Abstract

Previous clinical and experimental studies have indicated that magnesium may prevent vascular calcification (VC), but mechanistic characterization has not been reported. This study investigated the influence of increasing magnesium concentrations on VC in a rat aortic tissue culture model. Aortic segments from male Sprague-Dawley rats were incubated in serum-supplemented high-phosphate medium for 10 days. The magnesium concentration in this medium was increased to demonstrate its role in preventing VC, which was assessed by imaging and spectroscopy. The mineral composition of the calcification was analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic imaging, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping. Magnesium supplementation of high-phosphate medium dose-dependently suppressed VC (quantified as aortic calcium content), and almost ablated it at 2.4 mm magnesium. The FTIR images and SEM–EDX maps indicated that the distribution of phosphate (as hydroxyapatite), phosphorus and Mg corresponded with calcium content in the aortic ring and VC. The inhibitory effect of magnesium supplementation on VC was partially reduced by 2-aminoethoxy-diphenylborate, an inhibitor of TRPM7. Furthermore, phosphate transporter-1 (Pit-1) protein expression was increased in tissues cultured in HP medium and was gradually—and dose dependently—decreased by magnesium. We conclude that a mechanism involving TRPM7 and Pit-1 underpins the magnesium-mediated reversal of high-phosphate-associated VC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vascular calcification (VC) is prevalent in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and leads to an increase in cardiovascular disease and both overall and cardiovascular mortality rates.1, 2, 3, 4 Phosphate concentrations at supra-physiological levels are considered the most effective inducer of VC in experimental in vivo and in vitro models. We previously reported that increased uptake of phosphate through phosphate transporter-1 (Pit-1)-induced calcification of VSMCs in an aortic tissue culture model.5, 6

Magnesium is the fourth most abundant mineral cation in the body and plays an important role in numerous enzyme reactions, transport processes and synthetic systems (for example, for proteins, DNA and RNA). Recent studies—in the general population, predialysis CKD patients, and hemodialysis patients—have shown low magnesium levels to correlate with both overall and cardiovascular mortality.7, 8, 9 In middle-aged subjects, 24-h urine magnesium was inversely associated with cardiovascular risk factors.10

The link between serum magnesium and VC has been assessed in several clinical studies. A prospective study in 47 hemodialysis patients revealed an association between serum magnesium and intima-media thickness in carotid arteries, and that CKD patients with higher serum magnesium had a significantly lower pulse wave velocity (PWV).11 Furthermore, an observational study in 283 CKD patients reported an association between high serum magnesium and improved endothelial function.12 We previously reported the significance of serum magnesium as an independent factor modulating parathyroid hormone levels in 1231 uremic patients.13

In vivo animal studies have shown dietary magnesium or magnesium-containing phosphate binders prevent VC.14 In vitro studies confirm the preventive effect of magnesium on VC,15, 16 with high magnesium levels being shown to prevent calcification of bovine vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)17 and in human aortic VSMCs.18 However, the mechanisms by which magnesium may influence VC remain unclear. The present study aimed to investigate, in an aortic tissue culture model, whether increasing magnesium affects VC, and whether Transient Receptor Potential Melastin 7 (TRPM7) and Pit-1 are mechanistically implicated in this effect. We also elucidated the mineral composition of the vascular calcification using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic imaging, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (7 weeks old; Kiwa Laboratory Animals Co., Wakayama, Japan) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle. After 2–7 days of acclimatization, all rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal administration of 100 mg kg−1 of pentobarbital and their aortas recovered for culture. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Wakayama Medical University, and were in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Aortic tissue culture

Aortic tissue culture was performed as previously described.6 Briefly, aortas (from the arch to the iliac bifurcation) were removed and carefully denuded of connective tissue. The vessels were cut into 3–5-mm rings and placed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin and streptomycin. Aortic segments were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator, changing the medium every 2 days for a total of 10 days. The concentrations of Ca2+ and phosphate in the DMEM were 1.8 and 0.9 mm, respectively, with a pH of 7.2 (control). To stimulate phosphate-induced calcification, NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4 were added to serum-supplemented DMEM to give a final phosphate concentration of 3.8 mM. MgSO4 was added to this high-phosphate medium to create various magnesium concentrations. To investigate the role of TRPM7—a Mg2+ transporter—we applied 200 μmol l−1 2-aminoethoxy-diphenylborate (2-APB) to inhibit TRPM7.

On completion of the 10-day culture, aortic segments were washed twice in calcium–magnesium-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) and divided into four analysis groups. Group 1 was weighed on a microbalance and retained for the measurement of calcium content. Group 2 was mounted in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, CA, USA) and sliced into 4 μm cryosections for microspectroscopy analysis. Group 3 was mixed with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for extraction of total RNA (tRNA), and Group 4 was homogenized in RIPA buffer (#9806, Cell Signaling Technology Japan, Tokyo, Japan) for western blot analysis.

Quantification of calcification

Aortic segments were weighed and decalcified with 10% formic acid for 24 h. The calcium content of the supernatant was quantified by the methylxylenol blue method using the Wako Calcium E-Test (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Results were corrected by wet tissue weight and expressed as mg g−1 wet weight of tissue.

FTIR imaging

FTIR images were acquired using an imaging system with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) line detector comprising 16 pixel elements (Spotlight 400/Spectrum 400, Perkin-Elmer, MA, USA) in transmission mode to make four scans in the 4000–680 cm−1 range at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 and a pixel size of 25 × 25 μm.

SEM and EDX mapping

SEM images and EDX maps were obtained at × 1000 magnification using a field emission scanning electron microscope (JSM-7800 F, JEOL, Japan) operating at an accelerating voltage of 7.0 kV at a 10-mm working distance. K-alpha is typically the strongest X-ray spectral line for an element bombarded with energy sufficient to cause maximally intense X-ray emission.

Western blot analysis

Protein concentration was quantified utilizing a commercial reagent (BCA; Pierce, IL, USA) and normalized to 0.5 or 1 μg μl−1 for all samples. A total of 10 μg of protein was applied to each lane of 15% polyacrylamide gels. The gel was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using Ezblot (AE-1460, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) reagent and a semi-dry blotting unit (WSE-4110 PoweredBLOT One, ATTO), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfer, the blots were blocked with a commercial blocking reagent (Can Get Signal PVDF Blocking Reagent; Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing in Tris-buffered saline (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl; pH 7.6) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), the blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in an immunoreaction-enhancer solution (Can Get Signal Solution 1; Toyobo). Primary antibodies used in this study were rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH (sc-25778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA; diluted 1:1000) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Pit-1 (sc-98814; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; diluted 1:1000). The membrane was washed in TBST and then reacted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (ab16284; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) diluted in an immunoreaction-enhancer solution (1:5000 in Can Get Signal Solution 2; Toyobo) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed again in TBST and processed using an enhanced chemiluminescence procedure (ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent; GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The ECL signals on the immunoblots were detected using a Fuji LAS1000-plus chemiluminescence imaging system (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.47; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.d. The data were primarily analyzed with Bartlett’s test for equality of variance. When homoscedasticity was not confirmed by Levene's test, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to the data. Based on the results of the Kruskal–Wallis tests, post hoc Steel-Dwass multiple comparisons were performed to compare the differences between various conditions. Data from the 2-APB investigation was analyzed by two-way ANOVA (magnesium supplementation × 2-APB). P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using JMP software (version 11.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Magnesium prevents phosphate-induced calcification in a rat aortic tissue culture

After the 10-day ex vivo incubation, the calcium content in aortas cultured in high-phosphate medium (3.8 mm l−1) was significantly increased compared with control, in agreement with previous investigations including our own.5, 6 When magnesium was added to the high-phosphate medium, VC (quantified as aortic calcium content) was suppressed in a dose-dependent manner, and almost completely prevented by supplementation with 2.0 mM magnesium (Figure 1).

Calcium content of aortic rings incubated under various conditions after 10 days of ex vivo incubation (n=8–10 rings obtained from eight rats). *Statistically significant compared with CON (P<0.05). #Statistically significant compared with HP (P<0.05). Ca, calcium; CON, control medium; HP, high-phosphate medium; Mg, magnesium; Pi, phosphorus.

FTIR imaging of phosphate distribution in aortic media

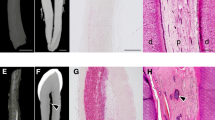

Figure 2 shows FTIR images of aortas cultured in various conditions for 10 days. In the FTIR images visualizing the distribution of phosphate ions at approximately 1035–1025 cm−1 (designated as hydroxyapatite), the white- and red-colored regions are areas of high infrared (IR) absorbance, whereas the blue region indicates weaker IR absorbance. Accordingly, the FTIR images show that phosphate accumulated in aortic rings cultured in several calcifying conditions (high phosphate, magnesium 1.2, and magnesium 1.6).

SEM images and EDX elemental maps of aortas cultured under various conditions. EDX elemental maps show phosphorus (Pi; red), calcium (Ca; green) and magnesium (Mg; blue). CON, control medium (0.9 mm Pi, 0.8 mm magnesium); EDX, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy; HP, high-phosphate medium (3.8 mM Pi, 0.8 mm magnesium); Mg 1.6, high-phosphate medium supplemented with 1.6 mm magnesium; Mg 2.0, high-phosphate medium supplemented with 2.0 mm magnesium; SEM, scanning electron microscopy. A full color version of this figure is available at the Hypertension Research journal online.

SEM–EDX imaging of phosphate, calcium and magnesium distribution in aortic media

As shown in Figure 3, both phosphate and calcium were barely present in aortic rings cultured in control medium, whereas they were markedly evident in the calcified areas of aortas cultured in high-phosphate conditions, consistent with our previous work.6 Magnesium distribution in aorta sections incubated with high phosphate was also compared with that in aorta cultured in control, and found to be reduced as magnesium concentration increased from 1.6 mM to 2.4 mM. The SEM–EDX overlay map demonstrated that phosphorus and calcium co-localized in the area of medial calcification induced by exposure to high-phosphate concentrations.

FTIR images of the distribution of phosphate (~1035–1025 cm−1, designated as hydroxyapatite) in aortas cultured under various conditions. CON, control medium (0.9 mm Pi, 0.8 mm magnesium); FTIR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; HP, high-phosphate medium (3.8 mm Pi, 0.8 mm magnesium); Mg, magnesium; Mg 1.6, high-phosphate medium supplemented with 1.6 mm Mg; Mg 2.0, high-phosphate medium supplemented with 2.0 mm Mg; P, phosphate; SEM, scanning electron microscopy. A full color version of this figure is available at the Hypertension Research journal online.

Inhibition of TRPM7 decreased the protective effect of magnesium on VC

The inhibitory effect of magnesium on phosphate-induced VC was partially decreased by 2-APB, an inhibitor of TRPM7 (Figure 4).

2-APB inhibits the effect of magnesium on VC (n=15–16 rings obtained from 10 rats). Two-way ANOVA (magnesium concentration × 2-ABP) was performed. Figure indicates the main effects of both magnesium concentration and 2-APB on VC in rat aorta. ANOVA, analysis of variance; 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxy-diphenylborate; Ca, calcium; HP, high-phosphate medium; Mg, magnesium; P, phosphate.

Magnesium inhibits the phosphate-induced increase in Pit-1 protein

Pit-1 protein in aortic rings maintained in high-phosphate medium for 10 days was significantly higher than that observed in control (~2.5-fold greater). After incubation in high-phosphate medium supplemented with 2.0 mm magnesium, Pit-1 was significantly decreased compared with that in sections cultured in high-phosphate conditions alone, in fact being comparable to levels in control samples instead (Figure 5).

Relative expression level of Pit-1 protein in aortic rings cultured for 10 days under various conditions. Values are Pit-1 protein expression normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) protein levels. * denotes statistically significant difference (P<0.05). CON, control medium; HP, high-phosphate medium, Mg, magnesium; P, phosphate.

Discussion

Previous clinical studies have suggested that lower serum magnesium levels are associated with increased VC,19, 20 and were supported by experimental studies demonstrating that magnesium directly prevents calcification in VSMCs.11, 16, 17, 18, 21 Because VSMCs lack the structure and matrix of a vessel, it is preferable to use an aortic tissue culture model to conduct in vitro investigation of the mechanism(s) involved in VC. Early indications were that magnesium attenuates the accumulation of calcium in the rat aortic tissue culture model, but these aortas were cultured without serum,11 which drastically accelerates calcification in VSMCs.22 We thus adopted the rat aortic tissue culture model using serum-supplemented medium—a more physiological condition—to evaluate the inhibitory effect of magnesium on VC. In the present study, we clearly demonstrate that magnesium prevents phosphate-induced VC in this rat tissue culture model (Figure 1), and replicate a previous finding from VSMC cultures11 that 2-APB—an inhibitor of TRPM7—negates this effect of magnesium (Figure 4).

Previous studies have also suggested that phosphate uptake through Pit-1—a member of the type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporter—is essential for calcification of VSMCs.5, 23, 24 Those studies, and our own previous investigation,6 demonstrated that Pit-1 is upregulated in high-phosphate conditions. In the present study, we verified that Pit-1 protein expression was increased by high-phosphate conditions, a phenomenon that was reversed by supplementation with a high magnesium concentration. It is unclear why or how magnesium regulates the expression of Pit-1 protein; we aim to elucidate this in subsequent investigations.

Calcium deposits in aortic sections can be visualized using the von Kossa method, which stains both soluble (chlorides and sulphates) and insoluble (carbonates and phosphates) calcium compounds.5, 25, 26 Because this method is unable to quantify the type of calcium salt, we went further in our previous report by revealing the distributions of calcium and phosphate in structural medial calcifications using FTIR and SEM–EDX.6 These techniques can visualize distributions of both individual mineral elements and specific calcium compounds such as phosphate (1035–1025 cm−1) that are indicative of hydroxyapatite in aortic rings. All elements (phosphate, calcium and magnesium) accumulated in calcified sections under high-phosphate conditions but this accumulation was gradually diminished by increasing magnesium concentrations. These data suggest that the inhibitory effect of magnesium on VC is unlikely to be caused by either replacement of magnesium with calcium, or by excessive magnesium accumulation.

In vitro studies of VC have mostly used cell culture systems, but because these models lack the structure and matrix of a normal vessel, the extrapolation of these findings to more physiological scenarios is of limited value. The aortic tissue culture model used in the present study is more physiologically relevant, and indicated that magnesium prevents high-phosphate-induced VC via actions on TRPM7 and Pit-1. In further investigation, we aim to clarify the mechanistic basis of how magnesium regulates Pit-1.

We previously reported that hypermagnesemia, defined as serum Mg level ⩾2.2 mg dl−1 (0.92 mm), was found in 53.9% of uremic patients and develops frequently in those with an eGFR <5 ml min−1.12 The present study suggests that 2.0 mm magnesium almost completely prevents VC in an aortic tissue culture model. Higher serum magnesium might be beneficial for patients presenting vascular calcification such as in CKD. Several clinical symptoms develop at serum magnesium levels above 2.5 mm and severe disorders are observed at levels greater than 5mmol l−1.27 Further study and interventions are needed for CKD patients.

References

Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM . Arterial calcification, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2001; 38: 938–942.

London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Métivier F, Pannier B, Adda H . Arterial media calcification in end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18: 1731–1740.

Ohya M, Otani H, Kimura K, Saika Y, Fujii R, Yukawa S, Shigematsu T . Vascular calcification estimated by aortic calcification area index is significant predictive parameter of cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin Exp Nephrol 2011; 15: 877–883.

László A, Reusz G, Nemcsik J . Ambulatory arterial stiffness in chronic kidney disease: a methodological review. Hypertens Res 2016; 39: 192–198.

Mune S, Shibata M, Hatamura I, Saji F, Okada T, Maeda Y, Sakaguchi T, Negi S, Shigematsu T . Mechanism of phosphate-induced calcification in rat aortic tissue culture: possible involvement of Pit-1 and apoptosis. Clin Exp Nephrol 2009; 13: 571–577.

Sonou T, Ohya M, Yashiro M, Masumoto A, Nakashima Y, Ito T, Mima T, Negi S, Kimura-Suda H, Shigematsu T . Mineral composition of phosphate-induced calcification in a rat aortic tissue culture model. J Atheroscler Thromb 2015; 22: 1197–1206.

Adamopoulos C, Pitt B, Sui X, Love TE, Zannad F, Ahmed A . Low serum magnesium and cardiovascular mortality in chronic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Int J Cardiol 2009; 136: 270–277.

Ishimura E, Okuno S, Yamakawa T, Inaba M, Nishizawa Y . Serum magnesium concentration is a significant predictor of mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Magnes Res 2007; 20: 237–244.

Sakaguchi Y, Fujii N, Shoji T, Hayashi T, Rakugi H, Isaka Y . Hypomagnesemia is a significant predictor of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Kidney Int 2013; 85: 174–181.

Yamori Y, Sagara M, Mizushima S, Liu L, Ikeda K, Nara Y, CARDIAC Study Group. An inverse association between magnesium in 24-h urine and cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged subjects in 50 CARDIAC Study populations. Hypertens Res 2015; 38: 219–225.

Salem S, Bruck H, Bahlmann FH, Peter M, Passlick-Deetjen J, Kretschmer A, Steppan S, Volsek M, Kribben A, Nierhaus M, Jankowski V, Zidek W, Jankowski J . Relationship between magnesium and clinical biomarkers on inhibition of vascular calcification. Am J Nephrol 2012; 35: 31–39.

Kanbay M, Yilmaz MI, Apetrii M, Saglam M, Yaman H, Unal HU, Gok M, Caglar K, Oguz Y, Yenicesu M, Cetinkaya H, Eyileten T, Acikel C, Vural A, Covic A . Relationship between serum magnesium levels and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Nephrol 2012; 36: 228–237.

Ohya M, Negi S, Sakaguchi T, Koiwa F, Ando R, Komatsu Y, Shinoda T, Inaguma D, Joki N, Yamaka T, Ikeda M, Shigematsu T . Significance of serum magnesium as an independent correlative factor on the parathyroid hormone level in uremic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 3873–3878.

Gorgels TG, Waarsing JH, de Wolf A, ten Brink JB, Loves WJ, Bergen AA . Dietary magnesium, not calcium, prevents vascular calcification in a mouse model for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Mol Med 2010; 88: 467–475.

De Schutter TM, Behets GJ, Geryl H, Peter ME, Steppan S, Gundlach K, Passlick-Deetjen J, D'Haese PC, Neven E . Effect of a magnesium-based phosphate binder on medial calcification in a rat model of uremia. Kidney Int 2013; 83: 1109–1117.

Bai Y, Zhang J, Xu J, Cui L, Zhang H, Zhang S, Feng X . Magnesium prevents β-glycerophosphate-induced calcification in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. Biomed Rep 2015; 3: 593–597.

Kircelli F, Peter ME, Sevinc Ok E, Celenk FG, Yilmaz M, Steppan S, Asci G, Ok E, Passlick-Deetjen J . Magnesium reduces calcification in bovine vascular smooth muscle cells in a dose-dependent manner. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 514–521.

Louvet L, Büchel J, Steppan S, Passlick-Deetjen J, Massy ZA . Magnesium prevents phosphate-induced calcification in human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28: 869–878.

Meema HE, Oreopoulos DG, Rapaport A . Serum magnesium level and calcification in end–stage renal disease. Kidney Int 1987; 32: 388–394.

Tzanakis I, Pras A, Kounali D, Mamali V, Kartsonakis V, Mayopoulou-Symvoulidou D, Kallivretakis N . Mitral annular calcifications in haemodialysis patients: a possible protective role of magnesium. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997; 12: 2036–2037.

Montezano AC, Zimmerman D, Yusuf H, Burger D, Chignalia AZ, Wadhera V, van Leeuwen FN, Touyz RM . Vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation to an osteogenic phenotype involves TRPM7 modulation by magnesium. Hypertension 2010; 56: 453–462.

Reynolds JL, Joannides AJ, Skepper JN, McNair R, Schurgers LJ, Proudfoot D, Jahnen-Dechent W, Weissberg PL, Shanahan CM . Human vascular smooth muscle cells undergo vesicle-mediated calcification in response to changes in extracellular calcium and phosphate concentration: a potential mechanism for accelerated vascular calcification in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 2857–2867.

Mikroulis D, Mavrilas D, Kapolos J, Koutsoukos PG, Lolas C . Physicochemical and microscopical study of calcific deposits from natural and bioprosthetic heart valves. Comparison and implications for mineralization mechanism. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2002; 13: 885–889.

Becker A, Epple K, Muller KM, Schmitz I . A comparative study of clinically well-characterized human atherosclerotic plaques with histological, chemical, and ultrastructural methods. J Inorg Biochem 2004; 98: 2032–2038.

Lomashvili KA, Cobbs S, Hennigar RA, Hardcastle KI, O'Neill WC . Phosphate-induced vascular calcification: role of pyrophosphate and osteopontin. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 1392–1401.

Lomashvili KA, Garg P, O’Neill WC . Chemical and hormonal determinants of vascular calcification. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 1464–1470.

Touyz RM . Magnesium in clinical medicine. Front Biosci 2004; 9: pp1278–1293.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 25461251), and a grant for pathophysiological research in chronic kidney disease from The Kidney Foundation, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sonou, T., Ohya, M., Yashiro, M. et al. Magnesium prevents phosphate-induced vascular calcification via TRPM7 and Pit-1 in an aortic tissue culture model. Hypertens Res 40, 562–567 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.188

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2016.188

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between serum magnesium levels and cognitive function in patients undergoing hemodialysis

Clinical and Experimental Nephrology (2024)

-

Vascular calcification in different arterial beds in ex vivo ring culture and in vivo rat model

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Deposition of calcium in an in vitro model of human breast tumour calcification reveals functional role for ALP activity, altered expression of osteogenic genes and dysregulation of the TRPM7 ion channel

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Cardiovascular disease, mortality, and magnesium in chronic kidney disease: growing interest in magnesium-related interventions

Renal Replacement Therapy (2018)