Abstract

Studies of murine severe combined immune-deficient (scid/scid) fetuses gestating in transgene-tagged immune competent dams have established high frequencies of transplacental trafficking of nucleated maternal cells. Maternal cells first appeared in thymus at gestation day (gd) 12.5 and were present in more than 90% of late gestation fetuses. Morphologically heterogeneous maternal cells were located predominantly in bone marrow and thymus and also occasionally in liver, spleen, and nonlymphoid organs. We have now evaluated maternal cell chimerism in offspring with normal lymphoid development. Genetically normal blastocysts from random-bred CD1 mice were transferred to C57BL/6J- lacZ transgene-tagged ROSA26 females. Serial sectioning of fetuses followed by histochemistry for lacZ-expressing cells was used to comprehensively define organs containing maternal cells. Fetuses, sectioned in their entirety, had no detectable maternal cells before gd 16.5. Morphologically homogenous, nucleated maternal cells were first present in fetal bone marrow cavities at gd 16.5 and were evident in all offspring in later gestation. Postnatally, maternal cells were also present in bone marrow cavities into adulthood, as determined by lacZ histochemistry and PCR amplification of the maternal transgene. The frequency of maternally derived cells in postnatal bone marrow was increased compared with late gestation, and occasionally, maternal cells were detected in postnatal spleen. The normalcy of maternal cell transfer to genetically immune competent progeny and their long-term engraftment is suggestive of a functional role for maternal cells in offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal cell chimerism of offspring has been extensively investigated in infants with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) syndromes, with engraftment of maternal T and B lymphocytes reported in up to 25% of patients (Pollack et al, 1982). These transplacentally acquired cells are functionally competent, as evidenced by their ability to induce graft-versus-host disease in some patients (Conley et al, 1984; Flomenberg et al, 1983; Le Deist et al, 1987; Suda et al, 1984; Vaidya et al, 1991). Maternal cell transfer to immune-deficient fetuses has also been reported in studies using xenogeneically engrafted scid/scid (SCID) mice. Offspring born to and suckled by human peripheral blood leukocyte (PBL)–engrafted SCID mothers acquired human cells (Ladel et al, 1992). Similarly, 40% of offspring of SCID dams engrafted with bovine PBL produced antigen-specific bovine Ig in response to antigenic challenge (Greenwood and Croy, 1993).

Although engraftment of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-mismatched maternal lymphocytes is tolerated in immune-deficient offspring, immune repertoire development in genetically normal progeny would be expected to present a barrier to widespread distribution and persistence of maternal cells. In normal pregnancy of species with hemochorial placentation (including mice and humans), some level of placental permeability to cell passage has been reported. However, specific cell subsets that traffic and the regulatory mechanisms governing their passage are not yet established. In early studies, in which PBL and erythrocytes from pregnant women were isotopically labeled and reinfused to monitor transfer to offspring, maternal cells were routinely detectable in umbilical cord blood (Desai and Creger, 1963; El-Alfi and Hathout, 1969; Zarou et al, 1963). More recently, molecular-based approaches for identification of maternal-specific alleles have also identified the presence of maternal cells in umbilical cord and fetal blood samples (Bauer et al, 2001; Briz et al, 1998; Hall et al, 1995; Lo et al, 1996; Petit et al, 1995, 1997; Scaradavou et al, 1996; Socie et al, 1994).

Using murine model systems, in which information concerning organs of maternal cell localization can be gathered, contradictory results have been generated. In an extensive study, Hunziker et al (1984) failed to find maternal lymphocytes in samples of liver, blood, or spleen of mid- to late-gestation fetuses. Conversely, other reports have documented the presence of maternal cells in one or more of these organs (Collins et al, 1980; Zhou et al, 2000). In studies of neonates, maternal cells have been identified in liver, spleen, thymus, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and blood (Arvola et al, 2000; Barnes and Holliday, 1970; Shimamura et al, 1994; Tuffrey et al, 1969; Zhou et al, 2000). In several cases, acquisition of maternal cells postnatally via lactation may have accounted for the reported chimerism. Overall, questions concerning the fate and destination of transplacentally trafficked maternal cells have not been resolved.

We previously described a novel approach to study maternal cell chimerism in immune-deficient, SCID fetuses that were transferred as embryos to immune-competent, transgene-marked dams (Piotrowski and Croy, 1996). Assessment of progeny for cells of maternal origin revealed widespread maternal cell chimerism beginning at gestation day (gd) 12.5 in fetal thymus. By late gestation (gd 18.5), chimerism was widespread in both lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs, with thymus being the most frequently chimeric site and liver having the highest proportions of maternal cells.

The present study has used this model system to evaluate maternal cell chimerism in genetically normal fetuses and postnatal animals. In this report, blastocysts from random-bred, nontransgenic CD1 parents were transferred into pseudopregnant, LacZ+ ROSA26 females (H2b). ROSA26 mice ubiquitously express the product of LacZ, β-galactosidase, in all nucleated cells (Friedrich and Soriano, 1999), providing a nontransferable genetic marker that was detectable both histologically and by PCR. This approach permits characterization of maternal cell chimerism with respect to its timing of initiation during pregnancy, the sites of maternal cell localization within fetuses, and the frequency of chimerism within and between litters. Persistence and distribution of maternal cells was also followed postnatally. We provide evidence for the onset of maternal cell chimerism in bone marrow during late gestation in all fetuses, with persistence of maternal cells at this site in adult progeny. This documentation that maternal cell chimerism is a regular occurrence in normal pregnancy is suggestive of a functional role for maternal cells in offspring.

Results

Maternal Cells Are Not Present in Fetal Tissues by gd 15.5

To verify that our model system allowed identification of individual β-galactosidase-positive (β-gal+) cells, ROSA26 and CD1 control animals were first assessed. As expected, serial sectioning and β-gal staining of ROSA26 fetuses from matings of ROSA26 parents [gd 8.5 (n = 2), gd 12.5 (n = 1), and gd 15.5 (n = 1)] demonstrated a ubiquitous, uniformly blue cytoplasmic stain in fetal tissues (data not shown). Negative control fetuses derived from matings of CD1 parents at gd 8.5 (n = 1), 15.5 (n = 1), 16.5 (n = 2), and 18.5 (n = 1) were examined to establish whether certain tissues might inherently express the bacterial LacZ gene (data not shown). Using our staining protocol, β-gal reactivity was found in late gestation kidney and intestine of CD1 fetuses (n = 1 at each of gd 16.5, 18.5, and 19.5) but not in any other organ. Postnatal CD1 organs were also harvested and analyzed individually. Importantly, postnatal lymphoid organs were also devoid of endogenous lacZ expression (liver, thymus, and spleen, n = 1 at each of 2 and 6 weeks of age). A serially sectioned forelimb of a 2-week-old CD1 control mouse was also negatively stained. Notably, the appearance of endogenous lacZ expression in kidney and intestine was qualitatively different from transgene-associated staining of ROSA26 cells. Endogenous lacZ expression had a diffuse staining pattern that was not always delineated by cell membranes, in contrast to the cytoplasmic, cell-associated stain of ROSA26 cells. Thus, in studies of CD1 fetuses that had gestated in ROSA26 dams, cytoplasmic lacZ expression was considered to represent the presence of maternal cells. Positive staining detected in kidney or intestine was not considered to represent maternal cell chimerism when detected, even where such staining was associated with cell cytoplasm.

To determine whether maternal cells are found in early and mid-gestation fetuses, 22 CD1 fetuses recovered from ROSA26 during this developmental period were assessed histologically for β-gal+ cells. Transplacental trafficking was not expected to commence before establishment of placental architecture. Thus, gd 8.5 was the earliest age examined, because this closely precedes development of the hemochorial placenta and its circulation at gd 9.5 to 10. As anticipated, maternal and fetal components of gd 8.5 and 10.5 placenta could be distinguished using β-gal staining. The maternal tissues, comprising the uterus and decidual portion of the placenta, were entirely β-gal+, in contrast to the apposed, β-gal− fetal trophoblasts of CD1 origin. At the interface of the maternal and fetal tissues, intermingling of cells of each origin could be distinguished and individual β-gal+ cells were discernible (Fig. 1A). At gd 8.5 and 10.5, an average of 180 and 350 histologic sections, respectively, were prepared and examined per implantation site (defined as the fetus plus intact placenta). No positively stained cells were present in organs, cavities, or circulation of the fetuses themselves (summarized in Table 1). At mid-gestation, offspring from two separate litters at each time point were selected for analysis [gd 12.5 (n = 4), gd 14.5 (n = 3), and gd 15.5 (n = 3)]. These older fetuses generated an average of 825 serial sections per specimen. Again, no β-gal staining was evident in any mid-gestation CD1 fetus that had gestated in ROSA26 (Table 1). This result differs from our previous work with genetically immune-deficient SCID fetuses, in which β-gal+ maternal cells were detected by mid-gestation (Piotrowski and Croy, 1996).

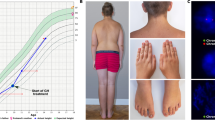

Maternal cells are localized in fetal and postnatal tissues. CD1 progeny that were transferred as embryos to transgenic, lacZ-expressing ROSA26 mothers were evaluated histochemically for the protein product of lacZ, β-galactosidase (β-gal) (blue cells) on serial cryostat sections. A, Maternal nucleated cells and maternal blood vessels are evident infiltrating the fetal placenta at gd 10.5 (× 200). B and C, Maternal cells were predominantly localized in late gestation bone marrow (gd 16.5 shown) (× 200, B; × 400, C). D, Rare liver chimerism was present in a single gd 16.5 fetus, evident as an isolated scattering of blue cells (× 200). E and F, At 2 weeks postnatally, maternal cells persisted in high numbers lining the bone marrow cavities (× 400, E; × 600, F).

Maternal Cells Are First Detected in Bone Marrow at gd 16.5

Randomly selected CD1 fetuses from three ROSA26 litters were assessed histologically for maternal cells at gd 16.5 (Table 2). At this age, an average of 996 sections were prepared and examined per fetus. Positively stained cells were found in four of six fetuses examined, situated in close association with developing bone marrow cavities, specifically, along the bony spicules that line the hematopoietic regions (Fig. 1, B and C). The hematopoietic cords themselves lacked β-gal reactivity. Morphologically, β-gal+ cells were round and lymphocyte like, having sizes between 7 and 14 μm in diameter, based upon the presence of the same cell in only one to two consecutive, 7-μm tissue sections. The frequency of detection of β-gal+ cells in bone marrow ranged from 2.2% to 29.4% of the tissue sections examined, suggesting that their numbers vary considerably at this age. Only one gd 16.5 chimera had rare β-gal+ cells in liver, morphologically similar to those in bone marrow (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that maternal cell chimerism of genetically immune-competent fetuses occurs in late gestation.

Maternal Cells Are Present in Bone Marrow of All Fetuses Before Birth

To further investigate the normalcy of late gestation chimerism, histologic analyses were extended to gd 18.5 (n = 2) and 19.5 (n = 2). All fetuses had β-gal+ cells lining the marrow cavities of most bones but not in any other tissue (Table 2). Compared with β-gal+ cells at gd 16.5, the positively stained cells at gd 18.5 to 19.5 were larger, with estimated diameters of 20 to 30 μm based on their appearance in three or four consecutive 7- to 12-μm tissue sections. The β-gal+ cells were also more numerous within any given bone marrow cavity. Overall, by gd 19.5, maternal cells were present in 75% of the 400 total tissue sections that were prepared from each specimen. Because 100% of fetuses were heavily chimeric by gd 18.5 to 19.5, maternal cell transfer to fetuses seems to be a normal event initiated at or after gd 16.5.

Postnatal Persistence of Maternal Cells in Bone Marrow of Offspring

To define the duration of maternal cell persistence in bone marrow, postnatal CD1 mice that had gestated in ROSA26 were evaluated for the presence of the maternal transgene. Because the large size of postnatal mice precluded serial cryostat sectioning of entire animals, individual organs were dissected and prepared for either histochemistry or PCR. Histochemical analysis for β-gal+ cells in bone marrow was done using serially sectioned whole forelimbs of 2-week-old CD1 littermates derived from embryo transfer (n = 2). β-gal+ cells were consistently present in bone marrow cavities (Table 3). The positively stained cells were similarly situated as in developing fetal bones, specifically, lining the intraluminal marrow spaces of the bones (Fig. 1, E and F). Compared with peripartum fetuses, β-gal+ cells were strikingly more numerous, because they were present in all tissue sections that included bone marrow and were also much larger (estimated to be at least 30 μm in diameter). In fact, because of their increased size, maternal cells seemed to have developed extensions into hematopoietic cords in some regions. The increased maternal cell numbers in postnatal bone marrow were suggestive of an expanding maternal cell population. For older offspring of ROSA26, serial cryostat sectioning of 6-week-old forelimb was attempted but was unsuccessful because of advanced ossification of the adult bone. Thus, for analysis of 6- to 12-week-old offspring, a PCR-based approach was used to detect the ROSA26 transgene in CD1 bone marrow.

The sensitivity of the PCR approach for maternal cell detection was validated using prepared mixtures of ROSA26 and CD1 cells. Lymphocytes from bone marrow plugs of ROSA26 and CD1 adults were prepared as a series of 1 in 10 dilutions of ROSA26 to CD1 cells ranging from 1:10 to 1:106 for DNA extraction and PCR amplification. ROSA26 cells were still detectable by PCR when they represented 1:105 cells (Fig. 2A) but not at 1:106 (data not shown). Thus, in the bone marrow plug of a CD1 animal born to a ROSA26 dam, from which at least 106 cells can be recovered, as few as 10 ROSA26 cells would be detectable.

PCR-based identification of maternal transgene expression in postnatal tissues. A, To establish the sensitivity of the PCR protocol for detection of ROSA26 cells in CD1 offspring, bone marrow cell suspensions were prepared from adult ROSA26 and CD1 mice and mixed as a series of 1 in 10 dilutions for DNA extraction. PCR was then performed using primers specific for the ROSA26 transgene (as per “Materials and Methods”). Lane 1, CD1 negative control; lane 2, 1:10 of ROSA26 to CD1 cells; lane 3, 1:100; lane 4, 1:1 000; lane 5, 1:10,000; lane 6, 1:100 000. Cyclophilin DNA was amplified as an internal control (top panel). B, Verification that flushing bone marrow cavities allows recovery of ROSA26 cells from chimeric CD1 mice. Femoral DNA from CD1 offspring with known chimerism (established histologically) was PCR amplified for the ROSA26 transgene. Lane 1, ROSA26-positive control bone marrow; lanes 2 to 3, bone marrow from two CD1 offspring of ROSA26 (2 weeks old); lane 4, CD1-negative control bone marrow. Control = cyclophilin. C, The maternal transgene was identified in spleen and bone marrow of a proportion of postnatal CD1 mice that had been transferred as embryos to ROSA26. Representative PCR positive samples are depicted (refer to Table 3 for summary of all tissues analyzed by PCR). Lane 1, ROSA26-positive control bone marrow; lane 2, 2-week spleen; lane 3, 2-week spleen; lane 4, 6-week spleen; lanes 5 to 7, 12-week spleen; lane 8, 6-week bone marrow; lane 9, 12-week bone marrow. Control = β actin. No amplification product was observed from CD1-negative control DNA (represented in B, lane 4, which was PCR amplified in the same reaction run).

Because the maternal cells could have been physically anchored within bone marrow cavities, it was also necessary to confirm that these cells were recoverable by flushing out bone marrow plugs. To establish that ROSA26 cells could be harvested from CD1 bone marrow plugs, PCR analysis was applied to the 2-week-old animals in which chimerism had been established histologically in forelimbs (n = 2; Fig. 2B). PCR amplification of femoral DNA confirmed the presence of the ROSA26 transgene in both CD1 mice, indicating that maternal cells in bone marrow were accessible for PCR analysis.

To determine the normalcy of postnatal bone marrow chimerism, DNA was PCR amplified from a randomly selected tibia or femur of embryo transfer-derived adults (Table 3, representative samples shown in Fig. 2C). At 6 weeks of age, the ROSA26 transgene was detected in bone marrow plugs of six of six littermates. Similarly, littermates at 10 to 12 weeks old all tested positive for ROSA26 cells. These data suggest that maternal cells were stably engrafted in adult bone marrow.

Maternal Cells Are Found Postnatally in Spleen

Although our studies demonstrated an almost exclusive localization of maternal cells in bone marrow during fetal life, this finding did not preclude more widespread dissemination postnatally. Possible seeding of peripheral organs by maternal cells was examined in postnatal CD1 offspring derived from ROSA26 mothers, as summarized in Table 3. Histochemistry and/or PCR to detect β-gal+ cells in thymus and liver of 2- to 6-week-old offspring demonstrated no maternal cell chimerism. Splenic chimerism of CD1 progeny was also investigated, because spleen was consistently chimeric in SCID offspring (Piotrowski and Croy, 1996) and because this organ might harbor a blood-borne population. Using both methods for ROSA26 cell detection, 8 of 17 offspring had splenic chimerism at 2 to 12 weeks of age (representative PCR samples shown in Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the chimeric mice varied in age from neonates to adults, suggestive of the capacity for long-term engraftment in some individuals. One putative explanation for the apparent nonchimeric state of some spleens is that the level of chimerism was too low to detect (<1 in 105 maternal cells for PCR). However, chimerism was also absent in two animals assessed by histochemistry, a method that allows visualization of single cells. The sensitivity of this technique was exemplified by the successful detection of extremely rare liver chimerism at gd 16.5 (Fig. 1D and Table 2). In summary, based on the use of both methods of maternal cell identification, bone marrow chimerism is typical postnatally, whereas the occurrence of maternal cells in spleen is variable. Overall, the finding that maternal cells are not restricted to bone marrow indicates that they likely circulate postnatally and may stably engraft at additional sites.

Discussion

In this report we provide evidence for maternal cell chimerism in bone marrow of genetically normal, late gestation fetuses and postnatal mice. Because our approach evaluated all fetal tissues, contradictory findings of past reports could be resolved. Hunziker et al (1984), who did not find maternal cell chimerism in an extensive study of 172 mice at gd 15 to 19 and at 24 hours postnatally, did not examine bone marrow. Hunziker et al (1984) found maternal cells in livers of only two progeny and postulated that such rare chimerism may be responsible for runting, which is observed in only a small proportion of offspring. Our experiments, showing maternal cells in one of ten prenatal livers, confirm Hunziker's finding of rare chimerism in liver but do not support the notion that chimerism has pathologic consequences. Both the present study and that of Hunziker et al (1984) seem to contradict Collins et al (1980) who reported a maternal H-2 antigen in livers of up to 92% of gd 17 to 18 blastocyst transfer–derived allogeneic fetuses. These findings were confounded by the fact that 8% of the fetuses did not react with antisera to their own MHC but were reported as having maternal MHC.

The present report describes splenic maternal cell chimerism only at postnatal stages, whereas bone marrow is chimeric earlier, suggestive of lactational transfer of cells to spleen and/or seeding of cells from chimeric bone marrow after birth. Indeed, lactational transfer of maternal cells to both bone marrow and spleen has been documented (Arvola et al, 2000; Shimamura et al, 1994; Zhou et al, 2000). In previous studies, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cells have been tracked in offspring born to and/or suckled by GFP-expressing dams (Arvola et al, 2000; Zhou et al, 2000). Importantly, when GFP-expressing dams were used for foster nursing only (and not as embryo transfer recipients), lactationally transferred maternal cells in liver were present only transiently and spleen was infrequently chimeric, suggesting that postnatally acquired cells do not survive long-term (Zhou et al, 2000). Conversely, where progeny were both born to and suckled by GFP+ dams, thereby introducing a transplacental source of maternal cells, chimerism could still be detected at 3 and 6 months postnatally (Arvola et al, 2000). These data suggest that transplacentally trafficked populations have a capacity for long-term engraftment, whereas lactationally acquired cells provide more transient early neonatal immunity.

The results of this study suggest that the ability of maternal cells to persist in offspring is affected by the MHC relationship between the mother and her fetus. In MHC-disparate offspring, two putative factors that might contribute to elimination of transplacentally trafficked maternal cells include alloreactivity and/or competition for niches with developing endogenous lymphocytes. Conversely, in a syngeneic maternofetal relationship, only the latter issue is of relevance. In the present study, inbred ROSA26 dams have the H-2b haplotype, whereas their CD1 progeny are random bred, thereby introducing MHC disparities. Conversely, the syngeneic MHC relationship between mother and offspring in the studies by Zhou et al (2000) and Arvola et al (2000) might explain the propensity for more widespread chimerism that these groups reported in prenatal animals. Indeed, whereas Zhou et al (2000) found maternal cells in thymus, liver, and spleen of a proportion of gd 18 fetuses, localization of maternal cells was found to be highly restricted during gestation of CD1 fetuses in ROSA26. Notably, in postnatal mice, Zhou et al (2000) and Arvola et al (2000) also found chimerism of bone marrow and spleen but reported a lower overall incidence (2/5 and 3/11 chimeric mice, respectively, compared with 10/10 offspring here). Notwithstanding, if MHC compatibility is actually a permissive factor for maternal cell engraftment, it is possible that the extent of chimerism was underestimated postnatally in their studies or that the maternal cells seeded additional sites that were not examined.

The timed appearance of maternal cells along bone marrow cavities suggests that they may be appropriately positioned to promote hematopoiesis. Although only four of six gd 16.5 fetuses were chimeric, this finding might reflect minor asynchronies in either the timing of transplacental cell transfer or in fetal staging, perhaps exaggerated by manipulations during blastocyst transfers. We expect that the two nonchimeric fetuses would have had maternal cells if they had been examined at a later gestational day because bone marrow was heavily populated by maternal cells in all older offspring. Interestingly, the initial appearance of maternal cells in fetal bone marrow at gd 16.5 coincides with the time of initiation of hematopoiesis at this site. Bone marrow is first colonized by hematopoietic progenitors at gd 15.5 (Delassus and Cumano, 1996). By gd 17.5, progenitors are migrating to bone marrow, the new primary lymphopoietic site. Architecture of bone marrow cavities is also elaborated, as blood-borne osteoclast progenitors migrate to centers of bone formation and become anchored in the periosteum precisely between gd 15.5 and 17.5 (Dodds et al, 1998). In this study, maternal cells were a morphologically homogenous population lining the bone marrow cavities that progressively expanded in both cell numbers and individual cell size, suggestive of an osteoclast-like phenotype. Gd 16.5 maternal cells could not be phenotyped by histologic examination, because their rarity and small size precluded preparation of alternate serial sections with β-gal and cell surface marker–specific antibodies. For postnatal mice at 2 weeks, staining of alternate serial sections for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase to identify osteoclasts was hampered by loss of enzyme activity during storage and processing of specimens for β-gal histochemistry.

This study identifies developing fetal immune competence as a determining factor in maternal cell distribution. Normal T- and B-cell differentiation seems to exclude maternal cell chimerism in organs other than bone marrow. In SCID fetuses (Piotrowski and Croy, 1996) and RAG-2 null γcnull (deficient T, B, and natural killer cell development; our unpublished observations), ROSA26 maternal cells had widespread, multiorgan localization beginning in gd 12.5 fetal thymus. In both immune-deficient strains, maternal cells of lymphoid appearance were present, presumably including T cells, based on literature demonstrating human maternal T cells in SCID offspring (Conley et al, 1984; Flomenberg et al, 1983; Pollack et al, 1982; Suda et al, 1984; Vaidya et al, 1991). In CD1 fetuses, thymic chimerism might be impeded by immune-related mechanisms or by physical space restriction imposed by developing lymphocytes that are occupying the available niches. No structural differences are seen in the placentae of these genotypes (CD1, SCID, and RAG-2 null γcnull) (Croy and Chapeau, 1990; Greenwood et al, 2000) that could account for the more extensive and earlier chimerism in lymphocyte-deficient fetuses. However, in all strains we have studied, β-gal+ maternal cells were present in bone marrow with similar morphology and appearance. Thus, maternal cell engraftment of bone marrow is selectively promoted, independent of differential lymphoid subset expansion at this site.

Bidirectional exchange of cells transplacentally has been proposed to affect both maternal and fetal health. Elevated fetal cell traffic into mothers has been associated with preeclampsia (Holzgreve et al, 1998; Zhong et al, 2001). Persistent fetal cells in scleroderma lesions has led to the suggestion that microchimerism might play a role in the pathogenesis of scleroderma or other autoimmune diseases (Nelson et al, 1998), although a comparable frequency of chimerism has been documented in scleroderma patients and healthy control subjects (Evans et al, 1999; Maloney et al, 1999). Similarly, cell movement in the opposite direction, from mother to fetus, has been correlated with development of the autoimmune diseases scleroderma (Nelson et al, 1998) and juvenile dermatomyositis (Reed et al, 2000). Maternal cell chimerism in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-incompatible maternal-fetal relationships has also been proposed to account for the tolerance of certain individuals to noninherited maternal HLA antigens (Claas et al, 1998). Indeed, Maloney et al (1999) confirmed that HLA-disparate maternal cells are maintained in immune-competent subjects into adulthood. Based on both the present report and human data, it seems that some level of maternal cell chimerism occurs normally and that differences in the numbers or functions of engrafted cell subsets likely dictate whether the outcome is health or disease. Although it is not known how maternal cell passage and survival are regulated, our report suggests that the maternal cell population is established in bone marrow during initial induction of the hematopoietic microenvironment at this site.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Random-bred CD1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, PQ). 129/Sv-Gtrosa26 (ROSA26) mice, formerly 129/Sv-TgR(ROSA26)26Sor, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). All mice were housed and mated under conventional conditions in the animal facility at the University of Guelph (Guelph, Ontario, Canada) in accordance with approved animal utilization protocols.

Timed Pregnancies and Embryo Transfers

Timed matings were prepared for embryo transfer experiments, with the morning of copulation plug detection defined as gd 0.5. CD1 females were selected for estrus and paired with CD1 males for mating. Mated CD1 females donated blastocysts for transfer on gd 3.5. Pseudopregnant blastocyst recipients were ROSA26 females 2.5 days after mating by vasectomized CD1 males. Pregnant CD1 females were euthanized using CO2 followed by cervical dislocation, and uteri were excised for blastocyst collection. Blastocysts were transferred to uteri of anesthetized ROSA26 recipients (Avertin, 0.4 ml per mouse) using established techniques (Hogan et al, 1986). The age designations of the subsequent fetal stages were assigned using the day of embryo transfer as gd 2.5. Syngeneic natural matings of ROSA26 and CD1 mice were also conducted to provide age-matched positive and negative control progeny, respectively.

Histochemistry for Detection of LacZ-Expressing Cells

At gd 8.5 to 19.5 (just before parturition), pregnant embryo transfer recipients and control mice were euthanized using CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Uteri were dissected and transected between implantation sites. For embryo transfer-derived fetuses at gd 8.5 (n = 7) and 10.5 (n = 5), intact implantation sites, including the fetuses, placentae, and maternal uterine tissue, were processed. For the older embryo transfer fetuses (n = 20), uteri were opened along the antimesometrial side and intact fetuses were removed from the placentae and processed. Postnatal CD1 mice that had gestated in ROSA26 females were euthanized at 2 or 6 weeks of age for collection of organs [limbs for bone marrow (n = 2), thymus (n = 4), liver (n = 4), and spleen (n = 2)], because the large size of neonates precluded whole body sectioning. Control tissues were also collected from age-matched CD1 and ROSA26 mice produced by natural matings. Tissues, except those required for cell suspensions, were placed into cryovials filled with Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, Indiana), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° C. Sagittal and parasagittal serial cryostat sections of unfixed tissue were prepared and mounted onto positively charged slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher Scientific, Whitby, Ontario, Cananda). Sections were cut at 7-μm thickness for fetuses between days 8.5 and 18.5 of age. Older fetuses (gd 19.5) and postnatal tissue were sectioned at 10- to 14-μm because of their larger surface areas, increased cellularity, and the progressive ossification of bone. All fetuses from gd 8.5 to 19.5 were completely sectioned. For tissues of postnatal animals, serial sections were cut at 14 μm for limbs and 12 μm for thymus, liver, and spleen. Slides were then processed for histochemical detection of β-gal+ cells. Briefly, slides were fixed in 0.1% glutaraldehyde and subsequently stained using 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-galactopyranoside (X-gal; Boehringer-Mannheim, Montreal, PQ) in dimethyl sulfoxide (Fisher Scientific) for 10 to 12 hours at 37° C. Slides were counterstained with nuclear fast red (Fisher Scientific), dehydrated, and coverslipped. Each serial section was examined by light microscopy (× 250 magnification) for identification of β-gal+ cells. Histologic examination confirmed that all CD1 fetuses recovered from ROSA26 dams were developmentally normal, according to established criteria for staging of murine fetal development (Kaufmann, 1992). Representative positive (ROSA26) and negative (CD1) control samples were included in each staining run. ROSA26 control was histologically examined to assess the distributions of nucleated cells versus extracellular components in various lymphoid organs, because β-gal+ reactivity was expected to typify the cytoplasm of nucleated cells only. CD1 controls were examined to determine endogenous β-gal staining patterns in fetuses and postnatal organs.

Preparation of Tissue for PCR

For some postnatal animals at 2, 6, 10, and 12 weeks of age, cell suspensions of bone marrow (n = 14), spleen (n = 15), and liver (n = 3) were prepared. For bone marrow, femurs and tibiae were dissected and contents of the cavities were flushed out with PBS using 22-gauge needles. Spleens and livers were dissociated by pressing through mesh stainless steel screens followed by repeated passage into a tuberculin syringe. For all tissues, red blood cells were lysed using buffer comprised of 0.15 m ammonium chloride and 1 mm potassium bicarbonate (pH 7.2). Cells from these tissues were counted using a hemocytometer. Between 106 and 107 cells were recovered per marrow cavity. For spleens, at least 107 cells were recovered. To establish the detection limit of the PCR reaction for identification of β-gal+ ROSA26 cells among CD1 cells, bone marrow cell suspensions were also prepared from CD1 and ROSA26 control animals. A series of dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:106 of ROSA26 cells in CD1 cells was prepared, with the total cell number equaling 106 per sample. Cells were stored at −80° C in 1 ml of PBS in microcentrifuge tubes before DNA extraction.

PCR Analysis for the ROSA26 Transgene

DNA was extracted from cell suspensions of postnatal mice using a QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA samples were all diluted to a concentration of 28 μg/μl because this was the lowest obtainable concentration from a bone marrow sample. In PCR reactions, 2 μl of each sample was added to a final reaction volume of 50 μl. PCR amplification was performed using a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Connecticut) using commercially available primers for genotyping of the ROSA26 transgene (The Jackson Laboratories). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primer pairs, 5′ and 3′, are as follows: GGCTTAAAGGCTAACCTGATGTG and GCGAAGAGTTTGTCCTCAACC. PCR reaction conditions used were 94° C (3 minutes) and then 34 cycles at 94° C (1 minute), 62.2° C (2 minutes), and 72 ° C (3 minutes), followed by 72° C (1 minute) using 1.5 mm MgCl2. This reaction amplified a 1-kb product. Amplification of cyclophilin or β-actin DNA served as internal controls. Primer sequences were (5′ to 3′): GACAGCAGAAAACTTTCGTGC and TCCAGCCACTCAGTCTTGG or GTCGTACCACAGGCATTGTGATGG and GCAATGCCTGGGTACATGGTGG, respectively. Positive (ROSA26) and negative (CD1) control DNA was included in each PCR reaction. No amplification of the ROSA26 transgene was ever observed in samples of CD1-negative control DNA. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.4% agarose gels (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Missouri) and stained with ethidium bromide for UV visualization.

References

Arvola M, Gustaffon E, Svensson L, Jansson L, Holmdahl R, Heyman B, Okabe M, and Mattson R (2000). Immunoglobulin-secreting cells of maternal origin can be detected in B cell-deficient mice. Biol Reprod 63: 1817–1824.

Barnes R and Holliday J (1970). The morphological identity of maternal cells in newborn mice. Blood 36: 480–490.

Bauer M, Orescovic I, Schoell WM, Bianchi DW, and Pertl B (2001). Detection of maternal DNA in umbilical cord plasma by fluorescent PCR amplification of short tandem repeat sequences. Ann NY Acad Sci 945: 161–163.

Briz M, Regidor C, Monteagudo D, Somolinos N, Garaulet C, Fores R, Posada M, and Fernandez MN (1998). Detection of maternal DNA in umbilical cord blood by polymerase chain reaction amplification of minisatellite sequences. Bone Marrow Transplant 21: 1097–1099.

Claas FH, Gijbels Y, van der Velden-de Munck J, and van Rood JJ (1998). Induction of B cell unresponsiveness to noninherited maternal HLA antigens during fetal life. Science 241: 1815–1817.

Collins GD, Chrest FJ, and Adler WH (1980). Maternal cell traffic in allogeneic embryos. J Reprod Immunol 2: 163–172.

Conley ME, Nowell PC, Henle G, and Douglas SD (1984). XX T cells and XY B cells in two patients with severe combined immune deficiency. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 31: 87–95.

Croy BA and Chapeau C (1990). Evaluation of the pregnancy immunotrophism hypothesis by assessment of the reproductive performance of young adult mice of genotype scid/scid.bg/bg. J Reprod Fertil 88: 231–239.

Delassus S and Cumano A (1996). Circulation of hematopoietic progenitors in the mouse embryo. Immunity 4: 97–106.

Desai RG and Creger WP (1963). Maternal passage of leukocytes and platelets in man. Blood 21: 665–673.

Dodds RA, Connor JR, Drake F, Field J, and Gowen M (1998). Cathepsin K mRNA detection is restricted to osteoclasts during fetal mouse development. J Bone Miner Res 13: 673–682.

El-Alfi OS and Hathout H (1969). Maternal transfusion: Immunologic and cytogenetic evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 103: 599–600.

Evans PC, Lambert N, Maloney S, Furst DE, Moore JM, and Nelson JL (1999). Long-term fetal microchimerism in peripheral blood mononuclear cell subsets in healthy women and women with scleroderma. Blood 93: 2033–2037.

Flomenberg N, Dupont B, O'Reilly RJ, Hayward A, and Pollack MS (1983). The use of T cell culture techniques to establish the presence of an intrauterine-derived maternal T cell graft in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Transplantation 36: 733–735.

Friedrich G and Soriano P (1999). Promoter traps in embryonic stem cells: A genetic screen to identify and mutate developmental genes in mice. Genes Dev 5: 1513–1523.

Greenwood JD and Croy BA (1993). A study on the engraftment and trafficking of bovine peripheral blood leukocytes in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 38: 21–44.

Greenwood JD, Minhas K, Di Santo JP, Makita M, Kiso Y, and Croy BA (2000). Ultrastructural studies of implantation sites from mice deficient in uterine natural killer cells. Placenta 2: 693–702.

Hall JM, Lingenfelter P, Adams SL, Lasser D, Hansen JA, and Bean MA (1995). Detection of maternal cells in human umbilical cord blood using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Blood 86: 2829–2832.

Hogan B, Constantini F, and Lacy E (1986). Recovery, culture, and transfer of embryos. In: Manipulating the mouse embryo. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 89–149.

Holzgreve W, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Ganshirt D, Maymon E, and Hahn S (1998). Disturbed feto-maternal cell traffic in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 91: 669–672.

Hunziker RD, Gambel P, and Wegmann TG (1984). Placenta as a selective barrier to cellular traffic. J Immunol 133: 667–671.

Kaufmann MH (1992). Postimplantation period. In: Atlas of mouse development. New York: Academic Press, 17–337.

Ladel CH, Puschner H, Kaufmann SH, and Bamberger U (1992). Human peripheral blood leukocytes transplanted on CB17 scid-scid mice are transferred to their offspring. Eur J Immunol 22: 1735–1740.

Le Deist F, Raffoux C, Griscelli C, and Fischer A (1987). Graft vs graft reaction resulting in the elimination of maternal cells in a SCID patient with maternofetal GVHd after an HLA identical bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol 138: 423–427.

Lo YM, Lo ES, Watson N, Noakes L, Sargent IL, Thilaganathan B, and Wainscoat JS (1996). Two-way cell traffic between mother and fetus: Biologic and clinical implications. Blood 88: 4390–4395.

Maloney S, Smith A, Furst DE, Myerson D, Rupert K, Evans PC, and Nelson JL (1999). Microchimerism of maternal origin persists into adult life. J Clin Invest 104: 41–47.

Nelson JL, Furst DE, Maloney S, Gooley T, Evans PC, Smith A, Bean MA, Ober C, and Bianchi DW (1998). Microchimerism and HLA-compatible relationships of pregnancy in scleroderma. Lancet 351: 559–562.

Petit T, Dommergues M, Socie G, Dumez Y, Gluckman E, and Brison O (1997). Detection of maternal cells in human fetal blood during the third trimester of pregnancy using allele-specific PCR amplification. Br J Haematol 98: 767–771.

Petit T, Gluckman E, Carosella E, Brossard Y, Brison O, and Socie G (1995). A highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction method reveals the ubiquitous presence of maternal cells in human umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol 23: 1601–1605.

Piotrowski P and Croy BA (1996). Maternal cells are widely distributed in murine fetuses in utero. Biol Reprod 54: 1103–1110.

Pollack SM, Kirkpatrick D, Kapoor N, Dupont B, and O'Reilly RJ (1982). Identification by HLA typing of intrauterine-derived maternal T cells in four patients with severe combined immunodeficiency. N Eng J Med 307: 662–666.

Reed AM, Picornell YJ, Harwood A, and Kredich DW (2000). Chimerism in children with juvenile dermatomyositis. Lancet 356: 2156–2157.

Scaradavou A, Carrier C, Mollen N, Stevens C, and Rubinstein P (1996). Detection of maternal DNA in placental/umbilical cord blood by locus-specific amplification of the noninherited maternal HLA gene. Blood 88: 1494–1500.

Shimamura M, Ohta S, Suzuki R, and Yamazaki K (1994). Transmission of maternal blood cells to the fetus during pregnancy: Detection in mouse neonatal spleen by immunofluorescence flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. Blood 83: 926–930.

Socie G, Gluckman E, Carosella E, Brossard Y, Lafon C, and Brison O (1994). Search for maternal cells in human umbilical cord blood by polymerase chain reaction amplification of two minisatellite sequences. Blood 83: 340–344.

Suda T, Thompson LF, O'Connor RD, and Bastian JF (1984). Phenotype and function of engrafted maternal T cells in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency. J Immunol 133: 2513–2517.

Tuffrey M, Bishun NP, and Barnes RD (1969). Porosity of the mouse placenta to maternal cells. Nature 221: 1029–1030.

Vaidya S, Mamlok R, Daeschner CW 3rd, Williams J, Ruth J, and Goldblum RM (1991). Suppression of graft-versus-host reaction in severe combined immunodeficiency with maternal-fetal T cell engraftment. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 13: 172–175.

Zarou DM, Lichtman HC, and Hellman LM (1963). The transmission of chromium-51 tagged maternal erythrocytes from mother to fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 88: 565–571.

Zhong XY, Holzgreve W, and Hahn S (2001). Circulatory fetal and maternal DNA in pregnancies at risk and those affected by preeclampsia. Ann NY Acad Sci 945: 138–140.

Zhou L, Yoshimura Y, Huang Y-Y, Suzuki R, Yokoyama M, Okabe M, and Shimamura M (2000). Two independent pathways of maternal cell transmission to offspring: Through placenta during pregnancy and by breast-feeding after birth. Immunology 101: 570–581.

Acknowledgements

We thank Angela Kather and Kanwal Minhas for their assistance with the histologic studies.

Supported by the Hospital for Sick Children's Foundation Toronto, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marleau, A., Greenwood, J., Wei, Q. et al. Chimerism of Murine Fetal Bone Marrow by Maternal Cells Occurs in Late Gestation and Persists into Adulthood. Lab Invest 83, 673–681 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.LAB.0000067500.85003.32

Received:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.LAB.0000067500.85003.32

This article is cited by

-

Pregnancy-induced maternal microchimerism shapes neurodevelopment and behavior in mice

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Vertically transferred maternal immune cells promote neonatal immunity against early life infections

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Stem cells in human breast milk

Human Cell (2019)

-

Immunological implications of pregnancy-induced microchimerism

Nature Reviews Immunology (2017)

-

Impact of HIV-1 infection on the feto-maternal crosstalk and consequences for pregnancy outcome and infant health

Seminars in Immunopathology (2016)