Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases involve the progressive loss of neurons in the brain and nervous system, leading to functional decline. Early detection is critical for improving outcomes and advancing therapies. Optical biosensors, some of which offer rapid, label-free, and ultra-sensitive detection, have been applied to early diagnosis and drug screening. This review examines the principles and performance of different optical biosensors used for diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases and discusses potential future advancements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Overview of neurodegenerative disease

Neurons form the fundamental structural and functional units of the nervous system and are essential for brain function and cognition, encompassing high-level activities such as sensory processing, motor control, memory, emotional formation, learning, adaptation, and complex thinking1. These specialized cells are distributed throughout the human body and, like other cellular components, can degrade in both quality and quantity over time due to aging or external factors. Neuron degeneration can significantly impair brain function and overall health, leading to immediate effects such as localized loss of function and long-term consequences that may result in permanent disability of affected brain regions. This progressive neuronal degradation can result in a decline in neurotrophic support and chronic degeneration2,3.

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are conditions characterized by the gradual loss or dysfunction of neurons in specific regions of the brain. These diseases are marked by cognitive decline, motor impairment, behavioral and psychological changes, and a progressive loss of independence4. NDDs are predominantly observed in older adults due to the correlation between neuronal loss and aging5. Among these conditions, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are the most prevalent6. AD typically arises from the abnormal accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau proteins around brain cells, leading to brain atrophy. On the other hand, PD is associated with decreased dopamine production in the brainstem and the pathological aggregation of alpha-synuclein. Both AD and PD share underlying mechanisms such as protein misfolding, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation within the nervous system.

As of 2024, it is estimated that nearly 7 million Americans aged 65 or older are living with AD, with approximately 10% of individuals in this age group affected by the disease7. Similarly, the incidence of PD continues to rise, with more than 90,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States. If current trends persist, the number of Americans with PD is projected to reach approximately 1.2 million by 20308. Although aging is a major risk factor for NDDs, genetic mutations, such as those in the Huntington gene that lead to Huntington’s Disease, and protein misfolding, which contributes to prion diseases, have also been identified as causative factors. Notably, around 5% of AD cases occur in individuals under the age of 659, highlighting that while age is a significant factor, it is not the sole contributor to the development of these diseases.

Current state of NDD diagnostics

Due to improvements in quality of life and a growing average lifespan, the number of individuals affected by NDDs has increased significantly5. This rise, coupled with a rapid annual growth in NDD cases, presents a substantial public health challenge. Approximately 25% of the population carries the APOE e4 gene, which is associated with an elevated risk of AD10. These trends highlight the need for proactive research and early detection strategies for NDDs.

Early studies on NDDs, particularly AD and PD, demonstrated the formation of amyloid beta plaques, tau tangles, and Lewy bodies long before clinical symptoms emerged, highlighting the challenge of early detection. In the present era, neurodegenerative conditions such as AD and PD are often evaluated through imaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET)11,12, optical coherence tomography (OCT)13, computed tomography (CT)14, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)15,16, which provide valuable insight on central nervous system structure, function, and degradation. In addition to conventional imaging, miniaturized imaging systems such as portable low-field MRI (LF-MRI) have been used for AD diagnostics17, while emerging systems such as head-mounted doppler OCT show potential for NDD diagnostics18. Despite these advancements, the criteria for diagnosing NDDs in clinical settings remain complex due to symptom overlap with normal aging and the heterogeneity of disease presentation.

Biomarkers, including protein and molecular markers, are a promising avenue for early screening, risk assessment, and diagnostic accuracy19. Protein and molecular biomarkers have demonstrated potential for early diagnosis in other diseases, and recent studies have shown that microRNA biomarkers could differentiate mild cognitive impairment from age-matched controls with a sensitivity of 84–94%20. Other biomarker candidates, such as long non-coding RNA and circular RNA, are also being actively investigated21. Nevertheless, the broader clinical adoption of biomarkers faces challenges due to inconsistent correlations with clinical outcomes and a lack of standardization in measurement techniques, assay protocols, and diagnostic thresholds22.

Optical biosensors have emerged as a promising solution to these challenges, offering a sensitive and specific method for real-time, non-invasive biomarker detection23. These devices transduce biological interactions into optical signals using techniques such as fluorescence, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), interferometry, and colorimetric detection, as well as resonator-based approaches like whispering-gallery mode (WGM) sensors. In this article, we review both the biosensors themselves, as well as their underpinning bioassay technologies. Optical biosensors show significant potential for enhancing diagnostic capabilities in NDDs and other conditions, addressing some of the current limitations in early detection and monitoring.

Overview of optical biosensors and underlying techniques for NDDs

The concept of a biosensor was introduced in 1956 by Leland C. Clark who developed the oxygen electrode, and later, in 1962 created the first true biosensor for glucose detection24. In 1975, Lubbers and Opitz introduced the term optode with their development of a fiber-optic sensor for measuring carbon dioxide or oxygen24. Since then, advances in physics, especially in optics—have opened new possibilities for biosensor development24. This progress has led to innovative types of optical biosensors, including SPR, fiber-optic, interferometric, fluorescence-based, and optical resonator biosensors. In recent years, technological advancements in materials and integration have improved the sensitivity, specificity, and usability of optical biosensors. These improvements have enabled applications such as point-of-care testing and artificial intelligence-driven diagnostics25. Optical biosensors are now recognized as useful tools for disease detection and monitoring, especially for NDDs.

Colorimetric-based techniques

Colorimetric assays utilize visible color changes triggered by specific analytes, eliminating the need for complex instrumentation. For example, gold nanoparticle (AuNP) aggregation-based assays leverage the plasmonic properties of AuNPs, where their interaction with target analytes or proteins induces aggregation, resulting in color shifts proportional to analyte concentration. These properties have been explored for detecting biomarkers relevant to NDDs26.

Similarly, enzyme-linked colorimetric bioassays, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), have been used to detect NDD-related biomarkers27. These assays rely on antigen-antibody interactions, with a secondary enzyme-linked antibody and substrate facilitating a quantifiable color change proportional to the biomolecule concentration. While ELISA is not a biosensor, it serves as a foundational bioassay for many optical biosensing technologies.

Due to their simplicity and adaptability, colorimetric assays have been integrated into portable, cost-effective, and user-friendly platforms, such as paper-based biosensors. These systems, which require minimal components and straightforward analysis, hold promise for accessible and decentralized NDD diagnostics28.

Fluorescent-based biosensors

The concept of fluorescence-based biosensors varies across different types of biosensors and assays. However, they all rely on the sensitivity achieved through detecting fluorescence generated by selective interactions, such as antigen-antibody or ligand-receptor binding. One commonly used fluorescence-based bioassay that serves as the basis for some optical biosensing technologies is ELISA. In this method, a selective antibody binds to a specific antigen immobilized on a coated plate. If the detection antibody is conjugated to an enzyme, adding a suitable chemical substrate triggers a reaction that generates a fluorescent signal, which can then be measured. Alternatively, if the antibody is directly labeled with a fluorophore, fluorescence can be detected without the need for a substrate reaction (Fig. 1a). By quantifying the intensity of the fluorescent signal, researchers can determine the concentration of the target protein in the sample. ELISA is widely regarded as the gold standard and has been extensively used in research on drug efficacy and disease detection29.

a Schematic representation of ELISA, highlighting antibody-antigen interactions and fluorescent signal generation; b schematic of SIMOA, showing molecular detection using microwells and paramagnetic beads; c schematic of a CRISPR-based fluorescence biosensor, illustrating target recognition and fluorescent signal release through Cas enzyme activity; and d schematic of FRET, demonstrating energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores during close-range protein binding.

Single molecule array (SIMOA)

SIMOA30 is an advanced digital immunoassay technique that shares similarities with ELISA. Both methods rely on antibodies to capture target proteins and use fluorescence as a detection signal. However, SIMOA uses a plate with over 200,000 microwells, each capable of capturing a single paramagnetic bead. In the SIMOA assay, paramagnetic beads are coated with specific antibodies and then mixed with the target protein and an enzyme (Fig. 1b). These functionalized beads are isolated into individual microwells using oil to seal each well, ensuring that statistically only one bead is present per well. A fluorescent substrate that reacts with the enzyme is then introduced, generating a fluorescent signal within each microwell. This fluorescence is detected and analyzed to quantify the target protein. SIMOA offers significantly improved sensitivity, detecting target concentrations down to the femtomolar range. Additionally, it supports multiplexing, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple analytes in a single assay31.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)

Another biosensing tool that utilizes fluorescence is based on CRISPR. CRISPR was originally developed for editing DNA sequences in cells and has significant applications in gene therapy and disease treatment. More recently, CRISPR has been adapted for use in biosensing, where it uses fluorescence-based detection to identify and quantify target molecules. In this approach, nucleic acids labeled with fluorescent markers are added to a mixture containing the sample, CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins, and specific guide RNA (gRNA) sequences. The gRNA directs the Cas enzyme to the target DNA or RNA in the sample. Once bound, the Cas enzyme exhibits trans-cleavage activity, cutting nearby nucleic acids, including the labeled ones. This cleavage releases the fluorescent signal, which can be measured to determine the exact concentration of the target molecule in the sample (Fig. 1c). Due to the high specificity of gRNA for complementary sequences and the signal amplification capabilities of Cas enzymes, CRISPR-based biosensors achieve high sensitivity, detecting target concentrations as low as the attomolar range32. Additionally, the short assay time makes these biosensors highly suitable for point-of-care applications.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)

FRET is another technique used to measure fluorescent emission resulting from protein-binding interactions. Unlike methods that rely on a single fluorescent protein, FRET utilizes two fluorophores: a donor and an acceptor. When the donor and acceptor come into close proximity (typically within 1–10 nm), often as a result of conformational changes or binding between proteins or peptides, non-radiative energy transfer occurs from the donor to the acceptor. This energy transfer results in fluorescent emission from the acceptor (Fig. 1d). The close-range interaction between the donor and acceptor fluorophores enables FRET biosensors to achieve high sensitivity, detecting concentrations as low as the picomolar range, along with specificity for the target analyte33.

Label-free optical biosensing technologies for NDDs

SPR

SPR is a label-free spectroscopic technique used to monitor molecular interactions in real time between target analytes, such as chemicals or biological ligands, and a surface immobilized with specific receptors34. SPR works by exploiting the resonant oscillation of free electrons at the interface of a semi-transparent metal film when light interacts with it at a specific angle, causing light to propagate along a metal-dielectric interface. This coupling of free-space light into a mode guided at the metal-dielectric interface only occurs at a specific resonant incidence angle that is highly sensitive to the local refractive index at the interface. This coupling can be identified by a strong dip in light that otherwise would have been reflected. (Fig. 2a).

When a target analyte binds to receptors immobilized on the metal surface, it changes the refractive index at the interface. This refractive index change shifts the angle of resonant coupling into the surface plasmon polariton, allowing tracking of molecular binding events in real time. The total refractive index change Δnd is described by the equation:

where (dn/dv) vol is the refractive index change per unit volume of the analyte, ΔΓ is the concentration change of the target molecule at the surface, and h is the thickness of the interaction region.

This direct correlation between refractive index changes and molecular interactions enables SPR to detect binding events. SPR can measure reflective angle shifts as small as 0.1 millidegrees and detect surface-bound protein densities as low as 0.1 pg/mm²35.

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)

LSPR is a related technique to SPR that also relies on surface plasmon excitation but operates on metallic nanoparticles instead of a continuous metal film. In LSPR, the interaction of incident light with nanoparticles smaller than the wavelength of the light excites localized surface plasmons—coherent oscillations of electrons within the nanoparticles. These oscillations occur at a resonant frequency, which enhances light absorption and scattering at the nanoparticle surface, making LSPR extremely sensitive to changes in the local refractive index (Fig. 2b).

When an analyte binds to the surface of a nanoparticle, it causes a shift in the local refractive index, which alters the resonant peak frequency of the localized plasmon. By monitoring this frequency shift in real time, researchers can detect molecular binding events. LSPR has achieved detection limits as low as zeptomolar concentrations by observing color changes caused by the colloidal aggregation of gold nanoparticles during DNA hybridization36. LSPR performance, however, is sensitive to variations in the size, shape, and uniformity of plasmonic nanorods, which can lead to inconsistencies in signal reproducibility.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)

SERS is an advanced form of Raman spectroscopy that enhances the detection of molecules by amplifying their Raman scattering signals. In SERS, the LSPR of metallic nanoparticles is excited by incident light, generating a strong local electromagnetic field near the metal surface. This enhanced field amplifies the Raman scattering signal of nearby molecules, significantly increasing sensitivity, particularly at plasmonic ‘hot spots’ such as nanogaps and sharp edges (Fig. 3)37. This field enhancement increases the Raman scattering signal, making SERS more sensitive than conventional Raman spectroscopy.

Metallic nanoparticles or nanostructured surfaces enhance the Raman scattering signal of biomolecules through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). Incident light excites the plasmon resonance, generating a strong electromagnetic field near the surface, amplifying the signal from nearby molecules.

The SERS enhancement factor (EF) is calculated using the following equation38:

where ISERS and INRS are the intensities of SERS and the normal Raman signals, respectively, and Nsurf and Nvol represent the number of targeted molecules on the metallic surface and the total number of molecules in the excitation volume, respectively.

This enhancement can amplify the Raman signal by factors ranging from 104 to 10839. Such signal amplification enables SERS to achieve detection of AD proteins at concentrations as low as 138 fg/mL40.

Optical whispering gallery mode (WGM) resonator biosensors

The concept of WGMs originated from the behavior of acoustic waves in circular galleries, where sound waves travel along the perimeter with minimal energy loss. This phenomenon was later adapted to optics, where light circulates within closed-loop resonators without requiring end mirrors, resonating at specific wavelengths.

For effective optical resonance, WGM resonators require materials with low optical loss, high thermal and mechanical stability, and compatibility with biosensing applications. Common materials include glass and silicon nitride. In WGM optical resonators, the resonance at specific wavelengths is highly sensitive to particles binding to the resonator’s surface. These binding events alter the optical path length and shift the resonant wavelength. Initially attributed to thermo-optic effects, this wavelength shift is now understood to result from changes in the effective refractive index.

Light is confined within the resonator through TIR and constructive interference. When a particle binds to the surface, it perturbs the optical path length, causing a change in the effective refractive index and shifting the resonant wavelength, often toward longer wavelengths. The relationship between the resonance wavelength, λ, and the effective refractive index neff is given by:

where R is the resonator radius and m is the resonant mode number.

Various types of WGM resonators are used in biosensing, including rings, spheres, microbubbles, and microtoroids41. Among these, microspheres42, microrings43, and microtoroids44,45,46,47,48,49 are the most widely utilized (Fig. 4). Microring resonators (Fig. 4a) are particularly advantageous for on-chip integration and use in fluidic systems due to their ease of fabrication and stable waveguide coupling. However, lithography limitations often result in microrings having lower quality factors (Q-factors) and thus shorter photon confinement times compared to microspheres (Fig. 4b) and microtoroids (Fig. 4c), which impacts their sensitivity.

a Microring resonator. Microrings are compact, chip-integrated, and compatible with microfluidic systems, but have lower sensitivity than microspheres or microtoroids. b Microsphere resonator. Microspheres have ultra-high Q factors but are difficult to integrate on chip as they are not fabricated in a planar format and c Microtoroid resonators. Microtoroids have both ultra-high-Q factors and are fabricated on a chip, opening up the potential for a high-sensitivity multiplexed assay.

Despite this limitation, microring resonators have achieved sensitivity levels of 73 nm/RIU (nanometers per refractive index unit) when fabricated from silicon50 and up to 179.7 nm/RIU with silicon nitride43. In biosensing applications, microrings have demonstrated the ability to detect proteins at concentrations as low as 63.54 ng/mL51 and DNA at nanomolar levels52. Toroidal resonators, when paired with noise reduction techniques, enable single-molecule detection53,54,55,56,57,58,59 and achieve zeptomolar detection limits60 in under a minute61. Typically, light is evanescently coupled into these devices using an optical fiber, but recently it has been shown that light can be free-space coupled into these devices and sensing experiments performed62. In addition, toroidal devices can generate on-chip frequency combs in water, thus opening up the possibility for a compact identification, as well as detection platform63,64.

Optical biosensing techniques in the context of NDD detection

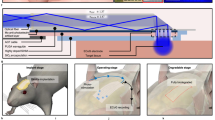

Optical biosensors have emerged as a way for detecting NDDs, offering advantages in sensitivity and non-invasive analysis. An overview of how an optical biosensor can be used for NDD diagnostics is shown in Fig. 5.

Samples may include human-derived fluids, murine models, or commercially available purified protein fragments, such as amyloid β 1-42. Optical biosensor platforms can detect, for example, target biomolecules through specific antibody binding, producing measurable optical signals. These signals are analyzed to generate response curves, providing quantitative data for biomarker detection and disease progression assessment.

AD detection

AD is characterized by the buildup of Aβ plaques and tau protein tangles in specific brain regions, leading to neuronal death and brain atrophy. Consequently, Aβ and tau proteins are key biomarkers for AD detection and are widely used across diverse biosensing platforms.

In terms of colorimetric assays, gold nanoparticle aggregation assays have been used to sense Aβ 1–40 in aqueous solution at 0.6 nM65. In addition, colorimetric paper-based ELISA assays have sensed Aβ 1–42 in human plasma and buffer at concentrations of 100 pg/mL and 63.04 pg/mL, respectively28.

ELISA has been widely utilized for detecting biomarkers in vitro66. Studies using ELISA have demonstrated differences in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of total tau (t-tau), phosphorylated tau at threonine 181 (p-tau181), and Aβ-42 between AD patients and control groups. Specifically, AD patients show elevated levels of t-tau and p-tau181 alongside reduced levels of Aβ42. Another biomarker, Visinin-like protein-1 (VILIP-1), associated with neuronal damage, also showed elevated levels in AD patients (506 ± 20 pg/mL) vs controls67. Additionally, ELISA enables detection of plasma Aβ-42 at a sensitivity of 1 pg/mL68. Although ELISA has been widely used in AD research for detecting biomarkers across various biofluids, AD researchers have raised concerns about its sensitivity and robustness, especially for detecting low-abundance targets69. These limitations have led to the exploration of more sensitive techniques, but ELISA remains a tool for biomarker quantification. A summary of detection limits for different optical biosensors used in AD diagnostics is provided in Table 1.

Recent advancements in diagnostic techniques have introduced CRISPR-based fluorescence bioassays that enhance the detection sensitivity for AD biomarkers, particularly Aβ40 and Aβ42 in CSF. Notably, a study developed a CRISPR-assisted aptasensor combining the high specificity of aptamers for Aβ biomarkers with CRISPR/Cas12a-based fluorescent detection. This approach achieved a limit of detection (LOD) of 1 pg/mL for Aβ40 and 0.1 pg/mL for Aβ42 in CSF samples70.

The SIMOA platform exhibits high sensitivity for detecting key AD biomarkers. SIMOA achieves a LOD of: 1.51 pg/mL for Aβ1–42, 4.08 pg/mL for Aβ1–40, and 0.338 pg/mL for p-tau181. Additionally, neurofilament light (NfL), a biomarker of neuronal damage found in both blood and CSF, is detectable with an LOD of 1.6 pg/mL with SIMOA71.

Other methods, such as FRET-based sensors, provide high sensitivity for a range of AD biomarkers, including Aβ peptides, tau protein, Presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and microRNA-125b (miR-125b). FRET can identify tau protein at femtomolar levels in brain homogenates72, and Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF), a FRET-based technique, can detect Aβ42 at a limit of 9 pg/mL73. FRET has also been applied to study Presenilin 1 (PSEN1), a protein associated with early-stage AD, with an LOD of 0.517 pM74 and can also measure acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter involved in learning and memory, at a limit of detection of 0.03226 nM74. FRET has also been used to detect miR-125b, a microRNA linked to neuron apoptosis and tau phosphorylation, with a limit of detection of 416.42 pM in TRIS-EDTA buffer75.

SPR and LSPR biosensors are also effective for detecting AD. For Aβ-42, SPR has achieved a detection limit of 100 pg/mL76, 14 fM for tau4477, and 34 fM for p-tau18177. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), a genetic factor strongly associated with AD risk, is similarly detectable with SPR at a concentration of 10 fM over a linear range from 10 fM to 1 pM78. For LSPR, a study reported detection limits of 26 fM for Aβ1-42, 34.9 fM for Aβ1-40, and 23.6 fM for tau protein using a shape-coded nanoplasmonic biosensor79.

SERS further enables ultra-sensitive detection of AD biomarkers. For Aβ-42 and Aβ-40, SERS has achieved LODs of 40 fM, 191.2 fg/mL respectively40,80. For tau-441, SERS has demonstrated an LOD of 8.7 pg/mL81. This high sensitivity allows for the detection of AD biomarkers, such as Aβ-42 monomers and fibrils, at 0.0232 ng/mL and 0.0192 ng/mL, respectively82, and NfL levels down to 309.1 fg/mL in AD studies40.

Finally, optical WGM resonators, such as FLOWER (frequency-locked optical whispering evanescent resonator) sensor, offer real-time, highly sensitive monitoring of Aβ-42 in CSF. By combining microtoroid resonators with frequency locking and balanced detection, FLOWER can differentiate between mild cognitive impairment (MCI), AD, and control groups. FLOWER has a lower LOD than ELISA, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92, compared to 0.82 for ELISA83.

PD detection

Over recent years, several PD biomarkers have been identified and used for early diagnostics. Among these, alpha-synuclein (α-synuclein) is a key protein that aggregates into Lewy bodies in the brains of PD patients, disrupting cellular function and leading to neuron death. Quantifying α-synuclein levels has become central to PD detection. Table 2 summarizes the sensitivity of various optical biosensing techniques used for PD biomarkers.

Colorimetric ELISA has been used to sense α-synuclein oligomers at a concentration of 0.25 ng/mL in PBS84. In addition, colorimetric ELISA has been applied to detect proteins associated with PD pathology, such as PARK7/DJ185 and PARK286, which are linked to oxidative stress and mitochondrial function. Commercially available assays have achieved a LOD of 15.6 pg/mL for PARK7/DJ185 and 0.156 ng/mL for PARK286. Using a sandwich ELISA, researchers have also measured ubiquitin phosphorylated at Ser65 (p-S65-Ub), which plays a role in mitophagy and is involved in mitochondrial dysfunction—a key feature in PD and other NDDs. Mitochondrial dysfunction in PD is intricately linked to α-synuclein, and elevated levels of p-S65-Ub may impact α-synuclein levels indirectly. ELISA assays have achieved sensitivity for p-S65-Ub in the femtomolar to picomolar range, depending on the poly-Ub chain linkage used87. The SIMOA platform has demonstrated plasma α-synuclein detection at 0.955 pg/mL88.

FRET-based techniques have also been applied to detect α-synuclein oligomers, with detection limits as low as 6.3 nM and two linear response ranges: from 10 nM to 100 nM and 250 nM to 2 μM89. The sensitivity can be extended to picomolar concentrations with single-molecule FRET. FRET assays have also shown that Ser129 phosphorylation (pS129) promotes α-synuclein oligomer aggregation90.

Label-free optical biosensors, such as SPR and LSPR, also play critical roles in PD detection. Conventional SPR has been used to quantify dopamine (DA) in CSF with an LOD of 0.1 ng/mL (653 pM) and a linear detection range from 0.01 to 189 μg/mL91. By enhancing SPR with graphene oxide (GO), GO-SPR has achieved greater sensitivity for DA detection, reaching an LOD of 100 fM with a range from 100 fM to 1 nM92. Beyond DA, a paired antibody and label-free Fe₃O₄-enhanced SPR platform has enabled α-synuclein detection with an LOD of 5.6 fg/mL over a linear range of 0.01 pg/mL to 100 pg/mL93. Typical LSPR systems can detect α-synuclein fibrils at concentrations of 70 nM94 and 80 nM95. With advancements such as gold nanoparticle aggregation, triggered by Cu²⁺ binding to α-synuclein, LSPR-based detection of α-synuclein in saliva has achieved a sensitivity of 10 nM, with a dynamic range of 10 to 200 nM26. Other LSPR enhancements, like mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA)-capped gold nanorods, allow for α-synuclein oligomer detection in PBS with an LOD of 11 pM96.

Recent advances in SERS have enhanced PD diagnostic capabilities. Using zinc oxide (ZnO)-enhanced SERS, researchers have detected DA in artificial CSF with a LOD of 10 μM97. With gold nanoparticle enhancement, SERS enables detection of 5-S-cysteinyl-dopamine, a DA oxidation metabolite, at concentrations as low as 10 nM in synthetic CSF and 100 nM in simulated urine98. Recent developments in SERS-based lab-on-chip platforms allow simultaneous quantification of PD biomarkers like α-synuclein, p-tau-181, osteopontin (OPN), and osteocalcin (OCN), each within a range from 1 pg/mL to 1 μg/mL99. OPN and OCN play critical roles in PD pathology: OPN is associated with neuroinflammation, a key process in PD, while OCN has been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier and influence brain function100.

Other NDD detection

Beyond AD and PD, NDDs encompass a broad spectrum of disorders, each characterized by unique mechanisms, affected brain regions, progression rates, and clinical symptoms. These include Huntington’s Disease (HD), Prion diseases, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA)101.

These conditions have become key research areas due to their significant disease burden, well-defined genetic bases, and the availability of animal models. Despite their shared feature of progressive neuronal degeneration causing motor and cognitive impairments, each disease arises from distinct molecular and genetic mechanisms. For instance, Huntington’s Disease is caused by a mutation in the HTT gene, leading to an abnormal huntingtin protein102. Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) results from mutations in the SMN1 gene, affecting the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein103. Prion Diseases arise from the misfolding of prion proteins (PrP), resulting in infectious neurodegeneration104. Optical biosensors have become tools for detecting these diseases, focusing on biomarkers related to protein misfolding and aggregation, providing opportunities for early diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Table 3 presents a detailed comparison of biosensor detection limits for a range of NDD biomarkers beyond AD and PD.

ELISA assays have been widely used to detect biomarkers across various NDDs. In FTD, AD, and subjective cognitive decline, ELISA has measured NfL in CSF with a LOD of 100 pg/mL105. In Huntington’s disease (HD), ELISA is used in combination with Western blotting to detect antibodies against the huntingtin protein (HTT/mHTT) in human plasma, achieving a sensitivity of up to 2.7 fmol per well106. For Prion diseases, ELISA can detect abnormal prion protein isoforms (PrPSC) in cell cultures across a one log dynamic range107. In SMA, ELISA targeting SMN protein has achieved a sensitivity of 50 pg/mL108, and in ALS, ELISA can detect TDP-43 protein (TAR NDA-binding protein 43), a key factor for ALS detection due to its aggregation in neurons found in ALS patients, at a level of 0.49 ng/mL109.

The SIMOA platform has also been used for other NDD biomarker detection. SIMOA can detect NfL at sub-picogram/mL concentrations, thus enabling detection of ALS110, Prion disease111, MSA112, and SCA113. For FTD, SIMOA has achieved sensitivity down to sub-picogram per milliliter when targeting TDP-43114.

FRET biosensors have been used to diagnose other NDDs as well. In HD, FRET-based assays, such as the FRET-based protein aggregate seeding assay (FRASE), detected HTT protein aggregates at femtomolar levels115. FRET has also been applied to ALS diagnostics by targeting TDP-43, with integration into glucose sensors to measure glucose flux, showing altered FRET/CFP ratios in TDP-43-expressing neurons, indicative of heightened glucose metabolism116. For Prion disease, FRET methods, including live-cell FRET imaging117 and high-throughput screening118, have enabled PrP clustering detection at the cell surface. Additionally, TR-FRET has detected soluble ataxin-3 protein in SCA type 3119 and was able to capture the decrease in soluble ataxin-3 protein corresponding to disease progression. Quantification of ataxin-2 protein for SCA type 2 using TR-FRET-based immunoassays has demonstrated sensitivity down to 7.995 ng/μL120. In addition, commercial kits, such as the HTRF Human and Mouse Ataxin 2 Detection Kit, have been developed for the quantitative measurement of ataxin-2 in human and mouse cell lysates. This kit offers a detection limit of 7 pg/mL and a dynamic range from 21 to 10,000 pg/mL121.

Label-free techniques like SPR, LSPR, and SERS have also been applied to other NDD diagnostics. SPR has been effectively used in HD research to study thioredoxin-polyQ fusion proteins, which are associated with mutations in the HTT gene linked to HD. In E. coli, this approach has been used to measure the binding affinity between specific peptides containing an expanded polyQ stretch, which was determined to be 5.7 μM122. SPR has also been utilized in Prion disease studies, detecting PrPSc at concentrations as low as 0.001 ng/mL123. SPR has facilitated the study of age-dependent ataxia and NDDs by targeting mutant mice models, αII spectrin, a protein playing a crucial role in maintaining the structural integrity and function of neurons, and found the degradation of αII spectrin in cerebral tissue correlating with disease124. LSPR can detect SOD1, a critical ALS biomarker, at 1.0 ng/mL125. LSPR enables the quantification of dopamine in CSF with a detection limit of 1 pM and a dynamic range of 1 pM to 10 nM126. This capability makes LSPR a valuable tool for studying NDDs such as PD and HD. For broader neurological diagnostics, LSPR has targeted biomarkers such as Immunoglobulin G (IgG), C-reactive protein (CRP), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). Detection limits have been achieved at approximately 0.017 μg/mL for IgG127, 87 pg/mL for CRP128, 90 fg/mL for TNF-α129, and 11.29 pg/mL for IL-6130.

SERS biosensors have also demonstrated applicability across multiple NDDs. In HD, SERS has been used to monitor protein misfolding markers and nucleotide catabolism products in serum131. ALS diagnostics with SERS have benefitted from the use of gold nanostars, achieving ultra-sensitive detection of SOD1 in blood with an LOD of 0.564 fg/mL and a wide detection range from 10⁻⁴ ng/mL to 10³ ng/mL132. For Prion diseases, SERS has achieved high performance in detecting PrP protein with an LOD of 250 nM133. Additionally, spread spectrum SERS (ss-SERS), has enabled the detection of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine (ACh), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and glutamate, with attomolar-level sensitivity134.

Conclusions and future outlook

This review highlights the critical role of optical biosensors in detecting NDDs, presenting their sensitivity and selectivity across various sample types, including CSF, blood, serum, plasma, simulated urine, and saliva. Beyond diagnostics, these biosensors hold promise for identifying novel biomarkers, addressing the current lack of disease-specific markers, and enabling earlier detection of NDDs. Future advancements in optical biosensors focus on enhancing sensitivity through improved materials for technologies like SERS, SPR, LSPR, and FLOWER. Integrating multiplexing capabilities will enable simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers, while incorporating artificial intelligence can further enhance accuracy and efficiency. Moreover, optical microcavities can generate on-chip frequency combs, enabling spectroscopic analysis to detect and differentiate biomarkers associated with these conditions in complex fluids. In addition to these innovations, transitioning optical biosensors to point-of-care applications and commercialization will facilitate wider clinical use, making diagnostics faster, more accessible, and cost-effective. While this review focuses on optical biosensors, advancements in complementary methodologies like wireless quartz crystal microbalances (QCM) have demonstrated potential in differentiating fibrils from PD and multiple system atrophy by identifying differences in mechanical properties such as stiffness135,136. By addressing current challenges and expanding their capabilities, these technologies will significantly improve early detection and monitoring, advancing patient outcomes and our understanding of NDDs.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Staff, C. on L. S. Opportunities in Biology (National Academies Press, Washington, 1988).

Dutta, R. & Trapp, B.D. Mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction and degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Prog. Neurobiol. 93, 1–12 (2011).

Davis, S.E., Cirincione, A.B., Jimenez-Torres, A.C. & Zhu, J. The impact of neurotransmitters on the neurobiology of neurodegenerative diseases. IJMS 24, 15340 (2023).

Lamptey, R.N.L. et al. A review of the common neurodegenerative disorders: current therapeutic approaches and the potential role of nanotherapeutics. IJMS 23, 1851 (2022).

Culig, L., Chu, X. & Bohr, V.A. Neurogenesis in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 78, 101636 (2022).

Chopade, P. et al. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease therapies in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 8, e10367 (2023).

2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 20, 3708–3821 (2024).

NIH. Parkinson’s Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Promise. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/current-research/focus-disorders/parkinsons-disease-research/parkinsons-disease-challenges-progress-and-promise (2023).

Mendez, M.F. Early-onset Alzheimer disease and its variants. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 25, 34–51 (2019).

Alzheimer Disease and APOE e4: Practice Essentials, Clinical Implications (2022).

Djekidel, M. & Das, J. M. Nuclear Medicine Neuro PET Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, 2024).

MCD. FDG PET for Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases (220.6.13). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=288&ncdver=3& (2009).

Review Highlights Role of OCT-A in Neurodegenerative Diseases. AJMC https://www.ajmc.com/view/review-highlights-role-of-oct-a-in-neurodegenerative-diseases (2020).

Eberling, J.L. & Jagust, W.J. Imaging studies of aging, neurodegenerative disease, and alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res. World 19, 279 (1995).

Loftus, J.R., Puri, S. & Meyers, S.P. Multimodality imaging of neurodegenerative disorders with a focus on multiparametric magnetic resonance and molecular imaging. Insights Imaging 14, 8 (2023).

Stoessl, A.J. Neuroimaging in the early diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 1, 5 (2012).

Sorby-Adams, A.J. et al. Portable, low-field magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 10488 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Miniaturized head-mount doppler optical coherence tomography scope for freely moving mouse. ACS Photonics 11, 3381–3389 (2024).

Bodaghi, A., Fattahi, N. & Ramazani, A. Biomarkers: promising and valuable tools towards diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of COVID-19 and other diseases. Heliyon 9, e13323 (2023).

Sheinerman, K.S., Tsivinsky, V.G., Abdullah, L., Crawford, F. & Umansky, S.R. Plasma microRNA biomarkers for detection of mild cognitive impairment: biomarker validation study. Aging5, 925 (2013).

Mo, M. Editorial: non-coding RNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1241737 (2023).

Ehrenberg, A.J. et al. Relevance of biomarkers across different neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer’s. Res. Ther. 12, 56 (2020).

Singh, A.K., Mittal, S., Das, M., Saharia, A. & Tiwari, M. Optical biosensors: a decade in review. Alex. Eng. J. 67, 673–691 (2023).

Bhalla, N., Jolly, P., Formisano, N. & Estrela, P. Introduction to biosensors. Essays Biochem. 60, 1 (2016).

Flynn, C.D. & Chang, D. Artificial intelligence in point-of-care biosensing: challenges and opportunities. Diagnostics 14, 1100 (2024).

Mottaghi, A., Nikkhah, M. & Masroor, M.J. Lable-free LSPR-based colorimetric detection of α-synuclein, a biomarker of Parkinson’s disease, in saliva. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 5713–5719 (2023).

Gaetani, L. et al. A new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for neurofilament light in cerebrospinal fluid: analytical validation and clinical evaluation. Alzheimer’s. Res. Ther. 10, 8 (2018).

Sung, W.-H., Hung, J.-T., Lu, Y.-J. & Cheng, C.-M. Paper-based detection device for Alzheimer’s disease-detecting β-amyloid peptides (1-42) in human plasma. Diagnostics10, 272 (2020).

Thiha, A. & Ibrahim, F. A colorimetric enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detection platform for a point-of-care dengue detection system on a lab-on-compact-disc. Sensors15, 11431–11441 (2015).

Rissin, D.M. et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 595 (2010).

Wilson, D.H. et al. The simoa HD-1 analyzer: a novel fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer with single-molecule sensitivity and multiplexing. SLAS Technol. 21, 533–547 (2016).

Kumaran, A. et al. Advancements in CRISPR-based biosensing for next-gen point of care diagnostic application. Biosensors 13, 202 (2023).

Verma, A.K., Noumani, A., Yadav, A.K. & Solanki, P.R. FRET based biosensor: principle applications recent advances and challenges. Diagnostics 13, 1375 (2023).

Piliarik, M., Vaisocherová, H. & Homola, J. Surface plasmon resonance biosensing. In: Biosensors and Biodetection (eds. Rasooly, A. & Herold, K. E.) 65–88 (Humana Press, Totowa, 2009); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-567-5_5.

XanTec bioanalytics GmbH. Tech Notes. Optics. https://www.xantec.com/technotes/optics.php.

Sepúlveda, B., Angelomé, P.C., Lechuga, L.M. & Liz-Marzán, L.M. LSPR-based nanobiosensors. Nano Today 4, 244–251 (2009).

Nguyen, P.-D., Zhang, X. & Su, J. One-step controlled synthesis of size-tunable toroidal gold particles for biochemical sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 7839–7847 (2019).

Cara, E. et al. Towards a traceable enhancement factor in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 16513–16519 (2020).

Heeg, S., Mueller, N.S., Wasserroth, S., Kusch, P. & Reich, S. Experimental tests of surface-enhanced Raman scattering: moving beyond the electromagnetic enhancement theory. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 310–322 (2021).

Zhan, Y. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of multiple Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers by SERS-LFA. Analyst 147, 4124–4131 (2022).

Hao, S. & Su, J. Whispering gallery mode optical resonators for biological and chemical detection: current practices, future perspectives, and challenges. Rep. Prog. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6633/ad99e7 (2024).

Baaske, M.D., Foreman, M.R. & Vollmer, F. Single-molecule nucleic acid interactions monitored on a label-free microcavity biosensor platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 933–939 (2014).

Bryan, M.R., Butt, J.N., Bucukovski, J. & Miller, B.L. Biosensing with silicon nitride microring resonators integrated with an on-chip filter bank spectrometer. ACS Sens 8, 739–747 (2023).

Su, J. Label-free single exosome detection using frequency-locked microtoroid optical resonators. ACS Photonics 2, 1241–1245 (2015).

Dell’Olio, F. et al. Photonic technologies for liquid biopsies: recent advances and open research challenges. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000255 (2021).

Hao, S., Suebka, S. & Su, J. Single 5-nm quantum dot detection via microtoroid optical resonator photothermal microscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 195 (2024).

Hao, S. & Su, J. Noise-induced limits of detection in frequency locked optical microcavities. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 6393–6401 (2020).

Hao, S. et al. Steviol rebaudiosides bind to four different sites of the human sweet taste receptor (T1R2/T1R3) complex explaining confusing experiments. Commun. Chem. 7, 1–17 (2024).

Young Yang, M. et al. Agonist activation to open the Gα subunit of the GPCR–G protein precoupled complex defines functional agonist activation of TAS2R5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2409987121 (2024).

Yoo, K. M. et al. Lab-on-a-chipoptical biosensor platform: a micro-ring resonator integrated with a near-infrared Fourier transform spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 48, 5371–5374 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. A label-free optical biosensor based on an array of microring resonators for the detection of human serum albumin. Sensors 24, 677 (2024).

Lo, S.M. et al. Photonic crystal microring resonator for label-free biosensing. Opt. Express25, 7046–7054 (2017).

Suebka, S., Gin, A. & Su, J. Frequency locked whispering evanescent resonator (FLOWER) for biochemical sensing applications. Nat Protoc. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01096-7 (2025).

Su, J., Goldberg, A. & Stoltz, B. Label-free detection of single nanoparticles and biological molecules using microtoroid optical resonators. Light Sci Appl. 5, e16001 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Low Part-Per-Trillion, Humidity Resistant Detection of Nitric Oxide Using Microtoroid Optical Resonators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c16012 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Part-per-Trillion Trace Selective Gas Detection Using Frequency Locked Whispering-Gallery Mode Microtoroids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 42430–42440 (2022).

Ozgur, E. et al. Ultrasensitive Detection of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Using Frequency Locked Microtoroid Optical Resonators. Anal. Chem. 91, 11872–11878 (2019).

Luu, G. T. et al. An Integrated Approach to Protein Discovery and Detection From Complex Biofluids. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 22, (2023).

Chen, L., Li, C., Liu, Y., Su, J. & McLeod, E. Three-Dimensional Simulation of Particle-Induced Mode Splitting in Large Toroidal Microresonators. Sensors 20, 5420 (2020).

Gin, A. et al. Label-free, real-time monitoring of membrane binding events at zeptomolar concentrations using frequency-locked optical microresonators. Nat. Commun. 15, 7445 (2024).

Suebka, S., Nguyen, P.-D., Gin, A. & Su, J. How fast it can stick: visualizing flow delivery to microtoroid biosensors. ACS Sens 6, 2700–2708 (2021).

Suebka, S., McLeod, E. & Su, J. Ultra-high-Q free-space coupling to microtoroid resonators. Light Sci. Appl 13, 75 (2024).

Choi, G., Gin, A., Su, J. & Su, J. Optical frequency combs in aqueous and air environments at visible to near-IR wavelengths. Opt. Express30, 8690–8699 (2022).

Choi, G. & Su, J. Impact of stimulated raman scattering on DarkSoliton generation in a silica microresonator. J. Phys. Photonics. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7647/aca8e1 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Dong, H., Liu, L. & Xu, M. Simple colorimetric detection of amyloid β-peptide (1-40) based on aggregation of gold nanoparticles in the presence of copper ions. Small 11, 2144–2149 (2015).

Humpel, C. Identifying and validating biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Biotechnol. 29, 26–32 (2011).

Tarawneh, R. et al. Visinin-like protein-1: diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 70, 274 (2011).

Mehta, P.D., Patrick, B.A., Miller, D.L., Coyle, P.K. & Wisniewski, T. A sensitive and cost-effective chemiluminescence ELISA for measurement of amyloid-β 1–42 peptide in human plasma. J. Alzheimer’s. Dis.78, 1237 (2020).

Pais, M. V., Forlenza, O. V. & Diniz, B. S. Plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of available assays, recent developments, and implications for clinical practice. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 7, 355–380 (2023).

Jia, Z. et al. CRISPR-powered aptasensor for diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Sens. 9, 398–405 (2024).

Chatterjee, P. et al. Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, p-tau181, GFAP, and NfL across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study in the AIBL cohort. Alzheimer’s. Dement. 19, 1117–1134 (2023).

Holmes, B.B. et al. Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4376–E4385 (2014).

Revvity. HTRF Human Amyloid β 1-42 Detection Kit, 500 Assay Points (Product No. 62B42PEG). Revvity Life Sciences. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.revvity.com/product/htrf-hu-amyloid-b1-42-kit-500-pts-62b42peg.

Wang, X.Z. et al. Driving force to detect Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: application of a thioflavine T@Er-MOF ratiometric fluorescent sensor for smart detection of presenilin 1, amyloid β-protein and acetylcholine. Analyst 145, 4646–4663 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. A dual “turn-on” biosensor based on AIE effect and FRET for in situ detection of miR-125b biomarker in early Alzheimer’s disease. Biosens. Bioelectron. 230, 115270 (2023).

Lee, Y.K., Lee, K.-S., Kim, W.M. & Sohn, Y.-S. Detection of amyloid-β42 using a waveguide-coupled bimetallic surface plasmon resonance sensor chip in the intensity measurement mode. PLoS One 9, e98992 (2014).

Chan, H.-N., Xu, D., Ho, S.-L., Shing Wong, M. & Li, H.-W. Ultra-sensitive detection of protein biomarkers for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Sci. 8, 4012–4018 (2017).

Yi, X. et al. Dual-channel surface plasmon resonance for quantification of ApoE gene and genotype discrimination in unamplified genomic DNA extracts. ACS Sens. 3, 2402–2407 (2018).

Kim, H., Lee, J.U., Song, S., Kim, S. & Sim, S.J. A shape-code nanoplasmonic biosensor for multiplex detection of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 101, 96–102 (2018).

Gao, F. et al. SERS-based optical nanobiosensors for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Biosensors13, 880 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Self-assembly of Au nanocubes for ultrasensitive detection of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers by SERS. Anal. Methods 15, 6385–6393 (2023).

Wang, L., Chen, H., Ma, S., Chang, M. & Zhang, X. Ultra-sensitive SERS detection of Aβ 1–42 for Alzheimer’s disease using graphene oxide/gold nanohybrids. Vib. Spectrosc. 129, 103614 (2023).

Gin, A., Nguyen, P.-D., Serrano, G., Alexander, G.E. & Su, J. Towards early diagnosis and screening of Alzheimer’s disease using frequency locked whispering gallery mode microtoroids. npj Biosensing 1, 9 (2024).

Lassen, L.B. et al. ELISA method to detect α-synuclein oligomers in cell and animal models. PLoS One 13, e0196056 (2018).

Human PARK7/DJ1 ELISA Kit (ABIN6999500). https://www.antibodies-online.com/kit/6999500/Parkinson+Protein+7+PARK7+ELISA+Kit/.

Human Parkinson's Disease Protein 2 (PARK2) ELISA Kit, Cat#EKU06492. Biomatik https://www.biomatik.com/elisa-kits/human-parkinson-disease-protein-2-park2-elisa-kit-cat-eku06492/.

Watzlawik, J.O. et al. Sensitive ELISA-based detection method for the mitophagy marker p-S65-Ub in human cells, autopsy brain, and blood samples. Autophagy 17, 2613 (2020).

Ng, A.S.L. et al. Plasma alpha-synuclein detected by single molecule array is increased in PD. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6, 615–619 (2019).

Saedi, Z. & Nikkhah, M. A FRET-based aptasensor for the detection of α-synuclein oligomers as biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Anal. Methods 14, 2937–2944 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. Rapid FRET assay for the early detection of alpha-synuclein aggregation in Parkinson’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 15, 1378–1387 (2024).

Jabbari, S., Dabirmanesh, B., Daneshjou, S. & Khajeh, K. The potential of a novel enzyme-based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for direct detection of dopamine. Sci. Rep. 14, 14303 (2024).

Kamal Eddin, F.B. et al. Development of plasmonic-based sensor for highly sensitive and selective detection of dopamine. Opt. Laser Technol. 161, 109221 (2023).

Mandala, S.H.S. et al. Enhanced plasmonic biosensor utilizing paired antibody and label-free Fe3O4 nanoparticles for highly sensitive and selective detection of Parkinson’s α-synuclein in serum. Biosensors 11, 402 (2021).

Khatri, A., Punjabi, N., Ghosh, D., Maji, S. & Mukherji, S. Detection of α-synuclein, marker for parkinson’s disease using localized surface plasmon resonance fiber optic sensor. In 12th International Conference on Fiber Optics and Photonics (2014), Paper M4A.45 M4A.45 (Optica Publishing Group, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1364/PHOTONICS.2014.M4A.45.

Kumar, J. et al. Detection of amyloid fibrils in Parkinson’s disease using plasmonic chirality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA115, 3225–3230 (2018).

Apaydın, B. B. et al. Chitosan-enhanced sensitivity of mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA)- capped gold nanorod based localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) biosensor for detection of alpha-synuclein oligomer biomarker in parkinson’s disease. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2653 (2024).

Colniță, A. et al. SERS detection of dopamine in artificial cerebrospinal fluid and in Parkinson’s disease-induced mouse cortex using a hybrid ZnO@Ag nanostructured platform. Microchem. J. 206, 111589 (2024).

Badillo-Ramírez, I., Landeros-Rivera, B., Saniger, J.M., Popp, J. & Cialla-May, D. SERS-based detection of 5- S -cysteinyl-dopamine as a novel biomarker of Parkinson’s disease in artificial biofluids. Analyst 148, 1848–1857 (2023).

Cao, X., Ge, S., Chen, M., Mao, H. & Wang, Y. LoC-SERS Platform Integrated with the Signal Amplification Strategy toward Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 21830–21842 (2023).

Shan, C. et al. Osteocalcin ameliorates cognitive dysfunctions in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease by reducing amyloid β burden and upregulating glycolysis in neuroglia. Cell Death Discov. 9, 1–12 (2023).

U.S. National Library of Medicine. Degenerative Nerve Diseases. MedlinePlus. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/degenerativenervediseases.html.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Huntington’s Disease. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/huntingtons-disease.

Keinath, M.C., Prior, D.E. & Prior, T.W. Spinal muscular atrophy: mutations, testing, and clinical relevance. Appl Clin. Genet. 14, 11–25 (2021).

Moore, R.A., Taubner, L.M. & Priola, S.A. Prion protein misfolding and disease. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 14–22 (2009).

Das, S. et al. A novel neurofilament light chain ELISA validated in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and subjective cognitive decline, and the evaluation of candidate proteins for immunoassay calibration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7221 (2022).

Massai, L. et al. Development of an ELISA assay for the quantification of soluble huntingtin in human blood cells. BMC Biochem. 14, 34 (2013).

Shan, Z., Yamasaki, T., Suzuki, A., Hasebe, R. & Horiuchi, M. Establishment of a simple cell-based ELISA for the direct detection of abnormal isoform of prion protein from prion-infected cells without cell lysis and proteinase K treatment. Prion 10, 305–318 (2016).

Kobayashi, D.T. et al. Utility of survival motor neuron ELISA for spinal muscular atrophy clinical and preclinical analyses. PLoS One6, e24269 (2011).

Kasai, T. et al. Increased TDP-43 protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 117, 55–62 (2009).

Verde, F., Otto, M. & Silani, V. Neurofilament light chain as biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Front. Neurosci. 15, 679199 (2021).

Thompson, A.G.B. et al. Evaluation of plasma tau and neurofilament light chain biomarkers in a 12-year clinical cohort of human prion diseases. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 5955–5966 (2021).

Singer, W. et al. Neurofilament light chain in spinal fluid and plasma in multiple system atrophy—a prospective, longitudinal biomarker study. Res Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3201386/v1 (2023).

Shin, H.-R. et al. Serum neurofilament light chain as a severity marker for spinocerebellar ataxia. Sci. Rep. 11, 13517 (2021).

Quanterix. TDP-43 Assay. 2025. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.quanterix.com/simoa-assay-kits/tdp-43/.

Schindler, F. et al. Small, seeding-competent huntingtin fibrils are prominent aggregate species in brains of zQ175 Huntington’s disease knock-in mice. Front. Neurosci. 15, 682172 (2021).

Manzo, E. et al. Glycolysis upregulation is neuroprotective as a compensatory mechanism in ALS. eLife 8, e45114 (2019).

Tavares, E. et al. Live-cell FRET imaging reveals clustering of the prion protein at the cell surface induced by infectious prions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1842, 981–991 (2014).

Karapetyan, Y.E. et al. Unique drug screening approach for prion diseases identifies tacrolimus and astemizole as antiprion agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA110, 7044–7049 (2013).

Nguyen, H.P. et al. Cerebellar Soluble Mutant Ataxin-3 Level Decreases during Disease Progression in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 Mice. PLoS One8, e62043 (2013).

Bux, J. et al. TR-FRET-based immunoassay to measure Ataxin-2 as a target engagement marker in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Mol. Neurobiol. 60, 3553–3567 (2023).

Revvity. HTRF Human & Mouse Ataxin 2 Detection Kit, 500 Assay Points (Product No. 64ATA2PEG). Revvity Life Sciences. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.revvity.com/product/htrf-h-m-ataxin-2-kit-500-pts-64ata2peg.

Okamoto, Y. et al. Surface plasmon resonance characterization of specific binding of polyglutamine aggregation inhibitors to the expanded polyglutamine stretch. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 634–639 (2009).

Lou, Z. et al. Quick and sensitive SPR detection of prion disease-associated isoform (PrPSc) based on its self-assembling behavior on bare gold film and specific interactions with aptamer-graphene oxide (AGO). Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 157, 31–39 (2017).

Miazek, A. et al. Age-dependent ataxia and neurodegeneration caused by an αII spectrin mutation with impaired regulation of its calpain sensitivity. Sci. Rep. 11, 7312 (2021).

Hong, S., Lee, S. & Yi, J. Sensitive and molecular size-selective detection of proteins using a chip-based and heteroliganded gold nanoisland by localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 336 (2011).

Pagano, R. et al. Localized and surface plasmons coupling for ultrasensitive dopamine detection by means of SPR-based perylene bisimide/Au nanostructures thin film. Adv. Mater. Inter. 8, 2101023 (2021).

Zhang, A., Li, Z., Chang, P., Shi, Y. & Wang, Z. High sensitivity rabbit IgG biosensor co-enhanced by tapered noncore fiber and coupling effect between SPR and LSPR. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 193701 (2024).

Ha, S.-J., Park, J.-H., Byun, J.-Y., Ahn, Y.-D. & Kim, M.-G. A localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) immunosensor for CRP detection using 4-chloro-1-naphtol (4-CN) precipitation. 10324, 103240E (2017).

Singh, M., Truong, J., Reeves, W.B. & Hahm, J. Emerging cytokine biosensors with optical detection modalities and nanomaterial-enabled signal enhancement. Sensors 17, 428 (2017).

Majdinasab, M., Lamy de la Chapelle, M. & Marty, J.L. Recent progresses in optical biosensors for interleukin 6 detection. Biosensors13, 898 (2023).

Huefner, A., Kuan, W.-L., Mason, S.L., Mahajan, S. & Barker, R.A. Serum Raman spectroscopy as a diagnostic tool in patients with Huntington’s disease. Chem. Sci. 11, 525–533 (2020).

Gao, F. et al. SERS “hot spot” enhance-array assay for misfolded SOD1 correlated with white matter lesions and aging. Anal. Chim. Acta 1238, 340163 (2023).

Singh, S., Agarwal, A., Avni, A. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Ultrasensitive characterization of the prion protein by surface-enhanced raman scattering: selective enhancement via electrostatic tethering of the intrinsically disordered domain with functionalized silver nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 3187–3194 (2021).

Lee, W. et al. Spread spectrum SERS allows label-free detection of attomolar neurotransmitters. Nat. Commun. 12, 159 (2021).

Ogi, H., Motoshisa, K., Matsumoto, T., Hatanaka, K. & Hirao, M. Isolated electrodeless high-frequency quartz crystal microbalance for immunosensors. Anal. Chem. 78, 6903–6909 (2006).

Zhou, L. et al. Ultrastiff amyloid-fibril network of α-synuclein formed by surface seeding reaction confirmed by multichannel electrodeless quartz-crystal-microbalance biosensor. ACS Sens. 8, 2598–2608 (2023).

Bermejo-Pareja, F., Antequera, D., Vargas, T., Molina, J.A. & Carro, E. Saliva levels of Abeta1-42 as potential biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. BMC Neurol. 10, 108 (2010).

Acker, C.M., Forest, S.K., Zinkowski, R., Davies, P. & d’Abramo, C. Sensitive quantitative assays for tau and phospho-tau in transgenic mouse models. Neurobiol. aging 34, 338 (2012).

Abcam. Human Tau ELISA Kit, Fluorescent (Product No. ab229394). Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.abcam.com/en-us/products/elisa-kits/human-tau-elisa-kit-fluorescent-ab229394.

Truffi, M. et al. Neurofilament-light chain quantification by Simoa and Ella in plasma from patients with dementia: a comparative study. Sci. Rep. 13, 4041 (2023).

De Meyer, S. et al. Comparison of ELISA- and SIMOA-based quantification of plasma Aβ ratios for early detection of cerebral amyloidosis. Alz Res Ther. 12, 162 (2020).

Bayoumy, S. et al. Clinical and analytical comparison of six Simoa assays for plasma P-tau isoforms P-tau181, P-tau217, and P-tau231. Alz Res Ther. 13, 198 (2021).

Hitt, B.D. et al. Ultrasensitive tau biosensor cells detect no seeding in Alzheimer’s disease CSF. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 9, 99 (2021).

Xia, N., Liu, L., Harrington, M.G., Wang, J. & Zhou, F. Regenerable and simultaneous surface plasmon resonance detection of aβ(1-40) and aβ(1-42) peptides in cerebrospinal fluids with signal amplification by streptavidin conjugated to an N-terminus-specific antibody. Anal. Chem. 82, 10151–10157 (2010).

Nangare, S. & Patil, P. Poly(allylamine) coated layer-by-layer assembly decorated 2D carbon backbone for highly sensitive and selective detection of Tau-441 using surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 1271, 341474 (2023).

Vestergaard, M., Kerman, K., Kim, D.-K., Ha, M.H. & Tamiya, E. Detection of Alzheimer’s tau protein using localised surface plasmon resonance-based immunochip. Talanta 74, 1038–1042 (2008).

Tosatto, L.et al. Single-molecule FRET studies on alpha-synuclein oligomerization of Parkinson’s disease genetically related mutants. Sci. Rep. 5, 16696 (2015).

Bouteloup, V. et al. Explaining the variability of Alzheimer's disease fluid biomarker concentrations in memory clinic patients without dementia. Neurology 102, e209219 (2024).

Quanterix. Simoa Assay Kits. Accessed April 10, 2025. Available at: https://www.quanterix.com/simoa-assay-kits/.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support in part from NIH R35GM137988.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D.M. conducted the literature review and wrote the initial manuscript draft. J.S. provided input, edited the manuscript, and guided the structure and focus of the article. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.S. owns a financial stake in Femtorays Technologies, which develops label-free molecular sensors. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duy Mac, K., Su, J. Optical biosensors for diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases. npj Biosensing 2, 20 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00040-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00040-3

This article is cited by

-

Future directions in all-optical label-free single-molecule sensing

npj Biosensing (2026)

-

All-Optical Plasmonic Neurosensor for Self-Learning Anomaly Detection in Smart IoT Systems

Plasmonics (2026)

-

A comprehensive review on the integration of microneedle technologies with biosensing platforms for advancements in fabrication, biomarker detection, and therapeutic monitoring in precision medicine

Discover Pharmaceutical Sciences (2025)