Abstract

Two genetically distinct habitat races of Drosophila melanogaster coexist in Brazzaville (Congo). One is the typical field type of Afrotropical populations, the other mainly breeds in beer residues in breweries. These two populations differ in their ethanol tolerance, in their allelic frequencies at several enzyme and microsatellite loci and in the composition of their cuticular hydrocarbons. The brewery population is quite similar to European temperate populations with regard to all these traits. Previous investigations of two morphological traits (ovariole number and sternopleural bristle number) failed to detect any difference between the two habitat races. Here we investigated other morphological traits (wing and thorax length, thorax pigmentation and female abdomen pigmentation). The reaction norms of these traits according to growth temperature were compared in the two Afrotropical habitat races and in a French temperate population. As expected, the French population was very different from the field African population: as a general rule, the brewery population (Kronenbourg) was intermediate in several aspects between the other two. We conclude that the strong selective forces that maintain the genetic divergence between the two habitat races also act on morphometrical traits, and the possible selective mechanisms are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drosophila melanogaster is a species adapted to use artificial man-made alcoholic food sources, and this correlates with a high Adh (alcohol dehydrogenase) activity and high tolerance of both ethanol and acetic acid (Chakir et al, 1993). In various parts of the world, this capacity has resulted in short-range genetic differences between populations using indoor fermented food sources and outdoor populations living in more natural habitats. Populations adapted to alcoholic food sources exhibit either a higher AdhF allelic frequency, or a higher tolerance of ethanol or acetic acid, or both traits simultaneously. This phenomenon has been observed in various parts of the world, including Australia (McKenzie and Parsons, 1974), Canada (Hickey and McLean, 1980), Spain (Alonzo-Moraga et al, 1985), tropical Africa (Vouidibio et al, 1989) and India (Karan et al, 1999b).

A particularly spectacular situation occurs in Brazzaville (Congo), where a brewery population is extremely different from field populations (Vouidibio et al, 1989; Capy et al, 2000). More specifically, flies collected from natural, countryside sites exhibit a low AdhF frequency (less than 5%), a low ethanol tolerance (6%) and a high frequency of the G6pdS (glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase) allele (more than 90%). Brewery populations are very different, with a high AdhF frequency (around 80%), a high ethanol tolerance (15%) and lower frequencies of the G6pdF (40%). Significant differences have also been observed for the Esterase-C locus and microsatellite markers (Capy et al, 2000). All these characteristics of the brewery population are analogous to those found in temperate French populations (Vouidibio et al, 1989; Capy et al, 2000; Haerty et al, 2002). This suggests that this population might be derived from a temperate population. Another clearcut difference between brewery and local field flies concerns the composition of cuticular hydrocarbons. The brewery population in Brazzaville is almost identical to European populations, especially with a predominance of 7–11 heptacosadiene in females. Flies collected from the outskirts of Brazzaville are typical of Afrotropical populations, with a predominance of 5–9 heptacosadiene (Haerty et al, 2002). Interestingly, in Brazzaville city the two habitat races cross-breed and produce hybrids, as demonstrated by the intermediate allozyme frequencies and ethanol tolerance values found in many samples collected in gardens (Vouidibio et al, 1989). In spite of such clear indications of gene flow between the two ecological races, we also have evidence of their persistence over time (Vouidibio et al, 1989).

These observations led to the hypothesis that after the breweries were constructed (around 1930), a European D. melanogaster propagule was accidentally introduced, proliferated in the brewery and founded the extant brewery race. There are some indications of sexual isolation between field and brewery flies (Capy et al, 2000, Haerty et al, 2002) but also, as stated above, strong evidence of introgression of African alleles into the brewery population. The fact that both habitat races have persisted over time certainly implies the presence of very strong and divergent selective pressures, which have yet to be clearly identified.

D. melanogaster is also known to exhibit great genetic differentiation with respect to morphological traits, and this variation is often arranged into long-range latitudinal clines (Capy et al, 1993). For example, temperate populations are bigger and have higher ovariole and bristle numbers. According to the propagule hypothesis, we might wonder whether the brewery population has kept some other characteristics from its temperate origin. Investigations of ovariole number (Delpuech et al, 1995) and sternopleural bristle number (Moreteau et al, 2003) failed to reveal any difference between the two habitat races, which both appeared to be typically African. These traits, which are strongly selected along latitudinal clines, are apparently not involved in resource utilization.

This interpretation may, however, not be valid for other morphometrical traits. In the present paper, we compare the two habitat races with regard to two kinds of quantitative traits, body size and body pigmentation, by comparing the reaction norms along a temperature gradient. The results are compared to those of a temperate French population. In contrast with previous conclusions for ovariole and bristle numbers, we found that the brewery population differs significantly from the field population and is always closer to the European population. We interpret these differences as a consequence of natural selective pressure, which maintains divergent morphometrical traits in the two habitat races.

Materials and methods

Populations and experimental flies

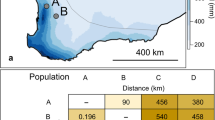

Wild adults were collected from two sites in the Brazzaville area (see map in Vouidibio et al, 1989): the Kronenbourg brewery and the country district of Loua. Allozyme electrophoreses confirmed that these samples corresponded to the two clearcut races previously identified (Vouidibio et al, 1989). These wild collected flies were brought to France to initiate isofemale lines. From each line, 10 pairs of laboratory-grown adults were randomly taken and used as parents for producing the next experimental generation. Experimental flies correspond to the second generation in the laboratory, avoiding any possible laboratory adaptation. These parents oviposited for a few hours at 20°C on a high-nutrient, killed yeast medium and the culture vials were then transferred to one of six constant temperatures (14, 17, 21, 25, 28 or 31°C). Population larval density was not accurately determined, but ranged between 100 and 200 adults per vial. The use of a high nutrient food prevents any significant impact of crowding on morphometrical traits (see Karan et al, 1999a).

For each population, 10 isofemale lines were investigated. The results were compared to those obtained, in a similar way, for 10 lines from a French population from Bordeaux. In this case, lines were investigated after four generations in the laboratory. We have evidence (Karan et al, 1999a) that the characteristics of the Bordeaux population remain stable in different years. For the purpose of the present comparison, we investigated only 10 lines from that population.

Traits measured

From each line and each growth temperature, we measured 10 randomly selected females. Total wing length was measured from the thoracic articulation to the apex, and thorax length from the neck to the tip of the scutellum. Micrometer units were transformed into mm × 100. Body pigmentation was analyzed by estimating visual phenotypic classes. On the thorax, the presence and intensity of a darker area with a trident shape (the thoracic trident) was scored on a four-point scale, from 0 for no pigmentation to 3 for a dark trident (see David et al, 1985). For the pigmentation of the abdomen, we estimated the relative extent of the black pigment on each of the last three tergites (segments 5, 6 and 7) of the females. A total of 10 phenotypic classes were used, scoring from 0 (completely yellow tergite) to 10 (completely black) (see David et al, 1990). For each trait and population, data are available for 600 females.

Data analysis

For each of the three populations compared, we analyzed the response curves of 10 lines grown at six different temperatures. Data were subjected to ANOVA with STATISTICA software. The shapes of the response curves (the reaction norms) were also investigated, and characteristic values for each line were calculated using previously defined techniques (David et al, 1997). Depending on the shape of the reaction norm, we used either quadratic or cubic adjustments. For the sake of simplicity, concave norms (eg wing and thorax length) were characterized by the coordinates of the maximum. The ordinate defines the maximum value (MV) of the trait calculated from the adjustment, and the abscissa the corresponding temperature of the maximum value (TMV). MV defines the quantitative value of the traits, while TMV defines its reactivity to temperature, that is, its plasticity (see David et al, 1997, 2003), and variations among lines are assumed to have a genetic basis. Convex norms were defined by the coordinates of the minimum. Decreasing sigmoid norms were defined by the coordinates of the inflexion point. Genetic correlations between different traits were calculated using family means (see Via, 1984; Gibert et al, 1998b).

Results

Reaction norms of body size traits

Average reaction norms of wing and thorax length are shown in Figure 1. Nonoverlapping confidence intervals demonstrate numerous significant differences, not only between the temperate Bordeaux and the two African populations, but also between the two African populations. Results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA in two steps. First, the three populations were compared, temperature and population being considered as fixed, and lines as a random, effect nested in populations. All effects and interactions were highly significant (ANOVA, not shown). Second, the two African populations were compared to each other using the same procedure (ANOVA, Table 1). A significant difference was found between the populations for the thorax (a higher average value in Kronenbourg), but no population–temperature interaction. For the wing, the results were the opposite: no difference was found between average values, but there was a strong population–temperature interaction: longer wings occurred in the Kronenbourg population at low temperature, whereas longer wings occurred in the Loua population at high temperature (see Figure 1).

The wing/thorax (W/T) ratio is also an interesting trait, since it is negatively related to wing loading and presumably to flight capacity (Pétavy et al, 1997). The W/T ratio exhibits a specific monotonically decreasing sigmoid reaction norm (David et al, 1994). Average reaction norms (Figure 2) and ANOVA analyses both detected differences among the three populations. Comparison of the two African populations (Table 1) showed that all effects and interactions were significant. The ratio in Loua is generally smaller than in Kronenbourg and Bordeaux populations except at 31°C.

Body size traits: characteristic values of the reaction norms

As seen in Figure 1, both wing and thorax lengths show concave reaction norms, with peak values at low temperature. Polynomial adjustments (David et al, 1997) of each line made it possible to calculate two characteristic values for each trait. A few isofemale lines could not be conveniently adjusted to a concave curve, producing a TMV outside the thermal development range. Such a phenomenon had already been observed for sternopleural bristle number (Moreteau et al, 2003). The data corresponding to these lines (three from Kronenbourg and three from Loua) have not been included in the statistics given in Table 2.

As expected, the MVs of both traits were highly heterogeneous when the large body size of the Bordeaux population was included in the analysis (ANOVA, Table 2). A significant difference between Loua and Kronenbourg was found for wing length only. For TMVs, only the ANOVA for thorax length revealed a significant heterogeneity between populations (Table 2). A more accurate comparison (Scheffé test) showed that Bordeaux had a significantly lower TMV than Loua, and that the value for Kronenbourg was intermediate between these two. This result corroborates previous studies: a higher TMV in a tropical than in a temperate population appears to be an adaptive change to a warmer environment (Morin et al, 1999). The differences in wing length, despite not being significant, also point to the same conclusion.

For the W/T ratio, the sigmoid decreasing shape of the norm makes it possible to calculate numerous characteristic values after a cubic adjustment (see David et al, 1997). We consider here only the coordinates of the inflexion point, namely the phenotype at the inflexion point (PIP) and the temperature at the inflexion point (TIP). It was not always possible to calculate relevant characteristic values for the 30 lines. We considered the distribution of TIP in the whole sample, and found that in 25 lines, it followed a unimodal distribution, with a mean of 21.02±0.71 (range 15.04–28.08°C). The five others were quite distinct from this main distribution, with TIPs below 7 or above 33°C, that is, more than four standard deviations from the mean. Two of these aberrant lines were found in Bordeaux, two in Kronenbourg and one in Loua (these lines were not included in the calculation of Table 2). Both PIP and TIP showed significant differences between populations. PIP was higher in Kronenbourg than in Loua, with an intermediate value in Bordeaux. For the TIP, a very different pattern was observed, with a higher temperature in Loua than in Kronenbourg (23.2 vs 18.4°C) and an intermediate value in Bordeaux.

Abdominal pigmentation: reaction norms and characteristic values

Average reaction norms of the three last abdomen segments (A5, A6 and A7) are shown in Figure 3. We can see that for segment 5, the three populations were almost the same (an interpretation confirmed by ANOVA), with an overall smoothly decreasing convex reaction norm. We therefore decided to exclude this segment from further analyses. Segments A6 and A7 exhibited monotonically decreasing norms, with obvious differences between the three populations. When the two African populations were compared (Table 1), all the direct effects and interactions were significant.

Figure 3 shows that on average the Loua population is the darkest, the Bordeaux population is the lightest and the Kronenbourg population is intermediate. Interestingly, the three populations are fairly close at low temperatures and diverge as the growth temperature is increased.

Since the two segments, A6 and A7, apparently provide the same information and, moreover, are known to be genetically highly correlated (Gibert et al, 2000), we added the two values and considered the sum A6+A7 (Figure 4). As for the W/T ratio, we analyzed the shape of the reaction norms after a cubic adjustment and here we show only the coordinates of the inflexion point (Table 3). Among the 20 African lines, it was not always possible to calculate these characteristic values. Considering the whole sample of 30 lines, we found that 24 isofemale lines followed a unimodal distribution, with a mean of 22.49±0.78 (range 11.07–27.42°C). The other six were quite distinct from this main distribution, with TIPs below 6.77 or above 41.42°C, that is, more than four standard deviations from the mean. Three of these aberrant lines were found in Kronenbourg and three in Loua. Without these lines, significant differences were found between Kronenbourg and Loua for PIP, with a darker phenotype in Loua. With regard to TIP, the highest temperature (24.4°C) was found in Kronenbourg and the lowest in Loua, but the difference was not significant. However, we see here the limits of the mathematical model, in that we had to eliminate too many lines that did not fit to this model. So the results from these adjustments are not used in the following discussion.

Thoracic trident pigmentation

For this trait, we know that the reaction norm is a convex curve with a minimum at an intermediate temperature (Gibert et al, 2000). Adaptive latitudinal clines, with a darker pigmentation in colder climates, have also been documented (David et al, 1985; Munjal et al, 1997). Findings for the three populations (Figure 5) confirmed these expectations for the shape of the curves and the darker pigmentation in Bordeaux. The Kronenbourg population is fairly similar to that of Bordeaux, and a comparison between the two African populations (Table 1) revealed that all effects and interactions were highly significant. We also calculated the coordinates of the minimum values (Table 3) for all lines.

The phenotype of minimum value (PminV) clearly distinguished Loua from either Kronenbourg or Bordeaux, although the temperature of minimum value did not differ in the three populations, averaging 25.2°C.

Genetic correlations between different traits

Our data have shown that the two African habitat races were genetically different for several quantitative traits related either to body size or pigmentation. This raises an important question: how many genetically independent traits are involved in this local differentiation? To answer this question, we calculated the genetic correlations between any pairs of traits, using family means as a variable (see Via, 1984; Gibert et al, 1998b). A correlation was calculated for each population and each temperature. ANOVA, applied after a z transformation, revealed no significant variation according to growth temperature. So the best estimate of a correlation, for a given population, is the mean coefficient averaged over six growth temperatures.

Average correlations are shown in Table 4. There was only one significant difference between populations (ANOVA): a highly significant positive value was found between wing length and thoracic trident in Bordeaux, vs values close to 0 in Loua and Kronenbourg. Among the six pairwise correlations that are considered, one is positive and highly different from zero: the wing–thorax correlation (0.64±0.06). This is consistent with previous investigations (David et al, 1994; Karan et al, 2000). The correlation between thorax length–abdomen pigmentation is positive and slightly greater than zero (r=0.22±0.07, P<0.05). From these observations, we may conclude that three sets of traits that differentiate Loua and Kronenbourg are almost completely independent: size traits (wing and thorax length), thoracic trident and abdomen pigmentation.

Discussion

The two habitat races of D. melanogaster in Brazzaville exhibit not only differences in allozyme loci, cuticular hydrocarbons and in physiological and behavioral traits (Vouidibio et al, 1989; Capy et al, 2000), but they also display significant differences in quantitative morphometrical traits, which are genetically independent, namely the traits of size (wing and thorax length), thoracic pigmentation and female abdomen pigmentation. Size and thorax pigmentation are known to exhibit latitudinal clines (David et al, 1985; Capy et al, 1993; Munjal et al, 1997) and presumably reflect climatic adaptation. This is not the case for abdomen pigmentation (in that there are no regular clines), although some genetic differences between geographic populations presumably also correspond to temperature adaptation (Gibert et al, 1996, 1998a). Interestingly, two other independent quantitative traits (ovariole and sternopleural bristle number), which also exhibit latitudinal clines, failed to discriminate between the Kronenbourg and Loua populations.

In almost all the cases in which we found a significant difference between the two habitat races, the Kronenbourg population appeared to be intermediate between the purely African population from Loua and the temperate population from Bordeaux. However, the magnitude of the difference was variable, depending on the trait investigated. For the thoracic trident, Kronenbourg was close to Bordeaux and very distant from Loua. For abdomen pigmentation, Kronenbourg was intermediate between the other two. For wing and thorax length, Loua and Kronenbourg were generally quite similar, and very distinct from Bordeaux. For the wing/thorax ratio, the main difference was found between Loua on the one hand and Kronenbourg and Bordeaux on the other.

The fact that we investigated the quantitative traits at various developmental temperatures has certainly permitted a better comparison of the three populations, and has revealed genotype/temperature interactions. For size traits, the divergence between populations was higher at low temperature, and diminished at high temperature (see Figures 1 and 2), whereas the reverse was true for abdomen pigmentation (Figures 3 and 4). There is no obvious explanation for such a difference. However, it should be remembered that in a previous comparison of wing length reaction norms of different species, we also found a convergence of the reaction norms at high temperatures (David et al, 1997). This general observation may reflect some internal constraint on wing development.

The analysis of the shape of the reaction norms of size traits has also revealed some interesting features. The fact that in Loua the temperature of maximum value of thorax length is higher than it is in Bordeaux suggests that natural selection affects not only trait values, but also their reaction norms. This observation corroborates previous conclusions based on Caribbean populations (Morin et al, 1999).

For abdomen pigmentation, a remarkable and unexpected observation is the dark pigmentation of the African field population. Previous investigations of the phenotypic plasticity of this trait revealed an overall lightening at higher growth temperatures. Such a phenomenon, which has been observed in various insect species, has given rise to a general interpretation: the thermal budget adaptive hypothesis (Gibert et al, 2000). A lighter body color, which reflects more light, is an adaptation to living in warmer places. The latitudinal clines in thoracic coloration fit this interpretation (David et al, 1985; Munjal et al, 1997). A comparison of abdomen pigmentation in French and Indian flies also revealed a lighter pigmentation in populations living in the warmer climate, such as Indian populations (Gibert et al, 1998a). The dark pigmentation observed on the abdomen of the Loua females is in clear contradiction to the thermal budget hypothesis. Several other observations suggest that dark abdomen pigmentation could be the rule among females of Afrotropical populations. This peculiarity could be related to some other adaptation, such as camouflage or mate recognition (Majerus, 1998) and more extensive investigations are needed.

Brazzaville is an equatorial city where temperature is stable all year round (average 25–26°C). When collecting flies in Kronenbourg and Loua, we confirmed that the temperatures were virtually the same in the two kinds of habitats. All ecological observations suggest that temperature is not the selective factor that maintains the quantitative differences between the two habitat races. One possibility, related to the propagule hypothesis already mentioned in Introduction, is that the brewery population has kept some temperate features because of the short evolutionary time since its foundation. This hypothesis is, however, unlikely, especially if we consider that very close similarity between Loua and Kronenbourg has been observed for two other clinal quantitative traits: ovariole and sternopleural bristle numbers.

An alternative hypothesis is that selective pressures, which are presumably related to habitat quality and larval resources, and which maintain the divergence between the two kinds of population, also act directly on the adult phenotypes. For example, a larger body size, a higher wing/thorax ratio, a darker pigmentation of the thorax and lighter pigmentation of the abdomen could be favored in the brewery environment. Although this hypothesis cannot be ruled out, we do not see, for the moment, why such a phenotypic selection could occur. It remains, however, possible that the quantitative trait genes, here selected, have other pleiotropic effects that could be the real target of selection.

A last possibility is the linkage hypothesis, which is that the genes that are the primary target of natural selection could be tightly linked to unknown quantitative trait loci, acting on body size and body pigmentation. A tight linkage would be able to slow down the process of homogenization between field and brewery populations, which certainly occurs for neutral genes. Further investigations may help us to choose between these scenarios.

A genetic divergence between populations of the same species adapted to different resources or habitat is often considered as a first step toward sympatric speciation (Via, 2001). Examples of this kind are increasing in number, as in apple maggot flies (Bush, 1969; Feder, 1998), pea aphids (Via, 1999, 2001) and Drosophila mojavensis (Etges and Ahrens, 2001). For the speciation process to be complete, some behavioral isolation needs to occur, and this is seen in Brazzaville (Capy et al, 2000; Haerty et al, 2002). The Brazzaville situation is, however, unique because populations did not evolve locally but are probably the consequence of an accidental introduction followed by an incomplete introgression, lack of panmixia and strong divergent selection.

If this hypothesis is correct, it must be assumed that the brewery population is adapted to the tropical environment for wing and thorax lengths but not for pigmentation traits. This suggests that traits related to size as well as ovariole and sternopleural bristle numbers rapidly evolved under the new conditions. This has already been observed in other species such as D. simulans on Japanese islands (Watada et al, 1986) and D. subobscura on the American continent (Huey et al, 2000).

References

Alonzo-Moraga A, Munoz-Serrano A, Rodero A (1985). Variation of alloenzyme frequencies in Spanish field and cellar populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Sel Evol 17: 435–442.

Antony C, Davis TL, Carlson DA, Pechiné JM, Jallon JM (1985). Compared behavioural responses of male Drosophila melanogaster to natural and synthetic aphrodisiacs. J Chem Ecol 11: 1617–1629.

Antony C, Jallon JM (1982). The chemical basis for sex recognition in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol 28: 873–880.

Bush GL (1969). Sympatric host races formation and speciation in frugivorous flies of the genus Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephridae). Evolution 23: 237–251.

Capy P, Pla E, David JR (1993). Phenotypic and genetic variability of morphometrical traits in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Genet Sel Evol 25: 517–536.

Capy P, Veuille M, Paillette M, Jallon JM, Vouidibio J, David JR (2000). Sexual isolation of genetically differentiated sympatric populations of Drosophila melanogaster in Brazzaville, Congo: the first step towards speciation? Heredity 84: 468–475.

Chakir M, Capy P, Pla E, Vouidibio J, David JR (1994). Ethanol and acetic acid tolerance in Drosophila melanogaster. Similar maternal effects in a cross between two geographic races. Genet Sel Evol 26: 29–37.

Chakir M, Peridy O, Capy P, Pla E, David JR (1993). Adaptation to alcoholic fermentation in Drosophila: a parallel selection imposed by environmental ethanol and acetic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 3621–3625.

David JR, Capy P, Gauthier JP (1990). Abdominal pigmentation and growth temperatures in Drosophila melanogaster: similarities and differences in the norms of reaction of successive segments. J Evol Biol 3: 429–445.

David JR, Capy P, Payant V, Tsakas S (1985). Thoracic trident pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster: differentiation of geographical populations. Genet Sel Evol 17: 211–223.

David JR, Gibert P, Gravot E, Pétavy G, Morin JP, Karan D, Moreteau B (1997). Phenotypic plasticity and developmental temperature in Drosophila: analysis and significance of reaction norms of morphometrical traits. J Therm Biol 22: 441–451.

David JR, Gibert P, Moreteau B (2003). Evolution of reactions norms. In: DeWitt TJ and Scheiner SM (eds) Phenotypic Plasticity. Functional and Conceptual Approaches, Oxford University Press: USA, in press.

David JR, Moreteau B, Gauthier JP, Petavy G, Stockel A, Imasheva AG (1994). Reaction norms of size characters in relation to growth temperature in Drosophila melanogaster: an isofemale lines analysis. Genet Sel Evol 26: 229–251.

Delpuech JM, Moreteau B, Chiche J, Pla E, Vouidibio J, David JR (1995). Phenotypic plasticity and reaction norms in temperate and tropical populations of Drosophila melanogaster: ovarian size and developmental temperature. Evolution 49: 670–675.

Etges WJ, Ahrens MA (2001). Premating isolation is determined by larval-rearing substrates in cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. V. Deep geographic variation in epicuticular hydrocarbons among isolated populations. Am Nat 158: 585–598.

Feder JL (1998). The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pommonella: flies in the face of conventional wisdom about speciation? In: Howard DJ, Berlocher SH (eds) Endless Forms: Species and Speciation, Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp 130–144.

Ferveur JF, Cobb M, Boukella H, Jallon JM (1996). World-wide variation in Drosophila melanogaster sex pheromone: behavioral effects, genetic bases and potential evolutionary consequences. Genetica 97: 73–80.

Gibert P, Moreteau B, David JR (2000). Developmental constraints on an adaptive plasticity: reaction norms of pigmentation in adult segments of Drosophila melanogaster. Evol Dev 2: 249–260.

Gibert P, Moreteau B, Moreteau JC, Parkash R, David JR (1998a). Light body pigmentation in Indian Drosophila melanogaster: a likely adaptation to a hot and arid climate. J Genet 77: 13–20.

Gibert P, Moreteau B, Scheiner SM, David JR (1998b). Phenotypic plasticity of body pigmentation in Drosophila: correlated variations between segments. Genet Sel Evol 30: 181–194.

Gibert P, Moreteau B, Moreteau C, David JR (1996). Growth temperature and adult pigmentation in two Drosophila sibling species: An adaptative convergence of reaction norms in sympatric populations? Evolution 50: 2346–2353.

Haerty W, Jallon JM, Rouault J, Capy P (2002). Reproductive isolation in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster in Brazzaville (Congo). Genetica 116: 215–224.

Hickey DA, McLean MD (1980). Selection for ethanol tolerance and ADH alloenzyme in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Res 36: 11–15.

Huey RB, Gilchrist GW, Carlson ML, Berrigan D, Serra L (2000). Rapid evolution of a geographic cline in size in an introduced fly. Science 287: 308–309.

Karan D, Morin JP, Gravot E, Moreteau B, David JR (1999a). Body size reaction norms in Drosophila melanogaster: temporal stability and genetic architecture in a natural population. Genet Sel Evol 31: 491–508.

Karan D, Morin JP, Gibert P, Moreteau B, Scheiner SM, David JR (2000). The genetics of phenotypic plasticity. IX. Genetic architecture, temperature, and sex differences in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 54: 1035–1040.

Karan D, Parkash R, David JR (1999b). Microspatial genetic differentiation for tolerance and utilization of various alcohols and acetic acid in Drosophila species from India. Genetica 105: 249–258.

Majerus ME (1998). Melanism. Evolution in Action. Oxford University Press: New York.

McKenzie JA, Parsons PA (1974). Microdifferentiation in a natural population of Drosophila melanogaster to alcohol in the environment. Genetics 77: 385–394.

Moreteau B, Gibert P, Delpuech JM, Pétavy G, David JR (2003). Phenotypic plasticity of sternopleural bristle number in temperate and tropical populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Res Camb 81: 25–32.

Morin JP, Moreteau B, Pétavy G, David JR (1999). Divergence of reaction norms of size characters between tropical and temperate populations of Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. J Evol Biol 12: 329–339.

Morin JP, Moreteau B, Petavy G, Parkash R, David JR (1997). Reaction norms of morphological traits in Drosophila: Adaptive shape changes in a stenotherm circumtropical species? Evolution 51: 1140–1148.

Munjal AK, Karan D, Gibert P, Moreteau B, Parkash R, David JR (1997). Thoracic trident pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster: latitudinal and altitudinal clines in Indian populations. Genet Sel Evol 29: 601–610.

Pétavy G, Morin JP, Moreteau B, David JR (1997). Growth temperature and phenotypic plasticity in two Drosophila sibling species: probable adaptive changes in flight capacities. J Evol Biol 10: 875–887.

Via S (1984). The quantitative genetics of polyphagy in an insect herbivore. II. Genetic correlations in larval performance within and among host plants. Evolution 38: 896–905.

Via S (1999). Reproductive isolation between sympatric races of pea aphids. I. Gene flow restriction and habitat choice. Evolution 53: 1446–1457.

Via S (2001). Sympatric speciation in animals: the ugly duckling grows up. TREE 16: 381–390.

Vouidibio J, Capy P, Defaye D, Pla E, Sandrin J, Csinka A et al (1989). Short range genetic structure of Drosophila melanogaster populations in an Afrotropical urban area and its significance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 8442–8446.

Watada M, Tobari YN, Ohba S (1986). Genetic differentiation in Japanese populations of Drosophila simulans and Drosophila melanogaster. Jpn J Genet 61: 253–269.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two unknown referees for their helpful and encouraging comments on the previous version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haerty, W., Gibert, P., Capy, P. et al. Microspatial structure of Drosophila melanogaster populations in Brazzaville: evidence of natural selection acting on morphometrical traits. Heredity 91, 440–447 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800305

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800305

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Drosophila as models to understand the adaptive process during invasion

Biological Invasions (2016)

-

Isofemale lines in Drosophila: an empirical approach to quantitative trait analysis in natural populations

Heredity (2005)

-

Microclinal variation for ovariole number and body size in Drosophila melanogaster in ?Evolution Canyon?

Genetica (2005)