Abstract

The INK4a locus encodes two structurally unrelated tumor suppressor proteins, p16INK4a and p14ARF. Although the former is one of the most common targets for inactivation in human neoplasia, the frequency of p14ARF abrogation is not established. We have developed an immunohistochemical assay that allows the evaluation of p14ARF expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, using commercially available antibodies. p14ARF positive cells showed nuclear/nucleolar staining, which was absent in all cell lines and tumors with homozygous deletions of the INK4a gene. The assay was applied to 34 paraffin-embedded cell buttons, 30 non-small cell lung cancers and 28 pancreatic carcinomas, and the staining results were correlated with p16INK4a expression. Loss of p14ARF expression was common but less frequent than down-regulation of p16INK4a (53% versus 76% of all specimens). The p14ARF and p16INK4a expression pattern was concordant in 65 of 92 cases (71%). Significantly, 24 cases were p16INK4a−/p14ARF+, while the opposite staining pattern was observed in three cases, consistent with the notion that the two proteins have nonredundant functions. The immunohistochemical assay described here may facilitate studies on the prevalence and significance of aberrant p14ARF expression in human tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The INK4a gene on chromosome 9p21 is one of the most common targets for inactivation in human neoplasia. The gene is unusual in that it encodes two structurally unrelated proteins, p16INK4a and p14ARF, the human homologue of murine p19ARF. Two different first exons are spliced in different reading frames to common exon 2 (1). p16INK4a acts as a retinoblastoma protein (pRB) agonist by inhibiting the phosphorylation of pRB by activated cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (2). The principal methods of p16INK4a inactivation are homozygous deletion of the gene, promoter methylation of exon 1α, and intragenic mutation (3). The frequency of p16INK4a inactivation in human neoplasia rivals that of p53. We previously demonstrated that immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a sensitive and specific method of detecting the absence of functional p16INK4a in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors, whatever the underlying mechanism (4, 5). In contrast, p14ARF primarily acts as a p53 agonist by inhibiting the MDM2-mediated degradation of the latter (6, 7). p14ARF can also be inactivated by homozygous deletion, promoter hypermethylation, and, presumably, intragenic mutation, although no mutations selectively targeting exon 1β have been described (1). Promoter methylation of exons 1α and 1β appear to be independent events (8), and comparatively few data exist on the frequency of p14ARF inactivation in human neoplasia. An important reason for this relative lack of data may be the unavailability of an assay that would allow the evaluation of p14ARF expression in archival tissues. Here we describe such an assay, which utilizes commercially available reagents and which should be applicable in any immunohistochemical laboratory. We demonstrate the validity of our method and its application to paraffin-embedded cell lines and tumors, and we provide evidence that, at least in some human cancers, p14ARF abrogation, although important, may be less common than, and independent of, p16INK4a inactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Tissues

All lung cancer and mesothelioma cell lines (designated by the prefix “H”) were originally established at the National Cancer Institute—Navy Medical Oncology Branch (9). Breast cancer cell lines MCF–10A, SKBR3, BT474, T47D, MDA–MB–231, MDA–MB–361, and MDA–MB–468 were provided by the Imperial Cancer Research Fund Clare Hall Laboratories (London, UK). Colorectal carcinoma cell lines SW480, SW620, SW837, SW1463, RKO and DLD–1, and cell lines PC-3 and U2OS, as well as a nude mouse xenografts of cell lines H417 and H2009, had been used in previous immunohistochemical studies (4, 10, 11). The non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) were part of a cohort of well-characterized tumors from Australia (12). The pancreatic carcinomas were from the pathology files of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (5, 13). Normal breast, skin, colon, appendix, and tonsil and the phyllodes tumor were from the Department of Cellular Pathology at the John Radcliffe Hospital (Oxford, UK). The cell lines, xenograft, human tumors and normal tissues had been fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed, and embedded in paraffin using routine procedures.

Materials

Mouse monoclonal anti-p16INK4a antibody Ab-7 and monoclonal anti-p14ARF antibodies 14PO2 and 14P03, as well as polyclonal Ab-1 were obtained from LabVision/NeoMarkers (Fremont, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-p14ARF antibodies Ab-1/PC409 and ZF14 were obtained from Oncogene Research Products (via CN BioSciences, Nottingham, UK) and Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA), respectively. The Elite ABC detection kit was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Five μm thick paraffin sections were cut onto coated slides and stored at 4°C until used. The experiments were carried out in a Shandon Sequenza immunostainer. The immunohistochemical assay for detecting p16INK4a in fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues has been described in detail elsewhere (4, 5, 14). Briefly, after antigen retrieval in 0.1 m EDTA pH8.0 (20 minutes at 95 to 100° C), the sections were reacted with the anti-p16 monoclonal antibody at 1 μg/mL at 4°C overnight. Some of the p16INK4a staining data had been included in two earlier studies (5, 12). For p14ARF IHC, we initially tested all five antibodies (see Results). We chose to optimize reaction conditions for one of them, i.e., monoclonal antibody 14PO2. After dewaxing and rehydration, the endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched for 20 minutes with 0.3% H202 in methanol. The sections then underwent antigen retrieval in 0.01 m citrate buffer pH6.0 at 95 to 100° C for 20 minutes (cell blocks) or 40 minutes (tissues). After blocking with 1% horse serum for 20 minutes, the sections were reacted with primary antibody at 1 μg/mL (cell blocks) or 4 μg/mL (tissues) at 4°C overnight. The detection reactions for both p16INK4A and p14ARF followed the Vectastain Elite ABC protocol as suggested by the manufacturer. Diaminobenzidine (from Vector) with hematoxylin counterstain was used for color development. Negative antibody controls were stained under identical conditions. External positive controls for p14ARF included normal breast, colon, appendix, and tonsil, a phyllodes tumor, and nude mouse xenografts of lung cancer cell lines H417 and H2009. Several cell lines and tumors with known homozygous INK4a deletions served as external negative controls. A specimen was considered positive for p16INK4A or p14ARF if there was nuclear staining above any cytoplastic background; cytoplasmic staining itself was disregarded (5). If the cells of interest failed to show distinct nuclear reactivity, the specimen was considered negative for the respective protein. In tissue sections, admixed stromal, inflammatory, and normal epithelial cells served as positive internal controls.

RESULTS

Development of an Immunohistochemical Assay for p14ARF

In preliminary experiments, we tested five anti-p14ARF antibodies (three polyclonals and two monoclonals) obtained from three companies. After antigen retrieval in 0.1 m EDTA and primary incubation overnight at 1:400 (polyclonals) or 2 μg/mL (monoclonals), all five antibodies produced the expected nuclear staining pattern in positive controls. Because the monoclonal antibodies appeared to be more sensitive, we optimized the reaction conditions for one of them, 14PO2 from NeoMarkers. To validate the IHC assay, we used the positive and negative control specimens detailed in the Methods. Variables tested included primary antibody concentration, different antigen retrieval techniques, and different detection reactions, among others. We found it necessary to employ a longer antigen retrieval time and higher primary antibody concentration for archival tissues, compared with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cell buttons. In cells expressing p14ARF, the staining pattern was predominantly nuclear, sometimes with nucleolar accentuation, usually associated with some cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 1, A and C). In some tumors and cell lines, there was strong nucleolar staining. In many cell types, the staining intensity was less than for p16INK4a, but there seemed to be tissue specific variability. p14ARF levels appeared to be relatively high in the breast (Fig. 1A), but lower in other tissues. The protein was expressed by non-neoplastic epithelium of the breast, skin, tonsil, colon and appendix. Nuclear staining could also be detected in a subset of lymphocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells serving as convenient internal positive controls in tumor sections. No such staining was observed on negative antibody control stains. Cells devoid of p14ARF, e.g., those with a homozygous INK4a deletion, typically showed nonspecific cytoplasmic reactivity, but no nuclear staining above the background (Fig. 1B).

p14ARF staining patterns in archival tissues and cell lines. A, Strong nuclear and weak cytoplasmic reactivity in most epithelial and stromal cells of a phyllodes tumor stained for p14ARF. B, The tumor cells in a p14ARF negative NSCLC show moderate cytoplasmic but no nuclear reactivity (arrows); adjacent stromal and inflammatory cells are positive (arrowheads). C, D, Paraffin-embedded cell line U2OS shows positive nuclear staining for p14ARF (C) but not for p16INK4A (D). Original magnifications, 400 ×.

Immunohistochemical Evaluation of p14ARF Expression in Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Cell Lines and Tumors and Correlation with p16INK4a Expression

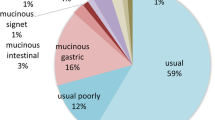

To demonstrate the general applicability of our p14ARF assay to archival specimens, we stained 34 cell buttons and 58 carcinomas. To study the relationship between p14ARF and p16INK4a expression in neoplastic cells, the same 92 specimens were stained for p16INK4a as well. As detailed in Tables 1 and 2 and, six cell lines were positive, and 18 were negative for both proteins. Of the six p14ARF+ cell lines, all but one (H719) had previously been shown to have a normal INK4a status. In addition, nude mouse xenografts of two lung cancer cell lines without detectable INK4a abnormalities reacted positively. Some cell lines showed prominent nucleolar reactivity on the p14ARF stains. Interestingly, 10 cell lines were negative for 16INK4a but expressed p14ARF (Fig. 1, C and D); the opposite staining pattern was not observed. We then studied 30 NSCLC and 28 pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Among the latter, all were p16INK4a negative, but nine expressed p14ARF (Table 3). Among the lung cancers, 16 cases expressed p16INK4a, and 18 were positive for p14ARF. However, the staining pattern for these two proteins did not coincide in eight of the 30 tumors (Table 3). Considering all test cell lines and tumors, the concordance rate for p16INK4a and p14ARF expression was 71% (19/92 positive and 46/92 negative for both). Although the expression patterns of these two proteins were significantly correlated (P < .0001, Fisher’s exact test), it is noteworthy that 24 cases were p16INK4a negative/p14ARF positive, while three cases were p16INK4a positive/p14ARF negative. In p14ARF and/or p16INK4a positive cell lines and tumors, a variable number of cells were devoid of nuclear reactivity.

Correlation between ARF Status and p14ARF Expression

For nine cell lines and 20 pancreatic carcinomas, information about ARF abnormalities at the DNA level was available. No nuclear staining was observed in cell lines with homozygous deletions of the INK4a locus (n = 4), promoter methylation of exon 1β (n = 2) or an intragenic mutation (n = 2) (Table 2). Colorectal cancer cell line SW837 has no known ARF abnormality and has an unmethylated exon 1β promoter (8), and this cell line expressed p14ARF. Similarly, all 12 pancreatic adenocarcinomas with INK4a deletions were p14ARF negative (Table 4). No data were available on the exon 1β methylation status in these cases. One silent and two frameshift mutations were associated with absence of nuclear staining. In contrast, three missense mutants produced positive nuclear immunoreactivity; two of these cases had identical mutations (Table 4). Two pancreatic carcinomas had INK4a mutations affecting only the p16INK4a open reading frame but not ARF, and both of these showed a positive immunohistochemical reaction pattern for p14ARF.

DISCUSSION

p16INK4a, one of the two proteins encoded by the INK4a gene, is one of the most frequent targets of inactivation in human cancers. The other INK4a-encoded protein, p14ARF, appears to have physiologic functions that only partially overlap with those of p16INK4a (1, 6, 15). p14ARF is an integral component of the p53/MDM2/p14ARF pathway and has bona fide tumor suppressor activity (16). However, it is not clear to what extent p14ARF is deregulated in human neoplasia.

We previously showed that IHC is an effective method to demonstrate abrogation of p16INK4a function in pathologic specimens (4, 5), and we set out to develop a similar assay for p14ARF. IHC allows evaluation of protein expression in specific cells and is applicable to most archival tissues. We are aware of only two previous immunohistochemical studies on p14ARF expression in human cancers (17, 18). Both of these used rabbit polyclonal antibodies, which are not commercially available, and only one of them was performed on paraffin sections (17).

Here we demonstrate that p14ARF expression can be evaluated in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues with commercially available reagents. Although we optimized the assay for only one of the five antibodies tested, monoclonal 14PO2 from NeoMarkers, which has been used before in immunofluorescence assays (19), it is quite possible that comparable results may be obtained with other anti-p14ARF antibodies. In agreement with earlier studies, the presence of immunoreactive p14ARF was indicated by granular or diffuse nuclear staining, with or without nucleolar accentuation (17, 18); cytoplasmic staining was observed even in cells with homozygous deletions of the INK4a gene and may thus be nonspecific. In some normal cells, cell lines and tumors, the staining pattern was predominantly nucleolar, consistent with the recently described nucleolar sequestration of MDM2 by p14ARF (7, 19, 20). The significance of the somewhat variable subcellular localization is unclear, but it does not seem to be related to fixation. The assay seems to have adequate sensitivity. A subset of non-neoplastic cells in various tissues, as well as five cell lines and two nude mouse xenografts with an intact INK4a gene, reacted positively. Not all cells with an intact ARF gene expressed p14ARF at a detectable level. It was previously shown that the intracellular level of p16INK4a is partly cell cycle dependant (21). It is conceivable that intracellular p14ARF levels are subject to similar variability, although we are not aware of detailed published studies on the regulation of p14ARF expression in normal or neoplastic cells.

The IHC reaction pattern in cell lines and tumors correlated well with the molecularly defined status of the INK4a gene that was available for some cell lines and for many of the pancreatic cancers, and with previous studies on p14ARF expression in some of the cell lines. All cell lines and tumors with homozygous INK4a deletions were devoid of nuclear reactivity above any cytoplasmic background. Colorectal carcinoma cell lines RKO and DLD-1 reportedly have methylated exon 1β promoters (8), and both of these failed to express the protein, whereas the unmethylated cancer cell line SW837 was p14ARF positive. Although some ARF mutations led to negative immunoreactivity, missense mutations produced positive nuclear staining (Tables 2 and 4). Thus, the presence of nuclear staining does not necessarily indicate the presence of normal p14ARF. Our data are consistent with earlier findings of p14ARF mRNA and protein expression in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells (20) and with absence of exon 1β promoter methylation in many colorectal cancer cell lines (8). T47D breast cancer cells were previously found to be p14ARF negative by immunofluorescence but positive by RT-PCR, and U20S osteosarcoma cells were reported to be negative but inducible for p14ARF (19). Both cell lines showed nuclear staining in our IHC assay, indicating good sensitivity.

However, the limits of the assay’s sensitivity have yet to be determined. It is possible that very low but physiologically significant levels of p14ARF may not be detectable by paraffin section IHC. Other potential problems with the immunohistochemical approach include variability in stain interpretation (our simple dichotomous scoring system should be rather robust) and a relatively poor signal-to-noise ratio due to seemingly low levels of antigen, especially in non-neoplastic tissues (15), and significant nonspecific background staining. However, as has been the case with p16INK4a, the latter problem is likely to be alleviated by the advent of second generation anti-p14ARF antibodies with improved sensitivity and specificity.

We found loss of p14ARF expression in 12 of 30 NSCLC, which is comparable with the rate of p14ARF down-regulation reported in three previous studies on this tumor type (17, 18, 22). All four studies agree that p14ARF loss is less common than down-regulation of p16INK4a. Five of our lung cancers were negative for p16INK4a but positive for p14ARF, and this phenotype was observed in two earlier studies (17, 18). Like Gazzeri et al. (18), but unlike Vonlanthen et al. (17), we also identified a smaller number of p16INK4a+/p14ARF− NSCLC. It was previously shown that almost all pancreatic carcinomas lack functional p16INK4a (13). Interestingly, nine of 30 pancreatic carcinomas were positive for p14ARF, suggesting that inactivation of this protein in this tumor type may not be as critical as abrogation of p16INK4a. Our data on cell lines and tumors support other studies that suggested that p16INK4a and p14ARF expression is differentially regulated, possibly due to methylation of only one of the two promoters in a given tumor or cell line (8). We believe our study to be the first to examine the relationship between these two markers at the protein level. In our series the concordance rate between p16INK4a and p14ARF immunoreactivity was 71% (24/34 cell lines, 22/30 NSCLC, 19/28 pancreatic cancers), which was statistically highly significant. However, 10 of 30 cell lines and 14 of 60 carcinomas had a p16INK4a−/p14ARF+ phenotype, while the opposite staining pattern was observed in three tumors. These findings support the notion that the two proteins encoded by the INK4a locus have nonredundant functions.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that it is possible to evaluate p14ARF expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues entirely with commercial reagents. The assay we describe should be applicable in any immunohistochemical laboratory. It may facilitate studies on the prevalence and pathobiologic and clinical significance of aberrant p14ARF expression in human neoplasia. We provide preliminary evidence that down-regulation of p14ARF is frequent in cancer cell lines and at least some tumors, but probably less common than p16INK4a inactivation. Finally, we have shown that expression of the two INK4a-encoded proteins may be discordant in a significant proportion of cell lines and cancers.

References

Stone S, Jiang P, Dayananth P, Tavtigian SV, Katcher H, Parry D, et al. Complex structure and regulation of the p16 (MTS1) locus. Cancer Res 1995; 55: 2988–2994.

Lukas J, Aagaard L, Strauss M, Bartek J . Oncogenic aberrations of p16INK4/CDKN2 and cyclin D1 cooperate to deregulate G1 control. Cancer Res 1995; 55: 4818–4823.

Liggett Jr WH, Sidransky D . Role of the p16 tumor suppressor gene in cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 1197–1206.

Geradts J, Kratzke RA, Niehans GA, Lincoln CE . Immunohistochemical detection of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2/multiple tumor suppressor gene 1 (CDKN2/MTS1) product p16INK4A in archival human solid tumors: correlation with retinoblastoma protein expression. Cancer Res 1995; 55: 6006–6011.

Geradts J, Hruban R, Schutte M, Kern S, Maynard R . Immunohistochemical p16INK4a analysis of archival tumors with deletion, hypermethylation, or mutation of the CDKN2/MTS1 gene: a comparison of four commercial antibodies. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2000; 81: 71–79.

Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG . ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell 1998; 92: 725–734.

Weber JD, Taylor LJ, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Bar-Sagi D . Nucleolar Arf sequesters Mdm2 and activates p53. Nat Cell Biol 1999; 1: 20–26.

Esteller M, Tortola S, Toyota M, Capella G, Peinado MA, Baylin SB, et al. Hypermethylation-associated inactivation of p14ARF is independent of p16INK4a methylation and p53 mutational status. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 129–133.

Otterson GA, Khleif SN, Chen W, Coxon AB, Kaye FJ . CDKN2 gene silencing in lung cancer by DNA hypermethylation and kinetics of p16INK4 protein induction by 5-aza 2′deoxycytidine. Oncogene 1995; 11: 1211–1216.

Geradts J, Maynard R, Birrer M, Hendricks D, Abbondanzo SL, Fong KM, et al. Frequent loss of KAI1 expression in squamous and lymphoid neoplasms: an immunohistochemical study of archival tissues. Am J Pathol 1999; 154: 1665–1671.

Lombardi DP, Geradts J, Foley JF, Chiao C, Lamb PW, Barrett JC . Loss of KAI1 expression in the progression of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 5724–5731.

Geradts J, Fong KM, Zimmerman PV, Maynard R, Minna JD . Correlation of abnormalities of RB, p16ink4a, and p53 expression with 3p loss of heterozygosity, other genetic abnormalities and clinical features in 103 primary non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 791–800.

Schutte M, Hruban RH, Geradts J, Maynard R, Hilgers W, Rabindran SK, et al. Abrogation of the RB/p16 tumor-suppressive pathway in virtually all pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 3126–3130.

Maitra A, Roberts H, Weinberg AG, Geradts J . Loss of p16(INK4a) expression correlates with decreased survival in pediatric osteosarcomas. Int J Cancer 2001; 95: 34–38.

Della Valle V, Duro D, Bernard O, Larsen C-J . The human protein p19ARF is not detected in hemopoietic human cell lines that abundantly express the alternative b transcript of the p16INK4a/MTS1 gene. Oncogene 1997; 15: 2475–2481.

Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Quelle DE, Downing JR, Ashmun RA, et al. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell 1997; 91: 649–659.

Vonlanthen S, Heighway J, Tschan MP, Borner MM, Altermatt HJ, Kappeler A, et al. Expression of p16INK4a/p16a and p19ARF/p16b is frequently altered in non-small cell lung cancer and correlates with p53 overexpression. Oncogene 1998; 17: 2779–2785.

Gazzeri S, Della Valle V, Chaussade L, Brambilla C, Larsen C-J, Brambilla E . The human p19ARF protein encoded by the b transcript of the p16INK4a gene is frequently lost in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 3926–3931.

Lindström MS, Klangby U, Inoue R, Pisa P, Wiman KG, Asker CE . Immunolocalization of human p14ARF to the granular component of the interphase nucleolus. Exp Cell Res 2000; 256: 400–410.

Stott FJ, Bates S, James MC, McConnell BB, Starborg M, Brookes S, et al. The alternative product from the human CDKN2A locus, p14ARF, participates in a regulatory feedback loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J 1998; 17: 5001–5014.

Tam SW, Shay JW, Pagano M . Differential expression and cell cycle regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4 inhibitor p16Ink4. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 5816–5820.

Sanchez-Cespedes M, Reed AL, Buta M, Wu L, Westra WH, Herman JG, et al. Inactivation of the INK4A/ARF locus frequently coexists with TP53 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 1999; 18: 5843–5849.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kwun Fong (The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia) for providing the lung cancer paraffin blocks, Dr. Scott Kern for providing the INK4a/ARF data, Dr. Andrew Graham for producing the composite figure, and Linda Summerville for typing the manuscript. This project was supported by a grant from the Oxfordshire Health Service Research Committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geradts, J., Wilentz, R. & Roberts, H. utImmunohistochemical Detection of the Alternate INK4a-Encoded Tumor Suppressor Protein p14ARF in Archival Human Cancers and Cell Lines Using Commercial Antibodies: Correlation with p16INK4a Expression. Mod Pathol 14, 1162–1168 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880452

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880452

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Roles of ARF tumour suppressor protein in lung cancer: time to hit the nail on the head!

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2021)

-

Alterations of ubiquitylation and sumoylation in conventional renal cell carcinomas after the Chernobyl accident: a comparison with Spanish cases

Virchows Archiv (2011)

-

The status of CDKN2A alpha (p16INK4A) and beta (p14ARF) transcripts in thyroid tumour progression

British Journal of Cancer (2006)

-

p16INK4A and p14ARF expression pattern by immunohistochemistry in human papillomavirus-related cervical neoplasia

Modern Pathology (2005)

-

p14ARF expression in invasive breast cancers and ductal carcinoma in situ– relationships to p53 and Hdm2

Breast Cancer Research (2004)