Abstract

Tropical forests enhance regional rainfall but a robust analysis of this benefit is lacking. Consequently, the rainfall generating services of tropical forests are rarely accounted for in policymaking. We synthesised observational and model-based values of the reduction in rainfall due to tropical deforestation to quantify rainfall generation. Across these studies, we estimate that each meter squared of forest contributes 240 ± 60 L each year to regional rainfall. The Amazon forest has an even stronger rainfall benefit, with each meter squared of forest contributing 300 ± 110 L each year. Using a simple approach that assumes a constant water unit price, we estimate that Amazon forest rainfall generation is worth US$59.40 per hectare annually and the Brazilian Legal Amazon delivers rainfall generation worth US$20 ± 7 billion annually. Recognizing the economic value of tropical forests’ rainfall provision will unlock crucial investment and transform policy discussions on payments for forest protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

International aspirations to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030 (e.g. the New York Declaration on Forests, 2014, 26th Conference of the Parties Glasgow Leaders Declaration on Forests, 2021) have led to limited action. Concrete evidence of the benefits forests provide at local and regional scales could transform how forests are valued and deliver a step-change in efforts to protect and restore them. Economic estimates of forest ecosystem services are available1,2,3, but they do not always include the regional climate services of forests. There is now strong evidence of the mechanistic link between tropical deforestation and reduced rainfall, principally through reduced evapotranspiration reducing atmospheric moisture4. Despite this, the magnitude of rainfall reduction is uncertain and the economic value of tropical forests’ maintenance of regional rainfall remains poorly quantified.

An analysis of the impact of Brazil deforestation on agricultural production estimated that deforestation-driven rainfall reductions could contribute agricultural losses of up to US$ 1 billion annually5. This estimate was based on modelled projections of future land-use under weak environmental governance resulting in 56% Amazon forest loss by 2050. This result highlights that the benefits of forest conservation may far outweigh any opportunity costs but was based on a single model and a worst-case vision for the future. Spatially explicit estimates of the ecosystem services provided by the Brazilian Amazon identified rent losses to soybean, beef and hydroelectricity production totalling US$7.56 ha−1 yr−1 due to reduced rainfall from deforestation1. In 2024, a white paper on the importance of rainfall generation from forests in Brazilian indigenous territories was submitted to the Brazil Supreme Court6. The authors used a moisture tracking model to calculate the contribution of evaporation from indigenous forests to rainfall elsewhere in Brazil. They reported the total agricultural income from Brazilian states most dependent on rain from Amazon forests as US$61 billion. The range in these model-based estimates highlights a clear policy need to constrain the value of forest-generated rainfall at national and regional scales. Furthermore, until now economic valuations of the rainfall-generating services of tropical forests have been based on evaluation of scarce model simulations and observational constraints have been entirely lacking.

Here, for the first time, we synthesise simulations from the latest generation of climate models with data from satellite observations to make a more robust estimate of the rainfall generating services of tropical forests. We then make a simple estimate of the economic benefits of Amazon forests in sustaining regional rainfall to inform land-use and policy decisions.

Quantifying the rainfall generation services of tropical forests

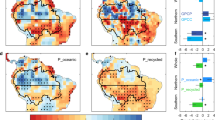

We synthesised new and existing model-based estimates of the impacts of tropical deforestation on regional rainfall with results from a pantropical analysis of satellite observations (Methods, Table 1). We analysed idealised deforestation simulations from 11 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6) models contributing to the Land Use Model Intercomparison Project (LUMIP). These models simulated a multi-model mean rainfall reduction of –2.0 ± 1.5 mm year−1 per percentage point of tropical forest loss (Table 1). This value is highly consistent with the rainfall sensitivity to tropical forest loss estimated from simulations of historical deforestation: across 24 CMIP6 models the mean response was a –2.2 ± 0.8 mm year−1 reduction in rainfall per percentage point of tropical forest loss7. Notably, these two approaches include different deforestation extents, but result in a similar sensitivity of rainfall to forest loss. We compared these model-based estimates with a recent analysis of ten satellite-derived precipitation products8. Observations suggest a higher sensitivity of rainfall to tropical deforestation than indicated by models, with a –3.0 ± 1.2 mm year−1 reduction in rainfall per percentage point of tropical forest loss over a surrounding 200 km × 200 km (40,000 km2) area. Our best estimate of the impacts of deforestation (tested with several forest loss datasets in Fig. S1) on rainfall, calculated as the inverse-weighted mean across model-based and observational estimates (±mean across errors), is –2.4 ± 0.6 mm year−1 per percentage point of tropical forest loss.

We used these values to estimate the annual volume of rainfall generated per m2 of tropical forest. We estimate a rainfall reduction of –240 million L per year for each 1 km2 forest loss, or –240 ± 60 L per year per m2 of forest loss. That is, each m2 of tropical forest contributes around 240 L of rainfall to the surrounding region per year. For the Amazon, we included a metanalysis of Amazon deforestation simulations from regional and global climate models9. The synthesised rainfall response to Amazon deforestation across models and observations was larger than for the Pantropics, at –3.0 ± 1.1 mm year−1 (Table 1). This translates to each m2 of Amazon forest producing 300 ± 110 L of water per year. This value is consistent with estimates of Amazon evapotranspiration of ~1100 L m−2 year−1, with around a third of this contributing to regional rainfall10.

To put rainfall generation in context, we consider the annual water demands of four key crops11, which account for 70% of the harvested area in Brazil (Table 2). At the upper end of crop water consumption, cotton and soybean use 607 L m–2 and 501 L m–2 per year, equal to the amount of water produced by 2.0 and 1.7 m2 of intact forest, respectively. At the lower end, rainfed wheat uses 285 L m–2, or the amount of water produced by 0.95 m2 of intact forest. These values provide an illustration of the amount of forested land required to meet agricultural water demands, with up to twice as much forest required per unit area of crop.

Estimating the economic benefit of forests through rainfall provision

Estimates of the economic value of rainfall generation are of interest to landowners and policymakers. A report from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and the National Water Agency (ANA) estimated the average cost of water in the Brazilian agricultural sector as R$0.11 m−3 or around US$0.0198 m−312. Using this value, we calculated that the rainfall produced per m2 of Amazon forest (Table 1) is worth approximately US$0.00594 (US$0.0198 × 0.3 m3), which equates to a monetary value of $59.40 ± 21.78 per hectare of tropical forest.

We demonstrate the potential economic value of rainfall creation for the Brazil Legal Amazon which covers 330 million hectares by multiplying the area of the Amazon forest by our estimated per hectare value. Using this simple approach, we estimate the Brazilian Legal Amazon provides rainfall generation services worth US$19.6 ± 7 billion annually. A recent World Bank report estimated the value of water regulation services in the Brazil Legal Amazon at US$8.7 billion13, less than half our estimate.

Over 220 million hectares of the Brazilian Amazon has been allocated for conservation, through Brazil’s protected area system. We estimate this provides rainfall generation worth US$13 ± 5 billion annually, more than 50 times the budget allocated to the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment (MMA) for protected area management. At a regional level, protected areas in Mato Grosso and Rondônia provide an annual rainfall generation worth $1.1 billion and $0.7 billion, respectively. Indigenous lands comprise 110 million hectares across the Brazilian Amazon and contribute US$6.5 billion annually through rainfall generation.

Agriculture contributes US$150 billion to Brazil’s GDP annually, and with 85% of Brazil’s agriculture being rainfed, reliable rainfall is crucial. Reduced rainfall and delays in wet season onset have impacted soy and maize crops in Brazil, with greater rainfall reductions in regions with greater forest loss14. We estimate that deforestation over recent decades, totalling 80 million hectares, has reduced the rainfall-generating service of Brazil’s Amazon forests by US$4.8 billion annually, representing a substantial loss to Brazil’s economy. Reduced rainfall as a consequence of deforestation also has implications for clean water access15, navigability between remote settlements16, hydropower production17,18 and carbon storage of remaining tropical forests19. The financial risks of complete Amazon forest loss, caused by deforestation and climate change triggering catastrophic ecosystem collapse, has previously been estimated at between US$0.96 trillion and US$3.6 trillion over a 30-year period20, equivalent to US$120 billion per year.

Structuring financial incentives for tropical forest protection

Valuing the ecosystem services provided by forests could provide incentives to slow deforestation. However, incentives need to be sufficiently large, which may require stacking financial instruments, and capital must reach the stakeholders and practitioners that need it. Recent developments have started to link financial payments to environmental outcomes, including reducing deforestation and forest restoration. In August 2024, the World Bank issued the Amazon Reforestation-Linked Outcome Bond, a 9-year US$ 225 million bond, which mobilises capital to support reforestation activities. In 2023, Brazil raised $2 billion through its first-ever ‘green’ bond issuance. While these are encouraging steps, the payments only amount to around a tenth of the annual value provided by the Amazon’s rainfall generation services and are likely insufficient to significantly slow deforestation.

New innovative approaches are needed to stimulate private capital, including public-private partnerships, to ensure appropriate risk management and equitable risk sharing among investors. Such ‘blended finance’ models involving private, public and philanthropic investment have been trialled in the Amazon to support forest conservation21. Private companies in the deforestation supply chain are positioned to provide substantial capital investment to improve the sustainability of their products and support their long-term commercial viability. However, private investors are often unwilling to sacrifice investment returns, which may be lower than traditional investments. Involving national governments and non-governmental organisations can mitigate risk on investment returns, potentially making forest conservation and restoration initiatives more attractive to private investors. Reconciling the competing motivations of different stakeholders can be challenging21, but this approach can allow them all to achieve their goals.

There have been some recent cases of success. The Responsible Commodities Facility, a partnership between several UK supermarkets and banks, offers Brazilian soy farmers favourable financing for their operations in return for not clearing native forests. Agri 3, a blended finance fund, has also seen successful deployment of capital in Brazil across numerous commodities and regions. The Brazilian stock exchange, B3, is also making positive steps towards formalising novel carbon markets into their exchange, which will direct investment into afforestation and avoided deforestation. The Brazil-led Tropical Forest Forever Facility, a blended-finance mechanism designed to value the ecosystem services provided by tropical forests, aims to raise $125 billion and use investment returns to reward countries for conserving tropical forests through fixed annual payments of $4 per hectare of standing forest. Our work provides new evidence of the rainfall generation services of tropical forests that supports such financial approaches to forest protection.

Challenges and research needs

Our study provides a new estimate of the sensitivity of rainfall to tropical forest loss and demonstrates consistent results across different modelling and empirical approaches. Nonetheless, substantial inter-model variability remains, driven in part by uncertainties in the simulated atmospheric response to deforestation22. Emerging higher-resolution modelling frameworks23,24,25 offer promising avenues, though it is not yet clear whether they yield more realistic representations of the observed impacts of deforestation. We have presented a relatively simple economic valuation of this important rainfall-regulation service. Future research should integrate our new rainfall estimates with more sophisticated economic approaches1 to refine this valuation.

Tropical deforestation continues26 despite global commitments to reduce forest loss. Careful management of land in deforested landscapes can support the health of remaining forest ecosystems27, though rainfall generation services provided by tropical forests are largely unrecognised. This service operates at local to regional scales, affecting areas ranging from tens to thousands of kilometres. Given the vital importance of reliable rainfall for tropical agriculture, recognising this connection between forests and rainfall could help ease tensions between forest and agricultural interests, fostering greater bipartisan support for forest conservation.

Methods

We estimated annual rainfall change due to deforestation based on analysis of LUMIP output synthesised with existing results from observations and regional and global climate model. We used values from published literature7,8,9 and new analysis of model simulations from the 6th Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6). Our estimate accounts for the differing uncertainty in these estimates by calculating the inverse-variance weighted mean.

CMIP6 LUMIP simulations

We downloaded and processed CMIP6 simulations28 from the Earth System Grid Federation (https://esgf-ui.ceda.ac.uk/cog/search/cmip6-ceda/). We used the preindustrial control (piControl) and global deforestation (deforest-globe) simulations. The latter is an idealised deforestation experiment whereby 20 million km2 of forest is linearly converted to grassland over a 50-year period (i.e. 0.4 million km2 forest loss per year). For 11 LUMIP models we downloaded precipitation data from the piControl and deforest-globe simulations. Following22, we calculated the precipitation response to deforestation by subtracting the first 30 years of the piControl run from the last 30 years of the deforest-globe run. We also downloaded tree fraction data and calculated the percentage reduction in forest cover. For the two models that did not output tree fraction data (GISS-E2-1-G and MIROC-ES2L), we used the mean tree fraction change across the other nine models to estimate the precipitation change per percentage point of forest loss. We calculated the mean response across models (n = 7) that captured the same sign of rainfall response to the observations (i.e. a reduction in rainfall with forest loss). We used Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Land Cover Type (MCD12Q1) version 6.1 310 downloaded from https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ to constrain our analysis to evergreen broadleaf tropical forests in the Amazon and pantropical regions.

CMIP6 historical simulations

The pantropical annual rainfall response to deforestation based on historical CMIP6 simulations with realistic land cover change from 24 global climate models is −0.18 ± 0.07 mm month−1 %−17. This is equivalent to –2.16 ± 0.84 mm year−1 %−1.

Satellite observations

The first pantropical analysis of the impact of deforestation on rainfall based on satellite observations (n = 10) reported a monthly rainfall response of –0.25 ± 0.1 mm %−1 at 2° horizontal resolution (~200 km × 200 km at the Equator)8. This is equivalent to –3.0 ± 1.2 mm %−1 at the annual scale. Converting from millimetres to metres and multiplying across the area of an entire grid cell (4 × 1010 m2), gives a volume of 1.2 × 108 ± 4.8 × 107 m3 annual rainfall reduction for one percentage point of forest loss. One percent of a 200 km × 200 km grid cell represents 400 km2, thus we can compute the annual rainfall change per km2 of forest loss as –1.2 × 108 m3/400 km2 = –300,000 ± 120,000 m3 km−2. Considering there are 1000 L per m3, this represents a rainfall reduction of –300 million L per year for each 1 km2 forest loss, or –300 L per year per m2 of forest loss. We also tested the sensitivity of the satellite-derived estimate to uncertainty in detected forest loss. In addition to the Global Forest Change dataset used in8, we also examined the GLAD, ESA and MapBiomas forest loss products (Supplementary Fig. 1). Mean forest loss across the Amazon during 2001–2020 was greatest in the GFC product. This suggests our estimated sensitivity of rainfall to forest loss is a lower estimate.

Metanalysis of regional and global climate models

A synthesis of regional and global climate modelling studies (n = 96) estimated a relative rainfall response per percentage point of deforestation of –0.16 ± 0.13% %−1 9. Assuming observed annual mean rainfall in the Amazon is 2333 mm year (mean across 18 publications synthesised by ref. 29 this would equate to a rainfall change due to forest loss of –3.73 ± 3.0 mm year−1 %−1.

In all studies, we calculate the sensitivity of precipitation to forest loss by dividing the precipitation change by the forest loss, thus implicitly assuming a linear relationship between forest loss and precipitation. This assumption is supported by evidence from observations8 and models, with a similar sensitivity in model simulations of smaller forest loss from historical simulations (–2.1 ± 0.8 mm %−1) compared to larger scale and idealised forest loss (–2.0 ± 1.5 mm %−1).

Financial calculations

When estimating the annual value of rainfall creation for an area, we multiply the area in hectares by the annual change in rainfall due to the area’s deforestation in m3, the conversion of m2 to hectares and the average cost of water in the area. In the Brazilian Legal Amazon, therefore, the calculation is 300 Mha × 0.3 m3 × 10,000 × US$0.0198 m−3 which generates US$19.7 billion.

Data availability

All data used in the analysis are publicly available. CMIP6 historical and LUMIP available to download from: https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc/cmip6/data/CMIP6. Land cover data are from the following publicly available repositories; GFC (https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-change). GLAD. ESA-CCI (https://www.esa-landcover-cci.org/). Mapbiomas (https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/en/downloads/). Satellite observations used in ref. 8 are freely available to download from the following repositories: CHIRPS from https://data.chc.ucsb.edu/products/?C = M;O = D. CMORPH from https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/precip/CMORPH_RT/GLOBE/data/. CPC from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html. CRU from https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/. ERA5 from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview. GPCC from https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/GPCC/html/download_gate.html. GPCP from https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/GPCPMON_3.2/summary?keywords=GPCPMON_3.2. GPM from https://gpm1.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/data/GPM_L3/. JRA from https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/jra-55 and https://jra.kishou.go.jp/JRA-55/index_en.html. MERRA-2 from https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets?project=MERRA-2. NOAA (PREC/LAND) from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.precl.html. PERSIANN (CCS, CDR, CCS-CDR, PDIR-NOW) from https://chrsdata.eng.uci.edu/. TRMM from https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/TRMM_3B43_7/summary. UDEL from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.UDel_AirT_Precip.html. Crop water usage data is available from ref. 11. Model meta-analysis data and information accessible within9.

References

Strand, J. et al. Spatially explicit valuation of the Brazilian Amazon forest’s ecosystem services. Nat. Sustain. 1, 657–664 (2018).

Taye, F. A. et al. The economic values of global forest ecosystem services: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 189, 107145 (2021).

de Groot, R. et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst. Serv. 1, 50–61 (2012).

Spracklen, D. V, Baker, J. C. A., Garcia-Carreras, L. & Marsham, J. H. Annual review of environment and resources the effects of tropical vegetation on rainfall. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ (2018).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Soares-Filho, B. S., Davis, J. L., Abrahão, G. M. & Börner, J. Deforestation reduces rainfall and agricultural revenues in the Brazilian Amazon. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Mattos, C. et al. Manutenção Das Terras Indígenas é Fundamental Para a Segurança Hídrica e Alimentar Em Grande Parte Do Brasil. Nota técnica. Instituto Serrapilheira (2024).

Smith, C. et al. Observed and simulated local climate responses to tropical deforestation. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 104004 (2023).

Smith, C., Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 615, 270–275 (2023).

Spracklen, D. V. & Garcia-Carreras, L. The impact of Amazonian deforestation on Amazon basin rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9546–9552 (2015).

Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Divergent representation of precipitation recycling in the Amazon and the Congo in CMIP6 models. Geophys Res Lett. 49, e2021GL095136 (2022).

Flach, R. et al. Water productivity and footprint of major Brazilian rainfed crops—a spatially explicit analysis of crop management scenarios. Agric Water Manag 233, 105996 (2020).

IBGE. Contas Econômicas Ambientais Da Água: Brasil. https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/multidominio/meio-ambiente/20207-contas-economicas-ambientais-da-agua-brasil.html?=&t=sobre (2023).

Hanusch, M. A Balancing Act for Brazil’s Amazonian States: An Economic Memorandum. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/39778 (2023).

Leite-Filho, A. T., Soares-Filho, B. S., Oliveira, U. & Coe, M. Intensification of climate change impacts on agriculture in the Cerrado due to deforestation. Nat. Sustain 8, 34–43 (2025).

Mapulanga, A. M. & Naito, H. Effect of deforestation on access to clean drinking water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 8249–8254 (2019).

Santos de Lima, L. et al. Severe droughts reduce river navigability and isolate communities in the Brazilian Amazon. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–12 (2024).

Stickler, C. M. et al. Dependence of hydropower energy generation on forests in the Amazon Basin at local and regional scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9601–9606 (2013).

Araujo, R. The value of tropical forests to hydropower. Energy Econ. 129, 107205 (2024).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature 595, 388–393 (2021).

Lapola, D. M. et al. Limiting the high impacts of Amazon forest dieback with no-regrets science and policy action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 11671–11679 (2018).

Rode, J. et al. Why ‘blended finance’ could help transitions to sustainable landscapes: lessons from the Unlocking Forest Finance project. Ecosyst. Serv. 37, 100917 (2019).

Luo, X. et al. The biophysical impacts of deforestation on precipitation: results from the CMIP6 model intercomparison. J. Clim. 35, 3293–3311 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon causes substantial reductions in dry season precipitation. AGU Adv. 6, e2025AV001670 (2025).

Yoon, A. & Hohenegger, C. Muted Amazon rainfall response to deforestation in a global storm-resolving model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL110503 (2025).

Qin, Y., Wang, D., Ziegler, A. D., Fu, B. & Zeng, Z. Impact of Amazonian deforestation on precipitation reverses between seasons. Nature 639, 102–108 (2025).

Feng, Y. et al. Doubling of annual forest carbon loss over the tropics during the early twenty-first century. Nat. Sustain. 5, 444–451 (2022).

Maeda, E. E. et al. Land use still matters after deforestation. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–4 (2023).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. The Land Use Model Intercomparison Project (LUMIP) contribution to CMIP6: rationale and experimental design. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2973–2998 (2016).

Marengo, J. A. On the hydrological cycle of the Amazon Basin: a historical review and current state-of-the-art. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 3, 1–19 (2006).

Acknowledgements

UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship grant ref: MR/X034097/1 (J.B.). UK-Brazil Research and Innovation Partnership Fund through the Met Office Climate Science for Service Partnership (CSSP) Brazil as part of the Newton Fund (J.B., C.S., D.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: J.B., H.F., D.S. Methodology: J.B., C.S., D.S. Investigation: J.B., C.S., D.S. Funding acquisition: J.B., D.S. Writing—original draft: J.B., D.S. Writing—review and editing: J.B., J.V., H.F., C.S., D.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Ruben Molina and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, J.C.A., Smith, C., Veiga, J.A.P. et al. Quantifying tropical forest rainfall generation. Commun Earth Environ 7, 150 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03159-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03159-3