Abstract

An increasing number of patients with oesophageal or gastric cancer are being diagnosed with colorectal lesions. This single-centre, retrospective study assessed the risk of colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer. 170 patients were enrolled in the early oesophagogastric cancer group, of whom 113 (66.47%) had colorectal lesions. 238 individuals were included in the control group, among whom 38 (15.97%) were diagnosed with colorectal lesions. The incidence of colorectal lesions between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05), and patients with early oesophagogastric cancer had a risk of colorectal lesions (odds ratio = 10.434, 95% confidence interval = 6.516–16.708). Multivariate analysis identified three independent risk factors: faecal occult blood test positivity, oesophagogastric lesion diameter >2 cm, and the presence of multiple oesophagogastric lesions. These findings suggest that the early oesophagogastric cancer increased the risk of colorectal lesions, particularly among individuals with the identified risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Socioeconomic development and associated shifts toward Westernised diets and sedentary lifestyles have contributed to a rising global burden of colorectal lesions, positioning these conditions as a critical public health priority. Colorectal cancer (CRC) currently ranks as the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths and the third most common malignancy worldwide, with an increasing incidence among young adults in both developed and developing countries1,2,3. Approximately 70%–90% of CRC cases arise from colorectal adenomas through sequential genetic mutations and chromosomal instability4. CRC, along with oesophageal cancer (EC) and gastric cancer (GC), is now among the top ten newly diagnosed cancers in China5. In Jiangsu Province, for instance, the 2020 incidence rates reached 36.00 per 100,000 for CRC, 41.06 per 100,000 for GC, and 31.62 per 100,000 for EC. The corresponding mortality rates were 16.61 per 100,000 for CRC, 31.39 per 100,000 for GC, and 26.88 per 100,000 for EC, underscoring the urgency of addressing oesophagogastric cancer and colorectal malignancies6.

Established risk factors for colorectal adenomas and CRC include smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, gender, and family history. Notably, smoking and alcohol consumption are also well-documented risk factors for upper gastrointestinal cancers, particularly EC and GC7,8,9. In addition to these shared risk factors, oesophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancers can undergo similar precancerous changes driven by APC gene mutations10,11. Furthermore, the pathogenesis of EC, GC, and CRC has been linked to alterations in gut microbiota. For example, Fusobacterium nucleatum has been implicated in both EC and CRC progression through immunosuppressive mechanisms and activation of oncogenic signalling pathways12. Helicobacter pylori infection, a major risk factor for GC, may also promote CRC by downregulating intestinal immunity and inducing mucus-degrading microbial profiles13. These findings suggest potential interconnections between oesophagogastric cancers and colorectal lesions. Of particular clinical significance is the observation that oesophagogastric cancer patients frequently develop colorectal lesions: 7%–16% of EC patients develop secondary CRC, while CRC is the most common second primary malignancy among GC patients14,15,16,17. This cross-compartmental tumour association highlights the critical need for a systematic understanding of the relationship between oesophagogastric cancers and colorectal lesions.

Although colorectal adenomas have been extensively studied as primary precancerous lesions, early warning signs for colorectal lesions in patients with oesophagogastric cancer remain inadequate. Current evidence predominantly focuses on advanced-stage oesophagogastric cancer, with limited attention given to early-stage cases. This knowledge gap leaves two key questions unresolved: Does early oesophagogastric cancer increase the risk of colorectal lesions? What risk factors predispose patients with oesophagogastric cancer to developing colorectal lesions?

Therefore, this study systematically investigates the risk of colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer and further analyses associated risk factors based on the findings. The results are reported as follows.

Results

Indications for colonoscopy and demographic characteristics

The primary indications for colonoscopy among all individuals were recorded, with no significant differences observed between groups (Table 1). The demographic characteristics of 170 patients with early oesophagogastric cancer and 238 controls were compared (Table 2). No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of gender distribution, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, alcohol history, family history, or comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (all P > 0.05).

Risk of intestinal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer

The early oesophagogastric cancer group demonstrated a higher prevalence of colorectal lesions compared to the control group (66.47% [113/170] vs. 15.97% [38/238], P < 0.05), along with significantly greater histopathological diversity (Table 3). In the control group, all detected lesions were conventional adenomas (38/238, 15.97%), comprising only tubular (34 cases, 14.29%) and tubulovillous subtypes (4 cases, 1.68%). The early oesophagogastric cancer group exhibited a broader neoplastic spectrum, including tubular adenomas (92 cases, 54.12%), tubulovillous adenomas (8 cases, 4.71%), serrated adenomas (4 cases, 2.35%), adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (7 cases, 4.12%), and invasive adenocarcinoma (2 cases, 1.18%). Furthermore, univariate analysis showed that patients with early oesophagogastric cancer had a 10.43-fold increased risk of developing colorectal lesions compared to controls (odds ratio [OR] = 10.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 6.52–16.71, P < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis of colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer

Among patients with early oesophagogastric cancer, no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed across the subgroups of early GC (60.6%), early EC (34.1%), and synchronous oesophageal–gastric cancer (5.3%) (P > 0.05; Table 4). Although patients with synchronous early oesophageal and gastric cancer exhibited the highest incidence of colorectal lesions (88.89% vs. 66.99% in the GC subgroup and 62.07% in the EC subgroup), these differences did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.322).

Analysis of risk factors for colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer

Comparison of baseline data between patients with and without colorectal lesions in the early oesophagogastric cancer group revealed no significant differences (P > 0.1) across multiple parameters, including age, BMI, haemoglobin level, albumin, D-dimer, gender distribution, smoking history, alcohol consumption, DM, hypertension, nutritional risk, tumour markers (alpha-fetoprotein [AFP], carbohydrate antigens [CA125, CA199, CA724, CA242], and carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA]), maximum lesion diameter, mid-oesophageal involvement, and gastric antrum involvement (Tables 5 and 6). However, three variables showed statistically significant differences: positive faecal occult blood test, multiple early oesophagogastric cancer lesions, and lesion diameter greater than 2 cm (P < 0.05). Family history demonstrated borderline statistical significance (P < 0.1).

In multivariate analysis, a positive faecal occult blood test (OR = 4.509), lesion diameter greater than 2 cm (OR = 2.095), and multiple early oesophagogastric cancer lesions (OR = 2.932) were identified as independent risk factors for colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer (Table 7).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study demonstrates a significant association between early oesophagogastric cancer and colorectal lesions. Compared with the control group, early oesophagogastric cancer increased the risk of colorectal lesions, and three independent risk factors were identified: positive faecal occult blood test (FOBT), lesion diameter greater than 2 cm, and the presence of multiple early oesophagogastric cancers. These findings support the implementation of intensified colorectal surveillance for patients with early oesophagogastric cancer, particularly when these risk factors are present.

In this study, patients with early oesophagogastric cancer exhibited both a higher incidence and an elevated risk of colorectal lesions compared with the control group. This result is consistent with previous studies that have reported increased colorectal risk in oesophagogastric cancer populations, where similar lesion rates have been documented18. Specifically, Yoshida et al. and Kim et al. identified colorectal lesions in 65.4% of oesophageal cancer patients and 50.5% of patients with gastric tumours, respectively19,20. Notably, limited evidence is available regarding early-stage oesophagogastric cancers and their association with colorectal lesions. Baeg et al. reported a 63.3% incidence of colorectal lesions in patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), with ESCC doubling the risk of colorectal lesions (OR = 2.157) and early-stage ESCC showing an even higher risk (OR = 3.347)21. A recent prospective study further demonstrated that patients with early gastric tumours had substantially higher colorectal adenoma rates than controls (55.5% vs. 27%, OR = 4.99), although no colorectal cancer cases were identified22.

Regarding the study findings, the control group demonstrated a higher proportion of colorectal adenomas (61.18%) but a lower incidence of colorectal carcinomas (4.12%). This discrepancy may be attributed to the study’s focus on patients diagnosed with early oesophagogastric cancer and the relatively short interval between diagnosis and colonoscopy (6 months), which may have limited cancer progression. Nevertheless, these observations also underscore the critical importance of early screening. Furthermore, while previous studies have reported colorectal lesion rates of 27%–42.8% in control groups, our control cohort exhibited a lower prevalence of intestinal lesions (15.97%). This discrepancy may be due to differences in cohort selection, bowel preparation quality, and limited sample size. Specifically, our controls were asymptomatic individuals drawn from health-conscious populations who likely maintained healthier lifestyles, potentially resulting in a lower baseline risk of colorectal neoplasia compared with the general population. Additionally, suboptimal bowel preparation significantly affects adenoma detection rates. In this study, bowel preparation for the control group was conducted outside the hospital setting, with limited pre-procedural education and guidance, which may partially explain the lower detection rate of colorectal lesions in the control group.

Having established an association between early oesophagogastric cancer and colorectal lesions, we further analysed the risk factors for colorectal lesions in these patients. Prior studies on colorectal lesions in oesophageal or gastric cancer populations have primarily focused on baseline characteristics, identifying age, metabolic syndrome, body weight, smoking history, and alcohol consumption as established risk factors19,23,24. Our analysis did not replicate these associations. However, we identified three risk factors: a positive faecal occult blood test, lesion diameter greater than 2 cm, and the presence of multiple early oesophagogastric cancers. FOBT is widely recognised as a non-invasive screening tool for colorectal cancer25. While prior research has linked tumour length and multifocality in oesophagogastric cancer with survival outcomes and lymph node metastasis26,27,28,29,30, our findings establish their novel association with colorectal lesion risk. This suggests that morphological characteristics of primary tumours may contribute synergistically to multisite gastrointestinal carcinogenesis.

This single-centre retrospective study has inherent limitations. The relatively small sample size, particularly in the subgroup analyses of early cancer cohorts, may compromise the precision of the findings. Furthermore, the early cancer group consisted exclusively of patients who met endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) criteria, thereby excluding individuals with smaller lesions managed by alternative endoscopic approaches. Despite these limitations, the study possesses notable strengths. First, we specifically focused on early-stage cancers and proposed a relationship between early oesophagogastric cancer and colorectal lesions. Second, the data were derived from a consecutive cohort of ESD-eligible patients over the past two years, ensuring contemporary clinical relevance. Building on this foundation, we further analysed the risk factors for colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophageal or gastric cancer, aiming to improve the accuracy of colorectal screening in this patient population.

In summary, this study demonstrates that patients with early oesophagogastric cancer exhibit an elevated risk of colorectal lesions. A positive faecal occult blood test, lesion diameter greater than 2 cm, and the presence of multiple early oesophagogastric lesions were identified as significant risk factors for colorectal lesions in this population.

Methods

Study design

In 2018, the American Cancer Society lowered the recommended age to initiate colorectal cancer screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. However, in 2023, the Society reported a continued increase in colorectal cancer incidence among adults aged 40–54 years, a trend that has persisted since the mid-1990s31. In parallel, age-specific incidence and mortality rates for oesophageal cancer in China show a marked increase beginning at age 4032. These epidemiological patterns suggest that age 40 may serve as a clinically meaningful threshold for implementing endoscopic screening protocols aimed at early cancer detection. Based on this rationale, we retrospectively evaluated the medical records of patients aged 40–80 years who attended Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. Early oesophageal cancer and early gastric cancer were defined as malignancies of the oesophagus or stomach that were pathologically confirmed through endoscopic biopsy and represented the initial detectable phase of the disease. According to the latest guidelines from the Japan Oesophageal Society and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, early oesophageal cancer is defined as T1a stage in the TNM classification system, while early gastric cancer includes both T1a and T1b stages. Based on the site of involvement, early oesophagogastric cancers were further categorised as early EC, early GC, or synchronous oesophageal–gastric cancer. Colorectal lesions were pathologically confirmed and included adenomas, adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and adenocarcinomas. We compared the risk of colorectal lesions between patients with early oesophagogastric cancer and healthy control subjects, and we identified risk factors for colorectal lesions in the cancer group. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (approval number: 2021-477-02). All participants provided written informed consent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

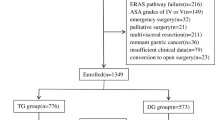

Patients who underwent ESD for early oesophagogastric cancer at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital between January 2022 and December 2023 and completed their first colonoscopy within six months after diagnosis were included in this study. These patients were recommended for colonoscopy based on their eligibility under age-appropriate colorectal cancer screening guidelines, the presence of established risk factors for colorectal neoplasia, and the absence of any prior colonoscopy history. As these patients underwent endoscopic procedures during hospitalisation, only a subset proceeded with colonoscopy screening within the short follow-up window. All included cases were managed by endoscopic resection only (without surgical resection) and were pathologically confirmed as early oesophagogastric cancer through endoscopic biopsy. A total of 170 eligible patients with early oesophagogastric cancer were enroled in the study group (Fig. 1). The control group comprised 238 asymptomatic individuals who underwent combined outpatient gastroscopy and colonoscopy screening during the same period. These participants exhibited no neoplastic lesions on gastroscopy and had no endoscopic history within the preceding five years. Patients were excluded if they had a history of malignancy, prior gastric or colorectal surgery, familial adenomatous polyposis, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal polyps, or missing data.

From 232 patients undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early esophagogastric cancers with timely colonoscopy screening, we excluded 31 non-early cancers, 28 with comorbidities/prior surgeries, and 3 with missing data. The final cohort (n=170) comprised 58 esophageal cancers, 103 gastric cancers, and 9 combined esophagogastric cancers.

Data collection

All data were obtained from hospital medical records and structured telephone interviews. The indications for colonoscopy in all individuals were recorded. Demographic data included gender, age, BMI, smoking history, alcohol history, family medical history, DM, hypertension, and other relevant medical history. The pathological classifications and morphological features of colorectal lesions were systematically documented. The control group comprised asymptomatic individuals undergoing routine health check-ups. Most voluntarily opted for colonoscopy based on established risk factors for colorectal neoplasia, including smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and/or a family history of colorectal cancer, as well as the absence of colorectal screening in recent years. Some individuals also met the age criteria defined by colorectal cancer screening guidelines. Notably, because the control group was not recruited from a dedicated health screening centre, colonoscopy was rarely conducted as part of a formal screening programme. Consequently, FOBT and routine blood tests were not consistently performed during outpatient visits, resulting in the absence of these laboratory results for most control participants. Laboratory parameters—including haemoglobin, albumin, D-dimer, AFP, CA125, CA199, CA724, CA242, CEA, and nutritional risk assessments—were collected exclusively from the study group due to the lack of institutional laboratory data for the control group. Additional clinicopathological characteristics specific to early oesophagogastric cancer were recorded in the study cohort, including maximum lesion diameter, number of lesions, anatomical location, and histopathological classification.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test, the Mann–Whitney U-test, or analysis of variance, as appropriate based on data distribution. Categorical variables were analysed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for colorectal lesions in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer. A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ORs and 95% CIs were calculated to quantify associations. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27.0).

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study contain sensitive patient information and are not publicly available. De-identified data are available from the corresponding authors (dxtzt@126.com or chenggong_yu@nju.edu.cn) upon reasonable request, subject to institutional review and data sharing agreement.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Hossain, M. S. et al. Colorectal cancer: a review of carcinogenesis, global epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and treatment strategies. Cancers 14, 1732 (2022).

Vuik, F. E. et al. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults in Europe over the last 25 years. Gut 68, 1820–1826 (2019).

Dekker, E., Tanis, P. J., Vleugels, J. L. A., Kasi, P. M. & Wallace, M. B. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 394, 1467–1480 (2019).

Han, B. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 4, 47–53 (2024).

Renqiang, H. Incidence and mortality analysis of cancers in Jiangsu Province in 2020. Jiangsu J. Prev. Med. 35, 568–574 (2024).

Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 627–647 (2022).

Colussi, D. et al. Lifestyle factors and risk for colorectal polyps and cancer at index colonoscopy in a FIT-positive screening population. U. Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 6, 935–942 (2018).

Xie, Y., Shi, L., He, X. & Luo, Y. Gastrointestinal cancers in China, the USA, and Europe. Gastroenterol. Rep.9, 91–104 (2021).

Fang, D. C. et al. Mutation analysis of APC gene in gastric cancer with microsatellite instability. World J. Gastroenterol. 8, 787–791 (2002).

Wang, B. et al. Early diagnostic potential of APC hypermethylation in esophageal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 10, 181–198 (2018).

Ajayi, T. A., Cantrell, S., Spann, A. & Garman, K. S. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer: links to microbes and the microbiome. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1007384 (2018).

Ralser, A. et al. Helicobacter pylori promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by deregulating intestinal immunity and inducing a mucus-degrading microbiota signature. Gut 72, 1258 (2023).

Eom, B. W. et al. Synchronous and metachronous cancers in patients with gastric cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 98, 106–110 (2008).

Buyukasik, O., Hasdemir, A. O., Gulnerman, Y., Col, C. & Ikiz, O. Second primary cancers in patients with gastric cancer. Radio. Oncol. 44, 239–243 (2010).

Poon, R. T., Law, S. Y., Chu, K. M., Branicki, F. J. & Wong, J. Multiple primary cancers in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: incidence and implications. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 65, 1529–1534 (1998).

Natsugoe, S. et al. Multiple primary carcinomas with esophageal squamous cell cancer: clinicopathologic outcome. World J. Surg. 29, 46–49 (2005).

Bollschweiler, E. et al. High prevalence of colonic polyps in white males with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dis. Colon Rectum 52, 299–394 (2009).

Yoshida, N. et al. Incidence and risk factors of synchronous colorectal cancer in patients with esophageal cancer: an analysis of 480 consecutive colonoscopies before surgery. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 1079–1084 (2016).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Is colonoscopic screening necessary for patients with gastric adenoma or cancer?. Dig. Dis. Sci. 58, 3263–3269 (2013).

Baeg, M. K. et al. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients have an increased risk of coexisting colorectal neoplasms. Gut Liver 10, 76–82 (2016).

Kim, S. J., Lee, J., Baek, D. Y., Lee, J. H. & Hong, R. Early gastric neoplasms are significant risk factor for colorectal adenoma: a prospective case-control study. Medicine 101, e29956 (2022).

Park, W. et al. Metabolic syndrome is an independent risk factor for synchronous colorectal neoplasm in patients with gastric neoplasm. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 27, 1490–1497 (2012).

Miyazaki, T. et al. Clinical significance of total colonoscopy for screening of colon lesions in patients with esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 33, 5113–5117 (2013).

Meklin, J., SyrjÄnen, K. & Eskelinen, M. Fecal occult blood tests in colorectal cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis of traditional and new-generation fecal immunochemical tests. Anticancer Res. 40, 3591–3604 (2020).

Cui, J. et al. Relationship of tumor length and invasion and lymph node metastasis and relevant risk factors on survival of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. Prev. Treat. 41, 214–220 (2014).

Xu, W., Liu, X. B., Li, S. B., Yang, Z. H. & Tong, Q. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Esophagus 33, doaa032 (2020).

Alshehri, A., Alanezi, H. & Kim, B. S. Prognosis factors of advanced gastric cancer according to sex and age. World J. Clin. Cases 8, 1608–1619 (2020).

Wang, W., Liu, X., Dang, J. & Li, G. Survival and prognostic factors in patients with synchronous multiple primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma receiving definitive radiotherapy: A propensity score-matched analysis. Front Oncol. 13, 1132423 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Clinicopathological features and risk factors analysis of lymph node metastasis and long-term prognosis in patients with synchronous multiple gastric cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 19, 20 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Wagle, N. S., Cercek, A., Smith, R. A. & Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin.73, 233–254 (2023).

Chen, R. et al. Patterns and trends in esophageal cancer incidence and mortality in China: an analysis based on cancer registry data. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 3, 21–27 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.L. and X.D. drafted the paper and analysed the data of patients. X.D. and C.Y. revised the paper critically for important intellectual content. N.L. and S.X. collected and summarised relevant information. X.D. and L.W. contributed to the conception and design of the work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, N., Dou, X., Xu, S. et al. A retrospective study on colorectal lesion risk assessment in patients with early oesophagogastric cancer. npj Gut Liver 2, 14 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00026-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00026-y