Abstract

Neoplasm of the vulva is a rare malignancy accounting for <5% of all female genital-tract cancer. However, in recent years the incidence of vulva intraepithelial neoplasia, known to serve as a precursor to carcinoma, has increased in young women generating considerable interest in its pathogenesis. Genetic changes at the molecular level in precursor or invasive vulvar tumors are not well investigated, and DNA copy number changes have not been reported until now. We used comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) to analyze genetic alterations in 10 primary invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva. Chromosomal aberrations were identified in 8/10 cases. The most frequent chromosomal losses were 4p13–pter (five cases), 3p (four cases), and 5q (two cases), and less frequent losses were detected at 6q, 11q, and 13q (one case each). The most frequent chromosomal gains were 3q (four cases) and 8p (three cases), and less frequent gains were found in 9p, 14, 17, and 20q (one case each). The pattern of chromosomal imbalance in vulvar cancer detected by CGH was revealed to be very similar to that in cervical cancers, despite regional differences in their prevalence. These results suggest that the pathogenic pathways in vulvar and cervical carcinomas may be similar and that the genetic background may be common to these two squamous cell carcinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of the vulva is a relatively uncommon malignancy in women, with an incidence of approximately 1.5/100,000 a year worldwide. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) has long been considered a disease of older women, and its etiology has largely been unknown. However, a number of recent epidemiologic studies have linked VSCC to well-known risk factors in cervical carcinoma, including multiple sexual partners, a history of venereal warts, and smoking (1). Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection has also been suggested as a possible causative agent, but its relationship to VSCC seems to be less strong than in cervical cancer because of its lower incidence.

Functional inactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene through mutation or deletion is almost a universal step in the development or progression of human tumors (2). Many reports show that alterations in p53 may affect the carcinogenesis of the vulva more than that of the cervix, in which HPV infection predominates as a causative agent (3, 4, 5, 6). More recent data suggest that the overexpression of p53 protein is a late event and that the gene is a useful marker to predict lymph node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma (7, 8, 9, 10).

Until recently, most conventional cytogenetic studies have failed to identify any landmark chromosomal aberrations associated with cervical carcinoma. There have been a few reports on the cytogenetic analysis of vulvar tumors, which describe chromosomal alterations in VSCC, such as rearrangement of 11p as the sole abnormality (11). A variety of karyotypic abnormalities in VSCC have been reported, including both losses (3p, 5q, 8p, 10q, 15q, 18q, 19p, 22q, Xp, and others) and gains (3q) (7, 12, 13). However, no specific, consistent chromosomal abnormalities have been found until now.

Genetic changes at the molecular level are less well known than cytogenetic aberrations. Some loci of chromosomal losses and gains in VSCC have been confirmed using the LOH (loss of heterozygosity) study. Pinto et al. (13) observed allelic losses in chromosome arms 2q, 3p, 5q, 8p, 8q, 17p, and 21q.

Recently, the comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) technique has been widely applied to analysis of chromosomal imbalances (14, 15). In some reports, CGH techniques have demonstrated that one of the most consistent chromosomal abnormalities that marks the transition of carcinoma in situ (CIS) to invasive carcinoma of cervix is the gain of specific chromosome 3q sequences (16). Furthermore, a variety of loci in many chromosomes have been shown to be altered in cervical carcinoma (17, 18, 19). However, no CGH findings in VSCC have been reported so far.

We performed CGH analysis on vulvar carcinoma and discuss here these findings comparing them with previous results reported by others on cervical carcinoma and with conventional cytogenetic data of vulvar carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

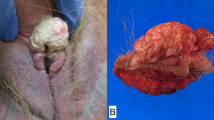

Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were obtained after surgery from 10 patients with primary VSCC. The histological diagnoses were performed in the Department of Pathology, ASAN Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea). Table 1 shows clinical data on each of the cases.

Tumor cells were collected after removal of stroma by scraping with a clean scalpel from three unstained slide sections of 10-μm thickness. The slides were deparaffinized in xylene (three times, for 5 min each) and 100% ethanol (twice, for 5 min each). The tumor cells were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing digestion buffer, and high–molecular weight DNA was extracted as previously described (20).

Comparative Genomic Hybridization

CGH was performed as described elsewhere (21). Normal DNA was extracted from peripheral blood of healthy donors and labeled with Texas-Red-dCTP and Texas-Red-dUTP (DuPont, Boston, MA) in a standard nick-translation reaction. The tumor DNA was labeled with a mixture of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dCTP and FITC-dUTP (DuPont). Equal amounts of labeled tumor and reference DNA were mixed with 20-μg of unlabeled human Cot-1 DNA (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) in 10-μL of hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2 × SSC [1 × SSC: 0.15 m sodium chloride/0.015 m sodium citrate, pH 7]) and hybridized onto normal metaphase slides. Before hybridization, the DNA was denatured for 5 minutes at 75°C, and the metaphase slides were treated in 70, 80, and 100% ethanol series and denatured at 65°C for 2 minutes in a formamide solution (70% formamide/2 × SSC). Hybridization was performed in a moisture chamber at 37°C for 48 hours, and washing was performed in 50% formamide/2 × SSC and twice in 2 × SSC. Then the slides were mounted with an antifading medium containing a counterstain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and analyzed using the ISIS CGH analysis system (MetaSystems GmbH, Altlussheim, Germany). The average-ratio profile was calculated as a mean value obtained from 10 to 15 metaphases. Both homologues of good-quality chromosomes with strong uniform hybridization were selected for analysis. Chromosomal regions were interpreted as overrepresented (gained) when the green-to-red ratio was >1.17 (1.5 cutoff value for high-level amplifications) and as underrepresented (lost) when the ratio was <0.85 (Fig. 2). Confidence limits of 99% with 1% error probability were used to confirm the interpretation. To confirm the CGH results, additional hybridization experiments were performed on some specimens. A positive-control DNA with known chromosomal aberrations and a negative-control DNA were extracted from paraffin-embedded ovarian carcinoma material.

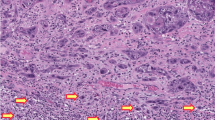

Selected comparative genomic hybridization profiles of the most frequent DNA copy number gains (3q and 8q) and losses (3p and 4p) in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (Case 9). The number of analyzed chromosomes is shown after the slash. The line in the middle of the profile indicates the green-to-red ratio value of 1, the lines to the left and right indicate threshold values of 0.85 (loss) and 1.17 (gain), respectively.

RESULTS

DNA copy number changes were found in 8 of the 10 tumors (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

The most frequent loss was 4p13–pter (5/10; Fig. 2), and losses in 3p, 5q, 6q, and 13q were less frequent. The most frequent gains were 3q (4/10) and 8q (3/10), whereas gains in 9p, 14, 17, and 20q were found in only one patient (Case 9). Case 9, which showed moderate histological differentiation, had a high number of changes (12), including losses in 4p, 3p, 3q, 5q, 11q, 13q, 14, 17, and 20, whereas Cases 5–8, with well-differentiated tumors, showed one to three copy number changes per sample. Gain in 3q and losses in 3p and 4p were concomitant in four cases (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

We found that the most frequent DNA copy number changes in VSCC are loss of 4p13–pter and gain of 3q. So far, no CGH findings have been reported in VSCC, and differences between our results and previously published cytogenetic data in VSCC are considerable. Previous chromosome banding and LOH analyses have not revealed changes in 4p, but alterations have been found in 3p. For chromosome 4, the discrepancy between the results may be explained by methodological reasons. One explanation for the difference between LOH analysis results may be the scarcity of markers for 4p. Interestingly, the pattern of chromosomal imbalance found by CGH in vulvar carcinoma is very similar to that in cervical carcinoma (16, 19, 22).

No cancer genes have been assigned to 4p. However, the recurrent loss of 4p we found and similar findings by others in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (18, 23) suggest that this chromosomal area may harbor a tumor suppressor gene.

In cervical cancer, Heselmeyer et al. (16) suggested that a deletion of 3p could be the result of isochromosome formation with retainment of i(3q) and that losses of 3p isochromosome formation may be one step toward invasiveness (22). We found concomitant loss of 3p and gain in 3q, which agrees with the isochromosome formation.

The long arm of chromosome 3 contains numerous potential cancer genes, such as MME, IL12A, BCHE, and KNG, and the human telomerase RNA gene (HTR) has recently been mapped to 3q26.3 (14, 24). Soder et al. (24) found increased copy numbers of the HTR locus in 97% of cervical carcinomas.

The regions of the TSG and FRA3B genes in 3p have been suggested to contain HPV integration sites (25, 26). Deletion at 3p and gain of 3q suggested correlation with HPV infection in cervical and anal cancer. However, in fallopian tube carcinoma, 3q gain was not associated with HPV DNA (16, 17). The association of 3p and 4p losses with HPV infection in cervical carcinoma has been, interestingly enough, reported in HPV-positive cervical carcinoma (16) and in an HPV-immortalized keratinocyte cell line (27). Incidence of HPV positivity has been reported at rates between 9 and 83% in vulvar carcinoma (28, 29). The great variation results most probably from the methods used. We were able to perform only one successful analysis on our patients (Case 3 was positive).

In conclusion, we observed that loss of 4p13–pter, and concomitant loss of 3p and gain in 3q, are the most frequent genetic alterations in invasive VSCC and that the pattern of the alterations is very similar to that seen in cervical carcinoma. These results suggest that the pathogenic pathways in vulvar and cervical carcinomas may be similar and that the genetic background may be common to these squamous cell carcinomas. The next tasks indicated by our CGH findings are identification of candidate genes in the lost and gained chromosomal regions and investigation of possible HPV virus integration in these areas.

References

Crum CP . Carcinoma of the vulva: Epidemiology and pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 448–454.

Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC . p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 1991; 253: 49–53.

Pilotti S, D’Amato L, Della Torre G, Donghi R, Longoni A, Giarola M, et al. Papillomavirus, p53 alteration, and primary carcinoma of the vulva. Diagn Mol Pathol 1995; 4: 239–248.

Sliutz G, Schmidt W, Tempfer C, Speiser P, Gitsch G, Eder S, et al. Detection of p53 point mutations in primary human vulva cancer by PCR and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. Gynecol Oncol 1997; 64: 93–98.

Ochiai T, Honda A, Morishima T, Sata T, Sakamoto H, Satoh K . Human papillomavirus types 16 and 39 in a vulval carcinoma occurring in a woman with Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 509–513.

Scheistroen M, Trope C, Pettersen EO, Nesland JM . p53 protein expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer 1999; 85: 1133–1138.

Teixeira MR, Kristensen GB, Abeler VM, Heim S . Karyotypic finding in tumors of the vulva and vagina. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999; 111: 87–91.

Lee YY, Wilczynski SP, Chumakov A, Chih D, Koeffler HP . Carcinoma of the vulva: HPV and p53 mutations. Oncogene 1994; 9: 1655–1659.

Kohlberger P, Kainz C, Breitenecker G, Gitsch G, Sliutz G, Kolbl H, et al. Prognostic value of immunohistochemically detected p53 expression in vulvar carcinoma. Cancer 1995; 76: 1786–1789.

Emanuels AG, Koudstaal J, Burger MP, Hollema H . In squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, overexpression of p53 is a late event and neither p53 nor mdm2 expression is a useful marker to predict lymph node metastases. Br J Cancer 1999; 80: 38–43.

Swanson GP, Dobin SM, Arber JM, Arber DA, Capen CV, Diaz JA . Chromosome 11 abnormalities in Bowen disease of the vulva. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1997; 93: 109–114.

Worsham MJ, Van Dyke DL, Grenman SE, Grenman R, Hopkins MP, Roberts JA, et al. Consistent chromosome abnormalities in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1991; 3: 420–432.

Pinto AP, Lin M-C, Mutter GL, Sun D, Villa LL, Crum CP . Allelic loss in human papillomavirus-positive and -negative vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol 1999; 1009–1015.

Knuutila S, Bjsrkqvist A-M, Autio K, Tarkkanen M, Wolf M, Monni O, et al. DNA copy number amplifications in human neoplasms. Review of comparative genomic hybridization studies. Am J Pathol 1998; 152: 1107–1123.

Knuutila S, Aalto Y, Autio K, Björkqvist A-M, El-Rifai W, Hemmer S, et al. DNA copy number losses in human neoplasms. Review. Am J Pathol 1999; 155: 683–694.

Heselmeyer K, Schröck E, du Manoir S, Blegen H, Shah K, Steinbeck R, et al. Gain of chromosome 3q defines the transition from severe dysplasia to invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 479–484.

Heselmeyer K, Hellström A-C, Blegen H, Schröck E, Silfverswärd C, Shah K, et al. Primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube: comparative genomic hybridization reveals high genetic instability and a specific, recurring pattern of chromosomal aberrations. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998; 17: 245–254.

Larson AA, Liao S-Y, Stanbridge EJ, Cavenee WK, Hampton GM . Genetic alterations accumulate during cervical tumorigenesis and indicate a common origin for multifocal lesions. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 4171–4176.

Dellas A, Torhorst J, Jiang F, Proffitt J, Schultheiss E, Holzgreve W, et al. Prognostic value of genomic alterations in invasive cervical squamous cell carcinoma of clinical stage IB detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3475–3479.

Abeln EC, Corver WE, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn NJ, Fleuren GJ, Cornelisse CJ . Molecular genetic analysis of flow-sorted ovarian tumour cells: Improved detection of loss of heterozygosity. Br J Cancer 1994; 70: 255–262.

El-Rifai W, Larramendy ML, Björkqvist A-M, Hemmer S, Knuutila S . Optimization of comparative genomic hybridization using fluorochrome conjugated to dCTP and dUTP nucleotides. Lab Invest 1997; 77: 699–700.

Kirchhoff M, Rose H, Petersen BL, Maahr J, Gerdes T, Lundsteen C, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization reveals a recurrent pattern of chromosomal aberrations in severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ of the cervix and in advanced-stage cervical carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1999; 24: 144–150.

Hampton GM, Larson AA, Baergen RN, Sommers RL, Kern S, Cavenee WK . Simultaneous assessment of loss of heterozygosity at multiple microsatellite loci using semi-automated fluorescence-based detection: Subregional mapping of chromosome 4 in cervical carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 6704–6709.

Soder AI, Hoare SF, Muir S, Going JJ, Parkinson EK, Keith WN . Amplification, increased dosage and in situ expression of the telomerase RNA gene in human cancer. Oncogene 1997; 14: 1013–1021.

Wistuba II, Montellano FD, Milchgrub S, Virmani AK, Behrens C, Chen H, et al. Deletions of chromosome 3p are frequent and early events in the pathogenesis of uterine cervical carcinoma. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 3154–3158.

Wilke CM, Hall BK, Hoge A, Paradee W, Smith DI, Glover TW . FRA3B extends over a broad region and contains a spontaneous HPV16 integration site: Direct evidence for the coincidence of viral integration sites and fragile sites. Hum Mol Genet 1996; 5: 187–195.

Solinas-Toldo S, Dürst MPL . Specific chromosomal imbalances in human papillomavirus-transfected cells during progression toward immortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 3854–3859.

Brandenberger AW, Rudlinger R, Hanggi W, Bersinger NA, Dreher E . Detection of human papillomavirus in vulvar carcinoma. A study by in situ hybridisation. Arch Gynecol Obstet 1992; 252: 31–35.

Park JS, Jones RW, McLean MR, Currie JL, Woodruff JD, Shah KV, et al. Possible etiologic heterogeneity of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. A correlation of pathologic characteristics with human papillomavirus detection by in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Cancer 1991; 67: 1599–1607.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jee, K., Kim, Y., Kim, K. et al. Loss in 3p and 4p and Gain of 3q Are Concomitant Aberrations in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Mod Pathol 14, 377–381 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880321

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880321

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sec62/Ki67 and p16/Ki67 dual-staining immunocytochemistry in vulvar cytology for the identification of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and vulvar cancer: a pilot study

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2019)

-

High-resolution genomic profiling of human papillomavirus-associated vulval neoplasia

British Journal of Cancer (2010)

-

Amplification of chromosome 5p correlates with increased expression of Skp2 in HPV-immortalized keratinocytes

Oncogene (2003)

-

Genetic aberrations detected by comparative genomic hybridisation in vulvar cancers

British Journal of Cancer (2002)