Abstract

In this study, we report the development of a multiplexed carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistor (FET) sensor platform for the rapid and reliable detection of opioids and their metabolites in human sweat. Our approach utilizes gold nanoparticle-decorated, semiconductor-enriched single-walled carbon nanotubes (Au-SWCNTs) functionalized with specific antibodies to achieve sensitive and selective detection of opioid metabolites to indicate opioid exposure. First, norfentanyl antibody-functionalized FET sensors exhibited high sensitivity toward norfentanyl with a limit of detection of 34 pg/mL (146 pM). To extend the detection capabilities, we constructed a sensor array comprising FET sensors functionalized with antibodies targeting morphine, norfentanyl, and 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM). Notably, the cross-reactivity of the antibodies among structurally similar compounds broadened the detection range of the sensor array, enabling simultaneous probing of both opioid metabolites and their parent drugs. The sensor array was further incorporated into an automated sensing platform, facilitating high-throughput measurements and enhanced data reliability. In addition, the sensor technology was successfully adapted into a portable configuration, underscoring its potential for rapid, reliable opioid screening in real-world settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Opioid use disorder remains a major global health crisis, requiring effective and comprehensive management strategies. Laboratory drug testing plays a crucial role in this effort by providing essential information about a patient’s opioid exposure history1, which is critical for accurate diagnosis, ongoing monitoring, and treatment decisions. Although urine remains the most commonly used biological matrix for drug testing, research works explored drug testing methods in alternative biological samples, including sweat2,3,4, saliva5,6, and hair7,8,9,10. Among these, sweat stands out as a particularly promising option due to its non-invasive collection process and ease of accessibility. More importantly, sweat testing offers the advantage of capturing both acute and prolonged opioid exposure, widening the detection window compared to urine and saliva testing11,12.

Common analytical techniques for detecting opioids and their metabolites in human sweat include liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS)13,14. Both methods are known for their high sensitivity and selectivity, allowing for accurate identification of opioids and their metabolites in complex biological samples. As a result, these techniques are widely regarded as the gold standard for confirmatory drug testing. However, there are limitations associated with these techniques, such as the requirement of specialized equipment and training, making them relatively expensive and time-consuming. Immunoassay-based techniques, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and lateral flow assay (LFA), have also been employed for the screening of drugs of abuse in bodily fluids15,16,17. Relying on ligand-antibody interactions, this technology offers fast and selective detection of target molecules. In general, immunoassays are widely available, cost-effective, and easy to perform, making them suitable for preliminary testing, but they sometimes lack sensitivity and reliability.

Electrochemical sensors detect target analytes at the electrode-electrolyte interface, generating electrical signals that correlate with analyte concentrations. As a result, they offer high sensitivity, rapid response times, and suitability for point-of-care applications18. Additionally, electrochemical sensors are also well known for their compact size, low cost, and user-friendly operation, making them ideal candidates for the screening of opioid drugs and their metabolites in various biological matrices19,20,21,22,23,24.

In this work, single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT)-based field-effect transistor (FET) sensors were utilized to enable the sensitive detection of opioid drugs and their metabolites in sweat samples. Previous research from our group has shown remarkable sensing capabilities of the antibody-functionalized SWCNT-FET sensors for the detection of fentanyl and norfentanyl in calibration samples (1× PBS)25,26. Building upon our previous work, we employed the same sensor configuration, selecting semiconductor (sc)-enriched SWCNTs as the sensing material and decorating sc-SWCNTs with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) for the immobilization of antibodies. The sensing results displayed high sensitivity of the norfentanyl antibody-functionalized FET sensor (NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensor) toward norfentanyl, achieving a limit of detection of 34 pg/mL (146 pM).

Moreover, electrochemical sensors are well-suited for high-throughput analysis due to their compact size, rapid response times, and inherent compatibility with automation systems. In light of the increasing prevalence of fentanyl and its analogs being mixed with other drugs, there is a growing need for multiplexed sensing platforms that provide comprehensive insights into a patient’s opioid exposure history. To address this challenge, we developed a sensor array incorporating SWCNT-FET sensors functionalized with various antibodies, enabling the detection of multiple opioid metabolites as well as their parent drugs in sweat samples. Meanwhile, laboratory automation is essential to facilitate high-throughput sensing experiments, and previous studies have demonstrated the successful integration of electrochemical sensors with automated laboratory workflows27,28,29,30,31. In this work, we integrated a pipetting robot with a sourcemeter and a switching matrix, thereby constructing an automated sensing platform capable of testing up to 96 sensors32. The combination of our sensor array and automated platform not only minimizes human error but also enhances data reliability. Furthermore, our sensor array results indicate that, due to cross-reactivity, the antibody-functionalized FET sensors are capable of detecting both opioid metabolites and their parent drugs; however, different sensitivities were observed due to different binding affinities.

Lastly, we integrated our sensor technology into a portable system by using a FET electrode with source, drain, and gate electrodes on the same plane, eliminating the need for a separate gate electrode. The portable sensing setup also showed good sensing performance for the detection of opioid exposure.

Results and discussion

Sensor fabrication

Figure 1a illustrates a sensor chip packaged in a 40-pin dual-in-line package for FET measurements. The sensor chip, measuring only 2.6 × 2.6 mm, contains eight FET devices, allowing for parallel sensing within a single experiment. Figure 1b–d presents microscopic characterizations of the FET sensor chip at each stage of the fabrication process. Firstly, sc-SWCNTs, which function as the semiconducting channels of the FET sensors, were deposited onto the Si/SiO₂ substrate by dielectrophoresis (DEP). This process resulted in the formation of a dense SWCNT network between the interdigitated gold electrodes, with a channel length of 6 µm (Fig. 1b). The average diameter of the sc-SWCNT bundles on the substrate is 4.0 ± 1.6 nm.

a Top: Optical image of a sensing chip with eight devices. Bottom: The sensing chip was wire-bonded into a 40-pin dual inline package (DIP) for FET measurements. b SEM image (top) and AFM image (bottom) of SWCNTs deposited between the interdigitated electrodes. c SEM image (top) and AFM image (bottom) of AuNPs decorated SWCNTs. d SEM image (top) and AFM image (bottom) of norfentanyl antibody-functionalized Au-SWCNT FET devices.

To ensure robust binding of norfentanyl antibodies (NOR-ab) on the sensing surface, sc-SWCNTs were decorated with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). The AuNPs provided a large surface area, facilitating the spontaneous attachment of antibodies to their surfaces. Via bulk electrolysis, AuNPs preferentially nucleated and grew on the oxygen-containing defects of the SWCNTs33,34. The morphology of AuNP-decorated sc-SWCNTs (Au-SWCNTs) was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which revealed the formation of discrete, round AuNP clusters on the nanotube surface. Additionally, Raman spectroscopy demonstrated an approximately seven-fold enhancement in peak intensity after AuNP decoration (Fig. S1). This amplification was attributed to the surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) effect, further confirming the successful integration of AuNPs onto the SWCNT network.

The integration of norfentanyl antibodies onto the sensor chip was first examined by X‑ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Fig. S2). In the survey spectrum, new peaks that correspond to Au 4f and N 1s emerged after decorating the SWCNTs with AuNPs and incubating them with norfentanyl antibodies. A high‑resolution scan of the N1s further confirmed the appearance of nitrogen, directly evidencing antibody immobilization on the device surface. Deconvolution of the high‑resolution Au4f envelope revealed both Au(0) and Au(I) components, suggesting the formation of Au–S bonds between the gold nanoparticles and thiol groups on the antibodies35,36.

Morphological studies of the antibody-functionalized Au-SWCNTs were carried out using both SEM and atomic force microscopy (AFM). SEM imaging of the sensing surface showed an increase in the size of the AuNPs and the development of rougher surface morphology of the AuNPs, indicating the preferential binding of antibodies to the AuNPs. AFM analysis revealed that the average height of AuNPs before antibody binding was 54.3 ± 12.7 nm. Following incubation with NOR-ab, this height increased to 63.8 ± 13.9 nm. The observed 9.6 nm increase is consistent with the size of an IgG-type antibody, confirming the immobilization of NOR-ab on the FET sensor surface37.

Electrical properties of the NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors during fabrication were studied by recording their FET transfer characteristics (Fig. S3). Id–Vg curve of the bare sc-SWCNT FET device showed typical transfer characteristics of p-type SWCNT FETs. Upon AuNP decoration, higher source-drain current in the p-type region was observed, indicating an increase in the conductivity of the sc-SWCNTs. Following antibody immobilization, the transfer curve displayed a negative shift in threshold voltage, which can be attributed to the introduction of negative charges on the sensing surface by the bound antibodies38.

The stability of the antibody-functionalized sensing surface was assessed by repeatedly exposing the NOR‑ab@Au‑SWCNT FET sensors to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and recording the FET transfer characteristics (Fig. S4a, b). The absence of notable changes across these six cycles confirms that the antibodies remain firmly immobilized and that the sensing surface remained stable throughout the experiments. Signal stability was further evaluated by acquiring 20 consecutive transfer curves in the same gating medium (Fig. S4c, d). The source–drain current at Vg = –0.3 V fluctuated by only around 3% over these measurements, demonstrating excellent electrical stability of the sensor.

Norfentanyl sensing using NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors

When monitoring the source-drain current (Id) over time (I-t scan), a decrease in Id was observed upon introducing sweat samples containing norfentanyl to the FET sensor (Fig. S5a, b). Analysis of the FET characteristics revealed that exposing the sensor chip to sweat samples with increasing concentrations of norfentanyl resulted in a shift in the threshold voltage toward more negative gate voltages (Fig. S5c). By plotting the sensor responses against norfentanyl concentrations, it became evident that both sensing modes produced consistent and comparable sensing results (Fig. S5d).

However, due to the complex composition of artificial sweat, the potential for non-specific binding of various species on the sensing surface cannot be overlooked. Major components in artificial sweat, such as urea and lactic acid39, were previously reported to have interactions with carbon nanotubes40,41. To investigate this effect, blank tests using artificial sweat were conducted to evaluate the sensor’s response to sweat components in the absence of norfentanyl. As shown in Fig. S6, for both sensing modes, the FET sensors showed noticeable responses when being repeatedly exposed to blank sweat samples, suggesting a significant level of non-specific interactions. A comparison of the calibration plots for norfentanyl sensing and blank tests further suggested that a substantial portion of the sensor signal originated from these non-specific interactions between artificial sweat components and the sensing materials. This finding indicates that background interference from sweat must be effectively minimized to accurately evaluate the sensing performance of the NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors. Without proper mitigation of the sweat effect, it becomes challenging to distinguish specific binding of norfentanyl from non-specific interactions, potentially compromising the reliability and sensitivity of the sensor.

To minimize the interference from artificial sweat, a washing step was added to the sensing experiment. The optimized sensing protocol began with a 10-min incubation of the FET sensor with the sample, allowing for specific binding between norfentanyl and the antibodies. This was followed by a thorough washing step using nanopure water to remove non-specifically bound species and excess target molecules from the sensing surface. Finally, FET measurements were conducted with a 1000-fold diluted PBS solution (0.001× PBS) as the gating liquid. The sensor output after implementing the optimized protocol is illustrated in Fig. 2a, where a consistent decrease in source-drain current was observed as norfentanyl concentrations increased. The calibration curve analysis showed that the linear working range of the NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors was from 0.385 pg/mL to 753 pg/mL, and the calibration sensitivity was 0.065 (Figs. 2b and S7). Additionally, the limit of detection (LOD) was determined to be 34 pg/mL (146 pM), highlighting the high sensitivity of the NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors for detecting norfentanyl in sweat samples.

a FET characteristic curves, i.e., source-drain current (Id) versus applied liquid gate voltage (Vg), for norfentanyl sensing using the optimized sensing protocol. The inset shows an illustration of the sensor configuration. b Calibration plot for the detection of norfentanyl using the optimized sensing protocol. The absolute relative responses were calculated by averaging six NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET devices tested in the experiment. The error bars correspond to the standard errors of the averaged absolute relative responses. The concentration of norfentanyl indicated on x-axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale.

A blank test was conducted again using the optimized sensing protocol to further evaluate the effectiveness of mitigating non-specific interference. As illustrated in Fig. S8, the comparison between the calibration curves for norfentanyl sensing and the blank test showed that non-specific interference from artificial sweat remained minimal (relative responses around 0.5%), and the interference did not induce further sensor responses after the third test. This result suggests that the optimized washing step successfully reduced the impact of the sensing medium on sensor response. Furthermore, with the incorporation of the washing step, norfentanyl sensing experiments conducted with samples prepared in 1000-fold diluted artificial sweat (0.001× sweat) produced results comparable to those obtained with undiluted (1×) sweat (Fig. S9). This result not only confirms that the washing procedure minimizes interference from artificial sweat but also demonstrates that sweat samples can be directly applied to the sensor without requiring further processing.

In our previous work, we reported control experiments using Au‑SWCNT FET devices without NOR‑abs, which showed no significant response to norfentanyl25. With sweat interference effectively eliminated in the current study, the observed decrease in source can therefore be attributed solely to the specific binding of norfentanyl to its antibodies. Previous studies have shown that the binding occurred at the binding pocket of the antibody typically involves the formation of hydrogen bonds and cationic-π interactions42,43. Consequently, the sensing mechanism is likely driven by alterations in the charge distribution of the antibody resulting from these interactions, leading to a decrease in the work function of the AuNPs44. This, in turn, increases the Schottky barrier at the junction of the AuNPs and SWCNTs, causing a reduction in the conductance of the FET devices45,46.

Sensor array integrated with an automated sensing platform

While fentanyl is a major contributor to the opioid crisis, other opioids such as codeine, morphine, and heroin also pose significant risks. Detecting a broad range of opioid drugs and their metabolites in human sweat—beyond just norfentanyl—is critical for accurate drug monitoring, forensic analysis, and public health interventions. Hence, based on our previous studies utilizing antibody-functionalized Au-SWCNT FET sensors for the ultrasensitive detection of fentanyl and norfentanyl, we developed a sensor array incorporating FET sensors functionalized with three different antibodies, namely norfentanyl antibody (NOR-ab), morphine antibody (MOR-ab), and 6-monoacetylmorphine antibody (6-MAM-ab).

Apart from the specific target of the three antibodies (NOR, MOR, and 6-MAM), the sensor array can be expanded to detect the corresponding parent drugs, i.e., fentanyl, codeine, and heroin. Antibodies recognize their target molecules through molecular shapes, functional groups, and electronic properties. Since opioid drug metabolites share a large portion of their structures with their parent drugs, antibodies raised against the metabolites also bind to the drugs, albeit with varying affinities. By leveraging the cross-reactivity of these antibodies, our sensor array allows for broader detection of opioid drug exposure, including both the parent drugs and their metabolites.

The sensor array also necessitates a highly efficient platform for large-scale data collection. To achieve this goal, an automated sensing platform was built incorporating a pipetting robot, a sourcemeter, and a switching matrix (Fig. 3a). The pipetting robot handles the samples as well as the washing/gating liquid and moves the gate electrode to each sensor for FET measurements (Fig. 3b). Automated liquid handling ensures precise and reproducible sample handling, minimizing human error during experiments. Furthermore, the sourcemeter and the switching matrix communicate with the pipetting robot through a computer, enabling automated data collection. This is especially important for high-throughput analysis and seamless integration with data processing algorithms.

a The automated sensing platform. b Robot setup for the sensing experiments. c Sensing results of the sensor array comprising MOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors (MOR sensors), NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors (NOR sensors), and 6-MAM-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors (6-MAM sensors). All three types of sensors showed cross-reactivity to their corresponding opioid drug, but high specificity to other types of opioid drugs and their metabolites. All relative responses were calculated by averaging multiple FET sensors tested in the experiment. The numbers of each type of sensor tested were listed in Table S1. The error bars correspond to the standard errors of the averaged relative responses.

To test the sensing performance of the sensor array, six sensor chips were prepared for each type of sensor, and each sensor chip was tested against one type of sample with varying concentrations ranging from 1 ag/mL to 1 µg/mL. Although there were sensor-to-sensor variations that came from sensor fabrication processes, the utilization of the developed automated sensing platform significantly reduced manual intervention during the experiments and aided in better standardization across experiments, therefore improved data reliability and facilitated direct comparisons between different sensors.

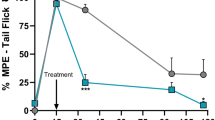

Sensing data collected using the automated sensing platform is illustrated in Fig. 3c. Due to the presence of the antibodies as the molecular recognition elements on the sensing surface, all three types of FET sensors showed the highest calibration sensitivity for their specific target. Among the non-specific molecules, all three types of sensors also demonstrated sensing capabilities toward the parent opioid drug, while no sensing behaviors of the sensors were observed for the other molecules.

As mentioned above, antibodies can have cross-reactivity with molecules that share similar epitopes, although the binding affinities may differ. Typically, the specific target of an antibody demonstrates a stronger binding affinity compared to other structurally similar compounds. This difference in binding affinity directly influences the sensing results of antibody-functionalized FET sensors. Observed across all three types of sensors, each sensor displayed a higher sensitivity toward its target molecule and a comparatively lower sensitivity toward the parent drug (Fig. S10).

Interestingly, even though MOR and 6-MAM also share similar structural features, both MOR sensors and 6-MAM sensors did not display similar levels of cross-reactivities for codeine and heroin, respectively. For MOR sensors, the addition of 6-MAM and heroin induced certain levels of sensor responses, which might come from the occurrence of binding, but no sensing capability toward these two species was observed. On the other hand, 6-MAM sensors showed only minimal responses for morphine and codeine. These results might indicate that the functional group at the C-6 position in the morphinan skeleton of the drug molecule (hydroxyl group for morphine and acetyl group for 6-MAM) plays a role in the ligand-antibody binding process. However, it is also worth noting that the degree of cross-reactivity of an antibody depends on factors such as antibody specificity, design of the binding site, and assay conditions (pH, temperature, etc.)47, hence further studies are needed to optimize the sensor array for improved sensing performance, enabling more accurate assessment of a person’s opioid exposure history.

While automating the sensing process has enabled large-scale testing and improved the robustness of results, the portability of the sensing system is another crucial factor in drug testing. A portable drug detection device would enable rapid on-site analysis, allowing for immediate decision-making in various scenarios, such as emergency medical response, workplace drug testing, and law enforcement. On-site detection is particularly crucial for identifying potent synthetic opioids, like fentanyl and its analogs, which are frequently mixed with other substances and can cause fatal overdoses. Enhancing portability would significantly expand the practical applications of the sensing system, improving both accessibility and responsiveness in critical situations.

Portable sensor setup

To adapt our SWCNT-based FET sensor technology into a portable setup, we started by using a light weight and portable potentiostat where a dual-channel potentiostat module (18 × 30 × 2.6 mm) (https://www.palmsens.com/product/oem-emstat-pico-module/) was integrated into a 90 × 65 mm (https://www.palmsens.com/product/oem-emstat-pico-development-kit/) circuit board (Fig. 4a). For the FET sensor, although the size of our developed sensor chip is small, one limitation in terms of incorporating the sensor chip into a portability system is the requirement of a separate gate electrode. We therefore utilized an interdigitated gold (G-IDE) electrode with an auxiliary electrode and a reference electrode, all patterned on a glass substrate. Shown in Fig. 4b, by patterning the IDEs, auxiliary electrode, and reference electrode on the same plane, the sensor configuration eliminated the need for a separate gate electrode.

a A portable potentiostat for FET measurement. b Sensor configuration. SEM images show NOR-ab immobilized on the Au gate electrode (left) and SWCNTs deposited between the interdigitated electrodes (right). c FET characteristic curve of norfentanyl sensing using the portable setup. d Calibration plot for norfentanyl using the portable setup. The concentration of norfentanyl indicated on x-axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Sc-SWCNTs were deposited onto the electrode to form the semiconducting channels of the FET sensor via DEP. The SEM image of the sc-SWCNTs deposited between the interdigitated electrodes revealed a morphology similar to that observed in our developed sensor chip (Fig. 4b).

Due to the small size of the G-IDE electrode, it was challenging to deposit AuNPs on the sc-SWCNTs using the previous setup. A different approach was adopted to immobilize the antibody on the SWCNT FET sensor. In this case, we took advantage of the gold gate for the immobilization of norfentanyl antibodies for norfentanyl sensing. Under SEM imaging, both sc-SWCNTs and small aggregates of antibodies can be observed on the gold surface (Fig. 4b). Transfer characteristics of the FET exhibited a decreased Id after antibody immobilization (Fig. S12). Repeated Id–Vg scans of the electrode in blank samples showed a ~15% change in Id, suggesting relatively stable antibody binding on the Au gate (Fig. S13). When binding of the analyte and the antibody occurs at the gate, rather than directly altering the conductance of the semiconducting channels, Id of the FET sensor changes because the capacitance at the gate/electrolyte interface alters48,49. As illustrated in Fig. 4c, the binding of norfentanyl shifted the threshold voltage of the FET transfer characteristics toward more positive gate voltages, resulting in an increase in Id with higher norfentanyl concentrations. The calibration curve confirms the sensing capability of the NOR sensor fabricated using G-IDE electrodes (Fig. 4d), demonstrating the successful integration of our sensing technology into a portable setup.

Discussion

The norfentanyl antibody-functionalized SWCNT-based FET sensors exhibited high sensitivity for the detection of norfentanyl in 1× sweat with a limit of detection of 34 pg/mL (146 pM), displaying its great potential as a non-invasive drug testing tool for fentanyl exposure. Two major factors contributed to the high sensitivity of the antibody-functionalized SWCNT FET sensors. The first one is the use of sc-SWCNTs as the sensing material. The high-purity semiconducting content of sc-SWCNTs offers high on/off ratio for FET, thus significantly enhancing the sensitivity of the sensors. The other factor is the strong binding between the drug molecule and its antibody near the sensing surface. For example, the dissociation constant (KD) of norfentanyl binding, which can be extracted from the calibration plot, was 17.1 pg/mL (73.4 pM). The high affinity between norfentanyl and norfentanyl antibody enables the sensors to probe norfentanyl molecules at very low concentrations.

Detection of a broader spectrum of opioid drugs and their metabolites has become more and more critical as the opioid epidemic continues to evolve. In the effort to expand the sensing capability of our sensing technology, a sensor array was developed based on our studies on the sensing performance of norfentanyl antibody-functionalized FET sensors. The sensor array contains MOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors, NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors, and 6-MAM-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors. Due to cross-reactivities of the antibodies, the sensor array not only demonstrated sensing capabilities for their specific opioid metabolites, i.e., morphine, norfentanyl, and 6-MAM, but also enabled detection of their parent drugs, namely codeine, fentanyl, and heroin. Furthermore, the use of an automated sensing platform standardized experimental procedures across different sensors and minimized human error and variability in measurements, greatly enhanced the reliability of the sensing data. This is especially important for high-throughput screening of opioid drugs and metabolites in human sweat, which requires large-scale testing of sensors.

Despite its promising sensing performance in artificial sweat, our current sensor platform is not yet optimized for direct application to real human samples. Two primary challenges must be addressed: sensor‑to‑sensor variability and non‑specific adsorption of complex biomolecules. Currently, the sensor fabrication process requires manual preparation of individual sensor chips, including SWCNT deposition, metal nanoparticle decoration, and antibody functionalization. Although criteria are in place to exclude unsuitable FET devices, variances in sensor characteristics—such as the conductance of the SWCNT network, the size of metal nanoparticles, and the number of antibodies—can still hinder accurate comparisons between sensors. Addressing this variability is crucial for enhancing both the sensing performance and the overall reliability of the platform. To achieve this, we plan to develop an automated sensor fabrication protocol, leveraging techniques such as printing50,51 or dip coating52,53 to enable mass production of SWCNT-based FET sensors with improved uniformity. In addition, the biochemical complexity of real human sweat samples poses another challenge of non‑specific interactions that can mask specific analyte signals. To address this, it is important to evaluate the cross-reactivity of opioid antibodies with non-opioid small molecules commonly found in human sweat (e.g., creatinine, histidine) to ensure these components do not interfere with specific target–antibody binding. Furthermore, to mitigate non-specific adsorption on the sensor surface, the development of a blocking layer on the sensor surface is required to prevent unwanted binding of non-specific species, such as salts, proteins, and other metabolites. Yet, blocking tests using a polymer-based blocking buffer (0.2% Tween 20 and 4% polyethylene glycol) did not yield a significant reduction in non-specific adsorption of artificial sweat (Fig. S11). Consequently, further exploration of alternative blocking chemistries is necessary to optimize the sensing surface and maximize signal-to-noise ratio.

Going forward, we anticipate further expanding of the sensor array to incorporate both specific and non-specific SWCNT-based FET sensors with the support of the automated sensing system. Specific FET sensors utilize recognition elements on the sensing surface to selectively detect target opioids, while non-specific FET sensors, such as those decorated with metal nanoparticles, capture broader chemical interactions. Moreover, machine learning algorithms can then analyze complex sensor response patterns, improving the differentiation and classification of various opioid compounds26. By integrating the automated sensor array approach and machine learning-assisted data analysis, our opioid sensing technology has the potential to enable high-throughput, non-invasive opioid screening, providing rapid and accurate assessments of patients’ opioid exposure history.

In summary, we investigated the use of norfentanyl antibody-functionalized Au-SWCNT FET sensors for detecting norfentanyl in sweat samples. By incorporating a washing step to reduce interference from sweat components, the NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors demonstrated high sensitivity toward norfentanyl, achieving a limit of detection of 34 pg/mL (146 pM). To further enhance the sensing capabilities, a sensor array was developed and integrated into an automated sensing platform. The sensor array contains FET sensors functionalized with antibodies specific to morphine, norfentanyl, and 6-MAM. Notably, cross-reactivity among structurally similar compounds further extended the detection range of the sensor array, enabling the detection of both the opioid metabolites and their parent drugs. The developed opioid screening platform offers a powerful tool for obtaining comprehensive insights about a patient’s opioid exposure history. Moreover, our sensor technology was successfully adapted into a portable sensing setup, bringing it one step closer to real-world applications that require rapid and reliable opioid screening.

Methods

Device fabrication

The sensor chips were fabricated on a Si/SiO2 wafer, each has a size of 2.6 × 2.6 mm. Source and drain electrodes were patterned on the substrate, and the channel length is 6 µm. Semiconductor-enriched single-walled carbon nanotubes (IsoSol-S100, Raymor Industries Inc.) were dispersed in toluene at a concentration of 0.02 mg/mL. Sc-SWCNTs were deposited between the source and the drain electrodes via dielectrophoresis (DEP). The applied bias voltage was 10 V, the ac frequency was 100 kHz, and the deposition time was 120 s. Excess carbon nanotubes were removed after DEP, and the sensor chip was annealed at 200 °C for 1 h before use.

AuNP decoration on the sc-SWCNTs was achieved via bulk electrolysis of 1 mM HAuCl4 (in 0.1 M HCl) solution employing a three-electrode configuration; the interdigitated electrodes on the FET sensor were treated as the working electrode, a Pt electrode was used as the counter electrode, and a 1 M Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference electrode. During bulk electrolysis, the voltage was set at –0.2 V, and the deposition time was 30 s.

To immobilize norfentanyl antibody on the FET sensors, norfentanyl antibody solution was prepared at 100 µg/mL in 1× PBS and was added to the surface of sensor chip to allow adsorption of norfentanyl antibody on AuNPs. The sensor was then placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C for at least 12 h.

For 6-MAM-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors and MOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET sensors, both antibody solutions were also prepared at 100 µg/mL in 1× PBS. The same functionalization protocol used for norfentanyl antibodies was employed to integrate both 6-MAM-ab and MOR-ab onto the FET sensors.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy was performed on a Si/SiO2 chip using a ZEISS Sigma 500 VP instrument.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

AFM data were collected using Bruker multimode 8 AFM system with a Veeco Nanoscope IIIa controller in tapping mode. AFM images and height information were obtained in Gwyddion software.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman characterization of the devices was performed using an XplorA Raman-AFM/TERS system. The Raman spectra were recorded using a 638 nm (24 mW) excitation laser operating at 10% power.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy data were generated on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 Xi XPS instrument using monochromatic Al Kα X-rays as the source. A 650 μm spot size was used, and the samples were charge compensated by using an electron flood gun.

FET measurements

Opioid drug solutions—including fentanyl, norfentanyl, codeine, morphine, heroin, and 6-MAM—were all prepared in 1× artificial sweat. The artificial sweat was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Cat. No. 01-335-996). The sensing experiment began with a blank measurement using blank artificial sweat as the sample, followed by testing the opioid solutions from the lowest to the highest concentration. For each sensor, 10 µL sample was applied and allowed to incubate for 10 min. After incubation, unbound analytes were rinsed off with a 1000-fold diluted PBS (0.001× PBS), and the FET characteristics were subsequently recorded in the same gating medium.

FET transfer characteristics were recorded using a Keithley 2602B sourcemeter. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode was used as the gate electrode, and the bottom of the gate electrode was immersed in the gating medium before starting a FET measurement. During the test, a fixed source-drain voltage was applied at 50 mV, and the gate voltage was swept from +0.6 V to −0.6 V relative to a 1 M Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The gating medium employed was 0.001× PBS to ensure consistent ionic strength during the measurements.

Statistical analysis

A sensing device was classified as functional only if it satisfied both of the following criteria: ION > 10 µA and ION/IOFF > 10. Only devices meeting these requirements were included in the statistical analysis of sensor performance.

Sensor responses were quantified using the equation R = ΔI/I₀ at Vg = −0.3 V, where I₀ is the source-drain current measured in the blank sample (1× sweat) when Vg = −0.3 V, and ΔI represents the difference between the current in the sample and that in the blank. The calibration plots were generated by plotting the average relative responses of all working devices against the logarithm of the analyte concentration. The error bars shown on the calibration curve correspond to the standard error of the relative responses obtained from all the FET devices tested. The number of NOR-ab@Au-SWCNT FET devices tested to calculate the absolute relative response in Fig. 2b was six. For all calibration curves shown in Fig. 3c, the number of devices tested for each type of sensor was listed in Table S1.

To determine the calibration sensitivity, the calibration curve was fitted using a 4-parameter logistic model, and the calibration sensitivity was defined as the largest slope of the near-linear segment of the fitted curve. Next, to determine the linear working range of the sensor, the second derivative of the fitted curve was computed. The x-axis values correspond to the two extrema in the second-derivative curve were then identified as the two bounds of the linear working range of the sensor54,55.

The limit of detection was calculated following the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry definition56. Firstly, we calculated the smallest sensor response that could be reliably distinguished, denoted as \({x}_{L}\), using the equation \({x}_{L}={\bar{x}}_{B}+k{s}_{B}\). In this equation, \({\bar{x}}_{B}\) represents the mean of the blank measures, \({s}_{B}\) is the standard deviation of the blank measures, and k is set to 3 to achieve a confidence level of 99.6%. From the calibration curve shown in Fig. 2b, we found \({\bar{x}}_{B}=\,0.16408\), \({s}_{B}=0.060489\), and \({x}_{L}=0.345547\). The corresponding concentration of norfentanyl at this sensor response (i.e., the LOD) was then determined by interpolating this value from the fitted calibration curve.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, Z. & Wang, P. Point-of-care drug of abuse testing in the opioid epidemic. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 144, 1325–1334 (2020).

Tokranova, N., Cady, N., Lampher, A. & Levitsky, I. A. Highly sensitive fentanyl detection based on nanoporous electrochemical immunosensors. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 20165–20170 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Fentanyl assay derived from intermolecular interaction-enabled small molecule recognition (IMSR) with differential impedance analysis for point-of-care testing. Anal. Chem. 94, 9242–9251 (2022).

Muthusamy, A. K. et al. Three mutations convert the selectivity of a protein sensor from nicotinic agonists to s-methadone for use in cells, organelles, and biofluids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 8480–8486 (2022).

Schramm, W., Smith, R. H., Craig, P. A. & Kidwell, D. A. Drugs of abuse in saliva: a review. J. Anal. Toxicol. 16, 1–9 (1992).

Kwong, T. C., Magnani, B. & Moore, C. Urine and oral fluid drug testing in support of pain management. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 54, 433–445 (2017).

Salomone, A. et al. Detection of fentanyl analogs and synthetic opioids in real hair samples. J. Anal. Toxicol. 43, 259–265 (2019).

Salomone, A. et al. Targeted and untargeted detection of fentanyl analogues and their metabolites in hair by means of UHPLC-QTOF-HRMS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413, 225–233 (2020).

Carelli, C. et al. Old and new synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids analysis in hair: a review. Talanta Open 5, 100108 (2022).

Bazargan, M., Mirzaei, M., Amiri, A. & Mague, J. T. Opioid drug detection in hair samples using polyoxometalate-based frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 62, 56–65 (2023).

Huestis, M. A., Cone, E. J., Wong, C. J., Umbricht, A. & Preston, K. L. Monitoring opiate use in substance abuse treatment patients with sweat and urine drug testing. J. Anal. Toxicol. 24, 509–521 (2000).

Milone, M. C. Laboratory testing for prescription opioids. J. Med. Toxicol. 8, 408–416 (2012).

Hudson, M. Drug screening using the sweat of a fingerprint: lateral flow detection of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cocaine, opiates and amphetamine. J. Anal. Toxicol. 43, 88–95 (2019).

Bordin, D. M. et al. Analysis of stimulants in sweat and urine using disposable pipette extraction and gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry in the context of doping control. J. Anal. Toxicol. 46, 991–998 (2022).

Plouffe, B. D. & Murthy, S. K. Fluorescence-based lateral flow assays for rapid oral fluid roadside detection of cannabis use. Electrophoresis 38, 501–506 (2017).

Brunelle, E., Thibodeau, B., Shoemaker, A. & Halamek, J. Step toward roadside sensing: noninvasive detection of a thc metabolite from the sweat content of fingerprints. ACS Sens. 4, 3318–3324 (2019).

Xue, W. et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of drugs of abuse in sweat by multiplexed capillary based immuno-biosensors. Analyst 145, 1346–1354 (2020).

Fakayode, S. O. et al. Electrochemical sensors, biosensors, and optical sensors for the detection of opioids and their analogs: pharmaceutical, clinical, and forensic applications. Chemosensors 12, 58 (2024).

Yence, M., Cetinkaya, A., Kaya, S. I. & Ozkan, S. A. Recent developments in the sensitive electrochemical assay of common opioid drugs. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 54, 882–895 (2024).

Marenco, A. J., Pillai, R. G., Harris, K. D., Chan, N. W. C. & Jemere, A. B. Electrochemical determination of fentanyl using carbon nanofiber-modified electrodes. ACS Omega 9, 17592–17601 (2024).

Li, M. et al. High-performance fentanyl molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensing platform designed through molecular simulations. Anal. Chim. Acta 1312, 342686 (2024).

Ghalkhani, M., Sohouli, E. & Dehkordi, Z. S. Electrochemical sensor based on mesoporous g-C3N4/N-CNO/gold nanoparticles for measuring oxycodone. Sci. Rep. 14, 17221 (2024).

Habibi, M. M. et al. Machine learning-enhanced drug testing for simultaneous morphine and methadone detection in urinary biofluids. Sci. Rep. 14, 8099 (2024).

Conrado, T. T. et al. Sensitive, integrated, mass-produced, portable and low-cost electrochemical 3d-printed sensing set (SIMPLE-3D-SenS): a promising analytical tool for forensic applications. Sens. Actuators B. Chem. 427, 137215 (2025).

Shao, W., Zeng, Z. & Star, A. An ultrasensitive norfentanyl sensor based on a carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistor for the detection of fentanyl exposure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 37784–37793 (2023).

Shao, W., Sorescu, D. C., Liu, Z. & Star, A. Machine learning discrimination and ultrasensitive detection of fentanyl using gold nanoparticle-decorated carbon nanotube-based field-effect transistor sensors. Small 20, e2311835 (2024).

Sheng, H. et al. Autonomous closed-loop mechanistic investigation of molecular electrochemistry via automation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2781 (2024).

Gerroll, B. H. R., Kulesa, K. M., Ault, C. A. & Baker, L. A. Legion: an instrument for high-throughput electrochemistry. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 3, 371–379 (2023).

Alden, S. E. et al. High-throughput single-entity electrochemistry with microelectrode arrays. Anal. Chem. 96, 9177–9184 (2024).

Pence, M. A., Rodríguez, O., Lukhanin, N. G., Schroeder, C. M. & Rodríguez-López, J. Automated measurement of electrogenerated redox species degradation using multiplexed interdigitated electrode arrays. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 3, 62–72 (2023).

Pence, M. A., Hazen, G. & Rodríguez-López, J. An automated electrochemistry platform for studying pH-dependent molecular electrocatalysis. Digit. Discov. 3, 1812–1821 (2024).

Liu, Z., Bian, L., Shao, W., Hwang, S. I. & Star, A. An automated electrolyte-gate field-effect transistor test system for rapid screening of multiple sensors. Digit. Discov. 4, 752–761 (2025).

Fan, Y., Goldsmith, B. R. & Collins, P. G. Identifying and counting point defects in carbon nanotubes. Nat. Mater. 4, 906–911 (2005).

Michael, Z. P. et al. Probing biomolecular interactions with gold nanoparticle-decorated single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 20813–20820 (2017).

Mikhlin, Y. et al. XAS and XPS examination of the Au-S nanostructures produced via the reduction of aqueous gold(III) by sulfide ions. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 177, 24–29 (2010).

Vitale, F. et al. Mono- and bi-functional arenethiols as surfactants for gold nanoparticles synthesis and characterization. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 103 (2011).

Tan, Y. H. et al. A nanoengineering approach for investigation and regulation of protein immobilization. ACS Nano 2, 2374–2384 (2008).

Yang, D., Kroe-Barrett, R., Singh, S. & Laue, T. IgG charge: practical and biological implications. Antibodies 8, 24 (2019).

Harvey, C. J., LeBouf, R. F. & Stefaniak, A. B. Formulation and stability of a novel artificial human sweat under conditions of storage and use. Toxicol. Vitr. 24, 1790–1796 (2010).

Das, P. & Zhou, R. Urea-induced drying of carbon nanotubes suggests existence of a dry globule-like transient state during chemical denaturation of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 114, 5427–5430 (2010).

Najafi Chermahini, A., Teimouri, A. & Farrokhpour, H. A DFT-D study on the interaction between lactic acid and single-wall carbon nanotubes. RSC Adv. 5, 97724–97733 (2015).

Rodarte, J. V. et al. Structures of drug-specific monoclonal antibodies bound to opioids and nicotine reveal a common mode of binding. Structure 31, 20–32 (2023).

Ban, B. et al. Novel chimeric monoclonal antibodies that block fentanyl effects and alter fentanyl biodistribution in mice. MAbs 13, 1991552 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sensing the charge state of single gold nanoparticles via work function measurements. Nano Lett. 15, 51–55 (2015).

Kim, S. N., Rusling, J. F. & Papadimitrakopoulos, F. Carbon nanotubes for electronic and electrochemical detection of biomolecules. Adv. Mater. 19, 3214–3228 (2007).

Heller, I. et al. Identifying the mechanism of biosensing with carbon nanotube transistors. Nano Lett. 8, 591–595 (2008).

Dias, C. et al. Electrochemical immunosensor for point-of-care detection of soybean Gly m TI allergen in foods. Talanta 268, 125284 (2024).

Mulla, M. Y. et al. Capacitance-modulated transistor detects odorant binding protein chiral interactions. Nat. Commun. 6, 6010 (2015).

Nguyen, T. T. K. et al. Triggering the electrolyte-gated organic field-effect transistor output characteristics through gate functionalization using diazonium chemistry: application to biodetection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 113, 32–38 (2018).

Homenick, C. M. et al. Fully printed and encapsulated SWCNT-based thin film transistors via a combination of R2R gravure and inkjet printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 27900–27910 (2016).

Sun, J. et al. Fully R2R-printed carbon-nanotube-based limitless length of flexible active-matrix for electrophoretic display application. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 1901431 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Aligned, high-density semiconducting carbon nanotube arrays for high-performance electronics. Science 368, 850–856 (2020).

Liu, H. Y. et al. Mass production of carbon nanotube transistor biosensors for point-of-care tests. Nano Lett. 24, 10510–10518 (2024).

Sebaugh, J. L. & McCray, P. D. Defining the linear portion of a sigmoid-shaped curve: bend points. Pharm. Stat. 2, 167–174 (2003).

Kaps, M., Moura, A. S. A. M. T., Safranski, T. J. & Lamberson, W. R. Components of growth in mice hemizygous for a MT/bGH transgene. J. Anim. Sci. 77, 1148–1154 (1999).

IUPAC. ‘Limit of Detection’ in IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The work at the University of Pittsburgh was supported by the Chem-Bio Diagnostics program grant HDTRA1-21-1-0009 from the Department of Defense Chemical and Biological Defense program through the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA). Raman characterization performed in the University of Pittsburgh Dietrich School Materials Characterization Laboratory (RRID: SCR_025127) and services and instruments used in this project were graciously supported, in part, by the University of Pittsburgh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. conceived the research project. W.S. performed device fabrication, device characterizations, FET measurements, and data analysis. Z.Z. performed sensor fabrication and SEM characteristics.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, W., Zeng, Z. & Star, A. Detection of opioids and their metabolites in sweat by carbon nanotube FET sensor array. npj Biosensing 2, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00051-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00051-0

This article is cited by

-

Innovations in Non-Invasive Biomarker Discovery: Unraveling the Molecular Landscapes of Human Skin

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)