Abstract

Objective:

To validate the use of waist circumference to assess reversal of insulin resistance after weight loss induced by bariatric surgery.

Design:

In cross-sectional studies, threshold values for insulin resistance were determined with homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (algorithm based on fasting plasma glucose and insulin) in 1018 lean subjects and by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (clamp) in 26 lean women. In a cohort study on 211 patients scheduled for bariatric surgery, HOMA-IR and waist circumference were measured before and 1.5–3 years after weight reduction. In a subgroup of 53 women, insulin sensitivity was also measured using clamp.

Results:

The threshold for insulin resistance (90th percentile) was 2.21 (mg dl−1 fasting glucose × mU l−1 fasting insulin divided by 405) for HOMA-IR and 6.118 (mg glucose per kg body weight per minute) for clamp. Two methods to assess reversal of insulin resistance by measuring waist circumference were used. A single cutoff value to <100 cm for waist circumference was associated with reversal of insulin resistance with an odds ratio (OR) of 49; 95% confidence interval (CI)=7–373 and P=0.0002. Also, a diagram based on initial and weight loss-induced changes in waist circumference in patients turning insulin sensitive predicted reversal of insulin resistance following bariatric surgery with a very high OR (32; 95% CI=4–245; P=0.0008). Results with the clamp cohort were similar as with HOMA-IR analyses.

Conclusions:

Reversal of insulin resistance could either be assessed by a diagram based on initial waist circumference and reduction of waist circumference, or by using 100 cm as a single cutoff for waist circumference after weight reduction induced by bariatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For many years, the prevalence of obesity has increased in an epidemic fashion in most regions of the world. This will cause a major health economic burden owing to a predicted rise in obesity-related complications.1, 2 Insulin resistance is common among the obese and a major pathogenic factor behind obesity-associated type 2 diabetes; however, it is reversible by weight reduction.3, 4 Despite its medical relevance, insulin sensitivity is rarely assessed in clinical practise. There is an unmet need among clinicians as well as patients for a simple clinical tool for assessment of presence and reversal of insulin resistance among obese. Clinicians as well as the obese patients could use such a tool.

Waist circumference might serve the purpose mentioned above. It is a valid, reliable and easy-to-use method5 that is strongly associated with type 2 diabetes6 and also a strong predictor of type 2 diabetes.7, 8, 9 Waist circumference has also been shown to predict the presence of insulin resistance with high precision in cross-sectional examinations.10 In this respect, it is superior to other common measures of body shape such as waist-to-hip ratio, body fat content and body mass index (BMI).10 Unlike gender-specific cutoff values for waist circumference, which often are used to predict other obesity complications, a value <100 cm excludes the presence of insulin resistance with >90% sensitivity and >60% specificity in either sex.10 On the other hand, the usefulness of waist circumference to assess reversal of insulin resistance following weight reduction is unknown.

Bariatric surgery is an effective method to achieve weight loss that is sustainable over time and has been shown to reduce mortality and cardiovascular events as recently reviewed in detail.11 Surgical treatment of obesity has also been shown to increase the remission rate of type 2 diabetes to prevent development of type 2 diabetes.12 However, in many patients treated with bariatric surgery, there is a relapse of diabetes over time and prevention of the disease following weight loss is not complete.11, 12 In theory, these treatment failures could at least be partly owing to the maintenance of an insulin-resistant state after bariatric surgery.

In this study, we have investigated whether waist circumference can be used to assess reversal of insulin sensitivity following weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. For this purpose, we measured insulin sensitivity and waist circumference in obese subjects before and after gastric bypass or gastric banding operations. Insulin sensitivity was assessed with either homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) or with hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (clamp).

Materials and methods

Cohort study one validating waist circumference to predict reversal of insulin resistance measured by HOMA-IR after weight loss

Obese patients who were scheduled for bariatric surgery in the Stockholm region in Sweden were examined in the morning after an overnight fast before surgery. Weight was measured to the nearest complete 0.5 kg with a digital scale (TANITA model no TBF-305). Waist circumference (measured at the midpoint between the lateral lower rib and iliac crest with a non-stretchable tape measure) and height (measured by a fixed tape measure at a wall) were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Anthropometric measurements were performed by research nurses with appropriate training. BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height. A venous blood sample was taken and plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method. Plasma insulin was determined using an ELISA kit (Insulin ELISA, Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). The two patients who were treated with insulin for type 2 diabetes were instructed not to take insulin the night before or in the morning before the blood samples were collected. Insulin sensitivity was determined by HOMA-IR that was calculated using the formula HOMA-IR=fasting plasma glucose (mg dl−1) × fasting plasma insulin (mU l−1)/405 as previously described.13

Postoperatively, patients undergoing gastric bypass were prescribed supplementation with vitamin B12, calcium, vitamin D3 and iron (menstruating women only) in addition to multivitamin, including folic acid and vitamin B12, whereas those operated with adjustable gastric banding were prescribed multivitamin supplementation only. Patients were seen 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after surgery and instructed to check their weight themselves every third month. On 40 patients, it was possible to obtain fasting plasma insulin and glucose values in addition to anthropometric measurements. The patients were considered weight stable either when they themselves reported weight stability over 3 months or when they had the same weight at two consecutive visits. When body weight was reduced to this steady-state level, 1.5–3 years after surgery, the patients were re-examined for waist circumference and insulin sensitivity.

Cohort study two validating waist circumference to predict reversal of insulin resistance measured by clamp after weight loss

To validate the use of waist circumference as a marker for reversal of insulin resistance, we investigated whether it also correlated with a direct measure of insulin resistance measured by the use of clamp. Fifty-three women from cohort study one also underwent a clamp procedure in the morning after an overnight fast (that is, 25% of the patients in cohort study one). The clamp procedure has been described in detail previously.14 In brief, an intravenous bolus dose of insulin (1.6 U m−2 body surface area; Actrapid, Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) was given followed by a continuous intravenous infusion of insulin (0.12 U m−2 × min) for 120 min. Blood glucose was measured in duplicates every fifth minute (Hemocue, Ängelholm, Sweden) and euglycemia (81–99 mg dl−1) was maintained through a variable intravenous infusion of glucose (200 mg ml−1). Measurements during the last 60 minutes were used for calculation of whole-body glucose disposal rate (mg glucose per kg body weight per minute, M-value).

Cross-sectional studies used to establish threshold for insulin resistance

We retrospectively analysed collected data from a sample of 3278 subjects (2324 women and 954 men), who had been recruited from the Stockholm (Sweden) area to our unit in order to study genetic factors influencing body weight.15 They were investigated once exactly as described for cohort one in the determination of HOMA-IR. In addition, 26 lean and healthy women were recruited to establish a cutoff value for insulin sensitivity measured by clamp. They were investigated once as described for cohort two.

Statistical analyses

Values are mean±s.d. Unpaired t-test was used to compare the subgroup that underwent clamp procedure with the rest of cohort one. Linear regression analysis and analysis of covariance were used to compare initial waist circumference with values for reduction of waist circumference after surgery. For obese insulin-resistant patients who were investigated before and after bariatric surgery, odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from a publicly available calculator (www.medcalc.org/calc/odds.ratio). The following statistical programs were used: Statistica 10 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) and Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Cross-sectional studies

Of the 3278 subjects in the cross-sectional study, we used data from the 1018 lean subjects (735 women and 283 men with a BMI <25 kgm−2) to determine a threshold for insulin resistance that was not influenced by excess body fat levels. The clinical characteristics of the 1018 subjects are described in Table 1. Insulin resistance was defined as values above the 90th percentile of HOMA-IR value of these lean subjects that was 2.21 mg dl−1 × mU l−1 (2.27 mg dl−1 × mU l−1 for men and 2.17 mg dl−1 × mU l−1 for women). The clinical characteristics of the 26 lean women used to define insulin resistance by clamp are described in Table 1. The cutoff value for insulin resistance measured by clamp was defined as the lower 90th percentile and was 6.118 mg glucose per kg body weight per minute.

Cohort study one (HOMA-IR)

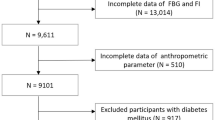

Initially, 266 patients were included in the study cohort. Thirty-one patients did not come to the second research examination in spite of several reminders. An additional 24 patients were excluded from the final analysis as data were missing. In total, 211 patients (44 men and 167 women) were included (Figure 1). Forty-two were operated with adjustable gastric banding and 169 with gastric bypass. Thirty-five were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes before operation and 80% (n=167) were insulin resistant preoperatively according to the cutoff value for HOMA-IR. Two diabetic patients were treated with insulin and the remaining ones with diet or diet plus metformin. The clinical characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 2.

At the time of the second examination when body weight had decreased to a new steady-state level, the patients had reduced their BMI, waist circumference and HOMA-IR by on average 13.1±5.0 kg m−2, 32.2 ±12.4 cm and 3.4 ±3.3 mg dl−1 × mU l−1, respectively. Forty-four patients who were insulin sensitive before operation remained insulin sensitive at the follow-up visit. These 44 patients were excluded from further analysis, which focused on those being insulin resistant before surgery (n=167).

We compared the reduction in waist circumference after weight loss with the initial waist circumference. There was a strong linear correlation between the two parameters (r=0.43; P<0.0001). We subsequently divided the data set based on turning insulin sensitive or remaining insulin resistant after the weight reduction (Figure 2a). The two values correlated strongly in both groups and the regression lines differed by analysis of covariance (F=72; P<0.0001). The regression line that represents patients turning insulin sensitive has the following equation: predicted reduction in waist circumference=0.35 times initial value minus 11.22. We subsequently made a diagram using the above-mentioned regression line and analysed the distribution of subjects based on if they turned insulin sensitive or remained insulin resistant and if they were above (74 turning insulin sensitive and 1 remaining insulin resistant) or below (64 turning insulin sensitive and 28 remaining insulin resistant) the regression line. By using the diagram, it was possible to predict with very high probability if the obese patients turned sensitive after weight loss by comparing the actual reduction in waist circumference with the starting value. OR for turning sensitive was 32 (95% CI=4–245, P=0.0008) for values of waist circumference above the line. Based on data from a previous cross-sectional study,10 we wanted to investigate if a second method, using 100 cm as a threshold value for waist circumference, also could be used to assess reversal of insulin resistance after weight reduction. Of the 167 patients that were insulin resistant before surgery, 89 reached a waist circumference below 100 cm and those were very likely to have reversed their insulin resistance as opposed to the patients who still had a waist circumference ⩾100 cm (n=78) (Figure 2b). OR for turning insulin sensitive was 49 (P=0.0002).

Assessment of reversal of insulin resistance after bariatric surgery using HOMA-IR cutoff ⩾2.21 mg dl−1 × mU l−1; in the whole cohort (a) and (c) (n=167), in a separate analysis of the women (b) (n=125) and using clamp cutoff ⩽6.118 mg glucose per kg body weight per minute (d) and (e) (n=49). (a, c and d) Comparison of initial waist circumference with waist circumference reduction and reversal or maintenance of insulin resistance. Included patients were insulin resistant before weight reduction. Filled dots and broken line represent patients remaining resistant whereas open circles and solid line represent patients turning sensitive. (b and e) Assessment of the use of <100 cm as cutoff value for waist circumference after weight reduction to assess reversal of insulin resistance.

The results from the equation method to assess reversal of insulin resistance presented in Figure 2a were compared with the results from the single cutoff method in Figure 2b. The single cutoff value for waist circumference (100 cm) was most useful at initial waist circumference <135 cm. If instead the diagram method was used for these patients, they had to reduce their waist circumference to much lower values than 100 cm in order to reverse the risk. However, if the diagram is used on patients with initial values >135 cm, waist circumference can be reduced to higher values than 100 cm and still predict reversal of insulin resistance. The following examples are given. In order to predict reversal of insulin resistance on a patient with a waist circumference of 120 cm before weight reduction, the patient needs to reduce the waist circumference to 90 cm according to the diagram instead of just below the cutoff value of 100 cm, which would be sufficient according to Figure 2b. On the other hand, a patient with an initial waist circumference of 150 cm only needs to reach below 110 cm according to the diagram instead of <100 cm according to Figure 2a in order to exclude insulin resistance.

This study included men and women. The women (n=125) who were initially insulin resistant were investigated separately with the diagram method mentioned above. The outcome was essentially the same as for the whole cohort. The results with those turning sensitive differed markedly from those remaining insulin resistant (F=50; P<0.0001). The formula for the regression line of women turning insulin sensitive in Figure 2c is predicted reduction in waist circumference (cm)=0.374 times initial waist circumference minus 13.21. When assessing the use of this regression line in the same way as mentioned above, all 89 above the regression line became insulin sensitive and 20 out of 36 became insulin sensitive below the line. OR for turning insulin sensitive using this diagram was 144 (95% CI=8–2501; P=0.00086).

Patients in cohort one were also subdivided into mode of surgery. There were no apparent differences in outcome in patients treated with gastric bypass or gastric banding.

Cohort study two (clamp)

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort, which is a subpopulation of cohort 1, are found in Table 2. Age, BMI and waist circumference of this cohort were not significantly different from the remaining patients in cohort one as examined by unpaired t-test (values not shown). As in cohort one, we excluded the obese patients being insulin sensitive before surgery and focused on those who were insulin resistant at start (n=49). A positive correlation between initial values for waist circumference and the reduction of waist circumference after bariatric surgery was observed. The regression line for patients turning insulin sensitive (n=33) differed significantly from the regression line for patients remaining insulin resistant (n=16) after surgery (F=9.3; P=0.004 in Figure 2d). The equation for the solid line representing those turning sensitive was as follows: predicted reduction in waist circumference =0.751 times initial value minus 60.35. It was used to construct a similar diagram as for cohort one. Above the line, 18 turned insulin sensitive and 2 remained insulin resistant, whereas 15 turned insulin sensitive and 14 remained insulin resistant below the line. It was possible to assess the likelihood to turn sensitive after weight loss with high probability also using this diagram. OR for turning insulin sensitive for values of waist circumference being above the line is 8.4 (95% CI =1.6–43.0; P=0.01).

The second method to assess reversal of insulin resistance with a single cutoff value of <100 cm for waist circumference was also investigated (Figure 2e). Thirty-one patients reduced their waist circumference to <100 cm after bariatric surgery whereas 18 patients still had a higher value. The likelihood of becoming insulin sensitive was high when waist circumference was reduced below the 100 cm cutoff value (OR=4.2; P=0.02).

Studies of a subgroup from cohort one

On 40 patients in cohort one, we had information about waist circumference plus fasting plasma insulin and glucose values during the intermediate check-ups before the final examinations. It is demonstrated in Figure 3 that dynamic changes in waist circumference and reversal of insulin resistance was almost superimposed. There was a steep improvement of both factors during the first 6 months and this improvement continued but at a more moderate degree until final examination.

Discussion

This study shows that waist circumference can be used to assess reversal of insulin resistance in obese patients following weight loss after bariatric surgery. This suggests that waist circumference measure is a valuable tool to indirectly evaluate the remaining risk of developing type 2 diabetes or having a relapse of the disease after surgically induced weight reduction. Two methods can be used. The diagram/equation method is most useful in the markedly obese with a very large initial waist circumference whereas the single cutoff method is more favourable for obese with smaller initial waist circumference. In the former obese group, the target value of waist circumference after weight loss that is associated with low risk of remaining insulin resistant is >100 cm. In the latter group this target is <100 cm. The critical value using either method is an initial waist circumference of 135 cm when HOMA-IR is used to assess insulin sensitivity.

Waist circumference has as far as we know not been used previously to investigate reversal of insulin resistance. However, baseline values have been studied frequently to assess risk of obesity complications. Several studies report a very high precision of both intra- and inter-operative measurements and of self-measurements5, 16, 17, 18, 19 Waist circumference seems less valuable to detect cardiovascular risk20, 21 than to estimate the risk of developing type 2 diabetes6, 7, 8, 9 or sudden death.22 Different cutoff values for waist circumference in men and women are usually used to estimate health-related risks. The most frequently used cutoff values (102 cm for men and 88 cm for women) derive from a study where waist circumference was used as a measure for indicating need for weight management.23 However, for insulin resistance, as measured by HOMA-IR, a single measure (100 cm) can be used in either sex for cutoff value.10

Other anthropometric measures have also been used to estimate insulin sensitivity. Sagittal abdominal diameter is an even stronger indirect measure than waist circumference of insulin resistance.24 However, it requires a specific device and is therefore less suitable for clinical practice and cannot be used for self-measurements. In the lean subjects, we obtained almost identical average values for insulin sensitivity between men and women using HOMA-IR. In studies also including overweight and obese subjects, the women are usually more insulin sensitive than men as reviewed.25 Thus, a difference in insulin sensitivity between men and women may above all to be found in overweight or obese subjects.

The major strength with this study is that it identifies simple methods to assess reversal of insulin resistance in obese patients following weight reduction. The use of waist circumference appears to be useful after gastric bypass as well as gastric banding operations. However, it should be acknowledged that a direct comparison of the surgical methods is not possible in this study. First, the surgical method was not randomized. Second, the number of patients undergoing gastric banding was too low to be compared with those operated with gastric bypass.

The data from the current study suggest that either a diagram/equation based on initial and reduced value for waist circumference or a single cutoff value for reduced waist circumference regardless of initial waist circumference can be used. The former method seems to be most accurate for patients with a very large waist circumference (>135 cm) as they do not need to reach 100 cm in order to reverse their insulin resistance. On the other hand, in obese patients with a smaller initial waist circumference (<135 cm before weight loss), the threshold 100 cm for waist circumference can be used as goal instead of a value based on the equation/diagram because the latter value is much lower than 100 cm and, thus, hard to achieve.

When should reversal of insulin resistance following bariatric surgery be measured? Our subgroup analyses suggest that already 6 months after surgery most of the beneficial effect is observed. However, there is additional value to wait until body weight is further reduced to steady-state level. In our cohort, 44 subjects (21%) were obese and insulin sensitive before operation. This is in good agreement with the observation that about 30% of obese subjects might be classified as healthy obese as discussed in a well written review by Blüher.26 These individuals might benefit less from weight loss induced by bariatric surgery26 and they were not included in the final analysis as we wanted to study reversal of insulin resistance. It should be stressed that we only investigated marked long-term weight loss induced by bariatric surgery. It remains to be established if waist circumference measures also are valuable to assess the effect of weight reduction with alternative methods such as diet and exercise. On the other hand, such alternative methods are much less efficient as regards long-term effects on weight reduction compared with bariatric surgery.

Predictive cutoff values for waist circumference and insulin resistance may differ between ethnic groups. In this study, Caucasian subjects were investigated. There is a possibility that there are other, and maybe gender specific, optimal cutoff values in other populations.

A limitation of the present study is that HOMA-IR index is only an indirect estimation of insulin resistance. However, it shows a strong correlation with the ‘gold standard’ clamp method both in non-diabetics and type 2 diabetics as reviewed.13 Furthermore, we validated our results by performing hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps in a subgroup of obese subjects. These results of direct measurements of insulin resistance were in good agreement with the HOMA-IR results as regards the prediction of reversal of insulin resistance following weight reduction. This study includes more women than men; the reason being that women are more prone to seek medical care for obesity than men. In Sweden, about 70% of bariatric surgical procedures are performed on women.

In conclusion, reversal of insulin resistance following weight loss after bariatric surgery can be predicted with high accuracy by measuring waist circumference. Different methods can be used dependent on how large waist circumference is before weight reduction. These results should encourage clinicians to include the simple, inexpensive and rapid tape measurement of waist circumference. The tool is also suitable for self-measurements by the patients. It may also be useful in prospective epidemiological studies of relapse and prevention of type 2 diabetes following bariatric surgery where direct measure of insulin sensitivity is not available.

References

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011; 378: 804–814.

Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M . Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011; 378: 815–825.

Reaven GM . Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am 2011; 95: 875–892.

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ . The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005; 365: 1415–1428.

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC . Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology 1990; 1: 466–473.

Balkau B, Deanfield JE, Despres JP, Bassand JP, Fox KA, Smith SC Jr. et al. International Day for the Evaluation of Abdominal Obesity (IDEA): a study of waist circumference, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus in 168,000 primary care patients in 63 countries. Circulation 2007; 116: 1942–1951.

Wang Y, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB . Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81: 555–563.

Janiszewski PM, Janssen I, Ross R . Does waist circumference predict diabetes and cardiovascular disease beyond commonly evaluated cardiometabolic risk factors? Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 3105–3109.

Wannamethee SG, Papacosta O, Whincup PH, Carson C, Thomas MC, Lawlor DA et al. Assessing prediction of diabetes in older adults using different adiposity measures: a 7 year prospective study in 6,923 older men and women. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 890–898.

Wahrenberg H, Hertel K, Leijonhufvud BM, Persson LG, Toft E, Arner P . Use of waist circumference to predict insulin resistance: retrospective study. BMJ 2005; 330: 1363–1364.

Sjostrom L . Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial: a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2012; 273: 219–234.

Carlsson LM, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Anveden A, Bouchard C, Carlsson B et al. Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 695–704.

Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR . Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1487–1495.

Hagstrom-Toft E, Thorne A, Reynisdottir S, Moberg E, Rossner S, Bolinder J et al. Evidence for a major role of skeletal muscle lipolysis in the regulation of lipid oxidation during caloric restriction in vivo. Diabetes 2001; 50: 1604–1611.

Jiao H, Arner P, Hoffstedt J, Brodin D, Dubern B, Czernichow S et al. Genome wide association study identifies KCNMA1 contributing to human obesity. BMC Med Genomics 2011; 4: 51.

Mueller WH, Malina RM . Relative reliability of circumferences and skinfolds as measures of body fat distribution. Am J Phys Anthropol 1987; 72: 437–439.

Ferrario M, Carpenter MA, Chambless LE . Reliability of body fat distribution measurements. The ARIC Study baseline cohort results. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995; 19: 449–457.

Chen MM, Lear SA, Gao M, Frohlich JJ, Birmingham CL . Intraobserver and interobserver reliability of waist circumference and the waist-to-hip ratio. Obes Res 2001; 9: 651.

Weaver TW, Kushi LH, McGovern PG, Potter JD, Rich SS, King RA et al. Validation study of self-reported measures of fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1996; 20: 644–650.

Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from shaping America's health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1647–1652.

Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Wood AM, Pennells L, Thompson A et al. Separate and combined associations of body-mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet 2011; 377: 1085–1095.

Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 2105–2120.

Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE . Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ 1995; 311: 158–161.

Riserus U, Arnlov J, Brismar K, Zethelius B, Berglund L, Vessby B . Sagittal abdominal diameter is a strong anthropometric marker of insulin resistance and hyperproinsulinemia in obese men. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2041–2046.

Geer EB, Shen W . Gender differences in insulin resistance, body composition, and energy balance. Gender Med 2009; 6 (Suppl 1): 60–75.

Bluher M . Are there still healthy obese patients? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2012; 19: 341–346.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Swedish Research Council, Stockholm County Council, Swedish Diabetes Association, Novo Nordic Foundation, Strategic Research Programme in Diabetes at Karolinska Institutet and the Erling–Persson Family Foundation. The skilful assistance of Kerstin Wåhlén and Eva Sjölin is greatly acknowledged. This study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm, Sweden, number 2010/1046-32, 208/1010-31/3, 2009/163-32 and 2010/1301-32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, D., Wahrenberg, H., Toft, E. et al. Waist circumference to assess reversal of insulin resistance following weight reduction after bariatric surgery: cohort and cross-sectional studies. Int J Obes 38, 438–443 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.88

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.88

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Metabolic shift precedes the resolution of inflammation in a cohort of patients undergoing bariatric and metabolic surgery

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Reduced Th1 response is associated with lower glycolytic activity in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells after metabolic and bariatric surgery

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2021)

-

Waist circumference-dependent peripheral monocytes change after gliclazide treatment for Chinese type 2 diabetic patients

Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology [Medical Sciences] (2017)

-

Adipose tissue morphology predicts improved insulin sensitivity following moderate or pronounced weight loss

International Journal of Obesity (2015)

-

Osteocalcin increase after bariatric surgery predicts androgen recovery in hypogonadal obese males

International Journal of Obesity (2014)