Abstract

Pancreatic adenocarcinomas display foci of duct-like structures that are positive for markers of pancreatic ductal cells. The development of these tumors is promoted by conditions leading to acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, a process by which acinar cells are replaced by ductal cells. Acinar-to-ductal metaplasia has recently been shown to proceed through intermediary cells expressing Nestin. To create an in vitro system to study pancreatic adenocarcinomas, we had used an hTERT cDNA to immortalize primary cells of the human pancreas. In this report, we show that the immortalized cells, termed hTERT-HPNE cells, have the ability to differentiate to pancreatic ductal cells. Exposing hTERT-HPNE cells to sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine lead to the formation of pancreatic ductal cells marked by the expression of MDR-1, carbonic anhydrase II, and the cytokeratins 7, 8, and 19. hTERT-HPNE cells were found to have properties of the intermediary cells formed during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, which included their undifferentiated phenotype, expression of Nestin, evidence of active Notch signaling, and ability to differentiate to pancreatic ductal cells. These results provide further evidence for the presence in the adult pancreas of a precursor of ductal cells. hTERT-HPNE cells should provide a useful model to study acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and the role played by this process in pancreatic cancer development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fourth most common cause of cancer fatalities in the Western World.1 Despite increased research, pancreatic adenocarcinomas have an extremely poor prognosis and still lack early diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. At the time of diagnosis, 80% of these tumors have already spread beyond the gland to regional lymph nodes, the liver, and other sites. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas display duct-like structures and are positive for markers of pancreatic ductal cells, such as carbonic anhydrase II and cytokeratin 19 (CK19).2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Recent studies have identified pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) as a premalignant lesion.7 PanIN lesions form flat or papillary structures displaying various degree of dysplasia, with the most dysplastic lesions resembling carcinomas in situ. Importantly, these lesions carry some, but not all, of the genetic alterations found in pancreatic adenocarcinomas.7 PanIN-1 lesions display mutations in K-Ras; PanIN-2 lesions carry additional lesions affecting the INK4a locus; while the PanIN-3 lesions also show a loss of p53 and/or Smad4.8, 9, 10, 11

As shown in recent studies, conditions leading to acinar-to-ductal metaplasia can promote the formation of PanIN-like lesions in the pancreas.12, 13 In transgenic mice engineered to overexpress transforming growth factor alpha (TGFα) under the control of the acinar-specific elastase-1 promoter, acinar cells are replaced by a metaplastic ductal epithelium from which PanIN-like lesions and pancreatic adenocarcinoma develop. Crossbreeding these animals with p53 knockout increases the incidence of cancer, giving rise to tumors that display hallmarks of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, including the expression of CK19, frequent deletions of the INK4a locus, and loss of heterozygosity involving Smad4.13 Histologically, direct transitions between metaplastic and neoplastic epithelia were demonstrated, with gradual progression observed along contiguous areas.12, 13 A similar metaplasia/neoplasia sequence has also been observed in human pancreatic cancer.14 Acinar-to-ductal metaplasia can be reconstituted in vitro starting with tissue explants or primary cultures of acinar cells.15, 16, 17 Within a week of exposure to TGFα, acinar-specific markers are replaced by markers of pancreatic ductal cells. In a recent study, this process required Notch signaling and proceeded through intermediary cells expressing Nestin, a marker of the developmental precursors of the exocrine pancreas.15, 18, 19 While Notch pathway components are normally limited to rare cells of the ductal epithelia, pancreatic carcinogenesis give rise to neoplastic cells that are marked by the overexpression of these components.15 This upregulation of Notch pathway components in pancreatic cancer is consistent with the involvement of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia in disease development.

A major obstacle to rapid progress in the field of pancreatic cancer research has been the lack of a human-based cell culture system to study and recapitulate the various steps of the disease. Immortal lines of normal human cells derived from the exocrine pancreas would provide such systems. We and others have shown that the catalytic subunit of human telomerase (hTERT) can immortalize primary human cells without changing their phenotypic properties or causing cancer-associated changes.20, 21, 22, 23 In a previous report, we used an hTERT cDNA to immortalize primary human cells isolated from the exocrine pancreas, and showed that the immortalized cells were diploid and expressed wild-type K-Ras, p53 and p16INK4a.24 In this report, we show that these hTERT-immortalized cells, designated as hTERT-HPNE (human pancreatic Nestin-expressing) cells, have properties similar to that of the intermediary cells produced during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. The properties that the hTERT-HPNE cells shared with these intermediary cells included their undifferentiated phenotype, expression of Nestin, evidence of active Notch signaling, and ability to differentiate to pancreatic ductal cells. These findings confirm the presence in the adult pancreas of a precursor of ductal cells. They additionally validate the hTERT-HPNE cells as model system to study acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and the role played by this process in pancreatic cancer development.

Materials and methods

Materials

Total RNA from the human pancreas and the fetal human brain were respectively purchased from BD Biosciences Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, USA) and Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and cosmic calf serum were from HyClone (Logan, UT, USA). RPMI, DMEM, DMEM:F12 (1:1), human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF), streptomycin, penicillin G, nystatin and gentamycin were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Puromycin, propidium iodide, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and sodium butyrate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Tissue Culture Conditions

The establishment of hTERT-HPNE cells was previously described.24 Briefly, an islet-depleted Ficoll fraction derived from the pancreas of a 52-year-old organ donor was handpicked under the microscope to enrich for ductal fragments. The ensuing mixture of ducts and acini was seeded in plastic dishes to yield a primary culture, which was then treated with an antifibroblast antibody and a rabbit complement to eradicate fibroblastic contamination. The surviving cells were subsequently immortalized with the catalytic subunit of human telomerase (hTERT) to yield the hTERT-HPNE cells.

hTERT-HPNE cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Medium D was used to grow and expand hTERT-HPNE cells. Medium D contains one volume of medium M3, three volumes of glucose-free DMEM, 5% FBS, 5.5 mM glucose, 10 ng/ml EGF, and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. Medium M3 is a defined proprietary formulation optimized for the growth of neuroendocrine cells (InCell Corp., San Antonio, TX, USA). Primary fibroblasts from the human pancreas were grown in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. hTERT-IMR90, Panc1, U2OS, SW13, and SW39 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. HPAF cells were expanded in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. Treatment of hTERT-HPNE cells with sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine were performed on exponentially growing cells by the addition of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5 μM) and/or sodium butyrate (5 mM) to medium D, with the agents respectively added 3 and 2 days before harvesting the cells.

Isolation and Characterization of hTERT-HPNE Clones

To allow colony formation from individual cells, hTERT-HPNE cells were seeded at 200 cells per 150 mm dish (176.6 cm2). After 2 weeks, the 30–60 colonies that formed were trypsinized individually with the use of a cloning ring. Individual colonies were transferred onto separate wells of a 24-well plate. After serial expansion onto dishes of incrementing surface (9.6, 25, 75 and then 175 cm2), individual clones were counted and characterized for their ability to induce CK19 and for the presence of Nestin, Notch2, Jagged1, and hairy/enhancer of split 1 (HES1). Frozen stocks of each clone were made, which were kept at −135°C.

Isolation of Primary Fibroblasts from the Human Pancreas

Human pancreatic fibroblasts, which we used as negative controls, were established from a tissue sample (1 × 1 × 3 cm3 in size) dissected from the head of a human pancreas, which we obtained following the accidental death of a 15-year-old male. The sample was minced into small fragments (∼1 mm3 in volume) that were dissociated for 2 h at 37°C in DMEM/F12 (1:1) containing 2 mg/ml collagenase (EC 3.4.24.3 from Clostridium histolyticum type I; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100U/ml penicillin G, and 100U/ml nystatin. This tissue preparation was forced through the tip of a 25 ml pipette and then a 10 ml pipette (10 times each). After washing the dispersed cells with DMEM/F12 containing 5% FBS and then with serum-free DMEM/F12, cells were seeded in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 μg/ml gentamycin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100U/ml penicillin G, and 100U/ml nystatin. On the following day, the medium was exchanged for DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. Cells were expanded in this medium until first confluence, at which point population doublings were arbitrarily set to 0.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Genomic DNA contamination was eliminated using an RNase-free DNase according to the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Reverse transcriptions and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed as described previously.24 Sequences of PCR primers used and sizes of expected products are listed in Table 1. Annealing temperatures (52–60°C) were calculated using the ‘prime’ feature of the GCG package. Amplifications were for 25–35 cycles, depending on the PCR primer pair. PCR products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and revealed with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed with PBS, harvested by scraping, and lysed in a buffer containing 0.5% Igepel CA30, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 120 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 8. Western blot analyses were performed as described previously.24 Primary antibodies included mouse monoclonal antibodies against Nestin (clone 25; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), CK19 (clone A53-B/A2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Notch2 (clone C651.6DbHN; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, USA). To confirm equal loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with a goat polyclonal antibody against cytoplasmic actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Cells seeded on glass coverslips were washed in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and fixed at room temperature for 30 min in HistoChoice (AMRESCO Inc., Solon, OH, USA). Cells were washed with PBS, exposed to −20°C methanol for 2 min, and then washed with PBS. After blocking the samples for 30 min in PBS containing 10% goat serum, primary antibodies against CK19 and/or Nestin were added to a final dilution of 1:100. As primary antibodies, we used a mouse monoclonal antibody against CK19 (clone A53-B/A2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against Nestin (CHEMICON International, Temecula, CA, USA). After 1 h, samples were washed with PBS containing 10% goat serum, and signals were revealed by the addition of fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Secondary antibodies used were a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC) anti-mouse immunoglobulin (IgG) antibody and/or a Texas red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 10% goat serum; Jackson Immunoresearch Lab., West Grove, PA, USA). After 1 h, samples were washed with PBS containing 10% goat serum and then with PBS. Samples were mounted in 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-containing Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) or else were stained with propidium iodide (1 μg/ml), washed with distilled water, and subsequently mounted in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, AL, USA). Images were viewed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped with an ORCA-ER digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). Images were collected and processed using the OpenLab software of Improvision Inc. (Boston, MA, USA).

Results

hTERT-HPNE Cells Display Evidence of Active Notch Signaling

Acinar-to-ductal metaplasia can be recapitulated in vitro starting with primary cultures of pancreatic acinar cells.25 In vitro, this conversion proceeds through the formation of short-lived intermediates marked by the expression of Nestin.15 In a previous report, we had used an hTERT cDNA to immortalize primary human cells of the adult pancreas, and found that the hTERT-immortalized cells expressed Nestin (Figure 1a–c).24 In this report, we asked whether these cells, designated as the hTERT-HPNE cells, might represent an immortalized population of intermediary cells, such as those generated during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. In the adult pancreas, Nestin is also expressed in endothelial and stellate cells.15, 26, 27 To distinguish between these possibilities, hTERT-HPNE cells were examined for the presence of other markers of endothelial cells (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), thrombomodulin, and VE-cadherin), stellate cells (desmin, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)), and acinar-to-ductal intermediates (Notch pathway components).15, 26, 28, 29 Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis showed that the hTERT-HPNE cells lacked the expression of markers of endothelial and stellate cells (Figure 1a). While absent from the hTERT-immortalized cells, all of these markers could readily be detected in the human pancreas with the exception of GFAP (Figure 1a). GFAP was absent from the human pancreas, but was detected in the human fetal brain (data not shown). These results indicated that the hTERT-HPNE cells were devoid of stellate and endothelial cells.

hTERT-HPNE cells coexpress Nestin with components of the Notch pathway. (a) RT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of Nestin, Notch2, and markers of endothelial cells and stellate cells. RNA isolated from hTERT-HPNE cells and the adult human pancreas were reverse transcribed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase. Resulting cDNA were subsequently amplified with PCR primers against the indicated mRNA. β-actin was used as an internal standard against sample-to-sample variation. (b) Detection of the Nestin and Notch2 proteins in hTERT-HPNE cells. Western blot analyses were performed with antibodies against Nestin and Notch2. Human pancreatic fibroblasts were used as negative controls for the expression of Nestin and Notch2. β-actin was used as a loading control. (c) Components of the Notch-signaling pathway are expressed in hTERT-HPNE cells. Using primers against the indicated mRNA, RT-PCR were performed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase. Clones M3 to M21 were established after seeding the hTERT-HPNE cells at clonal density and isolating the resulting colonies with the use of cloning rings. glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as an internal standard against sample-to-sample variation.

As documented by Western blot and RT-PCR, numerous components of the Notch-signaling cascade were expressed in hTERT-HPNE cells (Figure 1a–c). These components included a Notch receptor (Notch2), a Notch ligand (Jagged1), and a downstream target of this pathway (the HES1 gene). Neither Nestin nor Notch2 were detected in a primary culture of human pancreatic fibroblasts, thereby excluding fibroblasts as a possible source of hTERT-HPNE cells (Figure 1b). To further characterize the hTERT-immortalized population, hTERT-HPNE cells were seeded at clonal density to allow the formation of colonies from individual cells. Separate clones were subsequently examined for the presence of Nestin and Notch pathway components. Of 14 clones analyzed, all contained the Nestin mRNA (Figure 1c; data not shown). As shown in Figure 1c, similar results were observed for Notch pathway components, including the Notch2 (5/5 colonies), Jagged1 (5/5 colonies) and HES1 (5/5 colonies) mRNAs. These findings indicated that the hTERT-HPNE population was homogenous for the presence of cells that coexpressed Nestin with components of the Notch pathway. Coexpression of these markers had previously been observed in the intermediary cells formed during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia,15 thereby suggesting that hTERT-HPNE cells might be related to these intermediates.

hTERT-HPNE Cells have the Intrinsic Ability to Differentiate to Pancreatic Ductal Cells

During acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, intermediary cells are only transiently observed before they spontaneously convert to pancreatic ductal cells.15 Thus, the long-term cultivation of these short-lived intermediates would be predicted to require alterations inhibiting their spontaneous conversion to ductal cells. To examine whether epigenetic alterations involving changes in chromatin structure and/or promoter methylation might be blocking their differentiation, hTERT-HPNE cells were exposed to inhibitors of histone deacetylases (sodium butyrate) and DNA methyltransferases (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine), and were subsequently examined for the expression of CK19, a protein of the intermediary filaments whose expression in the pancreas is limited to the ducts.5, 6 Our analysis revealed that the exposure of these cells to both sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine results in the induction of CK19, as detected by Western blot (Figure 2a), RT-PCR (Figures 2b and 5a) and immunofluorescence (Figures 3 and 4). As shown by Western blot analysis, the CK19 protein was readily detected in cells exposed to the two drugs, but was undetectable in those treated with no drugs or with either drug alone (Figure 2a). This induction of CK19 in hTERT-HPNE cells was observed in 3 of 3 independent experiments. Importantly, exposure to sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine did not result in the induction of CK19 in other unrelated human cell lines (Figure 2a), which included U2OS ovarian cancer cells, hTERT-expressing IMR90 fibroblasts, and two lines of SV40-immortalized fibroblasts (termed SW13 and SW39). These results demonstrate that the induction of CK19 by the two drugs is strictly cell type-specific and an intrinsic property of the hTERT-HPNE cells.

Induction of CK19 in hTERT-HPNE cells by sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. (a) Detection of the CK19 protein in hTERT-HPNE cells and unrelated human cell lines. hTERT-HPNE cells and indicated cell lines were exposed to no drug, sodium butyrate, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, or to both drugs. Western blot analysis was performed with an anti-CK19 mouse monoclonal antibody, which detected bands of 40 and 37 kDa, respectively, corresponding to intact CK19 and its fragment, CYFRA21-1. Pancreatic cancer cell lines HPAF and Panc1 served as positive controls for the presence of CK19. β-actin was used as internal standard against sample-to-sample variation. (b) Induction of the CK19 mRNA in hTERT-HPNE cells. RNA from hTERT-HPNE samples identical to those described in (a) were reverse transcribed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase. Resulting cDNA were subsequently amplified using PCR primers against the indicated mRNA. Pancreatic cancer cell line HPAF served as positive control for the expression of the CK19 mRNA. β-actin was used as an internal standard against sample-to-sample variation.

Selective and coordinated induction of pancreatic ductal cell markers in hTERT-HPNE cells. Cells were exposed to no drug (−) or to both sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (+). RNA from treated cells were reverse transcribed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of reverse transcriptase. Resulting cDNA were subsequently amplified with PCR primers against the indicated mRNA. β-actin was used as an internal standard against sample-to-sample variation. (a) Markers of pancreatic ductal cells. Pancreatic cancer cell line Panc1 served as positive control. (b) Markers of the endocrine pancreas. Total human pancreatic RNA was used as positive control.

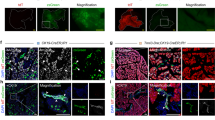

Detection of CK19 in hTERT-HPNE cells by immunofluorescence. hTERT-HPNE cells exposed to no drug (a) or to both sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (b) were stained with an anti-CK19 mouse monoclonal antibody, which was subsequently detected by the use of a secondary antibody conjugated to FITC. In cell populations treated with the two drugs, CK19-positive cells are observed that display a green fluorescent network of cytoplasmic filaments. In both cell populations, nuclei are stained red by the use of propidium iodide. Magnification equals × 100.

Dual-color immunofluorescence of hTERT-HPNE cells for detection of Nestin and CK19. hTERT-HPNE cells were exposed to sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. The Nestin (a) and CK19 (b) proteins were detected in the treated cells with secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas Red and FITC, respectively. Images of Nestin, CK19, and cell nuclei were merged in panel (c). Cell nuclei were revealed with DAPI. Although its level was consistently reduced in cells expressing CK19, Nestin was present in all cells. Magnification equals × 100.

To validate our Western blot analysis, alternate methods were used to corroborate the expression of CK19 in hTERT-HPNE cells. Likewise, RT-PCR analysis confirmed the presence of the CK19 mRNA in hTERT-HPNE cells exposed to both sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Figure 2b). While both drugs were needed to induce this message to its maximal level, the CK19 mRNA could still be detected in cells treated with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine alone. This induction of the CK19 mRNA in hTERT-HPNE cells was detected in 2 of 2 independent experiments. Immunofluorescence with an anti-CK19 antibody also confirmed the induction of the marker by the two drugs. Untreated populations of hTERT-HPNE cells lacked CK19 expression, while those treated with sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine contained abundant CK19-expressing cells (Figure 3). In cells that were positive, the antibody labeled a network of filaments localized in the cytoplasm. High levels of CK19 were detected in 11.7±1.8 percent of treated cells (n=2 independent experiments), thereby providing an explanation for the low levels of CK19 observed in the treated cells compared to pancreatic cancer cell lines HPAF and Panc1 (Figure 2a and b).

To assess whether this partial conversion to CK19 positivity might result from population heterogeneity, hTERT-HPNE cells were plated at clonal density to allow the formation of colonies from individual cells. Seven separate clones were subsequently tested for their ability to induce CK19 following sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Before drug treatment, all clones were positive for Nestin and none displayed CK19 expression (data not shown). As documented by immunofluorescence, all of the seven clones gave rise to 10–20% CK19-expressing cells following drug exposure (data not shown). Hence, this incomplete conversion of hTERT-HPNE cells could not be attributed to population heterogeneity. This analysis additionally showed that Nestin-positive clones can give rise to CK19-expressing cells, thereby implying a precursor–progeny relationship between these cell types. This possibility was directly tested in experiments of dual-color immunofluorescence performed with antibodies against CK19 and Nestin. Following exposure to the two drugs, Nestin expression decreases concomitantly with the induction of CK19 (Figure 5a; data not shown). To establish that the CK19-expressing cells were derived from precursors that contained Nestin, we used dual-color immunofluorescence to detect transitional cells coexpressing the two markers. Our data show that Nestin was still present, albeit at lower levels, in all of the CK19-positive cells detected post-treatment (Figure 4). These findings demonstrate that the CK19-expressing cells are derived from Nestin-positive precursors, and not from other minor components of the hTERT-HPNE population.

To delineate the extent of the phenotypic changes elicited by the two drugs, we extended our analysis to markers of the endocrine pancreas and other markers of pancreatic ductal cells, including carbonic anhydrase II (CAII), p-glycoprotein (multidrug resistance (MDR-1)), as well as CK7 and CK8. In the adult pancreas, these four markers are normally limited to the ducts, with the exception of the expression of CK8 in both ducts and acini.5, 30, 31 RT-PCR analysis showed that several markers of pancreatic ductal cells were concomitantly induced by the two drugs, including carbonic anhydrase II, CK7, CK8 and CK19 (Figure 5a). These markers were absent from the untreated cells but could readily be detected following drug treatment. Ductal marker MDR-1 was present both before and after drug treatment, and was modestly induced by the two drugs (Figure 5a). In contrast to markers of pancreatic ductal cells, expression of Notch2 and Nestin was respectively unchanged and decreased after treatment with two drugs (Figure 5a). hTERT-HPNE samples were also examined for the expression of markers of the endocrine pancreas, including insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin. These endocrine cell markers were absent from all of the hTERT-HPNE samples, but could readily be detected in a sample of human pancreatic RNA, which served as positive control (Figure 5b). Results from this analysis revealed that the effects of the combined drug treatment were gene specific, causing individual markers to be unaffected, induced, or else repressed by the two drugs. These coordinated changes produced a phenotype nearly identical to that of Panc1 cells, a tumorigenic derivative of pancreatic ductal cells (Figure 5a; compare lanes 1 and 5). Collectively, these results indicate that the hTERT-HPNE cells have the ability to give rise to pancreatic ductal cells.

Discussion

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fourth most common cause of cancer deaths in the Western World.1 Pancreatic adenocarcinomas have an extremely poor prognosis and lack early diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Mounting evidence now suggests that acinar-to-ductal metaplasia plays a vital role in the initiation of pancreatic cancer development.12, 13, 14, 15 In vitro, this process has been determined to proceed through intermediary cells characterized by the expression of Nestin as well as evidence of active Notch signaling.15 To study acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and its role in pancreatic cancer development, an established line of these intermediary cells would represent an invaluable tool. In a previous report, we had used an hTERT cDNA to establish the hTERT-HPNE cells, and found that the cells expressed Nestin.24 In this report, we show that the hTERT-HPNE cells have properties identical to that of the intermediary cells observed during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. Characteristics that the hTERT-HPNE cells shared with these short-lived cells included their undifferentiated phenotype, expression of Nestin, evidence of active Notch signaling, and ability to differentiate to pancreatic ductal cells. These similarities suggest that the hTERT-HPNE cells represent an immortalized population of these intermediary cells.

DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases are components of epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene transcription.32 In this report, we show that inhibitors of these enzymes synergize to convert hTERT-HPNE cells to pancreatic ductal cells. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that a differentiation program intrinsic to the hTERT-HPNE cells is engaged during this conversion. First, the two inhibitors did not cause a general derepression of gene transcription, but instead produced specific changes in gene expression. Thus, depending on the marker, expression was unchanged, induced, or else repressed by the two drugs (Figure 5a, b). Second, these coordinated changes were not random. Instead, they cooperated to give rise to a unique phenotype, which was indistinguishable from that of pancreatic ductal cells (Figure 5a). Third, this response to the two inhibitors was specific to the hTERT-HPNE cells, as these drugs failed to induce similar changes in other unrelated human cell lines (Figure 2a). These observations show that the hTERT-HPNE cells have the ability to initiate a differentiation program that converts them to pancreatic ductal cells. Our results show that sodium butyrate and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine synergize to initiate this program in 10–20% of cells. While the extent of this conversion may be partial, it should be noted that incomplete responses to the differentiation-promoting activities of these inhibitors have also been reported in other systems.33, 34 Importantly, partial conversions were similarly obtained with clones of hTERT-HPNE cells, thereby excluding population heterogeneity as an explanation for the incomplete response. Others have proposed that many cells may not be responding to demethylation agents because of their low efficiency of DNA incorporation, subsequent DNA demethylation, or toxicity.35

hTERT-HPNE cells were derived from an islet-depleted Ficoll fraction, which likely contained ducts, acini, and other contaminants. Yet, our current data show that these cells have become homogenous for the expression of Nestin and Notch pathway components, as shown by clonal analysis (Figure 1c) and immunofluorescence (Figure 4). From which components of the original Ficoll fraction did these cells come from? In the adult pancreas, Nestin is expressed by several distinct cell types, whereas Notch receptors are absent from most cells.15, 18, 26, 27 An intriguing possibility would be that the hTERT-immortalized cells were the product of acinar cell dedifferentiation. Once exposed to ex vivo culture conditions, acinar cells readily and effectively convert to pancreatic ductal cells.16, 17, 36 This conversion requires Notch signaling and has been shown to proceed through the formation of a Nestin-positive intermediate.15 Accordingly, hTERT-HPNE cells may be composed of acinar cells that have become arrested at this intermediary stage of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. This possibility is supported by our findings that the hTERT-immortalized cells are positive for Nestin expression, display evidence of Notch signaling, and can give rise to pancreatic ductal cells.

Little is known of the intermediary cells formed during acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, in particular whether they represent multipotent stem cells, lineage-restricted precursors, or intermediary states in a transdifferentiation process. While these drugs may not specifically be conducive to endocrine differentiation, the absence of islet cell markers in the drug-treated hTERT-HPNE cells suggests that these intermediary cells may be limited to the acinar–ductal axis. An intriguing possibility would be that these cells are the adult equivalent of the Nestin-positive cells that serve as developmental precursors of the exocrine pancreas during embryogenesis.18, 19 The hTERT-HPNE should represent an ideal model system to investigate the biological properties of acinar-to-ductal intermediates as well as their relationship to the developmental precursors of the pancreas. Very significantly, mounting evidence now suggests that acinar-to-ductal metaplasia plays a vital role in the initiation of pancreatic cancer development.12, 13, 14, 15 Thus, the hTERT-HPNE cells should also provide a invaluable new system with which to study acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, as well as the role played by this process in the early stages of pancreatic cancer development. Of particular interest is the observation that the pancreatic ductal cells produced by the differentiation of hTERT-HPNE cells differs from the native ductal cells in that they express Notch2 (Figure 5a), a marker of pancreatic cancer cells.15 Thus, it may be the expression of Notch pathway components in neoplastic cells identify these cells as having been produced by acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, as opposed to the proliferation of pre-existing ductal epithelial cells. Our previous observation that the hTERT-HPNE cells are diploid and exempt of cancer-associated changes should make these cells ideal as starting material for studies of in vitro carcinogenesis.24 Likewise, experiments in progress are now subjecting the hTERT-HPNE cells to oncogenic insults that mimic the initial steps of pancreatic cancer development, such as the oncogenic activation of K-Ras. Future studies should tell whether the early stages of the disease can be reconstituted by the transformation of these hTERT-immortalized cells.

References

Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:15–36.

Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ . Cancer of the pancreas (nonendocrine): a suggested morphologic classification. Semin Oncol 1979;6:285–297.

Frazier ML, Lilly BJ, Wu EF, et al. Carbonic anhydrase II gene expression in cell lines from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 1990;5:507–514.

Kim JH, Ho SB, Montgomery CK, et al. Cell lineage markers in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer 1990;66:2134–2143.

Bouwens L . Cytokeratins and cell differentiation in the pancreas. J Pathol 1998;184:234–239.

Vila MR, Balague C, Real FX . Cytokeratins and mucins as molecular markers of cell differentiation and neoplastic transformation in the exocrine pancreas. Zentralbl Pathol 1994;140:225–235.

Hruban RH, Wilentz RE, Kern SE . Genetic progression in the pancreatic ducts. Am J Pathol 2000;156:1821–1825.

Moskaluk CA, Hruban RH, Kern SE . p16 and K-ras gene mutations in the intraductal precursors of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 1997;57:2140–2143.

Wilentz RE, Geradts J, Maynard R, et al. Inactivation of the p16 (INK4A) tumor-suppressor gene in pancreatic duct lesions: loss of intranuclear expression. Cancer Res 1998;58:4740–4744.

Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res 2000;60:2002–2006.

Luttges J, Galehdari H, Brocker V, et al. Allelic loss is often the first hit in the biallelic inactivation of the p53 and DPC4 genes during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol 2001;158:1677–1683.

Greten FR, Wagner M, Weber CK, et al. TGF alpha transgenic mice. A model of pancreatic cancer development. Pancreatology 2001;1:363–368.

Wagner M, Luhrs H, Kloppel G, et al. Malignant transformation of duct-like cells originating from acini in transforming growth factor transgenic mice. Gastroenterology 1998;115:1254–1262.

Parsa I, Longnecker DS, Scarpelli DG, et al. Ductal metaplasia of human exocrine pancreas and its association with carcinoma. Cancer Res 1985;45:1285–1290.

Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, et al. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2003;3:565–576.

Hall PA, Lemoine NR . Rapid acinar to ductal transdifferentiation in cultured human exocrine pancreas. J Pathol 1992;166:97–103.

De Lisle RC, Logsdon CD . Pancreatic acinar cells in culture: expression of acinar and ductal antigens in a growth-related manner. Eur J Cell Biol 1990;51:64–75.

Delacour A, Nepote V, Trumpp A, et al. Nestin expression in pancreatic exocrine cell lineages. Mech Dev 2004;121:3–14.

Esni F, Stoffers DA, Takeuchi T, et al. Origin of exocrine pancreatic cells from nestin-positive precursors in developing mouse pancreas. Mech Dev 2004;121:15–25.

Jiang XR, Jimenez G, Chang E, et al. Telomerase expression in human somatic cells does not induce changes associated with a transformed phenotype. Nat Genet 1999;21:111–114.

Morales CP, Holt SE, Ouellette M, et al. Absence of cancer-associated changes in human fibroblasts immortalized with telomerase. Nat Genet 1999;21:115–118.

Yang J, Chang E, Cherry AM, et al. Human endothelial cell life extension by telomerase expression. J Biol Chem 1999;274:26141–26148.

Ouellette MM, McDaniel LD, Wright WE, et al. The establishment of telomerase-immortalized cell lines representing human chromosome instability syndromes. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:403–411.

Lee KM, Nguyen C, Ulrich AB, et al. Immortalization with telomerase of the Nestin-positive cells of the human pancreas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;301:1038–1044.

Meszoely IM, Means AL, Scoggins CR, et al. Developmental aspects of early pancreatic cancer. Cancer J 2001;7:242–250.

Lardon J, Rooman I, Bouwens L . Nestin expression in pancreatic stellate cells and angiogenic endothelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol 2002;117:535–540.

Klein T, Ling Z, Heimberg H, et al. Nestin is expressed in vascular endothelial cells in the adult human pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51:697–706.

Risau W, Flamme I . Vasculogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1995;11:73–91.

Blann A, Seigneur M . Soluble markers of endothelial cell function. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 1997;17:3–11.

Nishimori I, FujikawaAdachi K, Onishi S, et al. Carbonic anhydrase in human pancreas: hypotheses for the pathophysiological roles of CA isozymes. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999;880:5–16.

Thiebaut F, Tsuruo T, Hamada H, et al. Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:7735–7738.

Ng HH, Bird A . DNA methylation and chromatin modification. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1999;9:158–163.

Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, et al. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:12313–12318.

Fukuda K . Development of regenerative cardiomyocytes from mesenchymal stem cells for cardiovascular tissue engineering. Artif Organs 2001;25:187–193.

Chiurazzi P, Pomponi MG, Pietrobono R, et al. Synergistic effect of histone hyperacetylation and DNA demethylation in the reactivation of the FMR1 gene. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:2317–2323.

Rooman I, Heremans Y, Heimberg H, et al. Modulation of rat pancreatic acinoductal transdifferentiation and expression of PDX-1 in vitro. Diabetologia 2000;43:907–914.

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported by the Lustgarten Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research (LF 01-040), the SPORE program (CA72712), and a generous start-up package from the Eppley Institute for Research on Cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, K., Yasuda, H., Hollingsworth, M. et al. Notch2-positive progenitors with the intrinsic ability to give rise to pancreatic ductal cells. Lab Invest 85, 1003–1012 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700298

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700298

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Occult polyclonality of preclinical pancreatic cancer models drives in vitro evolution

Nature Communications (2022)

-

MARK2 regulates chemotherapeutic responses through class IIa HDAC-YAP axis in pancreatic cancer

Oncogene (2022)

-

The EGFR-HSF1 axis accelerates the tumorigenesis of pancreatic cancer

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2021)

-

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD regulates the growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Aberrant expression of a novel circular RNA in pancreatic cancer

Journal of Human Genetics (2021)