS. MERRA2 is one of the few reanalyses where aerosol fields are radiatively coupled to the atmosphere at hourly resolution over multidecadal timescales, providing unique insights into climate variability associated with aerosol radiative effects78.

The dust transport over the tropical Atlantic Ocean has been evaluated through comparisons with individual AERONET stations located in Dakar, Cape Verde, and Barbados85,86 and the impact of data assimilation was assessed using a control simulation86. The time series comparison of DAOD derived from MERRA2 with the Cape Verde station [16.73N, 22.94W] demonstrated a strong agreement, evidenced by a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.92 (see Fig. 8 in ref. 85). Similarly, comparisons of hourly data for an individual dust event in April 2010 showed very high Pearson correlation coefficients (≥0.95) for both Dakar [14.39N, 16.96W] and Barbados [13.16N, 59.43W]. In contrast, the non-assimilation version displayed lower correlations of 0.86 and 0.69, respectively86. While some caution must be applied considering the challenges of independent validation of DAOD (i.e., differences in data coverage), overall, MERRA2 effectively reproduces realistic variability in the TNA, making it well-suited for investigating aerosol-climate interactions at interannual timescales, as presented in this study.

SST and wind

The boundary conditions for SST in MERRA2 are based on a combination of observational products of varying resolutions to cover the entire analysis period (see Table 3 in ref. 78). This combination of datasets can potentially lead to inconsistencies during the processing into a unified gridded set for boundary conditions. Despite careful processing, MERRA2 SST data show systematic differences compared to other reanalysis products, with a global mean SST that is slightly cooler by less than 0.5 K (see Fig. 5 in ref. 78). Given these differences, we independently validated MERRA2 SST against Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST)87 by mapping the error-to-variability ratio across the tropical Atlantic and examining the linear relationship (Supplementary Fig. S12). The resulting low error-to-variability ratio (<1) suggests that MERRA2 SST errors are minimal compared to the natural variability of the data within our study domain, while a high regression coefficient of 0.92 indicates a strong alignment between the datasets. Winds, which are assimilated from QuickSCAT scatterometer and multiplatform observations show values within the same range as other reanalysis datasets88. The results shown from regression analysis using SST and wind field derived from the ERA5 reanalysis (Supplementary Fig. S9) are consistent with the results derived from MERRA2.

Radiative fluxes and precipitation

Radiative transfer calculations in MERRA2 are based on multiple satellite radiances (see Table 2 in ref. 78) and utilize the Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM)89. The accuracy of surface radiative heat fluxes is significantly influenced by cloud parameterizations within the radiative models. In MERRA2, clouds are overrepresented in tropical regions, leading to systematic biases compared to observations90. However, this overrepresentation is particularly pronounced in the warm-pool region on the western side of the TNA and over land areas, though it is less significant in the eastern TNA. Regarding the precipitation data in MERRA2, which includes both model-generated and observation-corrected values, are similarly affected by model physics and parameterizations, such as those for convection. The model-generated precipitation maintains global mass conservation, balancing precipitation and evaporation88. For consistency, our study uses model-generated precipitation, treating it as a response rather than a driving mechanism. Discrepancies between model-generated precipitation and observations are most pronounced over land areas with considerable topography88, likely due to the model’s limitations in resolving small-scale convective dynamics where precipitation variability is high. Compared to Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) data91, MERRA2 shows excessive precipitation along the Gulf of Guinea coast, while differences in the central and eastern TNA are less pronounced88. Thus, careful interpretation is required for precipitation data over land and coastal regions.

Data availability

Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications version 2 (MERRA2) data were downloaded from MDISC, managed by the NASA Goddard Earth Sciences (GES) Data and Information Services Center (DISC) at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets?project=MERRA-2. AVISO daily global Sea Surface Height (SSH) was downloaded from The Copernicus Marine and Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) at https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_CLIMATE_L4_MY_008_057/description. MODIS monthly L3 Dust Aerosol Optical Depth (DAOD) provided by The Level-1 and Atmosphere Archive and Distribution System Distributed Active Archive Center (LAADS DAAC) was downloaded at https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/missions-and-measurements/products/MYD08_M3. European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis version 5 (ERA5) and Ocean Reanalysis System 5 (ORAS5) monthly data were downloaded from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/.

Code availability

All analyses and statistical evaluation were performed using the Python packages xarray92, which is available at https://docs.xarray.dev/en/stable/, xarrayutils93 available at https://xarrayutils.readthedocs.io/en/latest/, scikit-learn94 available at https://scikit-learn.org/stable/and SciPy95 available at https://scipy.org/. The Python codes used to perform the analyses and figures can be accessed upon request to I.V.C.

References

Nobre, P. & Shukla, J. Variations of sea surface temperature, wind stress, and rainfall over the tropical Atlantic and South America. J. Clim. 9, 2464–2479 (1996).

Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. et al. Interannual and decadal SST-forced responses of the West African monsoon. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 12, 67–74 (2011).

Kim, D. et al. Increase in Cape Verde hurricanes during Atlantic Niño. Nat. Commun. 14, 3704 (2023).

Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. et al. Are Atlantic Niños enhancing Pacific ENSO events in recent decades? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L207205 (2009).

García-Serrano, J., Losada, T. & Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. Extratropical atmospheric response to the Atlantic Niño decaying phase. J. Clim. 24, 1613–1625 (2011).

Yadav, R. K., Srinivas, G. & Chowdary, J. S. Atlantic Niño modulation of the Indian summer monsoon through Asian jet. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 23 (2018).

Lübbecke, J. F. et al. Equatorial Atlantic variability—Modes, mechanisms, and global teleconnections. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 9, e527 (2018).

Foltz, G. R. & McPhaden, M. J. Interaction between the Atlantic meridional and Niño modes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L18604 (2010).

Martín-Rey, M. & Lazar, A. Is the boreal spring tropical Atlantic variability a precursor of the Equatorial Mode? Clim. Dyn. 53, 2339–2353 (2019).

Richter, I., Tokinaga, H. & Okumura, Y. M. The extraordinary equatorial Atlantic warming in late 2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL095918 (2022).

Martín-Rey, M., Vallès-Casanova, I. & Pelegrí, J. L. Upper-Ocean Circulation and Tropical Atlantic Interannual Modes. J. Clim. 36, 2625–2643 (2023).

Foltz, G. R. & McPhaden, M. J. Impact of Saharan dust on tropical North Atlantic SST. J. Clim. 21, 5048–5060 (2008).

Evan, A. T., Foltz, G. R., Zhang, D. & Vimont, D. J. Influence of African dust on ocean–atmosphere variability in the tropical Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 4, 762–765 (2011).

Luo, B., Minnett, P. J., Zuidema, P., Nalli, N. R. & Akella, S. Saharan dust effects on North Atlantic sea-surface skin temperatures. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 126, e2021JC017282 (2021).

Song, Z., Lee, S.-K., Wang, C., Kirtman, B. P. & Qiao, F. Contributions of the atmosphere–land and ocean–sea ice model components to the tropical Atlantic SST bias in CESM1. Ocean Model 96, 280–290 (2015).

Richter, I. & Tokinaga, H. An overview of the performance of CMIP6 models in the tropical Atlantic: mean state, variability, and remote impacts. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2579–2601 (2020).

Chang, P., Saravanan, R., Ji, L. & Hegerl, G. C. The effect of local sea surface temperatures on atmospheric circulation over the tropical Atlantic sector. J. Clim. 13, 2195–2216 (2000).

Keenlyside, N. S. & Latif, M. Understanding equatorial Atlantic interannual variability. J. Clim. 20, 131–142 (2007).

Richter, I. et al. Multiple causes of interannual sea surface temperature variability in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean. Nat. Geosci. 6, 43–47 (2013).

Martín-Rey, M., Polo, I., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B., Lazar, A. & Losada, T. Ocean dynamics shapes the structure and timing of Atlantic equatorial modes. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 124, 7529–7544 (2019).

Giannini, A., Saravanan, R. & Chang, P. Oceanic forcing of Sahel rainfall on interannual to interdecadal time scales. Science 302, 1027–1030 (2003).

Polo, I., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B., Losada, T. & García-Serrano, J. Tropical Atlantic variability modes (1979–2002). Part I: Time-evolving SST modes related to West African rainfall. J. Clim. 21, 6457–6475 (2008).

Losada, T. et al. A multi-model approach to the Atlantic Equatorial mode: impact on the West African monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 35, 29–43 (2010).

Nicholson, S. E., Fink, A. H., Funk, C., Klotter, D. A. & Satheesh, A. R. Meteorological causes of the catastrophic rains of October/November 2019 in equatorial Africa. Glob. Planet. Change 208, 103687 (2022).

Servain, J., Wainer, I., McCreary, J. P. Jr & Dessier, A. Relationship between the equatorial and meridional modes of climatic variability in the tropical Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 485–488 (1999).

Zhu, J., Huang, B. & Wu, Z. The role of ocean dynamics in the interaction between the Atlantic meridional and equatorial modes. J. Clim. 25, 3583–3598 (2012).

Ben-Ami, Y., Koren, I., Altaratz, O., Kostinski, A. & Lehahn, Y. Discernible rhythm in the spatio/temporal distributions of transatlantic dust. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 2253–2262 (2012).

Evan, A. T., Vimont, D. J., Heidinger, A. K., Kossin, J. P. & Bennartz, R. The role of aerosols in the evolution of tropical North Atlantic ocean temperature anomalies. Science 324, 778–781 (2009).

Xian, P. et al. Revisiting the relationship between Atlantic dust and tropical cyclone activity using aerosol optical depth reanalyses: 2003–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 15357–15378 (2020).

Li, F., Vogelmann, A. & Ramanathan, V. Saharan dust aerosol radiative forcing measured from space. J. Clim. 17, 2558–2571 (2004).

Parajuli, S. P., Jin, Q. & Francis, D. Atmospheric dust: How it affects climate, environment and life on Earth? Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1058052 (2022).

Wang, W. & McPhaden, M. J. The surface-layer heat balance in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Part I: Mean seasonal cycle. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 29, 1812–1831 (1999).

Prospero, J. M. & Lamb, P. J. African droughts and dust transport to the Caribbean: Climate change implications. Science 302, 1024–1027 (2003).

Kaufman, Y. J., Koren, I., Remer, L. A., Rosenfeld, D. & Rudich, Y. The effect of smoke, dust, and pollution aerosol on shallow cloud development over the Atlantic Ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 11207–11212 (2005).

Prenni, A. J. et al. Relative roles of biogenic emissions and Saharan dust as ice nuclei in the Amazon basin. Nat. Geosci. 2, 402–405 (2009).

Rosenfeld, D. et al. Global observations of aerosol-cloud-precipitation-climate interactions. Rev. Geophys. 52, 750–808 (2014).

Francis, D. et al. Summertime dust storms over the Arabian Peninsula and impacts on radiation, circulation, cloud development, and rain. Atmos. Res. 250, 105364 (2021).

Dunion, J. P. & Velden, C. S. The impact of the Saharan Air Layer on Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 85, 353–366 (2004).

Huang, J. et al. Satellite-based assessment of possible dust aerosols semi-direct effect on cloud water path over East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L19802 (2006).

Francis, D. et al. The dust load and radiative impact associated with the June 2020 historical Saharan dust storm. Atmos. Environ. 268, 118808 (2022).

Strong, J. D., Vecchi, G. A. & Ginoux, P. The response of the tropical Atlantic and West African climate to Saharan dust in a fully coupled GCM. J. Clim. 28, 7071–7092 (2015).

Chen, S.-H. et al. Impacts of Saharan mineral dust on air-sea interaction over North Atlantic Ocean using a fully coupled regional model. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 126, e2020JD033586 (2021).

Barreto, A. et al. Long-term characterisation of the vertical structure of the Saharan Air Layer over the Canary Islands using lidar and radiosonde profiles: implications for radiative and cloud processes over the subtropical Atlantic Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 739–763 (2022).

Formenti, P. et al. Regional variability of the composition of mineral dust from western Africa: Results from the AMMA SOP0/DABEX and DODO field campaigns. J. Geophys. Res. : Atm. 113, D00C13 (2008).

Johnson, B. et al. Vertical distribution and radiative effects of mineral dust and biomass burning aerosol over West Africa during DABEX. J.Geophys. Res.: Atm. 113, D00C12 (2008).

Tsamalis, C., Chédin, A., Pelon, J. & Capelle, V. The seasonal vertical distribution of the Saharan Air Layer and its modulation by the wind. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 11235–11257 (2013).

Vallès-Casanova, I., Lee, S.-K., Foltz, G. R. & Pelegrí, J. L. On the spatiotemporal diversity of Atlantic Niño and associated rainfall variability over West Africa and South America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087108 (2020).

Adam, O., Bischoff, T. & Schneider, T. Seasonal and interannual variations of the energy flux equator and ITCZ. Part I: Zonally averaged ITCZ position. J. Clim. 29, 3219–3230 (2016).

Wilcox, E. M., Lau, K. & Kim, K.-M. A northward shift of the North Atlantic Ocean Intertropical Convergence Zone in response to summertime Saharan dust outbreaks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L04804 (2010).

Okumura, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Some overlooked features of tropical Atlantic climate leading to a new Niño-like phenomenon. J. Clim. 19, 5859–5874 (2006).

Foltz, G. R., Schmid, C. & Lumpkin, R. Seasonal cycle of the mixed layer heat budget in the northeastern tropical Atlantic Ocean. J. Clim. 26, 8169–8188 (2013).

Chen, W. A decadal weakening in the connection between ENSO and the following spring SST over the northeast tropical Atlantic after the mid-1980s. J. Clim. 35, 2867–2881 (2022).

Wade, M. et al. Interdecadal changes in SST variability drivers in the Senegalese-upwelling: the impact of ENSO. Clim. Dyn. 60, 667–685 (2023).

Thiam, M. et al. Impact of the sea surface temperature in the north-eastern tropical Atlantic on precipitation over Senegal. J. Geophys. Res.: Atm. 129, e2023JD040513 (2024).

Carlson, T. N. & Prospero, J. M. The large-scale movement of Saharan air outbreaks over the northern equatorial Atlantic. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 11, 283–297 (1972).

Wong, S., Dessler, A. E., Mahowald, N. M., Yang, P. & Feng, Q. Maintenance of lower tropospheric temperature inversion in the Saharan Air Layer by dust and dry anomaly. J. Clim. 22, 5149–5162 (2009).

Faye, S., Lazar, A., Sow, B. A. & Gaye, A. T. A model study of the seasonality of sea surface temperature and circulation in the Atlantic North-eastern Tropical Upwelling System. Front. Phys. 3, 76 (2015).

Karnauskas, K. B. A simple coupled model of the wind–evaporation–SST feedback with a role for stability. J. Clim. 35, 2149–2160 (2022).

Chang, P., Fang, Y., Saravanan, R., Ji, L. & Seidel, H. The cause of the fragile relationship between the Pacific el Niño and the Atlantic Niño. Nature 443, 324–328 (2006).

Mittelstaedt, E. The upwelling area off Northwest Africa—a description of phenomena related to coastal upwelling. Prog. Oceanogr. 12, 307–331 (1983).

Doi, T., Tozuka, T. & Yamagata, T. Interannual variability of the Guinea Dome and its possible link with the Atlantic Meridional Mode. Clim. Dyn. 33, 985–998 (2009).

Zebiak, S. E. Air–sea interaction in the equatorial Atlantic region. J. Clim. 6, 1567–1586 (1993).

Carton, J. A. & Huang, B. Warm events in the tropical Atlantic. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 24, 888–903 (1994).

Oettli, P., Morioka, Y. & Yamagata, T. A regional climate mode discovered in the North Atlantic: Dakar Niño/Niña. Sci. Rep. 6, 18782 (2016).

Amaya, D. J., DeFlorio, M. J., Miller, A. J. & Xie, S.-P. Wes feedback and the Atlantic meridional mode: Observations and CMIP5 comparisons. Clim. Dyn. 49, 1665–1679 (2017).

Roy, C. & Reason, C. ENSO related modulation of coastal upwelling in the eastern Atlantic. Prog. Oceanogr. 49, 245–255 (2001).

García-Serrano, J., Cassou, C., Douville, H., Giannini, A. & Doblas-Reyes, F. J. Revisiting the ENSO teleconnection to the tropical North Atlantic. J. Clim. 30, 6945–6957 (2017).

DeFlorio, M. J. et al. Interannual modulation of subtropical Atlantic boreal summer dust variability by ENSO. Clim. Dyn. 46, 585–599 (2016).

Prospero, J. Saharan dust transport over the North Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean: An overview. In The impact of desert dust across the Mediterranean (eds Guerzoni, S. & Chester, R.), Vol 11, 133–151. (Dordrecht: Springer, 1996).

Evan, A. T., Heidinger, A. K. & Knippertz, P. Analysis of winter dust activity off the coast of West Africa using a new 24-year over-water advanced very high resolution radiometer satellite dust climatology. J. Geophys. Res. Atm. 111, D12210 (2006).

Riemer, N., Doherty, O. & Hameed, S. On the variability of African dust transport across the Atlantic. Geophysical Res. Lett. 33 (2006).

Nakamae, K. & Shiotani, M. Interannual variability in Saharan dust over the North Atlantic Ocean and its relation to meteorological fields during northern winter. Atmos. Res. 122, 336–346 (2013).

Martinez Avellaneda, N.The impact of Saharan dust on the North Atlantic circulation. Ph.D. thesis, Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky (2010).

Evan, A. T., Flamant, C., Gaetani, M. & Guichard, F. The past, present and future of African dust. Nature 531, 493–495 (2016).

Adebiyi, A. A. & Kok, J. F. Climate models miss most of the coarse dust in the atmosphere. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9507 (2020).

O’Sullivan, D. et al. Models transport Saharan dust too low in the atmosphere: a comparison of the MetUM and CAMS forecasts with observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 12955–12982 (2020).

Zhao, A., Ryder, C. L. & Wilcox, L. J. How well do the CMIP6 models simulate dust aerosols? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 2095–2119 (2022).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Zuo, H., Balmaseda, M. A., Tietsche, S., Mogensen, K. & Mayer, M. The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: a description of the system and assessment. Ocean Sci 15, 779–808 (2019).

Rampino, M. R. & Self, S. The atmospheric effects of el Chichon. Sci. Am. 250, 48–57 (1984).

McCormick, M. P., Thomason, L. W. & Trepte, C. R. Atmospheric effects of the Mt Pinatubo eruption. Nature 373, 399–404 (1995).

Losada, T., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. & Kucharski, F. Tropical influence on the summer Mediterranean climate. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 13, 36–42 (2012).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Remer, L. A., Tanré, D., Kaufman, Y. J., Levy, R. & Mattoo, S. Algorithm for remote sensing of tropospheric aerosol from MODIS: Collection 005. NASA, 87pp. (2006).

Randles, C. et al. The MERRA-2 aerosol reanalysis, 1980 onward. Part I: System description and data assimilation evaluation. J. Clim. 30, 6823–6850 (2017).

Buchard, V. et al. The MERRA-2 aerosol reanalysis, 1980 onward. Part II: Evaluation and case studies. J. Clim. 30, 6851–6872 (2017).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the daily optimum interpolation sea surface temperature (DOISST) version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Bosilovich, M. G., Lucchesi, R. & Suarez, M. MERRA-2: File specification. NASA GMAO Office Note 9, 75pp. (2015).

Han, Y. JCSDA community radiative transfer model (CRTM): Version 1 (2006).

Hinkelman, L. M. The global radiative energy budget in MERRA and MERRA-2: Evaluation with respect to CERES EBAF data. J. Clim. 32, 1973–1994 (2019).

Adler, R. F. et al. The version-2 global precipitation climatology project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979-present). J. Hydrometeorol. 18, 1147–+ (2017).

Hoyer, S. & Hamman, J. xarray: N-D labeled arrays and datasets in Python. J. Open Res. Softw. 5, 10–10 (2017).

Busecke, J. & Hogikyan, A. xarrayutils (2023).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by ISF grant 1022/21. M.M.R. has been supported by Ramón y Cajal (RYC2022-038454-I, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and co-funded by the FSE+,European Union) and the Spanish project DISTROPIA (PID2021-125806NB-I00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.V.C. designed and performed the analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. O.A. supervised the work, interpreted the results, and contributed to the writing. M.M.R. contributed to the interpretation of the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Diana Francis and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kerstin Schepanski, Heike Langenberg, Alienor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vallès-Casanova, I., Adam, O. & Martín Rey, M. Influence of winter Saharan dust on equatorial Atlantic variability. Commun Earth Environ 6, 31 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01926-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01926-2