Abstract

Background

Frailty is an important factor in human aging associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes. Frailty metrics are time intensive to collect making them difficult for larger scale application.

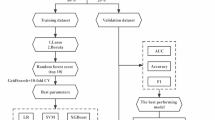

Methods

We apply machine learning to predict these frailty metrics, associated risk factors, and adverse outcomes from activity data. We use activity data collected using Actigraphy wearable accelerometer sensors, which are devices that measure acceleration along three axes of movement. Models were evaluated using Area Under the receiver operator Curve (AUC), Area Under Precision Recall Curve (AUPRC), Spearman rank test, Mann-Whitney U test, or Kruskal-Wallis test on repeated subsampling of train and test sets. All statistical tests are reported using -log10(P-value).

Results

Machine learning models show strong predictive performance even with small amounts of accelerometry data available. They are also able to better determine adverse outcomes such as hospitalization and mortality than frailty metrics themselves in our geriatric population.

Conclusions

This approach of wearable activity data-based prediction of frailty offers a surrogate (proxy or estimate) for determining frailty metrics in a scalable manner. It can also be used to determine adverse outcomes such as hospitalizations and mortality, allowing frailty to be used as a metric in other studies or medical practices.

Plain language summary

Frailty occurs during human aging and is associated with a broad range of unfavourable outcomes. Frailty is measured using various scores but these often rely on subjective information, are labor intensive to measure, and are not assessed over time. This work presents objective measures indicative of frailty, based on wearable sensors that measure movement. This was tested in a group of people with an average age of 75. Application of a computational model using this data enabled long-term outcomes, including hospitalization and death, to be more accurately predicted than using existing frailty measures. This work demonstrates that 48 hours of data collection per patient is sufficient. This type of system could be used on a larger number of people, enabling those at risk of unfavourable outcomes to be targeted with medical interventions or support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Requests for original data can be handled through (www.ciberfes.es/) via a review committee. The hospital reviews and determines the purposes for the data requests and what data can be released. Data requests can be sent to: Research and teaching unit, Virgen del Valle Hospital Ctra. Cobisa S/N, 45071 Toledo – Spain, info@estudiotoledo.com. All procedures were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Toledo Hospital and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for human studies.

Supplemental data can be accessed either as the included.csv files or as.rda files available at the github repository in the results folder https://github.com/tripodlaboratories/actigraphy-frailty/tree/main/results52. The included supplementary data files 1, 2, 4 and 8 contain results (rho, p-values, and RMSE) for each individual model repeat of FTS components, risk factors & outcomes, FTS5 components, and the various frailty metrics respectively. Supplementary Data 3, 5, 6 and 7 contain the average model repeat prediction evaluations for risk factors & outcomes, FTS5 components, FTS components, and the various frailty metrics respectively. Actigraphy activity data and descriptions of clinical outcomes, risks, and frailty components are provided as.csv’s in the data folder of the associated github https://github.com/tripodlaboratories/actigraphy-frailty/tree/main/data52.

Code availability

Code necessary to reproduce results, figures, and models can be found at https://github.com/tripodlaboratories/actigraphy-frailty52. This code was run using R 4.1.2 and xgboost 1.5.2.1 on a macOS 12.3.1 system. There are no restrictions on its access or use.

References

Department of Economics and Social Affairs, U. N. World Population Ageing 2019. (2020).

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381, 752–762 (2013).

Fried, L. P. et al. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat. Aging 1, 36–46 (2021).

Campbell, A. J. & Buchner, D. M. Unstable disability and the fluctuations of frailty. Age Ageing 26, 315–318 (1997).

Rodriguez-Mañas, L. & Fried, L. P. Frailty in the clinical scenario. Lancet 385, e7–e9 (2015).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M156 (2001).

Rockwood, K. et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173, 489–495 (2005).

Li, G. et al. Comparison between frailty index of deficit accumulation and phenotypic model to predict risk of falls: data from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW) Hamilton cohort. PLoS ONE 10, e0120144 (2015).

Woo, J., Leung, J. & Morley, J. E. Comparison of frailty indicators based on clinical phenotype and the multiple deficit approach in predicting mortality and physical limitation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 60, 1478–1486 (2012).

García-García, F. J. et al. A new operational definition of frailty: the Frailty Trait Scale. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 15, 371.e7–371.e13 (2014).

García-García, F. J. et al. Frailty trait scale-short form: a frailty instrument for clinical practice. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 1260–1266.e2 (2020).

Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. The frailty syndrome in the public health agenda. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 68, 703–704 (2014).

Landi, F. et al. Moving against frailty: does physical activity matter?. Biogerontology 11, 537–545 (2010).

Peterson, M. J. et al. Physical activity as a preventative factor for frailty: the health, aging, and body composition study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 64, 61–68 (2009).

van Hees, V. T. et al. A Novel, Open Access Method to Assess Sleep Duration Using a Wrist-Worn Accelerometer. PLoS ONE 10, e0142533 (2015).

Santos-Lozano, A. et al. Actigraph GT3X: validation and determination of physical activity intensity cut points. Int. J. Sports Med. 34, 975–982 (2013).

Dinh-Le, C., Chuang, R., Chokshi, S. & Mann, D. Wearable health technology and electronic health record integration: scoping review and future directions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e12861 (2019).

Schwenk, M. et al. Wearable sensor-based in-home assessment of gait, balance, and physical activity for discrimination of frailty status: baseline results of the Arizona frailty cohort study. Gerontology 61, 258–267 (2015).

Razjouyan, J. et al. Wearable sensors and the assessment of frailty among vulnerable older adults: an observational cohort study. Sensors 18, (2018).

Kim, B., McKay, S. M. & Lee, J. Consumer-grade wearable device for predicting frailty in Canadian home care service clients: prospective observational proof-of-concept study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e19732 (2020).

Sayed, N. et al. An inflammatory aging clock (iAge) based on deep learning tracks multimorbidity, immunosenescence, frailty and cardiovascular aging. Nat. Aging 1, 598–615 (2021).

Rahman, S. A. & Adjeroh, D. A. Deep learning using convolutional LSTM estimates biological age from physical activity. Sci. Rep. 9, 11425 (2019).

Rockwood, K., McMillan, M., Mitnitski, A. & Howlett, S. E. A frailty index based on common laboratory tests in comparison with a clinical frailty index for older adults in long-term care facilities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 842–847 (2015).

Garcia-Garcia, F. J. et al. The prevalence of frailty syndrome in an older population from Spain. The Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 852–856 (2011).

Mañas, A. et al. Dose-response association between physical activity and sedentary time categories on ageing biomarkers. BMC Geriatr 19, 270 (2019).

Freedson, P. S., Melanson, E. & Sirard, J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 30, 777–781 (1998).

Chinoy, E. D. et al. Performance of seven consumer sleep-tracking devices compared with polysomnography. Sleep 44, (2021).

Sivertsen, B. et al. A comparison of actigraphy and polysomnography in older adults treated for chronic primary insomnia. Sleep 29, 1353–1358 (2006).

Radtke, T., Rodriguez, M., Braun, J. & Dressel, H. Criterion validity of the ActiGraph and activPAL in classifying posture and motion in office-based workers: A cross-sectional laboratory study. PLoS ONE 16, e0252659 (2021).

An, H.-S., Kim, Y. & Lee, J.-M. Accuracy of inclinometer functions of the activPAL and ActiGraph GT3X + : A focus on physical activity. Gait Posture 51, 174–180 (2017).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining - KDD ’16 785–794 (ACM Press, https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785.(2016).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Statist. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Additive logistic regression: a statistical view of boosting (With discussion and a rejoinder by the authors). Ann. Statist. 28, 337–407 (2000).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning. vol. 103 (Springer New York, (2013).

King, R. D., Orhobor, O. I. & Taylor, C. C. Cross-validation is safe to use. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 276–276 (2021).

Maaten, L. van der & Hinton, G. Visualizing Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research (2008).

Kraus, W. E. et al. Relationship between baseline physical activity assessed by pedometer count and new-onset diabetes in the NAVIGATOR trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 6, e000523 (2018).

Bandeen-Roche, K. et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 262–266 (2006).

Gill, T. M., Gahbauer, E. A., Allore, H. G. & Han, L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 418–423 (2006).

Graham, J. E. et al. Frailty and 10-year mortality in community-living Mexican American older adults. Gerontology 55, 644–651 (2009).

Ensrud, K. E. et al. A comparison of frailty indexes for the prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and mortality in older men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 492–498 (2009).

Burnham, J. P., Lu, C., Yaeger, L. H., Bailey, T. C. & Kollef, M. H. Using wearable technology to predict health outcomes: a literature review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 25, 1221–1227 (2018).

Walsh, J. T., Charlesworth, A., Andrews, R., Hawkins, M. & Cowley, A. J. Relation of daily activity levels in patients with chronic heart failure to long-term prognosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 79, 1364–1369 (1997).

Yates, T. et al. Association between change in daily ambulatory activity and cardiovascular events in people with impaired glucose tolerance (NAVIGATOR trial): a cohort analysis. Lancet 383, 1059–1066 (2014).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Cunningham, H., Ewart, A., Riggs, L., Huben, R. & Sharkey, L. Sparse Autoencoders Find Highly Interpretable Features in Language Models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2309.08600.(2023)

Howlett, S. E., Rutenberg, A. D. & Rockwood, K. The degree of frailty as a translational measure of health in aging. Nat. Aging 1, 651–665 (2021).

Fallahzadeh, R. et al. Objective Activity Parameters Track Patient-specific Physical Recovery Trajectories After Surgery and Link With Individual Preoperative Immune States. Ann. Surg. 277, e503–e512 (2023).

Ghaemi, M. S. et al. Multiomics modeling of the immunome, transcriptome, microbiome, proteome and metabolome adaptations during human pregnancy. Bioinformatics 35, 95–103 (2019).

Zalocusky, K. A. et al. The 10,000 immunomes project: building a resource for human immunology. Cell Rep 25, 513–522.e3 (2018).

Furman, D., Davis, M. M., Dekker, C. L., Tibshirani, R. & Maecker, H. 1000 Immunomes Project. https://med.stanford.edu/1000immunomes.html.

tripodlaboratories/actigraphy-frailty: Initial Release. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18187284.(2026)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the NIH R35GM138353 (to N.A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.—Conceptualisation, Methodology, Analysis Design, Analysis, Writing, Visualization, Data Curation. A.M.—Conceptualisation, methodology, Data Acquisition, Writing. K.S., F.J.G.-G., J.L.-R., L.M.A., and L.R.-M.—Writing, Data Interpretation. A.L.C., C.E., D.D.F., T.P., M.B., M.X., N.G.R., R.F., B.G., and M.A.—Review and Editing, Analysis Design. I.A., and N.A.—Conceptualisation, Review and Editing, Supervising, Project Administrating

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Björn Friedrich and Emanuele Seminerio for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Culos, A., Manas, A., Shidara, K. et al. A machine learning model for frailty based on wearable device measurements. Commun Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01419-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-026-01419-7