Abstract

Aortic complicated lesions (ACLs) should be associated with cerebral infarction. Our aim was to develop a simple clinical scale (ACL scale) to predict the presence of ACL. Consecutive stroke patients undergoing transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) examination were prospectively enrolled. We defined ACL as the presence of >4 mm wall thickness, ulceration or mobile plaque in aortic arch. We also examined carotid intima–media thickness (IMT), ankle-brachial index (ABI) and brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity (baPWV). We compared the clinical characteristics of patients with ACL (ACL group) and without ACL (non-ACL group), and devised a new ACL scale to predict the presence of ACL. In all, 165 patients (male 108, age 66.9 years) were enrolled and of these, 38% had ACL. The patients of the ACL group were older than those of the non-ACL group (73.0±10.2 vs. 63.1±13.6 years, P=0.001). Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was more frequent in the ACL group (18 vs. 4%, P=0.004). IMT was thicker in ACL group than in the non-ACL group (1.29±0.74 vs. 1.11±0.79 mm, P=0.002), and baPWV was higher in the ACL group (2164.2±643.2 vs. 1833.7±492.9 cm s−1, P=0.001). We used three variables for determining the ACL scale score; (1) age >70, (2) presence of PAD and (3) smoking. The frequencies of ACL associated with ACL scale scores were as follows: 6% of patients with ACL scale score 0, 40% with score 1, 58% with score 2 and 100% with score 3. The ACL scale can predict the presence of aortic complicated lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aortic complicated lesions (ACLs), which are generally evaluated using transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), appear to contribute to the occurrence of embolic stroke. Several investigations1, 2, 3, 4, 5 have indicated that ACLs should be estimated in patients with stroke of unknown etiology. In the general population aged 45 years or older, 25.6% of the subjects had atherosclerosis in the aortic arch.6 It has been reported that factors associated with ACL include age,1, 7 cigarette smoking,1, 8, 9 hypertension,10 diabetes mellitus11 and coronary artery disease.12, 13

Less invasive methods have recently been developed to examine systemic atherosclerosis. Brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity (baPWV) can be used to measure aortic stiffness,14, 15 and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) can be diagnosed using the ankle-brachial index (ABI).16 Carotid intima–media thickness (IMT), as shown by duplex carotid ultrasonography, has been one of the most commonly used measurements in the last decade.17, 18 As regards the relationship between ACL and atherosclerotic markers evaluated by these devices, aortic PWV and carotid IMT were individually reported to be correlated with the presence of ACL.15

Our aim was to examine the associations between generalized atherosclerotic markers including carotid IMT, PWV, ABI and ACL, in stroke patients, and to devise a simple scale to predict the presence of ACL.

Methods

Study population and vascular risk factors

From October 2006 to June 2007, we prospectively enrolled consecutive stroke patients who were examined for the presence of ACL using TEE. We included patients with old and acute cerebral infarction. We assessed the following vascular risk factors: (1) hypertension, defined as a history of the use of antihypertensive agents, a systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg; (2) diabetes mellitus, defined as the use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin, a fasting blood glucose level >126 mg dl−1 or casual blood glucose level ⩾200 mg dl−1; (3) hyperlipidemia, defined as the use of antihyperlipidemic agents or a serum cholesterol level >220 mg dl−1; (4) current smoking status; (5) history of alcohol consumption was obtained; (6) coronary artery disease was defined as a history of angina pectoris or myocardial infarction; (7) PAD, defined as a history of the treatment of PAD with intermittent claudication and (8) stroke subtype, determined according to the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria.19

Clinical protocol

We carried out routine blood biochemistry examinations, blood count, ECG and radiography of the chest, and measured the IMT of the common carotid artery on admission. TEE was performed to detect sources of embolus, thrombus in the left-atrial appendage and ACL. We measured ABI and baPWV within 2 days before or after TEE.

Ultrasound TEE

TEE was performed using the HDI 5000 (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA, USA) with a 4–7 MHz wideband multiplane probe. All the patients were awake and were given no premedication. We sprayed Lidocaine (Astra Zeneca, Osaka, Japan) into the pharynx. The probe was advanced to the distal esophagus and withdrawn slowly to a location about 25 cm from the incisors. We observed the aortic arch in both transverse and sagittal views. Plaque thickness was defined as intima–media thickness (IMT) of the walls at the aortic arch in transverse view. We evaluated maximum IMT at the arch. We defined aortic complicated lesions (ACL) as the presence of >4 mm thickness of maximum IMT, ulceration mobile plaque. The examinations were performed by experienced sonographers (YT, YO and NM) and recorded on a super VHS videotape. TEE findings were reviewed by experienced sonographers (YT and NM), who were blinded to the clinical data. We divided all patients into two groups: those with ACL (ACL group) and those without ACL (non-ACL group).

Carotid duplex ultrasonography studies were performed using the HDI 5000 (Philips Medical Systems) with a 7–12 MHz linear-array probe. We evaluated atherosclerosis of the common carotid arteries (CCAs), the carotid bifurcations and the proximal internal carotid artery (ICA). When an optimal longitudinal image of the CCA was obtained, it was frozen and stored on the VHS videotape. We assessed the maximum IMT, as reported earlier.18 Maximum IMT of the CCA was defined as the single thickest region of the near and far walls of the right or left CCA.

PWV, ABI

ABI and baPWV were measured using a volume-plethysmographic apparatus (FORM PWV/ABI; Omlon, Colin, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan) within 2 days before or after TEE. The patients were examined in the supine position, with electrocardiographic electrodes placed on both wrists, a microphone for detecting heart sounds placed on the left edge of the sternum, and cuffs wrapped on both the brachia and ankles. The method used has been described in detail elsewhere.14, 20 After ABI and baPWV examinations had been performed on both the right and left sides, we chose the lower ABI and higher baPWV for use in statistical analysis. We defined PAD for this purpose as the lowest ABI below 0.9.16

Analysis

Values are presented as mean and s.d. for continuous variables, and as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. As variables identified from univariate analysis at P<0.2 were considered explanatory variables, we also carried out multivariate logistic-regression analysis to determine factors independently associated with the presence of ACL. The cut-off values for age, PWV, IMT, creatinine and fibrinogen were determined by receiver operated characateristic curves. SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis, with P-values <0.05 considered significant.

Results

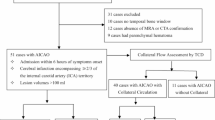

From October 2006 to June 2007, 380 stroke patients visited our hospital. There were 71 patients (19%) with cerebral hemorrhage, 261 (69%) with cerebral infarction and 48 (12%) with transient ischemic attack (TIA). Of them, we performed TEE on 200 (65%) patients. We excluded 35 patients for the following reasons: (1) 10 patients owing to agitation due to difficulty in swallowing, (2) eight patients owing to atrial fibrillation with variability in R-R interval too large for examination of PWV, (3) five patients owing to brachial shunt for dialysis, (4) four patients owing to their critical condition, (5) four patients because of casts on their arm or leg due to bone fracture, (6) two patients owing to severe PAD and ankle blood pressure too low for examination of PWV and (7) two patients owing to lack of informed consent. We thus enrolled 165 patients (male 65%, age 66.9±13.2 years) in this study. By stroke subtype, 12 of 72 (17%) patients with unknown etiology probably had aortogenic stroke. To prevent recurrence of stroke, antiplatelet agents were given to 10 patients whereas anticoagulation was carried out for only one patient with mobile plaque (data not shown).

Baseline characteristics

ACL was observed in 63 of 165 (38%) patients on TEE examination. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 165 patients. Patients with ACL were older than those without it (73.0±10.2 vs. 63.1±13.6 years, P=0.001). Smoking was more frequent in the ACL group than in the non-ACL group (59 vs. 42%, P=0.046), and the Brinkman index of the ACL group patients was higher than that of non-ACL group patients (532±622 vs. 344±511, P=0.026). There were no differences in other baseline characteristics, including vascular risk factors and past history between the ACL and non-ACL groups.

Markers of atherosclerosis

In the ACL group, IMT was greater than that in the non-ACL group (1.29±0.74 vs. 1.11±0.79 mm, P=0.002), and PWV was higher than in the non-ACL group (2164.2±643.2 vs. 1833.7±492.9 cm s−1, P=0.001). There was no significant difference in ABI between the two groups (1.08±0.12 vs. 1.11±0.09, P=0.087), but PAD (ABI <0.9) was more frequent in the ACL group than that in the non-ACL group (18 vs. 4%, P=0.004). Patients whose CCA IMT was ⩾1.0 mm were more frequent in the ACL than in the non-ACL group (46 vs. 26%, P=0.004).

Laboratory data

The results of hematological examination of the 165 patients are shown in Table 2. Serum creatinine in the ACL group was higher than that in the non-ACL group (1.2±2.2 vs. 0.8±0.5 mg dl−1, P=0.031), and fibrinogen was higher in the ACL group than in the non-ACL group (307.9±75.6 vs. 286.7±87.2 mg dl−1, P=0.035). However, there were no differences in other laboratory parameters between the two groups.

ACL scale score

The factors independently associated with the presence of ACL were age (odds ratio (OR): 4.5; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.9–10.6; P=0.001), smoking (OR: 3.5; 95% CI, 1.6–7.9, P=0.003) and PAD (ABI<0.9) (OR: 6.0; 95% CI, 1.4–26.5, P=0.017) (Table 3).

We chose these three variables to use for the ACL scale score. The scale included (1) over 70 years of age, (2) the presence of smoking and (3) the presence of PAD. If a patient was positive for a variable, we assigned 1 point, with a possible total of 3 points. We examined whether ACL scale score predicted the presence of ACL.

The relationship between ACL scale score and frequency of ACL is shown in Figure 1. Frequencies of ACL for each scale score were as follows: 6% of patients with ACL scale score 0, 40% with score 1, 58% with score 2 and 100% with score 3. On the other hand, 94% of the patients with an ACL scale score of 0 did not have ACL. As ACL scale score became higher, ACL was more frequent in the present series.

Discussion

In this study, univariate analysis showed that ACL was associated with age, smoking habit, carotid IMT, the presence of PAD and high PWV. We also found that ACL scale score, which includes age, smoking and the presence of PAD, can predict the presence of aortic complicated lesions in stroke patients.

In our study, carotid IMT was greater in the ACL group than in the non-ACL group. This finding is consistent with earlier reports that carotid atherosclerosis is associated with ACL in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease.12, 15 Increased carotid IMT is generally recognized as an early marker of atherosclerosis.17, 21, 22 We consider carotid IMT a good rough marker for use in evaluating the presence of ACL.

The baPWV value of patients with ACL (>4.0 mm) was higher than that of those without it. This result accords with the finding of the Rotterdam Study that direct aortic PWV is strongly associated with the severity of plaque in the aorta.23, 24, 25 A strong relationship between aortic PWV and baPWV has been reported.14 Non-invasive measurement of baPWV thus appears to be more useful than direct PWV for evaluating ACL (>4.0 mm).

In earlier studies of coronary artery disease (CAD), a large number of patients with PAD had already suffered CAD, but only 15% of patients with CAD had PAD.26 In addition, 24% of patients with ACL had PAD.3 In the present study, PAD (ABI<0.9) was more frequent in the ACL group than in the non-ACL group (18 vs. 4%), whereas most patients (73%) with PAD had ACL. It thus appears that the aorta is more likely to be affected by atherosclerosis than peripheral arteries. The presence of PAD may indicate the terminal stage of systemic atherosclerosis.27, 28, 29

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, the independent factors associated with ACL were age, smoking and the presence of PAD. Age and smoking were earlier reported to be risk factors for ACL. We devised an ACL scale score by adding the new predictor, presence of PAD, to the well-known risk factors, age and smoking. The ACL scale score produced from these three variables was useful for predicting the presence of ACL. Although ACL should be examined in patients with stroke of unknown etiology, it is difficult to perform TEE for all patients with acute stroke. The ACL scale score thus appears to be useful for predicting the presence of ACL as well as the choice of treatment for acute stroke.

We have usually administered anticoagulants for patients with mobile plaque and antiplatelet agents for those without it. Earlier studies reported a potential benefit of anticoagulation.30, 31 On the other hand, Tunick et al.32 found no significant benefit of anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs for patients with ACL. A large prospective study is needed to determine which of these are better for patients with ACL.

Our study has some limitations. First, selection bias may have affected the rate of detection of ACL in our series, as we were unable to perform TEE for all stroke patients. Second, only four patients had an ACL scale score of 4. To confirm the accuracy of the ACL scale, examination with a larger sample size is needed.

In conclusion, age, carotid IMT, PWV and ABI all exhibited strong associations with ACL (>4.0 mm) in stroke patients. An ACL scale composed of three variables, (1) over 70 years of age, (2) presence of PAD and (3) smoking, could predict the presence of ACL.

References

Amarenco P, Duyckaerts C, Tzourio C, Henin D, Bousser MG, Hauw JJ . The prevalence of ulcerated plaques in the aortic arch in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 221–225.

Amarenco P, Cohen A, Tzourio C, Bertrand B, Hommel M, Besson G, Chauvel C, Touboul PJ, Bousser MG . Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch and the risk of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1474–1479.

The French Study of Aortic Plaques in Stroke Group. Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch as a risk factor for recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1216–1221.

Fujimoto S, Yasaka M, Otsubo R, Oe H, Nagatsuka K, Minematsu K . Aortic arch atherosclerotic lesions and the recurrence of ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004; 35: 1426–1429.

Ueno Y, Kimura K, Iguchi Y, Shibazaki K, Inoue T, Hattori N, Urabe T . Mobile aortic plaques are a cause of multiple brain infarcts seen on diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2007; 38: 2470–2476.

Meissner I, Whisnant JP, Khandheria BK, Spittell PC, O'Fallon WM, Pascoe RD, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, Covalt JL, Sicks JD, Wiebers DO . Prevalence of potential risk factors for stroke assessed by transesophageal echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography: The sparc study. Stroke prevention: Assessment of risk in a community. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 862–869.

Toyoda K, Yasaka M, Nagata S, Yamaguchi T . Aortogenic embolic stroke: a transesophageal echocardiographic approach. Stroke 1992; 23: 1056–1061.

Inoue T, Oku K, Kimoto K, Takao M, Nomoto J, Handa K, Kono S, Arakawa K . Relationship of cigarette smoking to the severity of coronary and thoracic aortic atherosclerosis. Cardiology 1995; 86: 374–379.

Jones EF, Kalman JM, Calafiore P, Tonkin AM, Donnan GA . Proximal aortic atheroma. An independent risk factor for cerebral ischemia. Stroke 1995; 26: 218–224.

Matsuzaki M, Ono S, Tomochika Y, Michishige H, Tanaka N, Okuda F, Kusukawa R . Advances in transesophageal echocardiography for the evaluation of atherosclerotic lesions in thoracic aorta—the effects of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and aging on atherosclerotic lesions. Jpn Circ J 1992; 56: 592–602.

Kessler C, Mitusch R, Guo Y, Rosengart A, Sheikhzadeh A . Embolism from the aortic arch in patients with cerebral ischemia. Thromb Res 1996; 84: 145–155.

Shimizu Y, Kitagawa K, Nagai Y, Narita M, Hougaku H, Masuyama T, Matsumoto M, Hori M . Carotid atherosclerosis as a risk factor for complex aortic lesions in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Circ J 2003; 67: 597–600.

Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, Schwartz GL, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Whisnant JP, Wiebers DO, Seward JB . Relation of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease with atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta in the general population. Am J Cardiol 2002; 89: 262–267.

Yamashina A, Tomiyama H, Takeda K, Tsuda H, Arai T, Hirose K, Koji Y, Hori S, Yamamoto Y . Validity, reproducibility, and clinical significance of non-invasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement. Hypertens Res 2002; 25: 359–364.

van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Witteman JC . Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2001; 32: 454–460.

Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor Jr LM, White CJ, White J, White RA, Antman EM, Smith Jr SC, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B . Acc/aha 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): A collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the acc/aha task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; Transatlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006; 113: e463–e654.

O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson Jr SK . Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular health study collaborative research group. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 14–22.

Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, Ohira T, Okada T, Sato S, Kiyama M, Tanigawa T, Yamagishi K, Shimamoto T . Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque characteristics as a risk factor for stroke in Japanese elderly men. Stroke 2004; 35: 2788–2794.

Adams Jr HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh III EE . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Toast. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 1993; 24: 35–41.

Koji Y, Tomiyama H, Ichihashi H, Nagae T, Tanaka N, Takazawa K, Ishimaru S, Yamashina A . Comparison of ankle-brachial pressure index and pulse wave velocity as markers of the presence of coronary artery disease in subjects with a high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2004; 94: 868–872.

Touboul PJ, Elbaz A, Koller C, Lucas C, Adrai V, Chedru F, Amarenco P . Common carotid artery intima-media thickness and brain infarction: the etude du profil genetique de l'infarctus cerebral (genic) case-control study. The genic investigators. Circulation 2000; 102: 313–318.

Bots ML, Hoes AW, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Grobbee DE . Common carotid intima-media thickness and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: The Rotterdam Study. Circulation 1997; 96: 1432–1437.

del Sol AI, Moons KG, Hollander M, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Grobbee DE, Breteler MM, Witteman JC, Bots ML . Is carotid intima-media thickness useful in cardiovascular disease risk assessment? The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2001; 32: 1532–1538.

Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, Asmar R, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, Breteler MM, Witteman JC . Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: The Rotterdam Study. Circulation 2006; 113: 657–663.

van Popele NM, Mattace-Raso FU, Vliegenthart R, Grobbee DE, Asmar R, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, de Feijter PJ, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC . Aortic stiffness is associated with atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries in older adults: The Rotterdam Study. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 2371–2376.

Kawarada O, Yokoi Y, Morioka N, Nakata S, Higashiue S, Mori T, Iwahashi M, Hatada A . Carotid stenosis and peripheral artery disease in Japanese patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Circ J 2003; 67: 1003–1006.

Valentine RJ, Grayburn PA, Eichhorn EJ, Myers SI, Clagett GP . Coronary artery disease is highly prevalent among patients with premature peripheral vascular disease. J Vasc Surg 1994; 19: 668–674.

Caprie Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (caprie). Lancet 1996; 348: 1329–1339.

Harloff A, Strecker C, Reinhard M, Kollum M, Handke M, Olschewski M, Weiller C, Hetzel A . Combined measurement of carotid stiffness and intima-media thickness improves prediction of complex aortic plaques in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2006; 37: 2708–2712.

Dressler FA, Craig WR, Castello R, Labovitz AJ . Mobile aortic atheroma and systemic emboli: Efficacy of anticoagulation and influence of plaque morphology on recurrent stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31: 134–138.

Ferrari E, Vidal R, Chevallier T, Baudouy M . Atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta and aortic debris as a marker of poor prognosis: Benefit of oral anticoagulants. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 33: 1317–1322.

Tunick PA, Nayar AC, Goodkin GM, Mirchandani S, Francescone S, Rosenzweig BP, Freedberg RS, Katz ES, Applebaum RM, Kronzon I . Effect of treatment on the incidence of stroke and other emboli in 519 patients with severe thoracic aortic plaque. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90: 1320–1325.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terasawa, Y., Kimura, K., Iguchi, Y. et al. Predictors of aortic complicated lesions in stroke patients. Hypertens Res 32, 462–465 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.53

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.53