Abstract

In non-neoplastic tissues, the expression of protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5), a member of the ubiquitin hydrolase family of proteins, is confined to neural and neuroendocrine cells. Although it has been claimed that PGP 9.5 is a specific marker of neural and/or nerve sheath differentiation in human tumors, careful review of the literature suggests that relatively few nonneural or nerve sheath tumors have been studied. Prompted by our recent observation of a PGP 9.5–positive malignant fibrous histiocytoma, we undertook a study of PGP 9.5 expression in a large group of well-characterized mesenchymal neoplasms. Sections from 95 mesenchymal tumors were retrieved from our archives and immunostained for PGP 9.5 using standard avidin-biotin complex technique and heat-induced epitope retrieval. Scoring was as follows: negative, 1+ (<10–25% of cells), 2+ (25–50% of cells), and 3+ (>50% of cells). Normal nerves and fibrous tissue were internal positive and negative controls, respectively. Positive immunostaining was seen in 80/95 (84%) of cases. Positive results by tumor subtype were as follows: (1) nerve sheath tumors: malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (7/10), neurofibromas (10/10), and perineuriomas (3/3); (2) (Myo) fibroblastic tumors: malignant fibrous histiocytoma (18/20), low-grade fibromyxoid sarcomas (8/9), fibromatoses (7/7), and desmoplastic fibroblastomas (2/2); (3) vascular tumors: angiosarcomas (4/4), hemangioendotheliomas (3/5), and hemangiomas (3/4); and (4) other non-nerve sheath tumors: pleomorphic liposarcoma (4/4), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (2/5), rhabdomyosarcomas (2/2), synovial sarcomas (8/8), melanomas (1/2). All positive cases were 2–3+ except 6 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, 1 neurofibroma, 3 malignant fibrous histiocytoma, 2 low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and 1 dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Positive staining was seen in normal smooth muscle and germinal centers in addition to nerves. We conclude that in this, the largest study to date of PGP 9.5 expression in mesenchymal neoplasms, we have found strong (2–3+) expression in the vast majority of nonneural or nerve sheath neoplasms studied. Although PGP 9.5 is a sensitive neural/nerve sheath marker, it is essentially totally nonspecific for diagnostic purposes. It is possible that our findings reflect cross-reactivity of the 13C4 clone with epitopes present on other ubiquitin hydrolases. Alternatively, PGP 9.5 expression may be aberrantly up-regulated in a variety of mesenchymal neoplasms.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5), also known as ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase-1 (UCH-L1), is a 27-kDa protein originally isolated from whole brain extracts (1). Although PGP9.5 expression in normal tissues was originally felt to be strictly confined to neurons and neuroendocrine cells (2), it has been subsequently documented in distal renal tubular epithelium, spermatogonia, Leydig cells, oocytes, melanocytes, prostatic secretory epithelium, ejaculatory duct cells, epididymis, mammary epithelial cells, Merkel cells, and dermal fibroblasts (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

In the field of diagnostic surgical pathology, PGP9.5 has enjoyed modest fame as a purportedly specific marker of putative neural and “neuroectodermal” tumors, such as neuroendocrine carcinomas/carcinoids (11, 12), primitive neuroectodermal tumors and neuroblastomas (13, 14, 15), granular cell tumors (16, 17), cellular neurothekeomas (18), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (19). Recently, however, doubt has been cast on the “neuroectodermal” specificity of PGP9.5, as its expression has been documented at both the RNA and protein level in a variety of non-neuroendocrine carcinomas, including those of the breast (9), kidney (6), prostate (5), pancreas (20), lung (21, 22), and colon (23).

Prompted by our recent observation of a PGP9.5-positive myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma, we undertook a study of PGP9.5 expression in a large group of well-characterized mesenchymal neoplasms.

METHODS

Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded blocks from 95 mesenchymal tumors were retrieved from the archives of Emory University, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and of one of the authors (ALF). These cases included malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (10), neurofibromas (10), perineuriomas (3), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (20), low-grade fibromyxoid sarcomas (9), fibromatoses (7), desmoplastic fibroblastomas (2), angiosarcomas (4), epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas (3), hobnail hemangioendotheliomas (2), hemangiomas (including spindle cell hemangioma) (4), pleomorphic liposarcomas (4), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (5), rhabdomyosarcomas (2), synovial sarcomas (8), and melanomas (2). Cases diagnosed as “malignant fibrous histiocytoma” were pleomorphic sarcomas that lacked any evidence of specific differentiation, after careful light microscopy and immunohistochemical study.

For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized, hydrated, 4-μm formalin-fixed sections were immunostained with a monoclonal antibody to PGP9.5 (clone 13C4, 1:100; Biomeda Corporation, Foster City, CA). The antibody conditions had been optimized previously at UAMS, using normal nerves and surrounding nonneural tissues as internal positive and negative controls, respectively. External negative controls consisted of substitution of normal mouse serum for the primary antibody. Sections were subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval using a pressure cooker with target retrieval buffer (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, CA) for 20 minutes. A 1:100 dilution of the antibody solution and appropriate reagents from the LSAB2 detection kit (DAKO) were used on the DAKO automated immunostainer. Antigens were localized using an avidin-biotin method with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. The tumors were scored as “negative” (<5% of cell positive), “1+” (6–25% of cells positive), 2+ (26–50% of cells positive), and 3+ (>51% of cells positive). In all positive cases, PGP9.5 was expressed in a cytoplasmic pattern.

RESULTS

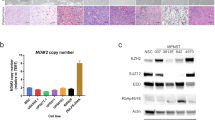

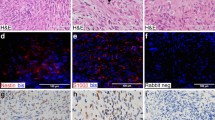

The immunohistochemical results are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, 80 of 95 (84%) cases expressed PGP9.5, with 2–3+ positivity in 67 cases (71%). With regard to the nerve sheath tumors, PGP9.5 was expressed by 20 of 23 (87%) cases, including all neurofibromas and perineuriomas, and 70% of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (Fig. 1A–D). However, PGP9.5 was also expressed by 60 of 72 (83%) non-nerve sheath tumors (Fig. 2A–H). In fact, only dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans were positive <50% of the time, with expression in 2 of 5 (40%) cases studied (Fig. 3A–B).

Among normal tissues, PGP9.5 was consistently expressed by normal axons (Fig. 4A), ganglion cells, and smooth muscle, as well as by lymphoid germinal centers (Fig. 4B). No expression was seen in other tissues.

DISCUSSION

PGP9.5 was first isolated from human whole-brain extracts by Jackson and Thompson (1) and Doran et al. (24) using high-resolution two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. PGP9.5 is expressed at approximately 50-fold greater concentration in the brain than in other tissues and comprises approximately 1–5% of total soluble brain proteins (1). Although the function of PGP9.5 was originally unknown, it was subsequently shown to be identical to ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolase 1 (UCHL1), an enzyme originally identified in bovine thymus (25). The PGP9.5/UCHL1 gene is located on chromosome 4p14 (26). The ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolases are a group of thiol proteases critical for the salvage of ubiquitin, the removal of small peptides from polyubiquitin complexes and cotranslational processing of ubiquitin gene products (27). Ubiquitin is a small protein that plays critical roles in the identification and removal of proteins targeted for degradation. The modification of proteins by ubiquitination and deubiquitination is important in many different cellular pathways, including (but not limited to) cell cycle regulation, cellular response to stress, and DNA repair (28).

As noted above, PGP9.5 was initially identified in neurons and was initially thought to be neuron specific. However, the first major survey of PGP9.5 expression in human tissues, by Thompson et al. (2), noted expression not only in neurons but also in melanocytes and a wide variety of neuroendocrine cells including anterior pituicytes, thyroid parafollicular cells, pancreatic islet cells, and adrenal medullary cells. These seminal observations appear to have given rise to the widely repeated statement that PGP9.5 expression is restricted to cells of neuroectodermal derivation. It it important to note, however, that PGP9.5 expression has been convincingly documented in a large number of nonneuroectodermally derived normal tissues, including smooth muscle, the distal renal tubule, spermatagonia, Leydig cells, oocytes, melanocytes, prostatic secretory epithelium, ejaculatory duct cells, epididymis, mammary epithelial cells, Merkel cells, and dermal fibroblasts (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

In the arena of tumor pathology, PGP9.5 was first identified as a sensitive marker of neuroendocrine tumors by Rode and colleagues, who noted PGP9.5 expression in the great majority of pituitary adenomas, medullary carcinomas of the thyroid, pancreatic islet cell tumors, pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas, neuroblastomas, and carcinoids studied (12). PGP9.5 expression was also noted by these investigators in a subset of melanocytic tumors and granular cell tumors, but not in a small number of nonneuroendocrine carcinomas and lymphomas. Several groups have subsequently confirmed PGP9.5 expression to be a sensitive marker of a variety of neuroendocrine neoplasms of various sites and degrees of differentiation (11, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36). Three studies have found PGP9.5 to be expressed in the overwhelming majority of small, round cell tumors with presumed neural/neuroectodermal differentiation, including neuroblastomas and primitive neuroectodermal tumors/Ewing sarcoma (13, 14, 15, 37). However, only a very small number of non-neural/neuroectodermal round cell tumors has been evaluated in these studies, and it is important to note that PGP9.5 expression has been documented by immunohistochemistry in nephroblastoma (13) and by Northern blot analysis in rhabdomyosarcomas (14). PGP9.5 expression has also been documented in some tumors with debatable neural or neuroendocrine differentiation, such as extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (38) and gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumor (GANT) (39). It is noteworthy that PGP 9.5 expression has also been convincingly shown at both the protein and gene level in nonneuroendocrine carcinomas of the breast (9), kidney (6), prostate (5), pancreas (20), lung (21, 22), and colon (23).

It is somewhat unclear where the concept of PGP9.5 as a relatively specific marker of nerve sheath tumors developed, as its expression has not been documented in endoneurial, perineurial, or epineurial supporting cells (e.g., Schwann cells, perineurial cells, etc.). In reviewing the literature, there is some suggestion that the expression of PGP9.5 in “nerve fibers” has been misinterpreted as evidence of expression in “nerves,” as opposed to neurons and their processes (16, 18, 19). With regard to tumors of putative nerve sheath origin, PGP9.5 expression has been documented in all granular cell tumors (16, 17), in 15 of 16 (94%) malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, including both spindled and epithelioid variants (19), and in 19 of 28 (68%) neurothekeomas (18, 40). The two studies of neurothekeoma, by Calonje et al. (40) and Wang et al. (18), have reported striking dissimilar results, with no expression noted by Calonje et al. (40) in 9 cellular neurothekeomas and with positive expression reported by Wang et al. (18) in 12 cellular, 4 intermediate, and 3 myxoid neurothekeomas. It is conceivable that these differences are related to the use of a polyclonal antibody without epitope retrieval in the Calonje et al. (40) study, as compared with a monoclonal antibody plus epitope retrieval in the study of Wang et al. (18). Again, as with small, round cell tumors, only a small number of expected negatives have been analyzed for PGP9.5 expression. Despite this, PGP9.5 expression has been documented in dermatofibromas, juvenile xanthogranulomas, leiomyomas, synovial sarcomas, and leiomyosarcomas, but not in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (18, 19).

In this context, then, it is perhaps not surprising that we have found PGP9.5 expression in a remarkably broad range of mesenchymal tumors, including those with fibroblastic, adipocytic, endothelial, muscular, and uncertain (e.g., synovial sarcoma) lines of differentiation. Although our study did not exhaustively analyze every type of mesenchymal tumor that might conceivably enter the differential diagnosis of a nerve sheath tumor (e.g., leiomyosarcomas, fibrosarcomas), we believe that our results convincingly make the case for the near-total lack of specificity of PGP9.5 expression. Obviously, in the context of this study and the above historical review, prior claims of “neuroectodermal” differentiation in tumors such as cellular neurothekeoma should be viewed with some skepticism.

What possible explanations are there for the widespread PGP9.5 expression that we have noted in this study? Conceivably our immunohistochemical technique could be resulting in entirely nonspecific false positives, although this seems highly unlikely given that we used the same 13C4 clone and comparable epitope retrieval methods as previous studies (16, 18), at a dilution that resulted in staining of normal neurons but not of surrounding connective tissue. It is possible that different results might be found with a different monoclonal antibody to PGP 9.5, although we doubt that these results would be significantly different, given that PGP9.5 expression has been documented at both the protein and gene level in diverse neoplasms (see above). It is also possible that cross-reactivity exists between epitopes present on PGP9.5 and other ubiquitin hydrolases, although this is not known to occur (Dr. Keith Wilkinson, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, personal communication). The most likely explanation for our findings, we believe, is that PGP9.5 expression is up-regulated in neoplasms, as compared with in their corresponding normal tissues. Evidence in support of this concept is provided by recent studies of PGP9.5 expression in lung and colonic carcinomas, in which both protein and mRNA expression was noted in many carcinomas but not in adjacent normal epithelia (22, 23). It has been shown recently that PGP9.5 gene expression may be up-regulated in HeLa cervical carcinoma cell lines, as compared with normal cervical epithelium, as a result of methylation of the CpG island of the promoter region (41), and it is certainly possible that similar mechanisms exist for up-regulation of PGP9.5 in mesenchymal neoplasms. Further study of the control of PGP9.5 expression in mesenchymal tumors is certainly warranted, especially as there has been recent evidence to suggest that patients with PGP9.5-positive tumors may also produce PGP9.5-reactive autoantibodies (21).

In conclusion, in this, the largest study to date of PGP9.5 expression in mesenchymal neoplasms, we have shown expression of PGP9.5 in the great majority of studied tumors, regardless of lineage. These results, as well as a careful review of the literature, strongly suggest that PGP9.5 expression is in no way specific for tumors of neural, neuroendocrine, or neuroectodermal origin. There does not appear to be a role for PGP9.5 immunohistochemistry in diagnostic neoplastic surgical pathology.

References

Jackson P, Thompson RJ . The demonstration of new human brain-specific proteins by high-resolution two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Neurol Sci 1981; 49: 429–438.

Thompson RJ, Doran JF, Jackson P, Dhillon AP, Rode J . PGP 9.5—a new marker for vertebrate neurons and neuroendocrine cells. Brain Res 1983; 278: 224–228.

Martin R, Fraile B, Peinado F, Arenas MI, Elices M, Alonso L, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of protein gene product 9.5, ubiquitin, and neuropeptide Y immunoreactivities in epithelial and neuroendocrine cells from normal and hyperplastic human prostate. J Histochem Cytochem 2000; 48: 1121–1130.

Hilliges M, Hellman M, Ahlstrom U, Johansson O . Immunohistochemical studies of neurochemical markers in normal human buccal mucosa. Histochemistry 1994; 101: 235–244.

Aumuller G, Renneberg H, Leonhardt M, Lilja H, Abrahamsson PA . Localization of protein gene product 9.5 immunoreactivity in derivatives of the human Wolffian duct and in prostate cancer. Prostate 1999; 38: 261–267.

D'Andrea V, Malinovsky L, Berni A, Biancari F, Biassoni L, Di Matteo FM, et al. The immunolocalization of PGP 9.5 in normal human kidney and renal cell carcinoma. G Chir 1997; 18: 521–524.

Olerud JE, Chiu DS, Usui ML, Gibran NS, Ansel JC . Protein gene product 9.5 is expressed by fibroblasts in human cutaneous wounds. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 111: 565–572.

Santamaria L, Martin R, Paniagua R, Fraile B, Nistal M, Terenghi G, et al. Protein gene product 9.5 and ubiquitin immunoreactivities in rat epididymis epithelium. Histochemistry 1993; 100: 131–138.

Schumacher U, Mitchell BS, Kaiserling E . The neuronal marker protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) is phenotypically expressed in human breast epithelium, in milk, and in benign and malignant breast tumors. DNA Cell Biol 1994; 13: 839–843.

Wilson PO, Barber PC, Hamid QA, Power BF, Dhillon AP, Rode J, et al. The immunolocalization of protein gene product 9.5 using rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal antibodies. Br J Exp Pathol 1988; 69: 91–104.

Bordi C, Pilato FP, D'Adda T . Comparative study of seven neuroendocrine markers in pancreatic endocrine tumours. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1988; 413: 387–398.

Rode J, Dhillon AP, Doran JF, Jackson P, Thompson RJ . PGP 9.5, a new marker for human neuroendocrine tumours. Histopathology 1985; 9: 147–158.

Carter RL, al-Sams SZ, Corbett RP, Clinton S . A comparative study of immunohistochemical staining for neuron-specific enolase, protein gene product 9.5 and S-100 protein in neuroblastoma, Ewing's sarcoma and other round cell tumours in children. Histopathology 1990; 16: 461–467.

Wang Y, Einhorn P, Triche TJ, Seeger RC, Reynolds CP . Expression of protein gene product 9.5 and tyrosine hydroxylase in childhood small round cell tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 551–558.

Banerjee SS, Agbamu DA, Eyden BP, Harris M . Clinicopathological characteristics of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of skin and subcutaneous tissue. Histopathology 1997; 31: 355–366.

Mahalingam M, LoPiccolo D, Byers HR . Expression of PGP 9.5 in granular cell nerve sheath tumors: an immunohistochemical study of six cases. J Cutan Pathol 2001; 28: 282–286.

Williams HK, Williams DM . Oral granular cell tumours: a histological and immunocytochemical study. J Oral Pathol Med 1997; 26: 164–169.

Wang AR, May D, Bourne P, Scott G . PGP9.5: a marker for cellular neurothekeoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1401–1407.

Hoang MP, Sinkre P, Albores-Saavedra J . Expression of protein gene product 9.5 in epithelioid and conventional malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001; 125: 1321–1325.

Tezel E, Hibi K, Nagasaka T, Nakao A . PGP9.5 as a prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 4764–4767.

Brichory F, Beer D, Le Naour F, Giordano T, Hanash S . Proteomics-based identification of protein gene product 9.5 as a tumor antigen that induces a humoral immune response in lung cancer. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 7908–7912.

Sasaki H, Yukiue H, Moriyama S, Kobayashi Y, Nakashima Y, Kaji M, et al. Expression of the protein gene product 9.5, PGP9.5, is correlated with T-status in non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001; 31: 532–535.

Yamazaki T, Hibi K, Takase T, Tezel E, Nakayama H, Kasai Y, et al. PGP9.5 as a marker for invasive colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 192–195.

Doran JF, Jackson P, Kynoch PA, Thompson RJ . Isolation of PGP 9.5, a new human neurone-specific protein detected by high-resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis. J Neurochem 1983; 40: 1542–1547.

Mayer AN, Wilkinson KD . Detection, resolution, and nomenclature of multiple ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterases from bovine calf thymus. Biochemistry 1989; 28: 166–172.

Edwards YH, Fox MF, Povey S, Hinks LJ, Thompson RJ, Day IN . The gene for human neurone specific ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCHL1, PGP9.5) maps to chromosome 4p14. Ann Hum Genet 1991; 55 (Pt 4): 273–278.

Wilkinson KD . Regulation of ubiquitin-dependent processes by deubiquitinating enzymes. FASEB J 1997; 11: 1245–1256.

Ciechanover A, Orian A, Schwartz AL . The ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic pathway: mode of action and clinical implications. J Cell Biochem 2000; 77: 40–51.

Inoue T, Shimono M, Takano N, Saito C, Tanaka Y . Merkel cell carcinoma of palatal mucosa in a young adult: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features. Oral Oncol 1997; 33: 226–229.

Kasai K, Kameya T, Kadoya K, Wada C . A pulmonary large cell carcinoma cell line expressing neuroendocrine cell markers and human chorionic gonadotropin alpha-subunit. Jpn J Cancer Res 1991; 82: 12–18.

Kasai K, Kameya T, Kawakubo Y, Sato Y, Wada C, Itoh H . Pulmonary large cell carcinoma expressing neuroendocrine markers: the morphological, biological, and neuroendocrine features of their cell lines and surgical cases. Jpn J Cancer Res 1992; 83: 1002–1010.

Bak J, Olsson Y, Grimelius L, Spannare B . Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. A case report and review of the literature. APMIS 1996; 104: 234–240.

Paties C, Zangrandi A, Vassallo G, Rindi G, Solcia E . Multidirectional carcinoma of the thymus with neuroendocrine and sarcomatoid components and carcinoid syndrome. Pathol Res Pract 1991; 187: 170–177.

Rode J, Dhillon AP, Cotton PB, Woolf A, O'Riordan JL . Carcinoid tumour of stomach and primary hyperparathyroidism: a new association. J Clin Pathol 1987; 40: 546–551.

Hamid QA, Bishop AE, Rode J, Dhillon AP, Rosenberg BF, Reed RJ, et al. Duodenal gangliocytic paragangliomas: a study of 10 cases with immunocytochemical neuroendocrine markers. Hum Pathol 1986; 17: 1151–1157.

Springall DR, Ibrahim NB, Rode J, Sharpe MS, Bloom SR, Polak JM . Endocrine differentiation of extra-pulmonary small cell carcinoma demonstrated by immunohistochemistry using antibodies to PGP 9.5, neuron-specific enolase and the C-flanking peptide of human probombesin. J Pathol 1986; 150: 151–162.

Ermisch B, Schwechheimer K . Protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 in diagnostic (neuro-) oncology. An immunomorphological study. Clin Neuropathol 1995; 14: 130–136.

Goh YW, Spagnolo DV, Platten M, Caterina P, Fisher C, Oliveira AM, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a light microscopic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and immuno-ultrastructural study indicating neuroendocrine differentiation. Histopathology 2001; 39: 514–524.

Shanks JH, Harris M, Banerjee SS, Eyden BP . Gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumours: a report of nine cases. Histopathology 1996; 29: 111–121.

Calonje E, Wilson-Jones E, Smith NP, Fletcher CD . Cellular. “neurothekeoma”: an epithelioid variant of pilar leiomyoma? Morphological and immunohistochemical analysis of a series. Histopathology 1992; 20: 397–404.

Bittencourt Rosas SL, Caballero OL, Dong SM, da Costa Carvalho Mda G, Sidransky D, Jen J . Methylation status in the promoter region of the human PGP9.5 gene in cancer and normal tissues. Cancer Lett 2001; 170: 73–79.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Vicky Givens, H.T., and Brandi Frank, H.T., for their histotechnical and immunohistochemical expertise and assistance with this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, L., Thomas, J., Lamps, L. et al. Protein Gene Product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) Is Not a Specific Marker of Neural and Nerve Sheath Tumors: An Immunohistochemical Study of 95 Mesenchymal Neoplasms. Mod Pathol 16, 963–969 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000087088.88280.B0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000087088.88280.B0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Immunohistochemical analysis of sensory corpuscles in human transplants of the anterior cruciate ligament

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2020)

-

Immunohistochemical Biomarkers of Gastrointestinal, Pancreatic, Pulmonary, and Thymic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Endocrine Pathology (2018)

-

Fluid biomarkers for mild traumatic brain injury and related conditions

Nature Reviews Neurology (2016)

-

Detection of the pan neuronal marker PGP9.5 by immuno-histochemistry and quantitative PCR in eutopic endometrium from women with and without endometriosis

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2015)

-

Cellular neurothekeoma: analysis of 37 cases emphasizing atypical histologic features

Modern Pathology (2014)