Abstract

Steatohepatitis, of either alcoholic or nonalcoholic etiologies, is ultimately diagnosed by clinical-pathologic correlation and is characterized histologically by lesions that differ from the portal-based chronic inflammation and fibrosis of most other forms of chronic liver disease. With the increasing prevalence of steatohepatitis in our society, it is likely that some patients will have coexistent clinical and/or histopathologic findings of steatohepatitis concurrently with another form of liver disease. The aim of this study was to document clinical and histologic findings in biopsies in an academic referral center. Ninety-three non-allograft liver biopsies with lesions of both steatohepatitis and another liver disease were retrospectively identified in 85 patients. The finding of coexisting disease represented 5.5% of all hepatitis C biopsies and 4.0% of other forms of chronic liver disease in the 34 month time period. Clinical chart review of patients with concurrent disease showed the following: Group 1, patients with hepatitis C (n = 54); Group 2, patients with hepatitis C and prior or current history of more than 80 g/d alcohol consumption (n = 20); Group 3, patients with other forms of chronic liver disease (n = 11). Groups 1 and 3 had <10 g/d alcohol use. Obesity (body mass index >30) was noted in 75%, 60%, and 33% respectively, while 94%, 87% and 100% of patients were considered overweight (body mass index ≥ 25). Diabetes was reported in 35%, 25%, and 9%. The concurrence of clinical and histologic features of steatohepatitis with another chronic liver disease may be a reflection of the frequency of steatohepatitis in the population at large.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the current nomenclature for a chronic, progressive form of liver disease of diverse and incompletely understood etiologies; nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is being recognized with increasing frequency in adult and pediatric populations in the western world (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). The histologic features that characterize nonalcoholic steatohepatitis were documented in the well-known study by Ludwig et al. in 1980(4). The constellation of histologic lesions, which are similar regardless of the etiopathogenesis (2, 4, 5, 6), are considered to be morphologic manifestations of complex metabolic derangements and consequent necroinflammatory lesions that result in hepatocellular fat accumulation, liver cell injury, parenchymal inflammation and perisinusoidal fibrosis that may progress to cirrhosis. The histologic features of steatohepatitis are commonly noted to be predominantly found in zone 3 of the acinus of precirrhotic biopsies, and are distinct from the characteristic portal-based chronic inflammation and fibrosis, and spotty lobular necrosis of most other forms of chronic viral, metabolic and cholestatic liver disease (7).

More than one disease process may concurrently involve the liver; the lesions may be distinguishable by histopathologic examination. In some settings, coexistence of more than one process may be significant in disease progression. Some examples include hepatitis C and B (8, 9, 10), hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease (11, 12), hemochromatosis, and/orHFE mutations in patients with several other forms of viral and metabolic liver disease (13, 14, 15, 16). Although some of the histologic lesions found in various entities of differing etiologies may be similar, or may be considered “nonspecific” necroinflammatory findings, careful microscopic examination may allow for discrimination of lesions for an accurate diagnosis (7). It has been our experience that the constellation of histologic features of steatohepatitis may also be recognized in biopsies from patients with another serologically and/or clinically determined form of chronic liver disease. The purpose of this study was to document the frequency of such cases in a large biopsy service in an academic referral center, and retrospectively review the clinical features of the selected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

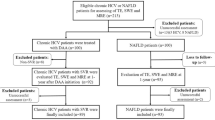

A computer search of the Pathology files of Saint Louis University Health Sciences Center from June 1997 to April 2000 for the specific diagnosis of “steatohepatitis” was performed. This file included in-house and consultation needle liver biopsies of adult patients evaluated by hepatologists in the Liver Clinic of Saint Louis University Health Sciences Center. After allograft liver biopsies were excluded, biopsies with both the histopathologic diagnosis of steatohepatitis, and another serologically or historically-defined liver disease were collected. The selected biopsies were reviewed; for purposes of this study only cases with at least zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis were included as a means to exclude cases with steatosis and lobular inflammation only, and specifically those in which overlapping features of steatosis and lobular chronic inflammation are likely attributable to hepatitis C. These are more stringent criteria for steatohepatitis than are applied to “uncomplicated” steatohepatitis, in which there may be cases without zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis (17). In addition, the following features were documented: amount of steatosis (1 = up to 33%; 2 = 33–66%; 3 = more than 66%), location of steatosis (i.e., zone 3 predominant or diffuse), presence or absence of Mallory’s hyaline as detected by H&E stains; acinar location and extent of involvement by perisinusoidal fibrosis; and, when applicable, portal fibrosis stage by Scheuer’s system (18). Twenty-five biopsies with cirrhosis were selected after review because of extensive perisinusoidal fibrosis and steatosis with or without Mallory’s hyaline.

From the identified patients, clinical charts were reviewed for the information as close as possible to the date of the liver biopsy: gender, age, weight and height, blood pressure, clinically-determined etiology of liver disease; serum levels of aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase–alanine transaminase ratio, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin; presence of hypercholesterolemia as defined by cholesterol more than 200 mg/dL and hypertriglyceridemia, as defined by serum triglycerides >250 mg/dL; use of medications for diabetes, hypertension, and lipid lowering, and current or past use of alcohol. Hepatitis C genotypes were recorded where available. The body mass index was calculated from stated height and weight measurements and obesity was defined as body mass index more than 30. Eight patients had had two different biopsies identified by the search, and clinical values from the time of the first biopsy were those used in this study.

Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaStat, SSPS, Chicago, IL.

This retrospective slide and chart review study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Louis University.

RESULTS

The computer search yielded a total of 3581 biopsies during the specified 34-month period. Of these, steatohepatitis was one of the diagnoses, or the only pathologic diagnosis on record in 419 (11.7% of total) cases. After re-review, 93 (2.6% of total biopsies) biopsies from 85 patients fulfilled the clinical (non-allograft) and histopathologic criteria (requirement for pericellular fibrosis) as stated above for this review.

Table 1 shows the incidence of concurrent steatohepatitis with another liver disease diagnosed by biopsy in our academic liver biopsy series. Coexistence of steatohepatitis was seen in biopsies from 74 patients with hepatitis C, which reflected 5% of all biopsies from patients with hepatitis C during the specified time. The other liver diseases with concurrent steatohepatitis were primary biliary cirrhosis (4 patients), autoimmune hepatitis (1 patient), alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (2 patients), hepatitis B (2 patients), iron overload C282Y/wt (1 patient), and drug-induced (nitrofurantoin) hepatitis (1 patient). Coexistent steatohepatitis in non-hepatitis C patients ranged from 1.6% (autoimmune hepatitis) to 7.9% (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency); in aggregate, 4.0% of all other forms of chronic liver disease. The statistical incidence of co-existent steatohepatitis with chronic hepatitis C was not greater than in the other forms of chronic liver disease (P = n.s.).

Figures 1, 2 and 3 illustrate lesions of steatohepatitis in cases of primary biliary cirrhosis, α-1-AT, and hepatitis C, respectively.

A andB, AMA-positive PBC. Many of the lesions of steatohepatitis, including mixed steatosis, ballooning, and mixed lobular acute and chronic inflammation are noted in the hematoxylin and eosin stain (A); the trichrome section (B) shows the characteristic persinusoidal fibrosis in zone 3 (upper left). The portal tract (lower right) is also expanded by fibrosis, presumably due to the primary biliary cirrhosis (A, H&E, 20 ×;B, Masson’s trichrome, 10 ×).

Following the clinical chart review, three distinct patient groups became evident: Group 1, patients with clinical and serologic diagnosis of hepatitis C (n = 54); Group 2, patients with hepatitis C and historical past or current use of >80g/d alcohol (n = 20); and Group 3, patients clinically diagnosed with other, non-hepatitis C, forms of liver disease (totaln = 11), as noted. All patients in Groups 1 and 3 consumed less than 10g/day of alcohol.

Table 2 is a summary of pertinent histologic findings in the three groups. Steatosis and perisinusoidal fibrosis were found in all biopsies, as defined by inclusion criteria for the study. Steatosis was predominantly macrovesicular and noted to involve >33% (i.e., Grades 2 and 3) in 50%, 60% and 64% in biopsies from Groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively (P = n.s.). Mean steatosis scores were 1.8 in hepatitis C genotype 3 and 1.72 in patients with all other hepatitis C genotypes. Steatosis was predominantly noted in acinar zone 3 in 33.3%, 43.8%, and 40% of the non-cirrhotic biopsies in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and more diffusely in all other biopsies. Mallory’s hyaline, although noted in biopsies from all groups, was documented more commonly, but not statistically significantly, in the biopsies from Group 2, hepatitis C + alcohol (57%), compared with Group 1, non-alcoholic hepatitis C patients (40%), and Group 3, nonalcoholic, non-hepatitis C biopsies (36%).

Histologic evidence of cirrhosis was noted in 26%, 25%, and 27% of biopsies for Groups 1, 2, and 3 (P = n.s.). In the cirrhotic biopsies, Mallory’s hyaline was noted in 53%, 75% and 25% respectively.

Table 3 summarizes the clinical findings in the three patient groups. Overall, significant differences in the proportion of men in each group were not found. The frequency of obesity (as defined by BMI of >30) was 75%, 60%, and 33% in Groups 1, 2, and 3 (P = n.s.); the “overweight” body mass index range of 25–30 was noted in 19%, 27% and 67%, respectively (P = n.s.). Thus, BMI ranges above ideal body weight were noted in 94%, 87% and 100% of patients within the 3 groups. Diabetes, as defined by prior clinical documentation of disease, was found in 29% of all patients but trended toward being greater in hepatitis C Groups 1 (35%) and 2 (25%) than in non-hepatitis C Group 3 (8%). In addition, diabetes was found in 8/23 (35%) with cirrhosis, and 17/62 (27%) without cirrhosis (P = n.s.). Hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia were noted in each group, but the prevalence of each was not statistically significantly different between groups. Hypertension was found in 30%, 25%, and 9%, in Groups 1, 2, and 3.

Table 4 summarizes the biochemical values and virologic results of each group. Hepatitis C genotype data was available in 51 patients; genotype 3 was documented in five patients, three of whom were in Group 2.

DISCUSSION

Liver biopsy evaluation is common in evaluation of many forms of liver disease and can be useful for characterizing the extent of necroinflammatory damage and architectural remodeling as well as detecting possible coexistent lesions (7, 19). In our biopsy practice, it was noticed that the lesions that have come to be accepted for steatohepatitis were seen in other forms of clinically-defined liver disease. This retrospective analysis of 34 months accrual of liver biopsies at Saint Louis University Hospital found that defined histologic features of steatohepatitis coexisted in up to 5% of non-allograft liver biopsies from patients with other liver diseases, even in the absence of significant alcohol consumption.

In contrast to alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, most other liver diseases can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical features and serologic tests (e.g., hepatitis C is diagnosed by antibody studies and viral RNA). Histologic evaluation of liver biopsy remains a significant component for the diagnosis of steatohepatitis, as there currently are no specific diagnostic laboratory tests (2, 20, 21). The histologic features of steatohepatitis are distinct (2, 4, 5, 6), and the types of inflammation and fibrosis generally do not overlap with the predominantly portal-based features of other chronic liver diseases (7). Also, in contrast to many other forms of chronic viral, metabolic, and cholestatic liver disease in which discriminate lesions may occur, the morphologic features of steatohepatitis in adults are similar, regardless of the underlying etiologies. These lesions include steatosis, mild mixed lobular acute and chronic inflammation, liver cell injury as manifested by ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, and intra-acinar perisinusoidal fibrosis; the lesions in the non-cirrhotic liver often predominate in acinar zone 3. Other features that may be seen include Mallory’s hyaline in ballooned hepatocytes, glycogenated nuclei, and lipogranulomas of varying size. Portal inflammation is typically mild, if present, and portal fibrosis and/or bridging fibrosis are not appreciated until later stages of the process have developed. It is well known that many of the histologic features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are similar to lesions of steatohepatitis of alcoholic origin (4, 22, 23, 24, 25). Pathologists, however, are not always privy to the history of possible alcohol use and often cannot reliably distinguish mild steatohepatitis of alcoholic and nonalcoholic etiologies by morphologic examination alone (4, 5, 6). Thus, in this study, no effort was made to exclude biopsies from patients who were subsequently noted to have a history of alcohol use during the chart review. It is interesting to note that the features of steatohepatitis were the same with regard to degree of steatosis, degree of fibrosis and presence or absence of Mallory’s hyaline in patients with hepatitis C consuming less than 10 g of alcohol per day and those consuming more than 80 g/day.

Steatosis is recognized as a common finding in liver biopsies (5). In chronic hepatitis C, macrovesicular steatosis has been reported in varying amounts, ranging from 31% to 70% in biopsies from adults and children (26, 27, 28, 29). In patients with hepatitis C, steatosis has been noted to be more common in infections with genotype 3(30, 31, 32, 33) and may be associated with increased fibrosis (31, 34). In this study, we found that of the 51 patients with hepatitis C for whom genotype information was available, only 10% were infected with genotype 3. The true prevalence of genotype 3 hepatitis C infection in our referral population is not known, thus the significance of this finding is unknown. Additionally, investigators have considered hepatocellular steatosis as related to obesity and not necessarily due to hepatitis C (35), whereas others have proposed that steatosis in hepatitis C is a manifestation of viral cytopathic effect (32, 36).

At the current time, all factors that may result in steatohepatitis are not well known, but obesity and the related metabolic consequences of insulin resistance have been identified as significant risk factors in large proportions of affected populations (21, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43). Likewise, the concurrence of diabetes and hepatitis C is an area of active investigation (44). It is significant therefore that in the current study, 66% of all patients studied were obese, while 26% were considered overweight and 29% had evidence of diabetes. Both obesity and diabetes were more often found in the two groups with chronic hepatitis C, than the group with non-hepatitis C forms of liver disease.

In the current study, inclusion criteria mandated that all of the biopsies showed not only steatosis but also perisinusoidal fibrosis, as this type of fibrosis is not considered a characteristic feature of other chronic necroinflammatory liver diseases (7). Perisinusoidal fibrosis, particularly in zone 3, is a common histologic indication of ongoing or past involvement by steatohepatitis of alcoholic or nonalcoholic etiologies (4, 5, 6, 22, 45, 46), but this form of fibrosis is not an identified characteristic feature of uncomplicated hepatitis C infection, as noted in studies that have compared histologic lesions of hepatitis C with and without steatohepatitis (47, 48, 49). Therefore, the presence of perisinusoidal fibrosis was a required histopathologic finding for inclusion in this study.

Recently, it has been suggested that the progression of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C is related to increased body mass and histologic evidence of steatosis (31, 34, 50, 51, 52). Most of these studies correlated increased portal-based fibrosis with steatosis (31, 34, 52) and were not clearly focused on lesions of concurrent steatohepatitis. In our study, the aim was to document coexistence of steatohepatitis utilizing accepted criteria with other forms of liver disease, and thus, we were not evaluating the possibility of progression of fibrosis in these patients.

When compared with all other forms of liver disease, the coexistence of steatohepatitis in our series of 85 patients was not proportionately greater in terms of statistical significance in patients with hepatitis C compared with other forms of liver disease. An interpretation of this result is that these are two common liver diseases (53, 54), which sometimes overlap by chance rather than a proclivity for steatohepatitis to be seen with a particular form of liver disease.

Limitations in the current study include that it is a retrospective review, is based on biopsies from patients referred to a large academic referral practice of liver disease, and includes a relatively small number of biopsies. However, because of the stringent histologic entry criteria for inclusion in the study to include only cases with evidence of perisinusoidal fibrosis in addition to the other lesions of steatohepatitis, our results quite possibly underestimate the actual concurrence of steatohepatitis with other forms of chronic liver disease. This certainly may be true when one considers the observations that cryptogenic cirrhosis, in which diagnostic histopathologic lesions of ongoing disease are no longer present, may be due in part to previous nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (55).

In conclusion, we have documented cases in which a liver biopsy done for a clinically-defined liver disease also showed the distinct, diagnostic histopathologic features of steatohepatitis. This finding was noted in biopsies from patients with chronic hepatitis C as well those with several other forms of chronic liver disease. Although alcohol use of >80 g/day was noted in a small proportion of cases, in the remainder alcohol use was reported as <10g/d and therefore would not be attributed as the underlying cause of the histologic lesions. The frequency of such concurrence may reflect the frequency with which steatohepatitis is present in our population, rather than a predisposition to occur in a certain form of liver disease. Further study is required to evaluate the significance of concurrent lesions in liver disease patients with regard to progression of the two diseases.

References

Baldridge AD, Perezatayde AR, Graemecook F, Higgins L, Lavine JE . Idiopathic steatohepatitis in childhood—a multicenter retrospective study. J Pediatr 1995; 127: 700–704.

Brunt EM . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: definition and pathology. Semin Liver Dis 2001; 21: 3–16.

Cortez-Pinto H, Chatham J, Chacko VP, Arnold C, Rashid A, Diehl AM . Alterations in liver ATP homeostasis in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. JAMA 1999; 282: 1659–1664.

Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1980; 55: 434–438.

Burt AD, Mutton A, Day CP . Diagnosis and interpretation of steatosis and steatohepatitis. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998; 15: 246–258.

Ludwig J, McGill DB, Lindor KD . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997; 12: 398–403.

Ishak KG . Chronic hepatitis: morphology and nomenclature. Mod Pathol 1994; 7: 690–713.

Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G . Occult hepatitis B infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 322–326.

Fong TL, DiBisceglieAM, Waggoner JG, Banks SM, Hoofnagle JH . The significance of antibody to hepatitis C virus in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 1991; 14: 64–67.

Zarski JP, Bohn B, Bastie A, Pawlotsky JM, Baud M, Bostbezequx F, et al. Characteristics of patients with dual infection by hepatitis B and C viruses. J Hepatol 1998; 28: 27–33.

Pessione F, Degos F, Marcellin P, Duchatelle V, Njapoum C, Martinotpeignoux M, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption on serum hepatitis C virus RNA and histological lesions in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1998; 27: 1717–1722.

Degos F . Hepatitis C and alcohol. J Hepatol 1999; 31: 113–118.

Bacon BR, Olynyk JK, Brunt EM, Britton RS, Wolff RK . HFE genotype in patients with hemochromatosis and other liver diseases. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 953–962.

Bonkovsky HL, Obando JV . Role of HFE gene mutations in liver diseases other than hereditary hemochromatosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 1999; 1: 30–37.

George DK, Powell LW, Losowsky MS . The haemochromatosis gene: a co-factor for chronic liver diseases? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 14: 745–749.

Brunt EM, Tavill AS, Bacon BR . A 49-year-old man with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency and abnormal iron study results. Semin Liver Dis 1996; 16: 97–101.

Brunt EM, Janney CG, DiBisceglieAM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2467–2474.

Scheuer PJ . Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol 1991; 13: 372–374.

Brunt EM . Liver biopsy interpretation for the gastroenterologist. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2000; 2: 27–32.

James O, Day C . Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: another disease of affluence. Lancet 1999; 353: 1634–1636.

Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Med Clin North Am 1996; 80: 1147–1166.

Diehl AM, Goodman Z, Ishak KG . Alcohollike liver disease in nonalcoholics. A clinical and histologic comparison with alcohol-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology 1988; 95: 1056–1062.

Lee RG . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a study of 49 patients. Hum Pathol 1989; 20: 594–598.

Itoh S, Yougel T, Kawagoe K . Comparison between nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1987; 82: 650–654.

Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ . Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 1413–1419.

Gerber MA, Krawczynski K, Alter MJ, Sampliner RE, Margolis HS . Histopathology of community acquired chronic hepatitis C. The Sentinel Counties Chronic Non-A, Non-B Hepatitis Study Team. Mod Pathol 1992; 5: 483–486.

Scheuer PJ, Ashrafzadeh P, Sherlock S, Brown D, Dusheiko GM . The pathology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 1992; 15: 567–571.

Lefkowitch JH, Schiff ER, Davis GL, Perrillo RP, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC, et al. Pathological diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter comparative study with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 1993; 104: 595–603.

Badizadegan K, Jonas MM, Ott MJ, Nelson SP, Perezatayde AR . Histopathology of the liver in children with chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Hepatology 1998; 28: 1416–1423.

Adinolfi LE, Utili R, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Rosario P, Mormone G et al. Relationship between genotypes of hepatitis C virus and histopathological manifestations in chronic hepatitis C patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 299–304.

Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Ruggiero G . Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology 2001; 33: 1358–1364.

Rubbia-Brandt L, Quadri R, Abid K, Giostra E, Male PJ, Mentha G, et al. Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J Hepatol 2000; 33: 106–115.

Mihm S, Fayyazi A, Hartmann H, Ramadori G . Analysis of histopathological manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with respect to virus genotype. Hepatology 1997; 25: 735–739.

Hourigan LF, Macdonald GA, Purdie D, Whitehall VH, Shorthouse C, Clouston A, et al. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C correlates significantly with body mass index and steatosis. Hepatology 1999; 29: 1215–1219.

Fiore G, Fera G, Napoli N, Vella F, Schiraldi O . Liver steatosis and chronic hepatitis C—a spurious association. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8: 125–129.

Moriya K, Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Ishibashi K, Matsuura Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces hepatic steatosis in transgenic mice. J Gen Virol 1997; 78: 1527–1531.

Tankurt E, Biberoglu S, Ellidokuz E, Hekimsoy Z, Akpinar H, Comlekci A, et al. Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 1999; 31: 963.

Sheth SG, Gordon FD, Chopra S . Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126: 137–145.

Chitturi S, Farrell GC . Etiopathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 2001; 21: 27–41.

Day CP, James OF . Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology 1998; 114: 842–845.

Sanyal AJ, Campbell-Sargent C, Mirshahi F, Rizzo WB, Contos MJ, Sterling RK, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 1183–1192.

Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS, Marceau S, Simard S, Thung SN, et al. Liver pathology and the metabolic syndrome X in severe obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84: 1513–1517.

Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med 1999; 107: 450–455.

Mehta SH, Brancati FL, Sulkowski MS, Strathdee SA, Szklo M, Thomas DL . Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among persons with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Hepatology 2001; 33: 1554.

Falchuk KR, Fiske SC, Haggitt RC, Federman M, Trey C . Pericentral hepatic fibrosis and intracellular hyalin in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 1980; 78: 535–541.

French SWN, J, Shitabata P, et al. Pathology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 1993; 13: 154.

Kyriacou E, Simmonds P, Miller EK, Bouchier IAD, Hayes PC, Harrison DJ . Liver biopsy findings in patients with alcoholic liver disease complicated by chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7: 331–334.

Rogers DW, Lee CH, Pound DC, Kumar S, Cummings OW, Lumeng L . Hepatitis C virus does not cause nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 1992; 37: 1644–1647.

Uchimura Y, Sata M, Kage M, Abe H, Tanikawa K . A histopathological study of alcoholics with chronic HCV infection—comparison with chronic hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. Liver 1995; 15: 300–306.

Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Purdie DM, Macdonald GA, Pandeya N, Shorthouse C, et al. Steatosis and chronic hepatitis C: analysis of fibrosis and stellate cell activation. J Hepatol 2001; 34: 314–320.

McCullough AJ, Falck-Ytter Y . Body composition and hepatic steatosis as precursors for fibrotic liver disease. Hepatology 1999; 29: 1328–1330.

Wong VS, Wight DGD, Palmer CR, Alexander GJM . Fibrosis and other histological features in chronic hepatitis C virus infection—a statistical model. J Clin Pathol 1996; 49: 465–469.

Lauer GM, Walker BD . Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 41–52.

Falck-Ytter Y, Younossi ZM, Marchesini G, McCullough AJ . Clinical features and natural history of nonalcoholic steatosis syndromes. Semin Liver Dis 2001; 21: 17–26.

Caldwell SH, Oelsner DH, Iezzoni JC, Hespenheide EE, Battle EH, Driscoll CJ . Cryptogenic cirrhosis: clinical characterization and risk factors for underlying disease. Hepatology 1999; 29: 664–669.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunt, E., Ramrakhiani, S., Cordes, B. et al. Concurrence of Histologic Features of Steatohepatitis with Other Forms of Chronic Liver Disease. Mod Pathol 16, 49–56 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000042420.21088.C7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000042420.21088.C7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fatty liver is associated with significant liver inflammation and increases the burden of advanced fibrosis in chronic HBV infection

BMC Infectious Diseases (2023)

-

Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with kidney disease

Nature Reviews Nephrology (2022)

-

Association between telomere length and hepatic fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Detection of DNA damage response in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via p53-binding protein 1 nuclear expression

Modern Pathology (2019)

-

Natural History of Patients Presenting with Autoimmune Hepatitis and Coincident Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2016)