Abstract

The expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 in normal and neoplastic tissues and cell lines of the human lung was investigated using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization in conjunction with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. In normal lung tissues, immunoproducts of thyroid transcription factor-1 were observed in the nuclei of alveolar cells and bronchiolar cells. Interestingly, in distal bronchioles, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization revealed that thyroid transcription factor-1 was present not only in nonciliated cells (Clara cells) but also in ciliated cells and basal cells. In neoplastic tissues, thyroid transcription factor-1 was demonstrated in adenocarcinomas and small cell lung carcinomas with high frequency: 96% and 89% of cases, respectively. Thyroid transcription factor-1 was not detected in squamous cell carcinomas and large cell carcinomas. The strong immunoreactivity of thyroid transcription factor-1 or simultaneous expressions of thyroid transcription factor-1 and surfactant protein A tended to correlate with the differentiation phenotypes in adenocarcinomas; they were more frequently present in the well-differentiated type than were moderately and/or poorly differentiated types. By reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 messenger RNA was observed in squamous cell carcinomas in addition to in adenocarcinomas and small cell lung carcinomas, and this finding was confirmed in the cell lines from squamous cell carcinomas. Only one case of 99 adenocarcinomas that originated in various organs other than lung and thyroid immunohistochemically expressed thyroid transcription factor-1. Our results suggest that thyroid transcription factor-1 can play an important role for the maintenance and/or differentiation process in bronchiolar and alveolar cells. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression associates with histologic types and/or differentiation of lung cancers and can be a valuable marker for the better understanding of their biological nature and pathological behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is a homeodomain-containing nuclear transcription protein of Nkx2 gene family (1, 2). This kind of protein plays very important roles in the development, cell growth, and differentiation processes. TTF-1 was first identified in the follicular cells of the thyroid as a thyroid-specific DNA-binding protein, and it was subsequently demonstrated in the lung and in certain areas of the brain (3, 4, 5). In the thyroid, TTF-1 activates the transcription of thyroglobulin, thyroperoxidase, and thyrotropin receptor genes in follicular cells and of several genes associated with calcium metabolism in C cells (6, 7, 8). In the lung, the role of TTF-1 has been documented as a critical transcription factor that regulates the gene expression of lung-specific proteins such as Surfactant Proteins A (SP-A), B, and C and Clara cell secretory protein (9, 10, 11).

Recent immunohistochemical studies showed that TTF-1 is frequently expressed in lung carcinomas (2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). However, the previously reported frequencies vary considerably in different series: 27–76% of adenocarcinoma cases (2, 12, 15), 83–100% of small cell lung carcinoma cases (12, 13, 14), 0–25% of large cell carcinoma cases (12, 20), and 0–38% of squamous cell carcinoma cases (2, 14, 20). Therefore, it may be worthwhile to estimate the precise prevalence of TTF-1 expression in human lung carcinomas using different techniques together with immunohistochemistry.

Most previous immunohistochemical studies have focused on TTF-1 alone, and little is known about its correlation with surfactant proteins in human lung carcinomas (2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27). And there have been no reports on the in situ expression of TTF-1 mRNA. Therefore we investigated the expression and localization of TTF-1 and SP-A in normal and neoplastic lung tissues by immunohistochemistry and nonisotopic in situ hybridization in conjunction with reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to determine whether TTF-1 expression profiles are of value for pathological diagnosis and for prediction of the biological behavior of lung carcinomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Preparation

A series of surgical specimens from patients with lung tumors comprised of adenocarcinoma (52 cases), squamous cell carcinoma (26 cases), small cell lung carcinoma (18 cases), large cell carcinoma (8 cases), and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (3 cases) were selected from the surgical files of Yamanashi Medical University Hospital to represent a wide range of lung cancer. The histological typings of lung carcinomas were classified according to the third edition of Histological Typing of Lung Tumors (World Health Organization [WHO], 28). We determined histological gradings (well, moderately, and poorly differentiated) of the adenocarcinoma according to WHO classification (28), carried out by applying conventional histological criteria to architectural patterns and cytological features. Tumors with extensive solid components were classified as poorly differentiated carcinoma.

In addition, we examined 99 adenocarcinomas that originated from other organs, including colon (25 cases), stomach (23 cases), pancreas (15 cases), prostate (15 cases), gallbladder (10 cases), and breast (11 cases). All specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde, processed routinely, and embedded in paraffin wax.

Cell Lines

The 14 cell lines consisted of 4 lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (A549, 1–87, 11–18, and LK87S), 4 lung squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (Sq-1, Sq-19, EBC-1, and LK-2), 4 small cell lung carcinoma cell lines (LK79, S2, LU65, and 87–5), and 2 lung large cell carcinoma cell lines (Lu99 and Lu99B). All these samples were provided from Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research of Tohoku University. These cell lines were incubated under the optimal conditions for each cell line.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical analysis, the following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal antibody against TTF-1 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) and mouse monoclonal antibody against SP-A (DAKO JAPAN, Kyoto, Japan; 29) at a dilution of 1:50.

For TTF-1 immunostaining, heat pretreatment of the paraffin sections was employed for antigen retrieval as described in the appending sheet. Sections with 3- or 4-μm thickness were cut and mounted on poly-l-lysine–coated slides. Deparaffinized sections were placed first in plastic Coplin jars filled with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and incubated for 10 min at 120° C in an autoclave. After autoclave pretreatment, the sections were allowed to cool to room temperature and then were exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide in water to inactivate endogenous peroxidase.

Indirect immunoperoxidase staining was used according to standard protocols (30). The sections were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the primary antibodies. Antimouse immunoglobulin G conjugate serum was applied to the sections for 60 minutes at room temperature, and the peroxidase reaction was performed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (3,3′-diaminobenzidine). The immunohistochemical preparations were counterstained with methyl green or hematoxylin.

For serum controls, normal mouse serum or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was used instead of the primary antibody. Thyroid tissues were used as a positive control.

Positive cases were represented as + or ++ (+, positive cells <20% of tumor cells; ++, positive cells >20% of tumor cells). Two of the authors (NN and RK) estimated the immunoreactive cells separately and determined the positive cases.

In Situ Hybridization

A plasmid encoding a mouse subclone of the TTF-1 genome was supplied by Roberto di Lauro, Ph.D. (Stazione Zoologica A. Dohrn, Villa Comunale, Naples, Italy). For riboprobe preparation, a 757-bp SacII fragment (149–905 bp) of TTF-1 cDNA was subcloned into Bluescript SK+ (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA). The plasmid was linearized with restriction enzyme NotI and was washed by phenol–chloroform extraction. The purified, linearized plasmid was used to generate labeled RNA antisense probes by performing in vitro transcription using T3 RNA polymerase and digoxigenin-11-uridine-5′-triphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH Biochemica, Mannheim, Germany). In the same way, the sense probe was made using the restriction enzyme BglII and T7 RNA polymerase.

The in situ hybridization protocol was a modification of a method described by Katoh et al. (7). In brief, sections were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated with a graded series of ethanol solutions, rinsed in PBS at pH 7.4, postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, rinsed in PBS, and digested with 20 μg/mL proteinase K (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 37° C for 20 minutes. Slides were fixed again with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, rinsed with PBS, dehydrated in graded solutions of ethanol, and air dried.

Probes were diluted with hybridization solution (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, containing 50% formamide, 200 μg/mL transfer RNA, 1× Denhardt’s solution, 10% dextran sulfate, 600 mmol/L NaCl, 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA]) to a final concentration of 1 ng/mL, and sections were hybridized with a heat-denatured riboprobe for 18 hours at 55° C. The hybridization samples were washed sequentially in 5× SSC (sodium chloride and sodium citrate) for 5 minutes at 55° C, then in 2× SSC containing 50% formamide for 30 minutes at 55° C; 1× SSC is composed of 0.15 mol/+ NaCl and 0.015 mol/L sodium citrate. To degrade unbound riboprobe, sections were treated with RNase A (1 μg/mL in 10 mmol/L EDTA) at 37° C for 30 minutes, then sequentially washed once in 2× SSC for 20 minutes at 55° C and twice in 0.2× SSC for 20 minutes at 55° C.

The hybridized probe was detected using a Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH Biochemica) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, slides were incubated with 1.5% blocking reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature, then with a 1:500 dilution of alkaline phosphatase–labeled sheep antidigoxigenin Fab fragment for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, slides were incubated with substrate solution containing nitroblue tetrazolium salt and X-phosphate (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl phosphate) for 2 to 12 hours, counterstained with methyl green, and mounted using a glycerin–gelatin solution.

Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA were prepared by the acid guanidinium-phenol-chloroform system (ISOGEN, Nippon Gene Co Ltd, Toyama, Japan) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated total RNA (20 μg) was fractionated by electrophoresis of 1.5% agarose in 18% formaldehyde gels. The quality of the extracted RNAs showing two clear bands of 28S and 18S, corresponding to ribosomal RNAs, were selected for further studies. Five micrograms of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. PCRs were carried out according to the Gene Amp DNA amplification reagent kit instructions (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). Thirty cycles were performed. During each cycle, the samples were heated to 94° C for 30 seconds, cooled to 56° C for 60 seconds, and heated to 72° C for 60 seconds. The RT-PCR reagent blank yielded no detectable products. A 16-μL sample of each 50-μL PCR solution was fractionated by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel. Gels were photographed using Polaroid 655 film. The oligonucleotide primer sequences for TTF-1, SP-A, and β-actin are described in Table 1. RNAs extracted from the stomach, colon, and liver were used as the negative tissue control.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemistry and In Situ Hybridization

Normal Tissues

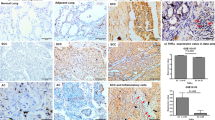

In the current immunohistochemical study, the immunoreactive products of TTF-1 protein were clearly identified in the nuclei of alveolar cells, possibly indicating Type II cells (Fig. 1, A–B). This finding was supported by in situ hybridization; alveolar cells with round nuclei were strongly hybridized with a specific riboprobe for TTF-1 mRNA (Fig. 1C). TTF-1 protein was also observed in the nuclei of ciliated and nonciliated cells in terminal and respiratory bronchioles (Fig. 1F). There was a tendency for stronger TTF-1 immunostaining in nonciliated Clara cells than in ciliated bronchiolar cells. Furthermore, in parts of the distal bronchiole, TTF-1 was observed in the nuclei of basal cells but not in goblet cells (Fig. 1J). The mRNA of TTF-1, however, was evident with in situ hybridization in some goblet cells as well as in basal cells in distal bronchiole (Fig. 1K). The immunoreactive products of SP-A were observed in the cytoplasm of nonciliated Clara cells and alveolar Type II cells (Fig. 1, D & H).

Normal lung. A–D, alveolar Type II cell (arrow) showing positive staining of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) protein (B), TTF-1 mRNA (C), and Surfactant Protein A (SP-A; D). E–H, ciliated cells (arrowheads) and nonciliated Clara cells (arrow) showing positive staining of TTF-1 protein (F) and mRNA (G). Note the positive staining of SP-A only in nonciliated Clara cells (H). I–K, basal cells (arrows) in distal bronchiole showing a positive nuclear staining of TTF-1 protein (K). Note the cytoplasmic expression of TTF-1 mRNA in the basal and bronchiole cells (J). Hematoxylin and eosin staining (A, E, I), immunohistochemistry of TTF-1 (B, F, J) and SP-A (D, H), in situ hybridization of TTF-1 mRNA (C, G, K). Original magnification, 600×.

Neoplastic Tissues

Positive Frequency of TTF-1 and SP-A in Lung Carcinomas. The immunohistochemical results of TTF-1 and SP-A in lung cancers are summarized in Table 2. The immunopositivities of TTF-1 were located in the nuclei of neoplastic cells in adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2) and small cell lung carcinoma (Fig. 3) and were not found in squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma. The positive frequencies in adenocarcinomas and small cell lung carcinomas were 96% and 89% of cases, respectively (Table 2). Thirty-eight of 52 adenocarcinoma cases (73%) and all but two small cell lung carcinoma cases showed strong immunoreactions of TTF-1 (Table 2). In situ hybridization using a specific riboprobe for the TTF-1 gene revealed a high expression of TTF-1 mRNA in the cytoplasm of tumor cells that showed a strong immunoreactivity for TTF-1 (Figs. 2C and 3C).

Human lung adenocarcinoma. A, hematoxylin and eosin stain. B, immunohistochemistry of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) showing a positive staining of TTF-1 protein in the nuclei of adenocarcinoma cells. C, in situ hybridization showing the TTF-1 m RNA signals in the cytoplasms of cancer cells. D, immunohistochemistry of Surfactant Protein A showing it positively stained in the cytoplasms of the cancer cells. Original magnification, 100×.

Human small cell lung carcinoma. A, hematoxylin and eosin stain. B, immunohistochemistry of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) showing the positive staining of TTF-1 protein in the nuclei of the small cell lung carcinoma cells. C, in situ hybridization showing the TTF-1 m RNA signals in the cytoplasms of the cancer cells. D, immunohistochemistry of Surfactant Protein A showing no staining of it in the cytoplasms of the cancer cells. Original magnification, 400×.

In contrast to TTF-1 immunostaining, distinctive cytoplasmic immunoreactions of SP-A in neoplastic cells were only demonstrated in 73% of adenocarcinoma cases (Figs. 2D and 3D) and not in other types of lung carcinomas (Table 2).

Tumor Differentiation and Expression of TTF-1 and SP-A in 52 Adenocarcinomas. Tables 3 and 4 summarize the immunohistochemical relations between TTF-1 and SP-A in 52 adenocarcinomas. A strong TTF-1 immunoreactivity (representing ++) was found in 100% of cases in well-differentiated cancers, 76% of cases in moderately differentiated cancers, and 50% of cases in poorly differentiated cancers (Table 3). In contrast to this, strong SP-A immunoreactions (representing ++) were less frequently observed in all types in adenocarcinoma: 37% of cases in the well-differentiated type, 31% of cases in the moderately differentiated type, and 25% of cases in the poorly differentiated type. Simultaneous positivity of TTF-1 and SP-A (representing +/+) was most frequently observed in the well-differentiated type of adenocarcinomas (89%) and less frequently in the moderately (62%) and poorly (50%) differentiated adenocarcinomas (Table 4). The tumors showing TTF-1 positivity and SP-A negativity (representing +/−) were most frequently observed in poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas (50%). There were no tumors showing TTF-1 negativity and SP-A positivity in the present series.

Adenocarcinoma with Other Origins. We examined the TTF-1 expressions in 99 adenocarcinomas with other origins including the colon, stomach, pancreas, prostate, gall bladder, and breast (Table 5). Among these cancers, TTF-1 was demonstrated only in one case of stomach cancer, which showed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. In this tumor, TTF-1 was identified in the nuclei of spindle cells and not in the cells forming tubules (data not shown). In addition, three cases of metastatic lung cancer that originated from the liver were also negative for TTF-1 protein and mRNA and for SP-A protein.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

In tissue materials, RT-PCR revealed that mRNA expressions of TTF-1 and SP-A were demonstrated in squamous cell carcinoma as well as in adenocarcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma (Fig. 4A). SP-A mRNA expression was present in adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma and was absent in small cell lung carcinoma. In large cell carcinoma tissues, no specific band of TTF-1 mRNA was obtained (Fig. 4A).

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction of analysis of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), Surfactant Protein A (SP-A), and β-actin in human lung tissues (A) and cell lines (B). A, TTF-1 mRNA expression is present in Lanes 1 (adenocarcinoma), 2 (squamous cell carcinoma), 3 (small cell lung carcinoma), and P (normal lung tissue). Note the absence of TTF-1 mRNA expression in Lane 4 (large cell carcinoma). Thy, normal thyroid tissue; P, positive control (normal lung tissue); N, negative control; M, marker. B, TTF-1 mRNA expression is present in Lanes 2 (1–89), 3 (11–18), 5 (Sq-1), 6 (Sq-19), 8 (LK-2), 9 (LK-79), 10 (S2), and 12 (87–5) and is absent in Lanes 1 (A549), 4 (LK87), 7 (EBC-1), 11 (Lu65), 13 (Lu99), and 14 (Lu99B). P, positive control (normal lung tissue); M, marker.

RT-PCR analyses for TTF-1 and SP-A mRNAs were also performed in 14 lung carcinomas cell lines including 4 adenocarcinomas, 4 squamous cell carcinomas, 4 small cell lung carcinomas, and 2 large cell carcinomas (Fig. 4B). TTF-1 mRNA was expressed in 2 of 4 adenocarcinoma cell lines, 3 of 4 squamous cell carcinoma cell lines, and 3 of 4 small cell lung carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 4; Table 6). TTF-1 protein was demonstrated immunohistochemically in all but one cell line expressing TTF-1 mRNA (Table 6). No distinctive band of TTF-1 mRNA was obtained in two large cell carcinoma cell lines. The expression of SP-A mRNA was demonstrated only in one of four adenocarcinoma cell lines and in one of four squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 5; Table 6).

Immunohistochemistry of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and Surfactant Protein A (SP-A) in two cell lines, 1–87 (A–C) and Sq-19 (D–F). Lines 1–87 from human adenocarcinoma showing positive staining of TTF-1 protein (B) and SP-A protein (C). Sq-19 from human squamous cell carcinoma showing positive staining of TTF-1 protein (E) and negative of SP-A protein (F). Original magnification, 200×.

DISCUSSION

The present study was undertaken to clarify the expression and localization of TTF-1 in normal and neoplastic lung tissues using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization in conjunction with RT-PCR. In the lung, it has been suggested that TTF-1 regulates the transcription of genes encoding lung-specific proteins such as Surfactant Apoproteins A, B, and C and Clara cell secretory protein (9, 10, 11). In the current immunohistochemical study, the immunoreactive products of TTF-1 were identified in the nuclei of alveolar cells and bronchiolar cells and were not demonstrated in bronchial cells. Surfactant proteins are produced in alveolar cells, and Clara cells secrete Clara cell secretory protein. Therefore, the present results supported the finding that TTF-1 regulates the secretory function of these pulmonary cells. Interestingly, in bronchioles, TTF-1 was found not only in nonciliated Clara cells but also in ciliated cells and basal cells. This finding has not been described in previous studies. In general, it is suggested that ciliated bronchiolar cells are closely related to nonciliated Clara cells. Therefore, TTF-1 expression in ciliated bronchiolar cells is not a surprising finding, and TTF-1 may play some roles in ciliated bronchiolar cells. The present results also showed the expression of TTF-1 in basal bronchiole cells that appeared in distal bronchioles, and they did not immunoreact with antibody for SP-A. Therefore, TTF-1 does not always introduce SP-A. The basal cells form a stem cell population from which the other cell type developed (31). In this respect, it is suggested that TTF-1 may contribute to the maintenance of the bronchiolar cell differentiation process.

To better clarify the precise expression and localization of TTF-1 mRNA, we performed the in situ hybridization technique together with immunohistochemistry. To the best of our knowledge, in situ expression of TTF-1 mRNA has not been described in lung tissues. On in situ hybridization observation, the expression of TTF-1 mRNA was basically demonstrated in the cytoplasms of the pulmonary cells that were positive by the immunohistochemical study. However, the cells hybridized with the specific riboprobe appeared to be more extensive compared with positive cells by immunohistochemistry. It could be reasonable to suggest that in situ hybridization analysis together with immunohistochemistry can be useful for accurate assessment of TTF-1 expression in the lung tissues.

In the present study, TTF-1 was immunohistochemically demonstrated in 96% of adenocarcinoma cases. This result is rather high compared with the frequencies reported in other studies: frequency of TTF-1 ranged from 27–76% of adenocarcinoma cases (2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20). Recently, Lau et al. (15) reported that all mucinous carcinomas originated from the lung were observed to be TTF-1 negative and that 75% of nonmucinous carcinomas and 86% of mixed carcinomas (mixed nonmucinous and mucinous carcinoma) were positive for TTF-1. All adenocarcinomas studied here were not regarded as mucinous carcinoma, but several tumors included small areas showing mucin production. These mucinous parts were negative for TTF-1. Therefore, the high prevalence rate (96%) of TTF-1 in adenocarcinomas in the present study may be due to lack of mucinous carcinoma cases.

There have been no studies reported on TTF-1 expression in adenocarcinomas originating in organs other than the lung and thyroid. In this respect, we additionally examined 99 adenocarcinomas that occurred in several other organs including the colon, stomach, pancreas, prostate, gall bladder, and breast and demonstrated TTF-1 positivity only in one case of stomach adenocarcinoma with a poorly differentiated phenotype. From these results, the potential diagnostic value of TTF-1 in pulmonary carcinomas appears to be promising.

TTF-1 was implicated in regulation of differentiation genes in lung, such as Surfactant Proteins A, B, and C, and 10-kDa Clara cell gene promoters (1, 5, 9, 10, 11). Therefore, TTF-1 expression could be associated with the functional differentiation in lung carcinomas. The findings of the current immunohistochemical study revealed that TTF-1 was identified in all but two cases of adenocarcinoma, and a strong immunoreactivity of TTF-1 was more frequently observed in the well-differentiated phenotype than in the less differentiated phenotypes. Therefore, TTF-1 expression could be related to the functional differentiation of adenocarcinoma. Linnoila et al. (32) suggested that expression of Surfactant Apoprotein A and the 10-kDa Clara cell gene promoters were independent prognostic indicators for survival and delayed development of metastases in patients with early-stage non–small cell lung cancer. Taken together, it is suggested that a strong expression of TTF-1 can predict a better prognosis of adenocarcinoma. However, Puglisi et al. (19) reported that TTF-1 protein is an adverse prognostic factor and that a strong expression of TTF-1 is associated with a higher risk of death.

Small cell lung carcinomas frequently express TTF-1; the frequency of TTF-1 expression reported in several different series has ranged from 83–100% (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 22). Interestingly, more recent studies showed that TTF-1 is also expressed in extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (24, 33). In the present study, the high prevalence of TTF-1 was demonstrated in 90% of small cell lung carcinoma cases. In addition, our in situ hybridization and RT-PCR analysis confirmed a strong expression of TTF-1 mRNA in small cell lung carcinoma. Therefore, TTF-1 is suggested as a sensitive marker for small cell lung carcinoma. Although the precise significance of TTF-1 expression in small cell carcinoma is still unclear, the common expression of TTF-1 in adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma, as shown in the current study, may support the view that small cell lung carcinoma develop from an endodermal precursor and, therefore, small cell lung carcinoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma appear to develop from a common epithelial stem cell (34).

In previous immunohistochemical studies, TTF-1 was demonstrated in some cases of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma (2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20). In addition, it is known that some squamous cell carcinomas show focal mucin on histochemical stains (28). We failed to demonstrate the immunohistochemical expression of TTF-1 in all 26 pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma tissues. However, in contrast, the present RT-PCR analysis revealed mRNA expressions of TTF-1 and SP-A in similar materials. This finding may be the result of entrapment of normal lung cells expressing TTF-1 mRNA such as Type II alveolar cells and bronchiolar cells. Indeed, squamous cell carcinoma tissues sometimes contain a small amount of normal lung cells in their peripheral areas. In this respect, it suggested that in situ hybridization studies can be useful to rule out this possibility. The present in situ hybridization study with a specific riboprobe for TTF-1 revealed that the convincing expression of TTF-1 mRNA was not demonstrated in squamous cell carcinoma cells. This result suggests that TTF-1 mRNA expression detected by RT-PCR may be due to entrapped normal lung cells and, therefore, the expression of TTF-1 mRNA may be absent or very small in squamous cell carcinoma cells. Surprisingly, however, RT-PCR analysis for RNAs extracted from the four cell lines of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma revealed that the expression of TTF-1 mRNA was demonstrated in three cell lines, and the expression of SP-A mRNA, in one cell line. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that some squamous cell carcinomas could have originated from the cells expressing TTF-1 and/or SP-A.

In conclusion, TTF-1 is not only expressed from nonciliated Clara cells and alveolar cells but also from ciliated and basal cells in the distal bronchiole in connection with their functional ability and/or differentiation process. In neoplastic lung tissues, TTF-1 is one of most reliable markers for pulmonary adenocarcinoma and small cell lung carcinoma. Therefore, additional investigations of TTF-1 may provide useful information on the assessment of the functional nature and clinical behavior of these lung malignancies.

References

Ikeda K, Clark JC, Shaw-White JR, Stahlman MT, Boutell CJ, Whitsett JA . Gene structure and expression of human thyroid transcription factor-1 in respiratory epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 8108–8114.

Bejarano PA, Baughman RP, Biddinger PW, Miller MA, Fenoglio-Preiser C, al-Kafaji B, et al. Surfactant proteins and thyroid transcription factor-1 in pulmonary and breast carcinomas. Mod Pathol 1996; 9: 445–452.

Civitareale D, Lonigro R, Sinclair AJ, Di Lauro R . A thyroid-specific nuclear protein essential for tissue-specific expression of the thyroglobulin promoter. EMBO J 1989; 8: 2537–2542.

Stahlman MT, Gray ME, Whitsett JA . Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1(TTF-1) in fetal and neonatal human lung. J Histochem Cytochem 1996; 44: 673–678.

Lazzaro D, Price M, de Felice M, Di Lauro R . The transcription factor TTF-1 is expressed at the onset of thyroid and lung morphogenesis and in restricted regions of the foetal brain. Development 1991; 113: 1093–1104.

Katoh R, Kawaoi A, Miyagi E, Li X, Suzuki K, Nakamura Y, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 in normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic follicular thyroid cells examined by immunohistochemistry and nonradioactive in situ hybridization. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 570–576.

Katoh R, Miyagi E, Nakamura N, Li X, Suzuki K, Kakudo K, et al. Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in human C cells and medullary thyroid carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 386–393.

Oguchi H, Kimura S . Transcription factors and thyroid disease. Mol Med 1995; 32: 518.

Zhang L, Whitsett JA, Stripp BR . Regulation of Clara cell secretory protein gene transcription by thyroid transcription factor-1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997; 1350: 359–367.

Bohinski RJ, Di Lauro R, Whitsett JA . The lung-specific surfactant protein B gene promoter is a target for thyroid transcription factor 1 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3, indicating common factors for organ-specific gene expression along the foregut axis. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14: 5671–5681.

Bruno MD, Bohinski RJ, Huelsman KM, Whitsett JA, Korfhagen TR . Lung cell-specific expression of the murine surfactant protein A (SP-A) gene is mediated by interactions between the SP-A promoter and thyroid transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 6531–6536.

Fabbro D, Di Loreto C, Stamerra O, Beltrami CA, Lonigro R, Damante G . TTF-1 gene expression in human lung tumours. Eur J Cancer 1996; 32A: 512–517.

Holzinger A, Dingle S, Bejarano PA, Miller MA, Weaver TE, DiLauro R, et al. Monoclonal antibody to thyroid transcription factor-1: production, characterization, and usefulness in tumor diagnosis. Hybridoma 1996; 15: 49–53.

Harlamert HA, Mira J, Bejarano PA, Baughman RP, Miller MA, Whitsett JA, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 and cytokeratins 7 and 20 in pulmonary and breast carcinoma. Acta Cytol 1998; 42: 1382–1388.

Lau SK, Desrochers MJ, Luthringer DJ . Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20 in bronchioloalveolar carcinomas: an immunohistochemical evaluation of 67 cases. Mod Pathol 2002; 15: 538–542.

Di Loreto C, Di Lauro V, Puglisi F, Damante G, Fabbro D, Beltrami CA . Immunocytochemical expression of tissue specific transcription factor-1 in lung carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 1997; 50: 30–32.

Di Loreto C, Puglisi F, Di Lauro V, Damante G, Beltrami CA . TTF-1 protein expression in pleural malignant mesotheliomas and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Lett 1998; 124: 73–78.

Bohinski RJ, Bejarano PA, Balko G, Warnick RE, Whitsett JA . Determination of lung as the primary site of cerebral metastatic adenocarcinomas using monoclonal antibody to thyroid transcription factor-1. J Neurooncol 1998; 40: 227–231.

Puglisi F, Barbone F, Damante G, Bruckbauer M, Di Lauro V, Beltrami CA, et al. Prognostic value of thyroid transcription factor-1 in primary, resected, non-small cell lung carcinoma. Mod Pathol 1999; 12: 318–324.

Kaufmann O, Dietel M . Thyroid transcription factor-1 is the superior immunohistochemical marker for pulmonary adenocarcinomas and large cell carcinomas compared to surfactant proteins A and B. Histopathology 2000; 36: 8–16.

Ordonez NG . Value of thyroid transcription factor-1 immunostaining in distinguishing small cell lung carcinomas from other small cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 1217–1223.

Byrd-Gloster AL, Khoor A, Glass LF, Messina JL, Whitsett JA, Livingston SK, et al. Differential expression of thyroid transcription factor 1 in small cell lung carcinoma and Merkel cell tumor. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 58–62.

Miettinen M, Franssila KO . Variable expression of keratins and nearly uniform lack of thyroid transcription factor 1 in thyroid anaplastic carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 1139–1145.

Agoff SN, Lamps LW, Philip AT, Amin MB, Schmidt RA, True LD, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 is expressed in extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas but not in other extrapulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 238–242.

Shimosato Y . Pulmonary neoplasms.In: Stephen SS, editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology. 3th ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. p. 1069–1115.

Mizutani Y, Nakajima T, Morinaga S, Gotoh M, Shimosato Y, Akino T, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of pulmonary surfactant apoproteins in various lung tumors. Cancer 1988; 61: 532–537.

Nicholson AG, McCormick CJ, Shimosato Y, Butcher DN, Sheppard MN . The value of PE-10, a monoclonal antibody against pulmonary surfactant, in distinguishing primary and metastatic lung tumours. Histopathology 1995; 27: 57–60.

Travis WD, Colby TV, Corrin B, Shimosato Y, Brambilla E . Histological typing of lung and pleural tumors.In: World Health Organization international classification of tumors. 3rd ed. Berlin, NY: Springer; 1999.

Hiraike N, Sohma H, Kuroki Y, Akino T . Epitope mapping for monoclonal antibody against human surfactant protein A (SP-A) that alters receptor binding of SP-A and the SP-A-dependent regulation of phospholipid secretion by alveolar type II cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995; 1257: 214–222.

Nakane PK, Kawaoi A . Peroxidase-labeled antibody. A new method of conjugation. J Histochem Cytochem 1974; 22: 1084–1091.

Alan S, James L . In: Respiratory system. Human histology. 2nd ed. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby; 1997.

Linnoila RI, Jensen SM, Steinberg SM . Peripheral airway cell marker expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1992; 97: 233–243.

Kaufmann O, Dietel M . Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 in pulmonary and extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas and other neuroendocrine carcinomas of various primary sites. Histopathology 2000; 36: 415–420.

Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD, Baylin SB . Origin of human small cell lung cancer. Science 1985; 229: 679–680.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude is expressed to Syunsuke Kobayashi of the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research’s, Tohoku University, Japan for generously donating the cell lines. We are also grateful to Mrs. Yoda, Mrs. Ito, and Mrs. Gomi for help in immunohistochemical preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, N., Miyagi, E., Murata, Si. et al. Expression of Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 in Normal and Neoplastic Lung Tissues. Mod Pathol 15, 1058–1067 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000028572.44247.CF

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000028572.44247.CF

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Outcomes of surgical resection for pulmonary metastasis from pancreatic cancer

Surgery Today (2023)

-

Significance of pulmonary resection in patients with metachronous pulmonary metastasis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study

BMC Surgery (2021)

-

Long-term survival after repeated resection for lung metastasis originating from pancreatic cancer: a case report

Surgical Case Reports (2020)

-

Reaching the limits of prognostication in non-small cell lung cancer: an optimized biomarker panel fails to outperform clinical parameters

Modern Pathology (2017)

-

Neural lineage-specific homeoprotein BRN2 is directly involved in TTF1 expression in small-cell lung cancer

Laboratory Investigation (2013)