Abstract

A comparison is made of central aortic systolic pressure (CASP) and the radial augmentation index (rAIx) estimated with the B-Pro device and SphygmoCor (as reference) in 104 healthy Caucasians without drug treatment, together with an analysis of the relationship between CASP and rAIx, and arterial stiffness. Peripheral and central blood pressure, and the rAIx were measured with B-pro and SphygmoCor, with determination of the central augmentation index (CAIx), pulse wave velocity (PWV), carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) and the ankle-brachial index (ABI). rAIx as determined with B-Pro was greater than measured with SphygmoCor (5.85; 95%CI: 1.75–9.96), in the same way as CASP, estimated from the transfer function (1.47; 95%CI: 0.47–2.47 mm Hg) and with the second peak of the radial wave (4.46; 95%CI: 2.80–6.12 mm Hg). The Pearson correlation coefficient for CASP with B-Pro and SphygmoCor was r=0.937 (P<0.01), with an intraclass correlation of 0.972 (95%CI: 0.959–0.981). In the case of rAIx, the correlation coefficient was r=0.436 (P<0.01), with an intraclass correlation of 0.599 (95% CI: 0.409–0.728). The correlation of CASP (B-pro) with PWV was r=0.558 (P<0.01), with CAIx r=0.253 (P<0.01) and with carotid IMT r=0.442 (P<0.01). The correlation of rAIx (B-Pro) with age was r=0.369 (r<0.01), and with CAIx r=0.463 (P<0.001). Central arterial pressure estimated with B-Pro in healthy Caucasians without drug treatment offers adequate validity vs. the reference standard (SphygmoCor). However, in the estimation of rAIx, some differences with respect to the reference standard have been detected, probably related to measurement of the second peak of the radial wave.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The relationship between clinical and ambulatory peripheral arterial pressures, and cardiovascular morbidity-mortality and target organ damage has been well established.1, 2, 3, 4 However, there is growing evidence that central aortic arterial pressure may be better than peripheral arterial pressure in predicting cardiovascular events.5, 6, 7

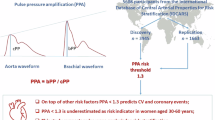

The gold standard for assessing central arterial pressure is direct measurement with an intra-aortic transducer. However, the technical difficulties of this technique preclude its use in clinical practice. A number of methods and devices are currently available for estimating central aortic systolic pressure (CASP), either directly from the second peak systolic blood pressure (SBP) corresponding to the radial pulse wave (SBP2) or using a mathematical transfer function that estimates CASP.8, 9, 10 The reference device for estimating these measures is the SphygmoCor system (pulse wave analysis).7, 11

Recently, a new system has been developed that estimates derived aortic pressure using an n-point moving average method (B-Pro device® + A-pulse software).12 This device has been validated in some sub-populations, particularly in the high-risk hypertensive individuals and in the Asian populations, but it has not been validated to date in healthy Caucasians without drug treatment. The morphology of the radial pulse can also be used to estimate the peripheral or radial augmentation index (rAIx), as a parameter assessing vascular structure and function.13, 14 However, few studies have been made of the relationships with other arterial stiffness parameters, or of comparisons between different methods that estimate this same parameter.

The present study compares CASP and the rAIx estimated with the B-Pro device and SphygmoCor (as reference) in healthy Caucasians without drug treatment, and analyzes the relationship between CASP and rAIx and other parameters that assess vascular structure and function.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was carried out to evaluate the association of lifestyles with the circadian pattern of blood pressure, arterial stiffness and endothelial function in a previously established cohort of healthy subjects with different levels of physical activity. The protocol of the EVIDENT study (NCT01083082) has been previously published.15

Subjects

Study population

Subjects aged 20–80 years were selected from the PEPAF project cohort.16 The exclusion criteria were: known coronary or cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease, heart failure, moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, walking-limiting musculoskeletal disease, advanced respiratory, renal or liver disease, severe mental diseases, treated oncological disease diagnosed in the past 5 years, pregnant women and terminal patients.

Sample size calculation indicated that the 104 patients included in the study were sufficient to detect a 2-mm Hg difference in CASP between the two devices, with a standard deviation difference of 5.15 mm Hg, a significance level of 95%, and a power of 97.5% (Epidat 4.0; PAHO/WHO). We selected the first 104 healthy patients without cardiovascular disease, diabetes or hypertension, and without hypertensive or diabetes drugs. The study was approved by an independent ethics committee of Salamanca University Hospital (Spain), and all participants gave written informed consent according to the general recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki.17

Measurement

A trained nurse research performed all measures except carotid intima media thickness (IMT). A detailed description has been published elsewhere of how the clinical data were collected, how the anthropometric measurements were made, and how the analytical parameters were obtained.15

Office or clinical blood pressure

Office blood pressure measurement involves three measurements of SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), using the average of the last two, with a validated OMRON model M7 sphygmomanometer (Omron Health Care, Kyoto, Japan), and following the recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension.18 Pulse pressure (PP) was estimated from the mean values of the second and third measurements.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was performed on a day of standard activity, with a radial tonometer. A radial pulse wave acquisition device (B-Pro®; HealthSTATS International, Singapore, Singapore), validated according to the protocol of the European Society of Hypertension, the Association for Advancement of Medical Instrumentation and the British Hypertension Society19 was used. The registries in which the percentage of valid readings was ⩾80% of the total and with valid readings at all times were considered to be valid. The monitor was scheduled for obtaining blood pressure measurements every 15 min during the daytime and rest period. The average and dispersion estimators of SBP and DBP were calculated during the 24-h, daytime and night-time periods, defined on the basis of the diary reported by the patient. The patients were classified according to circadian pattern estimated from the SBP night/day ratio as dipper <0.9, non-dipper 0.9–1 and riser >1.

Central blood pressure and peripheral augmentation index

Central blood pressure was measured with Pulse Wave Application Software (B-Pro+A-Pulse software; HealthSTATS International) using tonometry attached to a wrist (like a wristwatch) to record the radial pulse with the patient in the sitting position and resting the arm on a firm surface, using an equation to estimate CASP.12 The increases in central blood pressure, mean blood pressure and rAIx were estimated as well. rAIx was calculated from the radial wave pulse as follows: (second peak SBP (SBP2)−DBP)/(first peak SBP−DBP) × 100,13 as seen in Figure 1. Intra-observer reliability evaluated in 20 subjects before the study began, using the intraclass correlation coefficient, showed values of 0.971 (95%CI: 0.923–0.989) for CASP and 0.952 (95%CI: 0.871–0.982) for rAIx. Bland–Altman analysis in turn yielded a limit of agreement of −0.056 (95%CI: −9.41 to 9.30) for CASP and 2.50 (95%CI: −14.43 and 19.46) for rAIx.

Pulse wave velocity (PWV) and peripheral (PAIx) and central (CAIx) augmentation index were estimated with the SphygmoCor (AtCor Medical Pty Ltd., Head Office, West Ryde, Australia). Using the SphygmoCor (Px Pulse Wave Analysis) with the patient in the sitting position and resting the arm on a firm surface, pulse wave analysis was performed with a sensor in the radial artery connected to a desktop device, using mathematical transformation to estimate the aortic pulse wave. The reliability of the measure was evaluated before the study began using the intraclass correlation coefficient, which showed values of 0.979 (95%CI: 0.948–0.992) for intra-observer agreement on repeated measurements in 20 subjects, while Bland–Altman analysis yielded a limit of intra-observer agreement of 0.650 (95%CI: −6.496 to 7.796). From the morphology of the aortic wave, central AIx was estimated using the following formula: increase in central pressure × 100/PP. rAIx in turn was calculated from the radial wave pulse as follows: (second peak SBP (SBP2)−DBP)/(first peak SBP−DBP) × 100.13 Using the SphygmoCor (PWV), and with the patient in the supine position, the pulse wave of the carotid and femoral arteries was analyzed, estimating the delay with respect to the electrocardiogram wave and calculating the PWV. Distance measurements were taken with a measuring tape from the sternal notch to the carotid and femoral arteries at the sensor location. The quality of measurement was ⩾80% in all cases, with a mean of 89.01±6.15. The measurements of peripheral and central blood pressure with B-Pro and SphygmoCor were obtained one after the other, and in no case exceeding a duration of 1 h from the start of the first step to the end of the second.

Assessment of carotid IMT

Carotid ultrasonography to assess IMT was performed by two investigators trained for this purpose before starting the study. Reliability was evaluated before the study began, using the intraclass correlation coefficient, which showed values of 0.974 (95%CI: 0.935–0.990) for intra-observer agreement on repeated measurements in 20 subjects, and 0.897 (95%CI: 0.740–0.959) for inter-observer agreement—Bland–Altman analysis yielding a limit of inter-observer agreement of 0.022 (95%CI: −0.053 to 0.098), with a limit of intra-observer agreement of 0.012 (95%CI: −0.034 to 0.059). A Sonosite Micromax ultrasound device (SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) paired with a 5–10-MHz multifrequency high-resolution linear transducer using Sonocal software was employed for automatic measurements of IMT, in order to optimize reproducibility. Measurements were made of the common carotid after the examination of a longitudinal section of 10 mm at a distance of 1-cm from the bifurcation, performing measurements in the anterior or proximal wall, and in the posterior or distal wall in the lateral, anterior and posterior projections, following an axis perpendicular to the artery to discriminate two lines: one for the intima-blood interface and the other for the media-adventitious interface. A total of six measurements were obtained of the right carotid and another six of the left carotid, using average values (average IMT) and maximum values (maximum IMT) calculated automatically by the software. The measurements were obtained with the subject lying down, and the head extended and slightly turned opposite to the examined carotid, following the recommendations of the Manheim Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Consensus.20

Evaluation of peripheral artery involvement was based on the ankle-brachial index (ABI), recorded in the morning without having consumed coffee or tobacco for at least 8 h before measurement, and with a room temperature of 22–24 °C. With the feet uncovered, in supine decubitus after 20 min of rest, the pressure in the lower extremities and blood pressure in both arms were measured using a portable WatchBP Office ABI (Microlife AG Swiss Corporation, Widnau, Switzerland). ABI was automatically calculated for each foot by dividing the higher of the two systolic pressures in the ankle by the highest measurement of the two systolic pressures in the arm.21

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation, while frequency distributions were used in the case of qualitative variables. The paired Student t-test was used to compare blood pressure measurements between the two instruments used. MANOVA test was used to adjust for age, sex and heart rate. Pearson's correlation coefficient and intraclass correlation coefficients were used to estimate the relationships between quantitative variables. Additional comparisons were based on simple linear regression and Bland–Altman plots. We performed a multiple linear regression analysis taking as dependent variables rAIx estimated with B-pro and SphygmoCor. A first step with the ‘enter’ method was used to include adjusted variables: age, sex and office heart rate, followed by a second step with the ‘stepwise’ method to include independent variables: smoking, waist circumference, body mass index, office SBP, office DBP, percentage dipping, PWV and carotid IMT. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 18.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 50.44 (s.d. 11.02) years, and 68.30% were women. Fourteen subjects were under 40 years of age (64.29% women), 70 were between 40–60 years of age (68.57% women), and 20 were over 50 years of age (70% women). Clinical and ambulatory blood pressures, as well as the mean laboratory test values, were within normal ranges. The evaluated arterial stiffness parameters were also normal, with a PWV of 6.92 m s−1, central augmentation index (CAIx) 30.97%, carotid IMT 0.64 mm and ABI 1.17. The peripheral and central arterial pressures, and rAIx evaluated with the B-Pro and SphygmoCor are reported in Table 2. Peripheral SBP determined with B-Pro proved slightly greater than with SphygmoCor (P<0.05), whereas DBP was similar (P>0.05), and the mean arterial pressure was lower (P<0.05). CASP was greater with B-Pro, estimated both from the transfer function (1.47; 95%CI: 0.47–2.47 mm Hg) and from the second peak of the radial wave (4.46; 95%CI: 2.80–6.12 mm Hg). rAIx as determined with B-pro was also greater than measured with SphygmoCor (5.85 points; 95%CI: 1.75–9.96). The Pearson correlation coefficient corresponding to the difference between SBP2 and rAIx was 0.752 (P<0.01).

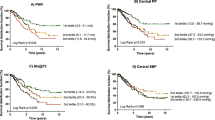

The Pearson correlation coefficients of the peripheral and central arterial pressures determined with B-Pro and SphygmoCor were very high, with r=0.949 (P<0.01) for central arterial pressure, and an intraclass correlation of 0.972 (95%CI: 0.959–0.981; Figure 2). The Bland–Altman plot (Figure 2) showed a limit of agreement of 1.47 (s.d. 5.15). The correlation for rAIx was lower (r=0.436), with an intraclass correlation of 0.599 (95%CI: 0.409–0.728), and a limit of agreement in the Bland-ltman plot of 5.85 (s.d. 21.09; Figure 2).

Simple linear regression and Bland–Altman plots of central aortic systolic pressure (CASP) and radial augmentation index (rAIx) estimated with the B-Pro device and the SphygmoCor system. Equation of the line: CASP (B-Pro)=13.932+0.882 × CASP(Sphig). R2=0.900; r=0.949. Intraclass correlation coefficient of CASP: r=0.972 (95%CI 0.959 to 0.981) P<0.001. Mean difference in Bland–Altman analysis 1.47 (s.d. 5.15). Equation of the line: rAIx(Bpro)=47.709+0.534 × rAIx(Sphig). R2=0.190; r=0.436. Intraclass correlation coefficient of rAIx:r=0.599 (95%CI: 0.409–0.728), P<0.001. Mean difference in Bland–Altman analysis 5.85 (s.d. 21.09).

The correlations of the other B-pro and SphygmoCor measures were: peripheral SBP r=0.983, peripheral DBP r=0.929, peripheral MBP r=0.950, SBP2 r=0.893, central aortic DBP r=0.929 and central PP r=0.798 (P<0.01). Table 3 shows the correlations of the measures of peripheral and central arterial pressure and rAIx obtained with SphygmoCor and B-Pro, and the measures of arterial stiffness. A moderate-high correlation was found for central arterial pressure (B-Pro) and PWV (r=0.558, P<0.01), CAIx (r=0.253, P<0.05), mean IMT (r=0.442, P<0.01) and 24-h PP (r=0.680, P<0.01)—with no relation to either ABI or the systolic arterial pressure night/day ratio. The correlation of rAIx (B-Pro) to age was r=0.369 (r<0.01), vs. r=0.463 (P<0.01) to CAIx and r=0.227 (P<0.05) to 24-h PP. rAIx estimated with SphygmoCor showed an inverse correlation to CAIx (r=0.871, P<0.01), IMT (r=0.259, P<0.01), PWV (r=0.214, P<0.01) and age (r=0.499, P<0.01).

Lastly, in the multiple regression analysis of rAIx estimated with B-Pro (Table 4) as dependent variable, after adjusting for age, sex and clinical heart rate, only DBP remained in the equation—though age and sex also reached statistical significance. On considering rAIx estimated with SphygmoCor as dependent variable, body mass index was seen to be retained in the equation, along with all the aforementioned variables.

Discussion

A strong correlation (Pearson) and intraclass correlation was found between CASP estimated with B-Pro and with the reference technique (SphygmoCor) in healthy Caucasians without drug treatment. CASP was also positively correlated to parameters evaluating vascular structure and function, such as PWV, CAIx and carotid IMT. However, the correlation between rAIx with the two methods was of lesser magnitude, and with the value estimated using B-Pro no relationship to the parameters assessing vascular structure and function was found (with the exception of CAIx), whereas in contrast the value estimated with SphygmoCor showed a greater correlation to CAIx and also a positive correlation to IMT and PWV.

CASP estimated directly with the transfer function was slightly higher with B-Pro, and although the result was statistically significant, it did not seem to be clinically relevant (1.47; 95%CI: 0.47–2.47 mm Hg). However, the differences found on estimating SBP2 were greater, and could be of clinical relevance (4.46; 95%CI: 2.80–6.12 mm Hg). In addition, the differences in rAIx could be explained based on the high correlation between the differences of these parameters with the two methods used. The difference in heart rate may be one of the reasons why measurement with B-Pro is slightly higher than with SphygmoCor, probably because the patient is more relaxed due to the fact that this measure was obtained after recording with B-Pro. To this we may add the slight underestimation of CASP with SphygmoCor vs. the invasive method, as has already been reported by other authors22, 23—a situation that does not appear to occur with B-Pro.12 Williams et al.12 reported similar results, though of lesser magnitude. The CASP values obtained with B-Pro were 0.33 mm Hg higher (95%CI: 0.30–0.36) when estimated with the transfer function, and 1.57 mm Hg higher (95%CI: 1.49–1.65) when estimated with SBP2, vs. the values determined with SphygmoCor.

The correlation found between the two measurements of CASP (r=0.94, P<0.01) was also similar to that reported by Williams et al., depending on the method employed (r=0.95 or r=0.99). However, the intraclass correlation in this study was intermediate between the two (r=0.97, 95%CI: 0.96–0.98)—thus indicating that the measures may be inter-exchangeable. The relationships between CASP estimated with B-Pro and other dependent variables indicating alterations in vascular structure and function appear adequate—exhibiting a positive correlation with age, PWV, carotid IMT and PP both in central arterial pressure estimated from the transfer function and with SBP2, in the same way as the estimation with SphygmoCor. The correlation with PWV (r=0.56, P<0.05), as the gold standard for assessing arterial stiffness,24 and with carotid IMT-greater (r=0.44, P<0.01) than reported by Wang et al.6 (r=0.25, P<0.01)-confirms validity in assessing vascular structure and function.

Regarding rAIx, a difference is observed between the two methods—the estimation with B-Pro being 5.85% greater (95%CI: 1.75–9.96)—and the correlation of both indexes proved moderate (r=0.436, P<0.01). The observed correlation between rAIx and age (r=0.37 with B-Pro and 0.50 with SphygmoCor) is lower than that reported by Kohara et al.14 in a group of healthy volunteers (r=0.62 in males and r=0.64 in females). These authors also found a positive correlation (r=0.82, P<0.001) between CAIx estimated with SphygmoCor and rAIx estimated with HEM-9010AI, similar to that seen in our study with SphygmoCor (r=0.86, P<0.01) but greater than that found between CAIx estimated with SphygmoCor, and rAIx estimated with B-Pro (r=0.46, P<0.01). The rAIx values reported by both Kohara et al.14 (0.69±16.3 in males and 0.81±16.1 in females) and Munir et al.13 (0.79±11.8) are lower than those obtained in our study. However, considering that the correlation of our data using SphygmoCor coincides with the results of other authors13, 14 and is in disagreement with the estimation of rAIx using B-Pro, it would seem necessary to revise the methodology used by this device in estimating this parameter. Probably, as already mentioned, the difference found in estimating the second peak of the systolic pressure is one of the reasons for this discrepancy. This point is not a ‘peak’, as stated, but a special point at which dP/dt changes sharply. As a result, a shift in the arrival time of the reflected wave is translated into changes in the SBP2. However, the behavior of both parameters in the multiple regression equation is similar with age and DBP as principal determinants of rAIx, to which body mass index is moreover added in the determination using SphygmoCor. It could be considered that rAIx increases by 0.61 units (95%CI: 0.16–0.89) with every year of increase in age. No relationship was found between rAIx determined with B-Pro and any of the arterial stiffness parameters except CAIx. However, rAIx estimated with SphygmoCor showed a correlation to IMT (r=0.260, P<0.01) and PWV (r=0.21, P<0.01). In turn, Sugawara et al.,25 in a study of 204 apparently healthy individuals, also observed a positive correlation of rAIx with aortic PWV (r=0.47, P<0.01), though this relationship was not retained in the multiple regression analysis. The intraclass correlation between the two methods is also relatively low (r=0.60, 95%CI: 0.41–0.73), with a wide limit of agreement in the Bland–Altman plot (mean difference 5.85, s.d. 21.09). This suggests reliability and validity problems. In any case, as has been reported elsewhere,26, 27 it must be remembered that the association between PWV and other arterial stiffness parameters behaves differently depending on the patient disease; as a result, the measures are not inter-exchangeable in clinical practice.

As a main limitation to our study, the reference standard used was not an invasive method but the SphygmoCor, which has already been validated vs. invasive techniques, and is known to slightly underestimate CASP depending on the calibration method used.28, 29 Measurement with both devices moreover was not carried out simultaneously but consecutively (first with B-Pro and then with SphygmoCor)—the time between the start of the first measurement and the end of the second in no case exceeding 1 h.

Furthermore, the number of patients was not very large, and all were healthy, without antihypertensive or antidiabetic drug treatments. The results therefore cannot be generalized to the hypertensive or diabetic individuals, or to the patients with cardiovascular diseases subjected to drug treatment—though they can be extended to the rest of the population without these diseases and who do not take drugs of this kind.

Conclusions

Central arterial pressure estimated with B-Pro in healthy Caucasians without drug treatment offers adequate validity vs. the reference standard (SphygmoCor), and thanks to its easy use could be employed for estimating this parameter in clinical practice. However, in the estimation of rAIx some differences with respect to the reference standard have been detected, probably related to measurement of the second peak of the radial wave, and which could reduce its validity in application to routine clinical practice. The association of CASP to the parameters that measure vascular structure and function (PWV, IMT and central AIx) was moderate. However, the relationship between rAIx and these parameters was zero or small—though a correlation was observed with central AIx.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Dolan E, Stanton A, Thijs L, Hinedi K, Atkins N, McClory S, Den Hond E, McCormack P, Staessen JA, O'Brien E . Superiority of ambulatory over clinic blood pressure measurement in predicting mortality: the Dublin outcome study. Hypertension 2005; 46: 156–161.

Czernichow S, Zanchetti A, Turnbull F, Barzi F, Ninomiya T, Kengne AP, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Perkovic V, Huxley R, Arima H, Patel A, Chalmers J, Woodward M, MacMahon S, Neal B . The effects of blood pressure reduction and of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events according to baseline blood pressure: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 4–16.

Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Law MR, Elliott P, MacMahon S, Rodgers A . Blood pressure and the global burden of disease 2000. Part II: estimates of attributable burden. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 423–430.

Matsui Y, Ishikawa J, Eguchi K, Shibasaki S, Shimada K, Kario K . Maximum value of home blood pressure: a novel indicator of target organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension 2011; 57: 1087–1093.

Huang CM, Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Sung SH, Yu WC, Ting CT, Lakatta EG, Yin FC, Chou P, Chen CH . Central versus ambulatory blood pressure in the prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 454–459.

Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Spurgeon HA, Ting CT, Lakatta EG, Yin FC, Chou P, Chen CH . Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens 2009; 27: 461–467.

Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, Cruickshank K, Stanton A, Collier D, Hughes AD, Thurston H, O′Rourke M . Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation 2006; 113: 1213–1225.

Chen CH, Nevo E, Fetics B, Pak PH, Yin FC, Maughan WL, Kass DA . Estimation of central aortic pressure waveform by mathematical transformation of radial tonometry pressure. Validation of generalized transfer function. Circulation 1997; 95: 1827–1836.

Hope SA, Meredith IT, Tay D, Cameron JD . ‘Generalizability’ of a radial-aortic transfer function for the derivation of central aortic waveform parameters. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1812–1820.

Cheng HM, Wang KL, Chen YH, Lin SJ, Chen LC, Sung SH, Ding PY, Yu WC, Chen JW, Chen CH . Estimation of central systolic blood pressure using an oscillometric blood pressure monitor. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 592–599.

Pauca AL, O′Rourke MF, Kon ND . Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension 2001; 38: 932–937.

Williams B, Lacy PS, Yan P, Hwee CN, Liang C, Ting CM . Development and validation of a novel method to derive central aortic systolic pressure from the radial pressure waveform using an N-point moving average method. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 951–961.

Munir S, Guilcher A, Kamalesh T, Clapp B, Redwood S, Marber M, Chowienczyk P . Peripheral augmentation index defines the relationship between central and peripheral pulse pressure. Hypertension 2008; 51: 112–118.

Kohara K, Tabara Y, Oshiumi A, Miyawaki Y, Kobayashi T, Miki T . Radial augmentation index: a useful and easily obtainable parameter for vascular aging. Am J Hypertens 2005; 18 (Pt 2): 11S–14S.

Garcia-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Martin-Cantera C, Cabrejas-Sanchez A, Gomez-Arranz A, Gonzalez-Viejo N, Iturregui-San Nicolas E, Patino-Alonso MC, Gomez-Marcos MA . Physical exercise, fitness and dietary pattern and their relationship with circadian blood pressure pattern, augmentation index and endothelial dysfunction biological markers: EVIDENT study protocol. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 233.

Grandes G, Sanchez A, Torcal J, Sanchez-Pinilla RO, Lizarraga K, Serra J . Targeting physical activity promotion in general practice: characteristics of inactive patients and willingness to change. BMC Public Health 2008; 8: 172.

World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997; 277: 925–926.

O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Padfield P, Palatini P, Parati G, Pickering T, Redon J, Staessen J, Stergiou G, Verdecchia P . Practice guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension for clinic, ambulatory and self blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens 2005; 23: 697–701.

Nair D, Tan SY, Gan HW, Lim SF, Tan J, Zhu M, Gao H, Chua NH, Peh WL, Mak KH . The use of ambulatory tonometric radial arterial wave capture to measure ambulatory blood pressure: the validation of a novel wrist-bound device in adults. J Hum Hypertens 2008; 22: 220–222.

Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Fatar M, Hernandez Hernandez R, Jaff M, Kownator S, Prati P, Rundek T, Sitzer M, Schminke U, Tardif JC, Taylor A, Vicaut E, Woo KS, Zannad F, Zureik M . Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness consensus (2004–2006). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd and 4th Watching the Risk Symposium, 13th and 15th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, and Brussels, Belgium, 2006. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007; 23: 75–80.

Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WR, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor Jr LM, White CJ, White J, White RA, Antman EM, Smith Jr SC, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gibbons RJ, Hunt SA, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B . ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006; 113: e463–e654.

Cloud GC, Rajkumar C, Kooner J, Cooke J, Bulpitt CJ . Estimation of central aortic pressure by SphygmoCor requires intra-arterial peripheral pressures. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003; 105: 219–225.

Davies JI, Band MM, Pringle S, Ogston S, Struthers AD . Peripheral blood pressure measurement is as good as applanation tonometry at predicting ascending aortic blood pressure. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 571–576.

Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H . Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 2588–2605.

Sugawara J, Komine H, Hayashi K, Maeda S, Matsuda M . Relationship between augmentation index obtained from carotid and radial artery pressure waveforms. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 375–381.

Gomez-Marcos MA, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Patino-Alonso MC, Agudo-Conde C, Gomez-Sanchez L, Rodriguez-Sanchez E, Martin-Cantera C, Garcia-Ortiz L . Relationship between intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery and arterial stiffness in subjects with and without type 2 diabetes: a case-series report. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2011; 10: 3.

Jerrard-Dunne P, Mahmud A, Feely J . Ambulatory arterial stiffness index, pulse wave velocity and augmentation index--interchangeable or mutually exclusive measures? J Hypertens 2008; 26: 529–534.

Hope SA, Meredith IT, Cameron JD . Effect of non-invasive calibration of radial waveforms on error in transfer-function-derived central aortic waveform characteristics. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004; 107: 205–211.

Verbeke F, Segers P, Heireman S, Vanholder R, Verdonck P, Van Bortel LM . Noninvasive assessment of local pulse pressure: importance of brachial-to-radial pressure amplification. Hypertension 2005; 46: 244–248.

Acknowledgements

This project has been supported by the Carlos III Institute of Health of the Spanish Ministry of Health (FIS: PS09/00233, PS09/01057, PS09/01972, PS09/01376, PS09/0164, PS09/01458, RETICS D06/0018) and the Health Service of Castilla y León (SAN/1778/2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Members of the EVIDENT group:

Coordinating centre: Luis Garcia Ortiz, Manuel A Gómez Marcos and José I Recio Rodriguez and Carmen Patino Alonso of the Primary Care Research Unit of La Alamedilla health centre, Salamanca. Spain.

Health centres:

La Alamedilla Health centre: Castilla y León Health Service–SACYL, Salamanca, Spain. Carmen Castaño Sanchez, Carmela Rodriguez Martín, Yolanda Castaño Sanchez, Cristina Agudo Conde, Emiliano Rodriguez Sanchez, Luis J Gonzalez Elena, Carmen Herrero Rodriguez, Benigna Sanchez Salgado, Angela de Cabo Laso and Jose A Maderuelo Fernandez.

Passeig de Sant Joan Health centre: Catalan Health Service–CS, Barcelona, Spain. Carlos Martín Cantera. Joan Canales Reina, Epifania Rodrigo de Pablo, Maria Lourdes Lasaosa Medina, Maria Jose Calvo Aponte, Amalia Rodriguez Franco, Elena Briones Carrio, Carme Martin Borras, Anna Puig Ribera and Ruben Colominas Garrido.

Poble Sec Health centre: Catalan Health Service –CS, Barcelona, Spain. Ma Teresa Vidal Sarmiento, Ángela Viaplana Serra, Susanna Bermúdez Chillida, Aida Tanasa, Guillem Fluxà Terrasa, Montserrat Caubet Gomà, Carolina Galindo Parres, Juan José Antón Álvarez and Prudencia Toribio Medina.

Ca N'Oriac Health centre: Catalan Health Service –CS, Sabadell-Barcelona, Spain. Montserrat Romaguera Bosch, Amanda Cid Cantarero Juan J Sechuran Asca, Josep Sanz López, Carme Berbel Navarro, Marta Serra Laguarta, Pilar Polo Berdiez, Juan A Garcia Quintana, Olga Argüello Moreno, Elena de Prado Peña and Dolores Moreno Andújar.

Sant Roc Health centre: Catalan Health Service—CS, Barcelona, Spain. Maria Mar Domingo, Anna Girona, Nuria Curos, Francisco Javier Mezquiriz, Laura Torrent.

Cuenca III Health centre: Castilla-La Mancha Health Service–SESCAM, Cuenca, Spain. Alfredo Cabrejas Sánchez, María Teresa Pérez Rodríguez, María Luz García García, Jorge Lema Bartolomé and Fernando Salcedo Aguilar.

Casa de Barco Health centre: Castilla y León Health Service–SACYL,Valladolid, Spain. Carmen Fernandez Alonso, Amparo Gómez Arranz, Elisa, Ibáñez Jalón, Aventina de la Cal de la Fuente, Laura Muñoz Beneitez, Natalia Gutiérrez, Ruperto Sanz Cantalapiedra, Luis M Quintero Gonzalez, Sara de Francisco Velasco, Miguel Angel Diez Garcia, Eva Sierra Quintana and Maria Cáceres.

Torre Ramona Health centre: Aragón Health Service—Salud, Zaragoza, Spain. Natividad González Viejo, José Felix Magdalena Belio, Luis Otegui Ilarduya, Francisco Javier Rubio Galán, Amor Melguizo Bejar, Cristina Inés Sauras Yera, Ma Jesus Gil Train, Marta Iribarne Ferrer and Miguel Angel Lafuente Ripolles.

Primary Care Research Unit of Bizkaia: Basque Health Service-Osakidetza, Bilbao, Spain. Gonzalo Grandes, Alvaro Sanchez, Imanol Montoya, Eguskiñe Iturregui San Nicolás, Paloma Escondrillas Wencell, Javier Rodriguez Morua, Amaia Martín and Nahia Guenaga.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia-Ortiz, L., Recio-Rodríguez, J., Canales-Reina, J. et al. Comparison of two measuring instruments, B-pro and SphygmoCor system as reference, to evaluate central systolic blood pressure and radial augmentation index. Hypertens Res 35, 617–623 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ambulatory monitoring of central arterial pressure, wave reflections, and arterial stiffness in patients at cardiovascular risk

Journal of Human Hypertension (2022)

-

Combined use of a healthy lifestyle smartphone application and usual primary care counseling to improve arterial stiffness, blood pressure and wave reflections: a Randomized Controlled Trial (EVIDENT II Study)

Hypertension Research (2019)

-

Comparison of non-invasive blood pressure monitoring using modified arterial applanation tonometry with intra-arterial measurement

Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing (2018)

-

Twenty-Four-Hour Ambulatory Pulse Wave Analysis in Hypertension Management: Current Evidence and Perspectives

Current Hypertension Reports (2016)

-

Electrocardiogram derived QRS duration associations with elevated central aortic systolic pressure (CASP) in a rural Australian population

Clinical Hypertension (2015)