Abstract

Background

Preterm birth remains a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. It is classified as spontaneous, characterized by the unexpected onset of labor, or medically indicated, resulting from obstetric intervention due to pregnancy complications. The mechanisms underlying each subtype are incompletely understood, and obesity further modulates preterm birth risk through unclear biological pathways. This study aims to identify second trimester maternal plasma proteomic signatures distinguishing spontaneous and medically-indicated preterm birth and to determine how body mass index modifies these profiles.

Methods

In 100 pregnant individuals (30 spontaneous preterm birth, 30 medically-indicated preterm birth, 40 uncomplicated term deliveries), second trimester plasma was profiled using 7 K SomaScan v4.1 aptamer-based proteomic assay. Multivariate modeling and pathway analyses identified protein signatures distinguishing preterm birth subtypes, and computational network modeling with in silico perturbation analysis defined protein intermediates linking body mass index and preterm birth subtypes.

Results

Here we show distinct proteomic signatures among spontaneous preterm birth, medically-indicated preterm birth, and term deliveries. Supervised modeling achieves clear separation and identifies key discriminatory proteins including SIGLEC6, DHFR, UBASH3A, and PHB2. Early pregnancy body mass index substantially contributes to proteomic variance and modifies preterm birth associated expression of inflammatory (PROK2, IL36A), vascular (F11R) and oxidative stress (GLX1) proteins. Network perturbation identifies FABP4, CRP, UBE2G2, and LRP8 as critical intermediates linking body mass index and preterm birth.

Conclusions

Distinct proteomic profiles characterize spontaneous and medically-indicated preterm birth. Body mass index emerges as a key modifier of these molecular signatures, offering insight into the obesity-associated pathways underlying preterm birth.

Plain Language Summary

Preterm birth is a leading cause of illness and death for newborns. It can happen spontaneously or because of medical complications, such as preeclampsia. Obesity increases the risk of preterm birth, but it is not yet clear why this happens. Here we analyze blood from pregnant women in the second trimester of pregnancy to look at thousands of proteins that might differ between those who delivered early and those who delivered at full term. We discover distinct protein patterns for preterm birth types and find that body mass index strongly influences these patterns. These findings may help identify women at higher risk earlier in pregnancy and guide more personalized care and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, remains a pressing global health challenge with an estimated 13.4 million infants born preterm in 20201,2. In the United States (US), PTB remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among non-anomalous infants3, with rates persistently hovering around 10% over the past decade1,2. The societal and economic burden of PTB-associated short- and long-term complications, including neurodevelopmental impairment and development of chronic health conditions1,2,3, underscores the urgent need for improved strategies to predict and prevent PTB.

Clinically, PTB is a heterogenous syndrome with multiple etiologies. While the majority of PTB is spontaneous (sPTB) without an identifiable cause, often following idiopathic preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes, medically-indicated PTB (mPTB) rates are rising, largely driven by maternal comorbidities (e.g., obesity) and obstetrical conditions (e.g., preeclampsia [PE])4. Despite clinically distinct phenotypes, these outcomes are often grouped together, impeding the identification of specific biomarkers essential for accurate prediction and risk assessment. Recognizing sPTB and mPTB originate from unique molecular events underscores the need for specialized risk stratification tools separately addressing the burden of each.

Traditional sPTB risk assessments rely on prior PTB history, cervical length screening, or clinical variables—tools with suboptimal predictive value and limited applicability, mostly benefiting symptomatic or high-risk women5. Likewise, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends early pregnancy risk evaluation for PE rely on clinical and sociodemographic factors subject to unclear definitions (e.g., socioeconomic status) or inherent bias (e.g., Black race)6. Consequently, these guidelines broadly categorize most women “at risk,” lacking precision in identifying truly high-risk individuals. Alternative approaches, including ultrasound and maternal serum assessment7, provide improved predictive capabilities but are burdensome, resource-intensive, and primarily target limited populations. Additionally, biomarker use–such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) to placental growth factor ratio–is currently recommended for symptomatic women presenting with clinical suspicion of PE8, thus limiting its applicability for asymptomatic early detection and risk stratification.

Recognizing the limitations of current screening tools, numerous candidate biomarkers for PTB have been proposed, yet few demonstrate adequate accuracy or clinical utility. Given the multifactorial and dynamic nature of PTB, proteomics offers a systems-level approach to uncovering the biological cascades preceding early delivery. Although maternal circulating proteins have been associated with sPTB and PE9,10,11,12, current protein biomarkers, while noninvasive, lack the precision and generalizability needed for widespread clinical application.

To address these limitations, we use an untargeted, aptamer-based proteomics assay to profile the second-trimester plasma proteome of 100 women who experienced sPTB (N = 30), mPTB (N = 30, secondary to PE), or term deliveries (N = 40) without any obstetric or medical comorbidities (our Control (Ctrl) cohort). Supervised multivariate modeling achieves clear separation between PTB subtypes and term controls, identifying key discriminatory proteins including SIGLEC6 and SWAP70 in mPTB and ERRB4 and UBASH3A in sPTB. Pathway analysis reveals shared suppression of interleukin signaling across both PTB subtypes, whereas mPTB uniquely demonstrates enrichment of MAPK signaling, MHC class I antigen processing, and proteasomal degradation, consistent with immune activation and vascular stress. Additionally, we find that early pregnancy body mass index (BMI) contributes substantially to global variance in the plasma proteome. Clinically, maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) is strongly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes13. Given the complex interactions influencing BMI and PTB, we apply graphical network modeling in a Markov random field (MRF) framework14 and identify BMI-specific alterations in inflammatory (PROK2) and vascular (F11R) pathways for mPTB, and oxidative stress-related (GPX1, KL) mechanisms for sPTB. We identify direct BMI-protein-PTB dependencies, including LEP, LEPR, IRF5, and HEY1, and pinpoint specific proteins (e.g., FABP4, CRP, LRP8) whose network removal disrupts the BMI-PTB correlation, implicating lipid metabolism and immune activation as key biological pathways linking maternal obesity and PTB.

Methods

Cohort and study sample

Data were analyzed from three prospectively enrolled observational cohorts. All study procedures complied with ethical guidelines and regulatory requirements, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pennsylvania and Mount Sinai Hospital (IRB# 833333, 23-00167, 842850, 22-01728) prior to the initiation of each study.

For all included cohorts, participants with a known major anomaly, fetal aneuploidy, those who required chronic immunosuppressive treatment >30 days, had Type I Diabetes Mellitus, or human immunodeficiency virus infection were not eligible for inclusion. Participants completed 3 study visits, and blood samples were drawn into EDTA and serum separator tubes at pre-defined time points, including an overlapping time point for all cohorts in the second trimester of pregnancy (<26 weeks’ gestation). All peripheral blood biospecimens were frozen and stored at –80 °C for future use.

PRIME was a prospectively enrolled observational cohort study including nulliparous individuals who planned to deliver at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital between 12/2019 and 7/2022. IMPROVE is a prospectively enrolled observational cohort prior spontaneous PTB who planned to deliver at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania between 12/2019 and 7/2022. Eligible participants were <26 weeks’ gestation with a confirmed singleton gestation on ultrasound. MOMENTUM was a prospectively enrolled observational cohort study including Black pregnant individuals who planned to deliver at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital or Mount Sinai Hospital between 10/2020 and 6/2024. Eligible participants were <16 weeks’ gestation with a confirmed singleton gestation on ultrasound and self-identified as Black with planned delivery at one of the included institutions.

For assignment of cases and controls, see Supplementary Note 3.

Clinical data

Sociodemographic characteristics, which included maternal age, insurance, marital status, medical history, and medical conditions, obstetric history including parity and prior birth outcomes, early pregnancy BMI, and pregnancy outcomes such as gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, PTB, and neonatal birth weight, were abstracted from the electronic medical record by two trained study members. Gestational age (GA) at biospecimen collection was also recorded. Data use agreements were attained for collaboration between sites. De-identified data were stored in a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database and managed by the study team at Mount Sinai Hospital.

SomaScan

The SomaScan platform is a highly multiplexed, sensitive, quantitative, and reproducible proteomic technology that utilizes SOMAmers (Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamers)—chemically modified, highly specific DNA aptamers that bind with high affinity and specificity to pre-selected target proteins15. The 7 K SomaScan Assay v4.1 (SomaLogic Inc., Boulder, CO, USA) consists of 7596 SOMAmers, out of which 7288 target human proteins using 55 μL of plasma15. Upon binding, the aptamer-protein complexes hybridize with complementary probes immobilized on a microarray. The extent of hybridization generates a fluorescence signal, measured in relative fluorescence units (RFUs), which provides a measure of the relative abundance of each protein within the sample. For downstream analyses, RFU values of each protein were log2-transformed.

Of the 7596 SOMAmers, 6926 passed the SomaScan’s quality control and were included in further analyses. All the pre-processing and normalization were performed by Somalogic Inc. These steps consisted of first performing an adaptive normalization by maximum likelihood (ANML) and a calibration step. Samples from both cohorts were randomly allocated to different SomaScan plates to minimize batch effects between cohorts. Analyses and figures for this manuscript were made using R statistical software (v4.3.2). Samples that were above the threshold of detection were used for downstream analysis.

Unsupervised and supervised multivariate analysis

Prior to dimensional reduction, log2-transformed protein abundance levels were mean-centered and scaled by standard deviation. For unsupervised dimensional reduction analysis, we performed principal component (PC) analysis (PCA) using the built-in function “prcomp” in the R language environment. We used linear modeling to assess the relationship between the top 10 PC scores and maternal demographic variables, which include maternal age (years), GA at blood draw (weeks), PTB status, fetal sex, GA <35 weeks, and BMI (kg/m2). In these models, the response variable was the PC score, and the explanatory variables were the maternal demographics. For categorial variables consisting of two groups (fetal sex, BMI, delivery before 35 weeks), we assessed significance using a Mann–Whitney U-test. For those with three groups (PTB status), significance was assessed by Kruskal–Wallis. For those with numerical variables (i.e., maternal age, GA at blood draw), significance was assessed using Pearson’s Correlation.

For supervised dimensional reduction, we used partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLSDA). Prior to PLSDA, feature regularization was done using the Elastic net algorithm16, with the alpha parameter tuned using the “train” function from the caret package17. Elastic net regularization was performed 100 times, and for the both the 2-class mPTB vs Ctrl PLSDA model and the 3-class mPTB vs sPTB vs Ctrl PLSDA model, features that appeared in 75% of the iterations were kept. For the sPTB vs Ctrl PLSDA model, features that appeared in 60% of iterations were kept. PLSDA modeling was performed using the ‘opls’ function from the ropls package18.

Functional pathway analysis

Prior to functional pathway analysis, the protein aptamers were mapped to the UniProt Database19. This was done using the read_adat function from the SomaDataIO package in R20. For aptamers that targeted the same protein complex, the aptamer of the complex that had the highest F-statistic (ratio of the sample variance/blank buffer variance) was used. For over-representation pathway analysis, we used priori gene sets from the Reactome databases21, and to indicate significance, we used a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.25. The background list for the enrichment analysis consisted of all the proteins used in the study. Proteins used in the over-representation analysis were those that were significantly correlated with the loadings of the PLSDA model ( | rho | >0.25). Pathway analysis was done using the clusterProfiler package in R22.

Linear mixed modeling to assess BMI-PTB interaction

Pairwise comparisons between the PTB and Control groups, as well as BMI <30 and ≥30 kg/m2 groups, were done using the limma package23. Proteins were considered as significant if they had a magnitude Fold Change (FC) >1.5 (|log2FC | > 0.58) and FDR < 0.25. For the likelihood ratio test (LRT) analysis (which was done twice, one comparing mPTB vs Ctrl, and another for sPTB vs Ctrl) to examine the interaction between PTB and BMI, two linear models were constructed:

In these equations, i represents the protein of interest, PTB status represents either: (1) mPTB or Ctrl, or (2) sPTB vs Ctrl. Next, the LRT was performed to test the significance of the interaction variable (BMI*PTB_status) in the full model, which was done by evaluating the model performance of the Full Model over the Reduced Model:

where MLE = Maximum Likelihood Estimation.

Markov field modeling coupled with graphical lasso

Prior to network modeling, we first preselected 149 aptamers from the total pool of 6926 based on their biological relevance to BMI and PTB. Each aptamer targets a unique protein of interest. This reduced subset was chosen to ensure convergence of our MRF models24. Specifically, these proteins were chosen because they: (1) distinguished PTB from term controls across the latent variable (LV) 1 of the 3-class PLSDA model (Fig. 2a), (2) showed significant association with BMI (Fig. 4a), or (3) exhibited significant interaction effects between BMI and PTB subtype from LRT analysis (Fig. 4c, d).

For each network, the log2-transformed protein expression values were first scaled and centered. We then applied Graphical Lasso, using the glasso function in R25, on random subsamples of the dataset to perform stability selection26. Specifically, a range of regularization parameters (λ = 0.05–0.015 in increments of 0.01) was tested. For each λ, Graphical Lasso was run 100 times on bootstrapped samples comprising of 80% of the dataset, and for each run, we recorded whether each edge in the resulting inverse covariance matrix was non-zero (using a threshold of 1 × 10−4). These results were aggregated across all 100 subsamples to calculate an edge stability frequency. The edge matrix of the partial correlation networks (PCN) was constructed by identifying edges that exceeded a stability threshold of 90% across the range of λ values. Using this PCN edge matrix, we then estimated the maximum-likelihood estimate (MLE) Gaussian on the entire dataset27, inverted the resulting sparse inverse covariance matrix, and set all partial correlate values less than 1 × 10−4 to 0. The resulting matrix was used to define the PCN for downstream analysis.

Predicting protein perturbation impact on BMI-PTB association

To assess how individual proteins influence the association between BMI and PTB subtype, we performed an in silico knockout analysis using the precision matrix from the PCN. For each protein, we removed its corresponding node, reconstructed the correlation matrix by inverting the reduced precision matrix, and extracted the resulting BMI-PTB correlation. The change from the original correlation quantified the impact the respective protein had on the BMI-PTB association.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analysis was performed using R Statistical Software (v4.2.3), with all analyses executed using random fixed seeds to assure reproducibility. Sample sizes correspond to the total number of participants or proteins included in each analysis, as described in the figure legends and Results. While traditional experimental replicates are not applicable, reproducibility was supported through cross-validation, permutation testing, and independent null model comparisons.

To evaluate the PLSDA models, we performed 10 rounds of five-fold cross-validation (CV), with the average CV score across all rounds being reported. Within each fold of the CV steps, Elastic net feature regularization was performed. To assess model robustness, two negative control PLSDA models were constructed: (1) permuting the PTB status across all groups and repeating Elastic Net Regularization, and (2) randomly selecting the same number of proteins that were selected from Elastic Net, excluding the actual selected features. For both types of null models, we repeated a five-fold CV and compared the CV scores of the true-label PLSDA models to the null distributions. This allowed us to calculate the empirical p-values for each model.

To assure the results of the LRT are robust, a permutation test was done by shuffling the BMI values and repeating the Test Statistic calculations for each of the two comparisons. This was repeated 10,000 times and allowed us to get an empirical null distribution of Test Statistics. The p-value for the two-sided permutation test was determined by comparing the Test Statistic from the actual values to the permuted distribution. We further corrected the p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (FDR <0.25).

To assess the statistical significance of our protein perturbation results, we generated an empirical null distribution by repeating this procedure on permuted networks in which protein labels were shuffled, but BMI and PTB nodes were fixed. For each permutation (a total of 10,000 times were done), we reconstructed the network via stability selection and graphical lasso as discussed above, then repeated the knockout analysis. The resulting null distribution of correlation changes was used to calculate the FDR thresholds, allowing us to identify proteins whose perturbation had a significant influence on the BMI-PTB relationship.

Results

Study population characteristics

The pregnancy characteristics of the 100 participants included in our analytic data set are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Participants were separated by delivery outcome: 30 who experienced sPTB, 30 who experienced mPTB secondary to PE, referred to as mPTB throughout, and 40 controls (Ctrl) who ultimately delivered at term without obstetrics or medical comorbidities. There was no difference between the PTB groups and the Ctrl group in race, ethnicity, cohort type, early pregnancy BMI (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), insurance type, marital status, age at consent, GA at blood draw (weeks), or fetal sex. Those who experienced sPTB and mPTB delivered at an earlier median GA (32.5 [6.74] and 33.2 [2.95], respectively) compared to the Ctrl group (39.4 [0.73], p <0.001). To be expected, those who experienced sPTB and mPTB delivered neonates of lower median birth weight (2060 grams [1220] and 1550 grams [708], respectively) compared to those who delivered at term (3360 grams [470], p < 0.001). Participants with sPTB were more likely to have a history of sPTB (p = 0.02), and those with mPTB were more likely to have chronic hypertension (p < 0.01) compared to the term group.

Global proteomic variation and principal component analysis

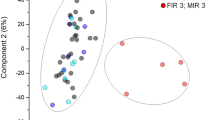

Using 7 K SomaScan Assay v4.1, we profiled the second trimester (16−24 weeks’ gestation) maternal proteome in participants who experienced sPTB, mPTB, and Ctrl. While N = 100 sample size is typical for deeply phenotyped obstetric cohorts, it is modest for high-dimensional proteomics. Thus, all multivariate findings are presented as hypothesis-generating and supported by conservative statistical procedures. Unsupervised PCA did not show clear clustering of samples by outcome (sPTB, mPTB, or Ctrl) in the top PC (Fig. 1b). However, maternal factors such as early pregnancy maternal BMI contributed substantially to variance in the plasma proteome. For example, PC2 correlated with maternal age at delivery and GA at sampling (p <0.05; Supplementary Fig. 1b), and PC5 was associated with GA at blood draw (p <0.01; Supplementary Fig. 1c). Notably, PC6 was associated with maternal BMI and PTB status (Fig. 1c). PC6 values were significantly different between BMI categories (p < 0.05) and between outcome groups (p <0.05), indicating that obesity contributes to a portion of the proteome (Fig. 1c). These findings suggest that while baseline maternal features (e.g., obesity) imprint on the second trimester plasma proteome, PTB outcomes induce more subtle global shifts not captured by the first few PC. Nevertheless, the association of PC6 with both obesity and PTB subtype hints at a latent proteomic axis that differentiates preterm cases from uncomplicated pregnancies delivered at term.

a Study experimental study design. A line corresponds to a single patient, and each dot corresponds to the Gestational Age (GA) as to when the was sample collected. The GA of when the mothers delivered is indicated by the triangle b Heatmap shows the -log10(p-value) of the linear regression each of the Top 10 PCs against the following maternal covariates: Maternal Age (years), GA at blood draw (weeks), PTB status (mPTB or sPTB or Ctrl), sex of the fetus (male or female), whether mothers delivered before 35 weeks GA, and body mass index (BMI) (<30 or ≥30 kg/m2 c Violin plot relating PC6 against BMI (<30 or ≥30 kg/m2) (left) and PTB status (Control, sPTB, and mPTB) (right). The middle blank line represents the median, whereas the other lines represent the first and third quartiles. Significance was determined by a Kruskal–Wallis followed by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple hypothesis correction. If statistically significant, a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was performed (< 30 vs > = 30 BMI p-value = 0.0004; Control vs mPTB p-adj = 0.0103). *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

Multivariate modeling distinguishes PTB subtypes

We performed direct pairwise comparison between the Ctrl, mPTB, and sPTB groups to identify biomarkers distinguishing each PTB subtype. While the mPTB vs Ctrl comparison (Supplementary Fig. 2a) revealed two differentially expressed proteins, INHBA | INHA and SIGLEC 6 (FDR < 0.15 and FC >1.5), no differentially expressed proteins were found in the sPTB vs Ctrl or the mPTB vs sPTB comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c).

Due to the limited number of differentially expressed proteins in pairwise comparisons, we performed supervised multivariate modeling, specifically PLSDA with Elastic Net-selected features. The resulting three-class model achieved clear separation among the three groups in the LV space: LV1 captured variation distinguishing both mPTB and sPTB from Ctrl (Fig. 2b, left), while LV2 captured differences between mPTB and sPTB (Fig. 2b, right). Our model achieved modest separation under cross-validation (Fig. 2c). We evaluated the robustness with two negative control models (permuted labels and random feature selection), run under identical cross-validation/feature selection, and computed empirical p-values by comparing the observed cross–validation scores to the corresponding null distributions. Thus, interpretation focuses on stable, regularly selected features.

a PLSDA model was build using Elastic Net-selected features measured from 100 samples (Control (gray, N = 40), mPTB (red, N = 30), and sPTB (blue, N = 30)). The dot plot (top) shows each sample represented by a dot, and the ellipse represents a 95% confidence interval for each of the different PTB groups. (bottom) Bar pot representing the Variable Importance of Projection (VIP) results, which indicate the most important proteins used to construct the PLSDA model. The color of each protein indicates which cohort it is most enriched in, based on the median value. b Bar plots show the loadings of the Elastic-net selected features on the (left) latent variable 1 (LV1), and the (right) latent variable 2 (LV2), with the color of each bar showing which PTB group the respective protein is enriched in (c) Accuracies from 10 repetition of 5-fold cross validation (CV) of PLSDA coupled with Elastic Net feature regularization. Each point represents one repetition (N = 10 independent CV repetitions), and the distribution reflects accuracy scores across 100 permutation trials per repetition. Model vs random features p-value = 0.001, model vs permuted labels p-value = 0.005. d Representative univariate plots of Elastic-net selected proteins used to construct PLSDA model. Significance was determined by a Kruskal–Wallis followed by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple hypotheses correction. If statistically significant, a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was performed. KLK8 - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0247; Ctrl vs sPTB padj = 0.0383. PRMT - Ctrl vs sPTB padj = 0.0128. IRF5 - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0012; Ctrl vs sPTB = 0.0023. EEF2K - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0393; Ctrl vs sPTB padj = 0.0011; UBASHA3A - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0006; SIGLEC6 - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0006; mPTB vs sPTB padj = 0.0213. SWAP70 - Ctrl vs mPTB padj = 0.0293; mPTB vs sPTB padj = 0.0087. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

Importantly, the multivariate model identified specific protein features with high variable importance in projection (VIP) scores (VIP > 1), including SIGLEC6, DHFR, UBASH3A, and PHB2 (Fig. 2a bottom). Each of these emerged as a key discriminator across LV, indicating their strong association with PTB outcomes. LV1 loadings revealed higher levels of proteins like KLK8 and PRMT3 in Ctrls, while IRF5 and EEF2K were higher in PTB groups. Across LV2 loadings, ERBB4 and UBASH3A were elevated in sPTB, while SIGLEC6 and SWAP70 were elevated in mPTB. Representative univariate comparisons (Fig. 2d) confirmed that top proteins also differed individually between groups (p <0.05 for each). This multivariate analysis defines a composite second-trimester plasma protein signature distinguishing pregnancies destined for sPTB and mPTB from term deliveries (Fig. 2a, b).

Mechanistic differences and pathway enrichment in PTB subtypes vs. Controls

To further interrogate the mechanistic differences underlying sPTB and mPTB, we constructed two separate PLSDA models comparing each PTB subtype to term controls (Fig. 3a, b). Each model was built using Elastic net-selected features and revealed distinct LV structures, with minimal overlap in discriminating proteins (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). In the mPTB vs Ctrl comparison (Fig. 3a, left), discriminatory proteins included INHBA | INHA, SIGLEC6, and LRRC25 (Supplementary Fig. 3a), whereas in the sPTB vs Ctrl model (Fig. 3b, left), separation was driven by KLK11, PHB2, and EEF2K (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Model performances were strong, as assessed by statistical tests (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

b (left) PLSDA models were build using Elastic Net-selected features from 70 measured in (a). Control (gray, N = 40) vs mPTB (red, N = 30), and b Control (gray, N = 40) vs sPTB (blue, N = 30). The dot plot (top) shows each sample represented by a dot, and the ellipse represents a 95% confidence interval for each of the different PTB groups. (bottom) Bar pot representing the Variable Importance of Projection (VIP) results, which indicate the most important proteins used to construct the PLSDA model. The color of each protein indicates which cohort it is most enriched in, based on the median value. (right) Heatmaps showing the top 30 proteins with the highest Pearson Correlation value when compared against the LV1 of each respective PLSDA model. c Reactome processes associated with proteins most correlated ( | rho | >0.25) with the LV1 of the respective PLSDA model (red = mPTB vs Ctrl, blue = sPTB vs Ctrl). Pathways that were enriched relative to Ctrl were those most associated with proteins that had rho > 0.25 with the LV1 of the respective PLSDA model. Pathways that were Suppressed relative to Ctrl were those most associated with proteins that had rho < −0.25 with the LV1 of the respective PLSDA model. Pathways displayed have an FDR < 0.25 (Benjamini–Hochberg Procedure). d Heatmaps of the log2FC (mPTB or sPTB vs Control) of proteins associated with the displayed pathway.

To interpret the biological relevance of the PLSDA model, we correlated the LV1 scores from each with the full set of measured proteins and visualized the top 30 with the highest Pearson correlation to LV1 (Fig. 3a, b, right panel). While PLSDA models used a smaller set of Elastic Net-selected features, the correlation heatmaps capture broader proteome-wide patterns, including proteins not used to construct the model. In mPTB, most correlated proteins were downregulated relative to Ctrl, such as BMP2, IFNL2, and KLK11. However, proteins such as IRF5 and CD79A, which are involved in innate and adaptive immune responses28,29, were upregulated. In sPTB, most of the top correlated proteins, such as NLGN1, ACAN, and FGFBP3, were negatively associated with LV1, indicating suppression of these in sPTB vs Ctrl. We observed a small number of elevated proteins in sPTB, such as IRF5, PHB2, and EEF2K, which are involved in cellular stress responses and inflammatory regulation30. Despite subtype-specific protein signatures, notable within-group heterogeneity was observed, with some proteins exhibiting marked upregulation and others downregulation, underscoring the complex and varied molecular landscape in each PTB subtype.

We next leveraged the LV1 from each model to perform correlation-based Reactome pathway enrichment analysis (Fig. 3c). Proteins with a positive correlation with LV1 (rho > 0.25) were used to find enriched pathways and those with a negative correlation (rho < −0.25) were used to identify suppressed pathways, and the log2FC heatmaps provide detail of pathway-associated proteins (Fig. 3d). Specific to mPTB, IGF transport and uptake pathway was suppressed. Additionally, mPTB showed pathway enrichment in MAPK signaling, MHC class I antigen processing, and proteasomal degradation, consistent with immune activation, vascular stress, and inflammation typical of PE31,32. While both PTB subtypes showed suppression of Interleukin Signaling, including components such as VIM, ANXA1, IL10, and MMP2, IL18 was notably upregulated in mPTB but not sPTB, suggesting divergent pro-inflammatory signaling within this pathway. While some suppressed pathways are shared across PTB subtypes, such as cytokine signaling, interleukin cascades, and extracellular matrix organization, distinct proteins further delineate the unique profile associated with mPTB. A full list of the pathways is shown in Supplementary Data 1.

Influence of maternal BMI on PTB-associated proteomic changes

Given the known influence of maternal obesity on inflammation and PE risk, as well as the impact of obesity on global proteomic variance (Fig. 1b), we examined how maternal early-pregnancy BMI modifies the protein changes associated with PTB outcomes. We first compared protein profiles between non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) participants within each group (Fig. 4a). Obesity had a significant effect on the proteome in all groups. A total of 284 proteins were significantly altered by BMI in the Ctrl group alone (FDR <0.25, |log2FC | >0.58). In contrast, the mPTB group showed four BMI-associated protein differences (Fig. 4a, middle), while the sPTB group showed 48 significant proteins (Fig. 4a, right). A Venn diagram of differentially expressed proteins comparing obese vs non-obese groups (Fig. 4b), which reveals that obesity’s impact on the maternal plasma proteome is largely context-specific, with a single protein shared across all groups and just one shared between the mPTB and sPTB subtypes and Ctrl cohort.

a Volcano Plots displaying differential expressed proteins (DEP) between <30 vs ≥30 BMI groups in Control (left, N = 16 for <30, N = 24 for ≥30), mPTB (middle, N = 10 for <30, N = 20 for ≥30), and sPTB (right, N = 14 for <30, N = 16 for ≥30). Proteins that are identified as differentially expressed (FDR < 0.25 and a |FC | >0.58) are highlighted in gray (Control), red (mPTB), or blue (sPTB). b Venn Diagram comparing the DEP that are distinct and shared between each comparison shown in (a). c, d Results of Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) examining the interaction between BMI and PTB. c The red dots indicate proteins that are significant in the LRT of the mPTB vs Control comparison (FDR <0.15 and p-value < 0.05). Significance was determined by permutation testing. d The blue dots indicate the proteins that are significant in the LRT of the sPTB vs Control comparison (FDR < 015 and p-value < 0.05). The names of a select set of the most differentially expressed proteins with the lowest FDR values are also displayed. For both c, d univariate plots are shown of proteins that are significant in LRT. CLYBL (<30 BMI) p-value = 0.0003. SULT1B1 (≥30 BMI) p-value = 0.00005. KRTAP2-4 (<30 BMI) p-value = 0.0023. PROK2 (≥30 BMI) p-value = 0.00005. MMAB (≥30 BMI) p-value = 0.0358. MZFI (<30 BMI) p-value = 0.0388; (≥30 BMI) p-value = 0.0062. KL (<30) p-value = 0.0010. GSTM4 (<30 BMI) p-value = 0.0158. GPX1 (<30 BMI) p-value = 0.0025. DECR2 (≥30 BMI) p-value = 0.0314. Significance was determined by a two-sided Wilcoxon-rank-sum test (*p <0.05, **p <0.01).

To formally test for BMI-PTB interaction effects on protein expression, we performed LRT for each protein (Fig. 4c, d). Permutation-based significance testing identified 196 and 301 proteins as significantly interacting with BMI in the context of mPTB and sPTB, respectively (FDR <0.25). Several proteins showed diverging expression patterns between obese and non-obese mPTB cases relative to Ctrl (Fig. 4c). PROK2, a chemokine-like molecule associated with inflammation and angiogenesis33, was elevated specifically in those with obesity who experienced mPTB. Similarly, F11R, a tight junction protein associated with vascular integrity34 was downregulated in the obese group who experienced mPTB, suggesting obesity-specific mechanisms underlying mPTB.

A distinct set of proteins exhibited BMI-dependent associations with sPTB (Fig. 4d). GPX1, an enzyme known to protect against oxidative stress35, appears to be dysregulated in cases of sPTB in both obese and non-obese women. While reduced expression impairs the clearance of free radicals, excessive expression may also be detrimental by depleting essential reactive oxygen species35, underscoring its complex role in sPTB pathophysiology. Additionally, KL, an endocrine regulator of metabolism and aging36, was significantly elevated in obese sPTB cases (p <0.05), suggesting a unique obesity-specific mechanism contributing to sPTB risk.

Partial correlation networks reveal BMI-protein-PTB dependencies

To further understand how maternal early-pregnancy BMI influences protein expression and PTB outcomes, we applied MRF, specifically PCN, to our dataset to identify the direct associations between BMI, a subset of selected proteins of interest, and PTB subtype (mPTB and sPTB). In our networks, the nodes represent the variables (proteins, BMI, and PTB status), and the edges represent the direct dependencies, the partial correlates, which were estimated using the graphical lasso algorithm25,37,38(Fig. 5a). We generated two separate PCN, one fit using only mPTB and Ctrl samples, and another of sPTB and Ctrl. We chose to work with 149 proteins to assure convergence of our MRF networks24. Proteins were chosen because they: (1) distinguished PTB from term controls across the LV1 of the 3-class PLSDA model (Fig. 2a), (2) showed significant association with BMI (Fig. 4a), or (3) exhibited significant interaction effects between BMI and PTB subtype from LRT analysis (Fig. 4c, d) (Supplementary Data 2). Considering all correlations with a magnitude > 0.15, the networks are highly connected, containing 7830 edges for the mPTB network and 7713 for the sPTB network (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Filtering for only partial correlation edges yielded 1758 edges in the mPTB network and 1682 in the sPTB network (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 4b, c), retaining only ~5% of the original edges, thus highlighting the presence of spurious and indirect correlations present in our original network structure. To evaluate whether these partial correlations sufficiently capture the structure of the full network, we compared the observed indirect correlations to those estimated from the direct edges alone. We were accurately able to estimate these correlations (R2 of 0.969 for mPTB and 0.966 for sPTB), confirming the retained direct edges encode nearly all relevant dependencies in the system (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

a Schematic illustrating how correlations (specifically indirect) arise from direct (aka partial) correlations, emphasizing how graphical lasso can remove indirect correlations (b, c). Network representations of b correlations and c partial correlations (magnitude > 0.15) among 149 pre-selected proteins, BMI, and PTB status. Networks are shown separately for the mPTB vs control cohort (top, N = 70, NControl = 40 and NmPTB = 30) and sPTB vs control cohort (bottom, N = 70, NControl = 40 and NsPTB = 30). Nodes represent variables (protein, BMI, and PTB status), and node colors indicate selection criteria: blue for proteins correlated with the LV1 of the 3-way PLSDA model (Fig. 2a), red for those associated with BMI (Fig. 4a), purple (for sPTB), and green (for mPTB) for proteins significant in BMI-PTB interaction from LRT analysis. d Heatmaps depicting the correlations and partial correlations to BMI and PTB status. Proteins chosen to highlight are those that are a partial correlate to either BMI and PTB. e Univariate linear regression plots of proteins that are partial correlates to both BMI and PTB status. The color of each line represents the color of the cohort (sPTB: blue, mPTB: red, and Control: gray). The partial correlation (p.corr) values between the protein and BMI, and the protein and PTB, are annotated on the plot.

We next examined and compared the full correlation network (determined by Pearson’s correlation) to the partial correlations between the proteins, BMI, and PTB status, separated by PTB subtype (Fig. 5d). Initial full correlation analyses revealed 80 proteins showing a strong correlation with BMI, and 61 with PTB status in the mPTB network (magnitude > 0.15) (Fig. 5b, top and Fig. 5d). In the sPTB network, 96 proteins were strongly associated with BMI and 60 with PTB (Fig. 5b, bottom and Fig. 5d). After eliminating the spurious correlations, only 5 proteins in the mPTB network and 8 in the sPTB network retained a strong correlation with BMI, while 11 and 4 proteins, respectively, retained strong associations with PTB status. In both PTB networks, we identified 11 proteins that were direct partial correlates to BMI and 11 proteins that were partial correlates to PTB status (Fig. 5d, left), suggesting a set of conserved network features shared across PTB subtypes.

Several proteins exhibited direct correlations to BMI only in one of the two networks. In the mPTB network, MIA, ARL11, and FOLR1 were direct edges to BMI, suggesting unique metabolic, apoptotic, and inflammatory response-associated mechanisms39,40,41 specific to the link between BMI and mPTB. In the sPTB network, CXCL13 and STAMBPL1 had direct edges to BMI, which may reflect adaptive immune- and stress-specific signaling dysregulation42,43 unique to the association between BMI and sPTB. Some proteins were directly correlated to BMI in both networks, including LEP, exhibiting a strong positive partial correlation, and LEPR, showing a negative partial correlation with BMI (Fig. 5d).

Subtype-specific edges were also observed with respect to PTB status. Direct edges in the mPTB network to PTB status included ACTN4, HOMER2, and TFB2M. In contrast, MIEF1 was directly linked to the sPTB network, suggesting subtype-specific mitochondrial involvement44. Some proteins, such as NR3C2, RTN4RL1, and IRF5, were linked to PTB status in both networks and likely represent common denominators in regulating stress and immune response in both PTB subtypes. While HEY1, a transcription factor activated downstream of the Notch signaling pathway45, and FCRL4, an immunoglobin receptor modulating memory B-cell function46, were partial correlates with PTB status in both networks, a reversal in directionality was observed, both exhibiting positive partial correlate in mPTB network but negative partial correlate in the sPTB network.

To further characterize proteins with dual relevance, we focused on those with direct edges to both BMI and PTB in each network (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5). Univariate plots with their partial correlate values listed on the plot of six of these proteins are shown in Fig. 5e; a summary of biological insights is given in Supplementary Note 1. Our findings highlight the value of PCN analysis in unraveling direct molecular associations from those that are indirect or confounded by intermediary factors.

Perturbation analysis identifies key proteins mediating the BMI-PTB relationship

To identify proteins that are critical in establishing a relationship between BMI and PTB status, we conducted a perturbation analysis using the PCNs. This approach utilizes the conditional dependencies determined in the PCN structure to assess how the perturbation of an individual protein affects the estimated correlation between BMI and PTB status. We compared the unperturbed estimated correlation between BMI and PTB, which was derived from the estimated covariance matrix of the PCN refit from the sparse inverse covariance matrix to the “perturbed” correlation computed after removing one protein at a time from the network. The perturbed correlation reflects the conditional distribution of BMI and PTB given the remaining network structure, allowing us to calculate the influence of each protein on the BMI-PTB relationship.

Perturbation analysis for mPTB vs Ctrl (top) and sPTB vs Ctrl (bottom) networks is shown in Fig. 6a. Proteins whose removal resulted in a significant shift in correlations relative to empirical thresholds (FDR <0.15), determined from the null distribution of permuted data (Supplementary Fig. 6), were considered critical intermediates of the BMI-PTB link. Critical intermediators unique to the mPTB network, whose removal resulted in a decrease in correlation between PTB status and BMI, included IL36A, CD2, IGSF3, FABP4, ATP5BP, and EEF2K. Interestingly, CD2, a T-cell surface marker associated with immune activation and adhesion47, IGSF3, a protein involved in epithelial signaling and adhesion48, and FABP4, a protein involved in lipid metabolism and adipose tissue inflammation37, were direct edges to BMI in the mPTB network (Fig. 5d), as well as a significant protein in the differential protein expression comparing BMI groups (<30 and ≥30 kg/m2) independent of PTB status (Fig. 4a left, Supplementary Data 2). In contrast, critical intermediators exclusive to the sPTB network included ENOX2, GMEMB2, and CRP, which are involved in DNA damage response, redox regulation, stress response, and systemic inflammation49,50, and may reflect distinct stress adaptation mechanisms in sPTB. Notably, LAS2 was the only protein whose perturbation increased the correlation between BMI and PTB in the sPTB network, suggesting a potential suppressive role. As previously seen in Fig. 5e, LAS2 was negatively correlated with BMI and positively associated with PTB, and has been linked to reduced infiltration of CD4 + T cells and macrophages51. Its higher expression may mitigate immune activation, potentially offering protection against obesity-driven inflammation that contributes to sPTB risk. Importantly, shared protein intermediates linking BMI-PTB in both PTB networks were identified (Fig. 6b), including UBE2G2, TMEM132A, SCG3, LRP8, and APLP1. These are associated with integrin signaling, lipid metabolism, vascular signaling, and cell differentiation and migration, suggesting endoplasmic-reticulum (ER)-stress, lipid transport dysfunction, and disturbances of cell signaling cascades52,53,54,55 are pathways implicated in obesity-related PTB.

a Barplots showing the difference in the estimated correlation between BMI and PTB status (left for mPTB vs Control (N = 70, NControl = 40 and NmPTB = 30), right for sPTB vs Control (N = 70, NControl = 40 and NsPTB = 30) before and after the perturbation of a protein from the network. The estimated ‘perturbed’ BMI-PTB correlation is computed from the conditional distribution of the MRF after the exclusion of a protein, one at a time. Only proteins whose removal results in a significant difference between the unperturbed versus perturbed BMI-PTB correlation (FDR <0.15) compared to a permuted null distribution (total of 10,000 permutations) are shown. Red dashed line indicates the thresholds used to signify significance. b Venn Diagram showing distinct and overlapping critical proteins (FDR <0.15) between the perturbation analysis of the mPTB vs Ctrl network and the sPTB vs Ctrl Network.

An example of a subnetwork analysis using Dijkstra’s algorithm56 to find the shortest path in the MRFs linking BMI, UBE2G2/TMEM132A, and PTB is discussed in Supplementary Note 2 (with associated Supplementary Fig. 7). Together, this analysis identifies a subset of proteins whose topological influence within the MRF network significantly contributes to the inferred relationship between BMI and PTB. These proteins may represent potential mechanistic intermediates or biomarkers linking early pregnancy BMI and PTB risk. Together, these multi-scale analyses - from differential expression and multivariate modeling to network and perturbation inference - reveal that maternal BMI shapes distinct proteomic networks underlying sPTB and mPTB, identifying key molecular intermediate linking inflammatory, vascular, and oxidative stress pathways to PTB (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Discussion

In this study, we utilized an untargeted aptamer-based proteomic approach to comprehensively profile maternal plasma in the second trimester, identifying distinct molecular signatures preceding sPTB and mPTB compared to uncomplicated pregnancies delivered at term. Our primary findings demonstrate that, despite some common proteins involved in innate immunity and cell signaling underlying both PTB subtypes, significant divergence exists in proteins and pathways related to MAPK signaling and antigen presentation. Multivariate modeling identified unique proteomic patterns predictive of each PTB subtype. Notably, early pregnancy BMI substantially influenced proteomic variation, highlighting the complex interplay between immune and metabolic pathways modulating PTB risk.

We found INHBA|INHA, implicated in placental dysfunction and impaired trophoblast invasion31, and SIGLEC6, a leptin binding receptor in placental tissue that modulates inflammatory response57, were elevated in those destined for mPTB. Our detection of elevated SIGLEC6 in the periphery suggests its potential utility as a biomarker of placental pathology associated with the development of PE. Enrichment in Class I MHC-mediated antigen processing pathways was seen in mPTB, driven specifically by proteins such as B2M, TPP2, and FGG, which align with hallmark features of PE: elevated B2M is linked to heightened immune activation and oxidative stress32, dysregulation of TPP2 contributes to aberrant inflammation and altered trophoblast function58, and increased FGG reflects vascular inflammation and endothelial injury59. Although interleukin signaling pathways were overall downregulated in both PTB subtypes, IL-18, produced by inflammasomes, was notably upregulated in mPTB, consistent with prior work demonstrating elevated IL-18 in placentas and serum of women with PE60. This dual pattern of upregulated and downregulated pathways with difference in individual protein expression reflects broad systemic dysfunction in mPTB.

Conversely, pathway analysis did not identify any pathways associated with proteins upregulated in sPTB relative to the term control, suggesting sPTB is associated with a dampening of key regulatory programs, possibly impairing maternal-fetal immune adaptation or tissue remodeling necessary for pregnancy maintenance. Further, the lack of a univariate proteomic signature in sPTB underscores the intrinsic heterogeneity within this clinical outcome, suggesting that robust molecular signatures might be localized to the uteroplacental interface and not fully detectable in peripheral plasma.

Uniquely, our study examines maternal obesity, prompted by PCA findings showing early pregnancy BMI as a key driver of proteomic variation. Obesity independently contributes to chronic systemic inflammation61, which likely alters the circulating proteome. Indeed, maternal obesity is a growing problem in the US with approximately one-third of women classified as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) at the start of pregnancy62. Notably, pre-pregnancy and pregnancy obesity are significant clinical factors associated with PE risk13. Data surrounding obesity and sPTB risk is mixed and often confounded by maternal comorbidities; some indicate obesity is associated with a modest increase in sPTB risk with the greatest effects seen at earlier GA63, while others have found no significant association or only associations accompanied by other risk factors64.

Our data-driven exploration reveals distinct obesity-specific alterations influencing PTB risk. Notably, PROK2, a chemokine associated with angiogenesis, inflammation, and obesity33,65, was elevated specifically among obese mPTB cases, suggesting a role in obesity-related inflammation and placental dysfunction characteristic of PE. Conversely, KL, a previously undescribed marker in PTB research, was distinctly elevated in obese women experiencing sPTB. Known for its regulatory roles in aging, metabolism, and inflammation36, elevated KL levels may represent a compensatory response attempting to mitigate obesity-related inflammation and oxidative injury, factors frequently implicated in spontaneous preterm birth pathogenesis. The identified proteins (e.g., PROK2 in mPTB; KL in sPTB) may serve as biomarker candidates for risk stratification in the context of obesity or provide clues to therapeutic targets to mitigate PTB risk in pregnancies complicated by obesity.

The use of PCN and perturbation analyses uncovered shared and PTB subtype-specific molecular intermediates linking BMI to PTB outcomes, while filtering out spurious and confounding associations that would otherwise obscure mechanistic insight. For example, LRRC25 demonstrated BMI-dependent suppression and positive correlation with mPTB, potentially exacerbating NF-κB-mediated inflammation66, which may underlie the heightened immune response observed specifically within the obese mPTB group. We observed opposing partial correlations of LEP and LEPR with BMI—LEP positively and LEPR negatively correlated—consistent with features of leptin resistance. This resistance, characterized by elevated circulating leptin levels failing to induce appropriate biological responses due to diminished LEPR activity or signaling67, underscores the potential impact of obesity-induced metabolic imbalances on PTB risk. Additionally, rare autosomal-recessive mutations causing LEPR deficiency have been clinically linked to severe obesity and metabolic disturbances68, further supporting the concept that disrupted leptin signaling may contribute to obesity-related PTB risk.

We see the functional contributions to PTB risk differ significantly, contingent on the underlying biological and clinical context. In the mPTB network, ACTN4, a key regulator of trophoblast proliferation and differentiation during early pregnancy, disruption of which is well documented in the pathogenesis of PE69, was associated with PTB status. In the sPTB network, MIEF1 was associated with PTB status, and is known to play a critical role in mitochondrial dynamics of the female reproductive tract70, supporting tissue adaptation to help maintain cellular homeostasis, disruption of which may impair responses to mechanical and environmental stress71. Given the link between altered tissue and extracellular matrix mechanics and sPTB72, dysregulated MIEF1 signaling may contribute to sPTB pathogenesis. Although certain proteins are commonly implicated across both PTB subtypes, we see the contrasting partial correlations of HEY1 and FCRL445,46, highlighting subtype-specific roles: positive correlation with mPTB suggesting PE-associated inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, while negative correlation with sPTB may reflect a protective or compensatory role in modulating immune responses in the context of infection or stress-triggered preterm labor.

These findings dovetail with emerging ideas of subtyping obstetric syndromes by molecular profiles. For example, two distinct molecular subtypes of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy have been demonstrated: one characterized by placental gene dysregulation and another by maternal immune system activation73. Our proteomic networks substantiate the need for this molecular bifurcation, positioning obesity as a pivotal factor modulating immune responses and angiogenic pathways that potentially predispose individuals to distinct PTB subtypes.

Our study offers several important strengths, notably the unbiased, high-throughput measurement of the maternal plasma proteome using an aptamer-based proteomic assay capable of simultaneously quantifying thousands of proteins15. This approach enables the discovery of novel biomarker candidates without a priori hypotheses, in contrast to traditional targeted assays. By distinguishing sPTB from mPTB, our approach identifies unique proteomic signatures associated with each subtype and how these signatures are influenced by BMI. Additional methodological strengths include the prospective design across multiple cohorts and stringent participant matching by race, BMI, and cohort type, which reduces confounding but lacks generalizability.

Notwithstanding, our study is limited by moderate sample sizes, particularly within subgroup analyses, potentially constraining the detection of subtle proteomic variations. The absence of significant univariate differences between sPTB and control groups likely reflects the biological and clinical heterogeneity of sPTB, and the limited sensitivity of plasma-based assays to capture localized immune or metabolic processes. While our sample size precluded granular BMI stratification, our findings underscore the influence of early pregnancy obesity, meriting validation in larger, more diverse, BMI-stratified cohorts in order to enhance generalizability. Mechanistic studies are also required to determine whether the proteins identified play a causal role in precipitating PTB or are downstream reporters of upstream events. It is worth noting that some markers might be consequences rather than causes of pathological processes. Distinguishing this will require longitudinal sampling and experimental models to test the consequences of modulating proteins on clinical disease.

Although there are several benefits to utilizing MRF analysis, there are a few caveats. Specifically, the MRF framework relies on the assumption of Gaussianity and linear dependency between variables. Future applications of this tool could incorporate non-Gaussian or discrete graphical models, such as Ising models74, which are better suited for handling binary variables like PTB status. Additionally, temporal MRFs or dynamic Bayesian networks75 could be used to capture the evolving influence of maternal BMI on proteomic networks across gestation. These extensions would further refine our understanding of how maternal risk factors perturb pregnancy-specific biology in both a time-depending and subtype-specific manner.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal assessment of proteomic alterations across gestation, aiming to identify the earliest GA timepoints at which meaningful biomarker deviations occur, thereby enhancing specificity and predictive accuracy. Validation of identified proteomic biomarkers, such as SIGLEC6, SWAP70, IRF5, and KL in independent cohorts is critical to establishing their clinical utility and predictive robustness for routine prenatal assessment. Because we only assessed peripheral plasma, we could not characterize the local milieu of the endometrium, decidua, or placenta. Future work interrogating the maternal-fetal interface is warranted to further elucidate the mechanistic drivers of the observed systemic proteome. Furthermore, molecular intermediates highlighted by network analyses, such as LEP, LEPR, and LAS2, illustrate mechanistic connections between maternal obesity and PTB risk, presenting promising targets for future therapeutic interventions. Indeed, proteins implicated in obesity-related inflammation, notably PROK2 and LEPR, represent particularly compelling candidates for novel preventative strategies in high-risk populations.

Our untargeted aptamer-based plasma proteomic analysis delineates distinct molecular pathways during the second trimester that differentiate pregnancies destined for sPTB and mPTB from those resulting in uncomplicated term deliveries. Importantly, we demonstrate the significant yet underexplored impact of maternal obesity on these proteomic alterations. Although changes in individual proteins were modest, multivariate models capturing combinational effects provided substantial predictive power, aligning with the prevailing understanding that complex obstetric syndromes require composite biomarker panels. This comprehensive proteomic characterization not only reinforces the need for nuanced, subtype-specific predictive models but also establishes foundational knowledge critical for biomarker discovery and targeted therapeutic interventions, ultimately enhancing maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Data availability

The proteomics data are deposited in the Immunology Database and Analysis Portal (Immport) Shared Data under accession number SDY3306; available upon application to the site. Source data are provided in the following Supplementary Data Files: Fig. 1b, c (Supplementary Data 3), Fig. 2 (Supplementary Data 4), Fig. 3 (Supplementary Data 5), Fig. 4a, c, d (Supplementary Data 6), Fig. 5d, e (Supplementary Data 7), and Fig. 6a (Supplementary Data 8). To ensure the confidentiality of our participants, the individual-level data will not be made publicly available. All other data presented in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code and scripts to reproduce results are available through the public GIT repository (https://github.com/plopez842/PTB_BMI_protein_study), with the following https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1788097076.

References

Ohuma, E. O. et al. National, regional, and global estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 402, 1261–1271 (2023).

Martin, J. A. & Osterman, M. J. K. Shifts in the distribution of births by gestational age: United States, 2014-2022. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 73, 1–11 (2024).

Gregory E. C. W., Valenzuela C. P. & Hoyert, D. L. Fetal Mortality: United States, 2022. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep.https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/158788 (2024).

Goldenberg, R. L., Culhane, J. F., Iams, J. D. & Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371, 75–84 (2008).

Meertens, L. J. E. et al. Prediction models for the risk of spontaneous preterm birth based on maternal characteristics: a systematic review and independent external validation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 97, 907–920 (2018).

Force USPST, Davidson, K. W. et al. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 326, 1186–1191 (2021).

Rolnik, D. L. et al. ASPRE trial: performance of screening for preterm pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 50, 492–495 (2017).

Zeisler, H. et al. Predictive value of the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in women with suspected preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 13–22 (2016).

Beernink, R. H. J., Schuitemaker, J. H. N., Zwertbroek, E. F., Scherjon, S. A. & Cremers, T. Early pregnancy biomarker discovery study for spontaneous preterm birth. Placenta 139, 112–119 (2023).

de Almeida L. G. N. et al. Proteomics and metabolomics profiling of platelets and plasma mediators of thrombo-inflammation in gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Cells. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11081256 (2022).

Tarca, A. L. et al. Crowdsourcing assessment of maternal blood multi-omics for predicting gestational age and preterm birth. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100323 (2021).

Markenson, G. R. et al. Performance of a proteomic preterm delivery predictor in a large independent prospective cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2, 100140 (2020).

D’Souza, R., Horyn, I., Pavalagantharajah, S., Zaffar, N. & Jacob, C. E. Maternal body mass index and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 1, 100041 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Markov field network model of multi-modal data predicts effects of immune system perturbations on intravenous BCG vaccination in macaques. Cell Syst. 15, 1278–1294 e4 (2024).

Gold, L., Walker, J. J., Wilcox, S. K. & Williams, S. Advances in human proteomics at high scale with the SOMAscan proteomics platform. N. Biotechnol. 29, 543–549 (2012).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 67, 301–320 (2005).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Thevenot, E. A., Roux, A., Xu, Y., Ezan, E. & Junot, C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index, and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J. Proteome Res. 14, 3322–3335 (2015).

UniProt C. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D204–D212 (2015).

Field S. SC, Standard BioTools, Inc. Input/Output ‘SomaScan’ Data. https://somalogic.github.io/SomaDataIO/, https://somalogic.com

Jassal, B. et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D498–D503 (2020).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2, 100141 (2021).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Mazumder, R. & Hastie, T. The graphical lasso: new insights and alternatives. Electron J. Stat. 6, 2125–2149 (2012).

Friedman J. H. T. & Tibshirani R. Graphical Lasso: Estimation of Gaussian Graphical Models. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glasso/index.html.

Meinshausen, N. & Bühlmann, P. Stability selection. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 72, 417–473 (2010).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. Undirected graphical models. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction Springer Series in Statistics. 625–648 (2009).

Krausgruber, T. et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1-TH17 responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 231–238 (2011).

Tkachenko, A., Kupcova, K. & Havranek, O. B-cell receptor signaling and beyond: the role of igalpha (CD79a)/Igbeta (CD79b) in normal and malignant B cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010010 (2023).

Leprivier, G. et al. The eEF2 kinase confers resistance to nutrient deprivation by blocking translation elongation. Cell 153, 1064–1079 (2013).

Wang, Y., Li, B. & Zhao, Y. Inflammation in preeclampsia: genetic biomarkers, mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 13, 883404 (2022).

Sarween, N. et al. Humoral immunity in late-onset Pre-eclampsia and linkage with angiogenic and inflammatory markers. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 80, e13041 (2018).

Negri, L. & Ferrara, N. The prokineticins: neuromodulators and mediators of inflammation and myeloid cell-dependent angiogenesis. Physiol. Rev. 98, 1055–1082 (2018).

Babinska, A. et al. F11-receptor (F11R/JAM) mediates platelet adhesion to endothelial cells: role in inflammatory thrombosis. Thromb. Haemost. 88, 843–850 (2002).

Handy, D. E. & Loscalzo, J. The role of glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 188, 146–161 (2022).

Xu, Y. & Sun, Z. Molecular basis of Klotho: from gene to function in aging. Endocr. Rev. 36, 174–193 (2015).

Goudswaard, L. J. et al. Effects of adiposity on the human plasma proteome: observational and Mendelian randomisation estimates. Int J. Obes. 45, 2221–2229 (2021).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics 9, 432–441 (2008).

Arya, S. B., Kumar, G., Kaur, H., Kaur, A. & Tuli, A. ARL11 regulates lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage activation by promoting mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 9892–9909 (2018).

Platko, K., Lebeau, P. & Austin, R. C. MAPping the kinase landscape of macrophage activation. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 9910–9911 (2018).

Nawaz, F. Z. & Kipreos, E. T. Emerging roles for folate receptor FOLR1 in signaling and cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 159–174 (2022).

Kowarik, M. C. et al. CXCL13 is the major determinant for B cell recruitment to the CSF during neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 93 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. E3 ligase RNF167 and deubiquitinase STAMBPL1 modulate mTOR and cancer progression. Mol. Cell 82, 770–784 e9 (2022).

Otera, H., Miyata, N., Kuge, O. & Mihara, K. Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission via MiD49/51 is essential for apoptotic cristae remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 212, 531–544 (2016).

Fischer, A., Schumacher, N., Maier, M., Sendtner, M. & Gessler, M. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev. 18, 901–911 (2004).

Jourdan, M. et al. Characterization of human FCRL4-positive B cells. PLoS ONE 12, e0179793 (2017).

Selvaraj, P. et al. The T lymphocyte glycoprotein CD2 binds the cell surface ligand LFA-3. Nature 326, 400–403 (1987).

Barclay, A. N. Membrane proteins with immunoglobulin-like domains—a master superfamily of interaction molecules. Semin. Immunol. 15, 215–223 (2003).

Jurga, M., Abugable, A. A., Goldman, A. S. H. & El-Khamisy, S. F. USP11 controls R-loops by regulating senataxin proteostasis. Nat. Commun. 12, 5156 (2021).

Morre, D. J. & Morre, D. M. Cell surface NADH oxidases (ECTO-NOX proteins) with roles in cancer, cellular time-keeping, growth, aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radic. Res. 37, 795–808 (2003).

Ma, Y. et al. C18ORF54 promotes immune infiltration and poor prognosis as a potential biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 15, 5007–5034 (2023).

Li, B. & Niswander, L. A. TMEM132A, a novel Wnt signaling pathway regulator through wntless (WLS) interaction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 599890 (2020).

Ju, T., Bocik, W., Majumdar, A. & Tolman, J. R. Solution structure and dynamics of human ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ube2g2. Proteins 78, 1291–1301 (2010).

Yang, T. & Williams, B. O. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins in skeletal development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 97, 1211–1228 (2017).

Muller, U. C. & Zheng, H. Physiological functions of APP family proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006288 (2012).

Thorup, M. Undirected single-source shortest paths with positive integer weights in linear time. J. ACM 46, 362–394 (1999).

Rumer, K. K., Uyenishi, J., Hoffman, M. C., Fisher, B. M. & Winn, V. D. Siglec-6 expression is increased in placentas from pregnancies complicated by preterm preeclampsia. Reprod. Sci. 20, 646–653 (2013).

Preta, G., de Klark, R., Gavioli, R. & Glas, R. The enigma of tripeptidyl-peptidase II: dual roles in housekeeping and stress. J. Oncol. 2010 https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/128478 (2010).

Zhu, Y. et al. Changes and significance of plasma fibrinogen gamma-chain concentration in preeclampsia patients. J. Clin. Lab Anal. 35, e23704 (2021).

Huang, X., Huang, H., Dong, M., Yao, Q. & Wang, H. Serum and placental interleukin-18 are elevated in preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 77–87 (2005).

Gregor, M. F. & Hotamisligil, G. S. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev. Immunol. 29, 415–445 (2011).

Driscoll, A. K. & Gregory, E. C. W. Increases in pre-pregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 392,1–8 (2020).

Cornish, R. P. et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and risk of preterm birth: a collaboration using large routine health datasets. BMC Med. 22, 10 (2024).

McDonald, S. D., Han, Z., Mulla, S., Beyene, J. & Knowledge Synthesis, G. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 341, c3428 (2010).

Nebigil, C. G. Prokineticin is a new linker between obesity and cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 4, 20 (2017).

Feng, Y. et al. LRRC25 functions as an inhibitor of NF-kappaB signaling pathway by promoting p65/RelA for autophagic degradation. Sci. Rep. 7, 13448 (2017).

Myers, M. G., Cowley, M. A. & Munzberg, H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annu Rev. Physiol. 70, 537–556 (2008).

Kleinendorst, L. et al. Leptin receptor deficiency: a systematic literature review and prevalence estimation based on population genetics. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 182, 47–56 (2020).

Peng, W., Liu, Y., Qi, H. & Li, Q. Alpha-actinin-4 is essential for maintaining normal trophoblast proliferation and differentiation during early pregnancy. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 19, 48 (2021).

Zou, W., Ji, D., Zhang, Z., Yang, L. & Cao, Y. Players in mitochondrial dynamics and female reproduction. Front Mol. Biosci. 8, 717328 (2021).

Romani, P. et al. Mitochondrial mechanotransduction through MIEF1 coordinates the nuclear response to forces. Nat. Cell Biol. 26, 2046–2060 (2024).

Amabebe, E., Ogidi, H. & Anumba, D. O. Matrix metalloproteinase-induced cervical extracellular matrix remodelling in pregnancy and cervical cancer. Reprod. Fertil. 3, R177–R191 (2022).

Elovitz, M. A. et al. Molecular subtyping of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 16, 2948 (2025).

Cheng, J., Levina, E., Wang, P. & Zhu, J. A sparse Ising model with covariates. Biometrics 70, 943–953 (2014).

Descombes, X., Kruggel, F. & von Cramon, D. Y. Spatio-temporal fMRI analysis using Markov random fields. IEEE T Med. Imaging 17, 1028–1039 (1998).

Lopez, P. Custom code for protein networks are influenced by maternal bmi and differentiate preterm birth types: initial release (v1.0.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17880970 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants in this study, along with the help of Fatoumata Barry in recruitment for these cohorts. We acknowledge funding from NIH/NIAID 1U19AI167899-01 (to A.G.E., D.A.L., M.A.E.) and MGH ECOR Patricia and Scott Eston MGH Research Scholars Award (to A.G.E.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and supervised study: M.A.E. and D.A.L; Obtained samples: V.R. and L.N.; Analyzed data: P.A.L.Z. and C.A.D.; Aided computational modeling: L.K.; Interpreted results: P.A.L.Z., C.A.D., A.G.E., M.A.E., and D.A.L.; Wrote manuscript: P.A.L.Z., C.A.D., M.A.E., and D.A.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.G.E. serves as a consultant for Mirvie, Inc, YourBioHealth, and Merck Pharmaceuticals; and has received research funding from Merck Pharmaceuticals. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopez Zapana, P.A., DeBolt, C.A., Karginov, L. et al. Protein networks are influenced by maternal BMI and differentiate preterm birth types. Commun Med 6, 111 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01376-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01376-1