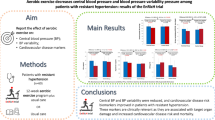

Abstract

The factors which contribute to an exaggerated blood pressure response (EBPR) during the exercise treadmill test (ETT) are not wholly understood. The association between the insertion/deletion polymorphisms of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and M235T of the angiotensinogen with EBPR during ETT still remains unstudied. To identify and compare the risk factors for hypertension between normotensive subjects with EBPR and those who exhibit a normal curve of blood pressure (BP) during ETT. In a series of EBPR cases from a historical cohort of normotensive individuals, a univariate analysis was performed to estimate the association of the studied factors with BP behavior during ETT. Additionally, logistic multivariate regression was conducted to analyze the joint effects of the variables. P-values above 0.05 were considered statistically significant. From a total of 10 027 analyzed examinations, only 219 met the criteria employed to define EBPR, which resulted in a prevalence of 12.6%. For the systolic component of the BP, hyperreactive subjects displayed a mean age and body mass index (BMI) significantly higher than the others (P=0.002 and <0.001, respectively). No association was observed between the polymorphisms cited above and EBPR. An analysis of the joint effect of variables has indicated that only age (P< 0.001) and BMI (P=0.001) were specifically associated with systolic BP during exercise. Age and BMI were the only factors that independently influenced EBPR during ETT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neither the physiopathological mechanisms involved in the way blood pressure (BP) responds to exercise, nor the factors that contribute to exaggerated BP response (EBPR) during exercise treadmill testing (ETT) are fully understood. Comparisons between normoreactive and hyperreactive patients, considering socio-demographic and clinical features, have mostly been carried out in small cohorts, using nonstandard criteria, which may have significantly influenced the results. Several authors have compared small normoreactive and hyperreactive cohorts but while these groups have been assessed with regard to cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose levels, smoking habits and alcohol consumption, no differences were observed between the groups.1, 2, 3, 4 However, Jae et al.5 observed statistically significant differences regarding all the above-mentioned variables (with the exception of alcohol) when comparing 8969 normoreactive and 375 hyperreactive patients.

It has been shown that responses to physical exercise vary amongst individuals, suggesting that the outcome of exercise might be affected by genetic variations.6 Similarly, several genes that encode for proteins of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system have been shown to have a role in the aetiopathogeny of hypertension. However, there are conflicting results within the studies that have assessed the relationship between the polymorphisms in these genes and hypertension. Some analyses have shown that the D allele of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene increases the threshold of developing hypertension. On the other hand, other studies have described the I allele as being responsible for the phenotype or even a lack of association between this polymorphism and hypertension. Contradictory findings have also been described concerning an association between the M235T polymorphism of the angiotensinogen gene (AGT) and hypertension.7 However, to date, any association between such polymorphisms and EBPR during ETT has remained unstudied.

Considering that hyperreactive individuals are four to five times more likely to develop hypertension,8, 9, 10 and that primary healthcare strategies have already been established as an effective prevention for this disease, understanding and developing forms of combating the risk factors that influence EBPR are fundamental for preventing hypertension and circulatory system diseases.

Therefore, the objective of this study has been to describe and compare the frequency of risk factors for hypertension (genetic and environmental), as well as the hemodynamic and functional variables of ETT among normotensive individuals who display EBPR and those with normal BP during ETT.

Methods

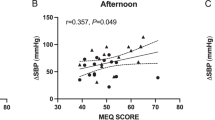

This was a series of EBPR cases from a historical cohort of normotensive subjects who underwent ETT at the beginning of the study. A group, composed of individuals who presented abnormal BP behavior during exercise (Δ SBP ⩾7.5 mm Hg per metabolic equivalent (MET) and/or systolic BP (SBP) at the peak of the exercise ⩾220 mm Hg or Δ DBP ⩾15 mm Hg, starting from normal BP levels at rest) was compared with another in which patients displayed normal BP during physical exercise. Any patients taking antihypertensives or any other drugs, which could potentially interfere with BP behavior or heart rate (HR), individuals undergoing diagnostic investigation for hypertension or those who even after meeting inclusion criteria, presented any thoracic discomfort or localized pain, cardiac rhythm or conduction disturbances, or any suspicion of electrocardiographic alterations of miocardic ischemia, patients who presented pulmonary congestion or broncospasm during ETT and those who did not reach submaximal HR during exercise, were all excluded from the study. The BP behavior under exercise was analyzed as a dependent variable. Genetic polymorphism and classic risk factors for hypertension (diabetes mellitus; DM, hypercholesterolemia, hypertrigliceridemia, patients whose immediate relatives have been affected by hypertension, skin color and body mass index; BMI) were analyzed as independent variables. Furthermore, the analysis was stratified considering the EBPR subgroups: reactive hypertensive individuals through the systolic component (SRH) and reactive hypertensive individuals through the diastolic component (DRH).

The study protocol was approved by the CPqAM-FIOCRUZ ethics committee and all participants signed the terms of consent.

The ETT analysis was conducted by one single physician, using the ramp protocol.11 BP was measured, both at rest and during exercise, using a mercury sphingomanometer. Measurements were taken at regular 3-min intervals during the exercise phase and during the first, second, fourth and sixth minutes of the recovery phase. For SBP, phase ‘1’ of the Korotkoff sounds was considered and for diastolic BP (DBP) phase ‘5’.

All patients enrolled on this study were sent to a clinical analysis laboratory, where blood samples were collected and DNA was extracted with standard salting out protocols. The genomic region of the polymorphisms considered for investigation during this study were amplified by PCR with the following primers for AGT FW 5′-GGA AGG ACA AGA ACT GCA CCT C-3′ and RV 5′-CAG GGT GCT GTC CAC ACT GGA CCC C-3′12 and for ACE FW 5′-CYG GAG ACC ACT CCC ATC CTT TCT-3′ and RV 5′-GAT GTG GCC ATC ACA TTC GTC AGA T-3′.13 To verify the ACE allelic distribution throughout the cohort, 1.5% agarose was employed. After amplifying the AGT region of interest, PCR products were purified enzymatically, using exoquinase and shrimp alkaline phosphatases. Following this, the purified products were sequenced in a MegaBACE 1000. Univariate analysis was conducted in order to evaluate the association of each independent variable with BP behavior during ETT. Multivariate logistic regression was carried out to evaluate the joint effect of the variables. Results that presented descriptive levels (P-value) below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was also tested and the χ2 test was employed to verify if the allelic frequencies were in accordance with those predicted by the equation. A possible occurrence of selection bias in this study could be minimized as long as the normoreactive and hyperreactive individuals were selected from the same population. Memory and information bias may have occurred during data collection concerning lifestyle and morbid antecedents, particularly self-reported hypercholesterolemia, hypertrigliceridemia and DM, which were not measured by biochemical tests.

Results

From the 10 027 analyzed examinations, only 219 were identified as hyperreactive, which therefore yielded a prevalence of 12.6%.

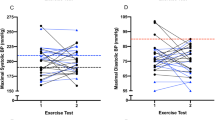

SBP and diastolic BP (DBP) at rest, at the height of exercise and the pressure variation between rest and exercise, are presented in Table 1.

DBP variation from dorsal decubitus position to orthostatic position was greater in hyperreactive individuals than normoreactive (5.7 vs. 2.3 mm Hg, P<0.001). However, the same behavior was not observed with regard to SBP (5.7 vs. 3.9 mm Hg, P=0.140). With respect to HR, it was observed in the hyperreactive group that the variation associated to posture change was 11.2 bpm, whereas in the normoreactive group this variation was 9.9 bpm (P=0.266).

The HR at rest for the hyperreactive individuals both in the orthostatic or dorsal decubitus positions was similar to the normoreactive group (P=0.992 and 0.663, respectively). On the other hand, the HR measured at maximum exercise was significantly lower in the group that displayed EBPR throughout the systolic component of the BP (P<0.001). Both the groups displayed a decrease in HR during the first minute of recovery time above 12 bpm. However, in SRH, the decrease was significantly greater (P<0.001).

The ergometric treadmill ramp inclinations, speeds, maximum oxygen consumption (VO2) and equivalent metabolic rates achieved by SRH individuals were significantly lower than the normoreactive individuals, as shown in Table 2.

Information concerning the risk factors for hypertension, SRH and DRH among the normoreactive individuals, collected on entering the cohort is presented in Table 3.

The I/D polymorphisms of the ACE gene and M235T of the AGT were also investigated as risk factors for EBPR. Neither the allelic or genotypic distribution revealed any statistically significant difference between the groups (Tables 4 and 5).

The joint effect of the AGT and ACE polymorphisms on the BP during ETT was also assessed in this population. No statistically significant difference in the haplotypic distribution between the normoreactive and hyperreactive groups was observed (Table 6).

The analysis of the joint effect of variables, a family history of hypertension, BMI and age upon the BP response to exercise, was conducted through a multinomial logistic model, where the reference category was the normoreactive group. This analysis has shown that only age (P<0.001) and BMI (P=0.001) were associated with BP behavior during physical exercise. Table 7 shows that the association between age and BMI occurred specifically with the systolic component of the BP during exercise. No association was observed between the I/D polymorphisms of the ACE gene and M235T AGT with EBPR (Table 8), even after having controlled the variables age and BMI.

Discussion

Although the physiopathological effects involved in EBPR are not completely understood, the attributed risk for this condition to develop hypertension may be based on findings, which suggest that cardiovascular reactivity, by itself, brings negative outcomes, even in the absence of the clinically manifested disease.14, 15 Studies that have assessed the endothelial function of patients with EBPR have shown a significant reduction of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation capacity.3, 16, 17 These studies corroborate the hypothesis that the cardiovascular system of hyperreactive individuals worked with normal cardiac output (CO) and an increase in peripheral vascular resistance (PVR), although the normoreactive individuals responded to physical exercise with an increase of CO and and a reduction in PVR. Other hypotheses have been suggested among other factors: inflammatory mechanisms,18 neurohumoral3, 15 and poor physical condition.15, 19, 20

The higher prevalence of EBPR encountered in the present study (12.6%) in relation to that reported in the literature may be partly justified by the very stringent criteria adopted by the study in order to define EBPR, which caused the denominator to suffer an expressive reduction. Many patients were excluded in spite of having presented with EBPR, because they also had other conditions that did not meet the criteria for defining EBPR, such as abnormal BP at rest, baseline hypertension, were taking medications that could interfere with the BP behavior during exercise, felt pain or discomfort during ETT that could trigger high BP among others. The exclusion of these patients enabled us to select only the patients who presented with EBPR without any association with other non-related conditions. Jae et al.18 reported a prevalence of 4.1%; however, EBPR was defined as a higher SBP ⩾210 mm Hg, and did not take into account either the amount of physical exercise performed or the DBP. Sharabi et al.21 considered EBPR with higher SBP and DBP levels of above 200 mm Hg and 100 mm Hg, respectively. These authors found a prevalence of 6.3%. The lack of homogeneity to define EBPR may have been one of the factors influencing the prevalence variation reported in other studies.

The present study observed that SBP levels at rest, and BP and HR variations between the lying position to orthostatic, were higher in hyperreactive individuals than in normoreactive individuals. It has been demonstrated that BP levels of hyperreactive individuals, in random measures, at rest, are significantly higher than those of normoreactive individuals.2, 21 Rostrup et al.22 reported that normotensive subjects with higher tension levels at rest, show an increase in vascular reactivity to mental stress and a consistent correlation with cardiovascular risk factors. Diwan et al.,23 also verified that the BP of hypereactive individuals at rest were in the pre-hypertension category of the VII Joint National Committee.

It is possible that sympathetic tonus, assessed by HR at rest, is similar between the groups, as there was no difference in the HR at rest between the hyperreactive and normoreactive subjects. The fact that hyperreactive individuals presented a lower HR at the peak of physical exercise when compared with the normoreactive individuals, may be explained by an early interruption of the examination due to EBPR, or indeed a shorter exercise period (no statistically significant difference). Both factors cited above might also be influenced by physical characteristics such as age and BMI, which were significantly higher in the hyperreactive group. It has been described that limitrophe hypertensive subjects present EBPR and a faster HR as a response to several stress factors, in comparison with normotensive subjects.14 This could permit us to suggest that if the exercise had not been interrupted, either because of EBPR or functional limitations, the hyperreactive group would have been expected to present a higher peak HR than the normoreactive group (NR).

The slow decrease of the HR from the peak of the exercise to the first minute of recovery has been associated to a more increased risk of cardiovascular events.24, 25 It was observed, in both groups, that the decreasing HR in this period of the ETT was over 12 bpm; however, in the SRH group, this decrease was significantly more accentuated. A possible explanation for this finding might be encountered in the BP regulation mechanisms. In individuals with a normal BP response to exercise, an elevated SBP during exercises such as swimming, walking, cycling, among others, may occur proportionally to the amount of effort. A decreased PVR is balanced by an increase in CO as a way of preventing BP reductions. EBPR individuals present higher PVR during exercise; thus, it is possible that the mechanism of BP self-regulation occurs exactly opposite to that which takes place in normoreactive individuals. As a form of compensating for the higher PVR, these individuals would show a more accentuated decrease in HR, which in turn, would directly influence the CO and consequently, the BP. This hypothesis is enhanced by the finding of lower maximum VO2 in the SRH group as compared with the normoreactive group. Among the factors that restrain a greater VO2 more expressively, it is possible to highlight the CO, which in turn is influenced by HR and systolic volume.26

The evaluation of the metabolic and functional variables of the ETT allows us to conclude that SRH individuals present a lower metabolic and functional performance to that of normoreactive individuals. It is likely that age and BMI, significantly higher in the former group, may explain the ETT performance-related differences. Takamura et al.27 evaluated the ventricular function by echocardiogram in patients with and without EBPR during exercise, and concluded that, even in the absence of hypertension, hyperreactive individuals displayed diastolic dysfunction and, as a consequence, an intolerance to exercise. Sharabi et al.21 reported that the time hyperreactive individuals spent undergoing ETT was significantly shorter than in the control group.

With regard to the classic risk factors for hypertension, our results do not reveal any difference between the normoreactive and hyperreactive individuals in relation to gender and skin color. Other studies have also shown no differences in these variables, even between the normotense and hypertense groups.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Knowing that alterations provoked in the blood vessels by DM and deslipidemia gradually settled down, associated to the fact that there is no available information concerning the time of diagnosis of these risk factors in each of the individuals, it is possible to justify the lack of association in our results. Sharabi et al.21 found no difference in blood glucose levels, total cholesterol and triglyceride levels between the normoreactive and the hyperreactive groups.

The higher prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension observed in the elderly is well described in the literature.33 Although the mean age of the SRH subjects, at the time of undertaking ETT, did not allow us to classify them as elderly, this was significantly higher in this group than in the DRH and normoreactive groups. Thus, the effect of the age variable on the SBP during exercise is in accordance with the currently available information in the literature regarding the relationship between age and hypertension. The gradual loss of vessel elasticity and, the consequent reduction in vasodilatation capacity might explain our results. In this sense, Chang et al.3 showed that the vasodilatation extension was proportionally opposite to age and SBP variation.

Excess weight is related to an increase in PVR; thus, some research has shown a directly proportional relationship between weight gain and high BP.34 In the present study, it has been shown that the SRH group presented a BMI significantly higher than the normoreactive and DRH groups, which may justify per se the association between BMI and SRH. Widgren et al.35 reported that individuals with a family history of hypertension have a greater reactivity to physical and mental stress than those with none at all. Diwan et al.23 and Sharabi et al.21 reported that the number of individuals with EBPR was significantly greater in those who had hypertensive relatives compared with those who did not. It is possible that our results were biased, as information was collected directly with the participants of the cohort, therefore, relatives were not directly examined.

No studies have been found in the literature that have analyzed the association between genetic polymorphisms and EBPR. Some have reported the influence of determined genes during physical exercise;6 however, they have not specifically evaluated BP during exercise. It was decided to study the I/D ACE and M235T AGT polymorphisms owing to the current controversy in the literature with respect to the real relation between such polymorphisms and hypertension.7 In this study, no association was identified between the I/D polymorphisms of ACE and M235T of AGT with EBPR. However, it is possible that this association exists in populations where there is an association between these polymorphisms with hypertension, considering that EBPR is a pre-clinical stage of hypertension. There is a need to investigate this hypothesis in further studies.

In summary, only age and BMI independently influenced EBPR during ETT. If therefore age and BMI are risk factors for EBPR and if this is a risk marker for hypertension, then preventive strategies may be applied with greater emphasis to patients who present EBPR rather than those with normal BP during excercise, even though they present above-normal BMI and are more advanced in years. In other words, identifying the risk factors in individuals who have markers of the disease (pre-clinical stages) is of even greater importance, as they are individuals who have no overt signs of the disease, although they are actually in the process of developing the disease.

References

Miyai N, Arita M, Morioka I, Takeda S, Miyashita K . Ambulatory blood pressure, sympathetic activity, and left ventricular structure and function in middle-aged normotensive men with exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise. Med Sci Monit 2005; 11: 478–484.

Oliveira LB, Cunha AB, Martins WA, Abreu RFS, Barros LSN, Cunha DM, Nóbrega ACL, Martins-Filho LR . Monitorização ambulatorial da pressão arterial e pressão casual em hiperreatores ao esforço. Arq Bras Cardiol 2007; 88: 565–572.

Chang HJ, Chung J, Choi SY, Yoon MH, Hwang GS, Shin JH, Tahk SJ, Choi BI . Endothelial dysfunction in patients with exaggerated blood pressure response during treadmill test. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27: 421–425.

Shim CY, Ha JW, Park S, Choi EY, Choi D, Rim SJ, Chung N . Exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise is associated with augmented rise of angiotensin II during exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 287–292.

Jae SY, Fernhall B, Heffernan KS, Kang M, Lee MK, Choi YH, Hong KP, Ahn ES, Park WH . Exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise is associated with carotid atherosclerosis in apparently healthy men. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 881–887.

Oliveira EM, Alves GB, Barauna VG . Sistema renina-angiotensina: interação gene-exercício. Rev Bras Hipertens 2003; 10: 125–129.

Lima SG, Hatagima A, Silva NLCL . Sistema Renina-Angiotensina: é possível identificar genes de suscetibilidade à Hipertensão? Arq Bras Cardiol 2007; 89: 427–433.

Miyai N, Arita M, Morioka I, Miyashita K, Nishio I, Takeda S . Exercise BP response in subjects with high-normal BP: exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise and risk of future hypertension in subjects with high-normal blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 1626–1631.

Miyai N, Arita M, Miyashita K, Morioka I, Shiraishi T, Nishio I . Blood pressure response to heart rate during exercise test and risk of future hypertension. Hypertension 2002; 39: 761–766.

Andrade J . II DIRETRIZES da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia sobre teste Ergométrico. Arq Bras Cardiol 2002; 78 (Suppl 2): 1–17.

Myres J, Froelicher VF . Exercice testing: procedures and implementation. Cardiol Clin 1993; 11: 199–213.

Araújo MS, Menezes BS, Lourenço C, Cordeiro ER, Gatti RR, Goulart LR . O gene do angiotensinogênio (M235T) e o infarto agudo do miocárdio. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2005; 51: 164–169.

Alvarez R, Reguero JR, Batalla A, Iglesias-Cubero G, Cortina A, Alvarez V, Coto E . Angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin II receptor 1 polymorphism: association with early coronary disease. Cardiovascular Res 1998; 40: 375–379.

Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen JT . Anticipatory blood pressure response to exercise predicts future high blood pressure in middle-aged men. Hypertension 1996; 27: 1059–1064.

Marsaro EA, Vasquez EC, Lima EG . Avaliação da pressão arterial em indivíduos normais e hiperreatores. Um estudo comparativo dos métodos de medidas casual e da MAPA. Arq Bras Cardiol 1996; 67: 319–324.

Stewart KJ, Sung J, Silber HA, Fleg JL, Kelemen MD, Turner KL, Bacher AC, Dobrosielski DA, DeRegis JR, Shapiro EP, Ouyanq P . Exaggerated exercise blood pressure is related to impaired endothelial vasodilator function. Am J Hypertens 2004; 17: 314–320.

Tzemos N, Lim PO, MacDonald TM . Exercise blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Int J Clin Pract 2009; 63: 202–206.

Jae SY, Fernhall B, Lee M, Heffeman KS, Lee MK, Choi YH, Hong KP, Park WH . Exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise is associated with inflammatory markers. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2006; 26: 145–149.

Miyai N, Arita M, Miyashita K, Morioka I, Shiraishi T, Nishio I, Takeda S . Antihypertensive effects of aerobic exercise in middle-aged normotensive men with exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise. Hypertens Res 2002; 25: 507–514.

Bond V, Millis RM, Adams RG, Oke LM, Enweze L, Blakely R, Banks M, Thompson T, Obisesan T, Sween JC . Attenuation of exaggerated exercise blood pressure response in African-American women by regular aerobic physical activity. Ethn Dis 2005; 15 (Suppl 5): S5–13.

Sharabi Y, Ben-Cnaan R, Hanin A, Martonovitch G, Grossman E . The significance of hypertensive response to exercise as a predictor of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J Hum Hypertens 2001; 15: 353–356.

Rostrup M, Westheim A, Kjeldsen SE, Eide I . Cardiovascular reactivity coronary risk factors and sympathetic activity in young men. Hypertension 1993; 22: 891–899.

Diwan SK, Jaiswal N, Wanjari AK, Mahajan SN . Blood pressure response to treadmill testing among medical graduates: the right time to intervene. Indian Heart J 2005; 57: 237–240.

Morise AP . Heart rate recovery. Predictor of risk today and target of therapy tomorrow? Circulation 2004; 110: 2778–2780.

Vivekamamthan DP, Blackstone EH, Pothier CE, Lauer MS . Heart rate recovery after exercise is a predictor of mortality, independent of the angiographic severity of coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42: 831–838.

Hespanha R . Função Respiratória. In: Hespanha R (ed) Ergometria: Bases Fisiológicas e Metodologia Para a Prescrição de Exercício. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio, 2004, pp 53–70.

Takamura T, Onishi K, Sugimoto T, Kurita T, Fujimoto N, Dohi K, Tanigawa T, Isaka N, Nobori T, Ito M . Patients with a hypertensive response to exercise have impaired left ventricular diastolic function. Hypertens Res 2008; 31: 257–263.

Cipullo JP, Martin JFV, Ciorlia LAS, Godoy MRP, Cação JC, Loureiro AAC, Cesarino CB, Carvalho AC, Cordeiro JAC, Burdmann B . Prevalência e fatores de risco para hipertensão em uma população urbana brasileira. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010; 94: 519–526.

Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Polanczyk CA, Homrich CS, Rosa RS, Achutti AC . Fatores de risco para doenças não transmissíveis em área metropolitana na região sul do Brasil. Prevalências e simultaneidades. Rev Saúde Pública 1993; 27: 143–148.

Fuchs FD, Moreira LB, Moraes RS, Bredemeier M, Cardozo SC . Prevalência da hipertensão arterial sistêmica e fatores associados na região urbana de Porto Alegre. Estudo de base populacional. Arq Bras Cardiol 1994; 63: 473–479.

Gillum RF . Pathophysiology of hypertension in blacks and whites. A review of the basis of racial blood pressure differences. Hypertension 1979; 1: 468–475.

Klein CH, Silva NAS, Nogueira AR, Bloch KV, Campos LHS . Hipertensão arterial na Ilha do Governador, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. II. Prevalência. Cad Saúde Públ 1995; 11: 389–394.

Franklin SS . Hypertension in older people: part 1. J Clin Hypertens 2006; 8: 444–449.

Nadruz Jr W, Coelho OR . A inter-relação da hipertensão arterial com os outros fatores de risco cardiovascular. In: Brandão A (ed). Hipertensão. Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2006, pp 159–167.

Widgren BR, Wikstrand J, Berglund G, Andersson OK . Increased response to physical and mental stress in men with hypertensive parents. Hypertension 1992; 20: 606–611.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by FACEPE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Lima, S., de Albuquerque, M., de Oliveira, J. et al. Exaggerated blood pressure response during exercise treadmill testing: functional and hemodynamic features, and risk factors. Hypertens Res 35, 733–738 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.14

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Safety, efficacy and delivery of isometric resistance training as an adjunct therapy for blood pressure control: a modified Delphi study

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Increased mean arterial pressure response to dynamic exercise in normotensive subjects with multiple metabolic risk factors

Hypertension Research (2013)

-

Exercise stress testing as the significant clinical modality for management of hypertension

Hypertension Research (2012)