Abstract

We developed a novel polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based method to analyze simultaneously the relative expression of two genes in a single PCR reaction. The method, relational PCR (R-PCR), utilizes special PCR primers that enable a PCR reaction to be converted from a standard uniplex reaction to a multiplex reaction in which all products are dependent on the same reaction components for amplification. We show that the quantitative ability of R-PCR is unaffected by sample nucleic acid input concentration over a range of 25-fold (30 to 750 ng of total RNA) and demonstrate excellent interexperimental reproducibility. We used R-PCR to analyze estrogen receptor gene expression in a series of invasive breast carcinomas, and our results show an excellent correlation between estrogen receptor mRNA expression and protein product accumulation determined by standard immunocytochemistry on paraffin sections.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Methods to assess gene expression in small biologic samples fall into two broad categories. First are high throughput cDNA arraying technologies in which small fragments of cDNA or oligonucleotides are placed on a solid support and hybridized with total cDNA from a tissue of interest and the level of hybridization is quantified (see McKenzie et al. [1] for a review). The second category encompasses polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methodologies including competitive reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) in which exogenous DNA or RNA is added to a PCR reaction and TaqMan (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) assays (1, 2).

cDNA array technologies allow the simultaneous analysis of the expression of thousands of genes. This becomes advantageous when one wants to study gene expression in a limited number of samples (e.g., compare mRNA expression between an experimental tissue/cell treatment and control). However, it is less useful in comparing gene expression in large numbers of biologic samples. In addition, the technology requires expensive equipment and reagents, making the technology unavailable to many researchers.

Competitive PCR methods assess the expression of one or a few genes in potentially large numbers of biologic samples. Competitive PCR reactions add RNA or cDNA competitor fragments that contain sequences complementary to the primers used to amplify the gene of interest to the PCR reaction. The exogenous control is engineered so that its PCR product is different in size from the endogenous gene product or contains a unique sequence facilitating its identification on agarose gels or by Southern blot hybridization, respectively. The exogenous control can be a subtle variant of the endogenous gene (e.g., containing a small deletion), so the amplification efficiency of the endogenous and competitive control fragments is similar, or the internal sequence can be completely different. Because the endogenous gene and competitive fragment compete for PCR reaction components (including primers), the relative amount of endogenous gene and competitive control products synthesized during the PCR reaction is proportional to the initial relative concentration of each template.

Analysis of gene expression in human tissues is complicated by the heterogeneous cellular composition of human tissue specimens. For example, the relative proportion of carcinoma cells in breast tumor tissue specimens varies widely. Some invasive carcinomas exhibit abundant tumor cells, whereas other cancers contain limited numbers of tumor cells and more stromal or reactive cells. Gene expression in these tissues must be normalized to the proportion of cells expressing the gene of interest. Therefore, accurate assessment of gene expression in human tissues with the use of traditional competitive PCR methods requires that the expression of two genes (the gene of interest and a cell-specific gene) be determined independently. As a result, costs are increased and throughput is decreased.

In most PCR-based gene expression analyses, absolute quantification of gene expression in tissues and cell lines is not required. Rather, gene expression in various disease states or cell types is compared with a control tissue or cell type. For example, an investigator may wish to compare gene expression in malignant tissue versus benign tissue and determine which tissues over- or underexpress the gene of interest. In these cases, the absolute copy number of mRNAs is not of prime importance; only the relative amounts expressed in each tissue needs to be assessed.

We describe a PCR-based method, relational PCR (R-PCR), that overcomes many of the difficulties of competitive RT-PCR. We show that converting the PCR reaction from a uniplex reaction to a competitive multiplex reaction while cycling eliminates the need to synthesize a competitive control and enables us to assess the relative expression of the gene of interest and a reference gene simultaneously. We also demonstrate that R-PCR gives equivalent results over a 25-fold range of total RNA sample concentration and use R-PCR to determine successfully the estrogen receptor (ER) status in invasive human breast cancers using a one-tube RT-PCR system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue and RNA Isolation

Breast carcinoma tissue specimens were obtained from surgical specimens submitted to the Pathology Department for routine examination for breast disease and stored in our liquid nitrogen tumor bank until use. Total RNA was isolated from all specimens using the RNeasy Total RNA Isolation System (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

R-PCR Experimental Procedures

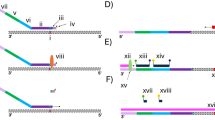

All one-tube RT-PCR assays used total RNA as a template. Each reaction contained 9 pmol of each ER gene-specific primer, 20 pmol of each cytokeratin 19 (CK19) gene-specific primer, and 40 pmol of the universal primer (Fig. 1). We used the Titan One Step PCR kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) for all R-PCR assays. The R-PCR amplification reactions consisted of a reverse transcription phase (54° C × 30 min) and an amplification phase (35 cycles [94° C × 15 seconds, 54° C × 10 seconds, 72° C × 15 seconds] followed by a 10-min hold at 72° C). Reaction products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel (140 V × 30 min), and the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using an EagleEye Gel Documentation System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). One RNA sample (see Fig. 2A) was quantified using a DU Series 650 Spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). The expected size of the ER and CK19 product bands are 198 bp and 278 bp, respectively.

PCR amplification of ER and CK19 in human tissues is reproducible and independent of starting nucleic acid concentration. A, ER and CK19 were PCR amplified from 30 ng (Lane 2), 300 ng (Lane 3), or 750 ng (Lane 4) total RNA. Total RNA was isolated from an invasive breast carcinoma. Lane 1, 1 Kb Plus Ladder. B, ER and CK19 were PCR amplified in five separate reactions (Lanes 2–6) using the same RNA. Lane 1, 1 Kb Plus Ladder.

Generation of ER and CK19 cDNA Fragments and Quantification of cDNA

ER and CK19 cDNA fragments (used for results presented in Fig. 3) were amplified for 35 cycles using the Titan One-Tube RT-PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The reactions used 1 μg of total RNA isolated from a breast carcinoma tissue specimen as template and primers (10 μm each) to amplify either

ER: (5′-TCGTTCCCTTGGATCTGATG-3′ and 5′-TGTGCTCTTTTTCCAGGTGG-3′)

or CK19:(5′-CAGATGAGCAGGTCCGAGGTTACTGAC-3′ and 5′ATGTCCATGAGCCGCTGGTACTCC-3′).

The reverse transcription phase of the RT-PCR reaction consisted of a hold at 54° C for 30 min. The amplification phase consisted of 35 cycles (94° C × 15 seconds, 54° C × 10 seconds, 72° C × 15 seconds). All PCR reactions were performed using a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 thermocycler (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Reaction products were purified using QIAquick PCR Spin Columns (Qiagen) and quantified using a DU Series 650 Spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments). The cDNA fragments were amplified in R-PCR experiments using Amplitaq Gold (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems) for 35 cycles (94° C × 15 seconds, 54° C × 10 seconds, 72° C × 15 seconds) followed by a single 10-min hold at 72° C. Reaction products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel (140 V × 30 min), and the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using an EagleEye Gel Documentation System (Stratagene).

RESULTS

Relational PCR Converts Uniplex PCR Reactions into Multiplex Competitive PCR Reactions

R-PCR requires five PCR primers: two primer pairs to amplify the gene of interest and a reference gene, and a universal primer (Fig. 1). Each gene-specific primer is 40 to 50 bp in length and consists of a 3′ gene-specific region and a 5′ universal primer sequence. The universal primer by itself does not amplify any RNA from human tissues (data not shown). Consequently, amplification of both the gene of interest and the reference gene during initial cycles of the R-PCR reaction is dependent on the gene-specific primers. The PCR products that accumulate during these cycles, however, can be further amplified by the universal primer, because the gene-specific primers that become incorporated into products contain the universal amplification primer sequence. As the universal primer sequence becomes incorporated into PCR products, the PCR reaction converts from a uniplex reaction to a standard competitive multiplex reaction in which the genes are competing for the same reaction components.

After the R-PCR reaction is complete, products are then subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and expression is estimated by visual inspection of the ethidium bromide–stained gels. The relative band intensity of the gene of interest and reference gene product in each sample is assessed and compared with the relative band intensity in a control sample. If the product band of the gene of interest is more intense than the reference gene in an experimental tissue compared with a control tissue, then the gene of interest is more highly expressed in the experimental tissue than the control tissue. Likewise, if the product band of the gene of interest is less intense than the reference gene in another experimental tissue compared with the control tissue, then the gene of interest in this experimental tissue is expressed at a lower level than the control tissue. The band intensity of the gene of interest product is not directly comparable between samples because the total amount of amplification in each reaction is dependent on the concentration of the nucleic acid sample and the amplification efficiency.

Before R-PCR can be used to quantify gene expression, it is necessary to determine empirically the amount of gene-specific primer pairs to use in the PCR reaction. This step is required because the reference gene may be expressed at significantly higher or lower levels than the gene of interest. We have successfully reduced the amplification efficiency of a dominant PCR product by adding to the PCR reaction either 3′ phosphorylated gene-specific primers that are unable to be extended by DNA polymerases or by simply reducing the amount of primers added to amplify the dominant gene. To reduce costs, we use the latter method because it does not require the purchase of additional primers.

To establish the appropriate primer concentrations for genes that are expressed at widely varying levels, we use RNA from biologic samples that express the gene of interest at either the highest or the lowest expected level. If we use RNA from a sample that expresses the gene of interest at high levels, then we determine the primer concentrations that produce an intense gene of interest product band and a barely visible reference gene product band. If the sample expresses the gene of interest at low levels, then we use primer concentrations that produce a predominant reference gene product band. Once the concentration of primers to be used in R-PCR experiments is established, all subsequent R-PCR reactions use the same amount of primers.

R-PCR Accurately Quantifies the Relative Amount of Two Genes over a Broad Range of Input Concentrations

To demonstrate the ability of R-PCR to perform accurate DNA quantification, we generated short cDNA fragments of the human ER and CK19 genes so we could accurately vary the initial concentration of each gene fragment in our experiment. We then performed a series of R-PCR reactions in which the relative amount of ER template was sequentially increased 2-fold (Fig. 3). As the amount of ER template was increased relative to CK19, ER product production increased relative to CK19. The data shown in Figure 3 demonstrates that a 2- to 4-fold difference in the initial amount of ER template is easily identifiable across the 256-fold range of relative dilutions used in this experiment. These results are consistent with results that we have obtained using other types of competitive PCR assays (data not shown).

R-PCR Produces Reproducible Results over a Wide Range of Sample Concentrations

Most competitive PCR assays require that the amount of RNA added to each PCR reaction be rigorously determined to compare results from different biologic specimens. This limits the ease with which competitive PCR can be performed and limits its utility in assays that depend on high throughput. We reasoned that because R-PCR quantifies the expression of one gene relative to a reference gene, the R-PCR assay might have the significant benefit of being independent of the initial sample concentration. To test this hypothesis, we amplified 30, 300, or 750 ng of total RNA isolated from a ER-positive human invasive breast carcinoma in three separate one-tube R-PCR reactions and electrophoresed the products on an agarose gel (Fig. 2A). The ratio of ER and CK19 product bands in each lane appears equivalent, demonstrating that R-PCR gives similar results over a wide range (at least 25-fold) of input template concentration. The standard RNA quantification step performed before most competitive PCR reactions is therefore rendered unnecessary in R-PCR experiments.

Next, we determined the reproducibility of the R-PCR assay. We made a master mix of all one-tube R-PCR reaction components, put aliquots into five separate tubes, and amplified ER and CK19 for 35 cycles using RNA isolated from a ER-positive tumor as template. The relative concentration of ER and CK19 PCR products was remarkably uniform in all three reactions (Fig. 2B). Moreover, because the results presented in Figure 2 were obtained using RNA from the same ER-positive tumor, the results are directly comparable and estimate the level of interexperimental variability. Again, the results from both experiments are similar. Together, these results demonstrate that R-PCR is reproducible and quantifies gene expression over a wide range of template nucleic acid concentrations.

R-PCR Accurately Determines ER Status in Human Breast Carcinomas

We used R-PCR to determine the level of ER expression relative to CK19 in a series of 20 invasive breast carcinomas (8 ER negative and 12 ER positive) and correlated the results with ER status determined by immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections. We used CK19, which is predominantly expressed in breast epithelium (including breast tumor cells), as the reference gene to normalize ER expression relative to the number of tumor cells in the sample tissue. Although CK19 is also present in benign breast epithelium, the tissues used in this study were histologically verified to contain few benign breast ductules and/or lobules. The approximate percentage of tumor cells in a surgical specimen could be estimated by histologic analyses, but normalizing gene expression relative to CK19 is easier and may be more accurate. Total RNA was isolated from tumor tissue specimens, and 1μ of 40μ of each RNA sample was added to a one-tube R-PCR reaction without prior determination of RNA concentration. After 35 cycles, PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and the gels were visually inspected to assess the relative expression of ER and CK19.

All eight tumors determined to be ER negative by ER immunohistochemistry were correctly identified as being ER negative by R-PCR, and 11 of 12 tumors that were ER positive by immunohistochemistry were positive by R-PCR (Fig. 4). Each of the ER-negative tumors have prominent CK19 product bands and relatively faint or absent ER bands (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the CK19 and ER product bands are nearly equal in intensity in the ER-positive tumors (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that ER-positive tumors have significantly more ER RNA than do ER-negative tumors.

The correlation rate of 95% in our sample compares favorably with the correlation rate (80 to 85%) of ER level determination by immunohistochemistry and biochemical ligand-binding assays (DCCA) (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

DISCUSSION

Recent advances in molecular techniques have enabled unprecedented numbers of differentially expressed genes to be identified, creating the need for improved PCR-based methods that rapidly assess gene expression nonradioactively in small clinically available biologic specimens. Two types of PCR assays are currently used to analyze gene expression when biologic material is limiting or when high throughput is required: TaqMan (2) and competitive PCR assays (12, 13, 14). Real-time PCR (TaqMan) assays use the fluorogenic 5′ nuclease assay to determine exact copy number and provides excellent results with minimal hands-on time. Unfortunately, both the equipment and labeled primers needed to perform TaqMan assays are still expensive. In contrast, competitive PCR assays that use internal controls of unrelated sequence (PCR MIMICS) do not provide exact RNA copy number but generate sufficient quantification for most experimental systems and require no specialized equipment or labeled primers. Competitive PCR does, however, require synthesis of the competitive fragment, and comparison of gene expression between biologic specimens requires careful quantification and normalization of RNA or cDNA starting material.

To enhance the ease with which competitive PCR assays are performed, we developed R-PCR that converts a normally uniplex PCR reaction into a multiplex competitive PCR reaction. R-PCR can quantify cDNA fragments using standard PCR assays or quantify mRNA directly using a one-tube RT-PCR reaction system. R-PCR does not require prior determination of sample concentration or the separate synthesis of an independent exogenous competitive nucleic acid standard. If the reference gene is cell-type specific and is uniformly expressed in those cells, then the gene of interest is normalized relative to the cell type. This is especially useful for tissue samples in which the relative ratio of cell types varies between specimens. For gene expression analyses in human tissue culture cells, G3PDH or ribosomal RNA can reliably serve as a reference gene. Because R-PCR analyzes gene expression relative to a reference gene, R-PCR can potentially determine the expression of multiple genes in a single tube. Indeed, we successfully used R-PCR to examine the expression of two genes relative to human β-actin in human breast cancer (data not shown), and we expect that more genes can be added to the assay.

As with all multiplex PCR reactions, the R-PCR primers must be chosen carefully to reduce the likelihood of nonspecific interactions. The gene-specific primers should not interact with each other or with the universal amplification primer. In general, smaller PCR primers and products are less likely to interact with each other than are longer ones, and our experience suggests that software programs are especially good at finding suitable primer combinations. We have also successfully used numerous different universal amplification primer sequences (data not shown), so it should be possible to develop unique and specific primer combinations for virtually any gene.

The level of ER expression in invasive human breast carcinomas is routinely determined because ER-positive tumors are more likely to respond to endocrine therapy than are ER-negative tumors and have a better prognosis (4, 8, 10). Historically, ER expression was determined using ligand-binding assays. In the past few years, immunohistochemical methods have supplanted the biochemical methods because they are easier to perform. Numerous studies show approximately an 80 to 90% correlation between the ligand-binding assays and immunohistochemistry (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Disagreements in the ER status of some invasive breast carcinomas using these methodologies may be due to the inability of ligand-binding assays to account for the heterogeneous cellular composition of breast tumor specimens. Using our R-PCR assay, which used CK19 to normalize ER expression relative to tumor epithelium, we obtained a much higher level of correlation with the immunohistochemical method (95%). The high correlation between these methods demonstrates that R-PCR is a viable alternative or adjunct to immunohistochemical methods for the analysis of ER status in human breast cancer.

References

McKenzie SE, Mansfield E, Rappaport E, Surrey S, Fortina P . Parallel molecular genetic analysis. Eur J Hum Genet 1998; 6 (5): 417–429.

Heid CA, Stevens J, Livak KJ, Williams PM . Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res 1996; 6 (10): 986–994.

Alberts SR, Ingle JN, Roche PR, Cha SS, Wold LE, Farr GH Jr, et al. Comparison of estrogen receptor determinations by a biochemical ligand-binding assay and immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibody ER1D5 in females with lymph node positive breast carcinoma entered on two prospective clinical trials. Cancer 1996; 78 (4): 764–772.

Molino A, Micciolo R, Turazza M, Bonetti F, Piubello Q, Corgnati A, et al. Prognostic significance of estrogen receptors in 405 primary breast cancers: a comparison of immunohistochemical and biochemical methods. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997; 45 (3): 241–249.

Molino A, Micciolo R, Turazza M, Bonetti F, Piubello Q, Corgnati A, et al. Estrogen receptors in 699 primary breast cancers: a comparison of immunohistochemical and biochemical methods. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1995; 34 (3): 221–228.

Biesterfeld S, Schroder W, Steinhagen G, Koch R, Veuskens U, Schmitz FJ, et al. Simultaneous immunohistochemical and biochemical hormone receptor assessment in breast cancer provides complementary prognostic information. Anticancer Res 1997; 17 (6D): 4723–4729.

Katoh AK, Stemmler N, Specht S, D'Amico F . Immunoperoxidase staining for estrogen and progesterone receptors in archival formalin fixed, paraffin embedded breast carcinomas after microwave antigen retrieval. Biotech Histochem 1997; 72 (6): 291–298.

Blomqvist C, von Boguslawski K, Stenman UH, Maenpaa H, von Smitten K, Nordling S . Long-term prognostic impact of immunohistochemical estrogen receptor determinations compared with biochemical receptor determination in primary breast cancer. Acta Oncol 1997; 36 (5): 530–532.

Huang A, Pettigrew NM, Watson PH . Immunohistochemical assay for oestrogen receptors in paraffin wax sections of breast carcinoma using a new monoclonal antibody. J Pathol 1996; 180 (2): 223–227.

Pertschuk LP, Kim YD, Axiotis CA, Braverman AS, Carter AC, Eisenberg KB, et al. Estrogen receptor immunocytochemistry: the promise and the perils. J Cell Biochem 1994; 19 (Suppl): 134–137.

Kerner H, Zilberman M, Israeli E, Lichtig C . A comparative study of radioligand (DCC) and modified immunoperoxidase anti-estrogen receptor techniques in breast carcinoma. Israel J Med Sci 1994; 30 (7): 506–509.

Gilliland G, Perrin S, Blanchard K, Bunn HF . Analysis of cytokine mRNA and DNA: detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87 (7): 2725–2729.

Becker-Andre M, Hahlbrock K . Absolute mRNA quantification using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR): a novel approach by a PCR aided transcript titration assay (PATTY). Nucleic Acids Res 1989; 17 (22): 9437–9446.

Wang AM, Doyle MV, Mark DF . Quantitation of mRNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989; 86 (24): 9717–9721.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. S. Pochebit, R. Mosher, and B. Stringer for providing specimens used in this work and for help in manuscript preparation. This work was generously supported by grants from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Breast Cancer Research Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shepard, S., Cooper, A. Assessing the Expression of Two Genes Simultaneously in Surgical Specimens Using Polymerase Chain Reaction. Mod Pathol 13, 401–406 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880068

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880068