Abstract

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is a premalignant (dysplastic) lesion that is characterized by abnormal cellular proliferation, maturation and nuclear atypia. The intraepithelial distribution, density, and nature (typical or atypical) of mitotic figures are routinely utilized diagnostic criteria to grade dysplasia and to distinguish high-grade dysplasia from potential histologic mimics such as transitional metaplasia, atrophy or immature squamous metaplasia. In this study, we evaluated the total mitotic indices of the cervical epithelia in hysterectomy specimens from patients with and without dysplastic lesions and investigated a possible relationship between mitotic index and hormonal status, using the endometrial maturation phase as a surrogate indicator of the latter. Two hundred seventy-four cervices from hysterectomy specimens (135 cases without dysplasia, 33, 35 and 71 cases with grades 1, 2 and 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, respectively) were analyzed. A cervical mitotic index (total mitotic figures/10 high-power fields in the most proliferative area) was determined for each case. The endometrium in each case was classified into atrophic, early proliferative, late proliferative and secretory. For all three dysplasia grades, cases in the proliferative endometrium group always had a higher average mitotic index than those in the secretory and atrophic endometrium groups; this observation also held true for the benign cases. Furthermore, in all three dysplasia grades, the average mitotic index was always lowest in the atrophic endometrium group. Although the mitotic index showed expected patterns of increases with increasing dysplasia grades for most of the endometrial phases, this was not a universal finding. Notably, the average mitotic index for our cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 cases with late proliferative endometrium was higher than our cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 cases with secretory and atrophic endometrium. It is concluded that hormonal status, as reflected in endometrial maturation, can significantly affect the mitotic index of dysplastic squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix. Our findings confirm that the pathologic grading of dysplasia, especially in equivocal cases such as in metaplastic squamous epithelium, should not be solely dependent on the finding mitoses in the cervical squamous epithelium. The full composite of histopathologic features should form the basis for this determination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The ectocervical epithelium, as does squamous epithelium at other anatomic locations, continuously undergoes an organized program of maturation and differentiation from the basal to the superficial layers, with morphologic correlates of a progressive decrease in nuclear size, nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and a progressive increase in nuclear chromatin density, cytoplasmic size and cytoplasmic glycogen of constituent cells.1, 2 Basal cells appear to act as stem or reserve cells, whereas parabasal cells comprise the actively replicating compartment. Therefore, proliferative activity, whether evaluated by mitotic figures or the variety of available proliferative markers, should be largely confined to the lower 15% of the normal ectocervical epithelium.1, 2 Accordingly, the intraepithelial distribution, density, nature (typical or atypical) of mitotic figures, as well as immunohistochemically defined proliferative activity, have emerged as important pathologic criteria to distinguish low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia from high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and to distinguish high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia from potential histologic mimics such as transitional metaplasia, atrophy or immature squamous metaplasia.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Compared to the endometrium and vaginal epithelium, where marked variations in the estrogen receptor (ER) content occur during the menstrual cycle, much less cyclic variation of ER expression occurs in the cervical lining.20, 21, 22 Nonetheless, it has long been recognized that cervical squamous epithelial cells contain sex-steroid receptors and hence, their proliferation and differentiation are influenced, to some extent, by the menstrual cycle and/or sex-steroid hormonal levels.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Most studies have localized ERs and progesterone receptors (PRs), at minimum, to the basal and parabasal cell layers of the normal ectocervix.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 Data on a possible correlation between the localization and the extent of ERs and the menstrual cycle phase are less homogeneous. Kanai et al23 and Ciocca et al22 both reported that the expression and localization of steroid hormone receptors did not vary significantly with the phase of the menstrual cycle. In contrast, Scharl et al21 found that the intraepithelial ER localization in the proliferative phase, in postmenopausal cervices and in early gestation, were in the basal, parabasal and intermediate cells, whereas in the secretory phase, ER staining was confined to the basal and parabasal cells. Cano et al24 reported that the cervical epithelial ER content decreases during the secretory phase, whereas Mosny et al25 reported the opposite: the latter authors found that in the secretory phase, ER-positive cells may be found up to the most superficial layers, in contrast to the proliferative phase, where they are variably localized to the basal and parabasal layers. The somewhat conflicting findings of the aforementioned studies notwithstanding, it can be stated that at minimum, the cervical epithelium appears to be under some degree of hormonal influence.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

In the present retrospective analysis, we sought to explore the potential inter-relationships of these two factors—hormonal effects on the ectocervical epithelium and intraepithelial proliferative activity. Hormonal factors that significantly affect the mitotic index of normal epithelium may also theoretically influence the mitotic index of dysplastic epithelium. However, current diagnostic criteria for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, which as previously noted are partially dependent on mitotic index, do not take into account a possible role for the phase of menstrual cycle and/or hormonal status on the mitotic activity of the cervical epithelium. Herein, we evaluate the total mitotic index of the cervical epithelium in hysterectomy specimens from patients with and without cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions and investigate a possible relationship to hormonal status, using the endometrial maturation phase as a surrogate indicator of the latter.

Materials and methods

Case Selection

All hysterectomy specimens in which a squamous dysplasia of the cervix (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) was diagnosed at Yale-New Haven Hospital (New Haven, CT, USA) and Women and Children's Hospital (Los Angeles, CA, USA) between January 1, 1996 and June 30, 2001 were retrieved and analyzed. These cases represented hysterectomies specifically performed for biopsy-proven cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and hysterectomies that were performed for corpus or ovarian indications in which a cervical dysplasia was incidentally identified. For benign cases, a category that included cases of cervical squamous metaplasia without dysplasia, consecutive hysterectomies performed for a variety of benign, non-cervical indications were utilized. Approval from the institutional review boards for both institutions was obtained. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides were reviewed to confirm the diagnoses and to evaluate numbers and intraepithelial distribution of mitotic figures. Cases with moderate to marked chronic cervicitis were excluded from the study.

Morphologic Evaluation

The diagnostic criteria used for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia were based on standard guidelines enumerated by the World Health Organization and the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists (WHO/ISGYP classification).29, 30 Mitotic figures were counted as described previously.15, 31 Briefly, in each case, the entire evaluable cervical epithelium was surveyed in a consistent manner by moving the microscopic field from the superficial to deep layers. Therefore, the total surface area of cervical epithelium evaluated was dependent on the number of sections initially obtained, which generally ranged from two sections in the benign cases and up to 12 sections in the dysplastic cases. Approximately 10–50 high-power fields were assessed under × 400 magnification for each specimen. The total mitotic index represents the total number of normal and abnormal mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields of the most mitotically active area for a given specimen. As noted previously, the endometrial maturation phase was used as a surrogate indicator of the hormonal status. At least one section of the endometrium from each case was evaluated and the cases were classified into four categories based on standard criteria:1, 32 early proliferative, late proliferative, secretory and atrophic endometrium. The specimens were evaluated independently by two pathologists (YM and WZ for cases from USC and SXL and WZ for cases from Yale). For those cases with a diagnostic disagreement between the pathologists, a joint session at a double-headed microscope was used to resolve the disagreements. The final results represented findings agreed upon by both observers.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for Ki67 and p16INK4A were performed on selected cases. Immunohistochemistry was performed primarily to serve as an external validator of the rendered diagnoses in a representative sample of all the cases examined. As such, cases were selected irrespective of their endometrial maturation phases. All immunohistochemical assays were performed on 4 mm-thick unstained tissue sections and in a DakoCytomation (Carpinteria, CA, USA) Autostainer. The proliferative indices were evaluated with a monoclonal primary mouse antibody against human Ki67 antigen (clone mib-1, isotype IgG1-κ, dilution 1:100; DakoCytomation). The percentage of cells showing unequivocal nuclear staining in 10 of the most active high-power fields was estimated and constituted the Ki67 proliferative index. For p16INK4A, a mouse monoclonal antibody against the human antigen (clone E6H4) was utilized (DakoCytomation). Cases were considered positive when there was diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in the majority of cells evaluated in the area of interest.

Statistical Analysis

Where applicable, Student's t-tests was used for statistical comparisons, with P<0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic Findings

Overall clinicopathologic findings are summarized in the Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. A total of 274 cases were evaluated, of which 139 had a squamous dysplasia of the cervix. The distribution of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades for these 139 cases was as follows: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (n=33), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 (n=35), and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (n=71). The average ages for the patients in these three groups were 39, 42 and 44 years respectively. Cervical dysplasia was absent in 135 cases (benign cases, average age of patient 44 years).

Mitotic Index in Cervical Squamous Epithelium were Correlated with Corresponding Endometrial Maturation Phases

The corresponding endometrial maturation phases for each of the aforementioned groups are outlined in Table 1. The average mitotic indices for the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 and benign cases were 1.939, 4.06, 4.91 and 0.47 mitoses per 10 high-power fields, respectively (Table 1). Table 3 shows the mitotic indices for the four groups along with the corresponding endometrial maturational phases. As expected, the average mitotic index showed progressive increases from the benign cases to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 to cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3. The average mitotic index for any subgroup of the benign cases never exceeded the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3 cases, although two subgroups of the former had average mitotic indices that exceeded those of the atrophic endometrium and secretory endometrium of the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 group (Table 2). Generally, the average mitotic indices of the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and 3 groups were higher than the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 groups for most of the endometrial maturation phases. The two major exceptions were late proliferative endometrium and early proliferative endometrium of the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 group (average mitotic index 4.33 and 3.2, respectively), which were actually higher than the mitotic indices of the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 group in the atrophic endometrium and secretory endometrium phases (1.17 and 1.91 mitoses per 10 high-power fields, respectively) (Table 2). The cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 late proliferative endometrium mitotic index (4.33 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) was also higher than the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 mitotic index for atrophic endometrium and secretory endometrium (3.31 and 3.904 mitoses per 10 high-power fields, respectively). For the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia groups, cases with atrophic endometrium always had the lowest average mitotic index. For the benign group, the average mitotic index was lowest in the cases with secretory endometrium. For each of the four groups, the average mitotic indices for cases with proliferative endometrium were always the highest (Table 2). In Table 6, the mitotic index of the various endometrial maturation subgroups are compared within each dysplasia grade. Overall, the comparisons were predominantly significant (P<0.05). In one category, atrophic endometrium vs secretory endometrium, no significant differences were noted in any dysplasia grade or in the benign group.

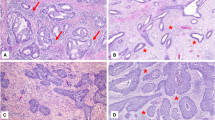

There were no abnormal mitotic figures seen in benign cervical squamous epithelium. In contrast, both abnormal and normal looking mitotic figures were seen in high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasias. The mitotic figures found in benign lesions were mainly parabasal locations, whereas locations of mitotic figures varied in the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions ranging from parabasal to topmost epithelial layers.

Immunohistochemical Findings

The staining patterns for Ki67 and p16INK4A (Tables 3 and 4) were consistent with published data.33, 34 The Ki67 PI showed a progressive increase from the benign cases (12.71) to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (25.8) to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 (37.19) to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (48.28), with the highest frequency of transmural staining in the latter. Similarly, 0, 36.36, 100 and 100% of the benign, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 cases were positive for p16INK4A, respectively. Although not all the endometrial maturation phase subgroups were represented in the cases whose proliferative indices were evaluated, the preliminary data appeared congruent with those on mitotic figures: the highest proliferative indices appeared to be in those cases with proliferative endometrium (Table 4).

Mitotic Figures in Dysplastic Epithelium

We attempted to statistically compare the mitotic indices in the various grades and to determine whether significant differences were relatable to the endometrium maturation phases. Results are summarized in Table 5 and should evaluated within the context of the limitations of small numbers in each phase. Overall, statistically significant differences in mitotic index were seen with the following comparisons: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 vs cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3 (P<0.0001), cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3 vs benign (P<0.0001) and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 vs benign (P=0.002). However, within the endometrial maturation phase subgroups, some variations were evident. As expected, the mitotic index for cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3 was significantly higher than the benign cases for all phases (P<0.0001). The average mitotic index for the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 group did not differ significantly from the ‘benign’ group for cases with atrophic, early proliferative and secretory endometrium; only in cases with late proliferative endometrium, a statistically significant difference (P=0.007) was noted between these two groups (benign vs cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1). In the distinction of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 from cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3, highly significant mitotic index differences were observed for cases in the atrophic and secretory endometrium groups (P=0.0003 and <0.0001, respectively) but not in the late proliferative endometrium and early proliferative endometrium groups (P=0.22 and 0.06, respectively).

Mitotic Figures in Metaplastic Squamous Epithelium

Of the 135 benign cases, there was notable squamous metaplasia at the transitional zone in 105 (group A) and was absent in 30 (group B). We sought to determine whether there existed any significant differences in the parameters being evaluated between these two groups. Mitotic figures found in metaplastic squamous epithelia were predominantly parabasal in location, although occasionally, rare mitoses were identified in the mid-layer of the metaplastic epithelium. Of the group A cases, mitotic indices of 0, 1, 2 and 3 were present in 67, 21, 17 and 0 cases, respectively. Parallel figures for the group B cases were 21, 4, 2 and 3 cases, respectively. p16INK4A was negative in all 135 cases. Groups 1 and 2 did not differ significantly with respect to patient's age (43 vs 46 years, P=0.28) or Ki67 proliferative index (11.2 vs 12.4, P=0.48), respectively.

Discussion

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia represents a spectrum of variably proliferative, intraepithelial squamous lesions that are considered as the precursor lesions of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix.35, 36, 37 The etiologic role played by the human papillomavirus (HPV) in the genesis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is well established.38, 39, 40 In low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HPV integration into host genome is minimal and HPV-mediated activation of host DNA synthesis occurs in non-proliferative (ie supraparabasal) cells as a manifestation of passive viral replication.40 Therefore, although proliferative activity is increased above baseline in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1, the increase is not marked. In contrast, high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasias 2 and 3 are characterized by HPV integration in host genome cells with the expression of early HPV genes in proliferation-capable cells.40, 41 The resultant clinicopathologic correlates of the latter are a basaloid proliferation with increased mitotic figures3 and significantly higher progression and persistence rates as compared to their low-grade counterparts.42 These aspects of HPV pathogenesis have formed important components of the diagnostic criteria for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and in the resolution of clinically significant differential diagnoses in this context. As previously noted, the intraepithelial distribution, density, nature (typical or atypical) of mitotic figures have emerged as important pathologic criteria for distinguishing low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia from high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and for distinguishing high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia from potential histologic mimics such as transitional metaplasia, atrophy or immature squamous metaplasia.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Mitotic figures in low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia should be confined to basal third of the epithelium and should not be numerous and should only rarely be atypical.37 High-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, in contrast, may show numerous mitoses including numerous abnormal forms throughout the epithelium.37 These criteria presume the absence of factors that may significantly affect the mitotic index of cervical epithelium outside of those intrinsic to it in benign cases or those mediated by HPV in dysplastic cases. In this study, we evaluated the inter-relationships between the mitotic index of normal and dysplastic epithelium and the endometrial maturation phase, which was used in this context as a surrogate indicator of the patients' hormonal status. Our study showed that (1) for all three cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades, cases in the proliferative endometrium group always had a higher average mitotic index than those in the secretory and atrophic endometrium groups; this also held true for the benign cases. (2) In all three cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades, the average mitotic index was always lowest in the atrophic endometrium group; in the benign group, the lowest mitotic index was in the secretory endometrium group. These findings suggest that hormonal status, at least as reflected in endometrial maturation, plays a role in the mitotic index of both normal and dysplastic epithelium. However, it is unclear if this effect is directly mediated by the sex steroid hormones or related and/or indirect factors. Direct hormonal effects should theoretically be accompanied by retention of hormonal receptors in dysplastic epithelium. However, Mosny et al25 found that the ER content of high-grade dysplastic squamous epithelium is entirely lost, whereas only faint staining is seen in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1. As outlined in Table 3, our cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 group did not show any phase-dependent variation in mitotic index that was markedly discordant with the other cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades. Kanai et al,23 in contrast, found that while ER was decreased in dysplastic epithelium, PR was increased. Thus, the precise mechanistic basis for this potential hormonal influence remains to be elucidated.

Since our dysplastic cases were so diagnosed and graded based on criteria that were comprised in part of mitotic index, the progressive increase in mitotic index from the low- to high-grade lesions was expected. However, the practical diagnostic implications of our findings are related to the potential pitfalls of relying solely on mitotic activity to distinguish high- from low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and from metaplastic squamous epithelium. It is important to note that findings of metaplastic squamous epithelium without nuclear atypia could be easily misdiagnosed as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions and result in unnecessary clinical treatment when mitoses are found in those epithelia. This determination should be a composite approach that takes into consideration cellular atypia, presence or absence of a basaloid proliferation, as well as the intraepithelial distribution, nature and density of mitotic figures.37 Notably, the average mitotic index for our cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 cases with late proliferative endometrium was higher than our cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 cases with atrophic and secretory endometrium, highlighting the potential pitfall in the sole reliance on this parameter. Practically, it is important for clinicians to provide information on menstrual status for reproductive-aged women as well as hormone replacement status for postmenopausal women and for pathologists to be aware of potential hormonal influences on the mitotic activity of cervical squamous epithelium.

One potential limitation of our study is the disproportionate representation of the studied patients in the 40–45 years age group, which raises the possibility that our findings are simply reflecting the hormonal changes in this specific age group. This disproportionate representation is likely a study population artifact that stems from the fact that hysterectomies are more likely to be performed for cervical dysplasia or benign indications such as uterine leiomyomata after reproduction is complete. In our opinion, the variety of endometrial maturation phases reflected in our data set should be sufficiently reflective of the hormonal status seen in the age groups, in which cervical dysplasia is a significant diagnostic consideration.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that hormonal status, as reflected in endometrial maturation, can significantly affect the mitotic index of dysplastic squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix. Our findings confirm that the pathologic grading of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, especially in equivocal cases, should not be solely dependent on the finding mitoses in the cervical squamous epithelium. The totality of histopathologic features should form the basis for this determination.

References

Hendrickson MR, Kempson RL . Normal histology of the uterus and fallopian tubes. In: Sternberg SS (ed). Histology for Pathologists, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, 1997, pp 879–927.

Fu YS . Development, anatomy, and histology of the lower female genital tract. In: Fu YS (ed). Pathology of the Uterine Cervix, Vagina and Vulva, 2nd edn. Saunders: Philadelphia, 2002, pp 24–56.

Nucci MR, Crum CP . Redefining early cervical neoplasia: recent progress. Adv Anat Pathol 2007;14:1–10.

Al-Saleh W, Delvenne P, Greimers R, et al. Assessment of Ki-67 antigen immunostaining in squamous intraepithelial lesions of the uterine cervix. Correlation with the histologic grade and human papillomavirus type. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;104:154–160.

Kruse AJ, Baak JP, de Bruin PC, et al. Ki-67 immunostaining in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): a sensitive marker for grading. J Pathol 2001;193:48–54.

Heatley MK . What is the value of proliferation markers in the normal and neoplastic cervix? Histol Histopathol 1998;13:249–254.

McCluggage WG, Buhidma M, Tang L, et al. Monoclonal antibody MIB1 in the assessment of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:131–136.

Shurbaji MS, Brooks SK, Thurmond TS . Proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunoreactivity in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and benign cervical epithelium. Am J Clin Pathol 1993;100:22–26.

Pirog EC, Baergen RN, Soslow RA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cervical low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions is improved with MIB-1 immunostaining. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:70–75.

Chi CH, Rubio CA, Lagerlof B . The frequency and distribution of mitotic figures in dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Cancer 1977;39:1218–1223.

Tanaka T . Proliferative activity in dysplasia, carcinoma in situ and microinvasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Pathol Res Pract 1986;181:531–539.

Mushika M, Miwa T, Suzuoki Y, et al. Detection of proliferative cells in dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix by monoclonal antibody against DNA polymerase alpha. Cancer 1988;61:1182–1186.

Kobayashi I, Matsuo K, Ishibashi Y, et al. The proliferative activity in dysplasia and carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix analyzed by proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunostaining and silver-binding argyrophilic nucleolar organizer region staining. Hum Pathol 1994;25:198–202.

Xue Y, Feng Y, Zhu G, et al. Proliferative activity in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 1999;112:373–375.

Popiolek D, Ventura K, Mittal K . Distinction of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions from high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions based on quantitative analysis of proliferative activity. Oncol Rep 2004;11:687–691.

Van Leeuwen AM, Pieters WJ, Hollema H, et al. Atypical mitotic figures and the mitotic index in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Virchows Arch 1995;427:139–144.

Ward BE, Saleh AM, Williams JV, et al. Papillary immature metaplasia of the cervix: a distinct subset of exophytic cervical condyloma associated with HPV-6/11 nucleic acids. Mod Pathol 1992;5:391–395.

Egan AJ, Russell P . Transitional (urothelial) cell metaplasia of the uterine cervix: morphological assessment of 31 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1997;16:89–98.

Weir MM, Bell DA, Young RH . Transitional cell metaplasia of the uterine cervix and vagina: an underrecognized lesion that may be confused with high-grade dysplasia. A report of 59 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:510–517.

Gould SF, Shannon JM, Cunha GR . The autoradiographic demonstration of estrogen binding in normal human cervix and vagina during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the menopause. Am J Anat 1983;168:229–238.

Scharl A, Vierbuchen M, Graupner J, et al. Immunohistochemical study of distribution of estrogen receptors in corpus and cervix uteri. Arch Gynecol Obstet 1988;241:221–233.

Ciocca DR, Puy LA, Lo Castro G . Localization of an estrogen-responsive protein in the human cervix during menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause and in abnormal cervical epithelia without atypia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;155:1090–1096.

Kanai M, Shiozawa T, Xin L, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of sex steroid receptors, cyclins, and cyclin-dependent kinases in the normal and neoplastic squamous epithelia of the uterine cervix. Cancer 1998;82:1709–1719.

Cano A, Serra V, Rivera J, et al. Expression of estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and an estrogen receptor-associated protein in the human cervix during the menstrual cycle and menopause. Fertil Steril 1990;54:1058–1064.

Mosny DS, Herholz J, Degen W, et al. Immunohistochemical investigations of steroid receptors in normal and neoplastic squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol 1989;35:373–377.

Remoue F, Jacobs N, Miot V, et al. High intraepithelial expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the transformation zone of the uterine cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1660–1665.

Kupryjanczyk J, Moller P . Estrogen receptor distribution in the normal and pathologically changed human cervix uteri: an immunohistochemical study with use of monoclonal anti-ER antibody. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1988;7:75–85.

Konishi I, Fujii S, Nonogaki H, et al. Imunohistochemical analysis of estrogen receptors, progestrone receptors, Ki-67 antigen, and human papillomavirus DNA in normal and neoplastic epithelium of the uterine cervix. Cancer 1991;68:1340–1350.

Scully RE, Bonfiglio TA, Kurman RJ, et al. Histological Typing of Female Genital Tract Tumours (International Histological Classification of Tumours), 2nd edn. Springer Verlag, 1994.

Kurman RJ, Norris HJ, Wilkinson E . Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 3rd series, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Fascicle Washington, DC, 1992.

Baak JR . Mitosis counting in tumors. Hum Pathol 1990;21:683–685.

Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J . Dating the endometrial biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975;122:262–263.

Pahuja S, Choudhury M, Gupta U . Ki-67 labelling as a proliferation marker in pre-invasive squamous epithelial lesions of cervix. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2003;46:402–404.

Kalof AN, Cooper K . p16INK4a immunoexpression: surrogate marker of high-risk HPV and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Adv Anat Pathol 2006;13:190–194.

Richart RM . Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Pathol Annu 1973;8:301–328.

Arends MJ, Buckley CH, Wells M . Aetiology, pathogenesis, and pathology of cervical neoplasia. J Clin Pathol 1998;51:96–103.

Wells M, Ostor AG, Crum CP, et al. Epithelial tumours. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2003, pp 260–279.

Herrington CS . Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia. II. Interaction of HPV with other factors. J Clin Pathol 1995;48:1–6.

Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, et al. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:244–265.

Stoler MH . Human papillomaviruses and cervical neoplasia: a model for carcinogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:16–28.

Evans MF, Cooper K . Human papillomavirus integration: detection by in situ hybridization and potential clinical application. J Pathol 2004;202:1–4.

Ostor AG . Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:186–192.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure

The opinions and/or assertions contained herein are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as official, or as representing the views of the United States Government or any of its subsidiaries.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fadare, O., Yi, X., Liang, S. et al. Variations of mitotic index in normal and dysplastic squamous epithelium of the uterine cervix as a function of endometrial maturation. Mod Pathol 20, 1000–1008 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800935

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800935

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Präkanzerosen der Cervix uteri

Der Pathologe (2011)