Abstract

Glucosinolates are plant secondary metabolites composed of a thioglucose group and an amino acid side-chain. They occur in the Brassicaceae and related families. A wide variety of glucosinolates exists owing to modification of the side-chain structure. Following tissue damage, myrosinase enzymes catalyse the decomposition of glucosinolates to a variety of volatile and nonvolatile products. The genetic control of concentration and side-chain modification of aliphatic glucosinolates, which have side-chains derived from methionine, are simple and well known from work on Arabidopsis and Brassica crops. In controlled conditions in the laboratory or in field trials, many aliphatic glucosinolates, or their degradation products, affect the behaviour of herbivores. For these reasons, we suggest that polymorphism for aliphatic glucosinolates in natural populations offers an attractive system for the study of ecological genetics of plant–herbivore interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aliphatic glucosinolates (hereafter ‘glucosinolates’) are plant secondary metabolites derived from methionine. They occur in the Capparales, which includes several commercially important crops, and a few unrelated species. Glucosinolates are hydrolysed by plant myrosinase enzymes when tissue is damaged to produce a range of volatile and nonvolatile products depending on plant genotype and environmental conditions.

Glucosinolates are of considerable interest to plant breeders. Presence of 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl glucosinolate in the seeds of oilseed crops reduces the quality of meal left after oil extraction. Effects on livestock include thyroid, liver and kidney problems. Also, certain breakdown products of glucosinolates can cause goitre in farm animals (the trivial name of 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl glucosinolate is progoitrin), but there is no evidence that glucosinolates are goitrogenic in humans (Mithen, 2001). ‘Double low’ varieties of oilseed rape have been bred to have seeds with low amounts of glucosinolates and erucic acid, an antinutritional factor in humans (e.g. Friedt & Luhs, 1998). Glucosinolate degradation products are probably beneficial to humans because they protect against cancer by stimulating enzymes that metabolize xenobiotic chemicals (Mithen, 2001). Glucosinolates and their degradation products also affect the behaviour of serious economic pests of oilseed Brassica crops (see below) and manipulation of glucosinolates may offer new strategies for crop protection.

The economic importance of glucosinolates has stimulated much research into glucosinolate biosynthesis and the effects of glucosinolate phenotype on herbivore behaviour. This research has been carried out mostly from an agricultural perspective, but it has created an excellent set of resources for ecological geneticists interested in plant–herbivore interactions.

First, the genetic control of glucosinolate production is becoming clear through studies of Arabidopsis and Brassica crops. It is now established that a small number of loci, each with well-defined effects, controls the type, and to a large extent the concentration, of glucosinolates. Secondly, it is reasonably straightforward to identify glucosinolates of wild plants using high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, and from the profiles infer genotypes at loci controlling biosynthesis. Thirdly, there is a large literature on the effects of purified glucosinolates on the behaviour and physiology of crop pests. These pests are also found in natural populations of crucifers. Finally, isogenic lines of Brassica species that differ only in their glucosinolate profiles are becoming available, enabling the effects of individual glucosinolates to be tested in planta. These isogenic lines mimic variation found in natural populations and remove the confounding effects of genetic variation at other loci. The disadvantage is that the variation is expressed in a crop genetic background.

Over the last 50 years, ecological geneticists have learned much about how demographic processes determine patterns of intraspecific genetic variation. There has been comparatively very little work on to what extent intraspecific genetic variation controls demography. This is of great current importance because our inability to predict the environmental effects of genetically modified crops and their hybrids with wild relatives reflects our ignorance about how genetic variation drives the demography of plants and species that feed on them (e.g. Keeler, 1989). Glucosinolates offer a system in which to study the demographic consequences for wild plants and their herbivores of genetic variation for agriculturally important traits.

Levin & Udovic (1977) developed a useful conceptual framework (Fig. 1) that describes the processes that link genetic variation and numerical abundance of two noninterbreeding but interacting populations (e.g. a plant species and a herbivore species feeding on it). Antonovics (1992) points out that while the Levin and Udovic model is too simplistic, it also very easy to over-parameterize if one attempts to make it more realistic. However, he stresses that it is important to attempt analyses based on the model if one wishes to predict interactions between population dynamics of species abundance, population size and gene frequency (i.e. ecological genetics). Antonovics and colleagues have developed the approach of Levins and Udovic to analyse the interaction between the anther smut fungus, Ustilago violacea, and one of its host speices, Silene alba (e.g. Alexander et al., 1996).

Basic interactions between densities and allele frequencies for a plant-herbivore interaction (adapted from Levin & Udovic, 1977). Arrow 1: intraspecific density-dependent regulation of population growth rates. Arrow 2: interspecific density-dependent regulation of population growth rates. Arrow 3: intraspecific frequency-dependent (density-independent) selection. Arrow 4: density-independent co-selection. Arrow 5: intraspecific genetic feedback (intraspecific density-dependent selection and intraspecific frequency-dependent regulation of population growth rate. Arrow 6: interspecific genetic feedback (interspecific density-dependent selection and reciprocal interspecific frequency-dependent regulation of population growth rates).

The purpose of this paper is not to discuss the Levins–Udovic framework in detail, but instead to describe data on the distribution and consequences of genetic variation for glucosinolate profiles within the Levins–Udovic framework. In particular, we will discuss the interactions between allelic variation at loci controlling glucosinolate biosynthesis and plant and herbivore dynamics (arrows 5a, 5b, 6a and 6b in Fig. 1). We will also consider briefly the regulation of plant density by herbivores that interact with glucosinolates (2b), interactions between genetic variation in the herbivores and plant genotype (4a and 4b) and frequency-dependent selection on glucosinolate genotype (3a). Outside the scope of this review are intraspecific density-dependent regulation of plant and herbivore populations (1a and 1b, respectively); the regulation of herbivore density by plant density (2a); interactions between herbivore genetic variation and plant and herbivore dynamics (6c, 6d, 5c and 5d) and frequency dependent selection in herbivore populations (3b).

Genetic variation for glucosinolates in natural populations

All glucosinolates have a common thioglucose group but vary in their side-chain structure, which is derived from an amino acid: aliphatic glucosinolates are derived from methionine, indolyl glucosinolates from tryptophan and aromatic glucosinolates from phenylalanine. The genetics of biosynthesis and modification of side-chain structure differ among the glucosinolate types. Little is known about the genetic control of biosynthesis of aromatic and indolyl glucosinolates. Indolyl glucosinolates are influenced strongly by environmental factors but some heritable variation for concentration has been found and is likely to be the result of 2–3 genes in Brassica napus (Rucker & Robbelson, 1994). In contrast, the aliphatic glucosinolates are under strong genetic control and the genetics of their side-chain structure and concentration are well characterized.

Aliphatic glucosinolate side-chain structure is determined by elongation of the initial side-chain and subsequent modifications, such as oxidation, desaturation and hydroxylation. Variation in the type of modification is often controlled by allelic variation at a single locus (see Mithen, 2001 for a review). For example, single loci control elongation of the side-chain (gsl-elong), conversion of methylthioalkyl side-chains to methylsulphinylalkyl side-chains (gsl-oxid) and then to alkenyl side-chains (gsl-alk) and hydroxylation of alkenyl side-chains (gsl-oh) (see Fig. 2 for synthesis of glucosinolates in B. oleracea). The situation in Arabidopsis differs from B. oleracea in that functional alleles at an additional locus gsl-ohp convert methylsulphinylpropyl glucosinolate to hydroxypropyl glucosinolate. It is likely that gsl-alk and gsl-ohp are the products of tandem duplication and divergence of an ancestral 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase gene (Kliebenstein et al., 2001). An RFLP probe to gsl-ohp cosegregates with gsl-alk in B. oleracea (Hall et al., 2001) even though this species does not produce hydroxypropyl glucosinolate.

Concentrations of the aliphatic glucosinolates are also under strong genetic control with a high heritability (h2=0.87 in B. napus, Rucker & Robbelen, 1994). Between two and five independent genes in B. napus appear to control 71% of the variation in aliphatic glucosinolate concentration, with gsl-elong and gsl-alk mapping as QTLs for this trait (Toroser et al., 1995). gsl-elong also maps as a QTL for glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Campos de Quiros et al., 2000).

A further level of genetic control acts on the breakdown of the glucosinolates. The initial reaction is catalysed by the enzyme myrosinase (Fig. 2). Multiple forms of myrosinase are encoded by a gene family consisting of about 10 genes in B. napus and three genes in A. thaliana (Rask et al., 2000). Heritable increases in myrosinase production have been produced by artificial selection in B. rapa (Siemens & Mitchell-Olds, 1998). A number of products can result from glucosinolate decomposition (Fig. 2) depending on reaction conditions. The reaction mechanisms of some degradation pathways are not clear, but it is known that epithiospecifier protein and ferrous ions catalyse the production of cyanoepithioalkanes and it seems likely that presence/absence of epithiospecifier protein is a key determinant of the ratio of breakdown products produced (Bones & Rossiter, 1996; Foo et al., 2000).

Much is known about interspecific variation in glucosinolate profiles: over 120 glucosinolates have been identified from about 300 plant species (see Daxenbichler et al., 1991 and Fahey et al., 2000 for comprehensive reviews). Information about intraspecific variation is much scarcer. Louda & Rodman (1983) studied glucosinolates in Cardamine cordifolia plants growing along a 7-km transect and at two nearby sites. They split the glucosinolates into two groups, those that broke down to isothiocyanates (IYG) and those that broke down to oxazoladinethiones (OYG). However, they were not able to quantify every individual glucosinolate. They found differences in both the proportion of plants producing OYGs and in the concentration of IYGs at different elevations. Rodman (1980) investigated 11 populations of C. edentula and found relatively uniform glucosinolate profiles, in terms of types and concentrations, within populations of two subspecies. Some sympatric populations of the Cardamine species produce hybrids with intermediate concentrations with glucosinolate types from both parents.

Mithen & Campos (1996) found polymorphism at gsl-elong and gsl-ohp among landraces of A. thaliana in Europe. Ecotypes from central and eastern Europe had only propyl glucosinolates (gsl-elong−), whereas ecotypes from western Europe mostly had both propyl and butly glucosinolates (gsl-elong+). Plants with hydroxy propyl glucosinolate (gsl-ohp+) were most common in Germany & Austria. Mauricio (1998) found genetic variation for total glucosinolate concentration in four discrete neighbouring natural populations of A. thaliana in North Carolina.

Moyes et al. (2000) quantified individual glucosinolates in differing habitats within four wild populations of B. oleracea. They found variation within and among populations in the concentrations of aliphatic glucosinolates produced and differences in the frequency of plants with particular aliphatic glucosinolates among populations. Variation in glucosinolate concentration found in wild populations of B. oleracea was maintained in greenhouse grown plants (Mithen et al., 1995). This result, taken with the data on the high heritability in B. napus (see above), strongly suggests that heritability for aliphatic glucosinolate variation is high in wild populations of B. oleracea. Other species show very little variation; for example B. nigra contains only 2-propenyl glucosinolate (Mithen et al., 1995).

To summarize, genetic studies of the aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis have given a lot of information on control of side-chain structure and concentration. This work is still in progress and more information will soon be available. Less work has been done on the frequency of these genes in wild populations, but studies have shown that variation exists within and among plant populations.

Aliphatic glucosinolates and herbivore behaviour

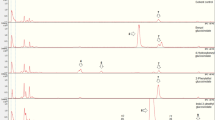

Several studies have shown a relationship between variation in the presence and/or concentration of aliphatic glucosinolates (or their degradation products) and the behaviour of herbivores. Table 1 summarizes studies of individual glucosinolates and Table 2 summarizes studies where herbivores were able to choose between glucosinolates, plants or populations.

Both glucosinolate concentration and profile seem to have effects. Generalist herbivores, such as molluscs, tend to prefer to feed on plants with lower concentrations of glucosinolates. On the other hand, herbivores that specialize on crucifers tend to prefer to feed and lay eggs on plants with higher concentrations of glucosinolates. Parasitoids of specialist herbivores are also attracted by higher glucosinolate concentrations.

Herbivores can show differential response to glucosinolates with different side-chain structures. For example, the oviposition response of Pieris butterflies to 2-propenyl glucosinolate is much stronger than that to glucosinolates with longer side-chains (Huang & Renwick, 1994). The development of near-isogenic lines allows the effects of individual glucosinolates to be studied in planta. Bradburne & Mithen (2000) showed that Diaeretiella rapae, a parasitoid of the cabbage aphid, was attracted to lines of B. oleracea with the ‘4C’ rather than the ′3C’allele at gsl-elong. A major difference between the lines was the greater production of 3-butenyl isothiocyanate by the plants with gsl-elong4C.

The role of glucosinolate polymorphism in wild plants

Wild populations are variable for genes that control glucosinolate side-chain structure and concentration and many studies have shown that herbivores detect and can respond differentially to glucosinolate variation (see above). However few studies have tested whether intraspecific variation in glucosinolate profile affects the amount of herbivory plants suffer, and whether any differences in herbivory result in differences in fitness.

There is evidence that differential levels of herbivory can result where herbivores are presented with a choice in field trials. Stowe (1998) found that artificially selected variation in glucosinolate concentration of Brassica rapa resulted in differential herbivory by Pieris rapae and Trichoplusia ni larvae. Both the specialist (Pieris) and the generalist herbivore preferred low glucosinolate concentrations. Giamoustaris & Mithen (1995) found that glucosinolate variation in B. napus affected amounts of herbivory caused by specialist herbivores (Psylloides chrysocephala and Pieris rapae) and generalist herbivores (pigeons and slugs). Compared with the low glucosinolate lines, the lines with high glucosinolates were damaged more by the specialists and less by the generalists. Differences in 3-butenyl glucosinolate concentration were correlated with the variation in behaviour of Psylloides.

Many of the relationships between behaviour and glucosinolates detected in controlled studies have not been found in natural populations. Moyes et al. (2000) found differences in glucosinolate profiles among wild populations of B. oleracea on the Dorset coast (see above). The range of variation was broadly similar to that shown to have an effect in field trials with oilseed rape. However, no relationship was found between individual plant glucosinolate profile and the amount of herbivore damage suffered by adult plants, despite the presence of several generalist and specialist herbivores of Brassica.

There were, however, two exceptions. In one out of four populations, plants infested with the micromoth Selania leplastriana had significantly higher concentrations of 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl glucosinolate. In the same population, infested plants also had significantly higher concentrations of 3-indolymethyl glucosinolate. However, unlike aliphatic glucosinolates, the indolyls are greatly induced by herbivory and the high amount could be the result, rather than the cause, of infestation.

The second association between glucosinolate profile and herbivory was found at the population scale. Moyes & Raybould (2001) showed that among populations of B. oleracea there was a very high correlation between the average concentration of 3-butenyl glucosinolate and the proportion of pods infested with larvae of the cabbage seed weevil (Ceutorhynchus assimilis) and the number of seed eaten by the weevil. Within populations there was no relationship between the 3-butenyl concentration of plants and weevil infestation. The population effect was not detected for any other glucosinolate, nor was it related to plant density or attack by parasitoids of the weevil (Moyes & Raybould, 2001). Moyes & Raybould (2001) suggest that seed weevils are attracted into patches by high concentrations of 3-butenyl isothiocyanate. The correlation between seed weevils and 3-butenyl glucosinolate is evidence that allelic variation for glucosinolate side-chain structure can influence herbivore behaviour in natural populations, but that effects may not be seen at the scale of individual plants.

If polymorphism in glucosinolate profile is associated with different amounts of herbivory between plants, a number of effects may result. First, it is possible that herbivory will have an impact on the host plant populations in terms of glucosinolate allele frequencies and/or plant population dynamics. A second possibility is that glucosinolate allele frequencies in the host plant population will affect herbivore species in terms of selection for resistance/tolerance to glucosinolates and/or herbivore population dynamics. Thirdly, the differential levels of herbivory involving a particular herbivore and plant species may have no significant impact on either the plant or the herbivore populations.

Impacts on plant populations

In order for differential levels of herbivory to act as a selection pressure on glucosinolate alleles, it must have an effect on plant fitness. Having previously found that feeding by two adapted herbivores in natural communities of Cardamine cordifolia was related to low glucosinolate concentrations (Louda & Rodman, 1983, Louda (1984) found that removal of these herbivores improved plant performance in terms of stature, leaf area and fruit production. Mauricio & Rausher (1997) showed that by excluding all insects and fungal pathogens from populations of A. thaliana they could release these plants from selection favouring high total glucosinolate concentration.

Damage by seed weevils significantly reduces seed output of wild B. oleracea plants (Moyes & Raybould, 1998) and plants in populations with high average concentration of 3-butenyl glucosinolate are attacked preferentially (see above). If the reduction of seed output is sufficient to reduce plant fitness, complex patterns of selection could act on loci that directly determine the concentration of 3-butenyl glucosinolate (i.e. gsl-elong and gsl-oh). Frequency dependent selection may occur because the behaviour of the seed weevil is determined by the average phenotype of a patch of plants. There are also possible trade-offs between resistance to slugs and attraction of seed weevils. Giamoustaris & Mithen (1995) studied oilseed rape lines with similar concentrations of total aliphatic glucosinolates. A line with a low ratio of 3-butenyl glucosinolate: 2-propenyl glucosinolate + 2-hydroxy-3-butenyl glucosinolate was more susceptible to slugs than a line with a higher ratio of 3-butenyl glucosinolate to the other glucosinolates. Taken together, these data show that natural selection for altered glucosinolate phenotypes (concentration and type) is possible.

In contrast, there have been no studies that have directly considered the link between glucosinolate alleles, herbivory and plant population dynamics. High insect herbivore populations in sunny, as opposed to shady habitats, appeared to control the distribution of C. cordifolia (Collinge & Louda, 1988; Louda & Rodman, 1996). This particular herbivore is not the same as those previously found to be influenced by the glucosinolates in C. cordifolia (Louda & Rodman, 1983), although an environmentally controlled glucosinolate difference may play a role in this effect. Duggan (1985) found a small impact on C. pratensis populations resulting from a large impact of herbivory by Anthocharis cardamines on seed mortality. Raybould et al. (1999) showed that exclusion of slugs and/or insect herbivores has a significant impact on the dynamics of artificially established feral populations of B. napus. These studies indicate that herbivory of glucosinolate-containing plants can have an impact on plant population dynamics, but whether variation in glucosinolate phenotypes alters herbivory to a degree that will have an effect is still unknown.

Impacts on herbivore populations

Specialist herbivores of the Brassicaceae not only tolerate glucosinolates, they also utilize these compounds in host recognition (see Tables 1 and 2. This ability is often quoted as an example of genetic changes in herbivore populations brought about by glucosinolate alleles in host plants. In order for herbivores to evolve in response to glucosinolates, populations must contain genetic variation for their ability to tolerate/utilize these compounds. For example, De Jong & Nielsen, 1999) found genetic variation in flea beetles (Phyllotreta nemorum) for response to resistant and susceptible genotypes of the crucifer Barbarea vulgaris (yellow rocket). They also discovered a cost to resistance in some beetle populations (De Jong & Nielsen, 2000a; De Jong & Nielsen, 2000b). However, it is not known whether plant resistance/susceptibility is mediated through glucosinolates.

Intraspecific variation in plant phenotype can mediate herbivore dynamics through host recognition or host quality (e.g. Lawton & Strong, 1981; Morris & Dwyer, 1997). Although no studies have yet demonstrated such an effect related to intraspecific variation in glucosinolates, there are observations that suggest such effects are possible. Wild cabbage plants in populations with low average amounts of 3-butenyl glucosinolate support fewer larvae of Ceutorhynchus assimilis than nearby populations with higher amounts of that compound (Moyes & Raybould, 2001). Cole (1997) found correlations between the intrinsic rate of increase of Brevicoryne brassicae and the concentration of aliphatic glucosinolates within and among Brassica species.

No impact

Even if variation in glucosinolate profiles does affect amounts of herbivory, there may be no impact on either plant or herbivore populations. Many of the herbivores that interact with glucosinolates are invertebrates. Rees & Long (1992) found that although mollusc herbivory caused a 30% decrease in fecundity of Sinapis arvensis, this was unlikely to be important in determining the distribution of that species. Furthermore, insect herbivores had even less impact on fecundity than the molluscs (Rees & Brown, 1992). For this ephemeral species, germination control appears to be an important factor in its population dynamics. Most studies of the impact of invertebrate herbivores on plant populations have reduced the damage caused by herbivores by excluding them completely (e.g. Crawley, 1989). However, the impact of altered glucosinolate allele frequencies on the intensity of herbivory is likely to be much less than complete herbivore exclusion, thus reducing potential impacts on plant population dynamics.

Even specialist herbivores of glucosinolate-containing plants can feed on more than one host species and the broader their host range the more likely it is that they will have ample alternative food sources. This may act to prevent an impact on herbivore populations. In addition, herbivore preferences for particular glucosinolate profiles may be determined by factors such as maternal environment rather than genetic control of behaviour (e.g. Renwick & Lopez, 1999).

Conclusion

In this review we have shown that polymorphism at loci controlling glucosinolate biosynthesis is readily detectable in populations of wild crucifers and in at least some cases is associated with variation in herbivore behaviour. We suggest therefore that variation in aliphatic glucosinolate phenotypes in Brassica and related species is an attractive system for investigating the effects of intraspecific genetic variation on plant–herbivore interactions. The system has many similarities with cyanogenesis, another trait that is controlled by allelic variation at major genes, and which appears to play a role in defence against herbivory (see Jones, 1998; for a review). Compared with cyanogenesis, we are probably in a better position to study the effects of intraspecific polymorphism for glucosinolates on herbivore dynamics because of the wealth of information from controlled studies (Tables 1 and 2. The major weakness of the glucosinolate system as it stands is the lack of information about interactions between genetic variation in the herbivores and plant genotype (arrows 4a and 4b in Fig. 1) and interactions between herbivore genetic variation and plant and herbivore dynamics (arrows 6c, 6d, 5c and 5d). The work of de Jong and colleagues on genetic variation in flea beetles feeding on Barbarea vulgaris shows the potential for studying these aspects of the glucosinolate–herbivore interaction.

References

Alexander, H. M., Thrall, P. H., Antonovics, J., Jaroz, A. M. and Oudemans, P. V. (1996). Population dynamics and genetics of plant disease: a case study of anther-smut disease. Ecology, 77: 990–996.

Antonovics, J. (1992). Towards community genetics. In: Fritz, R. S and Simms, E. L., (eds) Plant Resistance to Herbivores and Pathogens, pp. 426–449. University of Chicago Press.

Bones, A. M. and Rossiter, J. (1996). The myrosinase-glucosinolate system, its organisation and biochemistry. Physiol Plant, 97: 194–208.

Bradburne, R. P. and Mithen, R. (2000). Glucosinolate genetics and the attraction of the aphid parasitoid Diaeretiella rapae to Brassica. Proc R Soc B, 267: 89–95.

Campos de Quiros, H. C., Magrath, R., McCallum, D., Kromann, J., Schnabelrauch, D. and Mitchell-Olds, T. et al. (2000). Alpha-keto acid elongation and glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Theor Appl Genet, 101: 429–437.

Cole, R. A. (1997). The relative importance of glucosinolates and amino acids to the development of two aphid pests Brevicoryne brassicae and Myzus persicae on wild and cultivated brassica species. Entomologia Exp Appl, 85: 121–133.

Collinge, S. K. and Louda, S. M. (1988). Herbivory by leaf miners in response to experimental shading of a native crucifer. Oecologia, 75: 559–556.

Crawley, M. J. (1989). Insect herbivores and plant population dynamics. Ann Rev Ent, 34: 531–564.

Daxenbichler, M. E., Spencer, G. F., Carlson, D. G., Rose, G. B., Brinker, A. M. and Powell, R. G. (1991). Glucosinolate composition of seeds from 297 species of wild plants. Phytochemistry, 30: 2623–2638.

de Jong, P. W. and Nielsen, J. K. (1999). Polymorphism in a flea beetle for the ability to use an atypical host. Proc R Soc B, 266: 103–111.

de Jong, P. W. and Nielsen, J. K. (2000a). Reduction in fitness of flea beetles which are homozygous for an autosomal gene conferring resistance to defences in Barbarea vulgaris. Heredity, 84: 20–28.

de Jong, P. W. and Nielsen, J. K. (2000b). Genetics of resistance against defences of the host plant Barbarea vulgaris in a Danish flea beetle population. Proc R Soc B, 267: 1663–1670.

Duggan, A. E. (1985). Pre-dispersal seed predation by Anthocharis cardmines (Pieridae) in the population dynamics of the perennial Cardamine pratensis. Oikos, 44: 99–106.

Fahey, J. W., Zalcman, A. T. and Talalay, P. (2000). The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry, 56: 5–51.

Foo, H. L., Gronning, L. M., Goodenough, L., Bones, A. M., Danielson, B. and Whiting, D. A. et al. (2000). Purification and characterisation of epithiospecifier protein from Brassica napus: enzymatic intramolecular sulphur addition within alkenyl thiohydroximates derived from alkenyl glucosinolate hydrolysis. FEBS Lett, 468: 243–246.

Friedt, W. and Luhs, W. (1998). Recent developments and perspectives of industrial rapeseed breeding. Fett/Lipid, 100: 219–226.

Giamoustaris, A. and Mithen, R. (1995). The effect of modifying the glucosinolate content of oilseed rape (Brassica napus ssp. oleifera) on its interaction with specialist and generalist pests. Ann Appl Biol, 126: 347–363.

Hall, C., McCallum, D., Prescott, A. and Mithen, R. (2001). Biochemical genetics of glucosinolate modification in Arabidopsis and Brassica. Theor Appl Genet, 102: 369–374.

Huang, X. P. and Renwick, J. A. A. (1994). Relative activities of glucosinolates as oviposition stimulants fpr Pieris rapae and P. napi oleracea. J Chem Ecol, 20: 1025–1037.

Jones, D. A. (1998). Why are so many food plants cyanogenic? Phytochemistry, 47: 155–162.

Keeler, K. H. (1989). Can genetically engineered crops become weeds? Bio/Technology, 7: 1134–1139.

Kliebenstein, D. J., Lambrix, V. M., Reichelt, M., Gershenzon, J. and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2001). Gene duplication in the diversification of secondary metabolism: tandem 2-oxaloglutarate-dependent dioxygenases control glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Pl Cell, 13: 681–693.

Lawton, J. H. and Strong, D. R. (1981). Community patterns and competition in foliovorous insects. Am Nat, 118: 317–338.

Levin, S. A. and Udovics, J. D. (1977). A mathematical model of coevolving populations. Am Nat, 111: 657–675.

Louda, S. M. (1984). Herbivore effect on stature, fruiting and leaf dynamics of a native crucifer. Ecology, 65: 1379–1386.

Louda, S. M. and Rodman, J. E. (1983). Ecological patterns in the glucosinolare content of a native mustard, Cardamine cordifolia, in the Rocky Mountains. J Chem Ecol, 9: 397–423.

Louda, S. M. and Rodman, J. E. (1996). Insect herbivory as a major factor in the shade distribution of a native crucifer (Cardamine cordifolia A. Gray, bittercress). J Ecol, 86: 229–237.

Mauricio, R. (1998). Costs of resistance to natural enemies in field populations of the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Am Nat, 151: 20–28.

Mauricio, R. and Rausher, M. D. (1997). Experimental manipulation of putative selective agents provides evidence for the role of natural enemies in the evolution of plant defence. Evolution, 51: 1435–1444.

Mithen, R. (2001). Glucosinolates and their degradation products. Adv Bot Res, in press.

Mithen, R. and Campos, H. (1996). Genetic variation of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana and prospects for map based gene cloning. Entomol Exp Appl, 80: 202–205.

Mithen, R., Raybould, A. F. and Giamoustaris, A. (1995). Divergent selection for secondary metabolites between wild populations of Brassica oleracea and its implications for plant–herbivore interactions. Heredity, 75: 472–484.

Morris, W. F. and Dwyer, G. (1997). Population consequences of constitutive and inducible plant resistance: Herbivore spatial spread. Am Nat, 149: 1071–1090.

Moyes, C. L. and Raybould, A. F. (1998). Herbivory by the cabbage seed weevil (Ceutorhynchus assimilis) in natural populations of Brassica oleracea subsp. oleracea. Acta Hort, 459: 315–322.

Moyes, C. L. and Raybould, A. F. (2001). The role of spatial scale and intraspecific variation in secondary chemistry in host plant location by Ceutorhynchus assimilis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Proc R Soc B, 268: 1567–1753.

Moyes, C. L., Collin, H. A., Britton, G. and Raybould, A. F. (2000). Glucosinolates and differential herbivory in wild populations of Brassica oleracea. J Chem Ecol, 26: 2625–2641.

Rask, L., Andreasson, E., Ekbom, B., Eriksson, S., Pontoppidan, B. and Meijer, J. (2000). Myrosinase: gene family evolution and herbivore defence in Brassicaceae. Plant Mol Biol, 42: 93–113.

Raybould, A. F., Moyes, C. L., Maskell, L. C., Mogg, R. J., Warman, E. A. and Wardlaw, J. C. et al. (1999). Predicting the ecological impacts of transgenes for insect and virus resistance in natural and feral populations of Brassica species. In: Ammann, K., Jacot, Y., Simonsen, V. and Kjellsson, G. (eds) Methods of Risk Assessment of Transgenic Plants III. Ecological Risks and Prospects of Transgenic Plants, pp. 3–15. Bïrkhäuser, Basel.

Rees, M. and Brown, V. K. (1992). Interactions between invertebrate herbivores and plant competition. J Ecol, 80: 353–360.

Rees, M. and Long, M. J. (1992). Germination biology and the ecology of annual plants. Am Nat, 139: 484–508.

Renwick, J. A. A. and Lopez, K. (1999). Experience-based food consumption by larvae of Pieris rapae: addiction to glucosinolates? Entomologia Exp Appl, 91: 51–58.

Rodman, J. E. (1980). Population variation and hybridization in sea-rockets (Cakile: Cruciferae): seed glucosinolate characters. Am J Bot, 67: 1145–1159.

Rucker, B. and Robbelen, G. (1994). Inheritance of total and individual glucosinolate contents in seeds of oileed rape (Brassica napus L.). Pl Breed, 113: 206–216.

Siemens, D. H. and Mitchell-Olds, T. (1998). Evolution of pest-induced defenses in Brassica plants: tests of theory. Ecology, 79: 632–646.

Stowe, K. A. (1998). Realized defence of artificially selected lines on Brassica rapa: effects of quantitative genetic variation in foliar glucosinolate concentration. Environ Entomol, 27: 1166–1174.

Toroser, D., Thormann, C. E., Osborn, T. C. and Mithen, R. (1995). RFLP mapping of quantitative trait loci controlling seed aliphatic glucosinolate content in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Theor Appl Genet, 91: 802–808.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raybould, A., Moyes, C. The ecological genetics of aliphatic glucosinolates. Heredity 87, 383–391 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00954.x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00954.x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

AAL-toxin induced stress in Arabidopsis thaliana is alleviated through GSH-mediated salicylic acid and ethylene pathways

Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) (2020)

-

Variation in Below-to Aboveground Systemic Induction of Glucosinolates Mediates Plant Fitness Consequences under Herbivore Attack

Journal of Chemical Ecology (2020)

-

Host plant iridoid glycosides mediate herbivore interactions with natural enemies

Oecologia (2018)

-

Complex effects of parasitoids on pharmacophagy and diet choice of a polyphagous caterpillar

Oecologia (2011)

-

Soil microbial communities alter allelopathic competition between Alliaria petiolata and a native species

Biological Invasions (2010)