Abstract

Arctic sea-ice extent has reduced by over 40% during late summer since 1979, and the day-to-day changes in sea ice extent have shifted to more negative values. Drivers of Arctic weather that cause large short-term changes are rarely predicted more than a week in advance. Here we investigate variability in changes in sea ice extent for periods of less than 18 days and their association to Arctic cyclones and tropopause polar vortices. We find that these very rapid sea ice loss events are substantial year-round and have increased over the last 30 years in June-August due to thinning sea ice that is more susceptible to forcings from ocean waves and low-level atmospheric wind. These events occur in regions of enhanced near-surface level pressure gradients between synoptic-scale high and low pressure systems over regions of relatively thin sea ice, and are preceded by tropopause polar vortices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arctic has undergone dramatic changes in temperature and in sea ice extent since routine measurements have begun, with temperatures warming at more than double the rate of the global average1,2,3,4 and September sea ice extent (SIE) declining by over 40%5. Greater warming in the Arctic than surrounding lower latitudes, referred to as Arctic amplification, can largely be explained by the influence of declining sea ice on atmospheric radiative feedbacks. The presence of sea ice elevates atmospheric stability and inhibits the increase in longwave energy radiated back to space in response to surface warming compared to ice-free regions6. In addition, absorption of solar radiation at the surface increases when snow and ice retreat7,8,9,10,11,12. From October - January, when incoming solar radiation is largely absent, the increasing surface air temperature trends are largely associated with the increase in the downward longwave radiation13. However, even though global climate models incorporate such feedback processes, ensemble projections of sea ice decline tend to be quite conservative with respect to the observed trends14,15,16,17,18. Recently, evidence has been mounting on the impact that Arctic cyclones can have on sea ice at very short time scales19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. The present study will establish that Arctic cyclones associated with sea ice loss at short time scales occur in areas of relatively thin sea ice where there are enhanced pressure gradients. Though the exact mechanisms of how an Arctic cyclone can rapidly change sea ice are incompletely understood, some studies suggest that ocean waves induced by the wind of an Arctic cyclone on the surface can break up sea ice under certain conditions18,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Even when Arctic cyclones are well-represented in numerical models35,36,37, the sea ice dynamics surrounding upper-ocean mixing and the breakup due to waves is a missing process in most models, resulting in little skill in sea ice reductions due to Arctic cyclones18. Notwithstanding sea ice reductions alone, there is growing evidence that a warming Arctic can impact large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns throughout the Northern Hemisphere38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, thus gaining knowledge of the variability in sea ice due to short time-scale features such as Arctic cyclones is important in order to assess the global risks of climate change. This study investigates the relatively short, synoptic-timescale reductions in sea ice, which we call very rapid sea ice loss events (VRILEs), and whether there are common atmospheric features associated with VRILEs such as Arctic cyclones.

The term RILE49, for rapid ice loss event, describes the very large, intermittent trends of about 5-yr duration in September SIE, first discovered in global climate models50 and seen in the Arctic over 2007–2012. Back-to-back years with an enhanced frequency of VRILEs could lead to a RILE. A fundamental understanding of how Arctic cyclones could cause VRILEs is lacking and VRILEs have not been predicted more than a week or two in advance51,52. The timing of Arctic cyclones and the state of the underlying sea ice are important factors that influence the sea ice response27,53,54. When a surface cyclone develops early in summer, it may act to preserve sea ice by increasing cloud cover and decreasing the surface absorbed solar radiation25,55. In contrast, while most surface cyclones do not lead to ice loss25,26,56, it may be possible for a surface cyclone in late summer to enhance melt or inhibit growth by mixing up heat from the upper ocean’s near-surface temperature maximum that may otherwise be sequestered under a freshwater capping layer21,27. Cyclone-driven ocean surface waves can propagate further into thinner sea ice, accelerating sea ice floe breakup29,30,34,57,58. The region subject to wave propagation, known as the Marginal Ice Zone (MIZ), with lower sea ice concentration rimming the more concentrated pack ice, has widened in summer in recent decades59.

Results and discussion

Arctic cyclones

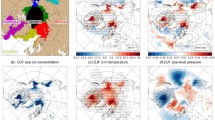

One source of short timescale variability in SIE are atmospheric forcings associated with synoptic-scale Arctic cyclones60. Arctic cyclones can have radii of up to ~2000 km61, lifetimes as long as several weeks23, are frequently located in the central Arctic Ocean during the summer62, and often form in association with tropopause polar vortices (TPVs)19,23,63,64,65,66,67,68,69, when an upper-level potential vorticity anomaly moves over a lower-level temperature gradient63,70. TPVs are generally sub-synoptic scale features on the tropopause that can be present days to months before an Arctic cyclone forms71 and thus could offer insight into the physical processes that are important for VRILEs. An example of an Arctic cyclone and TPV (8- and 85-day lifetimes, respectively) in August 2006 is shown in Fig. 1a, colocated in a region of reduced sea ice near the MIZ of the North Atlantic (Fig. 1b). This area of reduced sea ice was not present before the cyclone, suggesting the possibility that ocean waves and/or atmospheric wind from the cyclone may have played an important role in the rapid loss of sea ice. While this is just one example of an Arctic cyclone and TPV associated with an apparent VRILE, we will evaluate the significance, frequency, and characteristics of short timescale variability in Arctic SIE under the hypothesis that Arctic cyclones and TPVs are a common association to VRILEs.

a Potential temperature on the dynamic tropopause (colors; color interval 5 K) and sea level pressure (black contours; contour interval 4 hPa; only values at or below 1004 hPa are shown) at 00 UTC 21 August 2006 and b sea ice concentrations (colors) from passive microwave satellite radiometry composited over 21 August 2006. The red rectangle highlights a region of locally low sea ice concentration (b) under an observationally-based reanalysis of a TPV and Arctic cyclone (a). The dynamic tropopause is the 2 PVU surface, where 1 PVU = 106 K m2 kg−1 s−1. The sea ice concentration points near the pole (latitudes ≥ 87.5°N) are masked out.

Short timescale variability in Arctic sea ice

Observations indicate that variability in SIE (Fig. 2a) and in moving 3-day sums in daily changes in Arctic sea ice extent (ΔSIE) (Fig. 2b) is substantial not only for intraseasonal and seasonal timescales, but also for shorter timescales of about 18 days or less. Since changes in SIE can, to some extent, be persistent, we expect that ΔSIE is less susceptible to persistence and more to atmospheric forcing; hence, we subsequently choose to focus on ΔSIE for the remainder of this analysis. The observation shown here that ΔSIE variability is significant at timescales of 18 days or less motivates an analysis of ΔSIE that further isolates these shorter timescales as described below. While global climate model projections from the Community Earth System Model-Large Ensemble (CESM-LE)72 reproduce variability in ΔSIE quite well for periods of over 40 days, variability in ΔSIE is substantially lower than observations for shorter timescales18. This could mean VRILEs may not be a significant contribution to ΔSIE in CESM-LE and that the CESM-LE, and potentially other climate models, are not representing the physical processes that produce VRILEs. Furthermore, observed atmospheric variability from intraseasonal variations such as the Arctic Oscillation (AO) and North Atlantic Oscillation are significant at timescales of as short as 1 week (not shown), and since ΔSIE is in part associated with these patterns of atmospheric variability40,73,74,75, CESM-LE may also not be representing the full range of impacts from them.

a SIE and b ΔSIE power spectral density (PSD) for a random CESM-LE ensemble member projection of the near present day equivalent period (green) compared to observations from the NSIDC sea ice index (1989–2023; blue). The 95% confidence interval from the theoretical red noise spectrum (dashed red) is also shown, and thus PSD values above this dashed red line indicate statistically significant a SIE or b ΔSIE variability. The vertical dashed black line denotes the 18-day cutoff period used in the high bandpass filter to retain the weather timescales. Units of PSD here are (variance Hz−1).

VRILEs occur throughout the year, but have the largest sea ice reduction during the warm season of June, July, and August (JJA), when they also exhibit an increasing frequency in the most recent decade, and partially contribute to the increasing variability in September SIE (Fig. 3). The largest sea ice reductions occur in June and July, when each VRILE consists of around 0.3–0.7 × 106 km2 of SIE reduction (Fig. 3a). From September to February, when there is typically expansion in SIE due to freezing, VRILEs occur when there is simply less expansion in SIE rather than a reduction in SIE. In contrast, warm-season VRILEs can have a long-lasting impact on SIE since VRILEs are typically associated with 0.2–0.3 × 106 km2 more ice loss than the typical background SIE reduction. VRILE frequencies usually consist of a cold-season peak between October and February and a warm-season peak in July or August (Fig. 3b). As will be described in further detail in “Methods”, we separate VRILEs into two types based on the method used to calculate them. The first method (ΔSIEmean removed) are extreme ΔSIE events based on anomalies with respect to the climatological mean, while the second method (ΔSIEbwfilt) isolates the events associated with only the short timescales that have significant variability in observations. ΔSIEmean removed (containing daily values) exhibits a statistically significant positive trend over time during the summer (Table 1), with the largest increases in frequency during the summer of the most recent decade (Fig. 3c and Table 2). This trend in ΔSIEmean removed is not surprising, given the mean SIE of the most recent decade is much lower than previous decades76. Since ΔSIEbwfilt can be attributed to high-frequency variability, there are considerably fewer events than ΔSIEmean removed with no long-term trends since these longer-term variations have been removed by the Butterworth Filter. In 2012, six of the twelve summer (June-August) VRILEs occurred at the same time as the Great Arctic cyclone19, while there are six ΔSIEmean removed events in the “preconditioning” period in which a persistent anticyclone promoted warm temperatures and hence a prolonged period favoring ice melt in June53.

a The 30-yr climatological range of ΔSIE (gray) compared with the bottom 5th percentile mean-removed VRILEs (ΔSIEmean removed; red) and range of filtered VRILEs (ΔSIEbwfilt; blue). Distribution of the (b) number of VRILEs for decadal periods with 1991 through 2001 (black), 2002 through 2012 (blue), and 2013 through 2023 (red) by month and (c) total number of filtered VRILEs (blue) plus mean-removed VRILEs (red) in June-August (JJA) by year. d 1 September SIE (black) and 1 September SIE minus the accumulated sea ice reductions from ΔSIEtotal (gray). The fractional reduction in SIE from ΔSIEtotal (red) is shown for comparison using Equation (1) and expressed as a percentage. The number of VRILEs for decadal periods 1991 through 2001 (black), 2002 through 2012 (blue), and 2013 through 2023 (red) by ΔSIE for (e) JJA and (f) all months except JJA.

The accumulated reduction in warm season SIE from VRILEs contributes to as much as ~1 × 106 km2 of the seasonal loss and is significantly increasing in time at a rate of 3.1% per decade (p-value of 1.78 × 10−3), with over 20% of the total warm season reduction in SIE in 2012, 2018, and 2019 occurring from all ΔSIE events (Fig. 3d). The pattern of interannual variability in SIE does not change much in consideration of ΔSIE, implying that large year-to-year differences in SIE can not be attributed to VRILEs alone. The ΔSIE per VRILE is also increasing during the warm season, especially in the extreme loss categories of 0.5–0.6 × 106 km2 of sea ice loss per event (Fig. 3e), and is similar to those outside of the summer season (Fig. 3f).

Spatial characteristics of very rapid sea ice loss events

We next show there are common atmospheric patterns associated with VRILEs, hypothesizing that sufficiently thin sea ice in summer is systematically associated with strong atmospheric winds since winds can potentially promote accelerations in ice loss through processes such as breakup of ice from ocean waves or ocean upwelling. The 1st-year ice age extent contour is used as an approximate measure of the relatively thin vs. thick sea ice since sea ice that is less than 1 year old is at least thin enough to succumb to seasonal forcing.

On average, VRILEs occur in regions of relatively strong low-level atmospheric pressure gradients in combination with thinner, younger sea ice (Fig. 4). During the warm season, the combined low-level pressure gradient and thin sea ice occurs over a broad region of the Arctic Ocean centered over the northern Beaufort Sea between the Beaufort High Pressure and Arctic cyclones (Fig. 4a, c), while the rest of the year they are mostly in the 1st-year ice of the MIZs of the North Atlantic and North Pacific between the Beaufort High Pressure and cyclones in the midlatitude storm track (Fig. 4b, d). Note that Hudson Bay has been becoming increasingly more ice free during the warm season, leading to fewer VRILEs over time (compare Figs. 4a, c). Outside of the warm season, there are a high number of VRILEs in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea, also in locations where sea-level pressure gradients are enhanced between the synoptic-scale cyclones in the North Pacific storm track and the Beaufort High along the MIZ. Indeed, when averaged relative to the location of the VRILE, it is clearly evident that the VRILE location is centered in a region with an enhanced pressure gradient between a surface cyclone and anticyclone (Fig. 4e). On average, VRILEs are associated with a nearby surface cyclone and tropopause polar vortex (TPV) (Fig. 4f), and all surface cyclone cases are associated with an antecedent TPV (not shown). These results are consistent with a previous study, where it was found that nearly all very-intense cyclones were related to a TPV64. On average, the surface cyclone and TPV exhibit a tilt with height at the time of the VRILEs, which indicates the surface cyclones are generally strengthening at the time of the VRILE.

a–d Locations of filtered VRILEs, computed with (ΔSIEbwfilt), and e, f June-August 1989–2023 composite tropopause potential temperature (colors) and sea level pressure (contours) standardized anomalies. Filtered VRILE locations in a, c are for June–August while b, d are for non June–August months for the years a, b 1989–1998 and c, d 2014–2023. VRILE locations are determined by the number of sea ice concentration loss objects at any 0.5° grid point. In (a–d), mean sea level pressure is shown by gray contours with a 1 hPa interval and thick (thin) cyan contours are the monthly median (maximum) of a, c June–August and b, d non June–August 1-year ice age extent from the a, b 1989–1998 median (maximum) and c, d 2014–2023 median (maximum) ice age extent. Composites in e, f are averaged relative to the e VRILE location and f closest Arctic cyclone with dashed (solid) contours indicating negative (positive) anomalies.

To conclude, SIE has been objectively identified to exhibit significant, short, “weather”, timescale variability at periods of 18 days or less in the Arctic. The times of the extreme reductions in SIE corresponding to these short timescale variations, referred to as VRILEs, or VRILEs, are found to occur throughout the year, with a significant increase in the frequency of VRILEs since 1979 during the warm season from June-August. The locations of VRILEs are located over an extensive region of 1st-year Arctic sea ice during the warm season but is confined to the MIZs of the North Atlantic, Bering Sea, and Sea of Okhotsk outside of the warm season. Furthermore, the locations of the VRILEs are in regions of strong low-level atmospheric horizontal pressure gradients that are enhanced between Arctic cyclones and the Beaufort High. The Arctic cyclones are accompanied by an antecedent TPV. TPVs can be present days to weeks before the formation of a surface cyclone63,70,71, and yet are located in atmospheric layers that are exceptionally devoid of reliable observations, particularly moisture, which has been shown to be important for TPV maintenance and intensification77. This, combined with the relatively low forecast skill of some Arctic cyclones36, suggests that TPVs may be an important feature of interest in improving the predictability of sea ice loss at up to seasonal timescales. Note that while a number of studies have established a link between Arctic cyclones and sea ice24,25,26,27,34,78, this is the first study to establish the association to enhanced pressure gradients over thin sea ice. Thus, this study has proposed a distinction for Arctic cyclones that lead to sea ice loss versus those that do not. Furthermore, this study is the first to establish a connection to TPVs. Given these new insights, future studies are needed to address the underlying physical mechanisms causing VRILEs.

Methods

We use daily SIE from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Sea Ice Index79. Before 1989, SIE is only available every second day. Given that this study focuses on day-to-day variations in SIE, we restrict the analysis to the years 1989–2023 when SIE is available daily. ΔSIE is the 3-day change in SIE, i.e, SIE(n + 1) − SIE(n − 2), where n = day. Due to sudden, erroneous jumps in SIE that occur on the first day of every month80, we omit any analysis of ΔSIE on the last 2 days and first day of each month. These sudden jumps were found to occur due to the difference in ocean masks used in the Arctic to filter residual weather effects far from the ice edge where sea ice is not possible, and these ocean masks are only updated once a month on the first day of each month.

Two different methods of quantifying ΔSIE for short-time scale variability are considered here: Extremes of all (1) ΔSIE from daily SIE anomalies with respect to a daily SIE climatological mean annual cycle for 1990–2018 (ΔSIEmean removed), and (2) spectrally filtered ΔSIE using a high-pass Butterworth Filter using a cutoff period of 18 days to isolate the short timescale variability that can generally be interpreted as “weather” (ΔSIEbwfilt). Extremes are treated as the tail of the distribution of ΔSIE loss, here the lowest 5th-percentile in ΔSIE. Method (1) can be interpreted as the extreme ΔSIE events based on the anomalies in ΔSIE with respect to the long-term climatological record. While neither method above is expected to be a perfect measure of ΔSIE, both methods have merits and shortcomings. Method (1) identifies all extreme instances of SIE loss; however, variability from processes at all timescales is implicitly included. For example, sea ice melt may be enhanced during the negative phase of the AO, when near-surface temperatures are anomalously warm and cloud cover is less likely. Even though SIE could decrease substantially over a short duration of time (days), the frequency of such “events” is relatively low (months), and method (1) can not distinguish the two scales apart. In contrast, method (2) explicitly removes variability associated with long-term climate trends, seasonal oscillations, as well as intraseasonal variations. Method (2) emphasizes the relatively short timescale variability in ΔSIE that could occur on synoptic (“weather”) timescales from atmospheric processes, including Arctic cyclones and their associated fronts. By definition, method (2) isolates the events associated with the short timescales that have significant variability in observations, and that may be missing from climate models. The union of events from both methods (1) and (2) using ΔSIEtotal are the total VRILEs. ΔSIEtotal is the sum of ΔSIEmean removed and ΔSIEbwfilt. When both methods capture the same event, the event is added individually to both ΔSIEmean removed and ΔSIEbwfilt, but only one event is added to ΔSIEtotal. The fractional SIE reduction per warm season from ΔSIEtotal is computed by comparing the daily ΔSIEtotal accumulated on all respective dates from 1 June - 31 August, and dividing by the daily ΔSIE accumulated each day from 1 June to 31 August:

Occurrences of VRILEs on consecutive days are not eliminated but are recognized as possibly being related to the same physical feature, such as a long-lived surface cyclone. To account for these occurrences, we reduce the VRILEs into a subset referred to as “Unique VRILEs”, where any series of VRILEs identified on adjacent days are counted as a single event, with the date corresponding to the last day in the series. VRILEs are increasing in frequency during the warm season, regardless of whether daily back-to-back VRILEs are counted (“Unique cases”) or if the tail of the extreme distributions is relaxed to the 10th-percentile (not shown). Trends of unique VRILES are weaker while remaining significant. Since atmospheric patterns between consecutive days are generally correlated, we include only unique VRILEs in our analysis to reduce the possibility of biasing the spatial statistics to less common, long-lived atmospheric features.

Power spectral density (PSD) is computed from the daily ΔSIE timeseries by subtracting the mean and computing the absolute value of the square of the Fast Fourier Transform coefficient. Statistical significance is established at the 95% confidence level by comparing the computed power spectra against the theoretical red noise spectrum using the lag correlation function for a first-order linear Markov process with a one-lag autocorrelation81.

ΔSIE does not contain information about the specific geographic location of a VRILE. In order to map the VRILE to a location to analyze composite patterns, we compute the change in daily NSIDC sea ice concentration (SIC) over a 5-day period ending on the day of the VRILE. The resulting changes in SIC are then separated into objects by comparing grid point changes with each of the neighboring grid points. The largest connected region of loss is then identified as the VRILE object. The single point location of the VRILE is determined by computing the center of mass where all points within the ice loss object are weighted by the absolute value of the 5-day SIC change. Atmospheric fields from the day of the VRILE are then averaged relative to the location of the VRILE using European Center for Medium Range Forecasting Reanalysis (ERA5)82. The nearest surface cyclone is found as long as it is within 1500 km of the VRILE location up to 5 days before the VRILE. The nearest TPV is used as the reference point for the TPV-relative composites. Surface cyclones and TPVs are identified by local minima in their respective fields. Composite anomalies of sea level pressure and tropopause potential temperature are computed from ERA5 with respect to the 30-year monthly mean from 1981–2010. Composite plots are oriented such that the lowest value of tropopause potential temperature in the TPV lies at the center point.

Data availability

The sea ice extent data that support the findings of this study are available online from https://nsidc.org/data/g02135/versions/3. NOAA/NSIDC Climate Data Record of Passive Microwave Sea Ice Concentration used in this study can be downloaded online from https://nsidc.org/data/g02202/versions/4. EASE-Grid Sea Ice Age is available from the NSIDC at https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0611/versions/4. ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis data are available for download at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview.

Code availability

The code to create the VRILE data and the corresponding plotting scripts used to produce the figures and table data in this article is available on Zenodo83 and can be accessed via this link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14517274.

References

Solomon, S. et al. Climate Change 2007-the Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC, vol. 4 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Blunden, J. & Arndt, D. S. State of the climate in 2012. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 94, S1–S238 (2013).

Simmonds, I. & Li, M. Trends and variability in polar sea ice, global atmospheric circulations, and baroclinicity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1504, 167–186 (2021).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Stroeve, J. & Notz, D. Changing state of Arctic sea ice across all seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 103001 (2018).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Natgeo 7, 181–184 (2014).

Arrhenius, S. On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground. Lond. Edinb., Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 41, 237–276 (1896).

Hall, A. The role of surface albedo feedback in climate. JCE 17, 1550–1568 (2004).

Serreze, M. C. & Francis, J. A. The Arctic amplification debate. Clim. Chang. 76, 241–264 (2006).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Crook, J. A., Forster, P. M. & Stuber, N. Spatial patterns of modeled climate feedback and contributions to temperature response and polar amplification. jce 24, 3575–3592 (2011).

Taylor, P. C. et al. A decomposition of feedback contributions to polar warming amplification. J. Clim. 26, 7023–7043 (2013).

Lee, S., Gong, T., Feldstein, S. B., Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Revisiting the cause of the 1989-2009 Arctic surface warming using the surface energy budget: downward infrared radiation dominates the surface fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10–654 (2017).

Jahn, A., Kay, J. E., Holland, M. M. & Hall, D. M. How predictable is the timing of a summer ice-free Arctic? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9113–9120 (2016).

Barnhart, K. R., Miller, C. R., Overeem, I. & Kay, J. E. Mapping the future expansion of Arctic open water. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 280–285 (2016).

Swart, N. C., Fyfe, J. C., Hawkins, E., Kay, J. E. & Jahn, A. Influence of internal variability on Arctic sea-ice trends. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 86 (2015).

Notz, D. & Community, S. Arctic sea ice in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086749 (2020).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Donohoe, A., Roach, L. A., DuVivier, A. & Bitz, C. M. High-frequency sea ice variability in observations and models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL092356 (2021).

Simmonds, I. & Rudeva, I. The great Arctic cyclone of August 2012. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L23709 (2012).

Parkinson, C. L. & Comiso, J. C. On the 2012 record low Arctic sea ice cover: combined impact of preconditioning and an August storm. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1356–1361 (2013).

Zhang, J., Lindsay, R., Schweiger, A. & Steele, M. The impact of an intense summer cyclone on 2012 Arctic sea ice retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 720–726 (2013).

Kriegsmann, A. & Brümmer, B. Cyclone impact on sea ice in the central Arctic Ocean: a statistical study. Cryosphere 8, 303–317 (2014).

Yamagami, A., Matsueda, M. & Tanaka, H. L. Extreme Arctic cyclone in August 2016. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 18, 307–314 (2017).

Wang, Z., Walsh, J., Szymborski, S. & Peng, M. Rapid Arctic sea ice loss on the synoptic time scale and related atmospheric circulation anomalies. J. Clim. 33, 1597–1617 (2020).

Schreiber, E. A. & Serreze, M. C. Impacts of synoptic-scale cyclones on Arctic sea-ice concentration: a systematic analysis. Ann. Glaciol. 61, 139–153 (2020).

Clancy, R., Bitz, C. M., Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., McGraw, M. C. & Cavallo, S. M. A cyclone-centered perspective on the drivers of asymmetric patterns in the atmosphere and sea ice during Arctic cyclones. J. Clim. 35, 73–89 (2022).

Finocchio, P. M., Doyle, J. D. & Stern, D. P. Accelerated sea-ice loss from late-summer cyclones in the new Arctic. J. Clim. 35, 7751–7769 (2022).

Marko, J. R. Observations and analyses of an intense waves-in-ice event in the Sea of Okhotsk. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 108. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2001JC001214 (2003).

Asplin, M. G., Galley, R., Barber, D. G. & Prinsenberg, S. Fracture of summer perennial sea ice by ocean swell as a result of Arctic storms. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 117. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2011JC007221 (2012).

Asplin, M. G. et al. Implications of fractured Arctic perennial ice cover on thermodynamic and dynamic sea ice processes. JGR Oceans 119, 2327–2343 (2014).

Stopa, J. E., Ardhuin, F. & Girard-Ardhuin, F. Wave climate in the Arctic 1992-2014: seasonality and trends. Cryosphere 10, 1605–1629 (2016).

Squire, V. A. Ocean wave interactions with sea ice: a reappraisal. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 52, 37–60 (2020).

Waseda, T., Nose, T., Kodaira, T., Sasmal, K. & Webb, A. Climatic trends of extreme wave events caused by Arctic Cyclones in the western Arctic Ocean. Polar Sci. 27, 100625 (2021).

Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E., Webster, M., Boisvert, L., Parker, C. & Horvat, C. Record Arctic Cyclone of January 2022: Characteristics, Impacts, and Predictability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD037161 (2022).

Jung, T. & Matsueda, M. Verification of global numerical weather forecasting systems in polar regions using TIGGE data. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 142, 574–582 (2016).

Yamagami, A., Matsueda, M. & Tanaka, H. L. Medium-range forecast skill for extraordinary arctic cyclones in summer of 2008-2016. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4429–4437 (2018).

Capute, P. K. & Torn, R. D. A comparison of Arctic and Atlantic cyclone predictability. Mon. Weather Rev. 149, 3837–3849 (2021).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627 (2014).

Walsh, J. E. Intensified warming of the Arctic: causes and impacts on middle latitudes. Glob. Planet. Chang. 117, 52–63 (2014).

Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surv. Geophys. 35, 1175–1214 (2014).

Overland, J. E. A difficult Arctic science issue: midlatitude weather linkages. Polar Sci. 10, 210–216 (2016).

Screen, J. A. et al. Consistency and discrepancy in the atmospheric response to Arctic sea-ice loss across climate models. Nat. Geosci. 11, 155–163 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Anchoring of atmospheric teleconnection patterns by Arctic Sea ice loss and its link to winter cold anomalies in East Asia. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 547–558 (2021).

Overland, J. E. et al. How do intermittency and simultaneous processes obfuscate the Arctic influence on midlatitude winter extreme weather events? Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 043002 (2021).

Rudeva, I. & Simmonds, I. Midlatitude winter extreme temperature events and connections with anomalies in the Arctic and tropics. J. Clim. 34, 3733–3749 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Extreme cold events from East Asia to North America in winter 2020/21: comparisons, causes, and future implications. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 553–565 (2022).

Gervais, M., Sun, L. & Deser, C. Impacts of projected Arctic sea ice loss on daily weather patterns over North America. J. Clim. 37, 1065–1085 (2024).

Luo, D. et al. Arctic amplification-induced intensification of planetary wave modulational instability: a simplified theory of enhanced large-scale waviness. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 2888–2905 (2024).

Lawrence, D. M., Slater, A. G., Tomas, R. A., Holland, M. M. & Deser, C. Accelerated Arctic land warming and permafrost degradation during rapid sea ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 11506 (2008).

Holland, M. M., Bitz, C. M. & Tremblay, B. Future abrupt reductions in the summer Arctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23503 (2006).

Stroeve, J., Hamilton, L. C., Bitz, C. M. & Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. Predicting September sea ice: ensemble skill of the SEARCH sea ice outlook 2008–2013. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2411–2418 (2014).

Stroeve, J. et al. Improving predictions of Arctic sea ice extent. EOS 96 (2015).

Screen, J. A., Simmonds, I. & Keay, K. Dramatic interannual changes of perennial Arctic sea ice linked to abnormal summer storm activity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D15105 (2011).

Finocchio, P. M., Doyle, J. D., Stern, D. P. & Fearon, M. G. Short-term impacts of Arctic summer cyclones on sea ice extent in the marginal ice zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088338 (2020).

Taylor, P. C., Kato, S., Xu, K.-M. & Cai, M. Covariance between Arctic sea ice and clouds within atmospheric state regimes at the satellite footprint level. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 12656–12678 (2015).

Valkonen, E., Cassano, J. & Cassano, E. Arctic cyclones and their interactions with the declining sea ice: a recent climatology. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD034366 (2021).

Williams, T. D., Bennetts, L. G., Squire, V. A., Dumont, D. & Bertino, L. Wave-ice interactions in the marginal ice zone. Part 1: Theoretical foundations. Ocean Model. 71, 81–91 (2013).

Collins, C. O., Rogers, W. E., Marchenko, A. & Babanin, A. V. In situ measurements of an energetic wave event in the Arctic marginal ice zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1863–1870 (2015).

Strong, C. & Rigor, I. G. Arctic marginal ice zone trending wider in summer and narrower in winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4864–4868 (2013).

Screen, J. A., Bracegirdle, T. J. & Simmonds, I. Polar climate change as manifest in atmospheric circulation. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 4, 383–395 (2018).

Aizawa, T. & Tanaka, H. L. Axisymmetric structure of the long lasting summer Arctic cyclones. Polar Sci. 10, 192–198 (2016).

Serreze, M. C. & Barrett, A. P. The summer cyclone maximum over the central Arctic Ocean. J.Clim. 21, 1048–1065 (2008).

Cavallo, S. M. & Hakim, G. J. Potential vorticity diagnosis of a tropopause polar cyclone. Mon. Weather Rev. 137, 1358–1371 (2009).

Simmonds, I. & Rudeva, I. A comparison of tracking methods for extreme cyclones in the Arctic basin. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 66, 25252 (2014).

Tao, W., Zhang, J. & Zhang, X. The role of stratosphere vortex downward intrusion in a long-lasting late-summer Arctic storm. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 143, 1953–1966 (2017).

Tao, W., Zhang, J., Fu, Y. & Zhang, X. Driving roles of tropospheric and stratospheric thermal anomalies in intensification and persistence of the Arctic Superstorm in 2012. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10017–10025 (2017).

Gray, S. L., Hodges, K. I., Vautrey, J. L. & Methven, J. The role of tropopause polar vortices in the intensification of summer Arctic cyclones. Weather Clim. Dyn. 2, 1303–1324 (2021).

Ban, J., Liu, Z., Bromwich, D. H. & Bai, L. Improved regional forecasting of an extreme Arctic cyclone in August 2016 with WRF MRI-4DVAR. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 149, 3490–3512 (2023).

Qian, Q., Zhong, W., Yao, Y. & Zhang, D. Influence of the thermal structure on the intensification of the extreme arctic cyclone in August 2016. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD038638 (2023).

Cavallo, S. M. & Hakim, G. J. The composite structure of tropopause polar cyclones from a mesoscale model. Mon. Weather Rev. 138, 3840–3857 (2010).

Bray, M. T. & Cavallo, S. M. Characteristics of long-track tropopause polar vortices. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 251–278 (2022).

Kay, J. E. et al. The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. BAMS 96, 1333–1349 (2015).

Rigor, I. G., Wallace, J. M. & Colony, R. L. Response of sea ice to the Arctic Oscillation. JCE 15, 2648–2663 (2002).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. Sea ice response to an extreme negative phase of the Arctic Oscillation during winter 2009/2010. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L02502 (2011).

Ogi, M., Rysgaard, S. & Barber, D. G. Importance of combined winter and summer Arctic Oscillation (AO) on September sea ice extent. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 034019 (2016).

Kwok, R. Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958-2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 105005 (2018).

Cavallo, S. M. & Hakim, G. J. The physical mechanisms of tropopause polar cyclone intensity change. J. Atmos. Sci. 70, 3359–3373 (2013).

Lukovich, J. V. et al. Summer extreme cyclone impacts on Arctic sea ice. J. Clim. 34, 4817–4834 (2021).

Fetterer, F., Knowles, K., Meier, W. & Savoie, M. Sea ice index. National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, CO, accessed 2 August 2024; Available at https://noaadata.apps.nsidc.org/NOAA/G02135/ (2002).

Meier, W. N. & Stewart, J. S. Assessing uncertainties in sea ice extent climate indicators. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 035005 (2019).

Gilman, D. L., Fuglister, F. J. & Mitchell Jr, J. M. On the power spectrum of “red noise”. J. Atmos. Sci. 20, 182–184 (1963).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Cavallo, S., Bitz, C. & Frank, M. Code for Nature Comms. Env. “Sea ice loss in association with Arctic cyclones”. https://zenodo.org/records/14517274 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Office of Naval Research (ONR) for support of this research under ONR grants N00014-16-1-2489 and N00014-18-1-2223 (SMC and MCF), N00014-18-1-2175 and N00014-21-1-2490 (CMB), as well as National Science Foundation (NSF) grants PLR-2141537 (SMC) and PLR-2141538 (CMB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Cavallo, M. Frank, and C. Bitz conceptualized the research. S. Cavallo designed the methodology. S. Cavallo conducted the main portion of the literature review and all authors contributed to it. S. Cavallo analyzed the input data. S. Cavallo performed the formal analysis, with many contributions from M. Frank and C. Bitz. All authors contributed to the investigation and interpretation. S. Cavallo drafted the paper. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Seung-Ki Min and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavallo, S.M., Frank, M.C. & Bitz, C.M. Sea ice loss in association with Arctic cyclones. Commun Earth Environ 6, 44 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02022-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02022-9

This article is cited by

-

Antarctic haze phenomena at Syowa Station, Antarctica: seasonal features and impacts on atmospheric chemistry

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)