Abstract

Moxonidine is a selective imidazoline receptor agonist with comparable blood pressure-lowering efficacy to first-line antihypertensives and favorable metabolic effects. YKL-40 (chitinase-3-1-protein) has been proposed as a new marker of inflammation, atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction in neoplastic, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases but has not yet been studied in the context of essential hypertension. Fifteen patients (10 M, 5 F; age 48±14 years) with arterial hypertension and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR index >2.77) on at least two antihypertensive drugs were randomized to receive either moxonidine (0.4 mg) or amlodipine (10 mg) for two 8-week periods with a 7-day wash-out. Serum insulin, glucose, C-reactive protein (CRP), lipids, uric acid, YKL-40 and blood pressure were measured and insulin sensitivity was calculated (HOMA) at the beginning and end of each study phase. Mean BP decreased significantly with both moxonidine and amlodipine (−9.8±7.6 and −10.4±7.3 mm Hg, respectively). Serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol increased with both therapies, but only moxonidine-affected serum triglycerides. No significant changes in serum uric acid, CRP, YKL-40 (2.3 and 3.3 ng ml–1, respectively) or HOMA index (0.70±2.4 and 0.76±2.8) were observed. There was a strong negative correlation between serum uric acid and YKL-40 concentration at baseline (r=−0.77, P=0.01). Serum YKL-40 did not correlate with blood pressure, biochemical parameters or HOMA index. Moxonidine is an effective adjunctive antihypertensive agent for use in patients with hypertension and insulin resistance that induces beneficial effects on serum lipid profile but does not reduce insulin resistance, inflammation or serum YKL-40 concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moxonidine is a centrally active antihypertensive drug acting as a selective agonist at imidazoline receptor subtype 1.1, 2 Moxonidine decreases sympathetic nervous system activity and thereby induces a hypotensive effect similar to other classes of antihypertensives with equal or even better tolerability profiles.1 In particular, common side effects of centrally acting antihypertensives such as dizziness and dry mouth are much less frequent after moxonidine.1 Moreover, imidazoline receptor agonists in contrast to other centrally acting drugs may lack antinatriuretic effects that could limit their blood pressure-lowering efficacy.3 Furthermore, moxonidine has not been associated with undesirable metabolic effects in hypertension and may even have favorable effects on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity.4 The compound can also improve endothelial dysfunction.5 It was also postulated that moxonidine may have potent anti-inflammatory properties, most probably secondary to a decrease in sympathetic activity.6

We compared moxonidine to amlodipine, a channel blocker that is recognized as the first-line antihypertensive drug. Amlodipine selectively inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels in both cardiac muscle and blood vessels and therefore its main effects are derived from vasodilatory and cardiodepressant actions. Amlodipine has frequently been used in cardiovascular clinical trials as a reference agent because of its metabolic neutrality.7

Very recently, YKL-40 (chitinase-3-like-1-protein) was proposed as a new marker of inflammation, atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction in various neoplastic, cardiovascular and metabolic disease states including type I and II diabetes.8, 9 Interestingly, this new serum marker has not yet been studied in essential arterial hypertension.

YKL-40 is a member of the chitinase protein family that is produced locally by activated macrophages, chondrocytes, synoviocytes and neutrophils.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Although the physiological role of YKL-40 is unknown, the pattern of its expression in normal and disease states suggests a function in remodeling or degradation of the extracellular matrix.13, 14 YKL-40 is increasingly recognized as a marker of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction and it seems to be of pathogenic importance in the low-grade inflammation that may precede the development of cardiovascular disease.9 This hypothesis was recently verified in clinical settings in patients with coronary artery disease.15 Two recent studies demonstrated significantly elevated levels of YKL-40 in patients with type II diabetes as well as a positive correlation with insulin resistance and lipid disturbances.8, 9

This study was carried out to test the possibility that antihypertensive treatment with moxonidine may induce more favorable effects than the dihydropyridine calcium antagonist amlodipine on insulin resistance, serum lipids, uric acid and a new cardiovascular risk marker, YKL-40.

Methods

Study design

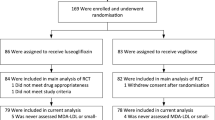

The study was designed as a double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. All patients were randomized to receive either moxonidine (0.4 mg day–1 in a single morning dose) or amlodipine (10 mg day–1 in a morning dose) orally for the first 8 weeks of the study. Then after a 7-day wash-out period patients received amlodipine or moxonidine for another 8 weeks in accordance with a crossover design. Study visits occurred four times during the study, that is, before and at the end of each treatment period. The same investigator performed all visits and measurements during the study. Patient compliance was checked by pill counting at each visit. Both the patients and the investigator remained blinded for the entire study duration. The Local Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. All subjects provided informed consent before any study-related procedures.

Patients

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of the study subjects at baseline are given in Table 1. The study group comprised 15 patients with diagnosis of arterial hypertension (5 females, 10 males; mean age 48±14 years) who were chronically (for at least the preceding 6 months) treated with at least two different first-line antihypertensive drugs, excluding calcium antagonists and central sympatholytics. Antihypertensive drugs used by the patients at baseline and in consistent doses throughout the entire study comprised angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (11 patients), angiotensin II receptor blockers (seven patients), loop (10 patients) and thiazide (five patients) diuretics, beta-blockers (13 patients) and α-blockers (four patients). The main inclusion criteria were age 18–75 years, sitting diastolic and systolic blood pressure below 120 and 180 mm Hg, respectively, and insulin resistance (defined as HOMA-IR value >2.7716). Exclusion criteria were clinical or laboratory evidence of secondary hypertension; insulin-treated diabetes mellitus; proteinuria ⩾0.3 g/24 h; estimated glomerular filtration rate, simplified MDRD formula, <60 ml min–1 1.73 m–2; chronic heart failure (NYHA stage III or IV); liver insufficiency; and previous intolerance to calcium antagonists or imidazoline receptor agonists. Except for study-related medication the doses of all other drugs were unchanged throughout the study.

Blood pressure and heart rate

The office blood pressure (BP) and heart rate were recorded four times, that is, before and at the end of each treatment period, using a mercury sphygmomanometer with the patient in a sitting position after 15 min of rest (three consecutive measurements with 3 min intervals at each visit). The same person measured blood pressure every time. Mean blood pressure was calculated for all measurements as diastolic BP+1/3 of pulse pressure (systolic BP−diastolic BP).

Biochemical parameters

For each subject, the following plasma biochemical parameters were obtained at each study visit: insulin, glucose, CRP (C-reactive protein), lipids (total, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides), uric acid and YKL-40. The HOMA index was calculated from fasting plasma glucose and serum insulin according to the standard formula (HOMA-IR=plasma glucose(mmol l–1) × serum insulin/22.5). Body weight and (Body Mass Index) were estimated during each visit.

Serum YKL-40 concentration was measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the commercially available test MicroVue YKL-40 (Quidel, San Diego, CA, USA). All other parameters were measured with standard laboratory automated methods.

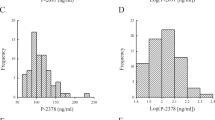

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means±s.d. Statistical significance was defined at P<0.05. The normality of data distribution was checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and non-normally distributed data were logarithmically transformed before analysis. The within-group comparisons were performed using t-test or Wilcoxon's test. The Pearson or Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to assess relations between the variables. Statistical analysis of treatment outcome was carried out using the parametric approach to crossover trials, including the evaluation of potential carryover effects in accordance with recent recommendations.17 Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica for Windows (version 6.0, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

All patients finished the study and no clinically important side effects were observed for either therapy, with the exception of transient mild ankle edema in two patients during treatment with amlodipine.

Blood pressure, heart rate and body mass

A significant decrease in systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure was observed during treatment with both moxonidine and amlodipine. The difference between blood pressure changes during treatment with moxonidine compared with amlodipine was not significant for systolic (−15.8±17.1 vs. −12.3±8.0 mm Hg; P=0.44), diastolic (−7.3±−8.6 vs. 9.4±9.2 mm Hg; P=0.29) or mean arterial pressure (−9.8±7.6 vs. −10.4±7.3 mm Hg; P=0.69). Figure 1 shows systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure during the study.

Heart rate was unchanged during treatment with moxonidine (76±13 before vs. 80±11 b.p.m. after 8 weeks of treatment) and amlodipine (79±11 vs. 76±12 b.p.m., respectively).

Body weight decreased significantly during treatment with moxonidine (from 84.0±20.6 to 83.1±20.4 kg; P=0.001). In contrast, body weight significantly increased after the administration of amlodipine (from 83.5±20.4 to 84.3±20.5 kg; P=0.01).

Biochemical parameters

Table 2 shows the effect of moxonidine on serum concentrations of lipids, uric acid and C-reactive protein.

Serum HDL cholesterol increased significantly after treatment with both moxonidine (P=0.03) and amlodipine (P=0.02). Serum triglycerides decreased after treatment with moxonidine (P=0.02), but not amlodipine (P=0.37). No significant changes in serum total cholesterol or LDL cholesterol were found during the study. The HDL/LDL cholesterol ratio increased by 9.2±11.5% (after moxonidine) and decreased by 3.1±8.9% after amlodipine (P=0.02). No changes in serum uric acid or serum C-reactive protein were observed.

Serum levels of YKL-40 remained virtually unchanged during both treatments (Figure 2).

Treatment with both moxonidine and amlodipine did not change serum concentrations of insulin and plasma glucose. The mean change in serum insulin after moxonidine therapy was 0.2±7.4 mU l–1 (P=0.90); after amlodipine this value was −7.2±3.6 mU l–1 (P=0.87). The mean change in plasma glucose was 3.4±15.9 (P=0.42) and 2.9±10.8 mg dl–1 (P=0.32), respectively.

The HOMA index did not change after treatment with moxonidine (4.5±2.0 vs. 5.2±3.0 before and after treatment, respectively; P=0.27) or amlodipine (7.1±3.6 vs. 7.9±4.1, respectively; P=0.32). The mean changes in the HOMA index during treatment with moxonidine and amlodipine were almost identical (0.70±2.4 and 0.76±2.8, respectively). Figure 3 shows individual changes in the HOMA index during both phases of the study.

There was also a strong negative correlation between serum uric acid and YKL-40 concentration assessed at baseline (r=−0.77, P=0.01) (Figure 4) in comparison to the baseline concentration of uric acid and the change in serum uric acid during treatment with amlodipine (r=0.74, P=0.01). Serum YKL-40 did not significantly correlate with blood pressure, any other biochemical parameter or the HOMA index.

Discussion

Moxonidine is a second-line antihypertensive drug affecting the central nervous system that decreases peripheral vascular resistance by blocking sympathetic activity.1, 2 This drug has drawn considerable interest since its introduction in 1992 due to favorable metabolic effects, a profile that contrasts with those of other centrally active sympatholytic agents.1

The effect of moxonidine and its close relative, rilmenidine, on blood pressure and metabolic profile was assessed in several clinical trials, mostly in subjects with arterial hypertension complicated by various metabolic or endocrine abnormalities (for example, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, menopause).18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Despite the well-proven blood pressure-lowering efficacy of moxonidine and the closely related rilmenidine, the number of trials with head-to-head comparisons to other antihypertensive drugs has been limited. In most clinical trials those agents were used as adjuvant therapy.18, 26 We have been able to identify only three small studies in which the imidazoline receptor agonist was directly compared with the calcium antagonist.19, 20, 21 All of these studies included patients with arterial hypertension complicated by either metabolic syndrome or obesity.

The choice of patients included in our study was driven by the results of clinical trials which showed that moxonidine is particularly useful in patients with hypertension and insulin resistance. We compared this drug to amlodipine, which is a widely used first-line antihypertensive drug and is recognized by most clinicians as metabolically neutral.7

The decrease in blood pressure achieved by both drugs in our study was comparable, and therefore it seems that any potential differences in their effects cannot be explained by differences in blood pressure-lowering efficacy. One of the potential limitations of our study is low patient number, but this could be partially compensated for by the crossover design of the trial.17 The mean decrease of both systolic and diastolic blood pressure observed in our study during therapy with both moxonidine and amlodipine was similar to that reported by De Luca et al.21 De Luca et al.21 used another imidazoline receptor agonist, rilmenidine, which yielded values only slightly lower than those reported by Sanjuliani et al.19 This latter study used the same dose of moxonidine, but their subjects had much higher blood pressure at baseline than was observed in our study, which could explain the difference.

The only clear difference in the effects of moxonidine and amlodipine in our study was observed in cases when body weight decreased with the former treatment but increased with the latter. The small but significant increase of body weight in patients on amlodipine in our study could be explained by the development of subclinical edema and fluid retention, which are well-known complications of calcium antagonist use.27 In contrast, the body weight decrease observed after moxonidine treatment may have resulted from several mechanisms. The first may be a lack of the antinatriuretic response to a drop in blood pressure, which is a phenomenon that we first described in 1995.3 The other likely explanation is an increase in atrial natriuretic peptide secretion, which was observed after the administration of moxonidine in several experimental studies.28, 29 Other investigators did not find a significant decrease in body weight during the treatment of hypertensive patients with obesity or obesity and metabolic syndrome with either moxonidine19 or rilmenidine.21 However, in both studies there was a trend toward increased body weight during amlodipine therapy and decreased body weight during imidazoline receptor agonist administration.

We were also able to show a decrease in serum triglycerides and an increase in HDL-cholesterol after moxonidine therapy, which is concordant with previous observations.30 Recent studies suggested that moxonidine inhibits de novo fatty acid synthesis. Activation of imidazoline receptor lowers plasma lipids, with the main site of action likely within the liver, so as to reduce the synthesis and secretion of triglycerides.31 In contrast to most of the previous studies, we did not observe any changes in the HOMA index. This index is a widely used and simple method to study insulin resistance that shows a good correlation with the gold standard method, the euglycemic clamp technique.32 Moxonidine has been shown to partially restore glucose tolerance in fructose-fed rats subjected to a glucose load and to normalize insulin levels in this model,33 as well as in spontaneously hypertensive rats.34 Further experimental studies provided more evidence of increased sympathetic nervous activity as a common denominator in both hypertension and insulin resistance and also confirmed the beneficial effect of moxonidine on both BP and glucose control.35 A decrease in insulin resistance was also shown after moxonidine therapy in hypertensive patients with the euglycemic clamp technique.4 We also observed an improvement in glucose tolerance after oral glucose loading.19, 36 However, another recent study using both HOMA to study insulin resistance and an oral glucose tolerance test was not able to confirm such beneficial effects (with another imidazoline receptor agonist rilmenidine).20 It is also of note that the beneficial effect of moxonidine observed in several small clinical studies on insulin resistance has never been confirmed by a large randomized trial.

Derosa et al.37 carried out a study in 99 patients with type II diabetes mellitus and mild previously untreated hypertension. This study showed a significant decrease from baseline in fasting plasma glucose, fasting plasma insulin, HOMA index and triglycerides, as well as an increase in HDL-C after 6 months of moxonidine (0.4 mg per day). Although our study was shorter in duration, similar changes were observed with regard to hypertension control, serum triglycerides and HDL-C.

To date there have been no studies that investigated either the role of YKL-40 in the pathophysiology of arterial hypertension or an effect of blood pressure lowering medications on serum YKL-40 levels. As previously mentioned, there is a growing body of evidence, mainly from studies carried out in patients with diabetes or coronary artery disease, that YKL-40 is a marker of atherosclerosis, inflammation and endothelial function.8, 9, 11, 15 We did not find any correlation of blood pressure decrease or change in insulin sensitivity or C-reactive protein with the change in serum YKL-40 after either therapy. We did observe a tight correlation between serum YKL-40 and serum uric acid. Such a relation has not been reported previously and its potential pathogenetic relevance is unknown but a recent renewed interest in serum uric acid as a link between endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerotic vascular disease and the development of hypertension31 makes it an attractive target for future investigations.

As our study was small, short in duration and limited to a selected population of patients with hypertension and insulin resistance, our results do not preclude a role for serum YKL-40 as a useful biomarker of cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. This issue will require further study.

We conclude that moxonidine is an effective adjunctive antihypertensive agent for use in patients with essential hypertension and insulin resistance.25 Moxonidine may induce some beneficial effects with respect to serum lipid profile, but did not reduce insulin resistance or inflammation or affect serum YKL-40 concentration—a new marker of endothelial function, inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Schachter M . Moxonidine: a review of safety and tolerability after seven years of clinical experience. J Hypertens Suppl 1999; 17: S37–S39.

Ernsberger P, Damon TH, Graff LM, Schäfer SG, Christen MO . Moxonidine, a centrally acting antihypertensive agent, is a selective ligand for I1-imidazoline sites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993; 264: 172–182.

Wiêcek A, Fliser D, Nowicki M, Ritz E . Effect of moxonidine on urinary electrolyte excretion and renal haemodynamics in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 48: 203–208.

Haenni A, Lithell H . Moxonidine improves insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant hypertensives. J Hypertens Suppl 1999; 17: S29–S35.

Topal E, Cikim AS, Cikim K, Temel I, Ozdemir R . The effect of moxonidine on endothelial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2006; 6: 343–348.

Pöyhönen-Alho MK, Manhem K, Katzman P, Kibarskis A, Antikainen RL, Erkkola RU, Tuomilehto JO, Ebeling PE, Kaaja RJ . Central sympatholytic therapy has anti-inflammatory properties in hypertensive postmenopausal women. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 2445–2449.

Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Mancia G, for VALUE Trial Investigators. Effects of valsartan compared to amlodipine on preventing type 2 diabetes in high-risk hypertensive patients: the VALUE trial. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 1405–1412.

Rathcke CN, Persson F, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Vestergaard H . YKL-40, a marker of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, is elevated in patients with type 1 diabetes and increases with levels of albuminuria. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 323–328.

Rathcke CN, Vestergaard H . YKL-40, a new inflammatory marker with relation to insulin resistance and with a role in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Inflamm Res 2006; 55: 221–227.

Nyikros P, Golds EE . Human synovial cells secrete a 39 kDa protein similar to a bovine mammary protein expressed during the non-lactating period. Biochem J 1990; 268: 265–268.

Baeten D, Boots AM, Steenbakkers PG, Elewaut D, Bos E, Verheijden GF, Berheijden G, Miltenburg AM, Rijnders AW, Veys EM, De Keyser F . Human cartilage gp-39+, CD 16+ monocytes in peripheral blood and synovium: correlation with joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 1233–1243.

Millis AJ, Hoyle M, Kent L . In vitro expression of a 38 000 dalton heparin-binding glycoprotein by morphologically differentiated smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 1986; 127: 366–372.

Malinda KM, Ponce L, Kleinman HK, Shackelton LM, Millis AJ . Gp38k, a protein synthesized by vascular smooth muscle cells, stimulates directional migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 1999; 250: 168–173.

Shackelton LM, Mann DM, Millis AJ . Identification of a 38-kDa heparin-binding glycoprotein (gp38k) in differentiating vascular smooth muscle cells as a member of a group of proteins associated with tissue remodeling. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 13076–13083.

Kastrup J, Johansen JS, Winkel P, Hansen JF, Hildebrandt P, Jensen GB, Jespersen CM, Kjøller E, Kolmos HJ, Lind I, Nielsen H, Gluud C, CLARICOR Trial Group. High serum YKL-40 concentration is associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1066–1072.

Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Targher G, Alberiche M, Bonadonna RC, Muggeo M . Prevalence of insulin resistance in metabolic disorders: the Bruneck Study. Diabetes 1998; 47: 1643–1649.

Mills EJ, Chan A-W, Wu P, Vail A, Guyatt GH, Altman DG . Design, analysis, and presentation of crossover trials. Trials 2009; 10: 1–6.

Rayner B . Selective imidazoline agonist moxonidine plus the ACE inhibitor ramipril in hypertensive patients with impaired insulin sensitivity: partners in a successful MARRIAGE? Curr Med. Res Opin 2004; 20: 359–367.

Sanjuliani AF, de Abreu VG, Fransischetti EA . Selective imidazoline agonist moxonidine in obse hypertensive patients. Int J Clin Pract 2006; 60: 621–629.

Widimsky J, Siritiakova J . Efficacy and tolerability of rilmenidine compared with isradipine in hypertensive patients with features of metabolic syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22: 1287–1294.

De Luca N, Izzo R, Fontana D, Iovino G, Argenziano L, Vecchione C, Trimarco B . Haemodynamic and metabolic effects of rilmenidine in hypertensive patients with metabolic syndrome X. A double-blind parallel study versus amlodipine. J Hypertens 2000; 18: 1515–1522.

Jacob S, Klimm HJ, Rett K, Helsberg K, Häring HU, Gödicke J . Effects of moxonidine vs metoprolol on blood pressure and metabolic control in hypertensive subject with type 2 diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2004; 112: 315–322.

Monography. Moxonidine improves glycaemic control in mildly hypertensive, overweight patients: a comparison with metformin. Solvay Pharmaceuticals: Hannover, 2005.

Kaaja R, Manhem K, Tuomilehto J . Treatment of postmenopausal hypertension with moxonidine, a selective imidazoline receptor agonista. Int J Clin Pract 2004; 139: 26–32.

Pater C, Bhatnagar D, Berrou J-P, Luszick J, Beckmann K . A novel approach to treatment of hypertension in diabetic patients: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study comparing the efficacy of combination therapy of eposartan versus ramipril with low dose hydrochlorothiazide and moxonidine on blood pressure levels in patients with hypertension and associated diabetes mellitus type 2. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med 2004; 5: 9–16.

Fenton C, Keating GM, Lyseng-Williamson KA . Moxonidine: a review of its use in essential hypertension. Drugs 2006; 66: 477–496.

Messerli FH . Vasodilatatory oedema: a common side effect of antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens 2001; 14: 978–979.

El-Ayoubi R, Menaouar A, Gutkowska J, Mukaddam-Daher S . Urinary responses to acute moxonidine are inhibited by natriuretic peptide receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol 2005; 45: 50–56.

Cao C, Kang CW, Kim SZ, Kim SH . Augmentation of moxonidine—induced increase in ANP release by atrial hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004; 287: H150–H156.

Lumb PJ, McMahon Z, Chik G, Wierzbicki AS . Effect of moxonidine on lipid subfractions in patients with hypertension. Int J Clin Pract 2004; 58: 465–468.

Strazzullo P, Puig JG . Uric acid and oxidative stress: relative impact on cardiovascular risk? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2007; 17: 09–414.

Bonora E, Targher G, Alberiche M, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, Lombardi S, Marini F, Poli M, Zenari L, Raffaelli A, Perbellini S, Zenere MB, Saggiani F, Bonadonna RC, Muggeo M . Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degree of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 57–63.

Kaan EC, Brückner R, Frohly P, Tulp M, Schäfer S, Ziegler D . Effects of agmatine and moxonidine on glucose metabolism: an integrated approach towards pathophysiological mechanisms in cardiovascular metabolic disorders. J Card Risk Fact 1995; 5: 10–27.

Rösen P, Ohly P, Gleichmann H . Experimental benefit of moxonidine on glucose metabolism and insulin secretion in the fructose-fed rat. J Hypertens 1997; 15: S31–S38.

Ernsberger P, Ishizuka T, Liu S, Farrell CJ, Bedol D, Koletsky RJ, Friedman JE . Mechanisms of antihyperglycemic effects of moxonidine in the obese spontaneously hypertensive Koletsky rat (SHROB). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 288: 139–147.

Chazova I, Almazov VA, Shlyakhto E . Moxonidine improves glycaemic control in mildly hypertensive, overweight patients: a comparison with metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab 2006; 8: 456–465.

Derosa G, Cicero AF, D’Angelo A, Fogari E, Salvadeo S, Gravina A, Ferrari I, Fassi R, Fogari R . Metabolic and antihypertensive effects of moxonidine and moxonidine plus irbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and mild hypertension: a sequential, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Ther 2007; 29: 602–610.

Acknowledgements

This reserach was supported by Medical University of Łódź grant No. 503-1151-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masajtis-Zagajewska, A., Majer, J. & Nowicki, M. Effect of moxonidine and amlodipine on serum YKL-40, plasma lipids and insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant hypertensive patients—a randomized, crossover trial. Hypertens Res 33, 348–353 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2010.6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Significance of chitinase-3-like protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and cancer

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2024)

-

YKL-40 promotes the progress of atherosclerosis independent of lipid metabolism in apolipoprotein E−/− mice fed a high-fat diet

Heart and Vessels (2019)

-

Association between human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (YKL-40) and arterial stiffness in essential hypertension

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2012)

-

A Score for the Prediction of Cardiovascular Events in the Hypertensive Aged

American Journal of Hypertension (2012)