Abstract

Sleep disorders affect millions globally, leading to serious health issues. Accurate sleep-wake classification is essential for diagnosis and management. While polysomnography is the gold standard, it is costly and invasive; photoplethysmography (PPG) offers a viable alternative. Using the Cyclic Alternating Pattern Sleep Database (84 participants, 85,542 epochs), we extracted 330 features and reduced dimensionality via statistical tests and the SelectFromModel method. To address class imbalance, we applied Adaptive Synthetic (ADASYN) sampling. A Random Forest model, validated with 20-fold cross-validation on the unbalanced dataset (75 features), achieved an F1 score of 89.05% but struggled with wake detection. With ADASYN balancing and 35 features, it achieved 88.57% sensitivity (sleep) and 71.31% specificity (wake), with an F1 score of 81.40%. This feature-based approach improves PPG-based sleep classification, supporting clinical adoption and integration into wearable devices for remote sleep monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sufficient sleep is vital for maintaining good physical and mental health, yet a significant proportion of adults worldwide suffer from sleep deficiencies and disorders. In the United States, one-third of adults experience inadequate sleep1, and globally, sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea affect an estimated 936 million adults2. These sleep issues lead to various health problems, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and mental health disorders3. Accurate sleep-wake detection is critical as it forms the basis for understanding, diagnosing, and treating sleep disorders. Disturbances in sleep-wake cycles can indicate conditions such as insomnia4,5,6, sleep apnea7, and restless legs syndrome8,9. However, detecting sleep-wake cycles remains challenging despite advancements in sleep monitoring.

Polysomnography (PSG) is the clinical gold standard for sleep monitoring, recording physiological parameters such as electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculogram (EOG), electromyogram (EMG), breathing effort, airflow, pulse, and blood oxygen saturation. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) provides the most widely used framework for sleep staging using PSG data, grouping sleep into four stages: N1, N2, N3, and rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep. N1 and N2 stages are often combined as light sleep (LS), while N3 is referred to as deep sleep (DS)10. Despite its precision, PSG is expensive, time-consuming, and requires an overnight lab stay with professional supervision and manual labeling, limiting its practicality. It also suffers from high inter-rater variability (82.6% agreement11), can disrupt natural sleep patterns, and fails to account for night-to-night variations12,13.

Actigraphy, using wrist-worn devices with accelerometers to estimate sleep based on inactivity, has become the accepted method for home-based sleep monitoring14,15. However, the Cole-Kripke algorithm16 used in actigraphy is only modestly successful, does not differentiate sleep stages, and can overestimate sleep due to motionless wakefulness17,18,19,20. Consumer wearables like Oura, WHOOP, Apple Watch, and Fitbit offer cost-effective home-based sleep staging, but fall short of clinical use due to a lack of transparency and access to raw data, hindering validation against PSG21.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is widely used in clinical and wearable devices for non-invasive cardiovascular monitoring. By using a light source and photodetector on the skin, PPG measures variations in light absorption with each heartbeat, reflecting changes in blood volume. The PPG waveform, with peaks corresponding to systolic and diastolic phases, reflects the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, which varies across sleep stages22,23. PPG’s ability to capture these variations makes it valuable for sleep staging. Additionally, its established clinical use24,25,26, makes PPG highly scalable and supports widespread application. PPG-based automatic sleep staging could provide a simple, cost-effective and accurate alternative to existing methods for sleep monitoring.

In the advancement of automatic sleep staging, the adoption of machine learning classifiers trained on PPG data is gaining traction. Previous research has employed various approaches, leveraging both publicly available and proprietary datasets. Using public datasets, such as the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS)27, the Cleveland Family Study (CFS)27, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)27, Emory twin study follow-up database (ETSF)28,29, the Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT)30, SIESTA (Study of Insomnia and Sleep Estimation)31,32,33,34, Sleep and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Monitoring with Non-Invasive Applications (SOMNIA)34,35,36 and the CAP (Cyclic Alternating Pattern) sleep database37, enhances the replicability and generalizability of findings. In contrast, a significant body of research38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 relies on proprietary data, limiting the wider applicability of the outcomes.

One significant challenge in sleep staging is the inherent imbalance in sleep stages, with wake constituting only about 20% of the sleep cycle and sleep stages making up the remaining 80%. This imbalance can lead to models being biased towards the majority stages, reducing their effectiveness in accurately detecting less prevalent stages. Only a few studies have addressed this issue through techniques such as data balancing or adjusting class weights27,28,39,45,46,51,58,60. Implementing these approaches before model training can significantly enhance the model’s generalizability and avoid bias, making them crucial steps often overlooked in previous studies.

The model inputs vary between studies, with some using feature-based approaches and others using PPG signals directly. Feature-based classifiers are particularly valuable for clinical PPG-based sleep staging. Compared to raw signal approaches27,30,34,40,41,42,51,52,59, feature-based classifiers offer enhanced interpretability and reduced computational demands. They also present the potential to identify biomarkers for different sleep stages. Studies have shown that feature-based models can capture the nuances of sleep and wake stages, making them suitable for clinical applications28,29,31,32,33,35,36,37,39,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,60,61.

The models used in PPG-based sleep staging vary, ranging from traditional machine learning algorithms32,37,38,43,44,47,48,49,50,53,55,56,57,58 to more complex deep learning approaches27,28,30,31,33,34,35,36,39,40,41,42,45,51,52,59,61. Although feature-based classifiers like LGBM showed the best performance in some 5-stage classification tasks37,41, this may be influenced by specific dataset characteristics, and there are concerns about potential data leakage in train-test splitting, as subject-level separation wasn’t always explicitly described38,42. For sleep/wake classification, deep learning models using raw PPG data show the highest accuracies, although they often sacrifice interpretability27,40,51,52.

Despite advancements, several challenges persist in previous studies: limited generalizability due to proprietary datasets, inadequate handling of class imbalance, potential data leakage, and lack of interpretability in deep learning and non-feature-based approaches. The objective of this study is to bridge these gaps by developing an interpretable feature-based machine-learning model using the clinical CAP dataset, with a specific focus on binary epoch-by-epoch sleep-wake classification. Given that many key sleep metrics rely on sleep-wake transitions, binary classification is a practical first step toward robust PPG-based sleep staging. By leveraging a feature-based approach and addressing class imbalance, we aim to create a robust and generalizable model suitable for real-world clinical settings. An overview of the study workflow is presented in Fig. 1.

a Cohort and dataset: 84 participants (33 females, 51 males), with most diagnosed with sleep disorders. 81% of available epochs were sleep, and 19% were wake. b Preprocessing and feature extraction: Steps included signal smoothing with moving average (window size = 10), Chebyshev Type I filtering (0.5–8 Hz, 0.2 dB ripple), normalization, and extraction of 330 features for each epoch (xE). c Feature selection, model training, and evaluation: Feature selection from unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets identified 79 and 35 features, respectively. Random Forest classifier was used for training and evaluation, with confusion matrices showing classification performance for 20-fold cross-validation. d Feature importance: Importance of top features for unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets. e Feature values in wake vs sleep: Distribution comparison of PPG_TM25 feature values, where PPG_TM25 represents the trimmed mean of the PPG signal with 25% of extreme values removed, between wake and sleep stages, showing clear distinction.

Results

Model evaluation

Using the original dataset, the RF classifier demonstrated consistent performance across 5-, 10-, and 20-fold CVs. The optimized hyperparameters for this model included bootstrap set to True, a maximum depth of 19, maximum features set to ‘sqrt’, a minimum of 4 samples per leaf, 2 minimum samples per split, and 500 estimators. The results indicated high overall performance (F1 = 89.05%) and excellent capability in identifying sleep stage (SE = 94.56%) but lower effectiveness in correctly identifying wake stage (SP = 23.85%) (Table 1, Fig. 2). ROC curve analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4) showed that the classifier trained on the unbalanced dataset had moderate discriminative ability (AUC = 0.7104), suggesting limited robustness across different thresholds. Improvements were observed with ADASYN balancing, which maintained high sensitivity (SE = 88.57%) and F1 score (F1 = 81.40%), while significantly enhancing specificity (SP = 71.31%) and MCC (MCC = 0.6080), demonstrating a well-rounded ability to distinguish between sleep and wake stages effectively (Table 1, Fig. 2). This was further supported by ROC curve analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4), where the ADASYN-balanced model achieved an AUC of 0.8798, indicating substantially improved model separability and generalization. The optimized hyperparameters for the classifier trained on the ADASYN-balanced dataset were bootstrap set to False, a maximum depth of 18, ‘sqrt’ for maximum features, a minimum of 1 sample per leaf, 6 minimum samples per split, 367 estimators, and a random state of 42. Confusion matrices for each cross-validation fold using the original and ADASYN-balanced datasets are presented in Fig. 3. To further support the choice of ADASYN over RUS and SMOTE, Supplementary Fig. 5 provides a comparison of classification performance across balancing techniques. While RUS and SMOTE contributed to some improvements in specificity, ADASYN achieved the best balance between sensitivity and specificity, ultimately leading to the highest MCC.

a Classification results: Bar plots comparing the results for sleep-wake classification using 20-fold cross-validation across unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets. The model trained on the unbalanced dataset showed higher ACC, SE, and F1 scores but suffered from significantly lower SP and MCC. In contrast, the ADASYN-balanced model notably enhanced SP and MCC, while also maintaining competitive ACC, SE, and F1 scores. b Comparison of models: A chart visualizing the differences in evaluation metrics between models trained on unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets. ACC accuracy, ADASYN Adaptive Synthetic, CV cross-validation, F1 F1 score, MCC Matthew’s correlation coefficient, No balanc. no balancing (the unbalanced dataset), SE sensitivity, SP specificity. Epoch counts: No balancing: 85,542 (Wake: 16,128, Sleep: 69,414), ADASYN: 139,410 (Wake: 69,754, Sleep: 69,656).

Classification performance varied across sleep disorder groups, with evaluation using LOSO CV revealing distinct patterns in model performance. In the unbalanced dataset, the highest performance was observed in the NFLE and no pathology (No path.) groups, achieving F1 scores of 93.24% and 92.72%, respectively. The narcolepsy (NL) group also performed well, with an F1 score of 92.72%. In contrast, insomnia (INS) had the lowest F1 (68.19%), highlighting its classification challenges. While NFLE, NL and no pathology group had high F1 scores, their low specificity suggests a bias toward classifying wake periods as sleep. Other groups, including periodic limb movements (PLM), REM behavior disorder (RBD), and sleep disordered breathing (SDB), showed moderate performance, with varying trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity. In the ADASYN-balanced dataset, classification improved, particularly in terms of specificity. The classification performance remained the highest in NL (F1 = 87.92%), NFLE (F1 = 82.45%) and no pathology groups (F1 = 81.54%), confirming their reliable classification. INS and SDB showed the lowest performance (F1 = 68.79%, and F1 = 76.95%, respectively), indicating that distinguishing sleep and wake states in these groups remained challenging. Overall, class balancing enhanced classification robustness across sleep disorder groups, particularly improving wake detection, though some conditions, particularly insomnia, remained more challenging (Table 2).

Feature importance

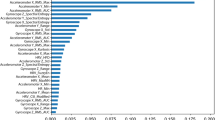

In the sleep-wake classification using the unbalanced dataset, the most important features across all participants included the skewness of the PPG signal (PPG_skew), trimmed mean (PPG_TM25), Lyapunov exponent (PPG_LC), the standard deviation of the ratio between e and a points in the 2nd derivative of the PPG data (e_a_ratio_std), and the RMS of PPI signal (PPI_RMS) (Fig. 4 1a). In the ADASYN-balanced dataset, the most important features included PPI frequency-domain features (PPI_LF_HF_power, _VLF_LF_power, PPI_LF_Total_power, PPI_VLF_HF_power), emphasizing the role of autonomic nervous system activity in differentiating between wake and sleep stages. While PPG morphology and 2nd derivative features (e.g., rise times, width metrics, e/a ratio) remained relevant, their rankings dropped in favor of HRV-based spectral features (Fig. 4 2a). Feature importance patterns also varied between the two most common sleep disorders, RBD and NFLE. A key distinction in RBD was the presence of EMD-Hilbert features, which appeared in the top 20 for both unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets but were absent in NFLE (Fig. 4 1c and 2c) Additionally, while PPG_LC was among the most important features in datasets trained on all participants and RBD patients, it did not appear in the top 20 for NFLE (Fig. 4 1b and 2b). The extent of overlapping and distinct feature importance patterns is further emphasized when examining the overlap among the top features across unbalanced, ADASYN-balanced, and disorder-specific datasets. Several features, such as e_a_ratio_mean, Width_10_Percent_Time_avg, PPI_Min, PPG_Skew, and PPG_TM25, consistently appeared across datasets (Fig. 5a), indicating their broad relevance in sleep-wake classification. However, when focusing on the top 5 features, greater variability emerges, for instance, only PPG_Skew remained consistently among the top 5 features across unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets (Fig. 5b). The distribution of feature groups further highlights these differences (Supplementary Fig. 6). PPG signal characteristic and nonlinear dynamics features were well represented across all groups, reinforcing their overall importance in sleep-wake classification. However, PPI frequency-domain features became more dominant in ADASYN-balanced datasets. These findings suggest that while a core set of features remains important across conditions, the most highly ranked features can shift depending on sleep disorder and balancing approach.

(1) Unbalanced dataset: PPG time-domain and nonlinear dynamics features (e.g., PPG_skew, PPG_TM25, PPG_LC) and time-domain PPI characteristics (e.g., PPI_RMS, PPI_SVD) were among the most influential. (2) ADASYN-balanced dataset: Frequency-domain PPI metrics (e.g., PPI_LF_HF_power, PPI_VLF_LF_power) became more dominant, suggesting their increased role in distinguishing wake from sleep after balancing. For both (1) and (2), (a) shows the top 20 features for all participants, (b) for NFLE patients, and (c) for RBD patients. NFLE nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, RBD REM behavior disorder.

a Top 20 features across different dataset configurations: showing substantial overlap in feature selection across groups. b Top 5 features across datasets: highlights greater variability in the most critical predictors depending on dataset composition and sleep disorder type. Yellow indicates that a feature was included in the top-ranked features for a given dataset, while purple indicates that it was not. While some features, such as PPG_skew and PPG_TM25, were consistently among the top-performing features in all unbalanced datasets, and PPI frequency-domain features in all ADASYN-balanced datasets, the highest-ranked features differed more substantially between NFLE and RBD patients. This suggests that dataset composition and disorder-specific physiological influences impact feature importance.

The role of the most important features in distinguishing wake and sleep states becomes more apparent when examining their distributions. Histograms and boxplots provide a clearer view of how these features separate the two states, highlighting differences in their mean values between wake and sleep classes (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 7). For example, PPG_TM25 and PPG_LC are higher during wake, while PPI_Min shows higher values during sleep. The histograms from ADASYN-balanced dataset show a more apparent distinction between sleep and wake feature values compared to the unbalanced dataset, resulting in less overlap and more defined separation. This improved feature differentiation likely contributes to the improved model performance in detecting the wake stage when using ADASYN-balanced dataset.

Each subplot includes histograms and boxplots illustrating the distribution of values across sleep and wake classes, with corresponding p-values indicating significant group differences. 1 Unbalanced dataset: 1a–1d show results from the unbalanced dataset: 1a PPG_skew, representing the skewness of the PPG waveform; 1b PPG_TM25, the trimmed mean of the PPG signal with 25% of extreme values removed; 1c PPG_LC, the Lyapunov coefficient capturing signal complexity; and 1d e_a_ratio_std, the standard deviation of the ratio between the ‘e’ and ‘a’ points in the second derivative of the PPG waveform. 2 ADASYN-balanced dataset: 2a–2d present results from the ADASYN-balanced dataset, displaying features derived from the frequency-domain analysis of the peak-to-peak interval (PPI) time series. 2a PPI_LF_HF_power, the ratio of low-frequency (LF) to high-frequency (HF) power; 2b PPI_VLF_LF_power, the ratio of very low-frequency (VLF) to LF power; 2c PPI_VLF_HF_power, the ratio of VLF to HF power; 2d PPI_LF_Total_power, the proportion of LF power relative to the total power spectrum.

Discussion

The developed 2-stage classifier for PPG-based sleep staging exhibits competitive performance and overcomes several critical limitations noted in previous research (Table 3). Employing a substantial dataset of 84 participants from the publicly accessible CAP database, we enhance the generalizability of our results. Additionally, we prevented data leakage by employing group-wise cross-validation, ensuring that all data from a given subject are contained within either the training or validation set, effectively avoiding the overlap that can inflate performance metrics. Our study utilizes a feature-based random forest classifier, favoring transparency and interpretability crucial for clinical applications. We also addressed class imbalance, a common issue in sleep staging. While RUS and SMOTE are commonly used for this purpose, they come with inherent limitations - RUS reduces generalizability by eliminating majority class instances, while SMOTE may lead to overfitting and noise by creating new samples. In contrast, ADASYN enhances model robustness by adaptively generating synthetic samples in regions where the class imbalance is more pronounced, and learning is more challenging, thereby enhancing model robustness and improving generalization. We evaluated our classifier on both, the unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of our model’s performance with 16 prior studies on PPG-based sleep-wake classification. However, differences in dataset size, preprocessing, class balancing methods, validation approaches, and model architectures must be considered when interpreting cross-study comparisons. Our developed model achieved an accuracy of 81.15% on the unbalanced dataset and 79.97% on the ADASYN-balanced dataset. Although these figures are slightly lower than those reported in some previous studies36,50,51,55,56,57,59,60 it is crucial to note that these studies often had smaller sample sizes (e.g. n = 255,56, n = 1050,51,60) and potential data leakage issues where the same subjects’ data were possibly included in both training and testing sets50,60. Additionally, two studies with higher accuracies used deep learning approaches with PPG signal as direct inputs51,59, which, while effective, lack the transparency and interpretability provided by the feature-based approach of our model.

While accuracy is a commonly used metric for model evaluation, it may not always provide the most reliable insights for unbalanced datasets. However, previous studies did not consistently report the F1 score and MCC, which better account for class imbalance. Our model on the unbalanced dataset achieved an F1 score of 89.05%, outperforming all but two other studies that provided F1 scores. One study with a higher F1 score (89.47%) only used sleep recordings from two participants51. The other study, which reported an even higher F1 score (94.01%), used recordings from only 10 participants and employed a deep learning approach with the PPG signal as input, rather than a feature-based approach51. The ADASYN-balanced model also showed robust results with an F1 of 81.40% and MCC of 0.61, indicating a balanced classification capability, superior or comparable to most other studies.

Our model demonstrated high sensitivity, indicating its excellence in detecting sleep, with the classifier trained on the unbalanced dataset achieving a rate of 94.47%. This result outperformed most other studies except two47,60. The sensitivity for the ADASYN-balanced model was slightly lower at 88.57%.

Regarding specificity or the model’s ability to detect wake stages, our classifier trained on the unbalanced dataset encountered challenges, marking the lowest specificity among all studies reviewed. Similar difficulties were observed in the study by Eyal et al.57, where there was a substantial gap between high sensitivity (91.70%) and low specificity (38.10%). By employing ADASYN-balancing, we significantly enhanced specificity to 71.31%.

Classification performance varied across sleep disorders, reflecting differences in sleep-wake patterns. Disorders with distinct physiological transitions, such as narcolepsy and nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, exhibited the highest classification efficiency, reflected by the highest F1 scores and MCC values, while conditions with fragmented sleep, such as insomnia and sleep disordered breathing, posed greater challenges. The poor classification performance in insomnia likely stems from frequent micro-arousals and fragmented sleep structure, leading to systematic misclassification of wake as sleep. The classifier’s strong performance in the no-pathology group highlights its effectiveness when applied to stable sleep patterns but also underscores its limitations in detecting subtle sleep-wake transitions in more complex cases.

The feature importance analysis provided valuable insights into the most influential features for sleep-wake classification and the impact of using unbalanced versus ADASYN-balanced dataset. Some features appeared important in both, the unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets, and were supported by previous studies. For example, two features that have been highlighted in multiple prior studies, the trimmed mean of the PPG signal (PPG_TM25)48,49,50,58,60 and the skewness of the PPG signal, indicating the asymmetry of the PPG waveform (PPG_skew)37,48,49,50,54,58,60, were found important in both datasets, likely due to their ability to reflect subtle physiological changes during wakefulness. PPI_min, which reflects the lowest HRV in an epoch and provides insights into cardiovascular stability and sympathetic tone, also consistently appeared among the top-performing features, mirroring findings from previous studies31,58,60. The recurring importance of these features across different methodologies and supported by previous applications in research, underscores their potential to enhance the accuracy of wake detection in PPG-based sleep staging algorithms. On the other hand, some features that appeared important in both datasets were either novel or had limited prior reporting. The Lyapunov coefficient (PPG_LC), which measures the complexity of the PPG signal, was previously reported in only one study50. The mean and standard deviation of the ratio of second derivatives of the PPG signal at ‘e’ and ‘a’ points (e_a_ratio_mean, e_a_ratio_std) also emerged as novel metrics, capturing fluctuations in blood volume during cardiac cycles. To the best of our knowledge, these second derivative features have not been previously reported in PPG-based sleep staging literature. These novel features could significantly enhance the performance and robustness of PPG-based sleep staging classifiers. Whereas the unbalanced dataset relied more on statistical descriptors and PPG waveform morphology, the use of the ADASYN-balanced dataset shifted feature importance toward PPI frequency-domain features such as VLF/LF (used in58,60), VLF/HF (used in58,60), and LF/HF power ratios (extensively utilized in previous studies31,39,46,53,54,58,60), emphasizing the role of autonomic nervous system activity in differentiating between wake and sleep stages. These findings suggest that synthetic resampling alters the importance of certain features, likely due to improved class balance and reduced bias toward dominant sleep states. Additionally, to address whether different sleep disorders emphasize different feature sets, we conducted exploratory analyses on NFLE- and RBD-specific datasets. The results revealed disorder-specific variations in feature selection, especially in terms of feature importance rankings. These differences may reflect distinct autonomic and cardiovascular regulation patterns in NFLE and RBD. Overall, while a core set of features remained relevant across datasets, the most critical predictors varied based on dataset composition and disorder-specific characteristics. This feature importance analysis underscores the value of comprehensive feature engineering and advanced balancing techniques in optimizing sleep staging models. Moreover, the observed differences between NFLE and RBD subjects suggest that further studies could explore disorder-specific feature selection strategies to optimize classification performance in clinical populations.

This study presents a comprehensive exploration of PPG-based sleep staging and feature importance, but several limitations must be acknowledged. Initial model selection lacked prior feature selection and hyperparameter tuning. Ideally, all models in the model selection phase should undergo hyperparameter tuning before and after feature selection to optimize performance. Noise reduction was handled by filtering and excluding epochs with missing peaks or railing, but more robust methods like eliminating epochs based on a signal quality index or excluding subjects with noisy recordings could further enhance data quality. However, excessive noise filtering might limit the model’s applicability to real-world, often noisy, wearable data. Notably, some traditional HRV metrics did not perform well, possibly due to the initial significance and correlation analysis phase. Future research should implement more advanced feature selection methods like Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation, and noise reduction methods to improve model robustness. Additionally, balancing the training set while maintaining an untouched test set would further validate the model’s effectiveness in real-world applications.

The study focused on epoch-by-epoch binary sleep-wake classification due to its computational efficiency and lower susceptibility to class imbalance. Since many key sleep metrics (e.g., total sleep time, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency) primarily depend on distinguishing wake from sleep, this approach remains a practical choice for applications like sleep disorder screening. While the focus of this study was on granular detection of wake and sleep states, future studies could extend this work by evaluating how well epoch-based classification generalizes to summary sleep metrics. In contrast, multi-class sleep staging (e.g., Wake/REM/NREM or finer distinctions) presents additional challenges, including exacerbated class imbalance, particularly for underrepresented stages such as N1 and REM, and increased model complexity. Expanding the classifier to multi-class sleep staging could provide deeper insights into sleep structure. This would require additional physiological inputs, such as actigraphy and skin temperature, and a more balanced dataset to improve classification reliability. Finally, while this study demonstrates the feasibility of PPG-based sleep staging, adapting the model for wearable use remains a challenge due to lower sampling rates, missing data, and computational constraints. Optimizing the model for real-time processing and robust data handling will be key to ensuring its practical application in wearable settings.

The development of an interpretable, feature-based classifier holds significant promise in clinical applications. Such a model not only aids in understanding the physiological underpinnings of sleep and wake stages but also offers transparency in predictions which is crucial for its clinical adoption. Integrating this classifier in wearable technology could revolutionize home-based sleep studies, enabling continuous, non-invasive, patient-friendly, and cost-effective monitoring. Such advancements could facilitate the early detection and management of sleep disorders, potentially before clinical symptoms emerge. Future research should focus on optimizing the model for wearable applications, while also validating it in a broader population with more healthy individuals to enhance its generalizability. Furthermore, expanding the model’s capabilities to classify multiple sleep stages and detect specific sleep disorders could further enhance its clinical utility.

Methods

Dataset

The CAP sleep database62,63, a publicly available clinical dataset operating under the ODC-BY 1.0 license, was used for training the classifier. The dataset includes full overnight polysomnographic (PSG) recordings, from which expert neurologists annotated sleep stages according to the Rechtschaffen and Kales (R&K) rules64. R&K scoring manual categorizes sleep into stages labeled 0 to 5: 0 represents wakefulness, while stages 1 through 5 correspond to sleep stages S1, S2, S3, S4, and REM, respectively. To align with the more recent AASM guidelines10, S3 and S4 can be merged into a single deep sleep stage, N3, with the other stages remaining as is. Out of the 108 available recordings, 84 included raw PPG signals, making them suitable for this study. The PPG signals were collected simultaneously with the PSG recordings, using the same clinical-grade PSG systems. The PPG signal was sampled at 128 Hz and recorded throughout the PSG session. The participant demographics showed a gender distribution of 33 females and 51 males. The average age was 46, with a standard deviation of 20 years. Most participants were diagnosed with sleep disorders, except for four healthy participants. A detailed breakdown of the dataset, including demographics and sleep statistics for each diagnostic group, is provided in Table 4. The PSG-derived labels were used to evaluate the sleep staging classifier trained on PPG-derived features.

Preprocessing

In the preprocessing phase, the initial visual inspection identified three inverted recordings that were subsequently corrected. Next, the PPG data was aligned with the corresponding PSG labels and segmented into 30-second epochs for analysis. The dataset annotations were simplified by consolidating all sleep stages (1-5) into a single ‘sleep’ category, resulting in a binary classification of wake versus sleep.

The signal was smoothed with a 10-point moving average, filtered using a 4th-order Chebyshev Type I bandpass filter (0.5–8 Hz, 0.2 dB ripple), and standardized using z-score normalization. Peaks and onsets were detected using the MSPTD algorithm from the PPG Beats toolbox65. Epochs lacking clear peaks or onsets were discarded. Additionally, epochs exhibiting ‘railing’—defined as having at least three peaks within 20 data points – were removed due to physiological implausibility. A, b and e points were detected from the second derivative of the PPG signal. Peak-to-peak interval (PPI) time series was derived from the PPG signal by converting the intervals between successive peaks to milliseconds. PPIs outside the physiological range (shorter than 330 ms or longer than 1500 ms, corresponding to heart rates above 182 bpm or below 40 bpm, respectively) were excluded. After completing the preprocessing steps, 85,542 epochs were available for training the classifier. The dataset exhibited significant class imbalance, with only 16,128 epochs categorized as ‘Wake’.

Class imbalance

To overcome the inherent class imbalance in sleep stages, adaptive synthetic (ADASYN) oversampling was implemented. ADASYN was chosen over other common methods, such as Random Under Sampling (RUS) and the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), due to RUS’s significant information loss and reduced generalizability and SMOTE’s potential to introduce noise and overfitting. ADASYN adaptively generates synthetic samples based on the dataset’s distribution, reducing bias towards the majority class and enhancing the model’s overall performance and generalizability.

Feature extraction

A comprehensive set of 330 features was extracted using the filtered PPG signal, detected physiological points, and PPI time series. 209 features were derived from the PPG signal and 121 from the PPI time series. These features, derived from literature, enable the development of feature-based machine learning models for accurate sleep stage classification. The full list of extracted features, along with their mathematical definitions and descriptions, is provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The feature extraction process was implemented in Matlab, and the corresponding code is publicly available on Zenodo66.

PPG features

PPG signal characteristic features were derived from the PPG signal to capture the shape and structural properties of the waveform in one PPG cycle, such as systolic peaks, systolic and diastolic areas, cycle duration, and the width between specific amplitude points (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for the key pulse wave characteristics used for feature extraction). Additionally, the second derivative of the PPG signal, which highlights the rate of change in the signal’s slope, was used to derive features related to the a, b, and e points. These features capture subtle changes in the waveform that may correlate with physiological phenomena occurring during different sleep stages, such as changes in the cardiac rhythm regularity and blood flow dynamics.

Time-domain features provided insights into the PPG signal’s amplitude variations and other statistical characteristics. Features such as minimum, maximum, and range; central tendency measures like the mean, median, and trimmed means; and various variability measures were included. These features help assess the stability and irregularities in the PPG signal, which may vary across different sleep stages.

Frequency-domain features were extracted using both Welch’s method and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) approaches to analyze the power spectral density (PSD) across various frequency bands. The selection of specific frequency bands and analytical methods was guided by the work presented by Wu et al. (2020)39, Olsen et al. (2023)61, and Uçar et al. (2018)58. Power spectral density was analyzed across 0–1.25 Hz, 1.25–2.5 Hz, 2.5–5 Hz, 5–10 Hz, and 10–20 Hz, providing insights into signal energy distribution. Total power and variability across these bands were also assessed, reflecting overall signal strength and fluctuations. FFT calculations extended to VLF (0.0033 to 0.04 Hz), LF (0.04–0.15 Hz), and HF (0.15–0.4 Hz) bands, revealing slow oscillatory processes and providing insights into autonomic functions. Additionally, energy measures and ratios within LF (0.04–0.15 Hz), MF (0.09–0.15 Hz), and HF (0.15–0.6 Hz) bands were quantified. While FFT is common for spectral estimation, it assumes signal stationarity and suffers from spectral leakage, especially in non-stationary PPG signals. Welch’s method mitigates this by applying overlapping windows, Hanning windowing, and averaging periodograms, improving frequency resolution and reducing leakage.

Nonlinear dynamics features were extracted to capture the complex and irregular behaviors of the PPG signal that are not apparent through linear analysis alone. These features include energy measures such as average and Teager energy, statistical metrics like skewness and kurtosis, and Hjorth parameters that reflect the signal’s variance, frequency, and change rate. Poincaré plot analysis provided insights into signal variability, while fractal dimensions and recurrence analysis assessed the signal’s fractal geometry and pattern predictability. Entropy metrics were used to measure the signal’s unpredictability.

The empirical mode decomposition (EMD)-Hilbert analysis was employed to decompose the PPG signal into its first intrinsic mode function (IMF), allowing for the extraction of features related to the amplitude, frequency, and phase.

Discrete wavelet transform (DWT) utilized the ‘sym6’ wavelet for its resemblance to PPG waveforms, providing a multi-resolution analysis that integrates both time- and frequency-domain data. A five-level wavelet decomposition extracted key features such as energy, variance, mean, and standard deviation from each level and the approximate coefficients.

PPI features

Time-domain features were extracted from the PPI time series to quantify heart rate variability (HRV), a key indicator of autonomic nervous system activity during sleep. In addition to standard statistical metrics similar to those used in PPG analysis, HRV-specific measures such as the standard deviation of PPI (SDNN), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and counts of significant interval differences (NN50, NN20) were also derived.

Frequency-domain features. Using Welch’s method, power spectral density was calculated for VLF (0–0.04 Hz), LF (0.04–0.15 Hz), and HF (0.15–0.4 Hz) bands. Each band’s power, logarithmic power transformation, peak frequency, total power across all bands and various power ratios were calculated. Welch’s method was chosen over FFT because it provides a more reliable spectral estimate for non-stationary signals, where transient fluctuations in autonomic activity may be lost in standard FFT processing. Frequency-domain features derived from the PPI time series provide critical insights into the autonomic nervous system’s behavior during sleep. For instance, VLF power can indicate thermoregulation (elevated during REM), LF sympathetic (elevated during REM) and HF parasympathetic activity (elevated during NREM)67.

Non-linear dynamics features extracted from the PPI time series include those analogous to PPG. Additionally, Teager energy features were computed for the PPI signal’s first IMF, derived using EMD and Hilbert Transform. Additionally, visibility graph analysis was conducted to explore the interconnected patterns of heartbeats, offering insights into the heart rate complexity and its implications for sleep-wake classification.

Feature selection

For the feature selection process, first, a systematic evaluation was conducted to select features that significantly differed between sleep and wake stages. Initially, each feature underwent a normality test using the Shapiro-Wilk method68 to determine the appropriate statistical test for further analysis. Then, features that passed the normality test were analyzed using t-tests, while those that did not were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test69. Significance analysis revealed 266 features that significantly differed between wake and sleep. To further refine feature selection and address multicollinearity, groups of features with correlation coefficients above 0.95 were identified as redundant. Only one feature was selected from each group, reducing overfitting and enhancing computational efficiency. 74 features were removed due to high correlations (n = 71) or feature calculations resulting in missing values (n = 3). The SelectFromModel framework was then used to further minimize dimensionality by retaining only the most impactful features. This method employed a Random Forest model to assign importance scores to each feature. Features below a certain importance threshold were discarded, enhancing the model’s robustness. For the unbalanced dataset, 75 final features were selected for model training, primarily PPG signal characteristics and time-domain features, while DWT and PPI-derived features were largely excluded (Table 5). For ADASYN-balanced dataset, only 35 features were selected. These features similarly included many PPG signal characteristics, but also included more PPI frequency-domain and nonlinear dynamics features (Table 6). Selected features predominantly captured slow-wave cardiovascular dynamics, including cycle duration, peak amplitude, and systolic/diastolic areas, which can reflect sleep-wake transitions. In contrast, high-frequency PSD, wavelet decomposition, and entropy-based nonlinear features were mostly discarded, suggesting that transient signal fluctuations and complexity-based measures were less relevant for classification. To examine whether feature importance varied across sleep disorders, we conducted additional SelectFromModel analyses on datasets including the two most common groups: nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE) with 39 patients and REM behavior disorder (RBD) with 18 patients. Feature selection patterns not only differed between unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets but also varied across sleep disorders, highlighting how dataset composition and disorder-specific characteristics influence feature importance (see Supplementary Figures 2 and 3 and Supplementary Table 3 for a detailed breakdown). Feature importances were then assessed to determine the influence of each feature on the model’s performance. After training the models, feature importances were derived directly from the scikit-learn feature_importances_ attribute of the classifiers.

Model selection

The models used in PPG-based sleep staging in previous research vary, ranging from traditional machine learning algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM)38,48,49,50,53,58, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)48,50,56,58, Random Forest (RF)50, Linear Discrimnant Analysis (LDA)32,43,44, Bayesian classifiers55,57 and Light Gradient Boosted Machine (LGBM)37,47 to advanced deep learning techniques such as Conventional33, Convolutional (CNNs)34,51,59, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs)31,33,35,36,45,52, Deep (DNNs)27,42,61 and Articificial Neural Networks (ANNs)39, and hybrid models like CNN-RNN30,40,41 and CNN-SVM28. To ensure model interpretability, a range of traditional machine learning techniques were evaluated using Python’s sklearn library, including RF, LGBM, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), as well as ensemble combinations (LGBM + XGBoost, RF + LGBM, and RF + XGBoost). For initial model selection, we performed 5-fold GroupKFold cross-validation (CV), ensuring that training and testing sets remained subject-independent. This evaluation was conducted without hyperparameter tuning, using only non-correlated significant features to identify the best-performing model. RF outperformed other classifiers in terms of accuracy and F1 score (Supplementary Table 4), and was selected for further analysis due to its robustness and ability to provide detailed insights into feature importance. Subsequently, we trained the RF model separately on the original dataset and the ADASYN-balanced dataset, validating performance using 5-, 10-, and 20-fold GroupKFold CV, as well as Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) CV to assess variability across groups. Additionally, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test to evaluate statistical differences between groups for key classification metrics, and if significant, performed post-hoc Mann-Whitney U tests to identify specific group differences.

Hyperparameter tuning

The performance of Random Forest classifier was optimized through a hyperparameter tuning process using the Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC) as the scoring metric. MCC was selected due to its robustness to class imbalance, which is inherent in sleep-wake classification, where sleep epochs outnumber wake epochs. A default 0.5 threshold was used for classification. First, Randomized Search was conducted to explore a wide range of hyperparameters, including n_estimators (100–500), max_depth (None, 3–20), min_samples_split (2–11), min_samples_leaf (1–11), max_features (None, ‘sqrt’, ‘log2’) and bootstrap (True, False). Using 3-fold GroupKFold cross-validation, 100 different combinations were assessed. Subsequently, Grid Search was employed to fine-tune the hyperparameters around the best values identified from the initial search, and 3-fold GroupKFold cross-validation was used to ensure consistency. Hyperparameter tuning was performed separately on the unbalanced and ADASYN-balanced datasets.

Model evaluation

A comprehensive set of metrics, namely accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and F1 Score, were utilized to assess the classifier’s performance on an epoch-by-epoch basis, where evaluation metrics were calculated using counts of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN). The receiver operating characteristic - area under the curve (ROC AUC) was used to evaluate the model’s ability to distinguish between sleep and wake across varying classification thresholds, with values closer to 1 indicating better performance and values near 0.5 suggesting random classification. Additionally, the MCC was employed for its robustness in imbalanced datasets70,71. Confusion matrices were calculated to further illustrate the performance across wake and sleep stages.

Accuracy (ACC)

Sensitivity (SE, true positive rate)

Specificity (SP, true negative rate)

F1 score

where

and

Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC)

Receiver operating characteristic -area under the curve (ROC AUC)

Data availability

The data used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed through the CAP Sleep Database on PhysioNet (https://physionet.org/content/capslpdb/1.0.0/)62.

Code availability

The code described in this manuscript is publicly accessible on GitHub at https://github.com/karmenmarkov/An-Interpretable-Feature-Based-Machine-Learning-Approach-for-Automatic-Sleep-Staging-Using-PPG. In addition, the specific version of the code discussed in the paper has been archived and is available via a DOI-minting repository, Zenodo66.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults — United States. Mmwr. Morbidity Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 137–141 (2016).

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 687–698 (2019).

Grandner, M. A. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep. Med. Clin. 17, 117–139 (2022).

Bonnet, M. & Arand, D. 24-hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep 18 7, 581–8 (1995).

Wei, Y. et al. Sleep stage transition dynamics reveal specific stage 2 vulnerability in insomnia. Sleep 40, zsx117 (2017).

Hermans, L. W. A. et al. Sleep-wake survival dynamics in people with insomnia. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 13, 349–360 (2021).

Ng, A. K. & Guan, C. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on sleep-wake stage ratio. In 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 4660–4663 (IEEE, 2012).

Ferri, R. et al. Increased electroencephalographic high frequencies during the sleep onset period in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep 37 8, 1375–81 (2014).

Geng, C., Yang, Z., Zhang, T., Xu, P. & Zhang, H. Polysomnographic nighttime features of restless legssyndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurology 13, 961136 (2022).

Berry, R. et al. The aasm manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: Rules, terminology and technical specifications, version 2.2. Darien, Ill.: Am. Acad. Sleep. Med., 2015 11, 1253–1254 (2015).

Rosenberg, R. S. & Van Hout, S. The american academy of sleep medicine inter-scorer reliability program: sleep stage scoring. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 09, 81–87 (2013).

Levendowski, D. J. et al. The accuracy, night-to-night variability, and stability of frontopolar sleep electroencephalography biomarkers. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 13, 791–803 (2017).

Chouraki, A., Tournant, J., Arnal, P., P‚pin, J.-L. & Bailly, S. Objective multi-night sleep monitoring at home: variability of sleep parameters between nights and implications for the reliability of sleep assessment in clinical trials. Sleep 46, zsac319 (2023).

Ancoli-Israel, S. et al. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep 26, 342–392 (2003).

Smith, M. et al. Use of actigraphy for the evaluation of sleep disorders and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders: an american academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 14, 1231–1237 (2018).

Cole, R. J., Kripke, D. F., Gruen, W., Mullaney, D. J. & Gillin, J. C. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep 15, 461–469 (1992).

Marino, M. et al. Measuring sleep: accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of wrist actigraphy compared to polysomnography. Sleep 36, 1747–1755 (2013).

de Souza, L. et al. Further validation of actigraphy for sleep studies. Sleep 26, 81–85 (2003).

Blood, M., Sack, R., Percy, D. & Pen, J. A comparison of sleep detection by wrist actigraphy, behavioral response, and polysomnography. Sleep 20, 388–395 (1997).

Paquet, J., Kawinska, A. & Carrier, J. Wake detection capacity of actigraphy during sleep. Sleep 30, 1362–1369 (2007).

Birrer, V., Elgendi, M., Lambercy, O. & Menon, C. Evaluating reliability in wearable devices for sleepstaging. npj Digital Medicine 7, 74 (2024).

Penzel, T., Kantelhardt, J., Grote, L., Peter, J. & Bunde, A. Comparison of detrended fluctuation analysis and spectral analysis for heart rate variability in sleep and sleep apnea. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 50, 1143–1151 (2003).

Elsenbruch, S., Harnish, M. & Orr, W. Heart rate variability during waking and sleep in healthy males and females. Sleep 22, 1067–1071 (1999).

Allen, J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol. Meas. 28, R1–R39 (2007).

Almarshad, M. A., Islam, M. S., Al-Ahmadi, S. & Bahammam, A. S. Diagnostic features and potential applications of ppg signal in healthcare: A systematic review. Healthcare 10, 547 (2022).

Phan, K. D., Luu, T. T. & Huynh, D. A. Ppg signal and application in themedical field. VNUHCM J of Eng. & Technol. 6, 1826–1843 (2023).

Kotzen, K. et al. Sleepppg-net: A deep learning algorithm for robust sleep staging from continuous photoplethysmography. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 924–932 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Transfer learning from ecg to ppg for improved sleep staging from wrist-worn wearables. Physiol. Meas. 42, 045002 (2021).

Cakmak, A. et al. An unbiased, efficient sleep-wake detection algorithm for a population with sleep disorders: Change point decoder. Sleep 43, zsaa011 (2020).

Vaquerizo-Villar, F. et al. Automatic sleep staging in children with sleep apnea using photoplethysmography and convolutional neural networks. In 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 216–219 (2021).

Radha, M. et al. A deep transfer learning approach for wearable sleep stage classification with photoplethysmography. npj Digital Med. 4, 1–11 (2021).

Fonseca, P. et al. Validation of photoplethysmography-based sleep staging compared with polysomnography in healthy middle-aged adults. Sleep 40, zsx097 (2017).

Van Meulen, F. et al. Contactless camera-based sleep staging: The healthbed study. Bioengineering 10, 1 (2023).

Fonseca, P. et al. A computationally efficient algorithm for wearable sleep staging in clinical populations. Sci. Rep. 13 (2023).

Wulterkens, B. et al. It is all in the wrist: Wearable sleep staging in a clinical population versus reference polysomnography. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 13, 885–897 (2021).

Gilst, M. et al. Direct application of an ecg-based sleep staging algorithm on reflective photoplethysmography data decreases performance. BMC Res. Notes 13, 513 (2020).

Zhao, X. & Sun, G. A multi-class automatic sleep staging method based on photoplethysmography signals. Entropy 23, 116 (2021).

Molkkari, M. et al. Non-linear heart rate variability measures in sleep stage analysis with photoplethysmography. In 2019 Computing in Cardiology (CinC), Page 1–Page 4 (2019).

Wu, X., Yang, J., Pan, Y., Zhang, X. & Luo, Y. Automatic sleep-stage scoring based on photoplethysmographic signals. Physiol. Meas. 41, 065008 (2020).

Korkalainen, H. et al. Deep learning enables sleep staging from photoplethysmogram for patients with suspected sleep apnea. Sleep 43, zsaa098 (2020).

Huttunen, R. et al. Assessment of obstructive sleep apnea-related sleep fragmentation utilizing deep learning-based sleep staging from photoplethysmography. Sleep 44 (2021).

Huttunen, R. et al. A comparison of signal combinations for deep learning-based simultaneous sleep staging and respiratory event detection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 1704–1714 (2023).

Beattie, Z. et al. Estimation of sleep stages in a healthy adult population from optical plethysmography and accelerometer signals. Physiological Meas. 38, 1968 (2017).

Fedorin, I., Slyusarenko, K., Lee, W. & Sakhnenko, N. Sleep stages classification in a healthy people based on optical plethysmography and accelerometer signals via wearable devices. In 2019 IEEE 2nd Ukraine Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (UKRCON), 1201–1204 (2019).

Slyusarenko, K., Fedorin, I. & Lee, W. Sleep stages classifier with eliminated apnea impact. In Adjunct Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 210–213 (2019).

He, D., Li, M., Yang, H., Kang, W. & Ou, Y. A joint classifier for sleep staging with pulse rate variability based on automatic weight assignment. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), 1582–1587 (2019).

Altini, M. & Kinnunen, H. The promise of sleep: A multi-sensor approach for accurate sleep stage detection using the oura ring. Sensors 21, 4302 (2021).

Motin, M. A., Karmakar, C. K., Penzel, T. & Palaniswami, M. Sleep-wake classification using statistical features extracted from photoplethysmographic signals. In 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 5564–5567 (2019).

Motin, M. A., Karmakar, C., Palaniswami, M. & Penzel, T. Photoplethysmographic-based automated sleepwakeclassification using a support vector machine. Physiol. Meas. 41, 075013 (2020).

Motin, M. A., Karmakar, C., Palaniswami, M., Penzel, T. & Kumar, D. Multi-stage sleep classification using photoplethysmographic sensor. R. Soc. Open Sci. 10 (2023).

Habib, A. et al. Performance of a convolutional neural network derived from ppg signal in classifying sleep stages. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 1717–1728 (2023).

Topalidis, P. I. et al. From pulses to sleep stages: Towards optimized sleep classification using heart-rate variability. Sensors 23, 9077 (2023).

Dehkordi, P. et al. Sleep stage classification in children using photoplethysmogram pulse rate variability. In Computing in Cardiology 2014, 297–300 (2014).

Dehkordi, P., Garde, A., Dumont, G. A. & Ansermino, J. M. Sleep/wake classification using cardiorespiratory features extracted from photoplethysmogram. In 2016 Computing in Cardiology Conference (CinC), 1021–1024 (2016).

Bozkurt, F., Bozkurt, M. R., Uçar, M. K., Bilgin, C. & Köklükaya, E. Utilizing photophlethysmography signal features and implementing a decision tree to determine sleep cycles-non sleep cycles. In 2016 24th Signal Processing and Communication Application Conference (SIU), 917–920 (2016).

Tuna, S., Bozkurt, M. R., Uçar, M. K. & Bilgin, C. Sleep staging using photoplethysmography signal and knn nearest neighbor algorithm. In 2016 24th Signal Processing and Communication Application Conference (SIU), 1373–1376 (2016).

Eyal, S. & Baharav, A. Sleep insights from the finger tip: How photoplethysmography can help quantify sleep. In 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC), 1–4 (2017).

Ucar, M., Bozkurt, M., Bilgin, C. & Polat, K. Automatic sleep staging in obstructive sleep apnea patients using photoplethysmography, heart rate variability signal and machine learning techniques. Neural Comput. Appl. 29 (2018).

Malik, J., Lo, Y.-L. & Wu, H.-T. Sleep-wake classification via quantifying heart rate variability by convolutional neural network. Physiol. Meas. 39, 085004 (2018).

Bozkurt, M., Ucar, M., Bozkurt, F. & Bilgin, C. Development of hybrid artificial intelligence based automatic sleep/awake detection. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 14, 353–366 (2020).

Olsen, M. et al. A flexible deep learning architecture for temporal sleep stage classification using accelerometry and photoplethysmography. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 228–237 (2023).

Goldberger, A. et al. Physiobank, physiotoolkit, and physionet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 101, e215–e220 (2000).

Terzano, M. G. et al. Atlas, rules, and recording techniques for the scoring of cyclic alternating pattern (cap) in human sleep. Sleep. Med 2, 537–553 (2001).

Rechtschaffen, A. & Kales, A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system of sleep stages in human subjects (Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, University of California, 1968).

Charlton, P. H. et al. Detecting beats in the photoplethysmogram: benchmarking open-source algorithms. Physiol. Meas. 43, 085007 (2022).

Markov, K. & Elgendi, M. An interpretable feature-based machine learning approach for automatic sleep staging using ppg https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13171302 (2024).

Busek, P., Vanková, J., Opavsky, J., Salinger, J. & Nevsimalova, S. Spectral analysis of heart rate variability in sleep. Physiol. Res. 54, 369–376 (2005).

Shapiro, S. S. & Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611 (1965).

Mann, H. B. & Whitney, D. R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 18, 50–60 (1947).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics 21, 6 (2000).

Boughorbel, S., Jarray, F. & El-Anbari, M. Optimal classifier for imbalanced data using matthews correlation coefficient metric. PLoS ONE 12, 1826–1843 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E. designed and led the study. K.M. and M.E. developed the classifier. V.B. provided preliminary work for developing theclassifier. K.M. and M.E. conducted the analysis and the comparison with existing research. C.M. oversaw the entire reviewprocess, including manuscript review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors K.M., M.E., V.B., and C.M. declare no financial or non-financial competing interests. Author M.E. serves as an associate editor of this journal and had no role in the peer-review or decision to publish this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markov, K., Elgendi, M., Birrer, V. et al. Interpretable feature-based machine learning for automatic sleep detection using photoplethysmography. npj Biosensing 2, 24 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00041-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00041-2

This article is cited by

-

A deep learning approach with data augmentation for robust SAHS classification from nasal pressure signals

International Journal of Information Technology (2025)